Acute Effects of Dietary Fiber in Starchy Foods on Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Crossover Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

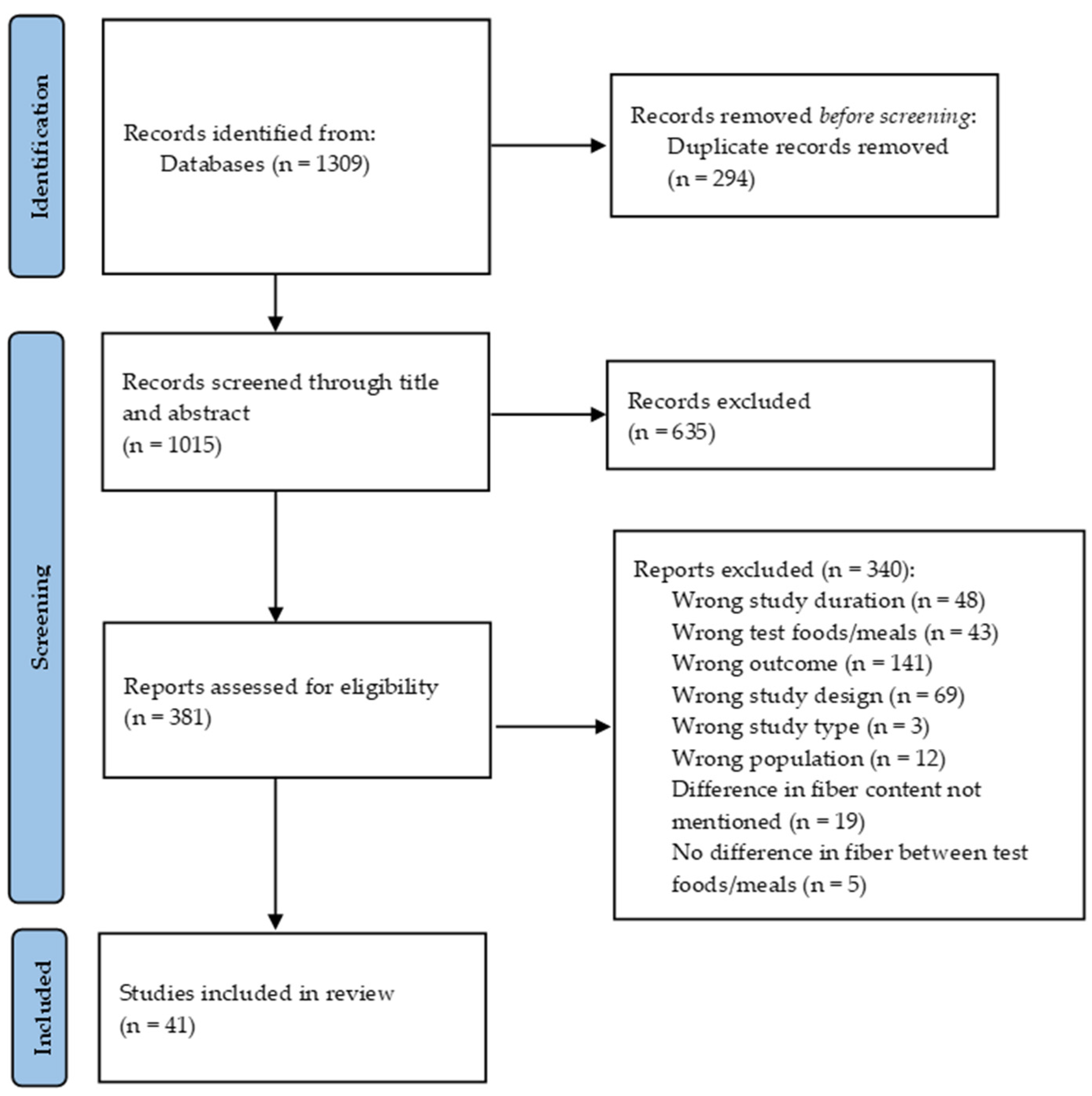

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

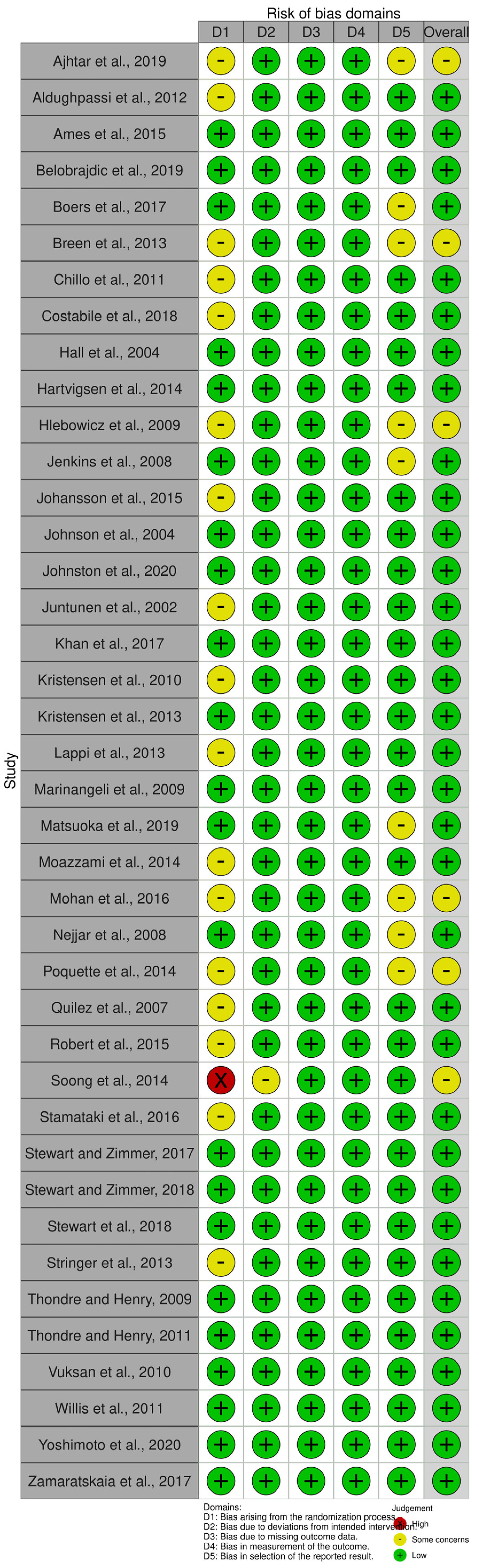

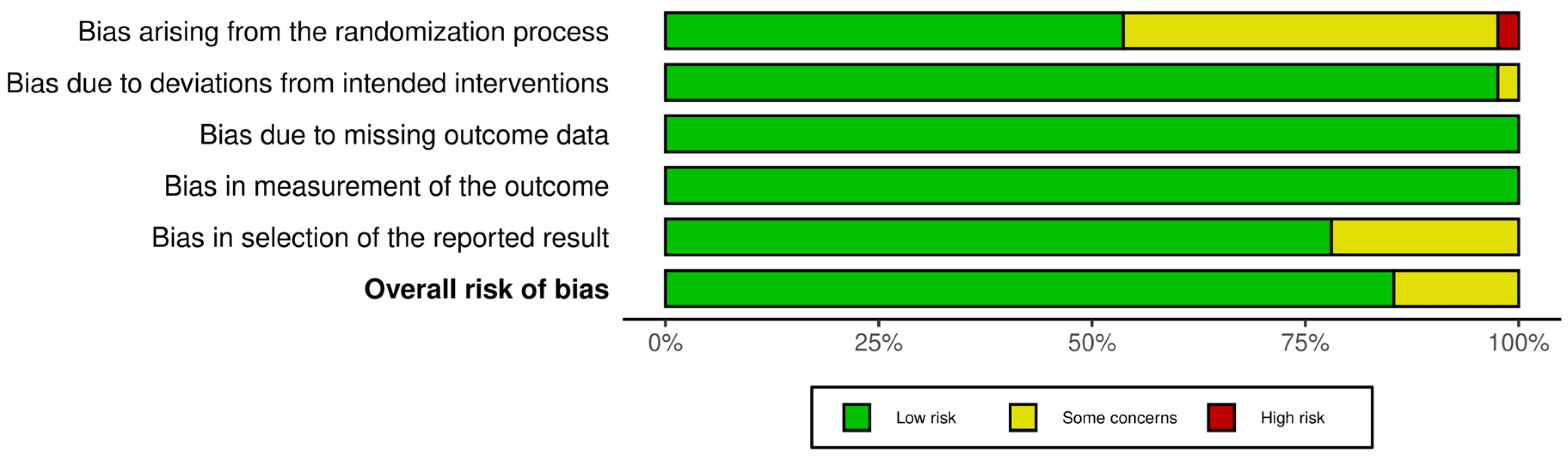

2.4. Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Main Exposures

3.3. Effects of Dietary Fiber on Glycemic Responses

3.3.1. Healthy Individuals

Normal Weight

Overweight and Obesity

3.3.2. Individuals with Different Health Conditions

3.4. Effects of Dietary Fiber on Insulinemic Responses

3.4.1. Healthy Individuals

Normal Weight

Overweight and Obesity

3.4.2. Individuals with Different Health Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shapira, N. The Metabolic Concept of Meal Sequence vs. Satiety: Glycemic and Oxidative Responses with Reference to Inflammation Risk, Protective Principles and Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, A.S. The epidemic of obesity and diabetes: Trends and treatments. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2011, 38, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Heart Association Nutrition Committee; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Brands, M.; Carnethon, M.; Daniels, S.; Franch, H.A.; Franklin, B.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Harris, W.S.; et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006, 114, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowell, H.; Southgate, D.A.; Wolever, T.M.; Leeds, A.R.; Gassull, M.A.; Jenkins, D.J. Letter: Dietary fibre redefined. Lancet 1976, 1, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.R.; Lineback, D.M.; Levine, M.J. Dietary reference intakes: Implications for fiber labeling and consumption: A summary of the International Life Sciences Institute North America Fiber Workshop, June 1–2, 2004, Washington, DC. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, G.A. Dietary Fiber, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungland, B.C.; Meyer, D. Nondigestible Oligo- and Polysaccharides (Dietary Fiber): Their Physiology and Role in Human Health and Food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2002, 1, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, A.M.; Champ, M.M.; Cloran, S.J.; Fleith, M.; van Lieshout, L.; Mejborn, H.; Burley, V.J. Dietary fibre in Europe: Current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes and relationships to health. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 149–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Mikkelsen, D.; Flanagan, B.M.; Gidley, M.J. “Dietary fibre”: Moving beyond the “soluble/insoluble” classification for monogastric nutrition, with an emphasis on humans and pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scazzina, F.; Siebenhandl-Ehn, S.; Pellegrini, N. The effect of dietary fibre on reducing the glycaemic index of bread. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weickert, M.O.; Pfeiffer, A.F. Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, W.J.; Stewart, M.L. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Health Implications of Dietary Fiber. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2015, 115, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S68–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. REGULATION (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32006R1924 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, D.; Michael, M.; Rajput, H.; Patil, R.T. Dietary fibre in foods: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.I.; Cummings, J.H. Possible implications for health of the different definitions of dietary fibre. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis 2009, 19, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesey, G.; Taylor, R.; Hulshof, T.; Howlett, J. Glycemic response and health—A systematic review and meta-analysis: The database, study characteristics, and macronutrient intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 223S–236S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, B.; Wen, L.; Wang, F.; Yu, H.; Chen, D.; Su, X.; Zhang, C. Effects of dietary fiber on human health. Food Sci Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasopoulos, A.; Camilleri, M. Dietary fiber supplements: Effects in obesity and metabolic syndrome and relationship to gastrointestinal functions. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 65–72.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemen, R.; de Vries, J.F.; Slavin, J.L. Relationship between molecular structure of cereal dietary fiber and health effects: Focus on glucose/insulin response and gut health. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T.K.; Mansell, K.M.; Knight, L.C.; Malmud, L.S.; Owen, O.E.; Boden, G. Long-term effects of dietary fiber on glucose tolerance and gastric emptying in noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 37, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, G.D.; Maratou, E.; Kountouri, A.; Board, M.; Lambadiari, V. Regulation of Postabsorptive and Postprandial Glucose Metabolism by Insulin-Dependent and Insulin-Independent Mechanisms: An Integrative Approach. Nutrients 2021, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weickert, M.O.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H. Impact of Dietary Fiber Consumption on Insulin Resistance and the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Munter, J.S.; Hu, F.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Franz, M.; van Dam, R.M. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, M.B.; Schulz, M.; Heidemann, C.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Boeing, H. Fiber and magnesium intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study and meta-analysis. AMA Arch. 2007, 167, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, T.; Huang, F.; Zhu, X.; Wei, D.; Chen, L. Effects of dietary fiber on glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 82, 104500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weickert, M.O.; Möhlig, M.; Schöfl, C.; Arafat, A.M.; Otto, B.; Viehoff, H.; Koebnick, C.; Kohl, A.; Spranger, J.; Pfeiffer, A.F. Cereal fiber improves whole-body insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese women. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Oikonomou, C.; Nychas, G.; Dimitriadis, G.D. Effects of Diet, Lifestyle, Chrononutrition and Alternative Dietary Interventions on Postprandial Glycemia and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, N.; Blewett, H.; Storsley, J.; Thandapilly, S.J.; Zahradka, P.; Taylor, C. A double-blind randomised controlled trial testing the effect of a barley product containing varying amounts and types of fibre on the postprandial glucose response of healthy volunteers. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chillo, S.; Ranawana, D.V.; Pratt, M.; Henry, C.J. Glycemic response and glycemic index of semolina spaghetti enriched with barley β-glucan. Nutrition 2011, 27, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Layla, A.; Sestili, P.; Ismail, T.; Afzal, K.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Asad, M. Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses of Vegetables and Beans Powders Supplemented Chapattis in Healthy Humans: A Randomized, Crossover Trial. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7425367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, C.; Ryan, M.; Gibney, M.J.; Corrigan, M.; O’Shea, D. Glycemic, insulinemic, and appetite responses of patients with type 2 diabetes to commonly consumed breads. Diabetes Educ. 2013, 39, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.; Jensen, M.G.; Riboldi, G.; Petronio, M.; Bügel, S.; Toubro, S.; Tetens, I.; Astrup, A. Wholegrain vs. refined wheat bread and pasta. Effect on postprandial glycemia, appetite, and subsequent ad libitum energy intake in young healthy adults. Appetite 2010, 54, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, M.; Savorani, F.; Christensen, S.; Engelsen, S.B.; Bügel, S.; Toubro, S.; Tetens, I.; Astrup, A. Flaxseed dietary fibers suppress postprandial lipemia and appetite sensation in young men. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldughpassi, A.; Abdel-Aal, e.-S.M.; Wolever, T.M. Barley cultivar, kernel composition, and processing affect the glycemic index. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1666–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.L.; Wilcox, M.L.; Bell, M.; Buggia, M.A.; Maki, K.C. Type-4 Resistant Starch in Substitution for Available Carbohydrate Reduces Postprandial Glycemic Response and Hunger in Acute, Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.L.; Zimmer, J.P. Postprandial glucose and insulin response to a high-fiber muffin top containing resistant starch type 4 in healthy adults: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Nutrition 2018, 53, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.L.; Zimmer, J.P. A High Fiber Cookie Made with Resistant Starch Type 4 Reduces Post-Prandial Glucose and Insulin Responses in Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2017, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinangeli, C.P.; Kassis, A.N.; Jones, P.J. Glycemic responses and sensory characteristics of whole yellow pea flour added to novel functional foods. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, S385–S389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabile, G.; Griffo, E.; Cipriano, P.; Vetrani, C.; Vitale, M.; Mamone, G.; Rivellese, A.A.; Riccardi, G.; Giacco, R. Subjective satiety and plasma PYY concentration after wholemeal pasta. Appetite 2018, 125, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juntunen, K.S.; Niskanen, L.K.; Liukkonen, K.H.; Poutanen, K.S.; Holst, J.J.; Mykkänen, H.M. Postprandial glucose, insulin, and incretin responses to grain products in healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H.J.; Thomas, W.; Eldridge, A.L.; Harkness, L.; Green, H.; Slavin, J.L. Glucose and insulin do not decrease in a dose-dependent manner after increasing doses of mixed fibers that are consumed in muffins for breakfast. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, S.D.; Ismail, A.A.; Rosli, W.I. Reduction of postprandial blood glucose in healthy subjects by buns and flatbreads incorporated with fenugreek seed powder. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2275–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thondre, P.S.; Henry, C.J. High-molecular-weight barley beta-glucan in chapatis (unleavened Indian flatbread) lowers glycemic index. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thondre, P.S.; Henry, C.J. Effect of a low molecular weight, high-purity β-glucan on in vitro digestion and glycemic response. Int. J. Food Sci. 2011, 62, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, V.; Anjana, R.M.; Gayathri, R.; Ramya Bai, M.; Lakshmipriya, N.; Ruchi, V.; Balasubramaniyam, K.K.; Jakir, M.M.; Shobana, S.; Unnikrishnan, R.; et al. Glycemic Index of a Novel High-Fiber White Rice Variety Developed in India—A Randomized Control Trial Study. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2016, 18, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebowicz, J.; Jönsson, J.M.; Lindstedt, S.; Björgell, O.; Darwich, G.; Almér, L.O. Effect of commercial rye whole-meal bread on postprandial blood glucose and gastric emptying in healthy subjects. Nutr. J. 2009, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.L.; Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Rogovik, A.L.; Jovanovski, E.; Bozikov, V.; Rahelić, D.; Vuksan, V. Comparable postprandial glucose reductions with viscous fiber blend enriched biscuits in healthy subjects and patients with diabetes mellitus: Acute randomized controlled clinical trial. Croat Med. J. 2008, 49, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, D.M.; Taylor, C.G.; Appah, P.; Blewett, H.; Zahradka, P. Consumption of buckwheat modulates the post-prandial response of selected gastrointestinal satiety hormones in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2013, 62, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvigsen, M.L.; Gregersen, S.; Lærke, H.N.; Holst, J.J.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Hermansen, K. Effects of concentrated arabinoxylan and β-glucan compared with refined wheat and whole grain rye on glucose and appetite in subjects with the metabolic syndrome: A randomized study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, D.P.; Lee, I.; Risérus, U.; Langton, M.; Landberg, R. Effects of unfermented and fermented whole grain rye crisp breads served as part of a standardized breakfast, on appetite and postprandial glucose and insulin responses: A randomized cross-over trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamataki, N.S.; Nikolidaki, E.K.; Yanni, A.E.; Stoupaki, M.; Konstantopoulos, P.; Tsigkas, A.P.; Perrea, D.; Tentolouris, N.; Karathanos, V.T. Evaluation of a high nutritional quality snack based on oat flakes and inulin: Effects on postprandial glucose, insulin and ghrelin responses of healthy subjects. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuksan, V.; Jenkins, A.L.; Dias, A.G.; Lee, A.S.; Jovanovski, E.; Rogovik, A.L.; Hanna, A. Reduction in postprandial glucose excursion and prolongation of satiety: Possible explanation of the long-term effects of whole grain Salba (Salvia Hispanica L.). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, Y.Y.; Quek, R.Y.; Henry, C.J. Glycemic potency of muffins made with wheat, rice, corn, oat and barley flours: A comparative study between in vivo and in vitro. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 1281–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamaratskaia, G.; Johansson, D.P.; Junqueira, M.A.; Deissler, L.; Langton, M.; Hellström, P.M.; Landberg, R. Impact of sourdough fermentation on appetite and postprandial metabolic responses—A randomised cross-over trial with whole grain rye crispbread. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, H.M.; MacAulay, K.; Murray, P.; Dobriyal, R.; Mela, D.J.; Spreeuwenberg, M.A. Efficacy of fibre additions to flatbread flour mixes for reducing post-meal glucose and insulin responses in healthy Indian subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, T.; Tsuchida, A.; Yamaji, A.; Kurosawa, C.; Shinohara, M.; Takayama, I.; Nakagomi, H.; Izumi, K.; Ichikawa, Y.; Hariya, N.; et al. Consumption of a meal containing refined barley flour bread is associated with a lower postprandial blood glucose concentration after a second meal compared with one containing refined wheat flour bread in healthy Japanese: A randomized control trial. Nutrition 2020, 72, 110637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belobrajdic, D.P.; Regina, A.; Klingner, B.; Zajac, I.; Chapron, S.; Berbezy, P.; Bird, A.R. High-Amylose Wheat Lowers the Postprandial Glycemic Response to Bread in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, J.; Kato, Y.; Ban, M.; Kishi, M.; Horie, H.; Yamada, C.; Nishizaki, Y. Palatable Noodles as a Functional Staple Food Made Exclusively from Yellow Peas Suppressed Rapid Postprandial Glucose Increase. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazzami, A.A.; Shrestha, A.; Morrison, D.A.; Poutanen, K.; Mykkänen, H. Metabolomics reveals differences in postprandial responses to breads and fasting metabolic characteristics associated with postprandial insulin demand in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quílez, J.; Bulló, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Improved postprandial response and feeling of satiety after consumption of low-calorie muffins with maltitol and high-amylose corn starch. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, S407–S411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Shah, S.; Ahmad, J.; Abdullah, A.; Johnson, S.K. Effect of Incorporating Bay Leaves in Cookies on Postprandial Glycemia, Appetite, Palatability, and Gastrointestinal Well-Being. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappi, J.; Aura, A.M.; Katina, K.; Nordlund, E.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkänen, H.; Poutanen, K. Comparison of postprandial phenolic acid excretions and glucose responses after ingestion of breads with bioprocessed or native rye bran. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poquette, N.M.; Gu, X.; Lee, S.O. Grain sorghum muffin reduces glucose and insulin responses in men. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.K.; Thomas, S.J.; Hall, R.S. Palatability and glucose, insulin and satiety responses of chickpea flour and extruded chickpea flour bread eaten as part of a breakfast. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, A.M.; Parsons, P.M.; Duncan, A.M.; Robinson, L.E.; Yada, R.Y.; Graham, T.E. The acute impact of ingestion of breads of varying composition on blood glucose, insulin and incretins following first and second meals. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.J.; Mollard, R.C.; Dandeneau, D.; MacKay, D.S.; Ames, N.; Curran, J.; Bouchard, D.R.; Jones, P.J. Acute effects of extruded pulse snacks on glycemic response, insulin, appetite, and food intake in healthy young adults in a double blind, randomized, crossover trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.S.; Thomas, S.J.; Johnson, S.K. Australian sweet lupin flour addition reduces the glycaemic index of a white bread breakfast without affecting palatability in healthy human volunteers. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Xaidara, M.; Siopi, V.; Giannoglou, M.; Katsaros, G.; Theodorou, G.; Maratou, E.; Poulia, K.A.; Dimitriadis, G.D.; Skandamis, P.N. Effects of Spaghetti Differing in Soluble Fiber and Protein Content on Glycemic Responses in Humans: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Healthy Subjects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.N.; Mann, J.; Elbalshy, M.; Mete, E.; Robinson, C.; Oey, I.; Silcock, P.; Downes, N.; Perry, T.; Te Morenga, L. Wholegrain Particle Size Influences Postprandial Glycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Study Comparing Four Wholegrain Breads. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 476–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.M.; Kramer, C.K.; de Almeida, J.C.; Steemburgo, T.; Gross, J.L.; Azevedo, M.J. Fiber intake and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.; Liu, S.; Solomon, C.G.; Willett, W.C. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N. Eng. J. Med. 2001, 345, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerich, J.E. Is reduced first-phase insulin release the earliest detectable abnormality in individuals destined to develop type 2 diabetes? Diabetes 2002, 51 (Suppl. S1), S117–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.; Boutati, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Mitrou, P.; Maratou, E.; Brunel, P.; Raptis, S.A. Restoration of early insulin secretion after a meal in type 2 diabetes: Effects on lipid and glucose metabolism. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 34, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, G.; Rivellese, A.A. Effects of dietary fiber and carbohydrate on glucose and lipoprotein metabolism in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1991, 14, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regand, A.; Chowdhury, Z.; Tosh, S.M.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Wood, P. The molecular weight, solubility and viscosity of oat beta-glucan affect human glycemic response by modifying starch digestibility. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of a health claim related to oat beta-glucan and lowering blood cholesterol and reduced risk of (coronary) heart disease pursuant to Article 14 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. J. EFSA 2010, 8, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Health claims: Fiber-containing grain products, fruits, and vegetables and cancer. Fed. Regist. 1993, 58, 2548. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, I.H.; Albrink, M.J. The effect of dietary fiber and other factors on insulin response: Role in obesity. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 1985, 5, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, C.S.; Blake, D.E.; Ellis, P.R.; Schofield, J.D. Effects of guar galactomannan on wheat bread microstructure and on the in vitro and in vivo digestibility of starch in bread. J. Cereal. Sci. 1996, 24, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyechi, U.A.; Judd, P.A.; Ellis, P.R. African plant foods rich in non-starch polysaccharides reduce postprandial blood glucose and insulin concentrations in healthy human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 1998, 80, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, G.D.; Tessari, P.; Go, V.L.; Gerich, J.E. alpha-Glucosidase inhibition improves postprandial hyperglycemia and decreases insulin requirements in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1985, 34, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.; Hatziagellaki, E.; Alexopoulos, E.; Kordonouri, O.; Komesidou, V.; Ganotakis, M.; Raptis, S. Effects of alpha-glucosidase inhibition on meal glucose tolerance and timing of insulin administration in patients with type I diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1991, 14, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, K.S.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Autio, K.; Niskanen, L.K.; Holst, J.J.; Savolainen, K.E.; Liukkonen, K.H.; Poutanen, K.S.; Mykkänen, H.M. Structural differences between rye and wheat breads but not total fiber content may explain the lower postprandial insulin response to rye bread. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, K.; Liukkonen, K.; Poutanen, K.; Uusitupa, M.; Mykkanen, H. Rye bread decreases postprandial insulin response but does not alter glucose response in healthy Finnish subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, H.D.; Repin, N.; Fabek, H.; El Khoury, D.; Gidley, M.J. Dietary fibre for glycaemia control: Towards a mechanistic understanding. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet Fibre 2018, 14, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würsch, P.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X. The role of viscous soluble fiber in the metabolic control of diabetes. A review with special emphasis on cereals rich in beta-glucan. Diabetes Care 1997, 20, 1774–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Leeds, A.R.; Gassull, M.A.; Haisman, P.; Dilawari, J.; Goff, D.V.; Metz, G.L.; Alberti, K.G. Dietary fibres, fibre analogues, and glucose tolerance: Importance of viscosity. Br. Med. J. 1978, 1, 1392–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuntini, E.B.; Sarda, F.A.H.; de Menezes, E.W. The Effects of Soluble Dietary Fibers on Glycemic Response: An Overview and Futures Perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaridou, A.; Biliaderis, C.G. Molecular aspects of cereal β-glucan functionality: Physical properties, technological applications and physiological effects. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to beta-glucans from oats and barley and maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1236, 1299), increase in satiety leading to a reduction in energy intake (ID 851, 852), reduction of post-prandial glycaemic responses (ID 821, 824), and “digestive function” (ID 850) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. J. EFSA 2011, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar]

- Samra, R.A.; Anderson, G.H. Insoluble cereal fiber reduces appetite and short-term food intake and glycemic response to food consumed 75 min later by healthy men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weickert, M.O.; Mohlig, M.; Koebnick, C.; Holst, J.J.; Namsolleck, P.; Ristow, M.; Osterhoff, M.; Rochlitz, H.; Rudovich, N.; Spranger, J.; et al. Impact of cereal fibre on glucose-regulating factors. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 2343–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, S.J.; Ellis, P.R.; Morgan, L.M.; Judd, P.A. Effect of partially depolymerized guar gum on acute metabolic variables in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes Med. 1996, 13, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, S.; Davidson, C.J.; Zderic, T.W.; Byerley, L.O.; Coyle, E.F. Different glycemic indexes of breakfast cereals are not due to glucose entry into blood but to glucose removal by tissue. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, C.M.; Tia, M.R. Fiber and Insulin Sensitivity. In Topics in the Prevention, Treatment and Complications of Type 2 Diabetes; Mark, B.Z., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Italy, 2011; p. Ch. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Weening, D.; Jonkers, E.; Boer, T.; Stellaard, F.; Small, A.C.; Preston, T.; Vonk, R.J.; Priebe, M.G. A curve fitting approach to estimate the extent of fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 38, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Q.; Tian, B.; Nie, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Health beneficial effects of resistant starch on diabetes and obesity via regulation of gut microbiota: A review. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5749–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenu, M.; Xu, B. A critical review on anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effects of dietary resistant starch. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3019–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostman, E.M.; Liljeberg Elmståhl, H.G.; Björck, I.M. Barley bread containing lactic acid improves glucose tolerance at a subsequent meal in healthy men and women. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1173–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brighenti, F.; Benini, L.; Del Rio, D.; Casiraghi, C.; Pellegrini, N.; Scazzina, F.; Jenkins, D.J.; Vantini, I. Colonic fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates contributes to the second-meal effect. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.E.; Mandarino, L.J. Fuel selection in human skeletal muscle in insulin resistance: A reexamination. Diabetes 2000, 49, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, J.; Sargsyan, E.; Bergsten, P. Fatty acids stimulate insulin secretion from human pancreatic islets at fasting glucose concentrations via mitochondria-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, E.; Barrett, E.J.; Bevilacqua, S.; DeFronzo, R.A. Effect of fatty acids on glucose production and utilization in man. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 72, 1737–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Salhy, M.; Ystad, S.O.; Mazzawi, T.; Gundersen, D. Dietary fiber in irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Fahey, G.C.; Garleb, K.A. Perspective: Physiologic Importance of Short-Chain Fatty Acids from Nondigestible Carbohydrate Fermentation. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.J. Protein: Metabolism and effect on blood glucose levels. Diabetes Educ. 1997, 23, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, G.; O’Dea, K. The effect of coingestion of fat on the glucose, insulin, and gastric inhibitory polypeptide responses to carbohydrate and protein. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 37, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Wong, G.S.; Kenshole, A.; Josse, R.G.; Thompson, L.U.; Lam, K.Y. Glycemic responses to foods: Possible differences between insulin-dependent and noninsulin-dependent diabetics. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 40, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Country | Study Design and Duration (min) | Health Status Sample Size Age (Years) Sex BMI (kg/m2) | Type of Dietary Fiber | Test Meals (Macronutrients and Dietary Fiber Analysis) | Glycemic Responses | Insulinemic Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juntunen et al., 2002 [44] | Finland | RX 180 | Healthy subjects 20 28.0 ± 1.0 10Μ:10F 22.9 ± 0.7 | Oat β-glucan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Wheat WB as reference food (TDF: 3.1 g, 0.9 g soluble, 2.0 g pentosan, 0.2 g β-glucan/Pr: 8.4 g/L: 3.0 g) Whole-kernel rye bread (WKRB) (60% whole rye kernels and 40% rye flour) (TDF: 12.8 g, 3.8 g soluble, 8.7 g pentosan, 1.3 g β-glucan/Pr: 7.4 g/L: 2.6 g) β-Glucan rye bread (RB) (20% oat β-glucan and 80% rye flour) (TDF: 17.1 g, 6.8 g soluble, 10.3 g, pentosan, 5.4 g β-glucan/Pr: 10.5 g/L: 2.4 g) + 40 g cucumber + 0.3 L non-energy-containing orange drink Whole-meal pasta (WMP) (dark durum wheat) (TDF: 5.6 g, 1.3 g soluble, NM g pentosan, NA g β-glucan/Pr: 12.1 g/L: 4.7 g) + 19 g crushed tomatoes, 0.3 L non-energy-containing orange drink | β-Glucan RB vs. wheat WB: ↑ GR at 120 min WMP vs. wheat WB: ↑ GR at 120, 150, 180 min WMP vs. wheat WB: ↓ maximal GR | WKRB vs. wheat WB: ↓ InsR at 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150 min β-Glucan RB vs. wheat WB: ↓ InsR at 45, 60, 120, 150, 180 min WKRB, β-glucan RB, WMP vs. wheat WB: ↓ maximal InsR WKRB, WMP vs. wheat WB: Smaller PPI areas above fasting levels |

| Hall et al., 2005 [71] | Australia | RX, single-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 11 31.6 ± 1.8 9M:2F 24.7 ± 0.8 | Soluble and insoluble DF | (50 g AVCHO) Breakfast with WB (TDF: 2.8 g/Pr: 9.2 g/L: 6.4 g) Breakfast with Australian Sweet Lupin Flour Bread (ASLF) (TDF: 4.9 g/Pr: 12.8 g/L: 7.3 g) + 6 g low-fat margarine, 20 g low-joule apricot spread, a cup of decaffeinated tea with 30 g skim milk | ASLF (GI = 52) vs. WB (GI = 100): ↓ GI | ASLF vs. WB: ↑ Ins index |

| Johnson et al., 2005 [68] | Australia | RX, single-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 12 32.0 ± 2.0 10M:2F 24.7 ± 0.8 | RS | (50 g AVCHO) WB (TDF: 3.0 g/Pr: 9.0 g/L: 6.0 g) Chickpea bread (CHB) (TDF: 5.0 g/Pr: 11.0 g/L: 7.0 g) Extruded chickpea bread (EXB) (TDF: 6.0 g/Pr: 11.0 g/L: 7.0 g) + margarine, jam, milk, and tea | CHB vs. WB: ↓ GR at 90 min Trend toward ↓ iAUC EXB vs. WB: ↓ GR at 120 min ND in GI between test meals | WB, EXB vs. CHB: peak at 30 vs. 45 min CHB vs. WB, EXB: ↑ InsR at 60 min CHB vs. WB: ↑ Ins iAUC ↑ Ins index |

| Quilez et al., 2007 [64] | Spain | RX 120 | Healthy subjects 14 33.1 ± 7.8 7M:7M 25.8 ± 2.9 Group 1 (normal): 20 to 24.9 Group 2 (overweight): 25 to 29.9 | Carboxy-methyl cellulose and guar gum (soluble DF) High-amylose corn starch (RS) | (50 g AVCHO) Bread as reference food (TDF: 2.7%/CHO: 56.5%/Pr: 8.8%/L: 0.7%) Plain muffin (PM) (TDF: 1.5%/CHO: 47.9%/Pr: 4.8%/L: 21.2%) Low-calorie muffin (LCM) (TDF: 6.3%/CHO: 49.2%/Pr: 5.0%/L: 10.3%) | Bread vs. LCM: Differences in GR Bread, LCM vs. PM: ND in GR Overweight vs. normal: ↑ GR with bread and LCM ND in GR with PMs LCM vs. bread: ↓ 51.8% GR | Bread, PM vs. LCM: ↑ InsR PM, bread vs. LCM: ↑ 69.7% and ↑ 63.3% InsR |

| Jenkins et al., 2008 [51] | Canada | RX single-blind Trial 1: 90 Trial 2: 180 | Trial 1: Healthy participants 10 28.0 ± 2.6 4M:6F 24.3 ± 0.8 Trial 2: Participants with T2DM 9 68.0 ± 3.8 3M:6F 28.8 ± 1.2 | PGX: Glucomannan (soluble DF) Xanthan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) C Biscuit (CB) (TDF: 1.7 g/CHO: 51.8 g/Pr: 4.5 g/L: 10.2 g) Biscuit with 10 g of fiber blend (FB) (TDF: 11.6 g/CHO: 63.1 g/Pr: 4.3 g/L: 10.9 g) WB (TDF: 2.5 g/CHO: 52.6 g/Pr: 8.3 g/L: 0.4 g) WB with 12 g of margarine (WBM) (TDF: 2.5 g/CHO: 52.6 g/Pr: 8.4 g/L: 10.0 g) | Trial 1: FB (GI = 26) vs. CB (GI = 101), WB, WBM (GI = 108): ↓ 74% GI FB vs. WB: ↓ GR at 30, 45, 60, 90 min ND in GR between CB, WB, and WBM Trial 2: FB (GI = 37) vs. CB (GI = 94), WB, WBM (GI = 103): ↓ 63% GI FB vs. WB: ↓ GR at 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180 min ND in GR between CB, WB and WBM | NA |

| Hlebowicz et al., 2009 [50] | Sweden | RX 90 | Healthy subjects 10 26.0 ± 1.0 3M:7F 24.1 ± 0.8 | Rye β-glucan and arabino-xylan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO per meal) WB (TDF: 0.0 g/AVCHO: 52.0 g/Pr: 13.5 g/L: 0.0 g) Rye whole-meal bread (TDF: 3.75 g/AVCHO: 62.7 g/Pr: 12.75 g/L: 4.5 g) + ham, 300 mL FUN Light fruit drink | ND in GR and iAUC between test meals | NA |

| Marinangeli et al., 2009 [42] | Canada | RX, single-blind 150 | Healthy individuals 19 22–67 7M:12F 21–42 | Soluble and insoluble DF | (50 g AVCHO) WB as reference food Boiled yellow peas (BYP) as reference food Banana bread with whole yellow pea flour (WYPF) (TDF: 8.1 g, 3.0 g soluble, 5.1 g insoluble/CHO: 52.0 g/Pr: 9.3 g/L: 15.2 g) Banana bread with WWF (TDF: 7.1 g, 3.1 g soluble, 4.0 g insoluble/CHO: 51.7 g/Pr: 7.8 g/L: 16.1 g) Biscotti with WYPF (TDF: 10.1 g, 3.3 g soluble, 6.4 g insoluble/CHO: 51.7 g/Pr: 12.2 g/L: 13.3 g) Biscotti with WWF (TDF: 8.2 g, 3.3 g soluble, 4.4 g insoluble/CHO: 53.2 g/Pr: 9.5 g/L: 13.3 g) Spaghetti with 30% WYPF and 70% white wheat durum (TDF: 8.1 g, 3.4 g soluble, 4.8 g insoluble/CHO: 51.1 g/Pr: 7.4 g/L: 1.6 g) Spaghetti with 100% whole-wheat durum (TDF: 6.6 g, NA g soluble or insoluble/CHO: 51.1 g/Pr: 9.9 g/L: 1.2 g) | WYPF biscotti and WYPF banana bread vs. WB: ↓ 61.9% and 55.1% iAUC WYPF spaghetti vs. BYP: ↑ 43.1% iAUC ND in iAUC between WYPF and WWF spaghetti WYPF vs. WWF biscotti: ↓ 29.2% iAUC WYPF biscotti (GI = 45.4), WYPF banana bread (GI = 50.3) vs. WYPF spaghetti (GI = 93.3): ↓ GI WYPF biscotti (GI = 45.4) vs. WWF biscotti (GI = 63.9): ↓ GI | NA |

| Najjar et al., 2009 [69] | Canada | RX, single-blind 180 | Overweight or obese males 11 59.0 ± 2.41 11M 30.8 ± 0.95 | β-Glucan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) WB (TDF: 1.5 g/Pr: 9.7 g/L: 4.2 g) Whole-wheat bread (WWB) (TDF: 6.3 g/Pr: 16.0 g/L: 6.1 g) Sourdough bread (SB) (TDF: 1.0 g/Pr: 9.8 g/L: 4.7 g) Whole-wheat barley bread (WWBB) (TDF: 6.1 g/Pr: 15.1 g/L: 6.1 g) | SB vs. WB, WWB: ↓ GR WWBB vs. WWB: ↓ GR SB vs. WWB: ↓ Glu AUC | ND in InsR, Ins AUC, and Ins sensitivity index between test meals |

| Thondre and Henry, 2009 [47] | United Kingdom | RX, single-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 8 38.0 ± 11.0 3M:5F 23.2 ± 3.5 | Barley β-glucan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food 5 chapattis (CH) containing 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 g of β-glucan (+WWF) CH0 (TDF: 9.1 g, 0 g β-glucan/CHO: 59.1 g/Pr: 10.9 g/L: 1.5 g) CH2 (TDF: 11.3 g, 2 g β-glucan/CHO: 62.5 g/Pr: 11.9 g/L: 1.64 g) CH4 (TDF: 13.1 g, 4 g β-glucan/CHO: 63.2 g/Pr: 12.4 g/L: 1.7 g) CH6 (TDF: 15.2 g, 6 g β-glucan/CHO: 65.2 g/Pr: 13.1 g/L: 1.7 g) CH8 (TDF: 17.2 g, 6 g β-glucan/CHO: 67.0 g/Pr: 13.8 g/L: 1.8 g) | CH2, CH4, CH6, CH8 vs. Glu: ↓ GR ND in GR between CH0 and CH2 CH4: ↓ GR at 45 min CH8: ↓ GR at 45 and 60 min CH4 and CH8 vs. CH0: ↓ GI CH0, CH2, CH4, CH6, CH8 vs. Glu: ↓ Glu iAUC0–120 CH4, CH8 vs. CH0: ↓ Glu iAUC0–120 CH0, CH2, CH4, CH6, CH8 vs. Glu: ↓ ΔGlu at 15, 30, 45 min CH4 and CH8 vs. CH0: ↓ 43% and 47% GI Glu: peak time at 30 min CH0, CH2, CH6: peak time at 45 min CH4: peak time at 60 min CH8: peak time at 30 min and maintained until 60 min | NA |

| Kristensen et al., 2010 [36] | Denmark | RX open-labeled 180 | Young healthy adults 16 24.1 ± 3.8 6M:10F 21.7 ± 2.2 | Arabinoxylans (soluble DF) | 4 isocaloric meals (50 g AVCHO per meal) WB (TDF: 3.9 g/CHO: 45% of E/Pr: 20.5% of E/L: 34.4% of E) Wholegrain WB (WWB) (TDF: 11.7 g/CHO: 51.7% of E/Pr: 19.8% of E/L: 28.4% of E) Refined wheat pasta (RWP) (TDF: 2.2 g/CHO: 44.1% of E/Pr: 21.3% of E/L: 34.5% of E) Wholegrain pasta (WWP) (TDF: 5.0 g/CHO: 48.2% of E/Pr: 21% of E/L: 30.9% of E) + cheese | ND in GR between bread meals or pasta meals at any time point WB vs. RWP: ↑ GR at 30, 45, 60, 90 min ↑ Glu AUC WWB vs. WWP: ↑ GR at 45 and 60 min ↑ Glu AUC RWP vs. WB: ↓ GI | NA |

| Vuksan et al., 2010 [56] | Canada | RX, double-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 11 30.0 ± 3.6 6M:7F 22.2 ± 1.3 | NM | (50 g AVCHO) WB (TDF: 2.1 g/CHO: 52.1 g/Pr: 9.4 g/L: 0.7 g) Low-Salba-dose bread (LSB) (TDF: 4.9 g/CHO: 54.9 g/Pr: 11.11 g/L: 3.1 g) Intermediate-Salba-dose bread (ISB) (TDF: 8.1 g/CHO: 58.1 g/Pr: 13.1 g/L: 5.7 g) High-Salba-dose bread (HSB) (TDF: 11.7 g/CHO: 61.7 g/Pr: 15.3 g/L: 8.7 g) | LSB, ISB, HSB vs. WB: ↓ 41%, 28%, and 21% iAUC HSD vs. WB: ↓ GR at 30, 45, 60 min ISB vs. WB: ↓ GR at 60 min LSB vs. WB: ↓ GR at 45 min | NA |

| Chillo et al., 2011 [33] | United Kingdom | RX 120 | Healthy subjects 9 35.0 ± 11.6 3M:6F 21.7 ± 4.1 | GlucaGel (GG): 79.4% low-molecular-weight β-glucan (soluble DF) Barley Balance (BB): 26.5% high-molecular-weight β-glucan (soluble DF), 10% other DF | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food Spaghetti samples: 0GG/0BB (WDS) 2GG (2%GG + WDS) 4GG (4%GG + WDS) 6GG (6%GG + WDS) 8GG (8%GG + WDS) 10GG (10%GG + WDS) 2BB (2%BB + WDS) 4BB (4%BB + WDS) 6BB (6%BB + WDS) 8BB (8%BB + WDS) 10BB (10%BB + WDS) | All GG spaghetti vs. Glu: ↓ GR at 15, 30, 45 min 4GG, 6GG, 8GG, 10GG vs. Glu: ↓ GR at 60 min Similar GR at 90 and 120 min Glu and all GG spaghetti: Peak time at 30 min All BB spaghetti vs. Glu: ↓ GR at 15, 30, 45 min 4BB, 6BB, 8BB, 10BB vs. Glu: ↓ GR at 60 min BB: peak time at 45 min All GG spaghetti vs. Glu: ↓ iAUC (mean ↓ 47%) 6GG and 10GG vs. Glu: ↓ 32.6% and 29.5% iAUC All BB spaghetti vs. Glu: ↓ iAUC (mean ↓ 60%) 10BB vs. 0BB: ↓ 51.6% iAUC ↑ %BB → ↓ GI 10BB vs. 0BB: ↓ 55% GI | NA |

| Thondre and Henry, 2011 [48] | United Kingdom | RX, single-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 10 35.0 ± 7.5 6M:4F 23.1 ± 2.4 | GGTM as source of β-glucan (75% β-glucan) (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food Chapatti with 0% β-glucan (TDF: 9.1 g/CHO: 59.0 g/Pr: 10.9 g/L: 1.5 g) Chapatti with 4% β-glucan (TDF: 12.6 g, 4 g β-glucan/CHO: 60.0 g/Pr: 10.5 g/L: 1.5 g) Chapatti with 8% β-glucan (TDF: 14.3 g, 8 g β-glucan/CHO: 61.0 g/Pr: 10.1 g/L: 1.5 g) | ND in iAUC between test meals 0, 4, 8% chapattis vs. Glu: ↓ AUCs ND in AUCs between chapatti samples 4% (GI = 55), 8% (GI = 52) vs. 0% (GI = 58) chapatti: ↓ GI | NA |

| Willis et al., 2011 [45] | USA | RX, double-blind 180 | Healthy subjects 20 26.0 ± 7.0 10M:10F 24.0 ± 2.0 | Mixed soluble DF: pectin, barley β-glucan, guar gum, pea fiber, and citrus fiber | 4 muffins (MUF) containing 0, 4, 8, and 12 g of mixed fiber MUFF0 (TDF: <1.0 g, ΝA g soluble or insoluble/CHO: 74.0 g/Pr: 11.0 g/L: 20.0 g) MUFF4 (TDF: 6.0 g, 3.0 g soluble, 3.0 g insoluble/CHO: 81.0 g/Pr: 12.0 g/L: 13.0 g) MUFF8 (TDF: 9.0 g, 4.0 g soluble, 5.0 g insoluble/CHO: 89.0 g/Pr: 12.0 g/L: 10.0 g) MUFF12 (TDF: 13.0 g, 6.0 g soluble, 7.0 g insoluble/CHO: 93.0 g/Pr: 13.0 g/L: 13.0 g) | MUFF0 vs. MUFF4, MUFF8, MUFF12: ↓ Glu AUC ↓ mean change in peak Glu from baseline ↑ dose → ↑ Glu AUC MUFF12 vs. MUFF4, MUFF8: ↓ mean change in peak Glu from baseline | MUFF4 vs. MUFF0, MUFF8, MUFF12: ↑ Ins AUC ND in mean change in peak Ins from baseline between test meals |

| Aldughpassi et al., 2012 [38] | Canada | RX 120 | Healthy participants 10 40.6 ± 2.7 4M:6F 27.6 ± 1.2 | β-Glucan (soluble) | (50 g AVCHO) WB as reference food Wholegrain and white pearled test meals (different barley cultivars) AC Parkhill (high amylose, low β-glucan) Celebrity (high amylose, medium β-glucan) CDC Fibar (low amylose, high β-glucan) | All 6 test meals vs. WB: ↓ GR CDC Fibar (wholegrain) vs. AC Parkhill (wholegrain): ↓ GR and GI CDC Fibar (pearled) vs. CDC Fibar (wholegrain): ↑ GI | NA |

| Lappi et al., 2013 [66] | Finland | RX 240 | Healthy subjects with self-reported gastrointestinal symptoms after ingestion of cereal foods, particularly rye bread 15 57.0 6M:9F 26.0 | Arabinoxylan Fructan β-Glucan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) WB (TDF: 3.8 g, 1.3 g total arabinoxylan, 0.8 g soluble arabinoxylan, 0.4 g fructan, 0.2 g β-glucan/Pr: 9.6 g/L: 6.1 g) White Wheat Rye Bread (WWR) (TDF: 16.4 g, 5.3 g total arabinoxylan, 1.7 g soluble arabinoxylan, 2.4 g fructan, 1.7 g β-glucan/Pr: 9.2 g/L: 1.0 g) WB fortified with bioprocessed rye bran (BRB) (TDF: 16.8 g, 8.3 g total arabinoxylan, 3.8 g soluble arabinoxylan, 1.2 g fructan, 0.8 g β-glucan/Pr: 15.8 g/L: 10.1 g) WB fortified with native rye bran (WWRB) (TDF: 19.1 g, 7.6 g total arabinoxylan, 1.5 g soluble arabinoxylan, 2.0 g fructan, 2.3 g β-glucan/Pr: 14.5 g/L: 9.7 g) + 40 g cucumber, 20 g milk-free margarine, and 3 dl water or 1.75 dl filtered coffee or black tea | ND in GR and iAUC between test meals | WWRB vs. WB, BRB, WWRB: ↓ InsR at 60 min ↓ Ins iAUC |

| Breen et al., 2013 [35] | Ireland | RX 270 | Subjects with T2DM and obesity 10 53.9 ± 5.5 6M:4F 35.1 ± 7.5 | NM | (50 g AVCHO) WB (TDF: 3.4 g/Pr: 10.8 g/L: 1.17 g) Whole-meal Soda Bread (WSB) (TDF: 7.4 g/Pr: 9.6 g/L: 2.2 g) WGB (TDF: 7.5 g/Pr: 12.9 g/L: 2.9 g) Pumpernickel rye Bread (PRB) (TDF: 19.2 g/Pr: 10.2 g/L: 3.9 g) | PRB vs. WGB: ↓ mean iAUC PRB vs. WB, WSB, WGB: ↓ peak Glu PRB vs. WB: ↓ 2-h PPG WSB, WGB, WB: 2 h postprandial hyperglycemia (>140 mg/dL) PRB, WSB vs. WB, WGB: ↓ peak time (55.5, 58.5 vs. 75.0, 72.0 min) | PRB vs. WB, WGB: ↓ iAUC ↓ peak Ins WSB, WGB, WB: 2 h postprandial hyperinsulinemia |

| Kristensen et al., 2013 [37] | Denmark | RX double-blind 420 | Young men 17 27.2 ± 2.2 18M 25.4 ± 2.2 | Flaxseed DF (70–80% water-soluble DF) | 4 iso-caloric meals 2 buns with cheese, butter, ham, and different flaxseed fractions C (TDF: 7 g/CHO: 147 g/Pr: 44 g/L: 49 g) Whole flaxseed (WF) (TDF: 12 g/CHO: 147 g/Pr: 44 g/L: 49 g) Low-dose mucilage (LM) (TDF: 12 g/CHO: 147 g/Pr: 44 g/L: 50 g) High-dose mucilage (HM) (TDF: 17 g/CHO: 147 g/Pr: 44 g/L: 49 g) | ND in PPG and AUC0–180 between test meals | HM vs. C: ↓ InsR at 30 min HM vs. WF: ↓ InsR at 30 and 180 min LM vs. C, WF: ↓ AUC0–180 HM vs. C, WF: ↓ AUC0–180 |

| Stringer et al., 2013 [52] | Canada | RX, single-blind 180 | Trial 1: Healthy subjects with HbA1c < 6% 11 37.3 ± 16.3 6M:6F 23.5 ± 3.4 Trial 2: Subjects with well-controlled T2DM with HbA1c < 7.5% 12 60.8 ± 6.7 5M:7F 32.4 ± 6.6 | NM | (50 g AVCHO) Rice crackers (TDF: 2.0 g/CHO: 51.8 g/Pr: 4.0 g/L: 8.1 g) Buckwheat crackers (TDF: 3.2 g/CHO: 53.1 g/Pr: 10.7 g/L: 10.6 g) | ND in PPG and AUC0–180 between test meals | NA |

| Hartvigsen et al., 2014 [53] | Denmark | RX 270 | Men and postmenopausal women with MetS 15 62.8 ± 4.2 7M:8F 31.1 ± 3.2 | Arabinoxylan (soluble DF) β-glucan (soluble DF) (PromOat) | (50 g AVCHO) WB (TDF: 2.9 g/Pr: 9.0 g/L: 2.3 g) Wheat bread with 13.3% of oat β-glucan (BG) (TDF: 13.4 g/Pr: 9.8 g/L: 2.5 g) Wheat bread with 24.4% of wheat arabinoxylan (AX) (TDF: 11.2 g/Pr: 19.4 g/L: 2.6 g) Rye bread with kernels (RK) (TDF: 12.2 g/Pr: 7.3 g/L: 7.3 g) | BG (GI = 84%), RK (GI = 77%) vs. WB (GI = 100%): ↓ GI BG, RK vs. WB: ↓ Glu iAUC0–120 AX, BG, RK vs. WB: ↓ peak Glu | AX, WB, BG vs. RK: ↑ Ins iAUC0–120 AX vs. BG: ↑ Ins iAUC0–120 |

| Moazzami et al., 2014 [63] | Sweden | RX 180 | Healthy postmenopausal women 19 61.0 ± 4.8 19F 26.0 ± 2.5 | Soluble and insoluble DF | (50 g AVCHO) Sourdough containing both yeast and lactobacilli was used in all RBs Refined wheat bread (RWB) as reference bread (TDF: 2.7 g, 1.5 g insoluble, 1.2 g soluble/Pr: 9.0 g/L: 5.2 g) Refined rye bread (RRB) (TDF: 6.1 g, 3.1 g insoluble DF, 3.0 g soluble/Pr: 4.9 g/L: 3.4 g) Whole-meal rye bread (WRB) (TDF: 15.2 g, 10.9 g insoluble and 4.3 g soluble/Pr: 11.1 g/L: 7.8 g) + 40 g cucumber and 3 dl noncaloric orange drink | ND in PPG responses between breads at 30, 45, 60, 180 min WRB vs. RWB: ↑ GR at 90 min ND in GR between RRB and the other bread samples | NA |

| Poquette et al., 2014 [67] | USA | RX 180 | Healthy subjects 10 25.1 ± 4.0 10M 24.2 ± 2.8 | RS | (50 g AVCHO) Whole-Wheat Flour Muffin (WWF) (Pr: 7.8%/L: 16.0%) Wholegrain Sorghum Muffin (WGS) (Pr: 5.2%/L: 18.5%/↑ RS content) | WGS vs. WGW: ↓ GR at 45, 60, 75, 90, 120 min ↓ 26% Glu iAUC0–120 ND in GR at 180 min between test meals | WGS vs. WGW: ↓ InsR at 15, 30,45, 60, 75, 90 min ↓ 55% Ins iAUC0–120 ND in InsR at 180 min between test meals |

| Ames et al., 2015 [32] | Canada | RX, double-blind 180 | Healthy subjects 12 27.0 7M:5F 23.8 | β-Glucan (soluble DF) Insoluble DF RS | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food Barley tortilla made from: Straight-grade flour (SGF)—low β-glucan/low soluble DF (TDF: 10.29 g, 7.55 g insoluble, 4.5 g β-glucan, 0.45 g RS/Pr: 13.67 g) Wholegrain flour (WGF)—medium β-glucan/low insoluble DF (TDF: 14.28 g, 7.43 g insoluble, 7.77 g β-glucan, 0.42 g RS/Pr: 13.28 g) Bran flour with β-glucan/low insoluble DF (BF-BG) (TDF: 18.03 g, 7.47 g insoluble, 11.55 g β-glucan, 0.85 g RS/Pr: 14.71 g) Bran flour with high insoluble DF/medium β-glucan (BF-IDF) (TDF: 26.87 g, 19.64 g insoluble, 8.56 g β-glucan, 0.68 g RS/Pr: 21.50 g) High-amylose dusted flour fractions (HA-DFF)—medium β-glucan/low insoluble DF (TDF: 14.14 g, 8.29 g insoluble, 6.27 g β-glucan, 1.41 g RS/Pr: 12.08 g) | BF-BG (GI = 22.7) vs. SGF (GI = 51.8), WGF (GI = 57.3): ↓ 56–60% GI ND in GI between WGF and HA-DFF (GI = 39.2) and between WGF and BF-IDF (GI = 40.9) BF-BG vs. SGF: ↓ 61% Glu iAUC BF-BG vs. SGF, WGF: ↓ 3.9–5.1 times change from baseline at 30 min ND in Glu iAUC or %change from baseline at 30 min between WGF and HA-DFF or between WGF and BF-IDF | HA-DFF, BF-BG vs. SGF: Returned to baseline at 120 vs. 180 min BF-BG vs. WGF: ↓ 39% Ins iAUC WGF vs. SGF: ↓ 33% Ins iAUC SGF vs. WGF, BF-BG: ↑ 64–176% change from baseline at 30 min ND in Ins iAUC between WGF and BF-IDF BF-IDF vs. WGF: ↑ Ins %change from baseline at 30 min ND in iAUC between WGF and HA-DFF |

| Johansson et al., 2015 [54] | Sweden | RX 230 | Healthy subjects 23 60.1 ± 12.1 7M:16F 23.8 ± 3.4 | Arabinoxylan Arabinogalactan β-Glucan Cellulose and RS Fructan Klason lignin | Unfermented wholegrain rye crispbread (uRCB) (TDF: 20.5 g–8.8 g arabinoxylan, 0.1 g arabinogalactan, 2.5 g β-glucan, 2.7 g cellulose and RS, 4.0 g fructan, 1.3 g Klason lignin) Yeast-fermented wholegrain rye crispbread (RCB) (TDF: 18.3 g–8.6 g arabinoxylan, 0.2 g arabinogalactan, 2.1 g β-glucan, 2.5 g cellulose and RS, 2.6 g fructan, 1.3 g Klason lignin) Yeast-fermented refined wheat crispbread (WCB) (TDF: 6.0 g–2.5 g arabinoxylan, 0.2 g arabinogalactan, 0.3 g β-glucan, 1.4 g cellulose and RS, 0.4 g fructan, 0.5 g Klason lignin) + margarine and cheese, a glass of orange juice, and a cup of coffee or tea | ND in PPG between test meals | uRCB, RCB vs. WCB: ↓ InsR at 65 and 95 min uRCB vs. RCB, WCB: ↓ 13% and 17% Ins secretion, ↓ 12% and 21% InsR RCB vs. WCB: ND in AUC0–230 RCB vs. WCB: ↓ 10% InsR |

| Soong et al., 2015 [57] | Singapore | RX, non-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 12 26.2 ± 5.3 4M:8F 20.2 ± 1.7 | Oat and barley β-glucan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food Wheat Muffins (WM) (TDF: 3.7 g/CHO: 91.0 g/Pr: 14.1 g/L: 1.5 g) Rice Muffins (RM) (TDF: 3.2 g/CHO: 99.2 g/Pr: 6.4 g/L: 1.6 g) Corn Muffins (CM) (TDF: 17.7 g/CHO: 79.5 g/Pr: 8.8 g/L: 4.5 g) Oat Muffins (OM) (TDF: 12.8 g/CHO: 70.4 g/Pr: 22.4 g/L:9.6 g) Barley Muffins (BM) (TDF: 21.4 g/CHO: 76.8 g/Pr: 12.8 g/L: 0 g) | WM, CM, BM vs. RM, OM: peak Glu at 30 vs. 45 min WM, RM, CM vs. BM: ↑ peak Glu WM (GI = 74), RM (GI = 79), CM (GI = 74) vs. BM (GI = 55): ↓ 120 min period GR OM (GI = 53): ↓ iAUC at 45 min OM: rapid ↓ GR at 45 min WM, RM, CM, BM: gradual ↓ GR WM, CM, OM, BM vs. RM: Glu above baseline at 120 min | NA |

| Robert et al., 2016 [46] | Malaysia | RX 120 | Healthy individuals 10 21–48 5M:5F 20.0–30.2 | Galacto-mannan from fenugreek seed (soluble, viscous DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food Bun C (CB) (TDF: 3.0 g/Pr: 9.4 g/L: 5.0 g) 10% Fenugreek Bun (FB) (TDF: 12.0 g/Pr: 15.0 g/L: 5.5 g) Flatbread C (CF) (TDF: 3.0 g/Pr: 9.0 g/L: 1.4 g) 10% Fenugreek Flatbread (FF) (TDF: 6.0 g/Pr: 10.4 g/L: 3.0 g) | FB (GI = 51) vs. CB (GI = 82): ↓ 39.2% Glu AUC (GR) ↓ 38% GI FF (GI = 43) vs. CF (GI = 63): ↓ 30.4% Glu AUC (GR) ↓ 32% GI | NA |

| Mohan et al., 2016 [49] | India | RX 120 | Healthy volunteers Study 1 (2013): 25 27.9 ± 0.9 13M:12F 22.3 ± 0.5 Study 2 (2014): 15 26.7 ± 1.0 7M:8F 20.6 ± 0.4 | RS | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food WR (Per 100 g of uncooked rice—TDF: 1.58 g, 0.6 g RS/AVCHO: 77.1 g/Pr: 9.4 g/L: 0.8 g) High-fiber WR (HFWR) (Per 100 g of uncooked rice—TDF: 8.0 g, 3.9 g RS/AVCHO: 75.1 g/Pr: 8.0 g/L: 0.3 g) | Mean values from the 2 studies HFWR (GI = 61.3) vs. WR (GI = 79.2): ↓ 23% GI, and iAUC | NA |

| Stamataki et al., 2016 [55] | Greece | RX 180 | Healthy subjects 11 22.4 ± 1.6 6M:5F 23.2 ± 2.8 | Inulin (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food Biscuit samples: oat flakes (40%), whole-wheat flour (60%) Oat biscuits (OB) (TDF: 5.1 g/Pr: 6.8 gr/L: 15.3 g) Oat biscuits with 4% inulin (OBIN) (TDF: 5.4 g, 3.3 g inulin/Pr: 8.0 g/L: 14.0 g) | OB vs. OBIN: ↓ peak Glu at 45 min OB, OBIN vs. GS: ↓ iAUC ND in iAUC between OB and OBIN OBIN (GI = 45.68) vs. OB (GI = 32.82): ↑ GI | OBIN vs. OB: ↑ Ins at 45, 60 min ND in iAUC between test meals OBIN vs. OB: Peak Ins at 45 min vs. 30 min ND in peak Ins between test meals |

| Boers et al., 2017 [59] | India | RX, double-blind 180 | Healthy South-Asian subjects 50 29.16 ± 0.71 30M:26F 20.77 ± 0.20 | β-Glucan (soluble DF) | 100% wheat-flour-based flatbread as C (TDF: 8.0 g/AVCHO: 65.0 g) Flatbread samples 2% guar gum (80 g HFF + 15 g CPF + 3 g BF) (TDF: 16.0 g/AVCHO: 56.0 g) 3% guar gum (77 g HFF + 15 g CPF + 5 g BF) (TDF: 17.0 g/AVCHO: 54.0 g) 4% guar gum (81 g HFF + 15 g CPF) (TDF: 18.0 g/AVCHO: 53.0 g) | 3, 4% guar gum vs. C: ↓ iAUC0–120 | 2, 3, 4% guar gum vs. C: ↓ Ins iAUC0–120 |

| Khan et al., 2017 [65] | Australia | RX 120 | Healthy subjects 20 21.5 ± 1.15 10M:10F 17.97 ± 3.08 | NM | (50 g AVCHO) C cookies (CC) made with plain wheat flour (TDF: 0.58 g/Pr: 7.88 g/L: 1.02 g) Cookies containing 3% bay leaf powder (B3) (TDF: 0.99 g/Pr: 8.07 g/L: 1.13 g) Cookies containing 6% bay leaf powder (B6) (TDF: 1.4 g/Pr: 8.27 g/L: 1.24 g) | B6 vs. CC: ↓ GR at 30 and 45 min ND in iAUC0–120 between test meals | NA |

| Stewart and Zimmer, 2017 [41] | USA | RX, double-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 28 42.8 ± 18.5 14M:14F 24.7 ± 3.3 | VERSAFIBETM 1490 RS type 4 | C cookie (CC) (TDF: 0.55 g/AVCHO: 36.28 g/Pr: 5.36 g/L: 3.99 g) Fiber cookie (FC) (TDF: 24.13 g/AVCHO: 12.71 g/Pr: 4.92 g/L: 3.92 g) | FC vs. CC: ↓ intravenous Glu at 45 min ↓ capillary Glu at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 min ↓ 44% intravenous and ↓ 48% capillary Glu iAUC0–120 ↓ 8% intravenous and ↓ 9% capillary Cmax0–120 | FC vs. CC: ↓ intravenous Ins at 45, 60, 90, 120 min ↓ 46% intravenous Ins iAUC0–120 and ↓ 23% Cmax0–120 |

| Zamaratskaia et al., 2017 [58] | Sweden | RX, single-blind 250 | Healthy subjects 23 30.0 ± 11.0 13M:11F 23.0 ± 5.0 | Arabinoxylan Arabinogalactan β-Glucan Cellulose and RS Fructan Klason lignin | Refined wheat crispbread as C Yeast-fermented refined wheat crispbread (TDF: 6.0–2.5% arabinoxylan, 0.2% arabinogalactan, 0.3% β-glucan, 1.4% cellulose, and RS, 0.4% fructan, 0.5% Klason lignin) (TDF: 2.9 g/CHO: 35.0 g/Pr: 6.5 g/L: 4.1 g) Unfermented rye crispbread (TDF: 20.5–8.8% arabinoxylan, 0.1% arabinogalactan, 2.5% β-glucan, 2.7% cellulose and resistant starch, 4.0% fructan, 1.3% Klason lignin) (TDF: 11.7 g/CHO: 35.4 g/Pr: 6.0 g/L: 0.9 g) Sourdough-fermented rye crispbread (TDF: 17.5–8.2% arabinoxylan, 0.2% arabinogalactan, 2.1% β-glucan, 2.7% cellulose, and resistant starch, 1.7% fructan, 1.5% Klason lignin) (TDF: 9.5 g/CHO: 36.2 g/Pr: 5.1 g/L: 1.1 g) + coffee/tea (150 mL), margarine, cheese, and juice (150 mL) | ND in PPG responses between test meals | Unfermented rye vs. sourdough-fermented rye, C: ↓ Ins AUC0–230 Sourdough-fermented rye vs. C: ND in Ins AUC0–230 ND in PPI responses between test meals |

| Stewart and Zimmer, 2018 [40] | USA | RX double-blind 120 | Healthy adults 28 41.1 ± 17.2 14M:14F 24.5 ± 3.4 | VERSAFIBETM 2470 Resistant Starch (RS) type 4 with 70% DF | C Muffin Top (CMT) (TDF: 0.9 g/CHO: 29.0 g/AVCHO: 28.1/Pr: 4.0 g/L: 4.3 g) Fiber Muffin Top (FMT) (TDF: 11.6 g/CHO: 29.0 g/AVCHO: 17.4/Pr: 4.0 g/L: 4.3 g) | FMT vs. CMT: ↓ venous blood Glu at 15 and 30 min ↓ 33% venous Glu iAUC0–120 ↓ 8% venous Glu Cmax 0–120 ↓ capillary blood Glu at 30 min | FMT vs. CMT: ↓ venus Ins at 30, 45, 60 min ↓ Ins iAUC0–120 ND in venous Ins Cmax 0–120 |

| Akhtar et al., 2019 [34] | Pakistan | RX 120 | Normoglycemic healthy young adults 24 M: 21.1 ± 1.2/F: 23.8 ± 2.6 12M:12F M: 22.5 ± 1.7/F: 21.0 ± 1.7 | NM | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food All-purpose wheat flour chapatti (APFC)-100% wheat flour (TDF: 3.60 g/Pr: 5.05 g/L: 0.81 g) Vegetable-powder-supplemented chapatti (VPSC)-20% vegetable powder (TDF: 6.72 g/Pr: 8.62 g/L: 0.90 g) Bean-powder-supplemented chapatti (BPSC)-25% bean powder (TDF: 5.33 g/Pr: 8.92 g/L: 1.14 g) + fried egg cooked with sunflower oil | BPSC (GI = 44) and VPSC (GI = 46) vs. APFC (GI = 82): ↓ 46% and 44% GI BPSC and VPSC vs. APFC: ↓ GR at 15, 30, 45 min ↓ 44% and 49% iAUC0–120 | VPSC and BPSC vs. APFC: ↓ InsR at 60 min ↓ amplitude of PPI |

| Belobrajdic et al., 2019 [61] | Australia | RX 180 | Healthy subjects 19 30.0 ± 3.0 5M:15F 23.0 ± 0.7 | RS (fermentable DF) | Glu as reference food Per 100 g bread: High-amylose wheat refined bread (HAW-R) (TDF: 5.5 g, 4.7 g RS/Pr: 13.1 g/L: 2.8 g) High-amylose wheat whole-meal bread (HAW-W) (TDF: 10.4 g, 3.2 g RS/Pr: 15.2 g/L: 3.6 g) Low-amylose wheat refined bread (LAW-R) (TDF: 3.3 g, 0.4 g RS/Pr: 10.8 g/L: 3.4 g) Low-amylose wheat whole-meal bread (LAW-W) (TDF: 8.2 g, 0.3 g RS/Pr: 12.1 g/L: 3.7 g) | HAW vs. LAW breads: ↓ 39% Glu iAUC ↓ 33% Glu Cmax | HAW vs. LAW breads: ↓ 24% Ins iAUC HAW-W vs. LAW-R: ↓ InsR at 60 and 120 min HAW-R vs. LAW-R: ↓ InsR at 120 min |

| Matsuoka et al., 2020 [60] | Japan | RX, double-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 23 22.8 ± 1.4 7M:16F 21.0 ± 2.6 | β-Glucan (soluble DF) | (50 g AVCHO) Wheat flour bread (WFB) (TDF: 1.8 g, 0.19 g β-glucan/Pr: 8.5 g/L: 4.9 g) Barley flour bread (BFB) (TDF: 3.0 g, 2.5 g β-glucan/Pr: 16.8 g/L: 6.3 g) +180 mL lactose-free milk | BFB vs. WFB: ↓ peak Glu | NA |

| Yoshimoto et al., 2020 [62] | Japan | RX, double-blind 120 | Healthy subjects 12 37.8 ± 9.5 8M:4F 22.9 ± 3.5 | Legumes (insoluble DF) | WB as reference food Legume-based noodle samples: Dehulled yellow pea noodles (YP) (TDF: 5.3 g/%RAG: 8.34/CHO: 23.1 g/Pr: 10.1 g/L: 1.0 g) Unshelled yellow pea noodles (YP-U) (TDF: 7.8 g/%RAG: 8.20/CHO: 20.0 g/Pr: 8.7 g/L: 1.0 g) | YP, YP-U vs. WΒ: ↓ GR at 45, 60, 90 min YP vs. YP-U: ↓ GR at 45 min ND in iAUC between YP and YP-U | NA |

| Papakonstantinou et al., 2022 [72] | Greece | RX, single-blind 120 | Healthy individuals 14 25.0 ± 1.0 4M:10F 23.0 ± 1.0 | Soluble DF | (50 g AVCHO) Glu as reference food WB as reference food Spaghetti made with hard WDS flour (S) (TDF: 1.8 g/CHO: 72.0 g/Pr: 12.0 g/L: 1.5 g) Wholegrain spaghetti made with wholegrain hard wheat flour (WS) (TDF: 7.0 g/CHO: 67.6 g/Pr: 12.8 g/L: 2.1 g) Spaghetti high in soluble fiber and low in CHO made with hard WDS flour, rice bran, oat fibers, and flaxseed flour (HFLowCS) (TDF: 21.1 g/CHO: 47.4 g/Pr: 14.9 g/L: 4.6 g) | S, WS, HFLowCS vs. Glu, WB: ↓ GR at 15, 30, 45, 60 min with ND between them ↓ peak Glu S, WS vs. Glu: ↓ GR at 90 min WS vs. Glu: ↑ GR at 120 min S vs. WB: ↓ GR at 30 and 120 min S, WS, HFLowCS: ↓ GR at 45, 60, 90 min S vs. WS, HFLowCS: ↓ peak Glu S, WS, HFLowCS vs. Glu: ↓ Glu iAUC0–120 ND in Glu iAUC0–120 between the three types of spaghetti S vs. WB: ↓ Glu iAUC0–120 | ND in salivary Ins between test meals and Glu or WB ND in iAUC0–120, peak Ins, and time to peak between test meals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsitsou, S.; Athanasaki, C.; Dimitriadis, G.; Papakonstantinou, E. Acute Effects of Dietary Fiber in Starchy Foods on Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Crossover Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102383

Tsitsou S, Athanasaki C, Dimitriadis G, Papakonstantinou E. Acute Effects of Dietary Fiber in Starchy Foods on Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Crossover Trials. Nutrients. 2023; 15(10):2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102383

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsitsou, Sofia, Christina Athanasaki, George Dimitriadis, and Emilia Papakonstantinou. 2023. "Acute Effects of Dietary Fiber in Starchy Foods on Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Crossover Trials" Nutrients 15, no. 10: 2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102383

APA StyleTsitsou, S., Athanasaki, C., Dimitriadis, G., & Papakonstantinou, E. (2023). Acute Effects of Dietary Fiber in Starchy Foods on Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Crossover Trials. Nutrients, 15(10), 2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102383