Dietary Intake of Anti-Oxidant Vitamins A, C, and E Is Inversely Associated with Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chinese—A 22-Years Population-Based Prospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

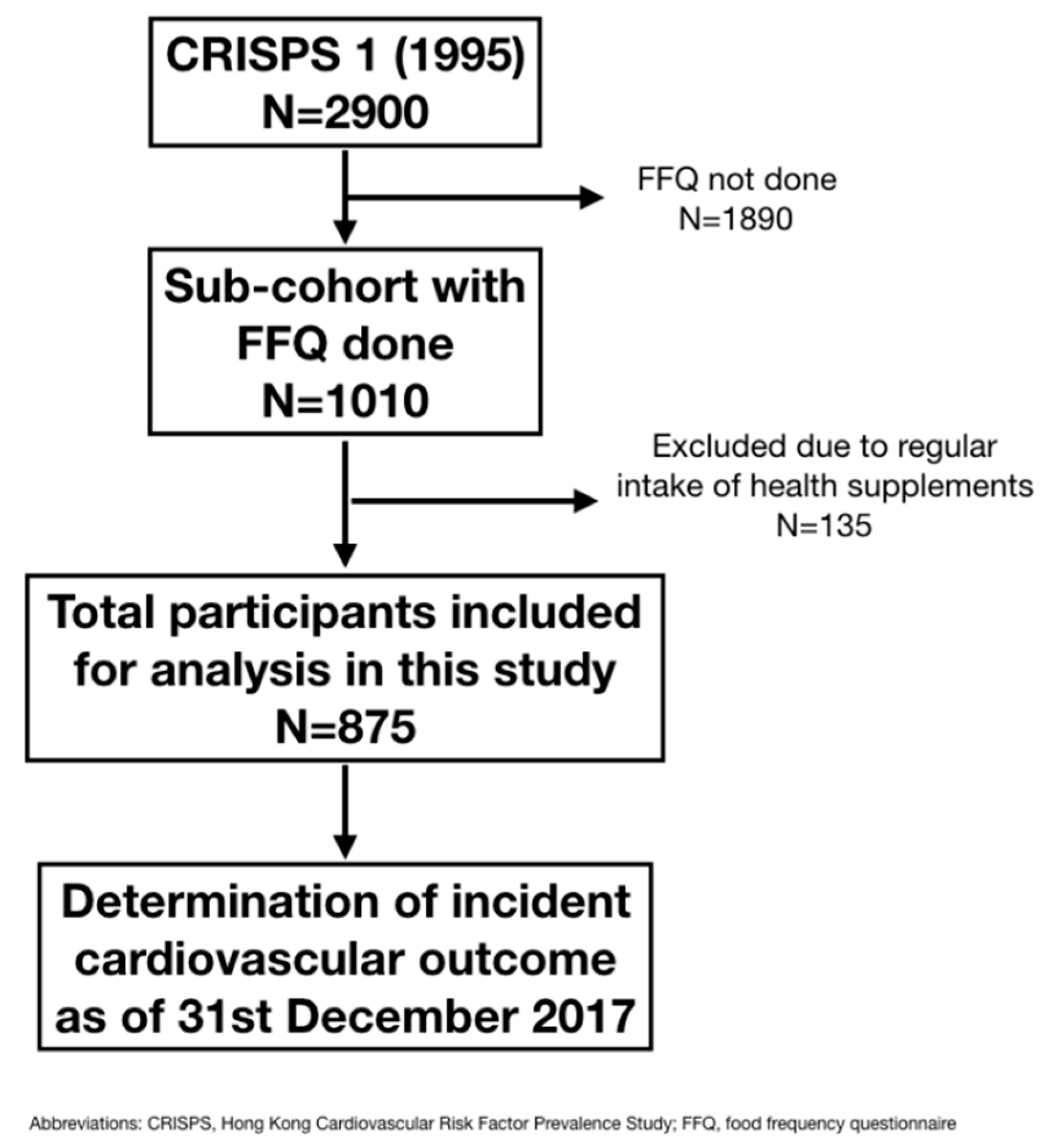

2.1. Participants

2.2. Definitions of Clinical Variables

2.3. Cardiovascular Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

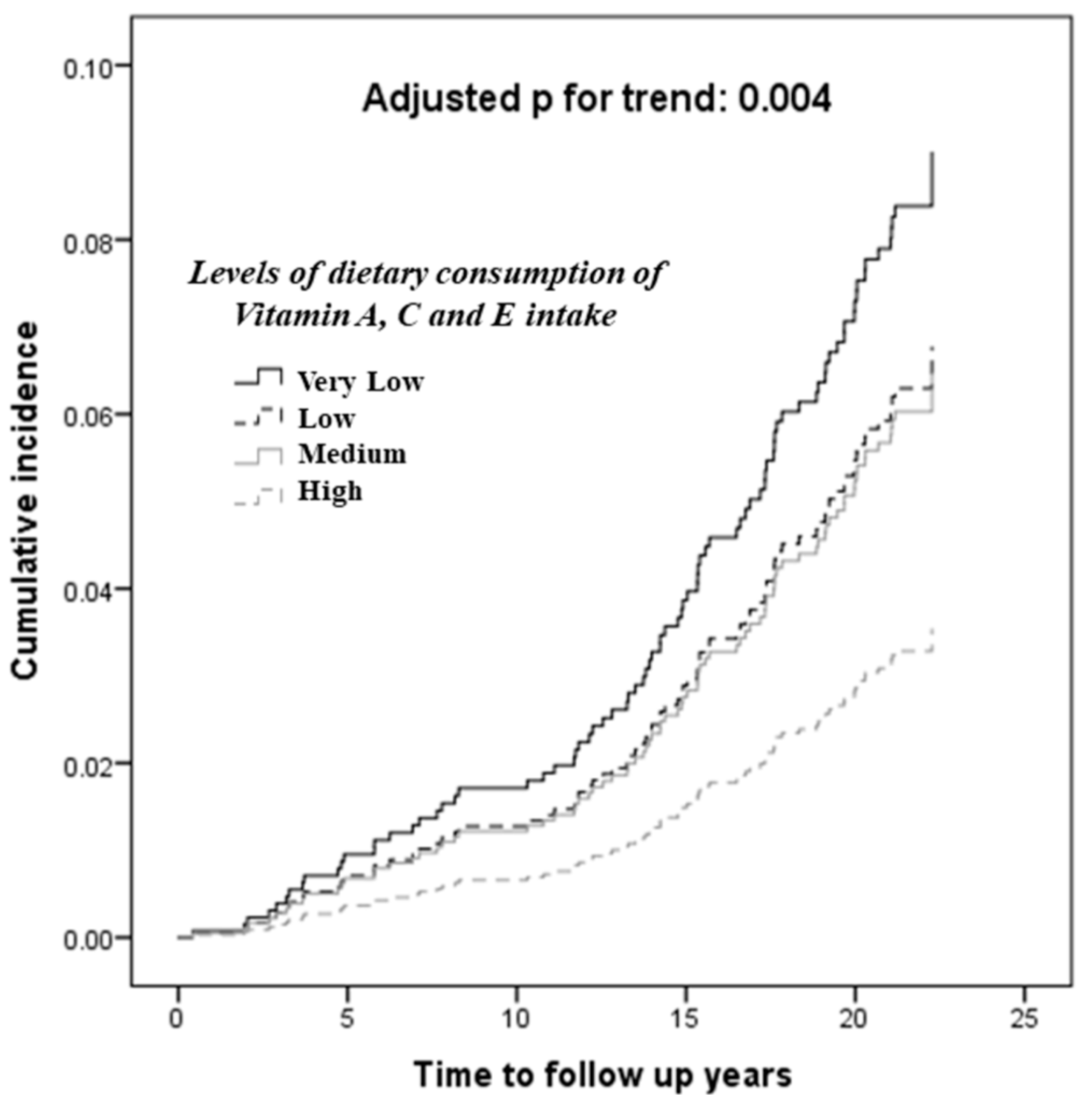

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.; Abajobir, A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.; Ahmed, M.; Aksut, B.; Alam, T.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, L.J.; Goyal, A.; Mehta, C.; Xie, J.; Phillips, L.; Kelkar, A.; Knapper, J.; Berman, D.S.; Nasir, K.; Veledar, E.; et al. 10-year resource utilization and costs for cardiovascular care. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.; Griendling, K.K.; Landmesser, U.; Hornig, B.; Drexler, H. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 91, 7A–11A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Galougahi, K.; Antoniades, C.; Nicholls, S.J.; Channon, K.M.; Figtree, G.A. Redox biomarkers in cardiovascular medicine. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myung, S.K.; Ju, W.; Cho, B.; Oh, S.W.; Park, S.M.; Koo, B.K.; Park, B.J.; Korean Meta-Analysis (KORMA) Study Group. Efficacy of vitamin and antioxidant supplements in prevention of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013, 346, f10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z. Effect of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on cardiovascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esterbauer, H.; Striegl, G.; Puhl, H.; Oberreither, S.; Rotheneder, M.; el-Saadani, M.; Jurgens, G. The role of vitamin E and carotenoids in preventing oxidation of low density lipoproteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1989, 570, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.M.; Qu, Z.C. Ascorbic acid prevents increased endothelial permeability caused by oxidized low density lipoprotein. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 33, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciarelli, R.; Zingg, J.M.; Azzi, A. Vitamin E reduces the uptake of oxidized LDL by inhibiting CD36 scavenger receptor expression in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells. Circulation 2000, 102, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, M.N.; Frei, B.; Vita, J.A.; Keaney, J.F., Jr. Antioxidants and atherosclerotic heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaziano, J.M.; Manson, J.E.; Branch, L.G.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C.; Buring, J.E. A prospective study of consumption of carotenoids in fruits and vegetables and decreased cardiovascular mortality in the elderly. Ann. Epidemiol. 1995, 5, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Geleijnse, J.M.; den Breeijen, J.H.; Boeing, H.; Hofman, A.; Grobbee, D.E.; Witteman, J.C. Dietary antioxidants and risk of myocardial infarction in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.G.; Shu, X.O.; Li, H.L.; Zhang, W.; Gao, J.; Sun, J.W.; Zheng, W.; Xiang, Y.B. Dietary antioxidant vitamins intake and mortality: A report from two cohort studies of Chinese adults in Shanghai. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, Y.; Iso, H.; Date, C.; Kikuchi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Wada, Y.; Inaba, Y.; Tamakoshi, A.; Group, J.S. Dietary intakes of antioxidant vitamins and mortality from cardiovascular disease: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study (JACC) study. Stroke 2011, 42, 1665–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stampfer, M.J.; Hennekens, C.H.; Manson, J.E.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.C. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary disease in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Ascherio, A.; Giovannucci, E.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary heart disease in men. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knekt, P.; Reunanen, A.; Jarvinen, R.; Seppanen, R.; Heliovaara, M.; Aromaa, A. Antioxidant vitamin intake and coronary mortality in a longitudinal population study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 139, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushi, L.H.; Folsom, A.R.; Prineas, R.J.; Mink, P.J.; Wu, Y.; Bostick, R.M. Dietary antioxidant vitamins and death from coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini-Hill, A.; Kawas, C.H.; Corrada, M.M. Antioxidant vitamin intake and mortality: The Leisure World Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 181, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janus, E.D. Epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in Hong Kong. Relationship between dietary intake and the development of type 2 diabetes in a Chinese population: The Hong Kong Dietary Survey. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1997, 24, 987–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Leung, S.S.; Ho, S.C.; Lam, T.H.; Janus, E.D. Dietary intake and practices in the Hong Kong Chinese population. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Heal. 1998, 52, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Woo, J.; Chan, R.; Sham, A.; Ho, S.; Tso, A.; Cheung, B.; Lam, T.H.; Lam, K. Relationship between dietary intake and the development of type 2 diabetes in a Chinese population: The Hong Kong Dietary Survey. Public Heal. Nutr. 2011, 14, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 1998, 15, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Shih, A.Z.; Woo, Y.C.; Fong, C.H.; Leung, O.Y.; Janus, E.; Cheung, B.M.; Lam, K.S. Optimal Cut-Offs of Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) to Identify Dysglycemia and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A 15-Year Prospective Study in Chinese. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1220S–1231S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osganian, S.K.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.; Spiegelman, D.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C. Dietary carotenoids and risk of coronary artery disease in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uesugi, S.; Ishihara, J.; Iso, H.; Sawada, N.; Takachi, R.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S. Dietary intake of antioxidant vitamins and risk of stroke: The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsen, E.R. Dietary reference intakes for the antioxidant nutrients: Vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.B.; Min, J.Y. Relation of serum vitamin A levels to all-cause and cause-specific mortality among older adults in the NHANES III population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Folsom, A.R.; Harnack, L.; Halliwell, B.; Jacobs, D.R. Does supplemental vitamin C increase cardiovascular disease risk in women with diabetes? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Lifestyle management: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, S38–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Sheehy, T.; Kolonel, L. Sources of vegetables, fruits and vitamins A, C and E among five ethnic groups: Results from a multiethnic cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Su, C.; Du, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.; Huang, F.; Ouyang, Y.; et al. Food sources and potential determinants of dietary vitamin C intake in Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.; Janus, E.D.; Strain, J.J. Plasma ascorbate and vitamin E levels in Hong Kong Chinese. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 52, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V.; Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; Zhang, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Dagenais, G.; Gupta, R.; Mohan, V.; Lear, S.; et al. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Mozaffarian, D. Global, regional and national consumption of major food groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V.; Yusuf, S.; Chow, C.K.; Dehghan, M.; Corsi, D.J.; Lock, K.; Popkin, B.; Rangarajan, S.; Khatib, R.; Lear, S.A.; et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2016, 4, e695–e703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Variables | All | Adverse Cardiovascular Events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-Value | ||

| N, % | 875 | 790 | 85 | -- |

| Age, years | 44.7 ± 11.5 | 43.7 ± 10.1 | 54.1 ± 11.5 | <0.001 |

| Men, % | 52.1 | 49.7 | 74.1 | <0.001 |

| Ever smokers, % | 25.5 | 22.7 | 51.8 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.3 ± 3.63 | 24.2 ± 3.61 | 25.4 ± 3.69 | 0.005 |

| Waist circumference, cm | ||||

| Men | 83.2 ± 9.46 | 82.6 ± 9.16 | 87.2 ± 10.4 | <0.001 |

| Women | 76.0 ± 9.70 | 75.6 ± 9.61 | 82.9 ± 8.83 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 17.3 | 14.8 | 40.0 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 119 ± 18.5 | 118 ± 17.8 | 130 ± 21.1 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 75.0 ± 11.0 | 74.4 ± 10.7 | 80.6 ± 12.0 | <0.001 |

| Dysglycemia, % | 9.7 | 7.1 | 14.1 | 0.025 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 5.36 ± 1.15 | 5.30 ± 0.99 | 5.88 ± 2.06 | <0.001 |

| 2-h glucose, mmol/L | 6.65 ± 3.21 | 6.53 ± 2.95 | 7.72 ± 4.87 | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 61.4 | 59.6 | 77.6 | 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.28 ± 0.36 | 1.29 ± 0.35 | 1.18 ± 0.30 | 0.003 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 3.26 ± 0.87 | 3.21 ± 0.84 | 3.73 ± 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides *, mmol/L | 1.0 (0.70–1.40) | 1.0 (0.70–1.40) | 1.1 (0.90–1.56) | 0.009 |

| History of CVD at baseline, % | 2.6 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 0.007 |

| Urinary sodium *, mg/day | 3953 (2494–5566) | 3958 (2531–5558) | 3884 (2386–6080) | 0.612 |

| Urinary potassium *, mg/day | 2523 (1941–3488) | 2629 (1967–3518) | 2466 (1733–3418) | 0.389 |

| All | Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Cardiovascular Events | Adverse Cardiovascular Events | ||||

| Baseline variables | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| N | 875 | 393 | 63 | 397 | 22 |

| Energy, kcal | 2030 (1671–2481) | 2535 (1983–2781) | 2168 (1807–2584) | 1743 (1481–2073) | 1696 (1413–1916) |

| Protein, g | 92.1 (73.2–118) | 106 (84.5–132) | 96.7 (75.1–117.7) | 80.9 (65.2–101) | 81.1 (61.4–103) |

| Fat, g | 64.7 (49.2–83.1) | 74.2 (59.2–117.7) | 61.3 (48.8–89.1) | 55.8 (44.4–70.4) | 50.4 (40.8–64.3) |

| Carbohydrate, g/day | 268 (221–335) | 317 (261–369) | 287 (244–377) | 233 (191–278) | 227 (198–256) |

| Vitamin A, IU/day | 3907 (2584–5758) | 3966 (2607–5711) | 3411 (2070–5310) | 4015 (2731–5987) | 3117 (2044–5436) |

| Vitamin B1, mg/day | 0.95 (0.72–1.22) | 1.08 (0.85–1.38) | 0.97 (0.75–1.35) | 0.83 (0.66–1.06) | 0.78 (0.64–0.65) |

| Vitamin B2, mg/day | 1.05 (0.79–1.32) | 1.15 (0.91–1.46) | 1.03 (0.82–1.27) | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) | 0.91 (0.67–1.25) |

| Niacin, mg/day | 16.8 (12.9–21.7) | 19.0 (14.9–24.0) | 16.9 (13.5–22.1) | 14.8 (11.5–18.8) | 14.5 (12.1–19.7) |

| Vitamin C, mg/day | 141.7 (95.9–199) | 132 (84.8–186) | 116 (58.0–180) | 153 (110–220) | 129 (96.7–188) |

| Vitamin D, ug/day | 10.1 (5.00–20.4) | 13.0 (5.21–25.0) | 12.4 (5.53–21.5) | 9.00 (5.00–15.0) | 6.06 (4.69–10.2) |

| Vitamin E, mg/day | 9.88 (7.53–13.0) | 10.0 (7.77–13.7) | 9.91 (6.29–12.6) | 9.65 (7.54–12.4) | 9.64 (5.34–13.2) |

| Calcium, mg/day | 537 (412–697) | 558 (430–728) | 517 (382–655) | 529 (398–691) | 439 (348–671) |

| Phosphorus, mg/day | 1078 (853–1322) | 1217 (992–1459) | 1101 (883–1299) | 954 (772–1139) | 925 (703–1100) |

| Iron, mg/day | 15.3 (11.9–19.0) | 16.6 (13.2–20.6) | 15.1 (11.7–18.8) | 13.7 (11.0–17.7) | 14.2 (10.1–18.3) |

| Zinc, mg/day | 11.2 (8.84–14.6) | 13.0 (10.7–16.4) | 12.3 (9.21–15.6) | 9.63 (7.88–12.0) | 10.0 (6.95–12.5) |

| Iodine, ug/day | 0.21 (0.00–0.61) | 0.21 (0.00–0.71) | 0.04 (0.00–0.55) | 0.21 (0.00–0.66) | 0.16 (0.00–0.32) |

| Copper, mg/day | 12.1 (8.90–15.5) | 12.9 (9.67–16.3) | 10.1 (8.0.–15.3) | 11.4 (8.85–14.5) | 10.0 (7.11–13.4) |

| Fibre, g/day | 7.54 (5.61–9.98) | 7.29 (5.236–9.88) | 6.79 (4.33–9.57) | 7.92 (6.09–10.1) | 6.21 (4.74–9.07) |

| SFA, g/day | 17.2 (12.7–23.2) | 20.6 (15.5–26.5) | 17.7 (12.5–26.3) | 15.1 (11.1–19.8) | 14.0 (11.0–17.0) |

| MUFA, g/day | 21.8 (16.5–29.8) | 26.3 (20.1–33.8) | 22.0 (16.1–32.7) | 19.3 (14.6–24.1) | 18.3 (14.1–21.3) |

| PUFA, g/day | 14.4 (11.3–18.1) | 16.1 (12.8–20.2) | 13.7 (11.1–18.7) | 12.8 (10.7–15.6) | 11.7 (8.02–15.7) |

| Cholesterol, mg/day | 307 (225–426) | 368 (263–505) | 343 (226–450) | 267 (193–363) | 240 (178–278) |

| Protein, % energy/day | 18.6 ± 3.12 | 18.4 ± 3.00 | 17.8 ± 2.87 | 18.8 ± 3.22 | 19.5 ± 3.36 |

| Carbohydrate, % energy/day | 53.5 ± 7.67 | 53.5 ± 7.60 | 54.9 ± 9.16 | 53.3 ± 7.53 | 53.3 ± 6.51 |

| Fat, % energy/day | 28.9 ± 5.58 | 28.7 ± 5.57 | 27.9 ± 6.97 | 29.2 ± 5.39 | 28.4 ± 4.18 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95%CI) | p-Value | |

| Protein, g/day | 1.29 (0.53–3.12) | 0.57 | 1.13 (0.47–2.73) | 0.79 |

| Fat, g/day | 1.34 (0.66–2.73) | 0.42 | 1.30 (0.64–2.64) | 0.47 |

| Carbohydrate, g/day | 0.48 (0.17–1.37) | 0.17 | 0.57 (0.20–1.60) | 0.29 |

| Vitamin A, IU/day | 0.67 (0.53–0.86) | 0.002 | 0.68 (0.53–0.88) | 0.003 |

| Vitamin B1, mg/day | 1.05 (0.58–1.89) | 0.87 | 1.01 (0.56–1.84) | 0.96 |

| Vitamin B2, mg/day | 0.75 (0.42–1.34) | 0.34 | 0.64 (0.36–1.16) | 0.14 |

| Niacin, mg/day | 1.21 (0.66–2.25) | 0.54 | 1.08 (0.58–2.02) | 0.80 |

| Vitamin C, mg/day | 0.66 (0.51–0.84) | 0.001 | 0.66 (0.52–0.85) | 0.001 |

| Vitamin D, ug/day | 1.10 (0.95–1.27) | 0.20 | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.36 |

| Vitamin E, mg/day | 0.60 (0.41–0.90) | 0.012 | 0.57 (0.38–0.86) | 0.007 |

| Calcium, mg/day | 0.71 (0.46–1.09) | 0.11 | 0.71 (0.45–1.10) | 0.12 |

| Phosphorus, mg/day | 0.93 (0.36–2.38) | 0.88 | 0.81 (0.31–2.12) | 0.66 |

| Iron, mg/day | 0.55 (0.29–1.07) | 0.08 | 0.54 (0.28–1.06) | 0.07 |

| Zinc, mg/day | 1.50 (0.87–2.59) | 0.15 | 1.32 (0.77–2.25) | 0.31 |

| Iodine, ug/day | 0.94 (0.65–1.37) | 0.75 | 0.94 (0.64–1.37) | 0.73 |

| Copper, mg/day | 0.67 (0.51–0.89) | 0.005 | 0.69 (0.52–0.91) | 0.008 |

| Fiber, g/day | 0.52 (0.37–0.75) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.37–0.77) | 0.001 |

| SFA, g/day | 1.64 (0.95–2.82) | 0.08 | 1.69 (0.96–2.98) | 0.07 |

| MUFA, g/day | 1.58 (0.87–2.85) | 0.13 | 1.60 (0.87–2.94) | 0.13 |

| PUFA, g/day | 0.85 (0.46–1.59) | 0.62 | 0.86 (0.46–1.61) | 0.64 |

| Cholesterol, mg/day | 1.41 (0.92–2.17) | 0.11 | 1.40 (0.89–2.19) | 0.14 |

| Protein, % energy/day | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 0.54 | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.73 |

| Carbohydrate, % energy/day | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.15 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.19 |

| Fat, % energy/day | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.21 | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.22 |

| Q1 (Lowest Intake) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (Highest Intake) | p-Trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A, IU/day | Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.55 (0.31–0.97) | 0.58 (0.32–1.07) | 0.45 (0.24–0.83) | 0.014 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.55 (0.31–0.97) | 0.58 (0.32–1.06) | 0.45 (0.25–0.84) | 0.014 * | |

| Vitamin C, mg/day | Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.13 (0.65–1.98) | 0.69 (0.39–1.24) | 0.37 (0.18–0.73) | 0.002 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.16 (0.66–2.02) | 0.71 (0.40–1.27) | 0.38 (0.19–0.74) | 0.002 * | |

| Vitamin E, mg/day | Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.38–1.19) | 0.51 (0.28–0.93) | 0.57 (0.31–1.04) | 0.035 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.39–1.20) | 0.51 (0.28–0.94) | 0.59 (0.33–1.08) | 0.046 * |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.-H.; Chan, R.S.M.; Wan, H.Y.L.; Woo, Y.-C.; Cheung, C.Y.Y.; Fong, C.H.Y.; Cheung, B.M.Y.; Lam, T.-H.; Janus, E.; Woo, J.; et al. Dietary Intake of Anti-Oxidant Vitamins A, C, and E Is Inversely Associated with Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chinese—A 22-Years Population-Based Prospective Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111664

Lee C-H, Chan RSM, Wan HYL, Woo Y-C, Cheung CYY, Fong CHY, Cheung BMY, Lam T-H, Janus E, Woo J, et al. Dietary Intake of Anti-Oxidant Vitamins A, C, and E Is Inversely Associated with Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chinese—A 22-Years Population-Based Prospective Study. Nutrients. 2018; 10(11):1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111664

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Chi-Ho, Ruth S. M. Chan, Helen Y. L. Wan, Yu-Cho Woo, Chloe Y. Y. Cheung, Carol H. Y. Fong, Bernard M. Y. Cheung, Tai-Hing Lam, Edward Janus, Jean Woo, and et al. 2018. "Dietary Intake of Anti-Oxidant Vitamins A, C, and E Is Inversely Associated with Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chinese—A 22-Years Population-Based Prospective Study" Nutrients 10, no. 11: 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111664

APA StyleLee, C.-H., Chan, R. S. M., Wan, H. Y. L., Woo, Y.-C., Cheung, C. Y. Y., Fong, C. H. Y., Cheung, B. M. Y., Lam, T.-H., Janus, E., Woo, J., & Lam, K. S. L. (2018). Dietary Intake of Anti-Oxidant Vitamins A, C, and E Is Inversely Associated with Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chinese—A 22-Years Population-Based Prospective Study. Nutrients, 10(11), 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111664