Comparison of Major Protein-Source Foods and Other Food Groups in Meat-Eaters and Non-Meat-Eaters in the EPIC-Oxford Cohort

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Assessment of Diet and Diet Group

2.3. Eligibility

2.4. Statistical Analysis

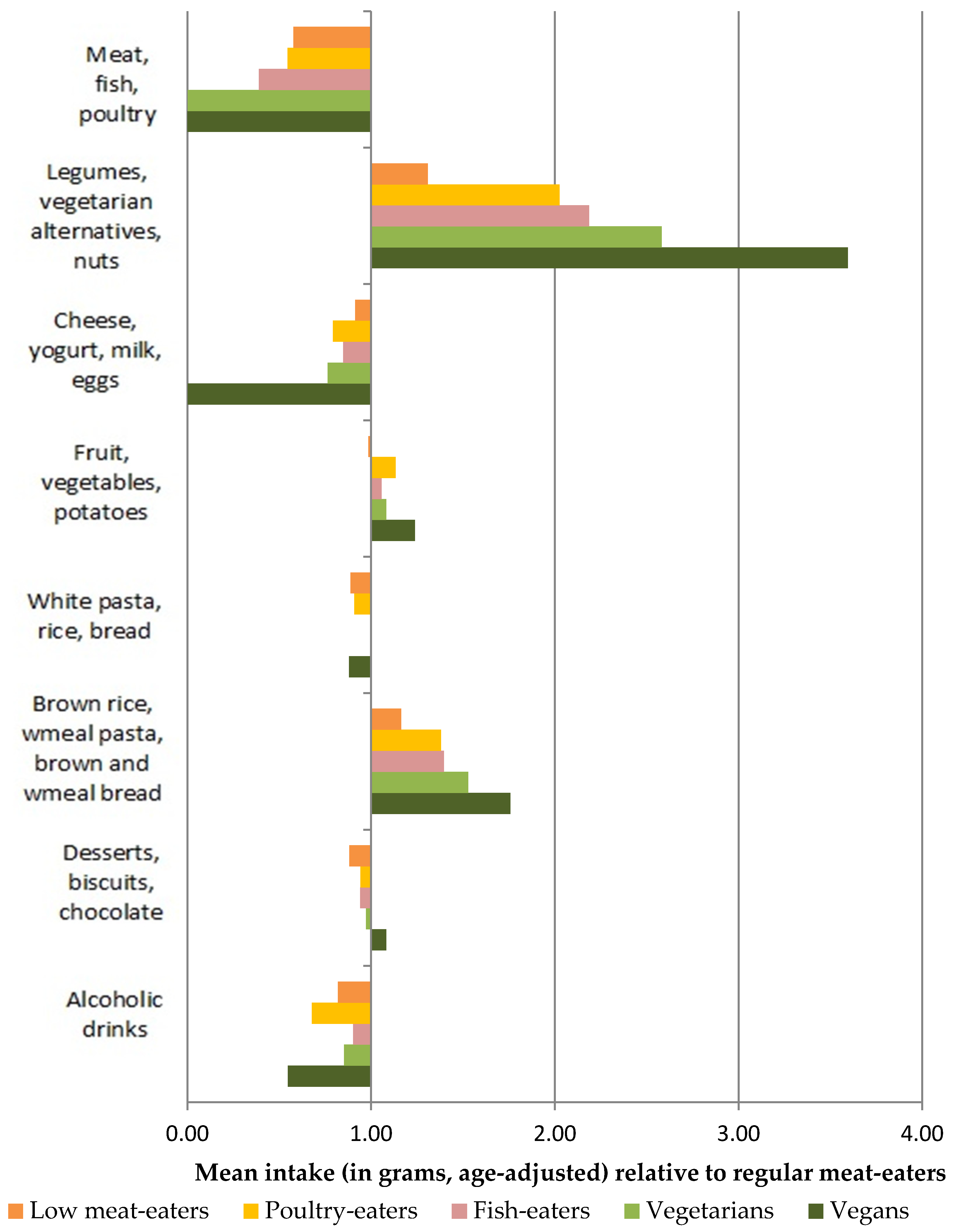

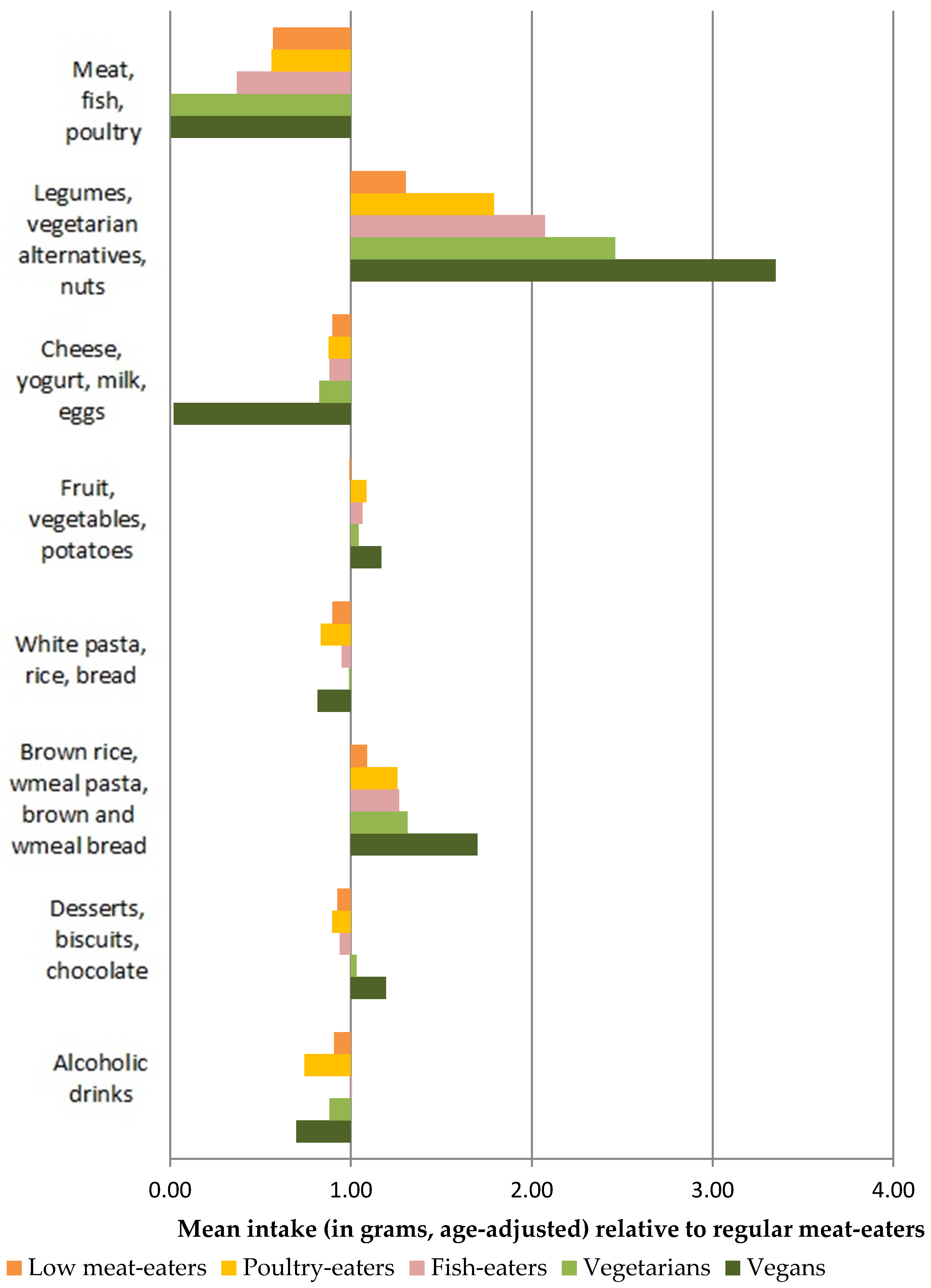

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leitzmann, C. Vegetarian nutrition: Past, present, future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, G.K.; Spencer, E.A.; Appleby, P.N.; Allen, N.E.; Knox, K.H.; Key, T.J. EPIC–Oxford:lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Heal. Nutr. 2003, 6, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, F.L.; Appleby, P.N.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Risk of hospitalization or death from ischemic heart disease among British vegetarians and nonvegetarians: Results from the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, F.L.; Appleby, P.N.; Allen, N.E.; Key, T.J. Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): Prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. BMJ 2011, 343, d4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, P.N.; Allen, N.E.; Key, T.J. Diet, vegetarianism, and cataract risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Crowe, F.L.; Bradbury, K.E.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C. Cancer in British vegetarians: Updated analyses of 4998 incident cancers in a cohort of 32,491 meat eaters, 8612 fish eaters, 18,298 vegetarians, and 2246 vegans1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 378S–385S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lousuebsakul-Matthews, V.; Thorpe, D.L.; Knutsen, R.; Beeson, W.L.; Fraser, G.E.; Knutsen, S.F. Legumes and meat analogues consumption are associated with hip fracture risk independently of meat intake among Caucasian men and women: The Adventist Health Study-2. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2333–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, D.L.; Knutsen, S.F.; Beeson, W.L.; Rajaram, S.; Fraser, G.E. Effects of meat consumption and vegetarian diet on risk of wrist fracture over 25 years in a cohort of peri- and postmenopausal women. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.H.; Lin, M.-N.; Pan, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-L. Vegetarian diet, food substitution, and nonalcoholic fatty liver. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2018, 30, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, A.M.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C. Major Dietary Protein Sources and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women. Circulation 2010, 122, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.M.; Pan, A.; Rexrode, K.M.; Stampfer, M.; Hu, F.B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Willett, W.C. Dietary protein sources and the risk of stroke in men and women. Stroke 2012, 43, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Bernstein, A.M.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Red meat consumption and mortality: Results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, J.L.; Barr, S.I. Diets and selected lifestyle practices of self-defined adult vegetarians from a population-based sample suggest they are more ’health conscious’. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2005, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, K.E.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Key, T.J. Dietary Intake of High-Protein Foods and Other Major Foods in Meat-Eaters, Poultry-Eaters, Fish-Eaters, Vegetarians, and Vegans in UK Biobank. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarys, P.; Deliens, T.; Huybrechts, I.; Deriemaeker, P.; Vanaelst, B.; De Keyzer, W.; Hebbelinck, M.; Mullie, P. Comparison of Nutritional Quality of the Vegan, Vegetarian, Semi-Vegetarian, Pesco-Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diet. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorinne, A.-L.; Alfthan, G.; Erlund, I.; Kivimäki, H.; Paju, A.; Salminen, I.; Turpeinen, U.; Voutilainen, S.; Laakso, J. Food and Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Finnish Vegans and Non-Vegetarians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsing, A.M.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Goldbohm, R.A.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Brandt, P.A.V.D.; Schouten, L.J. The Netherlands Cohort Study—Meat Investigation Cohort; a population-based cohort over-represented with vegetarians, pescetarians and low meat consumers. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.H.; Tanzman, J.S. What do vegetarians in the United States eat? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 626S–632S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlich, M.J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabaté, J.; Fan, J.; Singh, P.N.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of food consumption among vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, A.; Mena, P.; Pellegrini, N.; Turroni, S.; Neviani, E.; Ferrocino, I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ruini, L.; Ciati, R.; Angelino, D.; et al. Environmental impact of omnivorous, ovo-lacto-vegetarian, and vegan diet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, M.; Montonen, J.; Härkänen, T.; Männistö, S. Identifying vegetarians and their food consumption according to self-identification and operationalized definition in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, S.A.; Gill, C.; Welch, A.; Cassidy, A.; Runswick, S.A.; Oakes, S.; Lubin, R.; Thurnham, D.I.; Key, T.J.; Roe, L.; et al. Validation of dietary assessment methods in the UK arm of EPIC using weighed records, and 24-hour urinary nitrogen and potassium and serum vitamin C and carotenoids as biomarkers. Int. J. Epidemiology 1997, 26, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPIC-Oxford study design, ethics and regulation. Available online: http://www.epic-oxford.org/files/epic-followup3-140910.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food, Food Portion Sizes, 2nd ed.; Her Majesty’s Stationary Office: London, UK, 1993.

- Paul, A.A.; Southgate, D.A. McCance and Widdowson’s the Composition of Foods, 5th ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sobiecki, J.G.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Key, T.J. High compliance with dietary recommendations in a cohort of meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians, and vegans: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition–Oxford study☆☆☆. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H.W.; Vadiveloo, M.K. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Eatwell Guide. Helping You Eat a Healthy, Balanced Diet. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/742750/Eatwell_Guide_booklet_2018v4.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2019).

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Spencer, E.A.; Travis, R.C.; Roddam, A.W.; Allen, N.E. Mortality in British vegetarians: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, M.B.E.; Black, A.E. Markers of the Validity of Reported Energy Intake. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 895S–920S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Diet Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Meat-Eaters | Low Meat-Eaters | Poultry-Eaters | Fish-Eaters | Vegetarians | Vegans | |

| Men | n = 2852 | n = 880 | n = 65 | n = 782 | n = 1516 | n = 269 |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Age a | 63.5 ± 11.6 | 62.7 ± 11.9 | 59.2 ± 11.5 | 58.3 ± 11.2 | 56.1 ± 11.0 | 54.2 ± 11.1 |

| Higher education b | 1230 (46.2) | 420 (51.0) | 33 (52.4) | 477 (63.1) | 817 (56.0) | 124 (47.0) |

| High SES b, c | 803 (31.4) | 213 (27.4) | 10 (16.1) | 142 (20.5) | 305 (22.7) | 54 (22.4) |

| Lifestyle and health | ||||||

| Current smokers b | 385 (13.5) | 120 (13.7) | 4 (6.2) | 95 (12.2) | 149 (9.9) | 19 (7.1) |

| Alcohol (grams) | 17.6 ± 18.5 | 14.8 ± 16.4 | 11.6 ± 16.0 | 15.5 ± 17.3 | 14.9 ± 18.6 | 11.3 ± 16.6 |

| High physical activity level b | 380 (14.4) | 151 (18.8) | 19 (32.8) | 142 (19.9) | 297 (21.0) | 67 (26.2) |

| Body mass index b | 24.9 ± 3.2 | 23.9 ± 3.0 | 23.3 ± 3.1 | 23.5 ± 3.3 | 23.3 ± 2.9 | 22.8 ± 3.3 |

| Diet | ||||||

| Total energy kcal | 2314 ± 551.8 | 2088 ± 557.4 | 2255 ± 616.0 | 2211 ± 578.5 | 2192 ± 566.1 | 2132 ± 633.4 |

| Carbohydrate (%E) | 49.7 ± 6.2 | 52.4 ± 6.2 | 53.8 ± 7.2 | 53.0 ± 6.3 | 54.7 ± 6.4 | 56.6 ± 8.2 |

| Protein (%E) | 16.6 ± 2.4 | 15.2 ± 2.0 | 15.1 ± 2.3 | 14.8 ± 2.2 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | 12.5 ± 1.8 |

| Total fat (%E) | 31.6 ± 4.6 | 30.7 ± 4.7 | 30.9 ± 6.7 | 30.6 ± 4.9 | 30.5 ± 5.3 | 31.0 ± 7.4 |

| Women | n = 10,145 | n = 3770 | n = 526 | n = 3746 | n = 5156 | n = 532 |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Age a | 60.4 ± 11.7 | 59.3 ± 12.0 | 57.6 ± 12.2 | 55.7 ± 11.4 | 52.9 ± 11.2 | 52.0 ± 11.1 |

| Higher education b | 2942 (31.1) | 1396 (39.3) | 195 (38.8) | 1613 (45.0) | 2126 (42.8) | 208 (40.9) |

| High SES b, c | 2554 (28.8) | 805 (24.2) | 104 (22.2) | 785 (23.7) | 1125 (24.4) | 81 (16.9) |

| Lifestyle and health | ||||||

| Current smokers b | 985 (9.8) | 337 (9.0) | 33 (6.3) | 312 (8.4) | 409 (8.0) | 45 (8.5) |

| Alcohol (grams) | 8.3 ± 9.6 | 7.9 ± 9.7 | 6.7 ± 8.0 | 8.6 ± 10.3 | 7.7 ± 9.9 | 6.6 ± 10.4 |

| High physical activity level b | 896 (10.6) | 442 (13.5) | 73 (16.0) | 501 (15.1) | 620 (13.3) | 77 (16.0) |

| Body mass index b | 24.3 ± 4.1 | 23.4 ± 3.7 | 22.7 ± 3.9 | 22.6 ± 3.1 | 22.7 ± 3.5 | 22.1 ± 2.9 |

| Diet | ||||||

| Total energy kcal | 2110 ± 481.2 | 1900 ± 489.1 | 1932 ± 501.1 | 1974 ± 489.5 | 1940 ± 491.4 | 1880 ± 519.5 |

| Carbohydrate (%E) | 49.3 ± 6.2 | 52.4 ± 6.5 | 52.4 ± 7.2 | 52.9 ± 6.3 | 55.4 ± 6.5 | 56.4 ± 7.1 |

| Protein (%E) | 17.6 ± 2.5 | 15.9 ± 2.2 | 16.6 ± 2.7 | 15.4 ± 2.2 | 13.8 ± 1.9 | 13.0 ± 1.7 |

| Total fat (%E) | 32.4 ± 4.9 | 31.1 ± 5.4 | 31.0 ± 6.2 | 30.9 ± 5.5 | 30.5 ± 5.7 | 31.0 ± 6.3 |

| Protein source | Diet Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Meat-Eaters | Low Meat-Eaters | Poultry-Eaters | Fish-Eaters | Vegetarians | Vegans | |

| n = 2852 | n = 880 | n = 65 | n = 782 | n = 1516 | n = 269 | |

| Red meat | ||||||

| g/day | 42.9 | 18.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 38.3 | 19.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Processed meat | ||||||

| g/day | 15.5 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 13.9 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Poultry | ||||||

| g/day | 36.5 | 10.5 | 23.4 | - | - | - |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 32.9 | 10.9 | 22.4 | - | - | - |

| Oily fish | ||||||

| g/day | 14.3 | 14.1 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 12.6 | 14.0 | 17.4 | 17.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Non-oily fish | ||||||

| g/day | 39.1 | 35.2 | 38.2 | 39.4 | - | - |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 35.1 | 35.4 | 34.5 | 37.4 | - | - |

| Legumes/pulses | ||||||

| g/day | 30.1 | 33.2 | 37.3 | 42.4 | 48.4 | 68.6 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 26.7 | 32.5 | 33.6 | 39.3 | 45.7 | 68.4 |

| Vegetarian protein alternatives | ||||||

| g/day | 5.5 | 13.6 | 31.3 | 41.2 | 50.6 | 61.0 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 4.9 | 12.9 | 27.2 | 38.0 | 47.7 | 59.6 |

| Nuts | ||||||

| g/day | 10.7 | 13.8 | 25.1 | 17.5 | 20.5 | 36.6 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 8.9 | 12.4 | 21.9 | 15.4 | 17.9 | 32.6 |

| Cheese | ||||||

| g/day | 21.3 | 22.3 | 20.6 | 29.6 | 33.2 | - |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 18.5 | 21.0 | 18.8 | 26.6 | 30.1 | - |

| Yogurt | ||||||

| g/day | 43.9 | 42.9 | 48.9 | 50.8 | 40.7 | 1.2 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 38.1 | 41.0 | 44.4 | 46.0 | 36.9 | 0.8 |

| Dairy milk | ||||||

| g/day | 280.6 | 250.4 | 203.1 | 208.9 | 186.6 | 0.0 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 245.3 | 243.2 | 183.8 | 192.1 | 171.4 | - |

| Plant milk | ||||||

| g/day | 6.1 | 14.1 | 36.3 | 31.8 | 55.4 | 210.3 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 5.7 | 14.6 | 38.1 | 30.6 | 53.8 | 200.1 |

| Eggs | ||||||

| g/day | 19.7 | 18.3 | 16.8 | 20.6 | 18.6 | 0.0 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 17.7 | 18.1 | 15.4 | 19.5 | 17.7 | 0.0 |

| Protein Source | Diet Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Meat-Eaters | Low Meat-Eaters | Poultry-Eaters | Fish-Eaters | Vegetarians | Vegans | |

| n = 10,145 | n = 3770 | n = 526 | n = 3746 | n = 5156 | n = 532 | |

| Red meat | ||||||

| g/day | 40.4 | 17.5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 39.6 | 19.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Processed meat | ||||||

| g/day | 12.4 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 12.1 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Poultry | ||||||

| g/day | 40.3 | 11.5 | 28.1 | 0.1 | - | - |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 39.8 | 13.0 | 30.9 | 0.1 | - | - |

| Oily fish | ||||||

| g/day | 15.5 | 14.6 | 19.0 | 17.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 15.0 | 15.8 | 20.6 | 18.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Non-oily fish | ||||||

| g/day | 39.1 | 34.2 | 35.9 | 36.7 | - | - |

| g/2000 kcal/day | 38.2 | 37.4 | 38.4 | 38.7 | - | - |

| Legumes/pulses | ||||||

| g/day | 28.5 | 30.9 | 36.8 | 39.6 | 44.7 | 63.0 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 27.6 | 33.1 | 38.3 | 41.1 | 47.5 | 68.9 |

| Vegetarian protein alternatives | ||||||

| g/day | 5.5 | 13.5 | 25.8 | 36.3 | 47.8 | 60.0 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 5.3 | 14.0 | 26.9 | 37.2 | 50.0 | 64.9 |

| Nuts | ||||||

| g/day | 11.3 | 14.7 | 18.6 | 18.1 | 19.0 | 28.8 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 10.3 | 14.6 | 17.9 | 17.7 | 18.7 | 29.7 |

| Cheese | ||||||

| g/day | 20.3 | 19.6 | 20.3 | 25.7 | 28.4 | 0.3 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 19.2 | 20.5 | 20.6 | 26.0 | 29.2 | 0.3 |

| Yogurt | ||||||

| g/day | 58.8 | 55.6 | 59.5 | 60.5 | 55.0 | 1.7 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 56.1 | 58.5 | 62.3 | 61.4 | 56.9 | 1.5 |

| Dairy milk | ||||||

| g/day | 250.9 | 221.4 | 208.6 | 202.4 | 187.2 | 4.9 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 240.7 | 237.9 | 217.8 | 206.4 | 194.9 | 4.4 |

| Plant milk | ||||||

| g/day | 11.9 | 17.6 | 32.7 | 36.1 | 47.7 | 217.9 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 12.1 | 19.1 | 35.2 | 38.5 | 50.5 | 233.5 |

| Eggs | ||||||

| g/day | 18.7 | 16.6 | 17.5 | 18.8 | 17.0 | 0.2 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 18.3 | 18.0 | 18.6 | 19.5 | 18.0 | 0.2 |

| Food Group | Diet Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Meat-Eaters | Low Meat-Eaters | Poultry-Eaters | Fish-Eaters | Vegetarians | Vegans | p for Difference b | |

| n = 2852 | n = 880 | n = 65 | n = 782 | n = 1516 | n = 269 | ||

| Fruit | |||||||

| g/day | 217 | 231 | 299 | 230 | 233 | 277 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 190 | 224 | 262 | 214 | 217 | 281 | <0.0001 |

| Vegetables | |||||||

| g/day | 255 | 258 | 280 | 297 | 305 | 347 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 227 | 255 | 264 | 277 | 287 | 343 | <0.0001 |

| Potatoes—boiled, mashed or jacket | |||||||

| g/day | 93 | 76 | 76 | 81 | 81 | 87 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 82 | 74 | 66 | 73 | 75 | 82 | <0.0001 |

| Potatoes—fried, roasted | |||||||

| g/day | 31 | 23 | 21 | 23 | 27 | 28 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 27 | 23 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| White pasta/noodles | |||||||

| g/day | 36 | 33 | 40 | 38 | 37 | 23 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 32 | 32 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 22 | <0.0001 |

| Wholemeal pasta | |||||||

| g/day | 14 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 25 | 28 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 12 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 29 | <0.0001 |

| Couscous, bulgur wheat | |||||||

| g/day | 7 | 9 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 6 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| White rice | |||||||

| g/day | 24 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 18 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 22 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 0.0706 |

| Brown rice | |||||||

| g/day | 11 | 14 | 24 | 19 | 19 | 27 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 10 | 14 | 24 | 18 | 18 | 27 | <0.0001 |

| Pizza | |||||||

| g/day | 10 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 5 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 9 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 5 | <0.0001 |

| White bread | |||||||

| g/day | 27 | 21 | 12 | 22 | 22 | 24 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 23 | 20 | 9 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 0.0002 |

| Brown bread | |||||||

| g/day | 20 | 20 | 14 | 19 | 21 | 16 | 0.2225 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 17 | 18 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 15 | 0.1262 |

| Wholemeal bread | |||||||

| g/day | 36 | 43 | 54 | 50 | 59 | 71 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 31 | 38 | 45 | 44 | 51 | 63 | <0.0001 |

| Other bread | |||||||

| g/day | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| Porridge | |||||||

| g/day | 33 | 40 | 43 | 40 | 33 | 44 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 30 | 39 | 45 | 39 | 32 | 44 | <0.0001 |

| Breakfast cereal | |||||||

| g/day | 33 | 31 | 37 | 32 | 34 | 33 | 0.1723 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 29 | 30 | 34 | 28 | 31 | 30 | 0.0754 |

| Cereal bars | |||||||

| g/day | 12 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 0.3626 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 10 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 0.0680 |

| Chocolate | |||||||

| g/day | 13 | 12 | 18 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 0.0519 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 11 | 11 | 15 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 0.0561 |

| Cake | |||||||

| g/day | 34 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 32 | 25 | 0.0021 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 29 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 28 | 22 | 0.0054 |

| Ice cream | |||||||

| g/day | 15 | 12 | 17 | 12 | 13 | 10 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 13 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 9 | <0.0001 |

| Milk desserts | |||||||

| g/day | 53 | 43 | 31 | 45 | 46 | 44 | 0.0012 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 44 | 41 | 26 | 39 | 41 | 35 | 0.0152 |

| Soya dessert | |||||||

| g/day | 1 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 38 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 1 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 39 | <0.0001 |

| Crisps | |||||||

| g/day | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Tea | |||||||

| g/day | 483 | 461 | 472 | 495 | 468 | 419 | 0.0146 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 435 | 458 | 437 | 470 | 445 | 420 | 0.0983 |

| Coffee | |||||||

| g/day | 342 | 292 | 183 | 268 | 290 | 204 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 306 | 294 | 164 | 257 | 277 | 195 | <0.0001 |

| Fruit smoothie | |||||||

| g/day | 133 | 124 | 169 | 153 | 142 | 148 | 0.0029 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 115 | 122 | 144 | 138 | 129 | 141 | 0.0003 |

| Fruit squash | |||||||

| g/day | 70 | 53 | 37 | 48 | 45 | 43 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 59 | 51 | 32 | 40 | 41 | 42 | <0.0001 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | |||||||

| g/day | 32 | 23 | 39 | 18 | 21 | 23 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day | 27 | 23 | 35 | 16 | 19 | 26 | 0.0008 |

| Diet drinks | |||||||

| g/day | 43 | 28 | 58 | 25 | 23 | 34 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day | 40 | 28 | 48 | 25 | 22 | 38 | 0.0006 |

| Wine and champagne | |||||||

| g/day | 104 | 89 | 55 | 89 | 82 | 46 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 90 | 86 | 47 | 80 | 75 | 43 | <0.0001 |

| Beer | |||||||

| g/day | 125 | 99 | 100 | 120 | 114 | 79 | 0.0066 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 110 | 98 | 83 | 104 | 105 | 71 | 0.0544 |

| Spirits | |||||||

| g/day | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | <0.0001 |

| Food Group | Diet Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Meat-Eaters | Low Meat-Eaters | Poultry-Eaters | Fish-Eaters | Vegetarians | Vegans | p for Difference b | |

| n = 10,145 | n = 3770 | n = 526 | n = 346 | n = 5156 | n = 532 | ||

| Fruit | |||||||

| g/day | 239 | 255 | 263 | 258 | 247 | 268 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 228 | 272 | 282 | 266 | 260 | 294 | <0.0001 |

| Vegetables | |||||||

| g/day | 296 | 293 | 347 | 333 | 326 | 383 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 288 | 319 | 375 | 349 | 347 | 430 | <0.0001 |

| Potatoes—boiled, mashed or jacket | |||||||

| g/day | 83 | 69 | 71 | 73 | 76 | 80 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 79 | 74 | 73 | 74 | 78 | 84 | <0.0001 |

| Potatoes—fried, roasted | |||||||

| g/day | 25 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 19 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 24 | 21 | 19 | 19 | 22 | 21 | <0.0001 |

| White pasta/noodles | |||||||

| g/day | 34 | 31 | 28 | 34 | 34 | 20 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 33 | 33 | 29 | 35 | 36 | 23 | <0.0001 |

| Wholemeal pasta | |||||||

| g/day | 14 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 28 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 13 | 17 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 30 | <0.0001 |

| Couscous, bulgur wheat | |||||||

| g/day | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 8 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 17 | <0.0001 |

| White rice | |||||||

| g/day | 21 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 15 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 21 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 17 | <0.0001 |

| Brown rice | |||||||

| g/day | 12 | 14 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 23 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 11 | 15 | 21 | 18 | 17 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| Pizza | |||||||

| g/day | 9 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 6 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 6 | <0.0001 |

| White bread | |||||||

| g/day | 19 | 14 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 13 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 18 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 17 | 14 | <0.0001 |

| Brown bread | |||||||

| g/day | 16 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 0.03639 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 15 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 0.0099 |

| Wholemeal bread | |||||||

| g/day | 29 | 32 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 53 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 27 | 32 | 34 | 35 | 38 | 53 | <0.0001 |

| Other bread | |||||||

| g/day | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 11 | <0.0001 |

| Porridge | |||||||

| g/day | 43 | 45 | 48 | 47 | 40 | 48 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 42 | 49 | 53 | 50 | 43 | 53 | <0.0001 |

| Breakfast cereal | |||||||

| g/day | 28 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 28 | 24 | 0.0437 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 26 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 28 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| Cereal bars | |||||||

| g/day | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 0.0002 |

| Chocolate | |||||||

| g/day | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 0.0015 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 0.0006 |

| Cake | |||||||

| g/day | 27 | 25 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 19 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 25 | 25 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 19 | <0.0001 |

| Ice cream | |||||||

| g/day | 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| Milk desserts | |||||||

| g/day | 55 | 49 | 45 | 48 | 53 | 42 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 50 | 50 | 46 | 46 | 52 | 40 | 0.0004 |

| Soya dessert | |||||||

| g/day | 3 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 54 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 3 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 57 | <0.0001 |

| Crisps | |||||||

| g/day | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| Tea | |||||||

| g/day | 507 | 495 | 467 | 512 | 480 | 434 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 499 | 545 | 501 | 542 | 515 | 479 | <0.0001 |

| Coffee | |||||||

| g/day | 289 | 261 | 239 | 251 | 259 | 230 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 286 | 289 | 257 | 265 | 280 | 261 | 0.0004 |

| Fruit smoothie | |||||||

| g/day | 108 | 101 | 108 | 113 | 120 | 135 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 101 | 107 | 112 | 113 | 123 | 145 | <0.0001 |

| Fruit squash | |||||||

| g/day | 67 | 52 | 51 | 48 | 57 | 50 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 63 | 52 | 51 | 47 | 58 | 56 | <0.0001 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | |||||||

| g/day | 27 | 20 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day | 26 | 21 | 15 | 15 | 21 | 29 | <0.0001 |

| Diet drinks | |||||||

| g/day | 55 | 36 | 29 | 31 | 43 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day | 55 | 41 | 34 | 34 | 48 | 19 | <0.0001 |

| Wine and champagne | |||||||

| g/day | 83 | 74 | 64 | 81 | 69 | 43 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 80 | 80 | 68 | 84 | 73 | 47 | <0.0001 |

| Beer | |||||||

| g/day | 25 | 24 | 17 | 28 | 26 | 32 | 0.0020 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 24 | 26 | 18 | 28 | 28 | 35 | <0.0001 |

| Spirits | |||||||

| g/day | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| g/2000 kcal/day a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.0033 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papier, K.; Tong, T.Y.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Fensom, G.K.; Knuppel, A.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Comparison of Major Protein-Source Foods and Other Food Groups in Meat-Eaters and Non-Meat-Eaters in the EPIC-Oxford Cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040824

Papier K, Tong TY, Appleby PN, Bradbury KE, Fensom GK, Knuppel A, Perez-Cornago A, Schmidt JA, Travis RC, Key TJ. Comparison of Major Protein-Source Foods and Other Food Groups in Meat-Eaters and Non-Meat-Eaters in the EPIC-Oxford Cohort. Nutrients. 2019; 11(4):824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040824

Chicago/Turabian StylePapier, Keren, Tammy YN Tong, Paul N Appleby, Kathryn E Bradbury, Georgina K Fensom, Anika Knuppel, Aurora Perez-Cornago, Julie A Schmidt, Ruth C Travis, and Timothy J Key. 2019. "Comparison of Major Protein-Source Foods and Other Food Groups in Meat-Eaters and Non-Meat-Eaters in the EPIC-Oxford Cohort" Nutrients 11, no. 4: 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040824

APA StylePapier, K., Tong, T. Y., Appleby, P. N., Bradbury, K. E., Fensom, G. K., Knuppel, A., Perez-Cornago, A., Schmidt, J. A., Travis, R. C., & Key, T. J. (2019). Comparison of Major Protein-Source Foods and Other Food Groups in Meat-Eaters and Non-Meat-Eaters in the EPIC-Oxford Cohort. Nutrients, 11(4), 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040824