1. Introduction

Genistein is a polyphenolic isoflavone naturally found in numerous staple crops, including soybeans and chickpeas. Many studies have reported genistein to possess various beneficial and protective physiological properties, with effects observed in metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and breast and prostate cancers in vivo [

1,

2]. The biological effects of isoflavone consumption have been attributed to structural similarity and function with human and animal estrogens. Specifically, due to structural similarity to 17b-estradiol, genistein has been observed to possess weak estrogenic activity and exhibit preferential binding to estrogen receptor ß [

2,

3].

The characterization of genistein metabolism and absorption is still ongoing, despite the well-studied physiological effects of genistein and other isoflavones. Dietary isoflavones exist as isoflavone-glycosides and are transformed by intestinal microbiota via bacterial enzymatic action to more potent metabolites, such as equol and O-desmethylan- lensin [

4]. Thus, individual differences in gut microbiota will consequently be expected to influence the potential for physiological effects associated with isoflavone ingestion [

5]. Current research has shown genistein administration in mice fed a high-fat diet ameliorated harmful effects associated with a high-fat diet through increasing populations of bacteria associated with reduced pro-inflammatory lipopolysaccharide and lower serum triglyceride levels [

1]. Another recent study has shown that isoflavone administration in vitro promoted short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production due to increased proliferation of SCFA-producing bacteria species from

Clostridium cluster XIVa,

Roseburia and

E. hallii [

4]. Additionally, maternal genistein intake perinatally and throughout pregnancy in mice mitigated harmful effects of a high-fat fed diet in dams and offspring and was associated with an increase in butyrate-producing gut bacteria [

6]. Increased SCFA production has been associated with inhibiting harmful pathogen growth, decreased intestinal pH, and upregulated brush border membrane (BBM) gene expression [

7,

8]. Taken together, these effects enhance micronutrient bioavailability.

Emerging evidence suggests that genistein exposure could be implicated in the altered expression of proteins involved in iron (Fe) transport. Genistein significantly increased Fe export through estrogen receptor ß-dependent p38 MAPK up-regulation through ceruloplasmin and ferroportin-1 in glial cells [

9]. However, another study found that genistein treatment of human hepatocytes increased both hepcidin transcription levels and promoter activity (hepcidin decreases intestinal Fe absorption by inhibiting ferroportin) [

10].

Despite the investigation of specific health benefits attributed to dietary genistein administration and subsequent knowledge of genistein ingestion on gut microbiota modulation and Fe transport, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding how genistein affects the brush border membrane (BBM) of the small intestine. As BBM functional capacity (i.e., digestive enzyme production) dictates the extent of food digestion and absorption, it is key to investigate the interactions between bioactive compounds in the diet and the BBM. There is also a lack of studies that specifically utilize the embryonic stage of the

Gallus gallus for elucidating the effects of genistein consumption on BBM development and functionality. Due to similarities in intestinal morphology, microbiota, and gene homology of duodenal mineral transporters between humans and

Gallus gallus, the

Gallus gallus has been used as a novel and cost-effective animal model to elucidate the physiological effects of plant bioactives and nutritional solutions relevant to human nutrition [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. To study the impact of bioactive on the embryonic stage, the intraamniotic administration approach can be utilized for testing the effects of the solution administered into the amniotic fluid on the different systems of interest in a closed system, where the amniotic fluid is naturally and orally consumed by the embryo starting at day 17 and is entirely consumed by hatch [

7,

11,

16,

17,

18].

In our present study, the effects of genistein intraamniotic administration on brush border membrane (BBM) functionality, intestinal morphology, and intestinal microbiome were studied in vivo using the embryonic stage of the

Gallus gallus. It was previously demonstrated that daidzein, another major isoflavone found in soybeans with estrogenic effects, altered BBM Fe transport proteins and cecal bacterial populations in the embryonic stage of the

Gallus gallus [

19]. Therefore, the first objective of this study was to evaluate genistein administration effects on BBM functionality through evaluating duodenal gene expression of biomarkers of mineral status, BBM digestive and absorptive ability, and inflammation. To accomplish this objective, we assessed the expression of duodenal cytochrome B (DcytB, a Fe-specific cytochrome reductase on the luminal side of the enterocyte) and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1, the primary transporter of Fe

2+ from the luminal side of the enterocyte), ferroportin (a basolateral exporter of dietary Fe

2+), liver hepcidin (decreases intestinal Fe absorption by inhibiting ferroportin), as well as duodenal ZnT7 (zinc transporter protein 7) and ZIP6 (zinc transporter) [

10]. BBM digestive and absorptive ability were evaluated by assessing duodenum morphology and gene expression of biomarkers of BBM digestive and absorptive ability (AP—aminopeptidase, SI—sucrase-isomaltase, and NaK/ATPase—sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase). In addition, systemic inflammatory status was evaluated using the expression of immunoregulatory cytokines (TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; and NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1). The second objective was to utilize PCR quantification to analyze duodenal microbial populations and next-generation sequencing to analyze the cecal microbiome to elucidate potential alterations in gut microbiota composition and function resulting from genistein administration. We hypothesize that when administered intraamniotically, genistein will alter mineral transport, cause favorable alterations in BBM functionality and development, and positively modulate the gut microbiota.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we have evaluated the effect of intraamniotic genistein administration on mineral transport, duodenal brush border membrane development and functionality, and intestinal microbiota. Although the ingestion of genistein has been associated with marked physiological changes associated with cancer and metabolic syndrome, further understanding of tissue-level effects associated with genistein exposure is needed [

6,

36,

37]. Presently, there is a paucity of studies in the literature that directly measure the effects of genistein on the combination of mineral transport, BBM morphology or functionality, and intestinal microbiota.

The intraamniotic administration of genistein positively affected intestinal development, as demonstrated by increased enterocyte proliferation. The duodenal morphometric analysis demonstrated a significant (

p < 0.05) dose-responsive effect of genistein treatment on increasing villus surface area versus the no-injection control (

Table 4), indicative of improved digestive enzyme and absorptive capacity [

7]. A significantly (

p < 0.05) reduced crypt depth was observed with genistein administration when compared to the H

2O injection control group (

Table 7), which has been shown to be a marker of efficient tissue turnover and good condition of the gut [

38]. The increase in villus surface area and reduction in crypt depth are in accordance with other genistein administration trials using the in vivo

Gallus gallus model [

39,

40]. Additionally, increased proliferation in total villi and crypt goblet cells and an increase in the proportion of villi acidic and crypt acidic (

p < 0.05) goblet cells were observed with genistein exposure compared to the no-injection and H

2O injection controls (

Table 5 and

Table 6). This indicates increased synthesis and secretion of acidic luminal mucin by duodenal goblet cells [

11,

12]. The major goblet cell mucins in the small intestine are mucin 2 proteins, gel-forming secretory mucins that facilitate hydrolysis and absorption of nutrients [

18,

41,

42,

43]. In addition to serving as a protective intestinal epithelial barrier, this mucin (mucin 2) also functions as a habitat that supports probiotic populations and promotes epithelial cell function [

44,

45]. Taken as a whole, this demonstrates that the intraamniotic administration of genistein can positively modulate BBM development and functionality.

The intestinal microbiota of the

Gallus gallus model is significantly and directly influenced by host genetics, environment, and diet [

23,

46]. At the phylum level, there is a significant resemblance between the gut microbiota of

Gallus gallus and humans, with

Bacteroidetes,

Firmicutes,

Proteobacteria, and

Actinobacteria representing the dominant bacterial phyla [

47]. Soy isoflavone treatment has been shown to alter intestinal bacterial populations in vivo, including increases in populations of SCFA-producing bacteria [

1,

36,

48]. In the duodenum, the relative abundance of

Bifidobacterium spp. considered a probiotic bacteria species, significantly increased with 2.5% genistein exposure compared with all other treatment groups (

Figure 2).

Lactobacillus spp. relative abundance was significantly increased with genistein exposure compared to the no-injection control. Further, linear discriminant analysis effect size (LefSe) analysis found that genistein treatment enriched bacterial pathways associated with

de novo synthesis of vitamin B

12 (

Figure S1), where bacteria from the

Lactobacillus genus represent a small number of bacteria known to encode the complete

de novo biosynthetic pathway of vitamin B

12 [

49,

50].

L. plantarum, a probiotic bacteria species associated with increased Fe absorption, was significantly increased in the genistein exposed-groups and 5% inulin control compared with the H

2O-injected control [

51].

L. plantarum produces glucosidases that can hydrolyze isoflavones (glycosides) into metabolites (aglycones) with increased antioxidant activity [

52]. Increased populations of health-promoting bacteria,

Bifidobacterium spp.,

Lactobacillus spp., and

L. plantarum, resulting from genistein exposure, can be attributed to increased acidic mucin production [

45,

53,

54]. Increased acidic mucin synthesis provides an environment conducive to the proliferation of these probiotic bacterial populations, which can be associated with an increased Paneth cell number per crypt and number of villi and crypt acidic goblet cells associated with genistein administration [

45,

53].

Clostridium spp. was significantly increased in the genistein-treated groups, and butyrate-producing (SCFA) bacteria, such as

Roseburia spp. and

E. hallii from

Clostridium cluster XIVa, have previously been observed to be increased with genistein exposure in vitro [

4]. The increase in

Lactobacillus spp.,

Bifidobacterium spp., and

Clostridium spp. abundance may further contribute to increased mineral bioavailability as these genera house SCFA-producing species, where SCFAs reduce the intestinal pH and thus may increase mineral (Fe and Zn) solubility and absorption [

7,

18,

55].

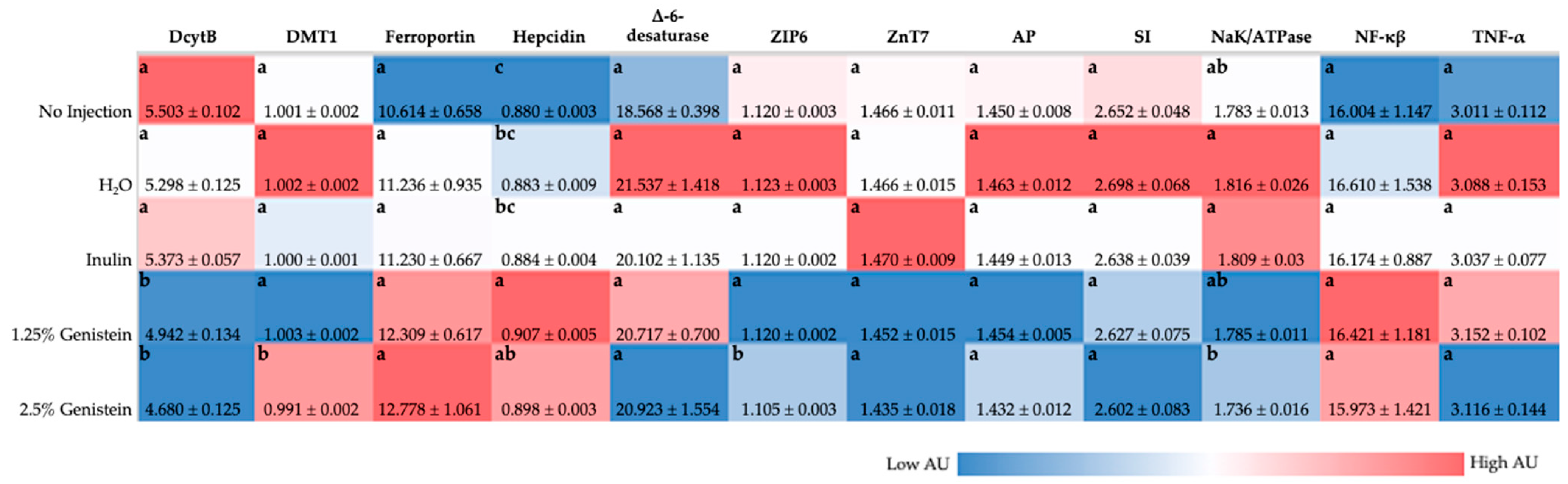

Our previous research suggested soy isoflavone (daidzein) intraamniotic administration has the potential to improve dietary Fe bioavailability [

19]. In our current study, BBM gene expression analysis (

Figure 1) demonstrated that genistein downregulated DMT1 (transports Fe

2+ into duodenal enterocyte) and DcytB (reduces Fe

3+ to Fe

2+) and upregulated ferroportin (transports Fe

2+ into blood) and hepcidin (binds to ferroportin, causes ferroportin internalization and degradation), relative to the control group, though these results were not necessarily dose-dependent or significant [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Based on protein functionalities in Fe sufficient or excess scenarios, it is expected that DcytB, DMT1, and ferroportin would be downregulated, whereas hepcidin would be upregulated [

57,

58,

60,

61,

62,

63]. Though upregulation of ferroportin has previously been associated with Fe deficiency, genistein treatment was found to upregulate ferroportin expression in glial cells through estrogen receptor ß-dependent p38 MAPK activation, independent of Fe status [

9,

63]. Genistein administration has been shown to upregulate hepcidin expression, directly influencing ferroportin expression in in vivo and in vitro liver cell models [

10]. Blood Hb levels were increased with genistein administration compared with the controls, which, taken together with Fe gene expression analysis, may indicate Fe status was improved by genistein administration. Genistein exposure resulted in ZIP6 (imports zinc across cell membrane) downregulation in comparison with the no-injection control, potentially indicative of improved zinc status with genistein administration [

64,

65], or could be associated with estrogenic effects of soy isoflavones, where ZIP6 expression was found to be modulated with anti-estrogen treatment in breast cells [

66,

67]. Although Zn absorption occurs in the duodenum, it has been suggested that the ileum is the leading site of Zn absorption in

Gallus gallus [

68], where future studies should focus on the Zn-transporter gene expression in the ileum to further understand the effects of genistein administration on Zn transport and absorption. Overall, alterations in mineral transport and hemoglobin concentration associated with improvements in mineral status can potentially be attributed to the combination of increased bacterial production of SCFA and increased proportion of acidic goblet cells associated with genistein exposure, resulting in a lowered intestinal pH and increased mineral solubility, thus improving mineral absorption [

12,

18,

69].

Increases in body weight were observed in a dose-dependent manner compared with the controls, with the 2.5% genistein treatment group being significantly higher (

p < 0.05) than the no-injection control (

Table 2). Given the short exposure time, a significant increase in body weight is unexpected, but when taken with improved Fe status and BBM development, and given that the in vivo

Gallus gallus model is sensitive to dietary Fe and Zn deficiencies [

55,

70], a significant increase in body weight confirms the positive developmental effects related to genistein exposure [

71]. Additional studies are warranted to assess shifts in mineral status, intestinal functionality and development, and intestinal microbiota post-hatch and during a long-term feeding trial associated with genistein consumption.