Caffeine Intake and Its Sex-Specific Association with General Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among General Population Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

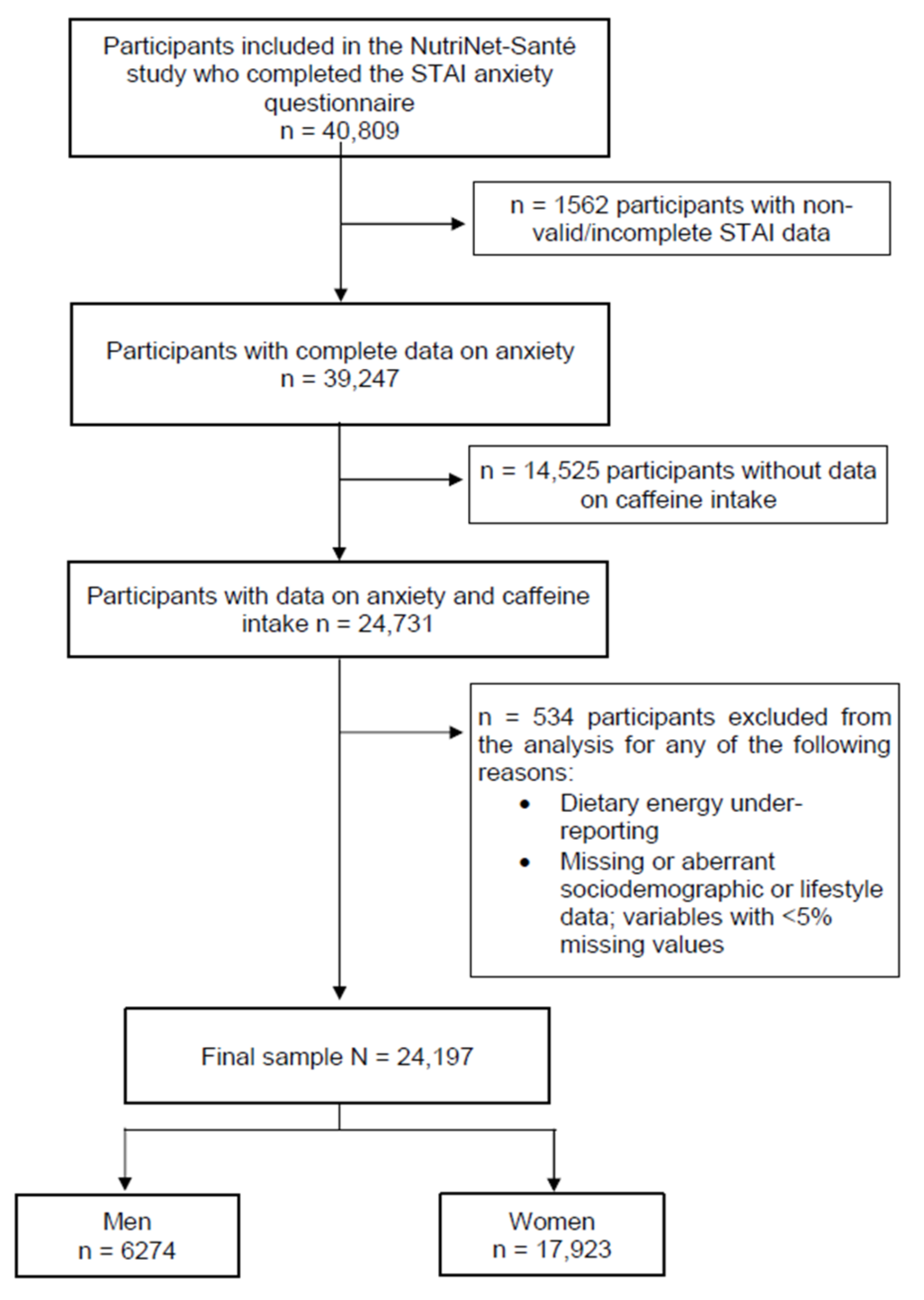

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Assessment of Caffeine and Dietary Intake

2.3. Trait Anxiety

2.4. Assessment of Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Description of Caffeine Intake

3.3. Association between Caffeine Intake and Trait Anxiety

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.L.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Herrera, A.M.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K. (Ed.) Anxiety Disorders, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 1191. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.; Mercer, J.G. Diet-Regulated Anxiety. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 701967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörkl, S.; Wagner-Skacel, J.; Lahousen, T.; Lackner, S.; Holasek, S.J.; Bengesser, S.A.; Painold, A.; Holl, A.K.; Reininghaus, E. The Role of Nutrition and the Gut-Brain Axis in Psychiatry: A Review of the Literature. Neuro Psychobiol. 2020, 79, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, O.; Keshteli, A.H.; Afshar, H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Adibi, P. Adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern is inversely associated with depression, anxiety and psychological distress. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Pasco, J.A.; Mykletun, A.; Williams, L.J.; Hodge, A.M.; O’Reilly, S.L.; Nicholson, G.C.; Kotowicz, M.A.; Berk, M. Association of Western and Traditional Diets With Depression and Anxiety in Women. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haynes, J.C.; Farrell, M.; Singleton, N.; Meltzer, H.; Araya, R.; Lewis, G.; Wiles, N.J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for anxiety and depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 187, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lara, D.R. Caffeine, Mental Health, and Psychiatric Disorders. J. Alzheimer Dis. 2010, 20, S239–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, C.F.; Kennedy, D.; Wesnes, K.; Scholey, A. Cognitive and mood improvements of caffeine in habitual consumers and habitual non-consumers of caffeine. Psychopharmacology 2005, 179, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Sturgess, W.; Gallagher, J. Effects of a low dose of caffeine given in different drinks on mood and performance. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 1999, 14, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Graniel, I.; the PREDIMED-Plus Investigators; Babio, N.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Toledo, E.; Camacho-Barcia, L.; Corella, D.; Castañer-Niño, O.; Romaguera, D.; Vioque, J.; et al. Association between coffee consumption and total dietary caffeine intake with cognitive functioning: Cross-sectional assessment in an elderly Mediterranean population. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2381–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Micek, A.; Castellano, S.; Pajak, A.; Galvano, F. Coffee, tea, caffeine and risk of depression: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Shen, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D. Coffee and caffeine consumption and depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellana, F.; De Nucci, S.; De Pergola, G.; Di Chito, M.; Lisco, G.; Triggiani, V.; Sardone, R.; Zupo, R. Trends in Coffee and Tea Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2021, 10, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.; Sosa-Napolskij, M.; Lobo, G.; Silva, I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Portuguese population: Consumption of alcohol, stimulant drinks, illegal substances, and pharmaceuticals. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, A.V.; Sabatini, S. Changes in energy drink consumption during the COVID-19 quarantine. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 45, 516–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hercberg, S.; Castetbon, K.; Czernichow, S.; Malon, A.; Mejean, C.; Kesse, E.; Touvier, M.; Galan, P. The Nutrinet-Santé Study: A web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvier, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Méjean, C.; Pollet, C.; Malon, A.; Castetbon, K.; Hercberg, S. Comparison between an interactive web-based self-administered 24 h dietary record and an interview by a dietitian for large-scale epidemiological studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullec, N.L.; Deheeger, M.P.P. Validation du manuel photos utilisées pour l’enquête alimentaire de l’étude SU.VI.MAX Validation of the photo manual used for the food survey of the SU.VI.MAX study. Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique 1996, 31, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lassale, C.; Péneau, S.; Touvier, M.; Julia, C.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Validity of Web-Based Self-Reported Weight and Height: Results of the Nutrinet-Santé Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vergnaud, A.-C.; Touvier, M.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Pollet, C.; Malon, A.; Castetbon, K.; Hercberg, S. Agreement between web-based and paper versions of a socio-demographic questionnaire in the NutriNet-Santé study. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lassale, C.; Castetbon, K.; Laporte, F.; Deschamps, V.; Vernay, M.; Camilleri, G.M.; Faure, P.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Correlations between Fruit, Vegetables, Fish, Vitamins, and Fatty Acids Estimated by Web-Based Nonconsecutive Dietary Records and Respective Biomarkers of Nutritional Status. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 427–438.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etude Nutrinet. Table de composition des aliments, étude NutriNet-Santé Food composition table, NutriNet-Santé study. Económica 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Black, A.E. Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake:basal metabolic rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Langevin, V.; Boini, S.; François, M.; Riou, A. Inventaire d’anxiété état-trait forme Y State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y). Ref. Sante Trav. 2012, 131, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J.A.; Power, K.G.; Durham, R.C. The relationship between trait vulnerability and anxiety and depressive diagnoses at long-term follow-up of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortamais, M.; Abdennour, M.; Bergua, V.; Tzourio, C.; Berr, C.; Gabelle, A.; Akbaraly, T.N. Anxiety and 10-Year Risk of Incident Dementia—An Association Shaped by Depressive Symptoms: Results of the Prospective Three-City Study. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lago-Méndez, L.; Diniz-Freitas, M.; Senra-Rivera, C.; Seoane-Pesqueira, G.; Gándara-Rey, J.-M.; Garcia-Garcia, A. Dental Anxiety Before Removal of a Third Molar and Association with General Trait Anxiety. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, F.-X.; Berjot, S.; Deschamps, F. Psychometric properties of the French versions of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2012, 25, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, V.A.; Fezeu, L.K.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P. Obesity and Migraine: Effect Modification by Gender and Perceived Stress. Neuroepidemiology 2018, 51, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kose, J.; Cheung, A.; Fezeu, L.; Péneau, S.; Debras, C.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Andreeva, V. A Comparison of Sugar Intake between Individuals with High and Low Trait Anxiety: Results from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treur, J.L.; Taylor, A.E.; Ware, J.J.; McMahon, G.; Hottenga, J.-J.; Baselmans, B.M.L.; Willemsen, G.; Boomsma, D.I.; Munafo, M.; Vink, J.M. Associations between smoking and caffeine consumption in two European cohorts. Addiction 2016, 111, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Altemus, M.; Sarvaiya, N.; Epperson, C.N. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front. Neuroendocr. 2014, 35, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammer, J.H.; Parent, M.C.; Spiker, D.A.; World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 65, p. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Hong, K.; Bergquist, K.; Sinha, R. Gender Differences in Response to Emotional Stress: An Assessment Across Subjective, Behavioral, and Physiological Domains and Relations to Alcohol Craving. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2008, 32, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Urbán, R.; Király, O.; Griffiths, M.D.; Rogers, P.J.; Demetrovics, Z. Why Do You Drink Caffeine? The Development of the Motives for Caffeine Consumption Questionnaire (MCCQ) and Its Relationship with Gender, Age and the Types of Caffeinated Beverages. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 16, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Botella, P. Coffee increases state anxiety in males but not in females. Hum. Psycho Pharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2003, 18, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Tharion, W.J.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Speckman, K.L.; Tulley, R. Effects of caffeine, sleep loss, and stress on cognitive performance and mood during U.S. Navy SEAL training. Psycho Pharmacol. 2002, 164, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.J.; Hohoff, C.; Heatherley, S.V.; Mullings, E.L.; Maxfield, P.J.; Evershed, R.P.; Deckert, J.; Nutt, D.J. Association of the Anxiogenic and Alerting Effects of Caffeine with ADORA2A and ADORA1 Polymorphisms and Habitual Level of Caffeine Consumption. Neuro Psychopharmacol. 2010, 35, 1973–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviola, F.; Pappaianni, E.; Monti, A.; Grecucci, A.; Jovicich, J.; De Pisapia, N. Trait and state anxiety are mapped differently in the human brain. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.N. Drugs which induce anxiety: Caffeine. N. Z. J. Psychol. 1996, 25, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Greden, J.F.; Fontaine, P.; Lubetsky, M.; Chamberlin, K. Anxiety and depression associated with caffeinism among psychiatric inpatients. Am. J. Psychiatry 1978, 135, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSES—French Agency for Food Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety. AVIS De L’agence Nationale De Sécurité Sanitaire De L’alimentation, De L’environnement Et Du Travail Relatif À L’évaluation Des Risques Liés À La Consommation De Boissons Dites « Énergisantes »; Avis l’Anses Saisine N° 2012-SA-0212; Anses Édition: Maisons-Alfort, France, 2013; Volume 124. [Google Scholar]

- Balhara, Y.S.; Verma, R.; Gupta, C. Gender differences in stress response: Role of developmental and biological determinants. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2012, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rincón-Cortés, M.; Herman, J.P.; Lupien, S.; Maguire, J.; Shansky, R.M. Stress: Influence of sex, reproductive status and gender. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 10, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.; Ahluwalia, A.; Potenza, M.N.; Sinha, R. Gender differences in neural correlates of stress-induced anxiety. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjørngaard, J.H.; Nordestgaard, A.T.; Taylor, A.E.; Treur, J.L.; Gabrielsen, M.E.; Munafò, M.R.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Åsvold, B.O.; Romundstad, P.; Davey Smith, G. Heavier smoking increases coffee consumption: Findings from a Mendelian randomization analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1958–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nehlig, A.; Daval, J.-L.; DeBry, G. Caffeine and the central nervous system: Mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects. Brain Res. Rev. 1992, 17, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basurto-Islas, G.; Blanchard, J.; Tung, Y.C.; Fernandez, J.R.; Voronkov, M.; Stock, M.; Zhang, S.; Stock, J.B.; Iqbal, K. Therapeutic benefits of a component of coffee in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 2701–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Godos, J.; Pluchinotta, F.R.; Marventano, S.; Buscemi, S.; Li Volti, G.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Coffee components and cardiovascular risk: Beneficial and detrimental effects. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J. Psychological effects of dietary components of tea: Caffeine and L-theanine. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, V.A.; Salanave, B.; Castetbon, K.; Deschamps, V.; Vernay, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Hercberg, S. Comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the large NutriNet-Santé e-cohort with French Census data: The issue of volunteer bias revisited. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2015, 69, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Full Sample | Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 24,197 | T1 n = 2092 | T2 n = 2091 | T3 n = 2091 | p Value a | T1 n = 5975 | T2 n = 5974 | T3 n = 5974 | p Value b | |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day | 220.6 ± 165 | 76.0 ± 47.7 | 218.8 ± 38.5 | 436.8 ± 157.8 | <0.01 | 62.3 ± 36.8 | 186.4 ± 35.8 | 388.6 ± 139.5 | <0.01 |

| High trait anxiety † | 23.4 (489) | 20.7 (433) | 20.4 (427) | 0.03 | 23.8 (1419) | 24.1 (1438) | 24.4 (1459) | 0.69 | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 53.7 ± 13.9 | 57.1 ± 14.8 | 60.8 ± 12.4 | 59.1 ± 12.0 | <0.01 | 47.8 ± 14.7 | 53.5 ± 13.3 | 54.3 ± 11.9 | <0.01 |

| Age category | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| <40 years | 20.7 (5019) | 17.7 (370) | 8.8 (184) | 8.9 (185) | 36.9 (2204) | 19.9 (1191) | 14.8 (885) | ||

| 40–60 years | 39.1 (9454) | 28.4 (595) | 27.7 (579) | 34.9 (730) | 36.5 (2179) | 42.1 (2515) | 47.8 (2856) | ||

| >60 years | 40.2 (9724) | 53.9 (1127) | 63.5 (1328) | 56.2 (1176) | 26.6 (1592) | 38.0 (2268) | 37.4 (2233) | ||

| Educational level | 0.51 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Less than high school | 13.9 (3372) | 16.3 (340) | 18.4 (384) | 18.4 (386) | 11.5 (686) | 13.7 (818) | 12.7 (758) | ||

| High school or equivalent | 16.8 (4058) | 18.6 (389) | 17.4 (364) | 17.4 (364) | 16.0 (955) | 16.6 (992) | 16.6 (994) | ||

| College, undergraduate degree | 27.9 (6746) | 22.9 (479) | 21.9 (458) | 22.6 (472) | 30.9 (1843) | 29.2 (1746) | 29.3 (1748) | ||

| Graduate degree | 36.3 (8788) | 40.0 (837) | 39.4 (825) | 39.2 (819) | 36.7 (2194) | 34.1 (2,037) | 34.8 (2076) | ||

| Not reported | 5.10 (1233) | 2.2 (47) | 2.9 (60) | 2.4 (50) | 5.0 (297) | 6.4 (381) | 6.7 (398) | ||

| Socio-professional category | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Homemaker/disabled/unemployed/student | 8.30 (2016) | 4.3 (91) | 2.2 (46) | 3.4 (70) | 11.5 (685) | 9.3 (555) | 9.5 (569) | ||

| Manual/office work/administrative staff | 30.5 (7389) | 20.8 (436) | 14.5 (304) | 18.6 (389) | 40.0 (2390) | 32.1 (1920) | 32.6 (1950) | ||

| Professional/executive staff | 23.1 (5578) | 22.7 (475) | 21.8 (4555) | 24.5 (513) | 23.4 (1398) | 22.7 (1357) | 23.1 (1380) | ||

| Retired | 38.10 (9214) | 52.1 (1090) | 61.5 (1286) | 53.5 (1119) | 25.1 (1502) | 35.9 (2142) | 34.7 (2075) | ||

| Marital status | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Living alone (single, divorced, widowed) | 23.4 (5674) | 20.5 (428) | 14.8 (310) | 14.9 (311) | 24.6 (1470) | 24.6 (1472) | 28.2 (1683) | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 76.6 (18,523) | 79.5 (1664) | 85.2 (1781) | 85.1 (1780) | 75.4 (4505) | 75.4 (4502) | 71.8 (4291) | ||

| Physical activity * | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Low | 36.8 (8906) | 44.6 (932) | 48.6 (1,107) | 45.2 (944) | 30.4 (1814) | 34.5 (2058) | 35.8 (2141) | ||

| Moderate | 41.3 (9986) | 34.9 (730) | 35.5 (742) | 36.1 (755) | 43.9 (2620) | 43.3 (2588) | 42.7 (2551) | ||

| High | 21.9 (5305) | 20.5 (430) | 15.9 (332) | 18.7 (392) | 25.8 (1541) | 22.2 (1328) | 21.5 (1282) | ||

| Smoking status | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Never smoker | 51.0 (12,351) | 52.7 (1103) | 39.3 (821) | 33.4 (699) | 66.1 (3949) | 52.6 (3142) | 44.1 (2637) | ||

| Former smoker | 39.4 (9519) | 41.9 (877) | 53.0 (1110) | 54.4 (1138) | 27.3 (1629) | 38.0 (2267) | 41.8 (2498) | ||

| Current smoker | 9.6 (2327) | 5.4 (112) | 7.7 (160) | 12.2 (254) | 6.6 (397) | 9.5 (565) | 14.0 (839) | ||

| Body Mass Index (BMI), kg/m2 | 23.8 ± 4.1 | 24.5 ± 3.5 | 25.0 ± 3.5 | 25.4 ± 3.6 | <0.01 | 23.1 ± 4.2 | 23.4 ± 4.2 | 23.5 ± 4.3 | <0.01 |

| BMI category | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 4.6 (1123) | 1.7 (36) | 0.9 (19) | 0.6 (13) | 6.7 (398) | 5.7 (338) | 5.3 (319) | ||

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 64.4 (15,588) | 59.7 (1250) | 56.1 (1173) | 50.1 (1048) | 68.8 (4108) | 67.9 (4056) | 66.2 (3953) | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 23.6 (5699) | 32.3 (675) | 35.7 (746) | 39.8 (33) | 17.5 (1048) | 19.3 (1154) | 20.8 (1243) | ||

| Obese (≥30) | 7.4 (1787) | 6.3 (131) | 7.3 (153) | 9.4 (197 | 7.0 (421) | 7.1 (426) | 7.7 (459) | ||

| Total energy intake, kcal/d | 1910.8 ± 440.4 | 2223.1 ± 452.5 | 2286.1 ± 454.0 | 2,324.3 ± 463.3 | <0.01 | 1759.8 ± 356.5 | 1772.5 ± 344.6 | 1814.8 ± 355.7 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol consumption, g ethanol/d | 8.5 ± 11.6 | 12.4 ± 16.3 | 16.6 ± 16.0 | 16.8 ± 15.4 | <0.01 | 4.5 ± 7.4 | 6.6 ± 8.3 | 7.5 ± 9.4 | <0.01 |

| Number of 24-h dietary records | 8.2 ± 3.8 | 8.5 ± 3.7 | 9.0 ± 3.6 | 8.8 ± 3.7 | <0.01 | 7.5 ± 3.8 | 8.1 ± 3.7 | 8.3 ± 3.7 | <0.01 |

| Perceived stress score‡ | 13.5 ± 6.9 | 11.6 ± 6.3 | 11.2 ± 6.2 | 11.3 ± 6.5 | 0.21 | 14.3 ± 6.9 | 14.2 ± 6.8 | 14.2 ± 6.9 | 0.48 |

| Caffeine Sources | Total Sample | Men (n = 6274) | Women (n = 17,923) | p Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total caffeinated beverages | 385.0 ± 290.4 | 343.8 ± 259.7 | 399.5 ± 299.1 | <0.01 |

| Total coffee | 160.5 ± 179.9 | 188.3 ± 188.9 | 150.7 ± 175.6 | <0.01 |

| Caffeinated coffee | 152.2 ± 174.9 | 179.9 ± 185.3 | 142.5 ± 170.1 | <0.01 |

| Decaffeinated coffee | 8.2 ± 46.1 | 8.4 ± 47.9 | 8.2 ± 45.5 | 0.73 |

| Tea | 211.7 ± 280.5 | 143.0 ± 229.2 | 235.7 ± 292.6 | <0.01 |

| Other caffeinated beverages b | 12.9 ± 63.3 | 12.5 ± 53.4 | 13.0 ± 66.4 | 0.54 |

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 n = 2092 | T2 n = 2091 | T3 n = 2091 | T1 n = 5975 | T2 n = 5974 | T3 n = 5974 | |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day ^ | 76.0 ± 47.7 | 218.8 ± 38.5 | 436.8 ± 157.8 | 62.3 ± 36.8 | 186.4 ± 35.8 | 388.6 ± 139.5 |

| Trait anxiety † (% (n) high) ^ | 23.4 (489) | 20.7 (433) | 20.4 (427) | 26.3 (1572) | 26.2 (1566) | 26.7 (1597) |

| Model 1 | 1 (ref.) | 0.94 (0.81–1.08) | 0.89 (0.76–1.03) | 1 (ref.) | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref.) | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) | 0.88 (0.75–1.02) | 1 (ref.) | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) |

| Women (n = 12,923) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Perceived Stress (PSS-10 Score < Sex-Specific Mean) | High Perceived Stress (PSS-10 Score ≥ Sex-Specific Mean) | |||||

| T1 n = 3216 | T2 n = 3216 | T3 n = 3216 | T1 n = 2759 | T2 n = 2758 | T3 n = 2758 | |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day ^ | 62.4 ± 37.3 | 186.9 ± 35.7 | 388.3 ± 135.1 | 62.2 ± 36.2 | 185.8 ± 36.0 | 389.0 ± 144.6 |

| Trait anxiety † (% (n) high) ^ | 24.6 (790) | 23.6 (759) | 25.0 (805) | 20.8 (574) | 22.6 (623) | 23.4 (646) |

| Model S3 | 1 (ref.) | 0.96 (0.86–1.08) | 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | 1 (ref.) | 1.14 (0.99–1.30) | 1.17 (1.02–1.34) |

| Men (n = 6274) | ||||||

| Low Perceived Stress (PSS-10 Score < Sex-Specific Mean) | High Perceived Stress (PSS-10 Score ≥ Sex-Specific Mean) | |||||

| T1 n = 1114 | T2 n = 1113 | T3 n = 1113 | T1 n = 978 | T2 n = 978 | T3 n = 978 | |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day^ | 78.7 ± 48.8 | 221.2 ± 37.2 | 435.8 ± 155.5 | 73.0 ± 46.4 | 215.9 ± 39.9 | 437.9 ± 160.5 |

| Trait anxiety † (% (n) high)^ | 23.9 (267) | 24.8 (276) | 23.9 (266) | 24.3 (238) | 25.2 (246) | 24.3 (238) |

| Model S3 | 1 (ref.) | 1.09 (0.89–1.33) | 1.02 (0.83–1.24) | 1 (ref.) | 1.17 (0.95–1.45) | 1.04 (0.84–1.30) |

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 n = 2092 | T2 n = 2091 | T3 n = 2091 | T1 n = 5975 | T2 n = 5974 | T3 n = 5974 | |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day ^ | 76.0 ± 47.7 | 218.8 ± 38.5 | 436.8 ± 157.8 | 62.3 ± 36.8 | 186.4 ± 35.8 | 388.6 ± 139.5 |

| Trait anxiety † (% (n) high) ^ | 23.4 (489) | 20.7 (433) | 20.4 (427) | 26.3 (1572) | 26.2 (1566) | 26.7 (1597) |

| Model S1 | 1 (ref.) | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 1 (ref.) | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) |

| Model S2 | 1 (ref.) | 1.00 (0.85–1.21) | 0.89 (0.75–1.07) | 1 (ref.) | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) |

| Model S3 | 1 (ref.) | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 0.89 (0.75–1.07) | 1 (ref.) | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paz-Graniel, I.; Kose, J.; Babio, N.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Touvier, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Andreeva, V.A. Caffeine Intake and Its Sex-Specific Association with General Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among General Population Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061242

Paz-Graniel I, Kose J, Babio N, Hercberg S, Galan P, Touvier M, Salas-Salvadó J, Andreeva VA. Caffeine Intake and Its Sex-Specific Association with General Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among General Population Adults. Nutrients. 2022; 14(6):1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061242

Chicago/Turabian StylePaz-Graniel, Indira, Junko Kose, Nancy Babio, Serge Hercberg, Pilar Galan, Mathilde Touvier, Jordi Salas-Salvadó, and Valentina A. Andreeva. 2022. "Caffeine Intake and Its Sex-Specific Association with General Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among General Population Adults" Nutrients 14, no. 6: 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061242

APA StylePaz-Graniel, I., Kose, J., Babio, N., Hercberg, S., Galan, P., Touvier, M., Salas-Salvadó, J., & Andreeva, V. A. (2022). Caffeine Intake and Its Sex-Specific Association with General Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among General Population Adults. Nutrients, 14(6), 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061242