Face-to-Face and Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions to Enhance Cognitive Reserve and Reduce Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: A Review of Completed and Prospective Studies

Abstract

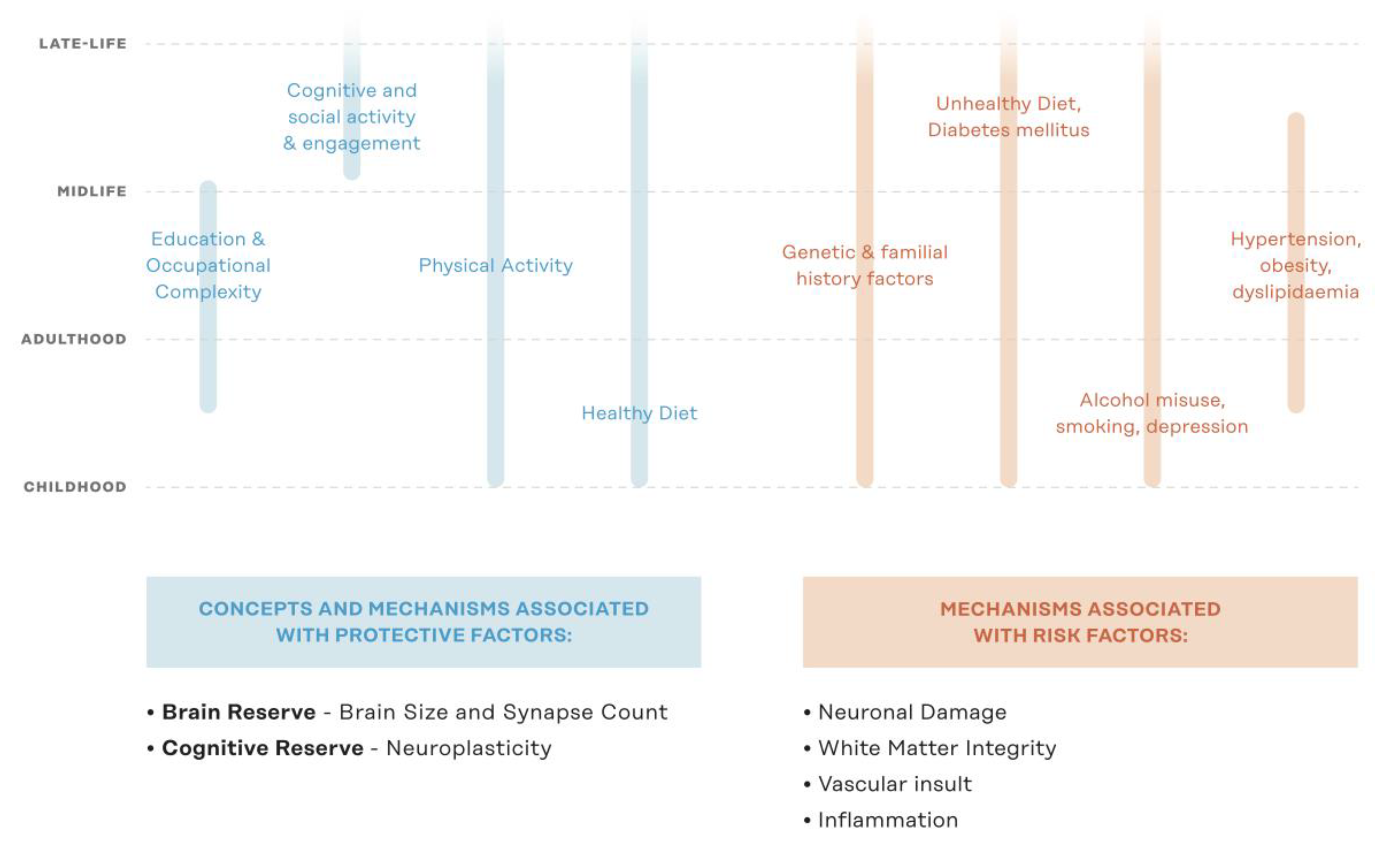

1. Introduction

From Single-Domain to Multi-Domain Interventions

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Completed Face-to-Face (FTF) Multidomain Interventions

3.1.1. Prevention of Dementia by Intensive Vascular Care (preDIVA)

3.1.2. The Multidomain Alzheimer’s Prevention Trial (MAPT)

3.1.3. The Finish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER)

3.1.4. The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT; SPRINT-MIND)

3.2. On-Going and Prospective Face-to-Face (FTF) Multidomain Interventions

3.2.1. Age Well.de

3.2.2. Systematic Multi-Domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT)

3.2.3. The Multimodal Preventive Trial for Alzheimer′s Disease (MIND-ADmini)

3.2.4. The Multiple Nonpharmacological Interventions Study (EmuNI)

3.2.5. Taiwan Multidomain Intervention Efficacy Study—National Taiwan University Hospital

3.2.6. The Body, Brain, Life—General Practice Lifestyle Modification Program Study (BBL-GPLMP)

3.3. On-Going and Prospective World Wide Fingers Studies

3.4. On-Going and Prospective Multidomain Interventions

3.4.1. The Maintain Your Brain Study (MYB)

3.4.2. The Digital Cognitive Multidomain Alzheimer’s Risk Velocity Study (DC-MARVEL)

3.4.3. The Body, Brain, Life for Cognitive Decline Study (BBL-CD)

3.4.4. Healthy Ageing Through Internet Counselling in the Elderly (HATICE)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.; Wu, Y.; Prina, M. World Alzheimer Report 2015—The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J.; James, B.; Johnson, T.; Marin, A.; Weuve, J. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Knapp, M.; Guerchet, M.; Karagiannidou, M. World Alzheimer Report 2016: Improving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia: Coverage, Quality and Costs Now and in the Future. Available online: http://www.alz.co.uk/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Wortmann, M. Dementia: A global health priority—Highlights from an ADI and World Health Organization report. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2012, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Aisen, P.S.; DuBois, B.; Frölich, L.; Jack, C.R.; Jones, R.W.; Morris, J.C.; Raskin, J.; Dowsett, S.A.; Scheltens, P. Drug development in Alzheimer’s disease: The path to 2025. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2016, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, S.; Matthews, F.E.; Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K.; Brayne, C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Ambrose, T.; Nagamatsu, L.S.; Graf, P.; Beattie, B.L.; Ashe, M.C.; Handy, T.C. Resistance training and executive functions: A 12-month randomized controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, A.; Rocca, W.A.; Tzourio, C. Vascular risk factors and dementia. Neurology 2009, 72, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampit, A.; Hallock, H.; Valenzuela, M. Computerized cognitive training in cognitively healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of effect modifiers. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangour, A.D.; Allen, E.; Elbourne, D.; Fasey, N.; Fletcher, A.E.; Hardy, P.; Holder, G.E.; Knight, R.; Letley, L.; Richards, M.; et al. Effect of 2-y n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on cognitive function in older people: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sink, K.M.; Espeland, M.A.; Castro, C.M.; Church, T.; Cohen, R.; Dodson, J.A.; Guralnik, J.; Hendrie, H.C.; Jennings, J.; Katula, J.; et al. Effect of a 24-Month Physical Activity Intervention vs Health Education on Cognitive Outcomes in Sedentary Older Adults: The LIFE Randomized Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 314, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Berch, D.B.; Helmers, K.F.; Jobe, J.B.; Leveck, M.D.; Marsiske, M.; Morris, J.N.; Rebok, G.W.; Smith, D.M.; Tennstedt, S.L.; et al. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 288, 2271–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unverzagt, F.W.; Guey, L.T.; Jones, R.N.; Marsiske, M.; King, J.W.; Wadley, V.G.; Crowe, M.; Rebok, G.W.; Tennstedt, S.L. ACTIVE cognitive training and rates of incident dementia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2012, 18, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Inouye, S.K.; Bogardus, S.T.; Charpentier, P.A.; Leo-Summers, L.; Acampora, D.; Holford, T.R.; Cooney, L.M. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T.G.; Tulebaev, S.R.; Inouye, S.K. Delirium in elderly adults: Diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2009, 5, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellas, B.; Carrie, I.; Gillette-Guyonnet, S.; Touchon, J.; Dantoine, T.; Dartigues, J.F.; Cuffi, M.N.; Bordes, S.; Gasnier, Y.; Robert, P.; et al. Mapt Study: A Multidomain Approach for Preventing Alzheimer’s DISEASE: Design and Baseline Data. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2014, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER): Study design and progress. Alzheimers Dement. 2013, 9, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, E.; Van den Heuvel, E.; Moll van Charante, E.P.; Achthoven, L.; Vermeulen, M.; Bindels, P.J.; Van Gool, W.A. Prevention of dementia by intensive vascular care (PreDIVA): A cluster-randomized trial in progress. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2009, 23, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinsky, F.D.; Vander Weg, M.W.; Howren, M.B.; Jones, M.P.; Dotson, M.M. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive training using a visual speed of processing intervention in middle aged and older adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.L.; Tennstedt, S.L.; Marsiske, M.; Ball, K.; Elias, J.; Koepke, K.M.; Morris, J.N.; Rebok, G.W.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Stoddard, A.M.; et al. Long-term effects of cognitive training on everyday functional outcomes in older adults. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 296, 2805–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebok, G.W.; Ball, K.; Guey, L.T.; Jones, R.N.; Kim, H.-Y.; King, J.W.; Marsiske, M.; Morris, J.N.; Tennstedt, S.L.; Unverzagt, F.W.; et al. Ten-year effects of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Can lifestyle changes prevent cognitive impairment? Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialasche, F.; Xu, W.; Kivipelto, M. Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease: Intervention Studies. In Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, H.; Lee, S.; Doi, T.; Bae, S.; Makino, K.; Chiba, I.; Arai, H. Study protocol of the self-monitoring activity program: Effects of activity on incident dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 5, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstey, K.J.; Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Herath, P.; Kim, S.; Burns, R.; Rebok, G.W.; Cherbuin, N. Body brain life: A randomized controlled trial of an online dementia risk reduction intervention in middle-aged adults at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2015, 1, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Charante, E.P.M.; Richard, E.; Eurelings, L.S.; van Dalen, J.-W.; Ligthart, S.A.; van Bussel, E.F.; Hoevenaar-Blom, M.P.; Vermeulen, M.; van Gool, W.A. Effectiveness of a 6-year multidomain vascular care intervention to prevent dementia (preDIVA): A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, S.; Guyonnet, S.; Coley, N.; Cantet, C.; Bonnefoy, M.; Bordes, S.; Bories, L.; Cufi, M.-N.; Dantoine, T.; Dartigues, J.-F.; et al. Effect of long-term omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with or without multidomain intervention on cognitive function in elderly adults with memory complaints (MAPT): A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassine, H.N.; Schneider, L.S. Lessons from the Multidomain Alzheimer Preventive Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kivipelto, M.; Ngandu, T.; Laatikainen, T.; Winblad, B.; Soininen, H.; Tuomilehto, J. Risk score for the prediction of dementia risk in 20 years among middle aged people: A longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindi, S.; Calov, E.; Fokkens, J.; Ngandu, T.; Soininen, H.; Tuomilehto, J.; Kivipelto, M. The CAIDE Dementia Risk Score App: The development of an evidence-based mobile application to predict the risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 1, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecay-Torres, M.; Estanga, A.; Tainta, M.; Izagirre, A.; Garcia-Sebastian, M.; Villanua, J.; Clerigue, M.; Iriondo, A.; Urreta, I.; Arrospide, A.; et al. Increased CAIDE dementia risk, cognition, CSF biomarkers, and vascular burden in healthy adults. Neurology 2018, 91, e217–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Levälahti, E.; Laatikainen, T.; Lindström, J.; Peltonen, M.; Solomon, A.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Hänninen, T.; et al. Recruitment and baseline characteristics of participants in the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER)-a randomized controlled lifestyle trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9345–9360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Minassian, S.L.; Jenkins, L.; Black, R.S.; Koller, M.; Grundman, M. A Neuropsychological Test Battery for Use in Alzheimer Disease Clinical Trials. Arch. Neurol. 2007, 64, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, N.; Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Soininen, H.; Vellas, B.; Richard, E.; Kivipelto, M.; Andrieu, S. HATICE, FINGER, and MAPT/DSA groups Adherence to multidomain interventions for dementia prevention: Data from the FINGER and MAPT trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, T.E.; Levälahti, E.; Ngandu, T.; Solomon, A.; Kivipelto, M.; Kivipelto, M.; Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Laatikainen, T.; Soininen, H.; et al. Health-related quality of life in a multidomain intervention trial to prevent cognitive decline (FINGER). Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 8, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Rizzuto, D.; Fratiglioni, L.; Antikainen, R.; Laatikainen, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Peltonen, M.; Soininen, H.; Strandberg, T.; Tuomilehto, J.; et al. The Effect of a 2-Year Intervention Consisting of Diet, Physical Exercise, Cognitive Training, and Monitoring of Vascular Risk on Chronic Morbidity-the FINGER Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmala, J.; Ngandu, T.; Havulinna, S.; Levälahti, E.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Antikainen, R.; Laatikainen, T.; Pippola, P.; Peltonen, M.; et al. The Effect of Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention on Daily Functioning in Older People. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.; Ngandu, T.; Rusanen, M.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Havulinna, S.; Hänninen, T.; Laatikainen, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Levälahti, E.; et al. Multidomain lifestyle intervention benefits a large elderly population at risk for cognitive decline and dementia regardless of baseline characteristics: The FINGER trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A.; Turunen, H.; Ngandu, T.; Peltonen, M.; Levälahti, E.; Helisalmi, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; et al. Effect of the Apolipoprotein E Genotype on Cognitive Change During a Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention: A Subgroup Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.D.; Pajewski, N.M.; Auchus, A.P.; Bryan, R.N.; Chelune, G.; Cheung, A.K.; Cleveland, M.L.; Coker, L.H.; Crowe, M.G.; Cushman, W.C.; et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 321, 553–561. [Google Scholar]

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright, J.T.; Williamson, J.D.; Whelton, P.K.; Snyder, J.K.; Sink, K.M.; Rocco, M.V.; Reboussin, D.M.; Rahman, M.; Oparil, S.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, W.T.; Sink, K.M.; Foy, C.G.; Berlowitz, D.R.; Cheung, A.K.; Cushman, W.C.; Fine, L.J.; Goff, D.C.; Johnson, K.C.; Killeen, A.A.; et al. The design and rationale of a multicenter clinical trial comparing two strategies for control of systolic blood pressure: The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). Clin. Trials 2014, 11, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrallah, I.M.; Pajewski, N.M.; Auchus, A.P.; Chelune, G.; Cheung, A.K.; Cleveland, M.L.; Coker, L.H.; Crowe, M.G.; Cushman, W.C.; Cutler, J.A.; et al. Association of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control with Cerebral White Matter Lesions. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 322, 524–534. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran, S. Blood Pressure, Brain Volume and White Matter Hyperintensities, and Dementia Risk. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 322, 512–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AgeWell.de—Study Protocol of a Pragmatic Multi-Center Cluster-Randomized Controlled Prevention Trial Against Cognitive Decline in Older Primary Care Patients. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334847150_AgeWellde_-_study_protocol_of_a_pragmatic_multi-center_cluster-randomized_controlled_prevention_trial_against_cognitive_decline_in_older_primary_care_patients (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Yaffe, K.; Barnes, D.E.; Rosenberg, D.; Dublin, S.; Kaup, A.R.; Ludman, E.J.; Vittinghoff, E.; Peltz, C.B.; Renz, A.D.; Adams, K.J.; et al. Systematic Multi-Domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT): Study Protocol. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 70, S207–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; McMaster, M.; Torres, S.; Cox, K.L.; Lautenschlager, N.; Rebok, G.W.; Pond, D.; D’Este, C.; McRae, I.; Cherbuin, N.; et al. Protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of Body Brain Life—General Practice and a Lifestyle Modification Programme to decrease dementia risk exposure in a primary care setting. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Cherbuin, N.; Anstey, K.J. Assessing reliability of short and tick box forms of the ANU-ADRI: Convenient alternatives of a self-report Alzheimer’s disease risk assessment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T.; Eg, J.J.E.; Kivipelto, M.; Ngandu, T.; Soininen, H.; Tuomilehto, J.; Lindström, J.; Solomon, A.; et al. World Wide Fingers will advance dementia prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Fingers. Available online: https://www.alz.org/wwfingers/overview.asp#projects (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Heffernan, M.; Andrews, G.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A.; Valenzuela, M.; Anstey, K.J.; Maeder, A.J.; McNeil, J.; Jorm, L.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Sachdev, P.S.; et al. Maintain Your Brain: Protocol of a 3-Year Randomized Controlled Trial of a Personalized Multi-Modal Digital Health Intervention to Prevent Cognitive Decline Among Community Dwelling 55 to 77 Year Olds. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 70, S221–S237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.C.; Lampit, A.; Boulamatsis, C.; Hallock, H.; Barr, P.; Ginige, J.A.; Brodaty, H.; Chau, T.; Heffernan, M.; Sachdev, P.S.; et al. Design and Development of the Brain Training System for the Digital “Maintain Your Brain” Dementia Prevention Trial. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampit, A.; Valenzuela, M. Pointing the FINGER at multimodal dementia prevention. Lancet 2015, 386, 1625–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, N.; Kumar, S.; Krebs, C.; Glenn, J.M.; Madero, E.N.; Juusola, J.L. A Remote Intervention to Prevent or Delay Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: Design, Recruitment, and Baseline Characteristics of the Virtual Cognitive Health (VC Health) Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e11368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galusha-Glasscock, J.M.; Horton, D.K.; Weiner, M.F.; Cullum, C.M. Video Teleconference Administration of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Tran, J.L.; Moseson, H.; Tai, C.; Glenn, J.M.; Madero, E.N.; Juusola, J.L. The Impact of the Virtual Cognitive Health Program on the Cognition and Mental Health of Older Adults: Pre-Post 12-Month Pilot Study. JMIR Aging 2018, 1, e12031. Available online: https://aging.jmir.org/2018/2/e12031/ (accessed on 23 August 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMaster, M.; Kim, S.; Clare, L.; Torres, S.J.; D’Este, C.; Anstey, K.J. Body, Brain, Life for Cognitive Decline (BBL-CD): Protocol for a multidomain dementia risk reduction randomized controlled trial for subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 2397–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstey, K.J.; Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Herath, P.; Rebok, G.W.; Cherbuin, N. A 12-week multidomain intervention versus active control to reduce risk of Alzheimer’s disease: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, E.; Jongstra, S.; Soininen, H.; Brayne, C.; van Charante, E.P.M.; Meiller, Y.; Ngandu, T. Healthy Ageing Through Internet Counselling in the Elderly: The HATICE randomised controlled trial for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010806. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/6/e010806 (accessed on 22 August 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbera, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Jongstra, S.; Guillemont, J.; Ngandu, T.; Beishuizen, C.; Coley, N.; Brayne, C.; Andrieu, S.; Richard, E.; et al. Designing an Internet-Based Multidomain Intervention for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: The HATICE Trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Albanese, E.; Duggan, C.; Rudan, I.; Langa, K.M.; Carrillo, M.C.; Chan, K.Y.; Joanette, Y.; Prince, M.; Rossor, M.; et al. Research priorities to reduce the global burden of dementia by 2025. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.L.; Morstorf, T.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: Few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Mangialasche, F.; Kivipelto, M. Dementia research priorities-2. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines; WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-4-155054-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lourida, I.; Hannon, E.; Littlejohns, T.J.; Langa, K.M.; Hyppönen, E.; Kuzma, E.; Llewellyn, D.J. Association of Lifestyle and Genetic Risk with Incidence of Dementia. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 322, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangialasche, F.; Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; Fratiglioni, L. Dementia prevention: Current epidemiological evidence and future perspective. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2012, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondell, S.J.; Hammersley-Mather, R.; Veerman, J.L. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.-F.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, X.-C.; Lu, H.; Tan, M.-S.; Yu, J.-T. Dietary Patterns and Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6144–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marioni, R.E.; Proust-Lima, C.; Amieva, H.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H. Social activity, cognitive decline and dementia risk: A 20-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najar, J.; Östling, S.; Gudmundsson, P.; Sundh, V.; Johansson, L.; Kern, S.; Guo, X.; Hällström, T.; Skoog, I. Cognitive and physical activity and dementia: A 44-year longitudinal population study of women. Neurology 2019, 92, e1322–e1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.J.; Zhao, Y. Smoking is associated with an increased risk of dementia: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies with investigation of potential effect modifiers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabia, S.; Fayosse, A.; Dumurgier, J.; Schnitzler, A.; Empana, J.-P.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Dugravot, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Association of ideal cardiovascular health at age 50 with incidence of dementia: 25 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2019, 366, l4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, F.J.; Tinga, L.M.; Dhana, K.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Hofman, A.; Bos, D.; Franco, O.H.; Ikram, M.A. Life Expectancy with and Without Dementia: A Population-Based Study of Dementia Burden and Preventive Potential. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterberger, M.; Fischer, P.; Zehetmayer, S. Incidence of Dementia over Three Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Briggs, R.; Kennelly, S.P.; O’Neill, D. Drug treatments in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, R.; Donohue, M.; Aisen, P. The A4 trial: Anti-amyloid treatment of asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2012, 8, P425–P426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.D.; Supiano, M.A.; Applegate, W.B.; Berlowitz, D.R.; Campbell, R.C.; Chertow, G.M.; Fine, L.J.; Haley, W.E.; Hawfield, A.T.; Ix, J.H.; et al. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged ≥75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 315, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, N.J.; Okereke, O.I.; Vannini, P.; Amariglio, R.E.; Rentz, D.M.; Marshall, G.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Sperling, R.A. Association of Higher Cortical Amyloid Burden with Loneliness in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, E.; Martín-María, N.; De la Torre-Luque, A.; Koyanagi, A.; Vancampfort, D.; Izquierdo, A.; Miret, M. Does loneliness contribute to mild cognitive impairment and dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 52, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Wilson, R.S.; Leurgans, S.E.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old age. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Wahlund, L.-O.; Westman, E. The heterogeneity within Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2018, 10, 3058–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, C.P.; Jacob, K.S. Dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: Different realities mandate tailored solutions. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Paddick, S.-M. Dementia prevention in low-income and middle-income countries: A cautious step forward. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e538–e539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N.; Sommerlad, A.; Huntley, J.; Livingston, G. Population attributable fractions for risk factors for dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: An analysis using cross-sectional survey data. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e596–e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastawrous, A.; Armstrong, M.J. Mobile health use in low- and high-income countries: An overview of the peer-reviewed literature. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013, 106, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poushter, J.; Bishop, C.; Chwe, H. Social Media Use Continues to Rise in Developing Countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Res. Cent. 2018, 22, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cugelman, B.; Thelwall, M.; Dawes, P. Online interventions for social marketing health behavior change campaigns: A meta-analysis of psychological architectures and adherence factors. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubart, J.R.; Stuckey, H.L.; Ganeshamoorthy, A.; Sciamanna, C.N. Chronic health conditions and internet behavioral interventions: A review of factors to enhance user engagement. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2011, 29, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, P.; Prochaska, J.O.; Rossi, J.S. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustria, M.L.A.; Noar, S.M.; Cortese, J.; Van Stee, S.K.; Glueckauf, R.L.; Lee, J. A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 1039–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Sweet, C.M.; Chiguluri, V.; Gumpina, R.; Abbott, P.; Madero, E.N.; Payne, M.; Happe, L.; Matanich, R.; Renda, A.; Prewitt, T. Outcomes of a Digital Health Program with Human Coaching for Diabetes Risk Reduction in a Medicare Population. J. Aging Health 2018, 30, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zissimopoulos, J.; Crimmins, E.; St Clair, P. The Value of Delaying Alzheimer’s Disease Onset. Forum Health Econ. Policy 2014, 18, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Fratiglioni, L.; Matthews, F.E.; Lobo, A.; Breteler, M.M.B.; Skoog, I.; Brayne, C. Dementia in western Europe: Epidemiological evidence and implications for policy making. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; Wimo, A. Cost-effectiveness of a health intervention program with risk reductions for getting demented: Results of a Markov model in a Swedish/Finnish setting. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 26, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Title | Study Sample | Intervention Components | Study Length & Intervention Frequency | Primary Outcomes | Other Outcomes | Adherence/Attrition | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FINGER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MAPT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| preDIVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SPRINT-MIND |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Study Title | Sample/Sampling Method | Interventions | Study Length & Intervention Frequency | Main Outcomes | Issues Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age well.de |

|

|

|

|

|

| SMARRT |

|

|

|

|

|

| EMuNI |

|

|

|

|

|

| MIND-ADmini |

|

|

|

|

|

| Taiwan Multidomain Intervention Efficacy Study |

|

|

|

|

|

| Brain, Body, Life: General Practice, Lifestyle Modification Program (BBL-GPLMP) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Authors/Date | Sample/Sampling Method | Interventions | Study Length & Intervention Frequency | Main Outcomes | Differentiating Factors from FINGER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POINTER |

|

|

|

|

|

| SINGER |

|

|

|

|

|

| MIND-CHINA |

|

|

|

|

| Title | Sample/Sampling Method | Interventions | Availability | Study Length | Primary Outcomes | Issues Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DC-MARVEL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BBL-CD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HATICE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bott, N.T.; Hall, A.; Madero, E.N.; Glenn, J.M.; Fuseya, N.; Gills, J.L.; Gray, M. Face-to-Face and Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions to Enhance Cognitive Reserve and Reduce Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: A Review of Completed and Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092258

Bott NT, Hall A, Madero EN, Glenn JM, Fuseya N, Gills JL, Gray M. Face-to-Face and Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions to Enhance Cognitive Reserve and Reduce Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: A Review of Completed and Prospective Studies. Nutrients. 2019; 11(9):2258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092258

Chicago/Turabian StyleBott, Nicholas T., Aidan Hall, Erica N. Madero, Jordan M. Glenn, Nami Fuseya, Joshua L. Gills, and Michelle Gray. 2019. "Face-to-Face and Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions to Enhance Cognitive Reserve and Reduce Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: A Review of Completed and Prospective Studies" Nutrients 11, no. 9: 2258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092258

APA StyleBott, N. T., Hall, A., Madero, E. N., Glenn, J. M., Fuseya, N., Gills, J. L., & Gray, M. (2019). Face-to-Face and Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions to Enhance Cognitive Reserve and Reduce Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: A Review of Completed and Prospective Studies. Nutrients, 11(9), 2258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092258