Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab Fruit) Effect on Postprandial Glycemia in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Consideration

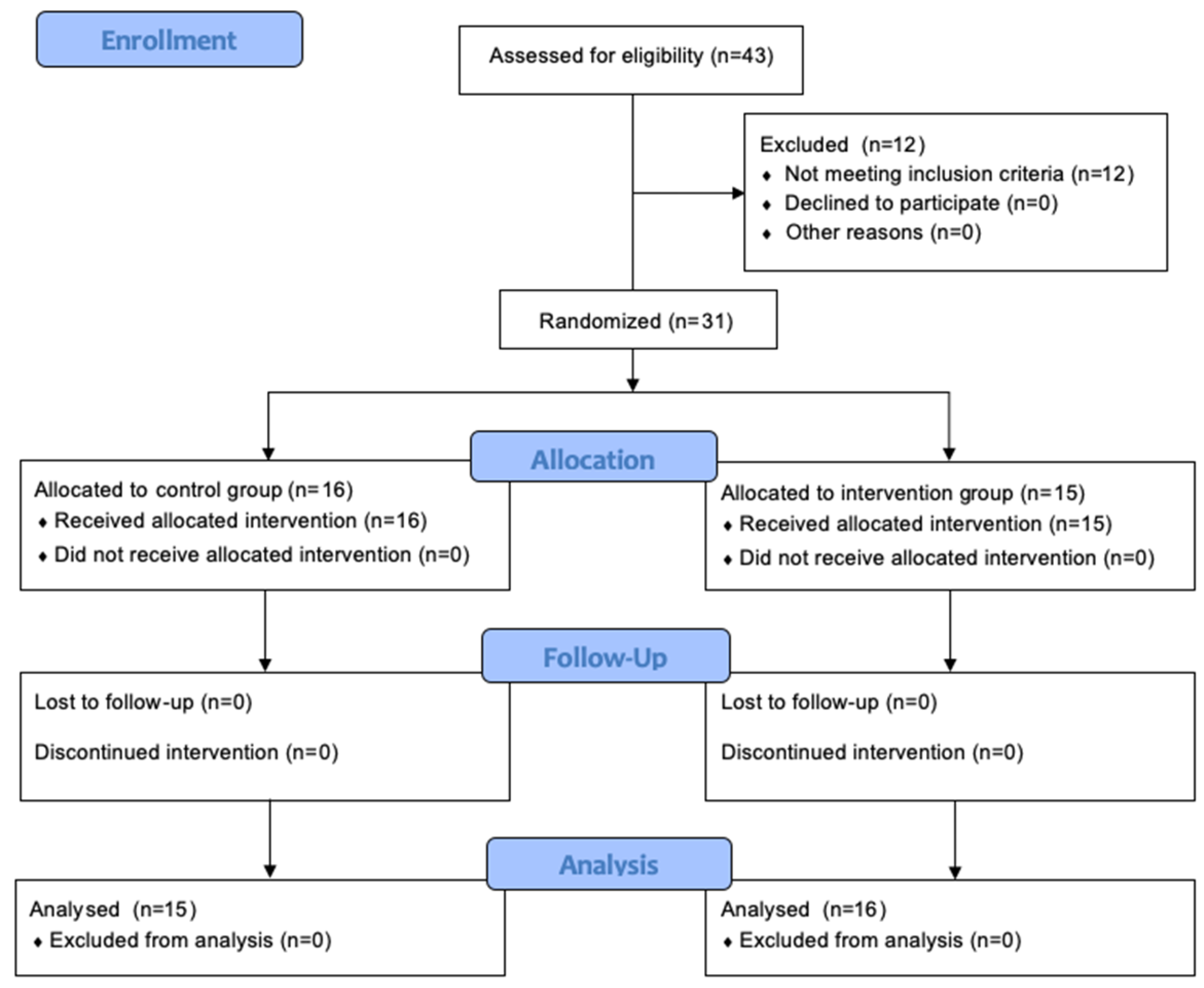

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Baobab Aqueous Extract Preparation

2.4. Interventions

2.5. Anthropometric Parameters Assessment

2.6. Dietary Ingestion Assessment

2.7. Chemical Analysis

2.8. Total Phenol, Proanthocyanidins, and Hydrolysable Tannins Content Assessment

2.9. Antioxidant Assays

2.10. Inhibition Capacity of O2•− Anion and NO Radical

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants of the Study

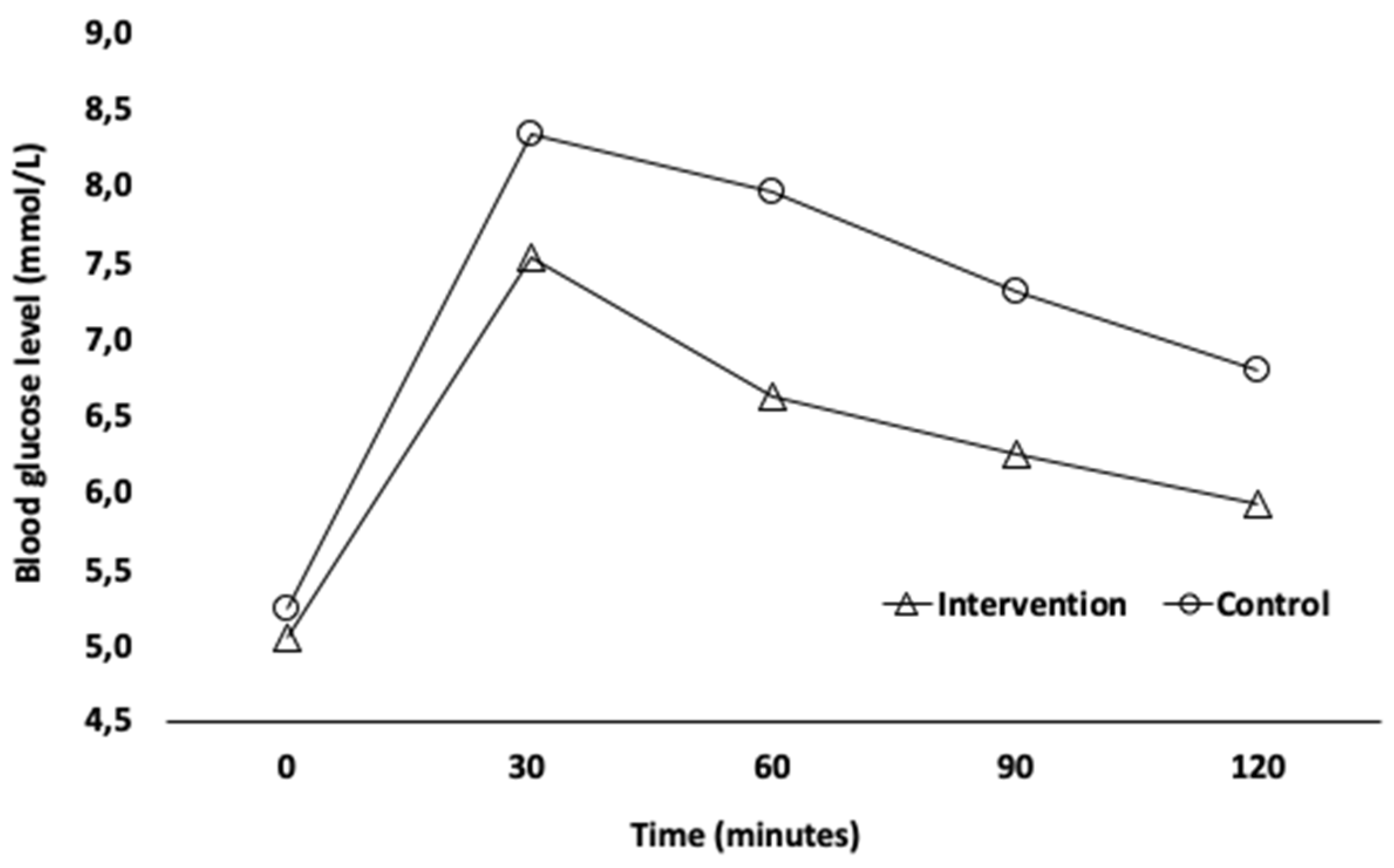

3.2. Postprandial Glycemia

3.3. Compounds Quantification and Antioxidant Capacity of BAE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Traditional chinese medicines in treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 726723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamatou, G.P.P.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A.M. An updated review of Adansonia digitata: A commercially important African tree. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Parasharami, V.; Rai, S. Medicinal Uses of Adansonia Digitata L.: An Endangered Tree Species. J. Pharm. Sci. Innov. 2013, 2, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, J.; Jain, M.K.; Singh, S.P.; Kamal, R.K.; Anuradha; Naz, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Mrityunjay, S.K. Adansonia digitata L. (baobab): A review of traditional information and taxonomic description. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coe, S.A.; Clegg, M.; Armengol, M.; Ryan, L. The polyphenol-rich baobab fruit (Adansonia digitata L.) reduces starch digestion and glycemic response in humans. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, S.; Ryan, L. White bread enriched with polyphenol extracts shows no effect on glycemic response or satiety, yet may increase postprandial insulin economy in healthy participants. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwarzo, M.Y.; Bako, H.Y. Hypoglycemic Activity of Methanolic Fruit Pulp Extract of Adansonia digitata on Blood Glucose Levels of Alloxan Induced Diabetic Rats. Int. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2013, 5, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evang, E.C.; Habte, T.Y.; Owino, W.O.; Krawinkel, M.B. Can the supplementary consumption of baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) fruit pulp improve the hemoglobin levels and iron status of schoolchildren in Kenya? Findings of a randomized controlled intervention trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2617–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tembo, D.T.; Holmes, M.J.; Marshall, L.J. Effect of thermal treatment and storage on bioactive compounds, organic acids and antioxidant activity of baobab fruit (Adansonia digitata) pulp from Malawi. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 58, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shahat, A.A. Procyanidins from Adansonia digitata. Pharm. Biol. 2006, 44, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.A. Chemical and nutrient analysis of baobab (Adansonia digitata) fruit and seed protein solubility. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2004, 59, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadare, F.J.; Linnemann, A.R.; Hounhouigan, J.D.; Nout, M.J.R.; Van Boekel, M.A.J.S. Baobab food products: A review on their composition and nutritional value. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, S62–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rama Prabha, M.; Vasantha, K. Antioxidant, cytotoxicity and polyphenolic content of calotropis procera (Ait.) R. Br. flowers. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, L.; Group, A.S.; Incorporated, M.; Human, B. Fractionation of Polymeric Procyanidins from Lowbush Blueberry and Quantification of Procyanidins in Selected Foods with an Optimized Normal-Phase HPLC−MS Fluorescent Detection Method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4852–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R.B.; Allen, P.R. Improved method for measuring hydrolyzable tannins using potassium iodate. Analyst 1998, 123, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaipong, K.; Boonprakob, U.; Crosby, K.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Hawkins Byrne, D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulueta, A.; Esteve, M.J.; Frígola, A. ORAC and TEAC assays comparison to measure the antioxidant capacity of food products. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, Z.B.; Pintao, A.M.; Costa, I.M.; Calejo, M.T.; Bandarra, N.M.; Abreu, P. Composition and in vitro antioxidant effects of jellyfish catostylus tagi from sado estuary (SW Portugal). J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2009, 18, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.H.; Liu, X.G.; Xing, R.E.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wang, P.B.; Li, C.P.; Li, P.C. In vitro determination of antioxidant activity of proteins from jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqinezhad, A.; Sharafi, M. In Vitro Screening for Antioxidant Activity and Cancer Suppressive Effect of Blackberry (Morus Nigra). Iran. J. Bot. 2008, 1, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Skytte, M.J.; Samkani, A.; Astrup, A.; Frystyk, J.; Rehfeld, J.; Larsen, T.M.; Krarup, T.; Haugaard, S.B. Effects of carbohydrate restriction on postprandial glucose metabolism, β-cell function, gut hormone secretion, and satiety in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 320, E7–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamanlis, A.; Chaikomin, R.; Doran, S.; Bellon, M.; Bartholomeusz, F.D.; Wishart, J.M.; Jones, K.L.; Horowitz, M.; Rayner, C.K. Effects of protein on glycemic and incretin responses and gastric emptying after oral glucose in healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 1364–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, D.J. The role of gut hormones in glucose homeostasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Avila, J.A.; Rodrigo García, J.; González Aguilar, G.A.; de la Rosa, L.A. The Antidiabetic Mechanisms of Polyphenols Related to Increased Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP1) and Insulin Signaling. Molecules 2017, 22, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kawakami, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Mazuka, M.; Yagi, N.; Sawazaki, A.; Koganei, M.; Natsume, M.; Kuriki, K.; Morimoto, T.; Asai, T.; et al. Effect of cacao polyphenol-rich chocolate on postprandial glycemia, insulin, and incretin secretion in healthy participants. Nutrition 2021, 85, 111128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, Y.; Osaki, N.; Hase, T.; Shimotoyodome, A. Ingestion of coffee polyphenols increases postprandial release of the active glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1(7-36)) amide in C57BL/6J mice. J. Nutr. Sci. 2015, 4, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzano, S.; Williamson, G. Polyphenols and phenolic acids from strawberry and apple decrease glucose uptake and transport by human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magaia, T.; Uamusse, A.; Sjöholm, I.; Skog, K. Dietary fiber, organic acids and minerals in selected wild edible fruits of Mozambique. Springerplus 2013, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gill, S.K.; Rossi, M.; Bajka, B.; Whelan, K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudonné, S.; Vitrac, X.; Coutière, P.; Woillez, M.; Mérillon, J.-M. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Yu, F.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, M.; Gao, H. Anti-inflammatory effects of grape seed procyanidin B2 on a diabetic pancreas. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 3065–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräunlich, M.; Slimestad, R.; Wangensteen, H.; Brede, C.; Malterud, K.E.; Barsett, H. Extracts, anthocyanins and procyanidins from Aronia melanocarpa as radical scavengers and enzyme inhibitors. Nutrients 2013, 5, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, E.; Scism-Bacon, J.L.; Glass, L.C. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: The role of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceriello, A.; Taboga, C.; Tonutti, L.; Quagliaro, L.; Piconi, L.; Bais, B.; Da Ros, R.; Motz, E. Evidence for an independent and cumulative effect of postprandial hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia on endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress generation: Effects of short- and long-term simvastatin treatment. Circulation 2002, 106, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceriello, A.; Quagliaro, L.; Piconi, L.; Assaloni, R.; Da Ros, R.; Maier, A.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D. Effect of Postprandial Hypertriglyceridemia and Hyperglycemia on Circulating Adhesion Molecules and Oxidative Stress Generation and the Possible Role of Simvastatin Treatment. Diabetes 2004, 53, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Control Group (n = 16) Mean (±SD) | Intervention Group (n = 15) Mean (±SD) | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.25 (±7.29) | 24.53 (±4.37) | 0.744 |

| Weight (m) | 70.05 (±18.51) | 65.36 (±9.67) | 0.382 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 (±0.07) | 1.65 (±0.08) | 0.553 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.81 (±5.59) | 23.82 (±3.33) | 0.551 |

| TEI at last meal before intervention (Kcal) | 336.24 (±194.33) | 595.05 (±578.01) | 0.118 |

| TEI * (Kcal) | 1705.63 (±495.51) | 1917.48 (±721.01) | 0.353 |

| Protein * (g) | 85.21 (±33.40) | 92.95 (±38.12) | 0.554 |

| Carbohydrate * (g) | 208.40 (±88.14) | 215.41 (±89.40) | 0.828 |

| Lipid * (g) | 60.18 (±22.15) | 78.34 (±35.56) | 0.104 |

| Time | Control Group Mean (±SD) mmol/L | Max/Min Values mmol/L | Intervention Group Mean (±SD) mmol/L | Max/Min Values mmol/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t0 | 5.25 (±0.39) | 5.94/4.61 | 5.04 (±0.31) | 5.94/4.61 |

| t30 | 8.31 (±1.30) | 10.71/5.49 | 7.54 (±1.00) | 9.55/5.55 |

| t60 | 7.93 (±1.56) | 11.49/5.88 | 6.62 (±1.14) | 8.33/4.38 |

| t90 | 7.22 (±1.31) | 9.93/4.77 | 6.24 (±0.61) | 7.71/5.49 |

| t120 | 6.75 (±1.19) | 9.44/4.83 | 5.92 (±0.57) | 6.99/4.83 |

| Variables | Control Group (n = 16) Mean (±SD) | Intervention Group (n = 15) Mean (±SD) | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUCi (0–120 min) | 253.68 (±101.14) | 172.44 (±61.92) | 0.012 |

| Cmax (mmol/L) | 8.66 (±1.37) | 7.71 (±0.85) | 0.029 |

| ΔCmax | 3.41 (±1.17) | 2.66 (±0.85) | 0.054 |

| Chemical Analysis | Mean (±SEM) /L | Mean (±SEM) /100 g | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds quantification | Total phenols (mg GAE, n = 7) | 937 (±15.79) | 702.39 (±11.85) |

| Proanthocyanins (mg PAE2, n = 7) | 448.43 (±14.46) | 336.33 (±10.85) | |

| Hydrolysable tannins (mg TAE, n = 6) | 316.84 (±6.28) | 237.63 (±4.71) | |

| Scavenging capacity | IC50 O2•− anion (mg GAE, n = 7) | 77.14 (±3.43) | 57.86 (±2.57) |

| IC50 NO• radical (mg GAE, n = 5) | 39.33 (±6.89) | 29.48 (±5.17) | |

| Antioxidant activity | FRAP (mg TE, n = 7) | 1719.40 (±45.92) | 1289.58 (±34.44) |

| ABTS (mg TE, n = 5) | 1339.19 (±55.53) | 1004.42 (±41.65) | |

| DPPH radical (mg TE, n = 5) | 1692.92 (±172.31) | 1269.72 (±129.23) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rita, K.; Bernardo, M.A.; Silva, M.L.; Brito, J.; Mesquita, M.F.; Pintão, A.M.; Moncada, M. Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab Fruit) Effect on Postprandial Glycemia in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020398

Rita K, Bernardo MA, Silva ML, Brito J, Mesquita MF, Pintão AM, Moncada M. Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab Fruit) Effect on Postprandial Glycemia in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2022; 14(2):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020398

Chicago/Turabian StyleRita, Keyla, Maria Alexandra Bernardo, Maria Leonor Silva, José Brito, Maria Fernanda Mesquita, Ana Maria Pintão, and Margarida Moncada. 2022. "Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab Fruit) Effect on Postprandial Glycemia in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 14, no. 2: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020398

APA StyleRita, K., Bernardo, M. A., Silva, M. L., Brito, J., Mesquita, M. F., Pintão, A. M., & Moncada, M. (2022). Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab Fruit) Effect on Postprandial Glycemia in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 14(2), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020398