How Dietary Choices and Nutritional Knowledge Relate to Eating Disorders and Body Esteem of Medical Students? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

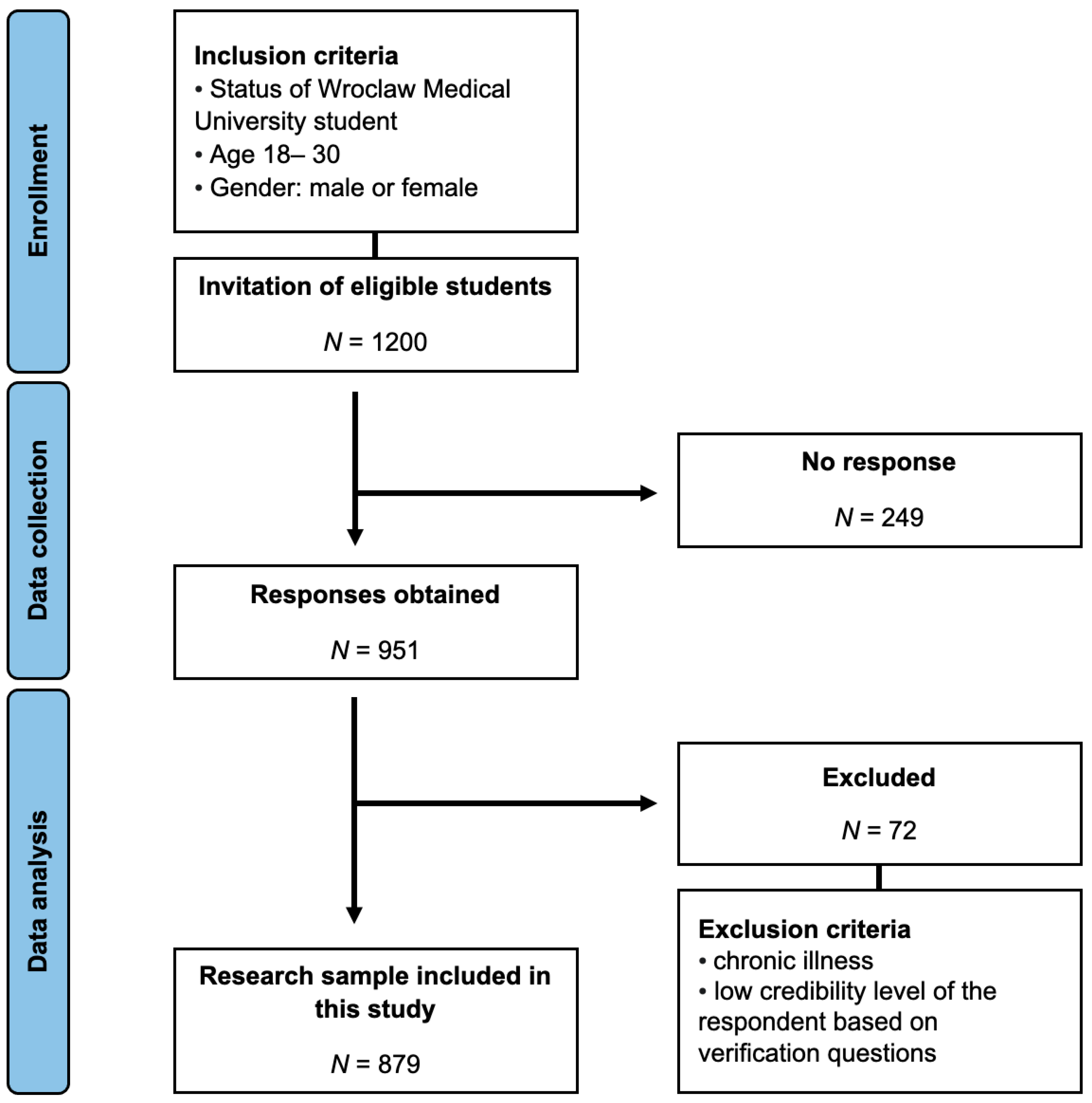

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. KomPAN

2.3. Body Esteem Scale (BES)

2.4. The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weiselberg, E.C.; Gonzalez, M.; Fisher, M. Eating Disorders in the Twenty-First Century. Minerva Ginecol. 2011, 63, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Melioli, T. The Relationship Between Body Image Concerns, Eating Disorders and Internet Use, Part I: A Review of Empirical Support. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhas, L.; Morris, A.; Crosby, R.D.; Katzman, D.K. Incidence and Age-Specific Presentation of Restrictive Eating Disorders in Children: A Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program Study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benowitz-Fredericks, C.A.; Garcia, K.; Massey, M.; Vasagar, B.; Borzekowski, D.L.G. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and the Relationship to Adolescent Media Use. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 59, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovski, N.; Jaeger, T. Demystifying ‘Diet Culture’: Exploring the Meaning of Diet Culture in Online ‘Anti-Diet’ Feminist, Fat Activist, and Health Professional Communities. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2022, 90, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.C.; White, E.K.; Srinivasan, V.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationships between Body Checking, Body Image Avoidance, Body Image Dissatisfaction, Mood, and Disordered Eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiuza, A.; Rodgers, R.F. The Effects of Brief Diet and Anti-Diet Social Media Videos on Body Image and Eating Concerns among Young Women. Eat. Behav. 2023, 51, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M. Effect of Family Pressure, Peer Pressure, and Media Pressure on Body Image Dissatisfaction among Women. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 8, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, I.; Sharma, S.; Khosla, M. Social Anxiety Disorder Among Adolescents in Relation to Peer Pressure and Family Environment. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Commun. 2020, 13, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.C.; Fraser, K.; Rumana, N.; Abdullah, A.F.; Shahana, N.; Hanly, P.J.; Turin, T.C. Sleep Disturbances among Medical Students: A Global Perspective. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Hasan, S.; Malik, S.; Sreeramareddy, C.T. Perceived Stress, Sources and Severity of Stress among Medical Undergraduates in a Pakistani Medical School. BMC Med. Educ. 2010, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wege, N.; Muth, T.; Li, J.; Angerer, P. Mental Health among Currently Enrolled Medical Students in Germany. Public Health 2016, 132, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlin, M.E.; Runeson, B. Burnout and Psychiatric Morbidity among Medical Students Entering Clinical Training: A Three Year Prospective Questionnaire and Interview-Based Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2007, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enns, M.W.; Cox, B.J.; Sareen, J.; Freeman, P. Adaptive and Maladaptive Perfectionism in Medical Students: A Longitudinal Investigation. Med. Educ. 2001, 35, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Asadi, J. Perceived stress and eating habits among medical students. Int. J. Med. Pharm. Sci. (IJMPS) 2014, 4, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Din, Z.; Iqbal, K.; Khan, I.; Abbas, M.; Ghaffar, F.; Iqbal, Z.; Iqbal, M.; Ilyas, M.; Suleman, M.; Iqbal, H. Tendency Towards Eating Disorders and Associated Sex-Specific Risk Factors Among University Students. Noro Psikiyatr. Ars. 2019, 56, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Faris, M.A.-I.; AlAnsari, A.M.S.; Taha, M.; AlAnsari, N. Prevalence of Sleep Problems among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.R.; Loeb, K.L.; McGlinchey, E.L. Sleep and Eating Disorders: Current Research and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 34, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; Sater, M.; Abdulla, A.; Faris, M.A.-I.; AlAnsari, A. Eating Disorders Risk among Medical Students: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2019, 24, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An Update on the Prevalence of Eating Disorders in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, J.M.O.; Ramos-Cerqueira, A.T.A.; Lima, M.C.P.; Torres, A.R. Social Anxiety Symptoms and Body Image Dissatisfaction in Medical Students: Prevalence and Correlates. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2018, 67, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sugimoto, S.; Recker, D.; Halvorson, E.E.; Skelton, J.A. Are Future Doctors Prepared to Address Patients’ Nutritional Needs? Cooking and Nutritional Knowledge and Habits in Medical Students. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2023, 17, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belogianni, K.; Ooms, A.; Lykou, A.; Moir, H.J. Nutrition Knowledge among University Students in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Study. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2834–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppoolse, H.L.; Seidell, J.C.; Dijkstra, S.C. Impact of Nutrition Education on Nutritional Knowledge and Intentions towards Nutritional Counselling in Dutch Medical Students: An Intervention Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Cattani, D.; Soekeland, F.; Axiak, G.; Mazzoleni, B.; De Marinis, M.G.; Piredda, M. Nutritional Knowledge of Nursing Students: A Systematic Literature Review. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 126, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzena, J.-Z.; Jan, G.; Lidia, W.; Jolanta, C.; Grzegorz, G.; Anna, K.-D.; Wojciech, R.; Agata, W.; Katarzyna, P.; Beata, S.; et al. KomPAN® Dietary Habits and Nutrition Beliefs Questionnaire for People 15–65 Years Old, Version 1.1.—Interviewer Administered Questionnaire. In KomPAN® Dietary Habits and Nutrition Beliefs Questionnaire and the Manual for Developing of Nutritional Data; The Committee of Human Nutrition, Polish Academy of Sciences: Olsztyn, Poland, 2020; Chapter 1; pp. 4–21. ISBN 978-83-950330-2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Galinski, G.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Bronkowska, M.; Dlugosz, A.; Loboda, D.; Wyka, J. Reproducibility of a Questionnaire for Dietary Habits, Lifestyle and Nutrition Knowledge Assessment (KomPAN) in Polish Adolescents and Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosendiak, A.A.; Adamczak, B.B.; Kuźnik, Z.; Makles, S. Impact of Medical School on the Relationship between Nutritional Knowledge and Sleep Quality—A Longitudinal Study of Students at Wroclaw Medical University in Poland. Nutrients 2024, 16, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, S.L.; Shields, S.A. The Body Esteem Scale: Multidimensional Structure and Sex Differences in a College Population. J. Personal. Assess. 1984, 48, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, M.; Lipowski, M. Polish Normalization of the Body Esteem Scale. Health Psychol. Rep. 2014, 1, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical Correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoza, R.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Garner, D. Analysis of the EAT-26 in a Non-Clinical Sample. Arch. Psych. Psych. 2016, 18, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk-Bisaga, K.; Dolan, B. A Two-Stage Epidemiological Study of Abnormal Eating Attitudes and Their Prospective Risk Factors in Polish Schoolgirls. Psychol. Med. 1996, 26, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faw, M.H.; Davidson, K.; Hogan, L.; Thomas, K. Corumination, Diet Culture, Intuitive Eating, and Body Dissatisfaction among Young Adult Women. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 28, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voges, M.M.; Giabbiconi, C.-M.; Schöne, B.; Waldorf, M.; Hartmann, A.S.; Vocks, S. Gender Differences in Body Evaluation: Do Men Show More Self-Serving Double Standards Than Women? Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 437146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Nunes, J.P.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Aguiar, A.F.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of Different Dietary Energy Intake Following Resistance Training on Muscle Mass and Body Fat in Bodybuilders: A Pilot Study. J. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 70, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallares, A. Drive for Thinness and Pursuit of Muscularity: The Role of Gender Ideologies. Univ. Psychol. 2016, 15, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, L. Diet Culture and Instagram: A Feminist Exploration of Perceptions and Experiences Among Young Women in the Midwest of Ireland. Grad. J. Gend. Glob. Right 2020, 1, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Most, J.; Redman, L.M. Impact of Calorie Restriction on Energy Metabolism in Humans. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 133, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollert, G.A.; Engel, S.G.; Schreiber-Gregory, D.N.; Crosby, R.D.; Cao, L.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Mitchell, J.E. The Role of Eating and Emotion in Binge Eating Disorder and Loss of Control Eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Spoor, S.; Bohon, C.; Veldhuizen, M.; Small, D. Relation of Reward from Food Intake and Anticipated Food Intake to Obesity: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008, 117, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cai, Z.; Fan, X. Prevalence of binge and loss of control eating among children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: An exploratory meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, E.K.; Thompson, L.A.; Knapik, J.J.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Lieberman, H.R.; Mcclung, J.P. Diet Quality Is Associated with Physical Performance and Special Forces Selection. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, C. Self-Esteem and Body Image Perception in a Sample of University Students. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2016, 16, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, Z.; King, T.K.; Morse, B.J. Virtual Ideals: The Effect of Video Game Play on Male Body Image. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İpek Kalender, G. The Portrayal of Ideal Beauty Both in the Media and in the Fashion Industry and How These Together Lead to Harmful Consequences Such as Eating Disorders. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Humanities, Psychology and Social Sciences, Berlin, Germany, 20 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jarman, H.K.; Marques, M.D.; McLean, S.A.; Slater, A.; Paxton, S.J. Social Media, Body Satisfaction and Well-Being among Adolescents: A Mediation Model of Appearance-Ideal Internalization and Comparison. Body Image 2021, 36, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchôa, F.N.M.; Uchôa, N.M.; Daniele, T.M.d.C.; Lustosa, R.P.; Garrido, N.D.; Deana, N.F.; Aranha, Á.C.M.; Alves, N. Influence of the Mass Media and Body Dissatisfaction on the Risk in Adolescents of Developing Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.P.; Malina, R.M.; Gomez-Campos, R.; Cossio-Bolaños, M.; Arruda, M.d.; Hobold, E. Body Mass Index and Physical Fitness in Brazilian Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutin, I. In BMI We Trust: Reframing the Body Mass Index as a Measure of Health. Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bator, E.; Habanova, M.; Broniecka, A.; Wyka, J.; Bronkowska, M. Porównanie Poziomu Wiedzy Żywieniowej Studentów Polskich i Słowackich w Zakresie Źródeł Pokarmowych Wybranych Składników Odżywczych. Available online: https://www.ptfarm.pl/wydawnictwa/czasopisma/bromatologia-i-chemia-toksykologiczna/117/-/15714 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Kosendiak, A.A.; Wysocki, M.; Krysiński, P.; Kuźnik, Z.; Adamczak, B. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity, Smoking, Alcohol Use, and Mental Well-Being—A Longitudinal Study of Nursing Students at Wroclaw Medical University in Poland. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1249509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumalla-Cano, S.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Aparicio-Obregón, S.; Crespo, J.; Eléxpuru-Zabaleta, M.; Gracia-Villar, M.; Giampieri, F.; Elío, I. Changes in the Lifestyle of the Spanish University Population during Confinement for COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, B.; Kuźnik, Z.; Makles, S.; Kosendiak, A. Physical activity of ukrainian and polish medical students in the beginning of the war in Ukraine. Health Probl. Civiliz. 2023, 17, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.D.; Alosaimi, F.M.; Alajlan, A.A.; Bin Abdulrahman, K.A. The Relationship between Sleep Quality, Stress, and Academic Performance among Medical Students. J. Fam. Community Med. 2020, 27, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.S.L.; Soh, N.L.; Walter, G.; Touyz, S. Comparison of Nutrition Knowledge among Health Professionals, Patients with Eating Disorders and the General Population. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 68, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkhasov, R.M.; Wong, J.; Kashanian, J.; Lee, M.; Samadi, D.B.; Pinkhasov, M.M.; Shabsigh, R. Are Men Shortchanged on Health? Perspective on Health Care Utilization and Health Risk Behavior in Men and Women in the United States. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolarzyk, E.; Shpakou, A.; Kleszczewska, E.; Klimackaya, L.; Laskiene, S. Nutritional Status and Food Choices among First Year Medical Students. Cent. Eur. J. Med. 2012, 7, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Fahimi, S.; Shi, P.; Powles, J.; Mozaffarian, D. Dietary Quality among Men and Women in 187 Countries in 1990 and 2010: A Systematic Assessment. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e132–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Kothe, E.J.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Efficacy of Psychotherapy for Bulimia Nervosa and Binge-Eating Disorder on Self-Esteem Improvement: Meta-Analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2019, 27, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C.; Glancy, D.; Pitts, A.; LeBlanc, V.R. Interventions to Reduce the Consequences of Stress in Physicians: A Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total. N = 879 [IQR]. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age mean | 19.4 [18.0–20.0] |

| Gender | |

| Male | 219 (24.9) |

| Female | 660 (75.1) |

| Place of residence | |

| Rural area | 199 (22.6) |

| City < 20,000 * | 90 (10.2) |

| City 20,000–100,000 * | 204 (23.2) |

| City 100,000+ * | 386 (43.9) |

| BMI | |

| Underweight | 99 (11.3) |

| Normal weight | 679 (77.3) |

| Overweight or obese | 101 (11.5) (from which 16 (1.82) were obese) |

| Female, N = 660 | Male, N = 219 | Female vs. Male | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | IQR | Mean | Median | IQR | p-Value | Z | |

| BMI | 21.23 | 20.8 | 19.3–22.6 | 23.02 | 22.9 | 21.0–24.3 | <0.0001 | 8.282 |

| DK | 12.92 | 14.0 | 10.0–16.0 | 12.62 | 14.0 | 10.0–16.0 | 0.6614 | 0.438 |

| DtSc | 10.80 | 9.36 | 1.5–19.1 | 2.97 | 1.7 | −4.26–9.28 | <0.0001 | 8.281 |

| DI | 8.19 | 6.0 | 3.0–12.0 | 7.13 | 5.0 | 2.0–9.0 | 0.0892 | 1.700 |

| B&FP | 2.37 | 1.0 | 0.0–3.0 | 2.01 | 0.0 | 0.0–3.0 | 0.2653 | 1.114 |

| OC | 3.14 | 2.0 | 0.0–5.0 | 3.03 | 2.0 | 0.0–4.0 | 0.9883 | 0.015 |

| SA | 48.10 | 48.0 | 41.0–55.0 | |||||

| WC | 35.72 | 36.0 | 30.0–43.0 | |||||

| PC | 31.56 | 31.0 | 27.0–37.0 | |||||

| PA | 41.56 | 40.0 | 34.0–50.0 | |||||

| UB | 33.02 | 33.0 | 27.0–39.0 | |||||

| PC | 47.87 | 48.0 | 39.0–56.0 | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Dieting Scale | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | 0.0864 (0.0084–0.1643) | 0.0854 (0.0079–0.1630) |

| Dietary Score | 0.0785 (0.0006–0.1565) | 0.0749 (−0.0027–0.1525) |

| BMI | 0.1052 (0.0296–0.1809) | |

| R2 | 0.0167 | 0.0277 |

| F | 5.5667 | 6.2336 |

| Bulimia and Food Preoccupation | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | 0.0113 (−0.0673–0.0899) | 0.0110 (−0.0676–0.0896) |

| Dietary Score | −0.0137 (−0.0923–0.0649) | −0.0150 (−0.0936–0.0636) |

| BMI | 0.0385 (−0.0382–0.1151) | |

| R2 | 0.0002 | 0.0017 |

| F | 0.0808 | 0.3776 |

| Oral Control | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.0074 (−0.0859–0.0712) | −0.0066 (−0.0850–0.0718) |

| Dietary Score | −0.0223 (−0.1008–0.0563) | −0.0195 (−0.0979–0.0589) |

| BMI | −0.0813 (−0.1577–−0.0048) | |

| R2 | 0.0006 | 0.0072 |

| F | 0.2048 | 1.5904 |

| Sexual Attractiveness | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | 0.0550 (−0.0234–0.1333) | 0.0565 (−0.0209–0.1338) |

| Dietary Score | 0.0422 (−0.0362–0.1206) | 0.0478 (−0.0296–0.1252) |

| BMI | −0.1652 (−0.2407–−0.0898) | |

| R2 | 0.0058 | 0.0331 |

| F | 1.9303 | 7.4855 |

| Weight Concern | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.0001 (−0.0786–0.0785) | 0.0030 (−0.0712–0.0771) |

| Dietary Score | 0.0302 (−0.0484–0.1088) | 0.0415 (−0.0327–0.1157) |

| BMI | −0.3333 (−0.4056–−0.2610) | |

| R2 | 0.0009 | 0.1118 |

| F | 0.2996 | 27.5299 |

| Physical Condition | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | 0.0366 (−0.0416–0.1147) | 0.0384 (−0.0382–0.1150) |

| Dietary Score | 0.0933 (0.0151–0.1714) | 0.1001 (0.0235–0.1768) |

| BMI | −0.2028 (−0.2775–−0.1281) | |

| R2 | 0.0116 | 0.0526 |

| F | 3.8429 | 12.1467 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Dieting Scale | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.2039 (−0.3326–−0.0752) | −0.2070 (−0.3341–−0.0799) |

| Dietary Score | 0.2673 (0.1385–0.3960) | 0.2493 (0.1215–0.3771) |

| BMI | 0.1656 (0.0390–0.2922 | |

| R2 | 0.0974 | 0.1245 |

| F | 11.6598 | 10.1931 |

| Bulimia and Food Preoccupation | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.2681 (−0.3987–−0.1375) | −0.2687 (−0.3995–−0.1379) |

| Dietary Score | 0.0704 (−0.0602–0.2010) | 0.0669 (−0.0647–0.1984) |

| BMI | 0.0324 (−0.0979–0.1627) | |

| R2 | 0.0714 | 0.0725 |

| F | 8.3096 | 5.6005 |

| Oral Control | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.2087 (−0.3412–−0.0762) | −0.2060 (−0.3374–−0.0746) |

| Dietary Score | 0.0603 (−0.0722–0.1928) | 0.0761 (−0.0561–0.2082) |

| BMI | −0.1453 (−0.2762–−0.0145) | |

| R2 | 0.0436 | 0.0645 |

| F | 4.9241 | 4.9382 |

| Physical Attractiveness | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.0164 (−0.1508–0.1179) | −0.0137 (−0.1470–0.1195) |

| Dietary Score | 0.1298 (−0.0046–0.2641) | 0.1457 (0.0117–0.2797) |

| BMI | −0.1466 (−0.2793–−0.0139 | |

| R2 | 0.0165 | 0.0377 |

| F | 1.8118 | 2.8092 |

| Upper Body Strength | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.0297 (−0.1633–0.1040) | −0.0294 (−0.1634–0.1045) |

| Dietary Score | 0.1669 (0.0332–0.3005) | 0.1682 (0.0335–0.3030) |

| BMI | −0.0128 (−0.1462–0.1206) | |

| R2 | 0.0273 | 0.0275 |

| F | 3.0320 | 2.0242 |

| Physical Condition | ||

| Dietary Knowledge | −0.0698 (−0.2036–0.0639) | −0.0668 (−0.1990–0.0654) |

| Dietary Score | 0.1560 (0.0223–0.2897) | 0.1739 (0.0410–0.3069) |

| BMI | −0.1650 (−0.2967–−0.0334) | |

| R2 | 0.0261 | 0.0530 |

| F | 2.8950 | 4.0110 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosendiak, A.A.; Adamczak, B.B.; Kuźnik, Z.; Makles, S. How Dietary Choices and Nutritional Knowledge Relate to Eating Disorders and Body Esteem of Medical Students? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101414

Kosendiak AA, Adamczak BB, Kuźnik Z, Makles S. How Dietary Choices and Nutritional Knowledge Relate to Eating Disorders and Body Esteem of Medical Students? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2024; 16(10):1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101414

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosendiak, Aureliusz Andrzej, Bartosz Bogusz Adamczak, Zofia Kuźnik, and Szymon Makles. 2024. "How Dietary Choices and Nutritional Knowledge Relate to Eating Disorders and Body Esteem of Medical Students? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 16, no. 10: 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101414

APA StyleKosendiak, A. A., Adamczak, B. B., Kuźnik, Z., & Makles, S. (2024). How Dietary Choices and Nutritional Knowledge Relate to Eating Disorders and Body Esteem of Medical Students? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 16(10), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101414