Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

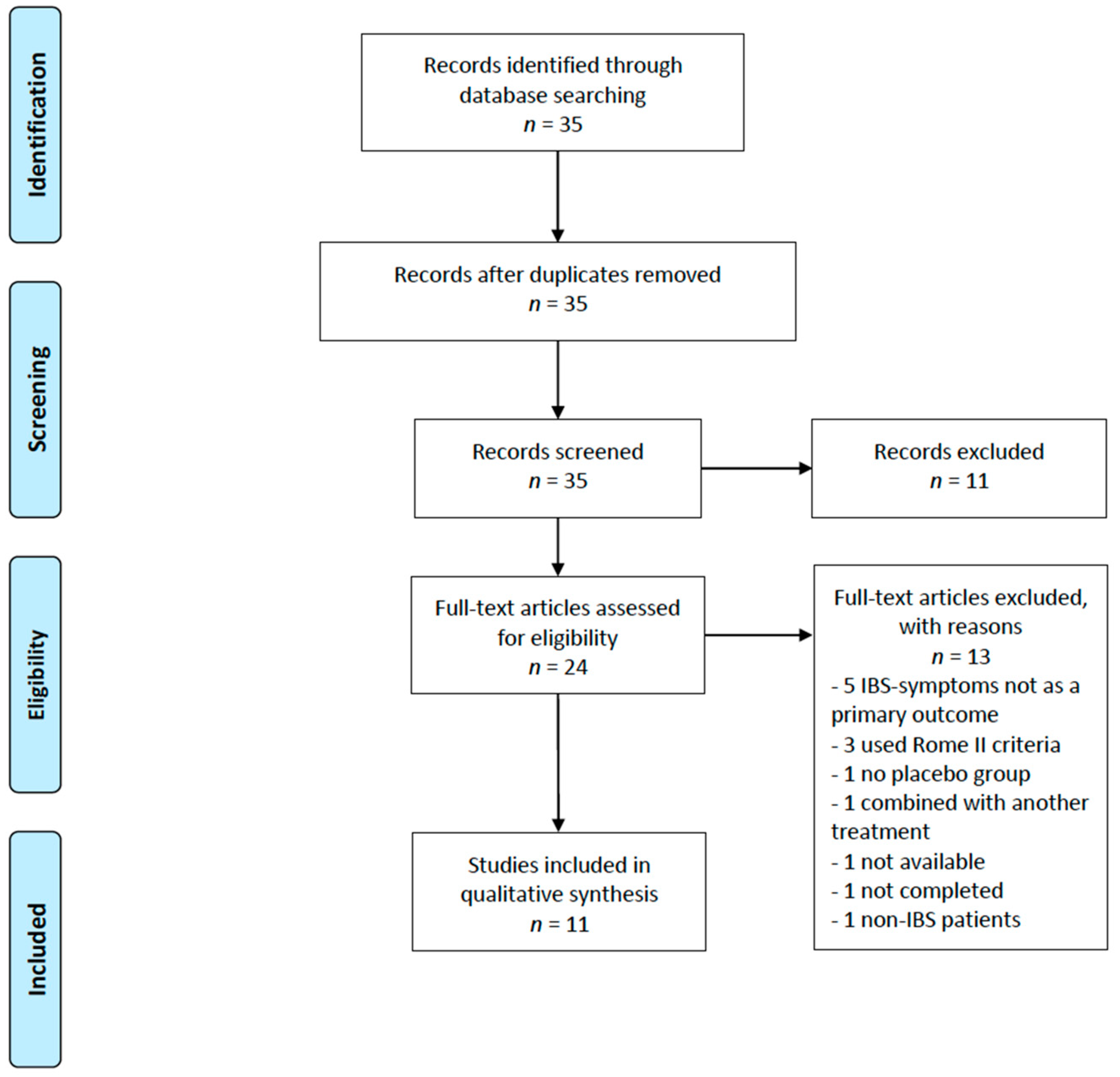

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Criteria for Inclusion

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Main Findings

3.3. Studies Evaluating the Effect of Mono-Strain Probiotics

3.4. Studies Evaluating the Effect of Multi-Strain Probiotics

3.5. Beneficial Probiotic Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lovell, R.M.; Ford, A.C. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, B.E.; Mearin, F.; Chang, L.; Chey, W.D.; Lembo, A.J.; Simren, M.; Spiller, R. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, G.; Feinle-Bisset, C.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Quigley, E.M.; Santos, J.; Vanner, S.; Vergnolle, N.; Zoetendal, E.G. The intestinal microenvironment and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longstreth, G.F.; Thompson, W.G.; Chey, W.D.; Houghton, L.A.; Mearin, F.; Spiller, R.C. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1480–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, A.; Eslick, E.M.; Eslick, G.D. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, R.; Whorwell, P.J. New insights into the psychosocial aspects of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2003, 5, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtmann, G.J.; Ford, A.C.; Talley, N.J. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.K.; Thabane, M.; Garg, A.X.; Clark, W.F.; Salvadori, M.; Collins, S.M. Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klem, F.; Wadhwa, A.; Prokop, L.J.; Sundt, W.J.; Farrugia, G.; Camilleri, M.; Singh, S.; Grover, M. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after infectious enteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. Jama 2004, 292, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, C.; Umesaki, Y.; Imaoka, A.; Handa, T.; Kanazawa, M.; Fukudo, S. Altered profiles of intestinal microbiota and organic acids may be the origin of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerckhoffs, A.P.; Samsom, M.; van der Rest, M.E.; de Vogel, J.; Knol, J.; Ben-Amor, K.; Akkermans, L.M. Lower Bifidobacteria counts in both duodenal mucosa-associated and fecal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 2887–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassinen, A.; Krogius-Kurikka, L.; Makivuokko, H.; Rinttila, T.; Paulin, L.; Corander, J.; Malinen, E.; Apajalahti, J.; Palva, A. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durban, A.; Abellan, J.J.; Jimenez-Hernandez, N.; Artacho, A.; Garrigues, V.; Ortiz, V.; Ponce, J.; Latorre, A.; Moya, A. Instability of the faecal microbiota in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 86, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tap, J.; Derrien, M.; Tornblom, H.; Brazeilles, R.; Cools-Portier, S.; Dore, J.; Storsrud, S.; Le Neve, B.; Ohman, L.; Simren, M. Identification of an intestinal microbiota signature associated with severity of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinen, E.; Krogius-Kurikka, L.; Lyra, A.; Nikkila, J.; Jaaskelainen, A.; Rinttila, T.; Vilpponen-Salmela, T.; von Wright, A.J.; Palva, A. Association of symptoms with gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4532–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.C.; Valiere, A. Probiotics and medical nutrition therapy. Nutr. Clin. Care 2004, 7, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, T.; Sequoia, J. Probiotics for gastrointestinal conditions: A summary of the evidence. Am. Fam. Phys. 2017, 96, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, M.L.; Romanuk, T.N. A meta-analysis of probiotic efficacy for gastrointestinal diseases. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremon, C.; Barbaro, M.R.; Ventura, M.; Barbara, G. Pre-and probiotic overview. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018, 43, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseaux, C.; Thuru, X.; Gelot, A.; Barnich, N.; Neut, C.; Dubuquoy, L.; Dubuquoy, C.; Merour, E.; Geboes, K.; Chamaillard, M.; et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdu, E.F.; Bercik, P.; Verma-Gandhu, M.; Huang, X.X.; Blennerhassett, P.; Jackson, W.; Mao, Y.; Wang, L.; Rochat, F.; Collins, S.M. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut 2006, 55, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, K.; Cornish, A.; Soper, P.; McKaigney, C.; Jijon, H.; Yachimec, C.; Doyle, J.; Jewell, L.; De Simone, C. Probiotic bacteria enhance murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology 2001, 121, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, L.; McCarthy, J.; Kelly, P.; Hurley, G.; Luo, F.; Chen, K.; O’Sullivan, G.C.; Kiely, B.; Collins, J.K.; Shanahan, F.; et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: Symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, G.; Cremon, C.; Azpiroz, F. Probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Where are we? Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30, e13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyra, A.; Hillila, M.; Huttunen, T.; Mannikko, S.; Taalikka, M.; Tennila, J.; Tarpila, A.; Lahtinen, S.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Veijola, L. Irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity improves equally with probiotic and placebo. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10631–10642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Natarajan, S.; Sivakumar, A.; Ali, F.; Pande, A.; Majeed, S.; Karri, S.K. Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 supplementation in the management of diarrhea predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A double blind randomized placebo controlled pilot clinical study. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineton de Chambrun, G.; Neut, C.; Chau, A.; Cazaubiel, M.; Pelerin, F.; Justen, P.; Desreumaux, P. A randomized clinical trial of Saccharomyces cerevisiae versus placebo in the irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hod, K.; Sperber, A.D.; Ron, Y.; Boaz, M.; Dickman, R.; Berliner, S.; Halpern, Z.; Maharshak, N.; Dekel, R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the effect of a probiotic mixture on symptoms and inflammatory markers in women with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishaque, S.M.; Khosruzzaman, S.M.; Ahmed, D.S.; Sah, M.P. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of a multi-strain probiotic formulation (Bio-Kult(R)) in the management of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, E.; Vahedi, H.; Merat, S.; Momtahen, S.; Riahi, A. Therapeutic effects, tolerability and safety of a multi-strain probiotic in Iranian adults with irritable bowel syndrome and bloating. Arch. Iran. Med. 2014, 17, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ludidi, S.; Jonkers, D.M.; Koning, C.J.; Kruimel, J.W.; Mulder, L.; van der Vaart, I.B.; Conchillo, J.M.; Masclee, A.A. Randomized clinical trial on the effect of a multispecies probiotic on visceroperception in hypersensitive IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzasalma, V.; Manfrini, E.; Ferri, E.; Sandionigi, A.; La Ferla, B.; Schiano, I.; Michelotti, A.; Nobile, V.; Labra, M.; Di Gennaro, P. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: The efficacy of multispecies probiotic supplementation in alleviating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome associated with constipation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 4740907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisson, G.; Ayis, S.; Sherwood, R.A.; Bjarnason, I. Randomised clinical trial: A liquid multi-strain probiotic vs. placebo in the irritable bowel syndrome–A 12 week double-blind study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Farquharson, F.M.; Louis, P.; Fava, F.; Franciosi, E.; Scholz, M.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Irving, P.M.; et al. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and a probiotic restores bifidobacterium species: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.K.; Yang, C.; Song, G.H.; Wong, J.; Ho, K.Y. Melatonin regulation as a possible mechanism for probiotic (VSL#3) in irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized double-blinded placebo study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, A.C.; Harris, L.A.; Lacy, B.E.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Moayyedi, P. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.C.; Quigley, E.M.; Lacy, B.E.; Lembo, A.J.; Saito, Y.A.; Schiller, L.R.; Soffer, E.E.; Spiegel, B.M.; Moayyedi, P. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungin, A.P.S.; Mitchell, C.R.; Whorwell, P.; Mulligan, C.; Cole, O.; Agreus, L.; Fracasso, P.; Lionis, C.; Mendive, J.; Philippart de Foy, J.M.; et al. Systematic review: Probiotics in the management of lower gastrointestinal symptoms—An updated evidence-based international consensus. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsari, A.; Ceccarelli, A.; Dubini, F.; Fesce, E.; Poli, G. The fecal microbial population in the irritable bowel syndrome. Microbiologica 1982, 5, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rajilic-Stojanovic, M.; Biagi, E.; Heilig, H.G.; Kajander, K.; Kekkonen, R.A.; Tims, S.; de Vos, W.M. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, C.Y.; Morris, J.; Whorwell, P.J. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: A simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswaran, S.L.; Chey, W.D.; Han-Markey, T.; Ball, S.; Jackson, K. A randomized controlled trial comparing the low FODMAP diet vs. modified NICE guidelines in US adults with IBS-D. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, A.C.; Moayyedi, P.; Lacy, B.E.; Lembo, A.J.; Saito, Y.A.; Schiller, L.R.; Soffer, E.E.; Spiegel, B.M.; Quigley, E.M. American college of gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.; Mayer, E.A.; Drossman, D.A.; Heath, A.; Dukes, G.E.; McSorley, D.; Kong, S.; Mangel, A.W.; Northcutt, A.R. Improvement in pain and bowel function in female irritable bowel patients with alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 13, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, P.W.; Marchesi, J.R.; Hill, C. Next-generation probiotics: The spectrum from probiotics to live biotherapeutics. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| IBS patients | Healthy adults or non-IBS patients |

| Human studies | Animal studies |

| Studies in adults (over 18 years) | Studies in children |

| RCT studies | Studies without RCT methodology |

| Double- or triple-blinded studies | Single-blinded or partially blinded studies |

| Studies published the last five years | Studies older than five years |

| IBS diagnosis with Rome III or Rome IV criteria | IBS diagnosis with Rome II or Manning criteria |

| Studies looking at change in IBS symptoms as primary outcome | Studies not looking at change in IBS symptoms as primary outcome |

| Studies looking solemnly at probiotics in an intervention group | Studies looking at probiotics in conjunction with other IBS therapy in the same intervention group |

| First Author, Year of Publication, Country | N | Probiotic Strains (Amount) | Dose | Probiotic Form | IBS Subtype | Gender | Study Duration | Symptom Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-strain probiotics | ||||||||

| Lyra, 2016, Finland [28] | 391 | Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM (low dose: 109 CFU, high dose: 1010 CFU) | Once daily | Capsule | Not specified | Both | 12 weeks | IBS-SSS, QoL, and HADS |

| Majeed, 2016, India [29] | 36 | Bacillus coagulans MTCC5856 (2 × 109 CFU) | Once daily | Tablet | IBS-D | Both | 90 days | VAS, Physician’s evaluation, and QoL |

| Pineton, 2015, France [30] | 179 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856 (500 mg, 8 × 109 CFU/g) | Once daily | Capsule | Not specified | Both | 8 weeks | 7-point Likert scale and CMH |

| Multi-strain probiotics | ||||||||

| Hod, 2017, Israel [31] | 107 | Lactobacillus rhamnosus LR5 (3 × 109 CFU), L. casei LC5 (2 × 109 CFU), L. paracasei LPC5 (1 × 109 CFU), L. plantarum LP3 (1 × 109 CFU), L. acidophilus LA1 (5 × 109 CFU), Bifidobacterium bifidum BF3 (4 × 109 CFU), B. longum BG7 (1 × 109 CFU), B. breve BR3 (2 × 109 CFU), B. infantis BT1 (1 × 109 CFU), Streptococcus thermophilus ST3 (2 × 109 CFU), L. bulgaricus LG1, and Lactococcus lactis SL6 (3 × 109 CFU) | Twice daily | Capsule | IBS-D | Female | 8 weeks | VAS |

| Ishaque, 2018, Bangladesh [32] | 400 | Bacillus subtilis PXN 21, Bifidobacterium bifidum PXN 23, B. breve PXN 25, B. infantis PXN 27, B. longum PXN 30, Lactobacillus acidophilus PXN 35, L. delbrueckii. Bulgaricus PXN39, L. casei PXN 37, L. plantarum PXN 47, L. rhamnosus PXN 54, L. helveticus PXN 45, L. salivarius PXN 57, Lactococcus lactis PXN 63, and Streptococcus thermophilus PXN 66 (in total 8 × 109 CFU) | 2 × twice daily | Capsule | IBS-D | Both | 16 weeks | IBS-SSS |

| Jafari, 2014, Iran [33] | 108 | Bifidobacterium animalis lactis BB-12, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. delbrueckii bulgaricus LBY-27, and Streptococcus thermophilus STY-31 (in total approx. 4 × 109 CFU) | Twice daily | Capsule | Not specified | Both | 4 weeks | VAS |

| Ludidi, 2014, The Netherlands [34] | 40 | Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus casei W56, L. salivarius W 57, L. acidophilus NCFM, L. rhamnosus W71, and Lactococcus lactis W58 (in total 5 × 109 CFU) | Once daily | Powder mixed in water | Not specified | Both | 6 weeks | 5-point Likert scale, barostat, and VAS |

| Mezzasalma, 2016, Italy [35] | 157 | F1: Lactobacillus acidophilus (5 × 109 CFU) and L. reuteri (5 × 109 CFU); F2: Lactobacillus plantarum (5 × 109 CFU), L. rhamnosus (5 × 109 CFU), and Bifidobacterium animalis lactis (5 × 109 CFU) | Once daily | Capsule | IBS-C | Both | 60 days | VAS and QoL |

| Sisson, 2014, United Kingdom [36] | 186 | Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, and Enterococcus faecium (in total approx. 1010 CFU) | Once daily | Liquid | Not specified | Both | 12 weeks | IBS-SSS |

| Staudacher, 2017, United Kingdom [37] | 53 | Streptococcus thermophilus DSM 24731, Bifidobacterium breve DSM 24732, B. longum DSM 24736, B. infantis DSM 24737, Lactobacillus acidophilus DSM 24735, L. plantarum DSM 24730, L. paracasei DSM 24733, and L. delbrueckii. bulgaricus DSM 24734 (in total 11,95 log10 CFU) | Once daily | Powder mixed in water | IBS-D, -M, and -U | Both | 4 weeks | IBS-SSS |

| Wong, 2015, Singapore [38] | 42 | Bifidobacterium longum, B. infantis, B. breve, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, L. delbrueckii bulgaricus, L. plantarum, and Streptococcus salivarius thermophilus (in total 112.5 billion) | 4 × 2 daily | Capsule | Not specified | Both | 6 weeks | IBS-SSS, HADS, SBDQ, and barostat |

| First Author, Year Published, Country | Primary Outcome | Main Findings, Primary Outcome | Secondary Outcome | Main Findings, Secondary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-strain probiotics | ||||

| Lyra, 2016, Finland [28] | Change in IBS-SSS scores | Sign. improvement in all three groups, but no sign. difference between groups | Change in anxiety and depression scores and adequate relief | No sign. differences between groups |

| Majeed, 2016, India [29] | Bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, stool frequency and consistency | Sign. improvement in all mentioned symptoms in IG compared to PG | Physician’s global assessment of disease severity and QoL | Sign. difference in improvement of disease severity and QoL |

| Pineton, 2014, France [30] | Change in abdominal pain/discomfort | Sign. improvement in both group from baseline, but no sign. difference between IG and PG | Change in bloating/distention and bowel movement difficulty | Sign. improvement in both group from baseline, but no sign. difference between them |

| Multi-strain probiotics | ||||

| Hod, 2017, Israel [31] | Degree of symptom relief | Sign. improvement in both groups. Only sign. result was an improvement in abdominal pain in the PG compared to IG | Bloating, urgency, and frequency of bowel movements and inflammatory markers (FC and Hs-CRP) | No sign. results |

| Ishaque, 2018, Bangladesh [32] | The change in severity and frequency of abdominal pain on the IBS-SSS | Abdominal pain level decreased by 40 points in the IG versus a 27 point decrease in the PG | The change in other GI symptom severity scores on the IBS-SSS, QoL, and AEs | Sign. improvement in IG in IBS symptoms and QoL |

| Jafari, 2014, Iran [33] | Reduction in mean abdominal bloating score and “satisfactory relief” | The IG had an improvement in abdominal bloating. Satisfactory relief was 85% reduced in IG compared to 47% in PG | Changes in abdominal pain or discomfort score and reduction in feeling of incomplete defecation | Feeling of incomplete defecation was reduced in IG abdominal pain scores were lower in IG compared to PG after one month follow-up |

| Ludidi, 2014, The Netherlands [34] | Visceral perception | Sign. improvement in both groups, but no difference between them | Symptom scores (number of symptom-free days and MMS) | PG showed a decrease in MMS, but the difference between the groups was not significant. No sign. difference in number of symptom-free days |

| Mezzasalma, 2016, Italy [35] | Number of symptom-free days and fecal microbiota | Sign. improvement in the two IGs compared to PG in number of symptom-free days and increased amount of the supplemented species in the two IGs feces samples | Maintenance of effect after 30 d of wash-out and QoL | Maintenance of intervention effect was sign. higher in the two IGs than in the PG improvement in QoL in IGs compared to PG |

| Sisson, 2013, United Kingdom [36] | Change in overall IBS-SSS scores | Sign. improvement in overall symptoms in IG compared to PG | QoL and change in IBS-SSS components after 12 w intervention and 4 w follow-up | Improvement in bowel movements was sign. better in the IG. No difference in QoL scores. No sign. results after 4 w |

| Staudacher, 2017, United Kingdom [37] | “Adequate symptom relief” and fecal Bifidobacterium species concentration | Adequate symptom relief was reported in 57% in IG compared to 37% in PG. A greater abundance of the Bifidobacterium was found in the IG compared to PG | Individual GI symptoms (IBS-SSS and GSRS), stool output, HRQOL, microbiota diversity, and nutrient intake | Flatulence scores were sign. lower in IG compared to PG. No other sign. differences were found between the groups |

| Wong, 2015, Singapore [38] | Change in IBS-SSS scores | Change in pain duration and abdominal distention decreased sign. in IG compared to PG | Rectal sensitivity and saliva melatonin levels | No sign. results |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dale, H.F.; Rasmussen, S.H.; Asiller, Ö.Ö.; Lied, G.A. Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092048

Dale HF, Rasmussen SH, Asiller ÖÖ, Lied GA. Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019; 11(9):2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092048

Chicago/Turabian StyleDale, Hanna Fjeldheim, Stella Hellgren Rasmussen, Özgün Ömer Asiller, and Gülen Arslan Lied. 2019. "Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review" Nutrients 11, no. 9: 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092048

APA StyleDale, H. F., Rasmussen, S. H., Asiller, Ö. Ö., & Lied, G. A. (2019). Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients, 11(9), 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092048