Deep Learning-Based Diffraction Identification and Uncertainty-Aware Adaptive Weighting for GNSS Positioning in Occluded Environments

Highlights

- A deep learning-based diffraction identification method using LSTM is proposed, where the multi-feature fusion of “SNR + Elevation + Azimuth” achieves optimal recognition accuracy (84.28%).

- An uncertainty-aware adaptive weighting strategy is developed by introducing information entropy, which effectively suppresses diffraction errors while retaining ambiguous signals with conservative weights.

- The proposed framework significantly improves GNSS positioning reliability in high-occlusion environments, increasing the AFR to 99.9% and enhancing the positioning accuracy in the horizontal and vertical directions by 80.1% and 76.4%.

- This study provides a robust solution for deformation monitoring in complex terrains by replacing rigid thresholding with intelligent, continuous weight adjustment.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

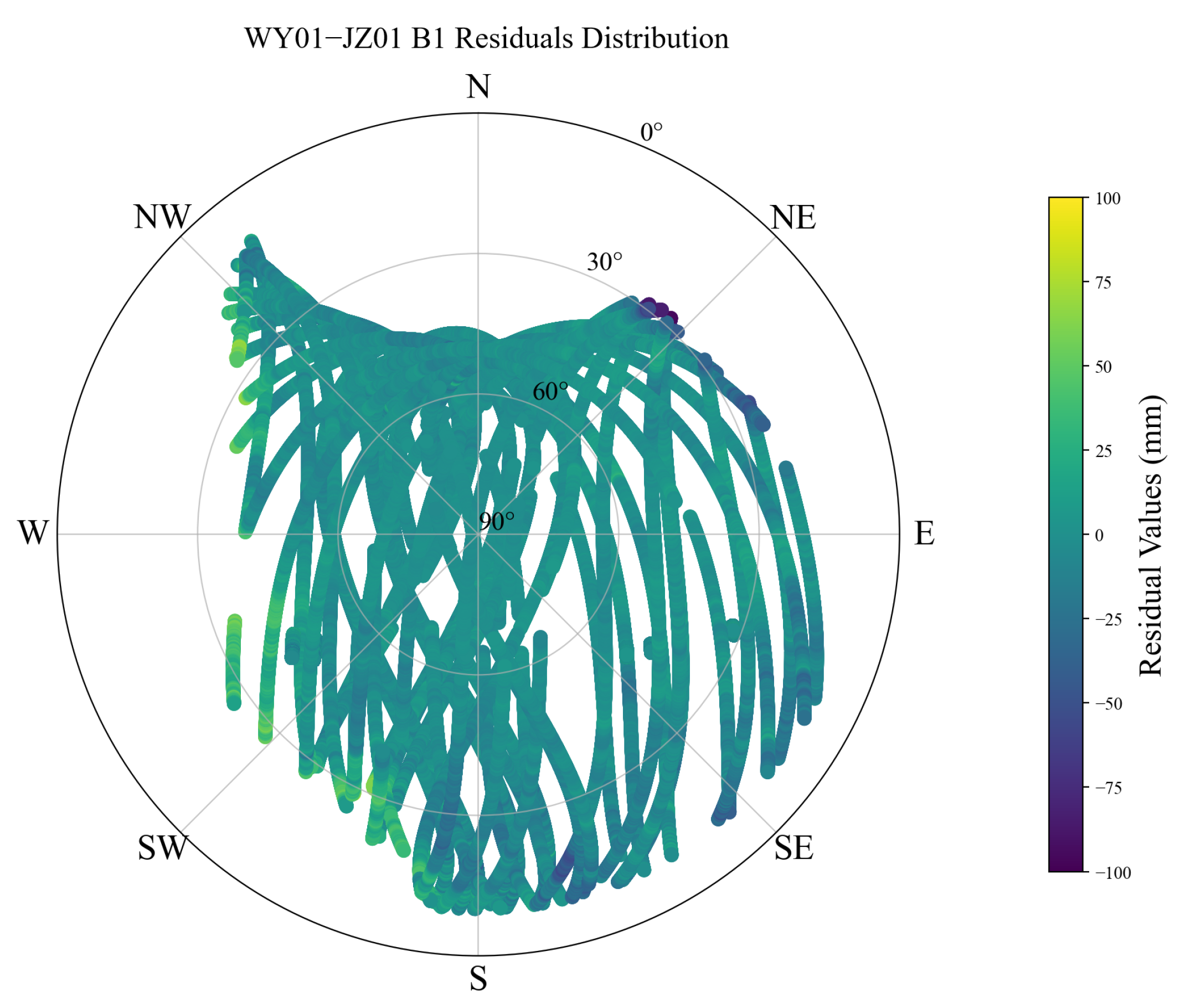

2.1. Diffraction Error Extraction

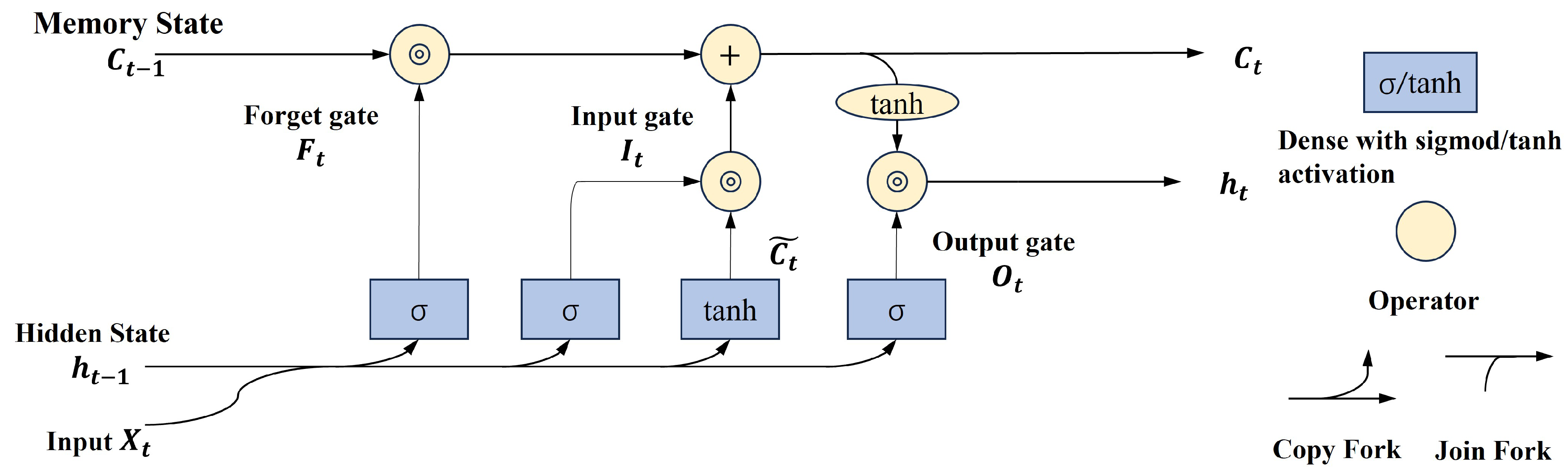

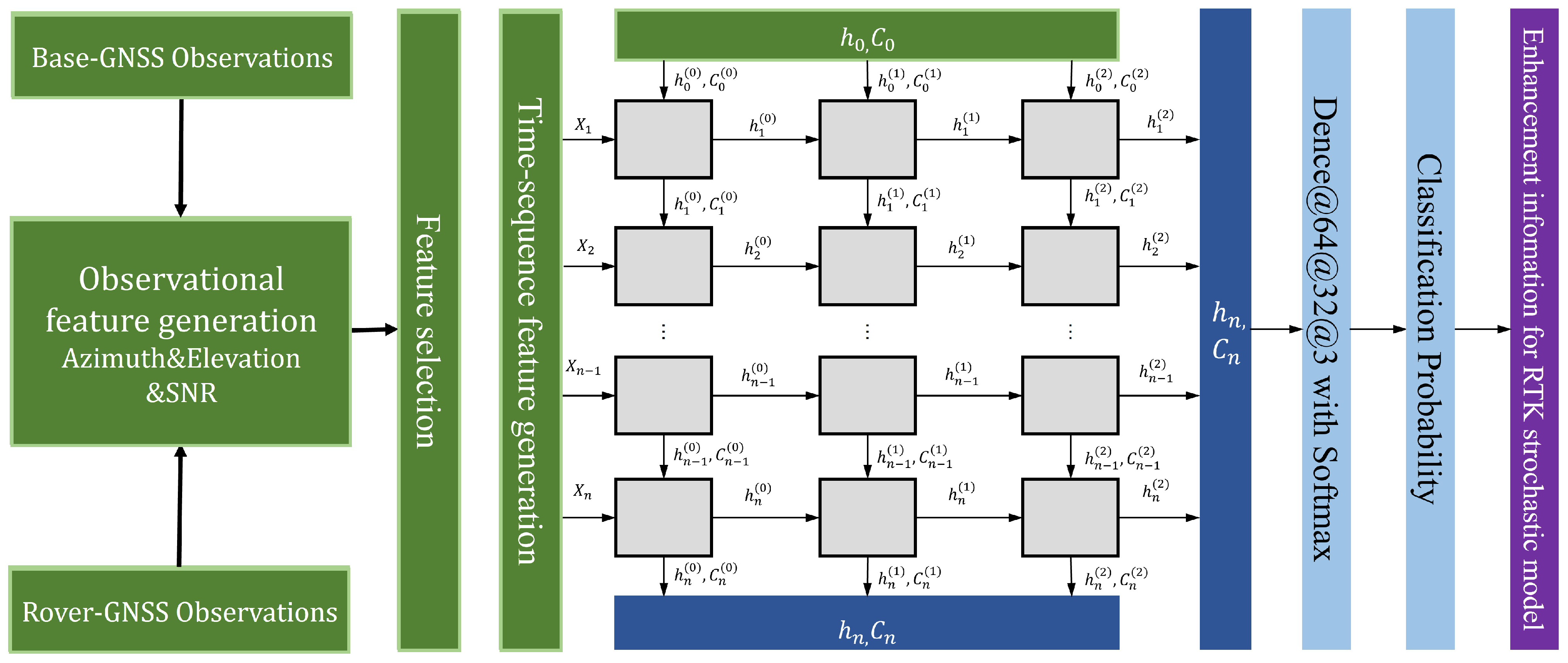

2.2. Machine Learning Methods

2.3. Adaptive Weighting Method for Diffraction Mitigation Based on Uncertainty Quantification

3. Results and Discussion

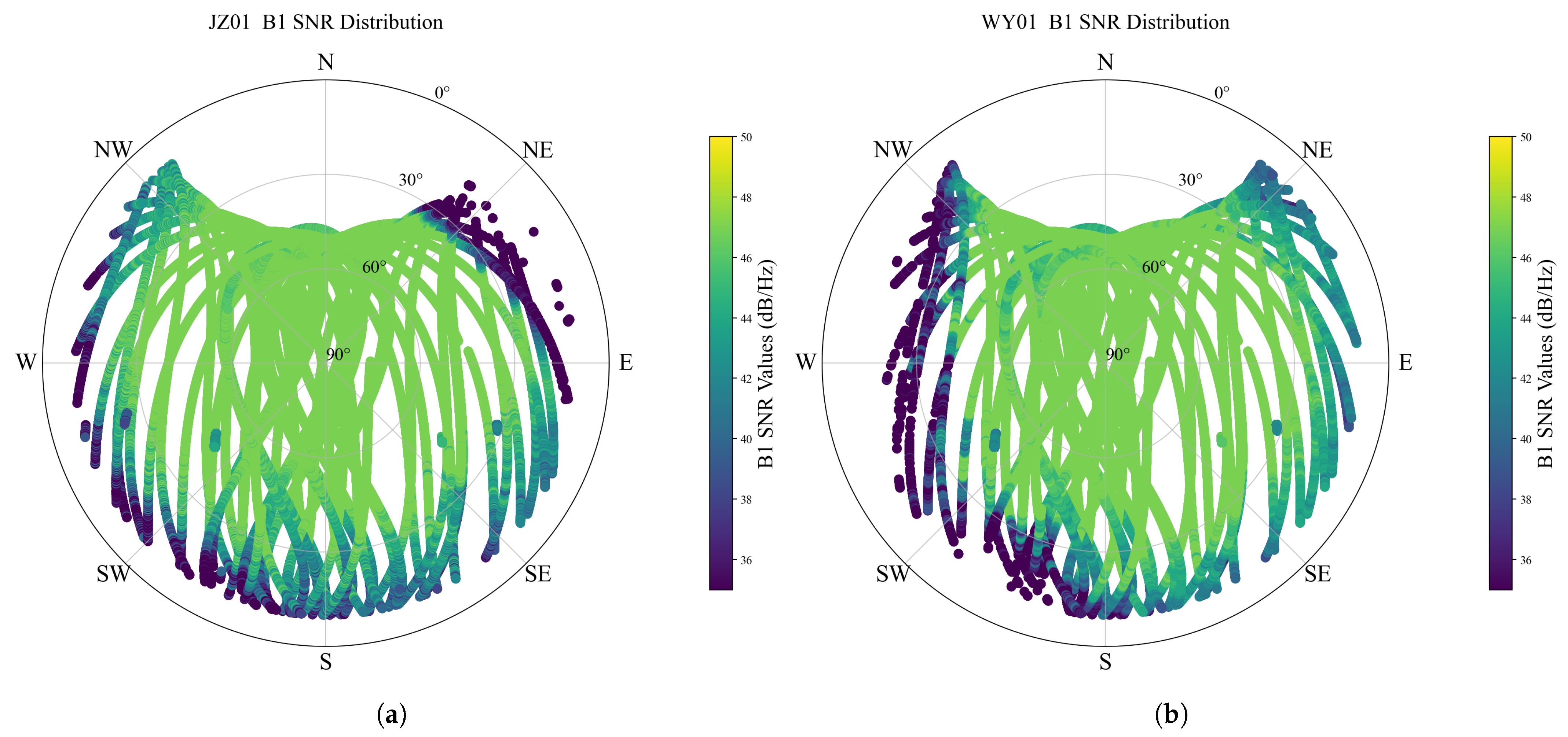

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Diffraction Error Elimination Based on Deep Learning

3.3. Performance of Diffraction Error Elimination

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFR | Ambiguity Fixing Rate |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DD | Double-Difference |

| DNN | Deep Neural Networks |

| GF | Geometry-Free |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite Systems |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HMW | Hatch-Melbourne-Wübbena |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MHM | Multipath Hemispherical Map |

| NLOS | Non-Line-of-Sight |

| OMC | Observed-minus-Computed |

| PDOP | Position Dilution of Precision |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| SD | Single-Difference |

| SF | Sidereal Filtering |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| VDOP | Vertical Dilution of Precision |

References

- Duong, T.T.; Long, N.Q.; Van Duc, B. Hybrid-Precision GNSS Positioning Strategies for Landslide Monitoring. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qian, C.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Liu, H. Tightly coupled integration of vector HD map, LiDAR, GNSS, and INS for precise vehicle navigation in GNSS-challenging environment. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 1341–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qian, C.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Liu, H. A LiDAR–INS-aided geometry-based cycle slip resolution for intelligent vehicle in urban environment with long-term satellite signal loss. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheimy, N.; Lari, Z. GNSS Applications in Surveying and Mobile Mapping. In Position, Navigation, and Timing Technologies in the 21st Century: Integrated Satellite Navigation, Sensor Systems, and Civil Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 1711–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Xi, R.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Li, L. Review of bridge structural health monitoring based on GNSS: From displacement monitoring to dynamic characteristic identification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 80043–80065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Shu, B.; Li, X.; Tian, Y. Research progress and prospects of GNSS deformation monitoring technology for landslide hazards. Navig. Position. Timing 2023, 10, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, T.; Guan, M.; Gao, F.; Jiang, N. LEO-constellation-augmented multi-GNSS real-time PPP for rapid re-convergence in harsh environments. GPS Solut. 2022, 26, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hwang, S.H. Improved GNSS Positioning Schemes in Urban Canyon Environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 112354–112367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Petovello, M.G. Measuring GNSS multipath distributions in urban canyon environments. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014, 64, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Xi, R.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, D.; Jiang, W. Analysis and elimination of GNSS carrier phase diffraction error in high occlusion environments. Measurement 2025, 253, 117809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Gan, X.; Yu, B.; Zhang, J. Precise point positioning algorithm for pseudolite combined with GNSS in a constrained observation environment. Sensors 2020, 20, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Li, B. A composite stochastic model considering the terrain topography for real-time GNSS monitoring in canyon environments. J. Geod. 2022, 96, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Du, S.; Wang, D. GNSS techniques for real-time monitoring of landslides: A review. Satell. Navig. 2023, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, Y.; Huang, G.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q. Mitigating GNSS multipath in landslide areas: A novel approach considering mutation points at different stages. Landslides 2023, 20, 2497–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Zhong, S. A satellite orbit maneuver detection and robust multipath mitigation method for GPS coordinate time series. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 2784–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Chen, W.; Dong, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Peng, Y.; Yu, C. Multipath mitigation in GNSS precise point positioning based on trend-surface analysis and multipath hemispherical map. GPS Solut. 2021, 25, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Dong, D.; Wang, M.; Cai, M.; Yu, C.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, M. Multipath mitigation based on trend surface analysis applied to dual-antenna receiver with common clock. GPS Solut. 2019, 23, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-T.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. NLOS correction/exclusion for GNSS measurement using RAIM and city building models. Sensors 2015, 15, 17329–17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Li, T.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, C.; Wang, C.; Duan, R.; Meng, F.; Xiang, Y.; Pei, L. SVA: A Street-View-Aided GNSS Positioning Framework with 2DSDM and Likelihood Road for NLOS/Multipath Mitigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 8131–8138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, J.; Berbineau, M.; Heddebaut, M. Land mobile GNSS availability and multipath evaluation tool. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2005, 54, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D.; Kleiner, A. Improved GPS sensor model for mobile robots in urban terrain. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 4385–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, F.; Eling, C.; Kuhlmann, H. Empirical assessment of obstruction adaptive elevation masks to mitigate site-dependent effects. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 1695–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Matsuo, K.; Amano, Y. Rotating GNSS antennas: Simultaneous LOS and NLOS multipath mitigation. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Ding, X.; Zhu, J. Single reflected or diffracted signal error elimination method in GPS dynamic deformation monitoring. J. Geotech. Invest. Surv. 2006, 34, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.L.; Ding, X. Mitigation of GPS signal diffraction effect for deformation applications based on environment modelling. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2005, 34, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, R.; Xu, D.; Jiang, W.; He, Q.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Q.; Fan, X. Elimination of GNSS carrier phase diffraction error using an obstruction adaptive elevation masks determination method in a harsh observing environment. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Han, L.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, W.; Meng, X.; An, X.; Xuan, W. Numerical modeling and analysis of GNSS carrier-phase diffraction error in occlusion environments. J. Geod. 2025, 99, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Tu, R.; Lu, X.; Xia, X.; Zhang, R.; Fan, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, S. An elevation mask modeling method based on azimuth rounding for monitoring building deformation. Acta Geod. Geophys. 2023, 58, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, G.; Geng, J.; Wang, F.; Li, P. Multipath hemispherical map model with geographic cut-off elevation constraints for real-time GNSS monitoring in complex environments. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhang, G.; Yang, B.; Hsu, L.-T. Machine learning in GNSS multipath/NLOS mitigation: Review and benchmark. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2024, 39, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ma, S.; Zhou, H.; Du, C.; Li, S. Measurement and statistical analysis of distinguishable multipaths in underground tunnels. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2020, 2020, 2501832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Jia, Z.; Lai, L.; Shen, Y. An efficient GNSS NLOS signal identification and processing method using random forest and factor analysis with visual labels. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, G.; Susi, M.; Fortuny-Guasch, J.; Bonavitacola, F. An experimental analysis of GNSS signals to characterize the propagation environment by means of machine learning processing. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Information and Telecommunication Technologies and Radio Electronics (UkrMiCo), Odesa, Ukraine, 29 November–3 December 2021; pp. 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhang, G.; Yang, B.; Hsu, L.-T. PositionNet: CNN-based GNSS positioning in urban areas with residual maps. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 148, 110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Dai, Z.; Li, T.; Zhu, X. GNSS NLOS signals identification based on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Science, Electrical, and Automation Engineering (ISEAE 2022), Hangzhou, China, 25–27 March 2022; Volume 12257, pp. 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhai, C.; Xie, T.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, X. GNSS positioning enhancement based on NLOS signal detection using spatio-temporal learning in urban canyons. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Zeng, K.; Yuan, R.; Xie, S.; Niyato, D. Multivariate Time Series Learning for GNSS NLOS Intelligent Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 25001–25018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, R. The synergism of GPS code and carrier measurements. Int. Geod. Symp. Satell. Doppler Position. 1983, 2, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Melbourne, W.G. The case for ranging in GPS-based geodetic systems. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Precise Positioning with the Global Positioning System, Rockville, MD, USA, 15–19 April 1985; pp. 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wübbena, G. Software developments for geodetic positioning with GPS using TI4100 code and carrier measurements. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Precise Positioning with the Global Positioning System, Rockville, MD, USA, 15–19 April 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Sun, A.; Meng, X.; Zhao, D.; Hancock, C. GNSS carrier-phase multipath modeling and correction: A review and prospect of data processing methods. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; El-Sheimy, N. Machine learning based GNSS signal classification and weighting scheme design in the built environment: A comparative experiment. Measurement 2021, 182, 109696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2016; Volume 48, pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Gao, Y. A new asynchronous RTK method to mitigate base station observation outages. Sensors 2019, 19, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | AFR (%) | RMS (m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | U | ||

| Cut-off Elevation | 98.5 | 0.2954 | 0.2319 | 1.1932 |

| SNR Weighing | 98.0 | 0.3345 | 0.3095 | 1.1991 |

| SNR Mask 35 dB-Hz | 98.0 | 0.3343 | 0.2989 | 1.1706 |

| SNR Mask 40 dB-Hz | 97.7 | 0.3511 | 0.2912 | 1.3270 |

| SNR Mask 45 dB-Hz | 98.5 | 0.2522 | 0.2443 | 1.2913 |

| Our Method | 99.9 | 0.0265 | 0.0787 | 0.2920 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Shen, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Qian, C. Deep Learning-Based Diffraction Identification and Uncertainty-Aware Adaptive Weighting for GNSS Positioning in Occluded Environments. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010158

Wang C, Shen H, Liu Y, Meng Q, Qian C. Deep Learning-Based Diffraction Identification and Uncertainty-Aware Adaptive Weighting for GNSS Positioning in Occluded Environments. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010158

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chenhui, Haoliang Shen, Yanyan Liu, Qingjia Meng, and Chuang Qian. 2026. "Deep Learning-Based Diffraction Identification and Uncertainty-Aware Adaptive Weighting for GNSS Positioning in Occluded Environments" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010158

APA StyleWang, C., Shen, H., Liu, Y., Meng, Q., & Qian, C. (2026). Deep Learning-Based Diffraction Identification and Uncertainty-Aware Adaptive Weighting for GNSS Positioning in Occluded Environments. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010158