Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mental Health in Adults: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

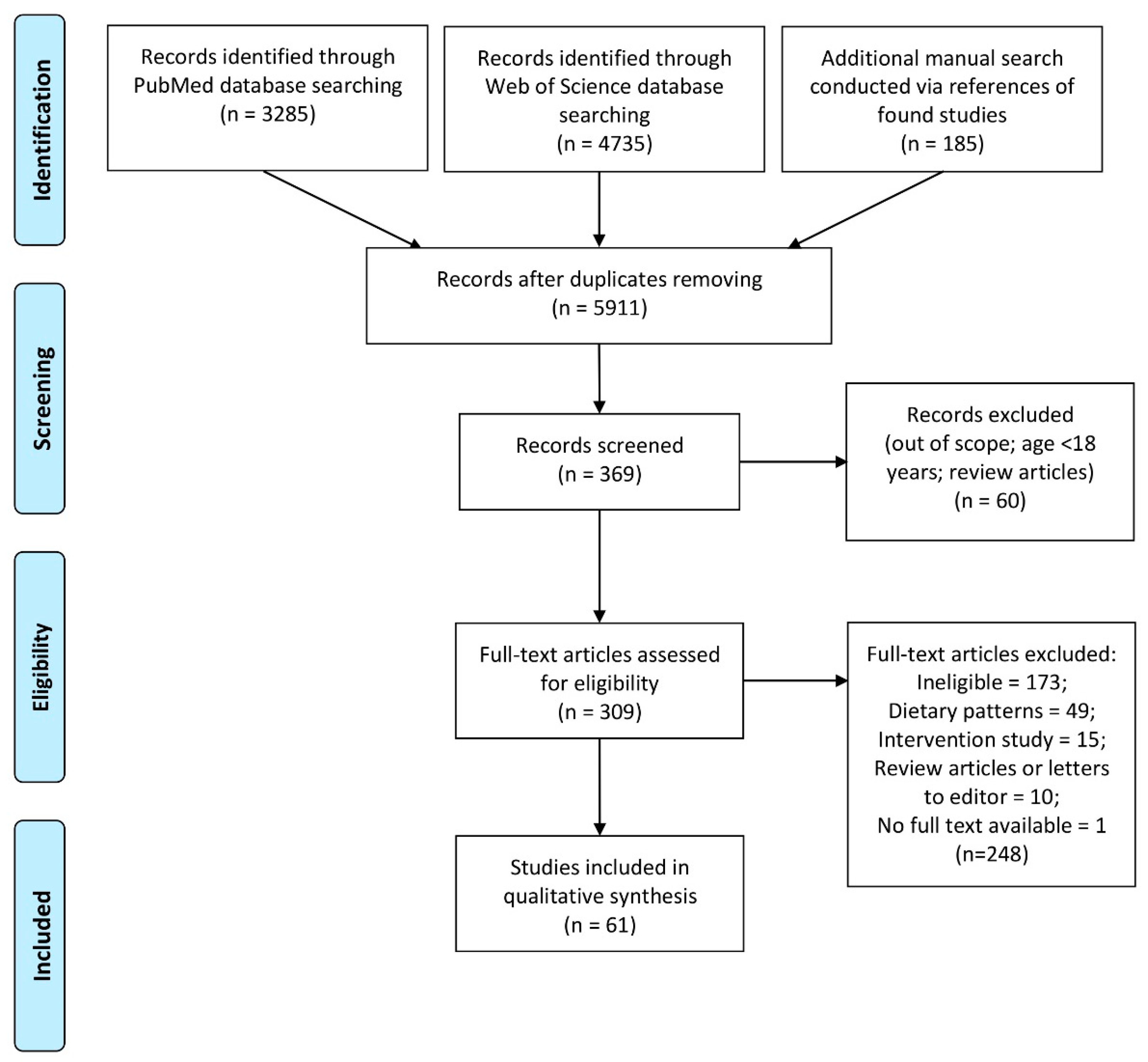

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, ICD-10 Version. 2016. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- WHO. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- WHO. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Available online: Apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R8-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Wattick, R.A.; Hagedorn, R.L.; Olfert, M.D. Relationship between Diet and Mental Health in a Young Adult Appalachian College Population. Nutrients 2018, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasalizad Farhangi, M.; Dehghan, P.; Jahangiry, L. Mental health problems in relation to eating behavior patterns, nutrient intakes and health related quality of life among Iranian female adolescents. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parletta, N.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Cho, J.; Wilson, A.; Bogomolova, S.; Villani, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Niyonsenga, T.; Blunden, S.; Meyer, B.; et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N.; O’Neil, A.; Opie, R.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Cotton, S.; Mohebbi, M.; Castle, D.; Dash, S.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M.L.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med. 2017, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapsell, L.C.; Neale, E.P.; Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Foods, Nutrients, and Dietary Patterns: Interconnections and Implications for Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaChance, L.; Ramsey, D. Food, mood, and brain health: Implications for the modern clinician. Mo. Med. 2015, 112, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- LaChance, L.R.; Ramsey, D. Antidepressant foods: An evidence-based nutrient profiling system for depression. World J. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis. Nutrition 2016, 32, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saneei, P.; Saghafian, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A.R. “Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis”: Further analysis is required. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1162–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada, T.R. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis. Nutrition 2018, 45, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghafian, F.; Malmir, H.; Saneei, P.; Milajerdi, A.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of depression: Accumulative evidence from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuck, N.J.; Farrow, C.; Thomas, J.M. Assessing the effects of vegetable consumption on the psychological health of healthy adults: A systematic review of prospective research. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, C.; McKinley, M.C.; Woodside, J.V. The potential role of fruit and vegetables in aspects of psychological well-being: A review of the literature and future directions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knüppel, A.; Shipley, M.J.; Llewellyn, C.H.; Brunner, E.J. Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: Prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, S.; Song, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Exploration of the association between dietary fiber intake and depressive symptoms in adults. Nutrition 2018, 54, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwisch, J.E.; Hale, L.; Garcia, L.; Malaspina, D.; Opler, M.G.; Payne, M.E.; Rossom, R.C.; Lane, D. High glycemic index diet as a risk factor for depression: Analyses from the Women’s Health Initiative. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraian, A.; Ghanizadeh, A.; Kazemeini, F. Vitamin C as an adjuvant for treating major depressive disorder and suicidal behavior, a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Trials 2015, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, K.; Stojanovska, L.; Apostolopoulos, V. The Effects of Vitamin B in Depression. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 4317–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Bandinelli, S.; Penninx, B.W.; Corsi, A.M.; Lauretani, F.; Vazzana, R.; Semba, R.D.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. The relationship between plasma carotenoids and depressive symptoms in older persons. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 13, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrug, S.; Orihuela, C.; Mrug, M.; Sanders, P.W. Sodium and potassium excretion predict increased depression in urban adolescents. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureda, A.; Tejada, S. Polyphenols and depression: From chemistry to medicine. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015, 16, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, U.E.; Beglinger, C.; Schweinfurth, N.; Walter, M.; Borgwardt, S. Nutritional aspects of depression. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.P.; Rogers, R. Positive effects of a healthy snack (fruit) versus an unhealthy snack (chocolate/crisps) on subjective reports of mental and physical health: A preliminary intervention study. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies. Chapter 13.5.2.3. Available online: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Luchini, C.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J. Meta-Anal. 2017, 5, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Association between fruit/vegetable consumption and mental-health-related quality of life, major depression, and generalized anxiety disorder: A longitudinal study in Thailand. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2019, 13, 88246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.H.; Tseng, L.H.; Wei, J.; Lin, C.H.; Wang, T.J.; Liang, S.Y. Food pattern and quality of life in metabolic syndrome patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting in Taiwan. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 10, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, K.M.; Sharpe, P.A.; Wilcox, S.; Hutto, B.E. Depressive symptoms are associated with dietary intake but not physical activity among overweight and obese women from disadvantaged neighborhoods. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, M.; Marston, L.; Walters, K.; D’Costa, G.; King, M.; Nazareth, I. Psychological distress, gender and dietary factors in South Asians: A cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1538–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.; Nigg, C.R.; Pagano, I.S.; Motl, R.W.; Horwath, C.; Dishman, R.K. Associations of quality of life with physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, and physical inactivity in a free living, multiethnic population in Hawaii: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.W.; Tan, A.; Schaffir, J. Relationships between stress, demographics and dietary intake behaviours among low-income pregnant women with overweight or obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Shi, Y.X.; Yu, F.N.; Zhao, H.Z.; Zhang, J.H.; Song, M. Association between vegetables and fruits consumption and depressive symptoms in a middle-aged Chinese population: An observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, 15374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehlich, K.H.; Beller, J.; Lange-Asschenfeldt, B.; Köcher, W.; Meinke, M.C.; Lademann, J. Consumption of fruits and vegetables: Improved physical health, mental health, physical functioning and cognitive health in older adults from 11 European countries. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlich, K.H.; Beller, J.; Lange-Asschenfeldt, B.; Köcher, W.; Meinke, M.C.; Lademann, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with improved mental and cognitive health in older adults from non-Western developing countries. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.M.J.; Abdin, E.; Jeyagurunathan, A.; Shafie, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.J.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Exploring Singapore’s consumption of local fish, vegetables and fruits, meat and problematic alcohol use as risk factors of depression and subsyndromal depression in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean, N.; Howley, P.; Ensor, J. Lettuce be happy: A longitudinal UK study on the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and well-being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 222, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, F.P.; Relja, A.; Simunovic Filipcic, I.; Polasek, O.; Kolcic, I. Mediterranean diet and mental distress: 10,001 Dalmatians study. Mediterranean diet and mental distress: 10,001 Dalmatians study. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1314–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azupogo, F.; Seidu, J.A.; Issaka, Y.B. Higher vegetable intake and vegetable variety is associated with a better self-reported health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) in a cross-sectional survey of rural northern Ghanaian women in fertile age. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharzadeh, E.; Siassi, F.; Qorbani, M.; Koohdani, F.; Pak, N.; Sotoudeh, G. Fruits and vegetables intake and its subgroups are related to depression: A cross-sectional study from a developing country. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2018, 17, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, J.K.; Soo, J.; Zevon, E.S.; Chen, Y.; Kim, E.S.; Kubzansky, L.D. Longitudinal associations between psychological well-being and the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookie, K.L.; Best, G.I.; Conner, T.S. Intake of Raw Fruits and Vegetables Is Associated with Better Mental Health Than Intake of Processed Fruits and Vegetables. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, E.; Hockey, M.; Ruusunen, A.; Jacka, F.N. Does Fruit and Vegetable Consumption During Adolescence Predict Adult Depression? A Longitudinal Study of US Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyväkorpi, S.K.; Urtamo, A.; Pitkala, K.H.; Strandberg, T.E. Happiness of the oldest-old men is associated with fruit and vegetable intakes. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 9, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Sofi, F.; Vannetti, F.; Caiani, S.; Pasquini, G.; Lova, R.M.; Cecchi, F.; Sorbi, S.; Macchi, C. Mediterranean diet, food consumption and risk of late-life depression: The Mugello Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 2, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafian, F.; Malmir, H.; Saneei, P.; Keshteli, A.H.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J.; Afshar, H.; Siassi, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Adibi, P. Consumption of fruit and vegetables in relation with psychological disorders in Iranian adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.L.; Storm, V.; Reinwand, D.A.; Wienert, J.; de Vries, H.; Lippke, S. Understanding the Positive Associations of Sleep, Physical Activity, Fruit and Vegetable Intake as Predictors of Quality of Life and Subjective Health Across Age Groups: A Theory Based, Cross-Sectional Web-Based Study. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.D.; Ellis, E.M. Sex Differences in the Association of Perceived Ambiguity, Cancer Fatalism, and Health-Related Self-Efficacy with Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishwajit, G.; O’Leary, D.P.; Ghosh, S.; Sanni, Y.; Shangfeng, T.; Zhanchun, F. Association between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in South Asia. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.; Ding, D.; Mihrshahi, S. Fruit and vegetable consumption and psychological distress: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses based on a large Australian sample. BMJ Open 2017, 7, 014201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Dietary consumption and happiness and depression among university students: A cross-national survey. J. Psychol. Afr. 2017, 27, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.M.L.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E.; Miller, D.K. Fruit and vegetable intake, physical activity, and depressive symptoms in the African American Health (AAH) study. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 220, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, A.; Rohrmann, S.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Lasserre, A.M.; Strippoli, M.F.; Eichholzer, M.; Glaus, J.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Vollenweider, P.; Preisig, M. Adherence to dietary recommendations is not associated with depression in two Swiss population-based samples. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 252, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.M.; Frye, K.; Morrell, J.S.; Carey, G. Fruit and Vegetable Intake Predicts Positive Affect. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 809–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniczak, I.; Cáceres-DelAguila, J.A.; Maguiña, J.L.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A. Fruits and vegetables consumption and depressive symptoms: A population-based study in Peru. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 0186379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Tsai, A.C. Combined association of leisure-time physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption with depressive symptoms in older Taiwanese: Results of a national cohort study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesani, A.; Mohammadpoorasl, A.; Javadi, M.; Esfeh, J.M.; Fakhari, A. Eating breakfast, fruit and vegetable intake and their relation with happiness in college students. Eat. Weight Disord. 2016, 21, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujcic, R.; Oswald, J.A. Evolution of Well-Being and Happiness after Increases in Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beezhold, B.; Radnitz, C.; Rinne, A.; DiMatteo, J. Vegans report less stress and anxiety than omnivores. Nutr. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, T.S.; Brookie, K.L.; Richardson, A.C.; Polak, M.A. On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsbury, M.; Dupuis, G.; Jacka, F.; Roy-Gagnon, M.H.; McMartin, S.E.; Colman, I. Associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and depressive symptoms: Evidence from a national Canadian longitudinal survey. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.C.; Wyatt, L.C.; Kranick, J.A.; Islam, N.S.; Devia, C.; Horowitz, C.; Trinh-Shevrin, C. Physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake, and health-related quality of life among older Chinese, Hispanics, and Blacks in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papier, K.; Ahmed, F.; Lee, P.; Wiseman, J. Stress and dietary behaviour among first-year university students in Australia: Sex differences. Nutrition 2015, 31, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, A.; Rohrmann, S.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Mohler-Kuo, M.; Eichholzer, M. Associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and psychological distress: Results from a population-based study. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Adetunji, H.; Oskrochi, R. Food and mental health: Relationship between food and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among university students in the United Kingdom. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health. 2014, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Dobson, A.J.; Mishra, G.D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-age women: Results from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, T.; Kenkre, T.S.; Thompson, D.V.; Bittner, V.A.; Whittaker, K.; Eastwood, J.A.; Eteiba, W.; Cornell, C.E.; Krantz, D.S.; Pepine, C.J.; et al. Depression, dietary habits, and cardiovascular events among women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaraly, T.N.; Sabia, S.; Shipley, M.J.; Batty, G.D.; Kivimaki, M. Adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and future depressive symptoms: Evidence for sex differentials in the Whitehall II study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMartin, S.E.; Jacka, F.N.; Colman, I. The association between fruit and vegetable consumption and mental health disorders: Evidence from five waves of a national survey of Canadians. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B.J.; Kolanu, N.; Griffiths, D.A.; Grounds, B.; Howe, P.R.; Kreis, I.A. Food groups and fatty acids associated with self-reported depression: An analysis from the Australian National Nutrition and Health Surveys. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, K.; Guo, H.; Kakizaki, M.; Cui, Y.; Ohmori-Matsuda, K.; Guan, L.; Hozawa, A.; Kuriyama, S.; Tsuboya, T.; Ohrui, T.; et al. A tomato-rich diet is related to depressive symptoms among an elderly population aged 70 years and over: A population-based, cross-sectional analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 144, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roohafza, H.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Sadeghi, M.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Sajjadi, F.; Khosravi-Boroujeni, H. The association between stress levels and food consumption among Iranian population. Arch. Iran. Med. 2013, 16, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- White, B.A.; Horwath, C.C.; Conner, T.S. Many apples a day keep the blues away-daily experiences of negative and positive affect and food consumption in young adults. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J.; Stewart-Brown, S. Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K.M.; Kaplan, B.J. Food intake and blood cholesterol levels of community-based adults with mood disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, M.E.; Steck, S.E.; George, R.R.; Steffens, D.C. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intakes are lower in older adults with depression. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 2022–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.C.; Chang, T.L.; Chi, S.H. Frequent consumption of vegetables predicts lower risk of depression in older Taiwanese—results of a prospective population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttinen, H.; Männistö, S.; Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S.; Silventoinen, K.; Haukkala, A. Emotional eating, depressive symptoms and self-reported food consumption. A population-based study. Appetite 2010, 54, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamplekou, E.; Bountziouka, V.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Zeimbekis, A.; Tsakoundakis, N.; Papaerakleous, N.; Gotsis, E.; Metallinos, G.; Pounis, G.; Polychronopoulos, E.; et al. Urban environment, physical inactivity and unhealthy dietary habits correlate to depression among elderly living in eastern Mediterranean islands: The MEDIS (MEDiterranean ISlands Elderly) study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2010, 14, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; McKeown, R.E. Cross-sectional assessment of diet quality in individuals with a lifetime history of attempted suicide. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 165, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczyk, R.T.; El Ansari, W.; Maxwell, A.E. Food consumption frequency and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among students in three European countries. Nutr. J. 2009, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfhag, K.; Rasmussen, F. Food consumption, eating behaviour and self-esteem among single v. married and cohabiting mothers and their 12-year-old children. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Giltay, E.J.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Zitman, F.G.; Buijsse, B.; Kromhout, D. Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: The Zutphen Elderly Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xie, B.; Chou, C.P.; Koprowski, C.; Zhou, D.; Palmer, P.; Sun, P.; Guo, Q.; Duan, L.; Sun, X.; et al. Perceived stress, depression and food consumption frequency in the college students of China Seven Cities. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloniemi, H.; Ek, E.; Laitinen, J. Optimism, dietary habits, body mass index and smoking among young Finnish adults. Appetite 2005, 45, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S.; Lahelma, E.; Roos, E. Mental health and food habits among employed women and men. Appetite 2004, 42, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.; Benton, D. The relationship between diet and mental-health. Person. Individ. Diff. 1993, 14, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization. Fruit and Vegetables for Health. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Workshop, 1–3 September 2004, Kobe, Japan. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-y5861e.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- National Health Service (NHS). 5 A Day Portion Sizes. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/5-a-day-portion-sizes/ (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- American Heart Association (AHA). Fruits and Vegetables Serving Sizes. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/add-color/fruits-and-vegetables-serving-sizes (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Better Health Foundation (PBH). Experts Recommend 5-9 Servings of Fruits & Veggies Daily. Available online: https://fruitsandveggies.org/stories/iv-for-090611-leanne-heckenlaible (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Office of Disease Prevention and health Promotion (ODPHP). Build a Healthy Base. Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2000/document/build.htm (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Liu, R.H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.; Young, H.A. Role of fruit juice in achieving the 5-a-day recommendation for fruit and vegetable intake. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ref. | Study Details | Observation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Country/Location | Study Group | Time | |

| [40] | Chang et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional study within Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children in Michigan, USA | United States of America (USA) | Non-Hispanic women | May to August 2010 |

| [41] | Cheng et al., 2019 | Observational study | China/Linyi, Shandong Province | Middle-aged Chinese population | May 2016 to June 2017 |

| [42] | Gehlich et al., 2019 | Longitudinal population-based study within Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland | Older adults | 2011 and 2013 waves of the study |

| [43] | Gehlich et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional, population-based study based on the WHO Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) | China, India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Ghana | Adults ≥ 50 years | 2007–2010 |

| [44] | Goh et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional, population-based study within Well-being of the Singapore Elderly (WiSE) Study | Singapore | Adults ≥ 60 years | December 2013 |

| [45] | Ocean et al., 2019 | Longitudinal study within the UK Household Longitudinal Survey (UKHLS) | United Kingdom (UK) | General population | 2010–2017 waves of the study |

| [35] | Pengpid et al., 2019 | Longitudinal study within a lifestyle intervention trial | Thailand/Nakhon Pathom province | Temple members with prediabetes and/or prehypertension | 2016–2018 |

| [46] | Salvatore et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional study—10,001 Dalmatians Study | Croatia/Split and Island of Korčula | Adults | 2007–2015 |

| [47] | Azupogo et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study | Ghana/Tolon and Savelugu Districts | Rural women in fertile age | April to May 2016 |

| [48] | Baharzadeh et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study | Iran/Khorramabad | Women attending health centers | May to October 2017 |

| [49] | Boehm et al., 2018 | Observational population-based study within English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | UK | Adults ≥ 50 years | 2006–2013 waves of the study |

| [50] | Brookie et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study | New Zealand, USA | Young adults aged 18–25 recruited as part of psychology course at university, or through an online crowdsourcing marketplace | March to June 2017 |

| [51] | Hoare et al., 2018 | Longitudinal, population-based study | USA | Adolescents at baseline, adults in follow-up | 1994–1995 and 2007–2008 waves of the study |

| [52] | Jyväkorpi et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study in longitudinal Helsinki Businessmen Study (HBS) cohort | Finland/Helsinki | Oldest-old, home-dwelling men | 2016 |

| [53] | Pagliai et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study—Mugello Study | Italy/Florence | Nonagenarians (90–99 years) | Not specified |

| [54] | Saghafian et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study within Study on the Epidemiology of Psychological, Alimentary Health and Nutrition (SEPAHAN) | Iran | Adults working in health centers | 2010 1 |

| [55] | Tan et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional study | Germany, Netherlands | Adults ≥ 20 years | 2013–2015 |

| [56] | Welch and-- Ellis 2018 | Cross-sectional, population-based study—Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) | USA | Adults | 2011–2017 waves of the study |

| [57] | Bishwajit et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional study based on World Health Survey of WHO | Bangladesh, India, Nepal | Adults | 2002–2004 |

| [58] | Nguyen et al., 2017 | Longitudinal, cross-sectional, population-based study—Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study | Australia/New South Wales | Adults | 2006–2008, 2010 |

| [59] | Peltzer and Pengpid 2017 | Cross-sectional study | Bangladesh, Barbados, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Egypt, Grenada, India, Indonesia, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mauritius, Namibia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Venezuela, Vietnam | University students | Not specified |

| [60] | Ribeiro et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional and longitudinal study—African American Health (AAH) | USA/Missouri, St. Louis | Urban-dwelling African Americans | 2007–2010 |

| [61] | Richard et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional, population-based study—based on COhorte LAUSannoise(CoLaus)/Psychiatric CoLaus (PsyCoLaus) and Swiss Health Survey (SHS) | Switzerland | Adults ≥ 40 years | 2009–2012 |

| [62] | Warner et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional study | USA/New England | University students | 2013–2014 |

| [63] | Wolniczak et al., 2017 | Observational, population-based study within Health Questionnaire of the Demographic Health Survey—Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar (ENDES) | Peru | Adults | 2014 |

| [64] | Chi et al., 2016 | Longitudinal study—Taiwan Longitudinal Survey on Aging (TLSA) | Taiwan | Adults ≥ 53 year | 1999, 2003 |

| [65] | Lesani et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional study | Iran | Students of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences | Not specified |

| [66] | Mujcic and Oswald 2016 | Longitudinal, population-based study—Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey | Australia | Adolescents or adults at baseline, adults in follow-up | 2007, 2009, 2013 |

| [67] | Beezhold et al., 2015 | Observational study | USA, Canada and other countries (16%) | Adults | 2013 |

| [68] | Conner et al., 2015 | Micro-longitudinal study within Daily Life Study | New Zealand | Students at the University of Otago | 2013 |

| [69] | Kingsbury et al., 2015 | Longitudinal population-based study—National Population Health Survey (NPHS) | Canada | Adults | 2002–2011 |

| [70] | Kwon et al., 2015 | Observational study within Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Health Across the United States (REACH US) | USA/New York | Minority groups in ethnic enclaves | 2009–2012 |

| [71] | Papier et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional study | Australia | First year undergraduate students of Griffith University | 2012–2013 |

| [72] | Richard et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional, population-based study—2012 Swiss Health Survey | Switzerland | Adolescents and adults ≥ 15 years | 2012–2013 |

| [73] | El Ansari et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional study | England, Wales, Northern Ireland | Undergraduate students | 2007–2008 |

| [74] | Mihrshahi et al., 2014 | Longitudinal study | Australia | Women | 2004, 2007, 2010 |

| [75] | Rutledge et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional study—Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) | USA | Women | 1996–2000 with median of 5.9 years of follow up |

| [37] | Whitaker et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional study—Sisters Taking Action for Real Success (STARS) | USA/Columbia | Overweight and obese women from economically disadvantaged neighborhoods | June to July 2008 1 |

| [76] | Akbaraly et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional study—Whitehall II | UK | Adults | 1985–1988, 1991–1993, 2003–2004, 2008–2009 |

| [38] | Bhattacharyya et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional study | India/Goa | Adults | April 2004 to January 2005 |

| [77] | McMartin et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional, population-based study within Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) | Canada | Adolescents and adults ≥ 12 years | 2000–2009 |

| [78] | Meyer et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional, population-based study—Australian National Nutrition Survey (NNS), Australian National Health Survey (NHS) | Australia | Adults | 1995 |

| [79] | Niu et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional, population-based study—Tsurugaya Project | Japan/Sendai | Adults ≥ 70 year | 2002 |

| [80] | Roohafza et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional study within Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP) | Iran/Isfahan, Arak, Najafabad | Adults | Not specified |

| [81] | White et al., 2013 | Micro-longitudinal study | New Zealand/Otago | Undergraduate students | April 2008 to August 2009 |

| [82] | Blanchflower et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional, population-based study of the data from Welsh Health Survey of 2007–2010, Scottish Health Survey of 2008 and Health Survey of England in 2008 | UK | Adults | 2007–2010 |

| [83] | Davison and Kaplan 2012 | Cross-sectional study | Canada | Adult members of the Mood Disorders Association of British Columbia (MDABC) | Not specified |

| [84] | Payne et al., 2012 | Case-control study within longitudinal clinical study NeuroCognitive Outcomes of Depression in the Elderly (NCODE) | USA | Adults ≥ 60 year | 1999–2007 |

| [85] | Tsai et al., 2011 | Prospective population-based study—Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan (SHLSET) | Taiwan | Adults ≥ 65 years | 1999, 2003 |

| [36] | Tung et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional study | Taiwan/Taipei | Adults after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery | February to June 2009 |

| [39] | Chai et al., 2010 | Longitudinal study | USA/Hawaii | Adults | 2-year study period |

| [86] | Konttinen et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional, population-based study—National Cardiovascular Risk Factor Survey (The FINRISK Study)/Dietary, Lifestyle and Genetic Determinants of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome (DILGOM substudy) | Finland | Adults | 2007 |

| [87] | Mamplekou et al., 2010 | Longitudinal population-based study—Mediterranean Islands Elderly Study (MEDIS) | Cyprus, Greece | Adults ≥ 65 years | 2005–2007 |

| [88] | Li et al., 2009 | Longitudinal cross-sectional study—Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) | USA | Adults | 1988–1994 |

| [89] | Mikolajczyk et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional study—Cross National Student Health Survey (CNSHS) | Germany, Poland, Bulgaria | First-year students | 2005 |

| [90] | Elfhag and Rasmussen 2008 | Cross-sectional study in Parental Influences on Their Children’s Health (PITCH) data set | Sweden | Women | 2000 |

| [91] | Giltay et al., 2007 | Longitudinal study within Zutphen Elderly Study | Netherlands | Elderly community-living men | 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 |

| [92] | Liu et al., 2007 | Cross-sectional study—China Seven City Study | China | College students | November 2003 to January 2004 |

| [93] | Kelloniemi et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional, population-based study | Finland | 31-year-old adults | 1997–1998 |

| [94] | Sarlio-Lähteenkorva et al., 2004 | Cross-sectional study within Helsinki Health Study | Finland/Helsinki | Adults 40–60 years | 2000–2001 |

| [95] | Cook and Benton 1993 | Cross-sectional, population-based study | Wales/Swansea | Adults | Not specified |

| Ref. | Exposure | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Measure of Fruit and Vegetable | Other Fruit/Vegetable Products | Assessment | Psychological Measure | |

| [40] | Rapid Food Screener | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including juices Vegetables including salads, soups | Stress | Perceived Stress Scale |

| [41] | Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire | Portion size, frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [42] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption | Frequency of consumption | Not specified |

|

|

| [43] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day with a list of country-specific examples of fruits and vegetables | Frequency of consumption | Not specified |

|

|

| [44] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption over the last 3 days | Frequency of consumption | Vegetables including salads | Depression and subsyndromal depression | Geriatric Mental State (GMS) |

| [45] | Questions about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day when they are consumed, fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical week | Portion size, frequency of consumption | Not specified | Mental well-being | 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) |

| [35] | WHO STEPS Instrument | Frequency of consumption | Not specified |

|

|

| [46] | Food frequency questionnaire with 55 food items | Frequency of consumption recalculated into Mediterranean Diet Serving Score (MDSS) | Not specified | Minor psychiatric disorders and psychological distress | General Health Questionnaire-30 (GHQ-30) |

| [47] | Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire with 27 food items | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) | Short Form 36-Health Survey (SF-36), including Mental Health Component (MH) |

| [48] | Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire with 147 food items and 14 items related to local spices and vegetables | Frequency of consumption converted to g/day | Fruits including juices | Depression, anxiety and stress | The Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (DASS, 21-items) |

| [49] | Questions about fruit and vegetable consumption on a previous day | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including canned, dried, fruit juices Vegetables including salads | Psychological well-being | 17-items from the Control, Autonomy, Satisfaction, Pleasure Scale (CASP-17) |

| [50] | Questions about number of days a week when fruit and vegetables are consumed, and consumption on a typical day when they are consumed | Frequency of consumption for raw and processed ones | Fruit including canned Vegetables including canned |

|

|

| [51] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a previous day | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including fruit juices Vegetables including vegetable juices | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [52] | Nutritional questionnaire to assess intake of products for Mediterranean Diet adherence score (MeDi) and Index of Diet Quality (IDQ) | Frequency of consumption | 100% juice as a separate group Vegetables including salads | Perceived happiness | Visual Analog Scale of Happiness (0–100 mm) |

| [53] | Not specified | Frequency of consumption recalculated into Mediterranean Diet Score | Not specified | Depressive symptoms | Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) |

| [54] | Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire with 106 food items | Total fruit and total vegetables intake | Fruit including juices, dried and herbs Vegetables including salads |

|

|

| [55] | Question about eating 5 portions of fruit and vegetables daily during last weeks | 5-point Likert scale for following recommendation | Not specified |

|

|

| [56] | Two items from the National Cancer Institute Quick Food Scan | Frequency of consumption | Fruit including 100% pure juices Vegetables including 100% pure juices | Health-Related Self-Efficacy | Question: “Overall, how confident are you about your ability to take good care of your health?” using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) completely confident to (5) not at all confident |

| [57] | Question about fruit consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Self-reported depression status |

|

| [58] | Validated questions about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including canned Vegetables including salads | Psychological distress | 10-items Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) |

| [59] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Not specified |

|

|

| [60] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption, intake | Fruit including juices | Clinically-relevant levels of depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) |

| [61] | Either semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire with 90 food items (CoLaus/PsyCoLauS), or question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day (SHS) | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including juices Vegetables including salads and juices | Depression | Either semi-structured Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) (CoLaus/PsyCoLauS), or Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (SHS) |

| [62] | The National Cancer Institute (NCI) All Day Fruit and Vegetable Screener | Portion size, frequency of consumption | Vegetables including salads and vegetable soups |

|

|

| [63] | WHO STEPS Instrument | Number of portions | Not specified | Depressive symptoms (including major depressive syndrome) | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) |

| [64] | Validated semi-quantitative questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [65] | Questions about number of days a week when fruit and vegetables are consumed, and consumption on a typical day when they are consumed | Frequency of consumption | Fruit including canned and juices Vegetables including canned and juices | Happiness score | Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ) |

| [66] | Questions about number of days a week when fruit and vegetables are consumed, and consumption on a typical day when they are consumed | Frequency of consumption | Fruit including canned and dried Vegetables including canned | Self-reported life satisfaction |

|

| [67] | Question about fruit and vegetable included to diet at least monthly; Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depression, anxiety and stress | The Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (DASS, 21-items) |

| [68] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a present day | Frequency of consumption | Juices, dried fruits and vegetables excluded |

|

|

| [69] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Juices excluded |

|

|

| [70] | 6-items food frequency screener | Frequency of consumption | Fruit juices and green salad included in the screener as a separate question | Quality of life | Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (including self-reported mental health, days of poor mental health in the past month, days of limited activities because of poor physical/mental health in the past month) |

| [71] | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization food frequency questionnaire (CSIRO FFQ) | Frequency of consumption | Fruit/vegetables excluding juices | Stress | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)—Stress subscale |

| [72] | Food frequency questionnaire including questions about number of days a week when fruit and vegetables are consumed, and consumption on a typical day when they are consumed | Frequency of consumption, following recommendations | Fruits including juices Vegetables including salads and juices | Psychological distress | 5-items Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) |

| [73] | Food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Vegetables including salads |

|

|

| [74] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Vegetables including salads and potatoes | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [75] | 1998 Block Food Frequency Questionnaire for Adults | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depression | The Beck Depression Inventory (21-items); Current use of antidepressants; Self-reported history of treatment for depression |

| [37] | Three 24-h dietary recalls | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including canned, dried, juices Vegetables including juices | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [76] | Semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire with 127 food items | Intake recalculated into the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI), including among others component of fruits and of vegetables | Not specified | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10); Self-reported use of antidepressants |

| [38] | Food frequency questionnaire with 63 food items | Frequency of consumption | Fruit including canned | Psychological distress | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) |

| [77] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Juices excluded |

|

|

| [78] | 24-h dietary recall; Question about frequency of consumption | Number of portions, frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depression | Question about any recent illness (medical conditions during previous 2 weeks) or long-term illness (lasted at least 6 months), screened for depression, based on ICD-10 |

| [79] | Brief self-administered Diet History Questionnaire (BDHQ) with 75 food items | Frequency of consumption | Tomato products including tomato ketchup, stewed tomato, or tomato stew | Depressive symptoms | 30-items Japanese version of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) |

| [80] | Food frequency questionnaire with 49 food items | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Psychologic stress | General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) |

| [81] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day | Frequency of consumption | Juices and dried fruits excluded | Negative and positive affects | Questions about 9 negative (depressed, sad, unhappy, anxious, nervous, tense, angry, hostile, short-tempered) and 9 positive affects (calm, content, relaxed, cheerful, happy, pleased, energetic, enthusiastic, excited) |

| [82] | Not specified | Frequency of consumption | Fruit including orange juice | Depending on the study:

| Depending on the study:

|

| [83] | 3-day dietary record; Validated food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including juices and nectars | Depression | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale, Hamilton Depression Scale (Ham-D), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) |

| [84] | 1998 Block Food Frequency Questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depression; Self-reported physical health | Duke Depression Evaluation Schedule (sections of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Diagnostic Interview Schedule which assesses depression, as well as items on self-reported physical health) |

| [85] | Question about fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical week | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depressive symptoms (interpreted as having a risk of depression) | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [36] | Chinese Food Frequency Questionnaire-Short Form (Short C-FFQ) | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Quality of life | Taiwanese version of the Short Form 36-Health Survey (SF-36) |

| [39] | NCI Fruit and Vegetable screener | Frequency of consumption of 9 categories of fruits and vegetables | Fruit and vegetables (including fruit, fruit juices, salad, beans, French fries, other potatoes, tomato sauce, vegetable soups and other vegetables) | Quality of life | SF-12 Health Survey |

| [86] | 132-item food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Mayonnaise salads excluded from vegetables | Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) |

| [87] | Semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Depressive symptoms | Shortened version of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) |

| [88] | Qualitative 60-items food frequency questionnaire; 24-h dietary recall | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including juices | Attempted suicide | Simple question (“Have you ever attempted suicide?”), according to the standardized criteria established in the Diagnostic Interview Schedule |

| [89] | Food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Vegetables including salads |

|

|

| [90] | Food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Not specified | Self-esteem | Harter Self-Perception Profile for Adults (SPPA) |

| [91] | Cross-check dietary history method | Frequency of consumption, intake | Not specified | Dispositional optimism | 4-item questionnaire—“I still expect much from life,” “I do not look forward to what lies ahead for me in the years to come,” “My days seem to be passing by slowly,” and “I am still full of plans” |

| [92] | Food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including juices |

|

|

| [93] | Food frequency questionnaire with 32 food items | Frequency of consumption | Vegetables including salads | Dispositional optimism | Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) |

| [94] | Food frequency inventory | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including juices Vegetables including salads | Mental health status |

|

| [95] | Food frequency questionnaire | Frequency of consumption | Fruits including dried, canned, pure juices Vegetables including salads, potatoes (not chips) | Anxiety, depression | General Health Questionnaire-30 (GHQ-30) |

| Ref. | Findings | Quality * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Conclusion | ||

| [40] | Women with high stress consumed significantly less fruits (p = 0.01) and vegetables (p = 0.02) than women with low stress, with effect sizes of d = 0.24 and 0.25, respectively, for the between-group differences. | Nutrition counselling on increasing fruit and vegetable intakes may consider targeting women who are black or younger or who report high stress, respectively. | 5 |

| [41] | After adjustment for confounding variables, participants in the highest quartile of the fruits consumption and vegetables consumption had lower prevalence ratio (PR) for depressive symptoms (PR = 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.603–0.974, p = 0.042; PR = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.612–0.977, p = 0.045) than those in the lowest quartile. Those in the highest quartile of total vegetables and fruits consumption had also a lower PR of depressive symptoms (PR = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.503–0.806, p = 0.037) than did those in the lowest quartile. | Higher consumption of vegetables and fruits is significantly associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms. | 5 |

| [42] | Frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables is associated with improved health outcomes, including mental health. | Frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables contributes to slower disablement processes and might be an easily implementable way to improve the overall health of older adults. | 6 |

| [43] | Fruit and vegetable consumption predicted an increased cognitive performance in older adults including improved verbal recall, improved delayed verbal recall, improved digit span test performance and improved verbal fluency; the effect of fruit consumption was much stronger than the effect of vegetable consumption. Regarding mental health, fruit consumption was significantly associated with better subjective quality of life and less depressive symptoms; vegetable consumption, however, did not significantly relate to mental health. | Consumption of fruits is associated with both improved cognitive and mental health in older adults from non-Western developing countries, and consumption of vegetables is associated with improved cognitive health only. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption might be one easy and cost-effective way to improve the overall health and quality of life of older adults in non-Western developing countries. | 5 |

| [44] | Consumption of vegetables and fruits in the last 3 days was less likely to be associated with depression (OR 0.11; 95% CI: 0.02–0.45) and subsyndromal depression (OR 0.10; CI 95%: 0.03–0.39). | Findings support the importance for a healthy consumption of vegetables and fruits for the older adult population in Singapore. | 5 |

| [45] | Fixed effects regressions show that mental well-being (GHQ-12) responds in a dose-response fashion to increases in both the quantity and the frequency of fruit and vegetables consumed. This relationship is robust to the use of subjective well-being (life satisfaction) instead of mental well-being. Increasing one’s consumption of fruit and vegetables by one portion (on a day where at least one portion is consumed) leads to a 0.133-unit increase in mental well-being (p < 0.01). | Persuading people to consume more fruits and vegetables may not only benefit their physical health in the long-run, but also their mental well-being in the short-run. | 6 |

| [35] | Results of generalized estimating equations predicting mental-health-related quality of life indicated that more frequent fruit consumption (p = 0.485) was not, but more frequent vegetable consumption (p = 0.027) was in the fully adjusted model associated with greater mental health-related quality of life. Fruit and vegetable consumption (p = 0.033) was associated with greater mental-health-related quality of life only in the unadjusted model. More frequent fruit (p = 0.566 and p = 0.751, respectively), vegetable (p = 0.173 and p = 0.399), and fruit and vegetable consumption (p = 0.252 and p = 0.634, respectively) did not significantly reduce the risk of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. | The study did not find evidence that more frequent fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with mental-health-related quality of life, depression, and anxiety. However, more frequent vegetable consumption was associated with greater mental-health-related quality of life. | 5 |

| [46] | Inverse association was found between mental distress and higher intake of fruits (β = −0.64, 95% CI: −0.89 to −0.39; p < 0.001), vegetables (β = − 0.39, 95% CI: −0.65 to −0.13; p < 0.003). | Study suggests beneficial association of Mediterranean diet and its elements (including fruit and vegetables intake) and overall mental health, offering important implications for public health provisions. | 5 |

| [47] | After adjusting for potential confounders such as age, body-mass-index (BMI), parity, educational status, occupation, marital status, household hunger scale and household asset index, there was an increasing trend across terciles of vegetable intake in the past month for the HR-QoL (p = 0.0003), mental health (MH) (p = 0.001) domain of the SF-36 and role emotional (p < 0.0001) domain of the SF-36. The multivariate model results a significant increasing trend in the adjusted mean scores of the HR-QoL (p = 0.04), MH (p = 0.001) as well as 4 subscales of the SF-36 [role-physical (p = 0.02), role-emotional (p = 0.05), emotional well-being (p = 0.002) and vitality (p < 0.0001)] across terciles of the vegetable variety score. | Results suggest a potential beneficial role of high vegetable intake and consumption of more varied vegetables on HR-QoL. | 3 |

| [48] | After adjustment for confounding variables, the participants in the lower quartiles of total fruit and vegetables, total vegetables, total fruits, citrus, other fruits and green leafy vegetables intake were more likely to experience depression compared to those in the higher quartiles (p < 0.03). | Lower intake of total fruit and vegetables and some of its specific subgroups might be associated with depression. The findings support encouragement of fruit and vegetables consumption as part of a healthy diet and highlight the importance of fruit and vegetables consumption and a number of their subgroups in mitigating the chance of depression. | 7 |

| [49] | Mixed linear models showed that higher baseline levels of psychological well-being were associated with more fruit and vegetable consumption at baseline (β = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.02–0.08) and that fruit and vegetable consumption declined across time (β = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.02–0.004). Psychological well-being interacted significantly with time such that individuals with higher baseline psychological well-being had slower declines in fruit and vegetable consumption (β = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.01–0.02). Among individuals who initially met recommendations to consume 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables, higher baseline psychological well-being was associated with 11% reduced risk of falling below recommended levels during follow-up (hazard ratio = 0.89; 95% CI: 0.83–0.95). | Psychological well-being may be a precursor to healthy behaviors such as eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables. Analyses also considered the likelihood of reverse causality. | 6 |

| [50] | Controlling for covariates, raw fruit and vegetable intake (FVI) predicted reduced depressive symptoms and higher positive mood, life satisfaction, and flourishing; processed FVI only predicted higher positive mood. The top 10 raw foods related to better mental health were carrots, bananas, apples, dark leafy greens like spinach, grapefruit, lettuce, citrus fruits, fresh berries, cucumber, and kiwifruit. | Raw FVI, but not processed FVI, significantly predicted higher mental health outcomes when controlling for the covariates. Applications include recommending the consumption of raw fruits and vegetables to maximize mental health benefits. | 2 |

| [51] | Individuals who were depressed at both times points had the highest proportion who failed to consume any fruit (31%) or vegetables (42%) on the previous day. Fruit and vegetable consumption did not predict of adult depression in fully adjusted models. | Cross sectional associations existed for diet and adolescent depression only. For adult depression association was subsequently attenuated on adjustment for other relevant factors. | 5 |

| [52] | Happiness was linearly associated with total fruit and vegetable intakes (p = 0.002). | Maintaining good nutrition and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption may be important for psychological health of older people. | 4 |

| [53] | Subjects who reported to consume a greater amount of fruit were associated with a lower risk of depression (OR 0.46; 95% CI: 0.26–0.84, p = 0.011) after adjustment for many possible confounders. Similar results were obtained for women, while no statistically significant differences emerged for men. | Diet rich in olive oil and fruit, characteristics of Mediterranean diet, may protect against the development of depressive symptoms in older age. | 4 |

| [54] | Women in the top quintile of fruit intake, compared with those in the bottom quintile, had 57%, 50%, and 60% lower odds of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. Consumption of vegetables was significantly associated with lower odds of depression (OR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.46–0.93) in women and lower odds of anxiety (OR 0.43; 95% CI: 0.22–0.87) in men. After adjustment for potential confounders, women in the highest quintile of fruit and vegetables intake, compared with those in the bottom quintile, had significantly lower odds of depression (OR 0.55; 95% CI: 0.37–0.80) and psychological distress (OR 0.60; 95% CI: 0.40–0.90). High intake of total fruit and vegetables was associated with lower odds of psychological distress (OR 0.42; 95% CI: 0.21–0.81) in men. | There was a significant inverse associations between high intake of fruit with depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in Iranian women. High consumption of vegetables was also associated with lower risk of depression and anxiety, in women and men. In addition, high intake of total fruit and vegetable was associated with lower odds of depression and psychological distress in women and men. | 6 |

| [55] | Vegetable intake were associated with increased sleep quality, which in turn was associated with increased overall quality of life (p < 0.05). | Results suggest possible relationships among the multiple health behaviors and their associations with overall well-being. | 3 |

| [56] | Perceived ambiguity and cancer fatalism were negatively associated with fruit and vegetables consumption (p < 0.001) whereas health-related self-efficacy was positively associated with fruit and vegetables consumption (b = 0.34, p < 0.001). | Individual choice influences fruit and vegetables consumption, but external control beliefs, as measured by perceived ambiguity of cancer prevention recommendations and cancer fatalism, and internal control beliefs, as measured by health-related self-efficacy, may be important inputs to these decisions. | 7 |

| [57] | In India, those who consumed less than five servings of vegetables were respectively 41% (AOR = 1.41; 95% CI: 0.60–3.33) and 57% (AOR = 1.57; 95% CI: 0.93–2.64) more likely to report severe-extreme and mild-moderate depression during past 30 days compared to those who consumed five servings a day. Regarding fruit consumption, compared to those who consumed five servings a day, the odds of severe-extreme and mild-moderate self-reported depression were respectively 3.5 times (AOR = 3.48; 95% CI: 1.216–10.01) and 45% (AOR = 1.44; 95% CI: 0.89–2.32) higher in Bangladesh, and 2.9 times (AOR = 2.92; 95% CI: 1.12–7.64) and 42% higher (AOR = 1.41; 95% CI: 0.89–2.24) in Nepal compared to those who consumed less than five servings a day during last 30 days. | Daily intake of less than five servings of fruit and vegetables was associated with higher odds of depression. Nutrition programs aimed at promoting fruit and vegetables consumption might prove beneficial to reduce the prevalence of depression in south Asian population. | 5 |

| [58] | Baseline fruit and vegetable consumption considered separately or combined, was associated with a lower prevalence of psychological distress even after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle risk factors. Baseline fruit and vegetable consumption, measured separately or combined, was associated with a lower incidence of psychological distress in minimally adjusted models. Most of these associations remained significant at medium levels of intake but were no longer significant at the highest intake levels in fully adjusted models. | Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption may help reduce psychological distress in middle-aged and older adults. | 8 |

| [59] | Results indicate that the amount of fruit and vegetable consumption was positively associated with happiness and inversely associated with depression. Happiness increased with any increase to fruit and vegetable consumption, the strongest increase in the adjusted analysis was with 6 servings of fruit and vegetables, with a coefficient of 0.41. Depressive symptoms decreased with any increase to fruit and vegetable consumption, the strongest decrease in the adjusted analysis was with 6 servings of fruit and vegetables, with a coefficient of −1.04. | Healthier behavior patterns of fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with higher happiness and lower depression scores among university students across 28 countries. | 5 |

| [60] | The intake of green vegetables was associated with lower odds of having clinically-relevant levels of depressive symptoms (OR 0.192, p = 0.016). | Green vegetables, total FVI showed protective effects regarding clinically-relevant levels of depressive symptoms. | 5 |

| [61] | For depression subtypes, statistically significantly positive associations of vegetable consumption and adherence to the 5-a-day recommendation with current unspecified and current melancholic major depressive disorder were found (OR 2.09; 95% CI: 1.08–4.06 and OR 2.51; 95% CI: 1.21–5.21, respectively; multivariable adjusted for demographic and other dietary factors) | There is no consistent association between adherence to dietary recommendations and major depressive disorder or subtypes of depression. | 5 |

| [62] | Mean positive affect increased linearly as a function of number of daily servings of fruits and vegetables; the pattern of this relationship did not differ significantly for males and females. This association remained statistically significant after controlling for demographic variables (age, sex, and parent education levels); other diet variables (consumption of sugar containing beverages, coffee or tea, and fat); and other health behaviors (exercise, sleep quality and smoking). Life satisfaction and negative affect were not significantly related to fruit and vegetable consumption. | There is an association of fruits and vegetable consumption with well-being. | 3 |

| [63] | Participants in the lowest tertile of fruits and/or vegetables consumption had greater prevalence of depressive symptoms (PR = 1.88; 95% CI: 1.39–2.55) than those in the highest tertile. This association was stronger with fruits (PR = 1.92; 95% CI: 1.46–2.53) than vegetables (PR = 1.42; 95% CI: 1.05–1.93) alone. | An inverse relationship between consumption of fruits and/or vegetables and depressive symptoms was concluded. There is a need to implement strategies to promote better diet patterns with potential impact on mental health. | 6 |

| [64] | High fruit or high vegetable consumption alone (>5 times/week) was not significantly associated with new depressive symptoms. Combining high fruit (OR 0.61; 95% CI: 0.41–0.89), vegetable (OR 0.49; 95% CI: 0.26–0.93) or fruit and vegetable (OR 0.39; 95% CI: 0.20–0.77) consumption with high leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) reduced the likelihood of developing subsequent new depressive symptoms beyond LPTA alone. | The simultaneous presence of several good lifestyle habits (high fruit and vegetable consumption with high leisure-time physical activity) increases the beneficial effect of reducing the risk of developing depressive symptoms in older adults. Thus, older adults are encouraged to have as many good lifestyle habits as possible to reduce the risk of depressive symptoms. | 7 |

| [65] | Measure of happiness was positively associated with the amount of fruit and vegetable consumption (p = 0.02, and 0.045 respectively). Students who ate breakfast every day, more than 8 servings of fruit and vegetables daily, and had 3 meals in addition to 1–2 snacks per day had the highest happiness score. | Healthier behavior pattern (including fruit and vegetable consumption) was associated with higher happiness scores among medical students. | 3 |

| [66] | Increased fruit and vegetable consumption was predictive of increased happiness, life satisfaction, and well-being. They were up to 0.24 life-satisfaction points (for an increase of 8 portions a day), which is equal in size to the psychological gain of moving from unemployment to employment. Improvements occurred within 24 months. | Eating certain foods is a form of investment in future happiness and well-being. The implications of fruit and vegetable consumption are estimated to be substantial and to operate within the space of 2 years. | 5 |

| [67] | In males, anxiety was correlated with lower daily intakes of fruits and vegetables (r = −0.216, p = 0.013). | A strict plant-based diet does not appear to negatively impact mood. | 2 |

| [68] | Fruit and vegetables consumption predicted greater eudaemonic well-being, curiosity, and creativity at the between- and within-person levels. Young adults who ate more fruit and vegetables reported higher average eudaemonic well-being, more intense feelings of curiosity, and greater creativity compared with young adults who ate less fruit and vegetables. On days when young adults ate more fruit and vegetables, they reported greater eudaemonic well-being, curiosity, and creativity compared with days when they ate less fruit and vegetables. Fruit and vegetables consumption also predicted higher positive effects, which mostly did not account for the associations between fruit and vegetables and the other well-being variables. Lagged data analyses showed no carry-over effects of fruit and vegetables consumption onto next-day well-being (or vice versa). | Fruit and vegetables consumption may be related to a broader range of well-being states than signal human flourishing in early adulthood. | 4 |

| [69] | Fruit and vegetable consumption at each cycle was inversely associated with next-cycle depression (β = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.05 to −0.01, p < 0.01) and psychological distress (β = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.05 to −0.02, p < 0.0001). However, once models were adjusted for other health-related factors, these associations were attenuated (β = −0.01, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.02, p = 0.55; β = −0.00, 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.02, p = 0.78 for models predicting depression and distress, respectively). | Findings suggest that relations between fruit and vegetable intake, other health-related behaviors and depression are complex. | 8 |

| [70] | Significant associations were found between vegetables intake (green salad) and physical health days for Hispanics and fruit and vegetables intake (green salad, fruit, and fruit juice) and self-reported health for Chinese. | There is a need to promote healthy living behaviors among aging NYC racial/ethnic populations | 5 |

| [71] | Men who experienced mild to moderate levels of stress were less likely to consume vegetables and fruit (p < 0.05) compared with their unstressed counterparts. The trend analysis results indicated significant dose–response patterns in the relationship between stress level and consumption of vegetables and fruit (negative trend) (adjusted OR 0.50; 95% CI: 0.48–0.87; p < 0.05). For female students significant dose–response trend was found in the relationship between stress levels and the consumption of vegetables and fruit (both negative trends) (p < 0.01). | There is a difference in food selection patterns between stressed male and female students, with stress being a more significant predictor of unhealthy food selection among male students. | 4 |

| [72] | Consumers fulfilling the 5-a-day recommendation had lower odds of being highly or moderately distressed than individuals consuming less fruit and vegetables (moderate vs. low distress: OR 0.82; 95% CI: 0.69–0.97; high vs. low distress: OR 0.55; 95% CI: 0.41–0.75). | Daily intake of 5 servings of fruit and vegetable was associated with lower psychological distress. | 5 |

| [73] | For females fresh fruits (−0.085; p < 0.001), salad/raw vegetables (−0.048; p < 0.001), cooked vegetables (−0.061; p < 0.001) intake were respectively negatively associated with Perceived Stress Score. For both sexes, consuming fresh fruits (−0.111; p < 0.001 for females; −0.074; p = 0.047 for males), salads (−0.071; p < 0.001 for females; −0.091; p = 0.014 for males), cooked vegetables (−0.072; p < 0.001 for females; −0.089; p = 0.017 for males) was significantly negatively associated with perceived stress and depressive symptoms scores. | The associations between consuming ‘healthy’ foods and lower depressive symptoms and perceived stress among male and female students in three UK countries suggest that interventions to reduce depressive symptoms and stress among students could also result in the consumption of healthier foods and/or vice versa. | 5 |

| [74] | Analysis showed reduced odds of depressive symptoms OR 0.86 (95% CI: 0.79–0.95, p = 0.001) among women who ate ⩾ 2 of fruit/day and OR 0.79 (95% CI: 0.67–0.93, p = 0.007) among women who ate ⩾ 5 vegetables/day, even after adjustment for several factors including smoking, alcohol, body mass index, physical activity, marital status, education, energy, fish intake, and comorbidities. | Increasing fruit consumption may be one important factor for reducing both the prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-age women. | 6 |

| [75] | Higher Beck Depression Inventory scores correlated with lower fruit and vegetable consumption (r = −0.20, p = 0.006). Women reporting a history of treatment for depression showed lower levels of fruit and vegetable consumption (mean daily servings = 2.0 [1.3] vs. 2.5 [1.3], respectively, p = 0.03). Participants reporting current antidepressant use (versus non-users) did not differ on dietary habits. | Fruit and vegetable consumption partially mediated associations between depression and time to cardiovascular disease events. | 6 |

| [37] | Depressive symptoms were not associated with fruit and vegetables intake (p > 0.05). | Future studies should explore the mechanisms linking the identified associations between depressive symptoms and dietary intake, such as the role of emotional eating. | 6 |

| [76] | After adjustment for potential confounders, the AHEI score was inversely associated with recurrent depressive symptoms in a dose-response fashion in women (p = 0.001; for 1 SD in AHEI score; OR 0.59; 95% CI: 0.47–0.75) but not in men, while among its components vegetable and fruit intake were significant. | Poor diet may be a risk factor for future depression in women. | 6 |

| [38] | No significant associations were found between prevalence of distress and vegetable and/or fruit intake (p = 0.911 for males; p = 0.908 for females). | Psychological distress is not associated with reduced intake fruit and vegetables. | 5 |

| [77] | Greater fruit and vegetable intake was significantly associated with lower odds of depression (OR 0.72; 95% CI: 0.71–0.75)—for all 5 waves. Perceived poor mental health status and previous diagnosis of a mood disorder and anxiety disorder also demonstrated statistically significant inverse associations with fruit and vegetable intake (all p < 0.05). In the first wave, greater fruit and vegetable intake was significantly associated with lower odds of depression (OR 0.85; 95% CI: 0.78–0.92). A combined estimate of all 5 waves demonstrated similar results (OR 0.72; 95% CI: 0.71–0.75). Relative to those with the lowest fruit and vegetable intake, those with the greatest fruit and vegetable intake also had significantly lower odds of suffering from distress (OR 0.87; 95% CI: 0.78–0.98). These results were consistent across other waves. Perceived poor mental health status and previous diagnosis of a mood disorder and anxiety disorder also demonstrated statistically significant inverse associations with fruit and vegetable intake (all p < 0.05). | Findings suggest a potentially important role of a healthy diet in the prevention of depression and anxiety. | 5 |

| [78] | There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) of intake of vegetable products and dishes in women with depression compared with women without depression. The regression model indicated among others that increased intakes per kilojoule of vegetables (p = 0.015) are associated with lower odds of having depression. | The results confirm a collective effect of diet on mood. | 6 |

| [79] | After adjustments for potentially confounding factors, the odds ratios of having mild and severe depressive symptoms by increasing levels of tomatoes/tomato products were 1.00, 0.54, and 0.48 (p <0.01). No relationship was observed between intake of other kinds of vegetables and depressive symptoms. | Tomato-rich diet is independently related to lower prevalence of depressive symptoms and may have a beneficial effect on the prevention of depressive symptoms. | 6 |

| [80] | Dietary intake of inter alia fruits and vegetables was significantly higher in the low-stress group than in high-stress group. There was an inverse association between stress level and intake of fruits and vegetables (OR 0.83; 95% CI: 0.76–0.90). | The results showed a significant positive association between dietary intake and stress. There must be a special attention to dietary intake in stress management program of high-stress individuals, and in dietary recommendations, psychologic aspects should be considered. | 5 |

| [81] | Analyses of same-day within-person associations revealed that on days when young adults experienced greater positive affect, they reported eating more servings of fruit (p = 0.002) and vegetables (p < 0.001). Results of lagged analysis showed that fruits and vegetables predicted improvements in positive affect the next day, suggesting that healthy foods were driving affective experiences and not vice versa. Meaningful changes in positive affect were observed with the daily consumption of approximately 7–8 servings of fruit or vegetables. | Eating fruit and vegetables may promote emotional well-being among healthy young adults. | 3 |

| [82] | In cross-sectional data, happiness and mental health rise in an approximately dose–response way with the number of daily portions of fruit and vegetables. Well-being peaks at approximately 7 portions per day. It was documented for seven measures of well-being (life satisfaction, WEMWBS mental well-being, GHQ mental disorders, self-reported health, happiness, nervousness, and feeling low). The pattern is robust to adjustment for a large number of other demographic, social and economic variables. | There is a positive association between eating fruit and vegetables and having high mental well-being. | 4 |

| [83] | Compared to the regional nutrition survey data, a greater proportion of study participants (the members of Mood Disorders Association of British Columbia) consumed fewer of the recommended servings of vegetables and fruits (p < 0.05). | The adults with mood disorders could benefit from nutritional interventions to improve diet quality. | 4 |

| [84] | Fruit and vegetable consumption was lower in depressed individuals, than in comparison individuals, that remained significant in multivariable models. | These results may indicate the importance of components of fruits and vegetables, including antioxidants, rather than dietary supplements. | 6 |