MFEF-YOLO: A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in Aerial Imagery over Open Water

Highlights

- The proposed MFEF-YOLO delivers superior performance for maritime object detection, demonstrating marked improvements of 0.11 and 0.03 in mAP50 for the SeaDronesSee and TPDNV datasets, respectively, alongside an 11.54% reduction in parameters.

- The novel DBSPPF and IMFFNet modules demonstrate superior capability in enhancing multi-scale feature extraction and fusion, significantly boosting detection accuracy for small and densely distributed objects in complex open-water environments.

- This work provides a practical solution for accurate real-time object detection using resource-constrained UAV platforms, enhancing their capability in maritime surveying, monitoring, and search-and-rescue operations.

- The newly constructed TPDNV benchmark dataset, comprising over 120,000 annotated instances of dense small targets, establishes a challenging and valuable resource for advancing the field of small-object detection in remote sensing applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

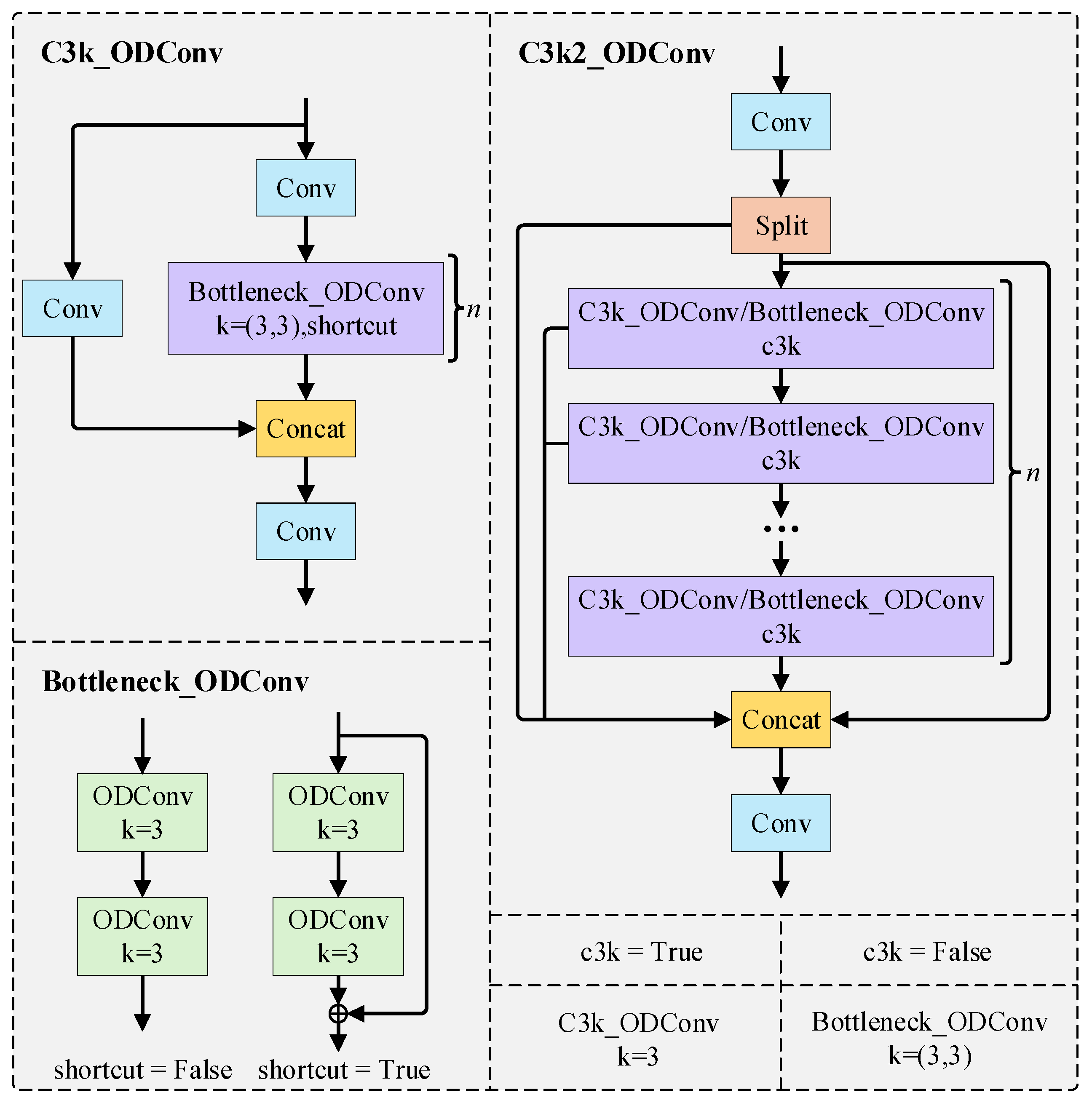

- In the backbone network, we propose a plug-and-play DBSPPF module. This module employs a dual-branch architecture to enhance multi-scale feature utilization and feature extraction capability, enabling the model to detect objects of varying sizes with higher accuracy. Furthermore, we incorporate depthwise separable convolution into this module to significantly improve detection speed. Additionally, we integrate ODConv into the C3k2 module, constructing an enhanced C3k2_ODConv module that not only strengthens feature extraction but also reduces computational overhead.

- (2)

- In the head network, we introduce a 160 × 160 high-resolution detection head specifically for tiny objects while eliminating the 20 × 20 low-resolution head for large objects. This architectural modification significantly enhances small object detection capability in aerial imagery while reducing model parameters by 25%.

- (3)

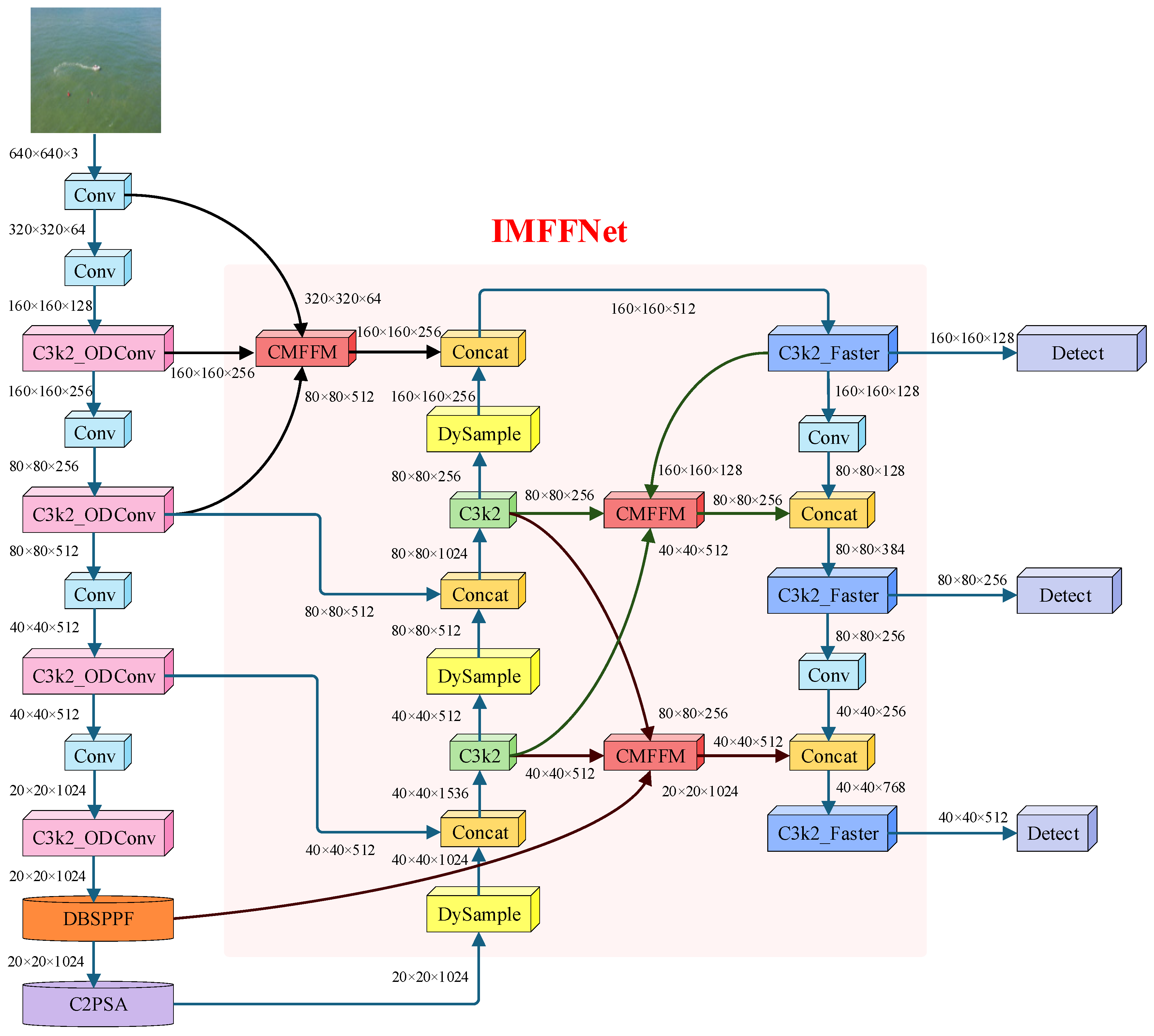

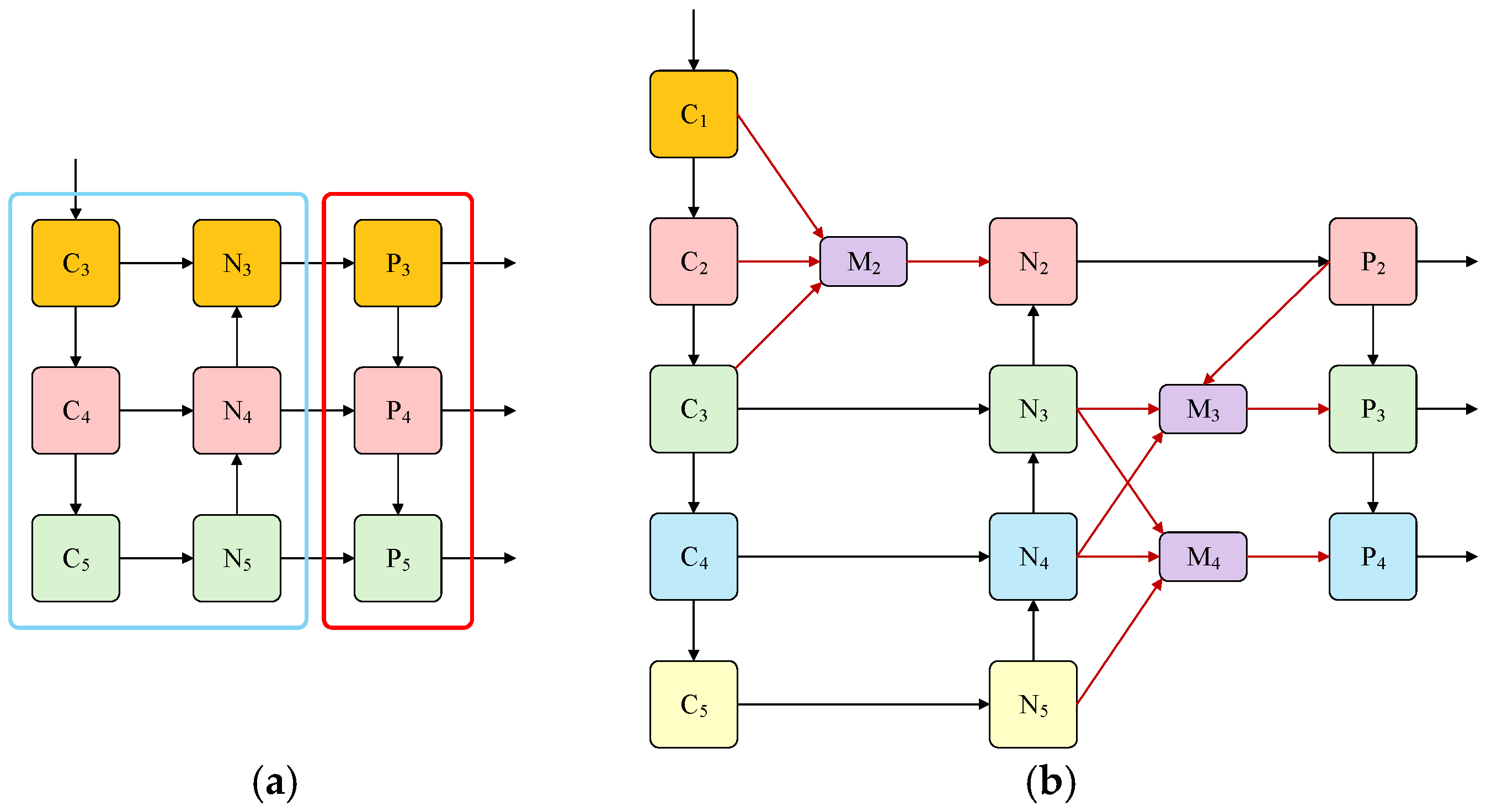

- For the neck network, we propose IMFFNet, an innovative feature fusion network that incorporates three core modules: the C3k2_Faster module enhances network learning capacity and computational efficiency while reducing computational redundancy and memory access; the DySample module preserves richer informative features from high-resolution feature maps; and the CMFFM effectively integrates multi-scale features to improve complex scene understanding and multi-scale object detection performance. This architecture significantly boosts detection performance and adaptability to targets of various sizes.

- (4)

- We construct TPDNV, a novel small-object benchmark dataset comprising 120,822 annotated instances, where the majority are small and densely distributed targets. This dataset establishes a challenging benchmark for evaluating small-object detection models in open waters, with particular emphasis on high-density small target recognition scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Object Detection

2.2. Detection of Small Targets in Open Water

2.3. Applications of SPPF Module in Object Detection

2.4. Applications of Feature Fusion in Object Detection

3. Proposed Method

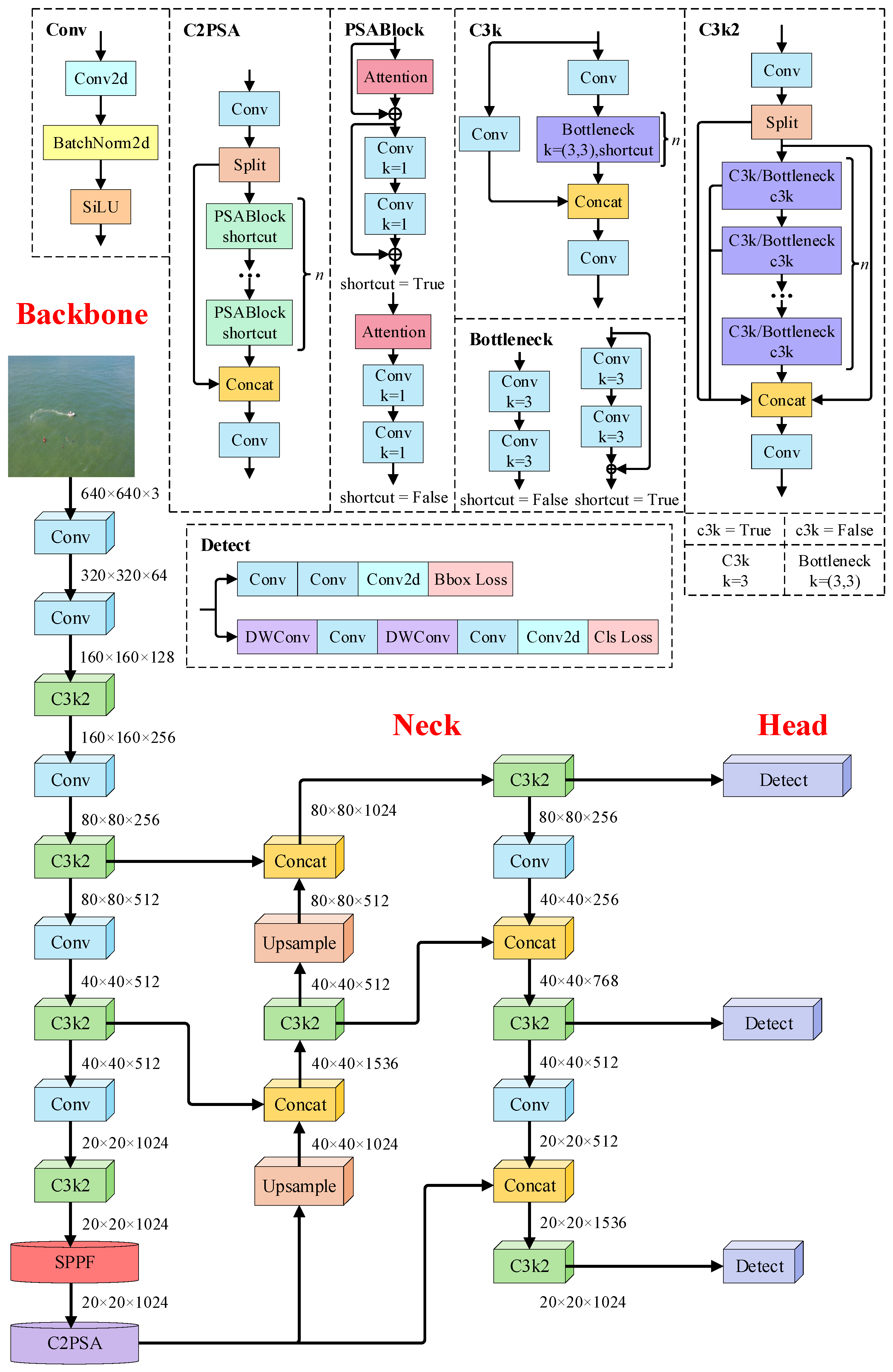

3.1. Overview of YOLO11

3.2. MFEF-YOLO

3.3. Dual-Branch Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast

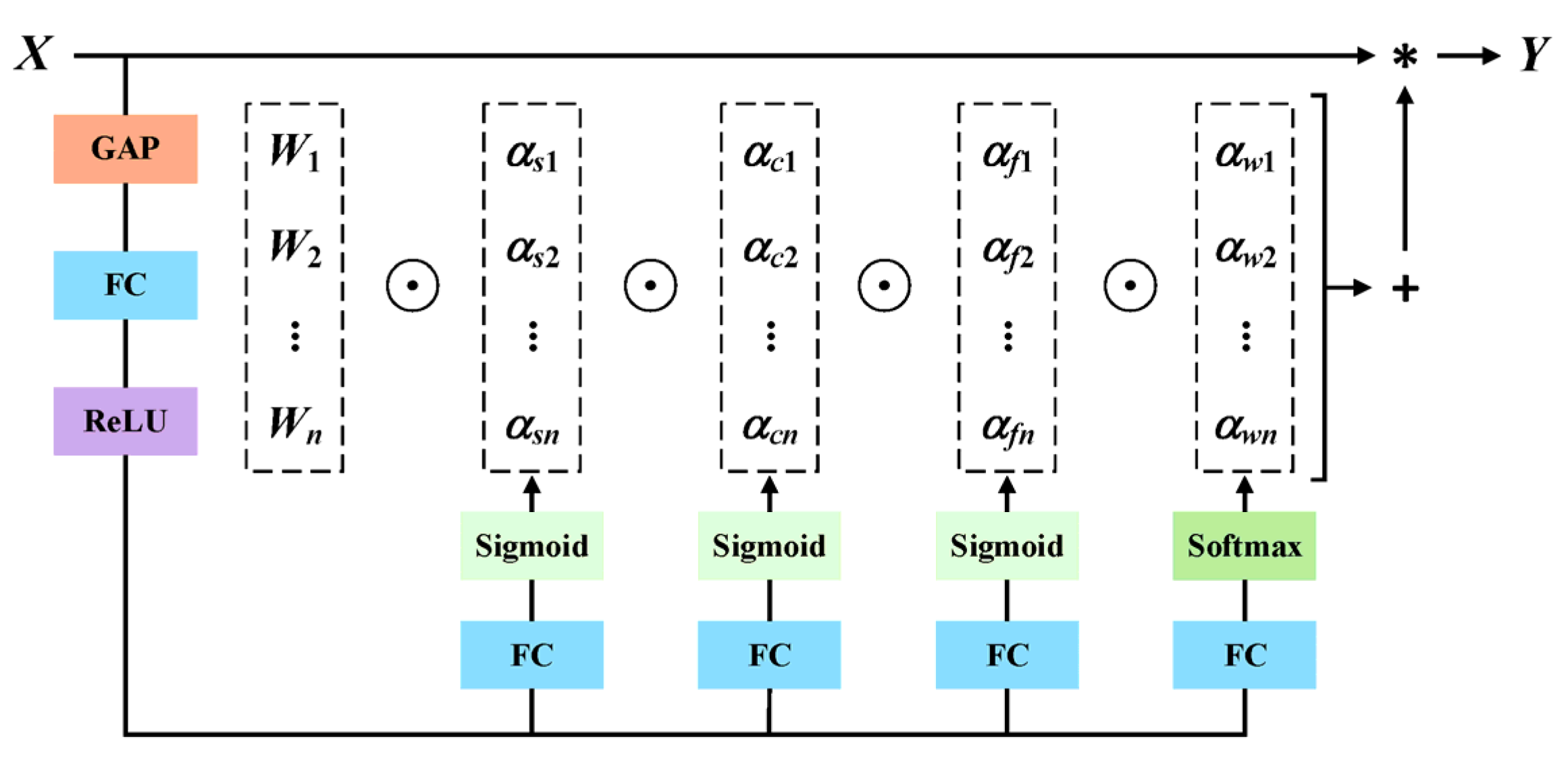

3.4. C3k2_ODConv

3.5. P2 Detection Head

3.6. Island-Based Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network

- (1)

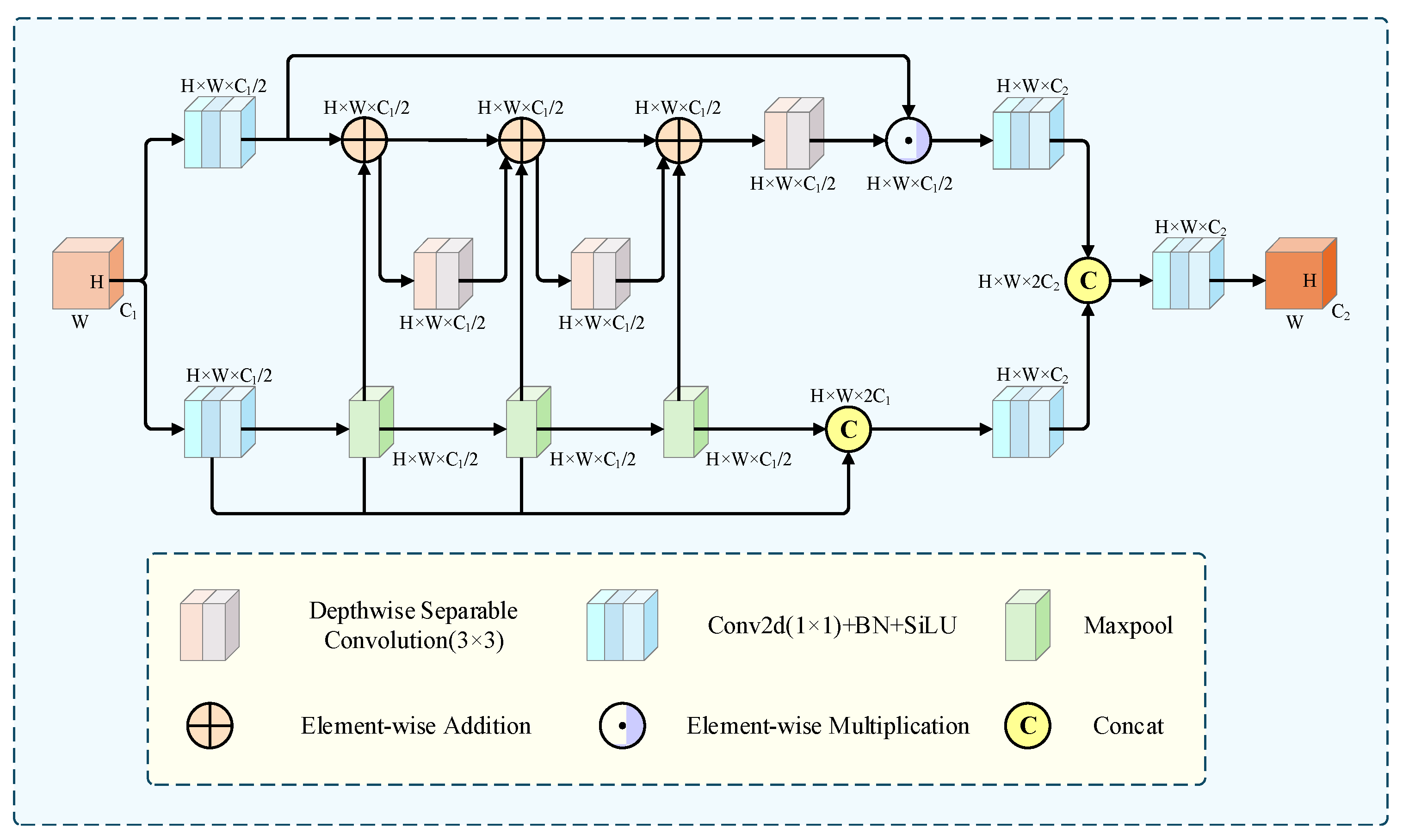

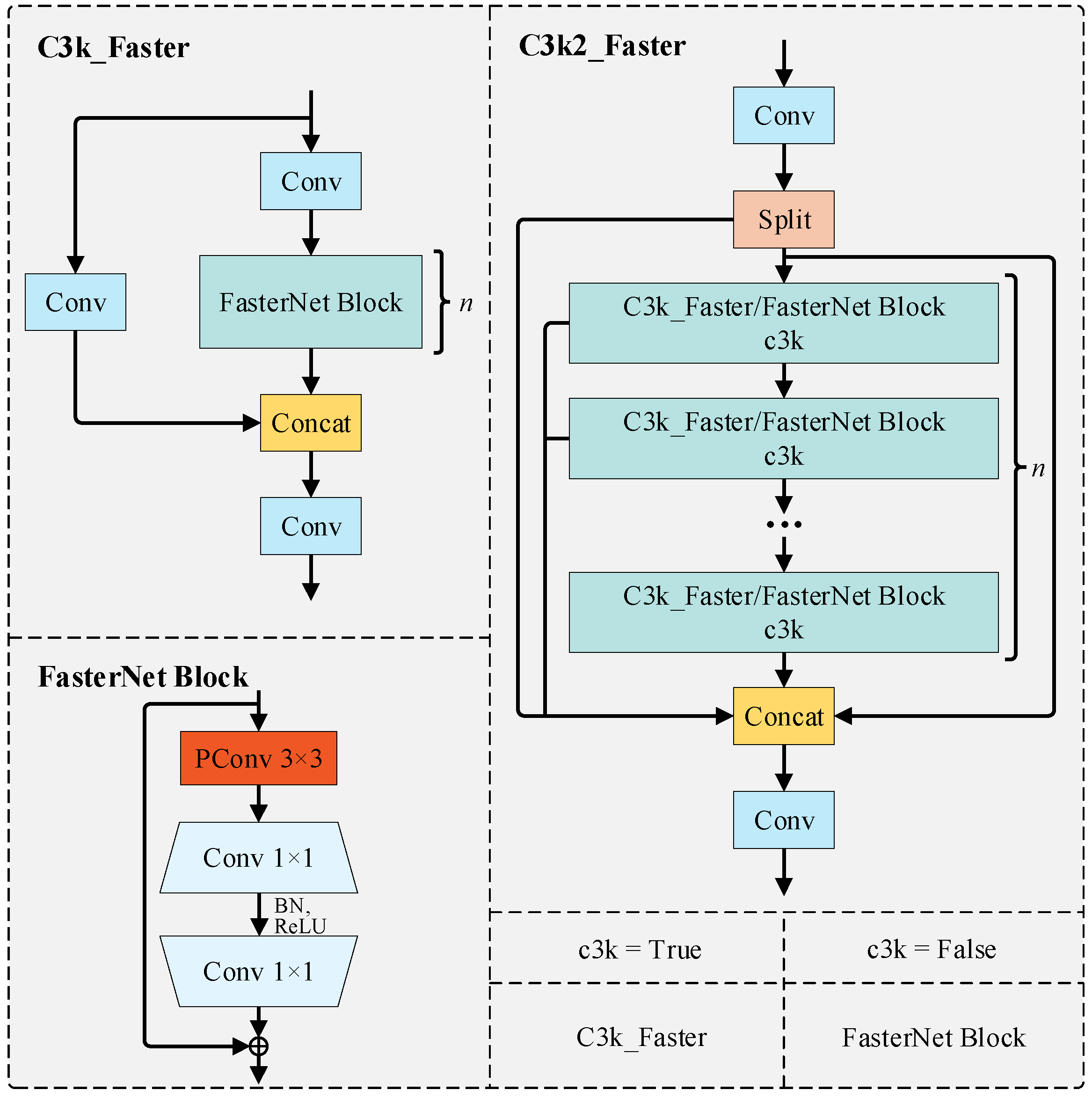

- C3k2_Faster: To enhance detection speed and reduce model complexity, we incorporate the FasterNet Block into the C3k2 module. The FasterNet Block originates from FasterNet [42], where researchers introduced partial convolution (PConv) that selectively performs standard convolution on specific input channels while preserving others to exploit feature map redundancy. Notably, PConv achieves efficient feature extraction by minimizing redundant computations and memory access. The FasterNet Block architecture consists of one PConv followed by two 1 × 1 convolutions, characterized by its simple structure and reduced parameters. While YOLO11’s C3k2 module employs Bottleneck blocks for performance enhancement, this approach significantly increases parameters and computational overhead. We therefore propose replacing the Bottleneck blocks in C3k2 with FasterNet Blocks, creating the novel C3k2_Faster module (architecture shown in Figure 8). Compared to the original C3k2, our module enhances learning capacity while reducing computational redundancy and memory access, achieving superior computational efficiency. Subsequent ablation studies demonstrate that C3k2_Faster effectively reduces computational load while improving both detection speed and accuracy.

- (2)

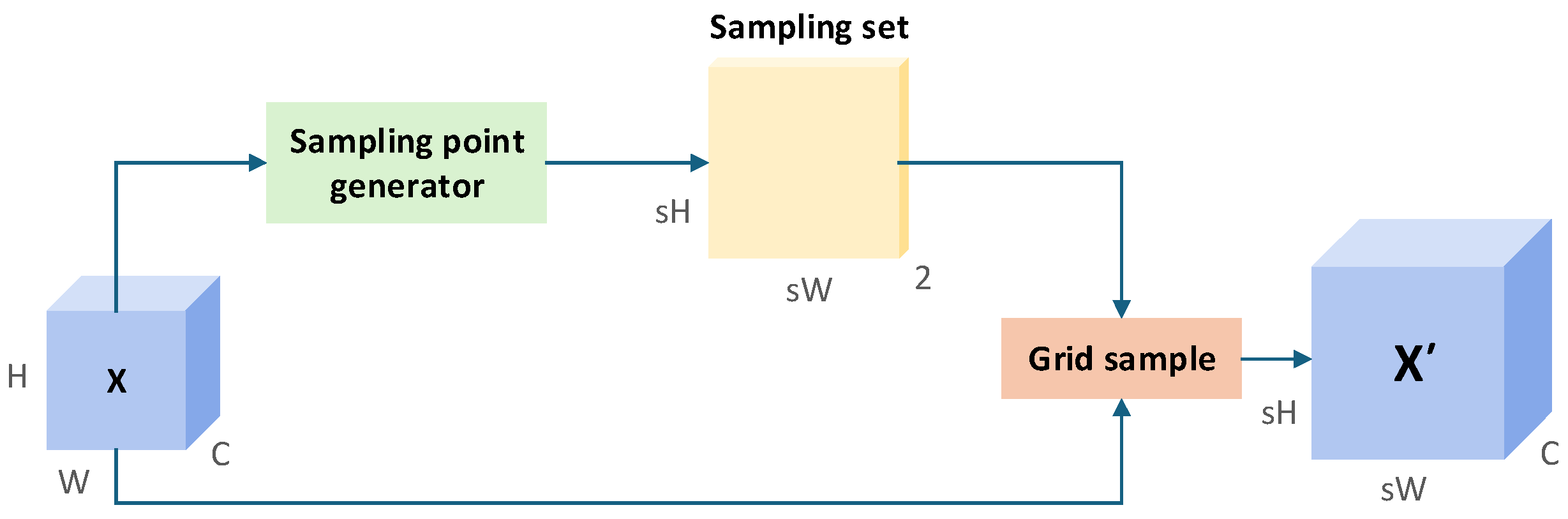

- DySample: In the YOLO11 architecture, the upsampling operation employs the nearest neighbor interpolation method. This approach amplifies the image by replicating the nearest pixel values, without considering the relationships between image content or features. As a result, it often leads to discontinuous pixel transitions, manifesting as jagged edges or blurred effects. Moreover, in drone-based aerial object detection scenarios, the targets in images are typically small, meaning each pixel’s information can significantly impact detection accuracy. To address this, we propose replacing the Upsample module in the neck network with DySample [43], a dynamic upsampling method based on point sampling, to enhance the upsampled features. The DySample module performs content-aware point sampling for upsampling, dynamically adjusting sampling locations according to the input features’ content. This enables DySample to better adapt to variations in image details and structures, thereby improving information retention in high-resolution feature maps and boosting object detection performance. Figure 9 illustrates the structure of the DySample module. The specific workflow is as follows: Given an input feature map of size and an upsampling scale factor s, a sampling point generator creates a sampling set of size . The grid_sample function then resamples X based on the sampling set, producing an upsampled feature map of size , thereby completing dynamic upsampling.

- (3)

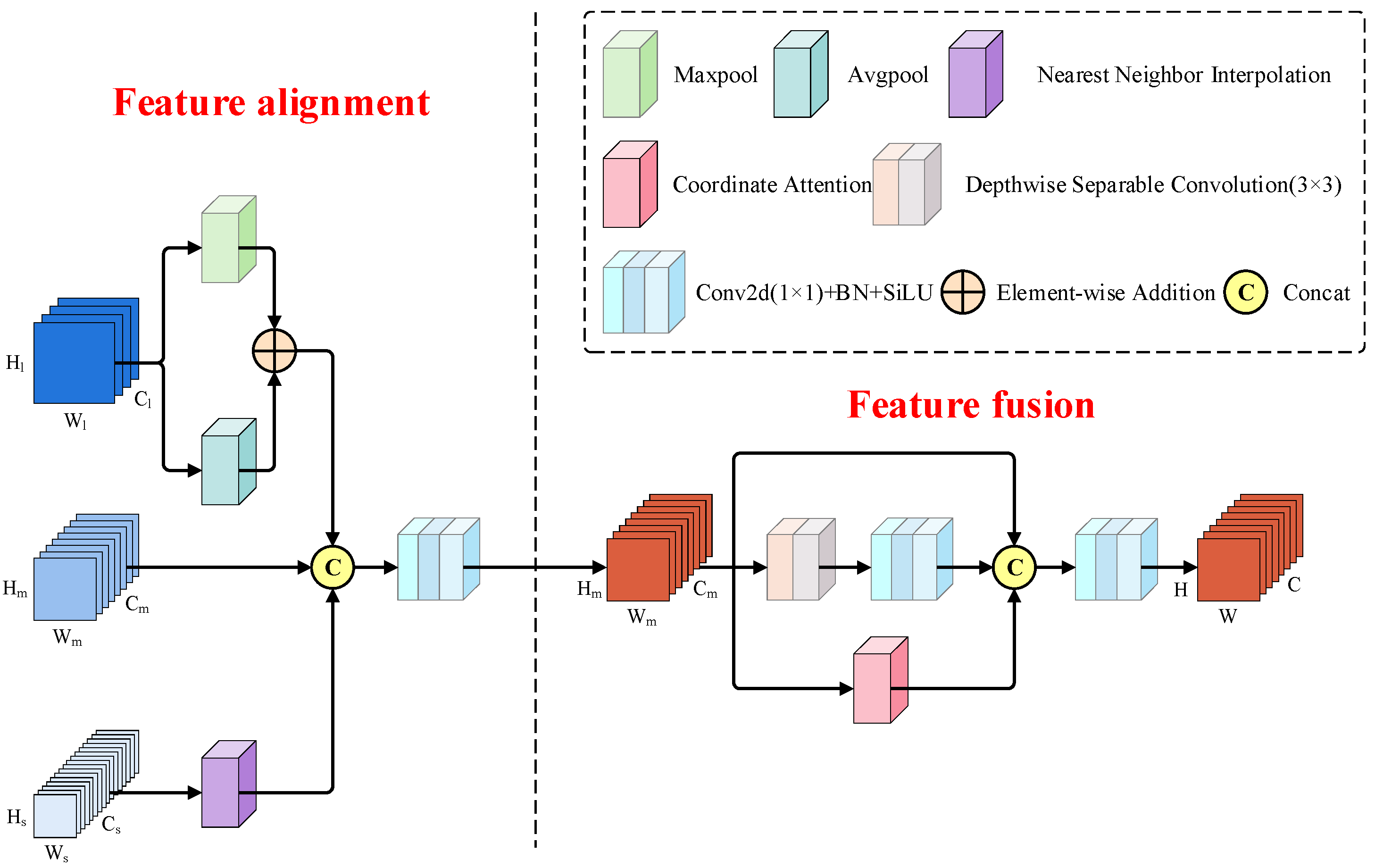

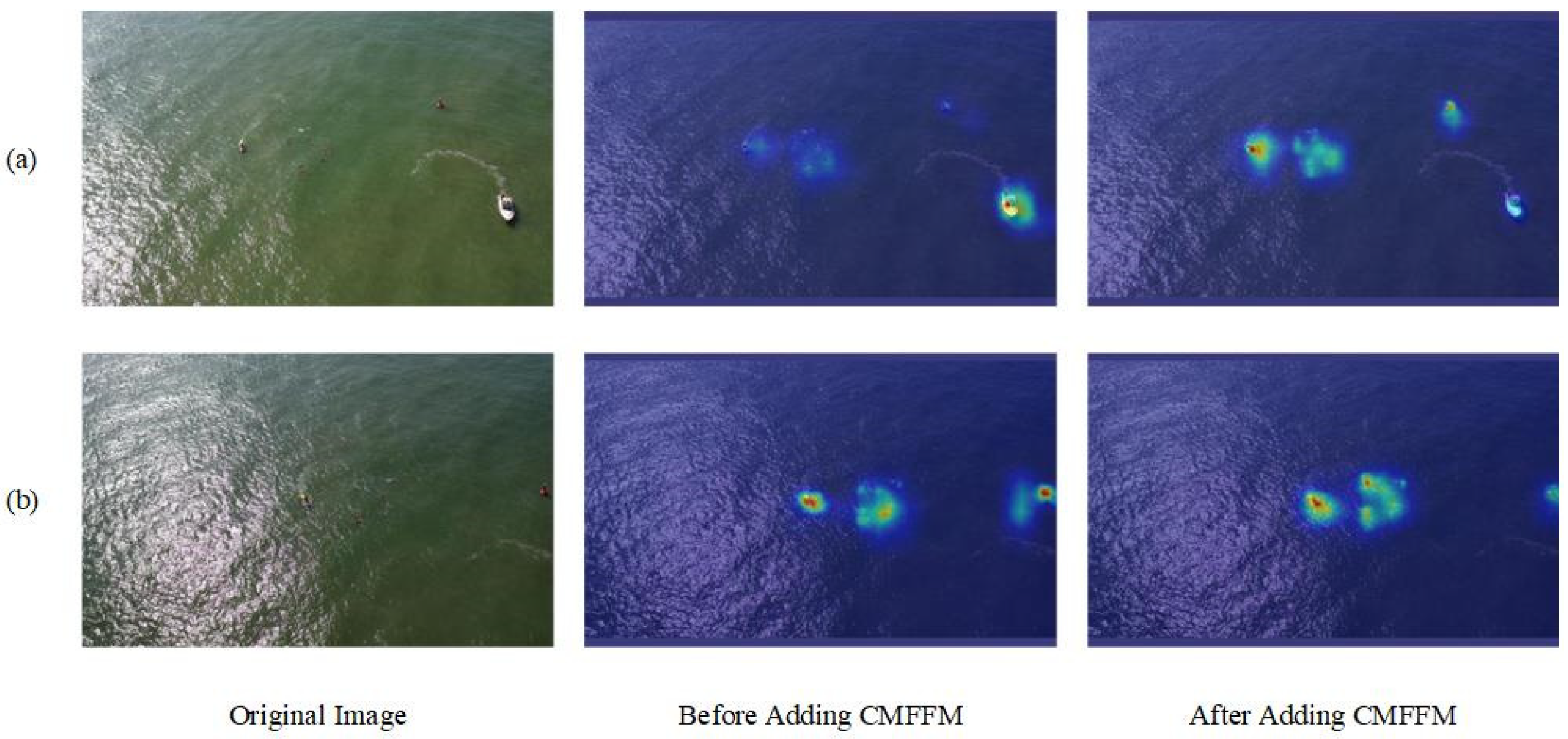

- Coordinate-guided Multi-scale Feature Fusion Module: In IMFFNet, to facilitate information exchange between spatial features of different scales and hierarchical semantics, we propose a Coordinate-guided Multi-scale Feature Fusion Module (CMFFM), as illustrated in Figure 10. The CMFFM consists of two components: feature alignment and feature fusion. For feature alignment, we align the dimensions of three input feature maps with varying scales. Considering that larger feature maps provide more low-level spatial details while smaller ones contain richer high-level semantic information, we choose to align them to the intermediate-scale feature map to balance both aspects. Specifically, we first downsample the large-scale feature map by a factor of 2 using a combination of average pooling and max pooling, yielding . Then, we upsample the small-scale feature map by a factor of 2 via nearest neighbor interpolation, producing . This ensures that both and are spatially aligned with the medium-scale feature map . Subsequently, , , and are concatenated along the channel dimension, followed by a convolution to adjust the channel dimension to match , thereby reducing computational complexity for subsequent operations. The mathematical formulation of the feature alignment process is as follows:

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

4.2. Dataset Description

- (1)

- SeaDronesSee: SeaDronesSee [44] is a large-scale benchmark dataset for maritime search-and-rescue object detection, designed to advance UAV-based search-and-rescue system development in marine environments. The dataset comprises 14,227 images captured by multiple cameras mounted on various UAVs, featuring varying altitudes, viewing angles, and time conditions. It contains critical maritime objects including vessels, swimmers, and rescue equipment, with resolutions up to 5456 × 3632 pixels. The annotations are categorized into six classes: ignore, swimmer, boat, jetski, life_saving_appliances, and buoy. The dataset is partitioned into training (8930 images), validation (1547 images), and test sets (3750 images).

- (2)

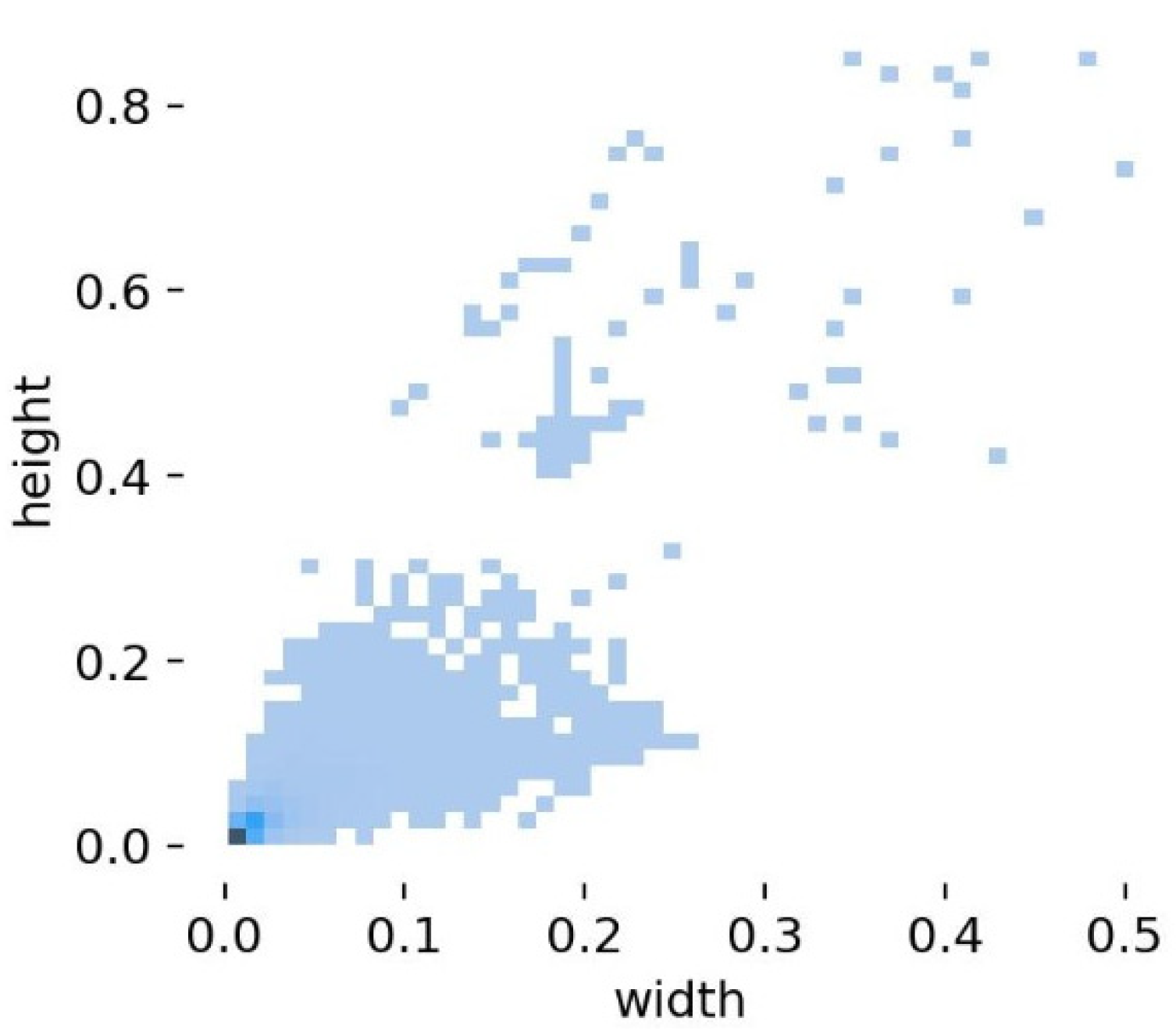

- TPDNV: To validate MFEF-YOLO’s detection capability for small and tiny objects, we constructed a specialized benchmark dataset named TPDNV. This dataset is curated from three established datasets: TinyPerson [45], DIOR [46], and NWPU VHR-10 [47,48,49]. We specifically selected sea_person and earth_person categories from TinyPerson, along with ship category from both DIOR and NWPU VHR-10, forming three unified classes in TPDNV: sea_person, earth_person, and ship. Through rigorous filtering, we excluded all larger targets from the original selections. The refined dataset was further augmented via downscaling, rotation, flipping, and cropping operations, resulting in 2368 images containing 120,822 annotated instances. The final dataset is partitioned into training (1664 images), validation (232 images), and test sets (472 images).

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Ablation Experiments

- (1)

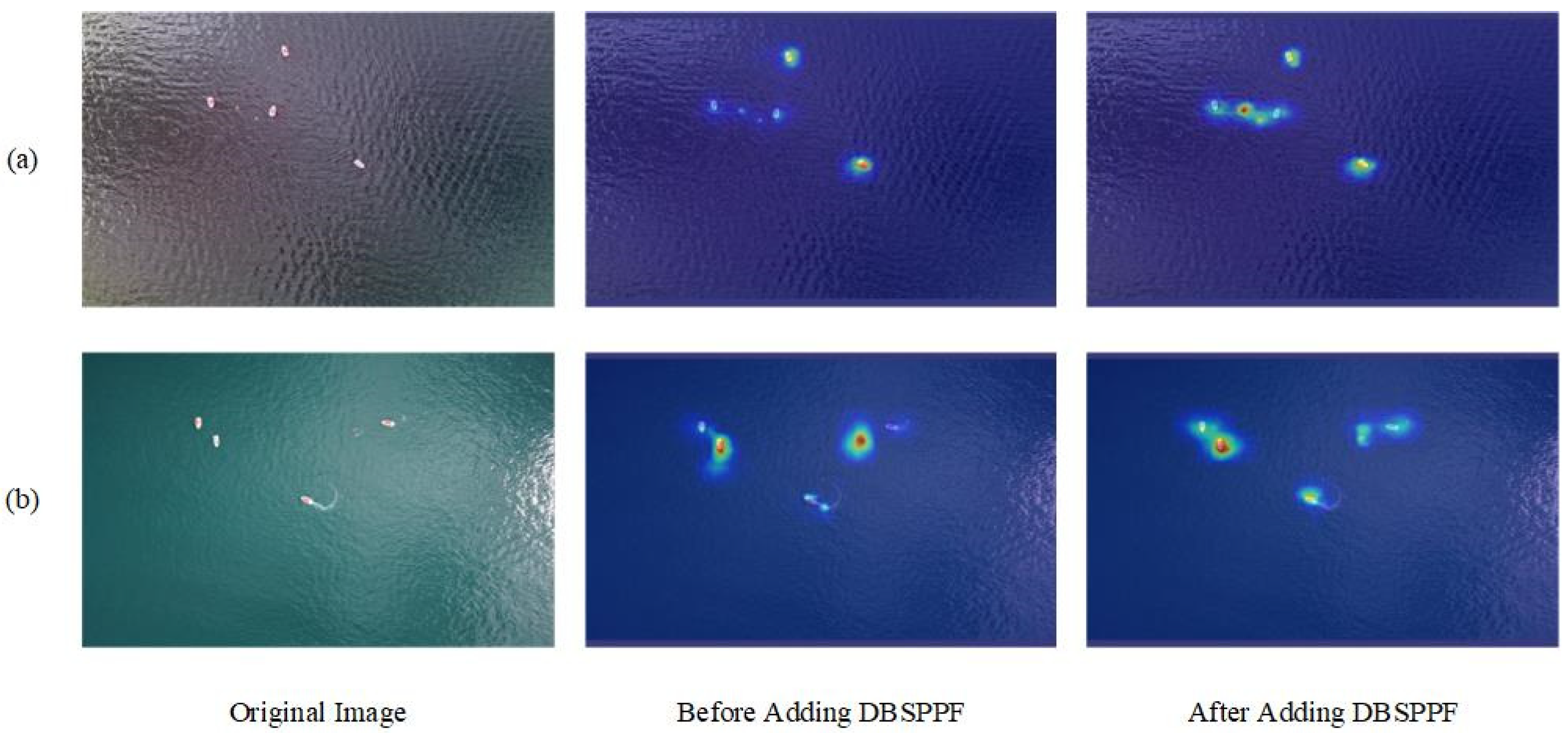

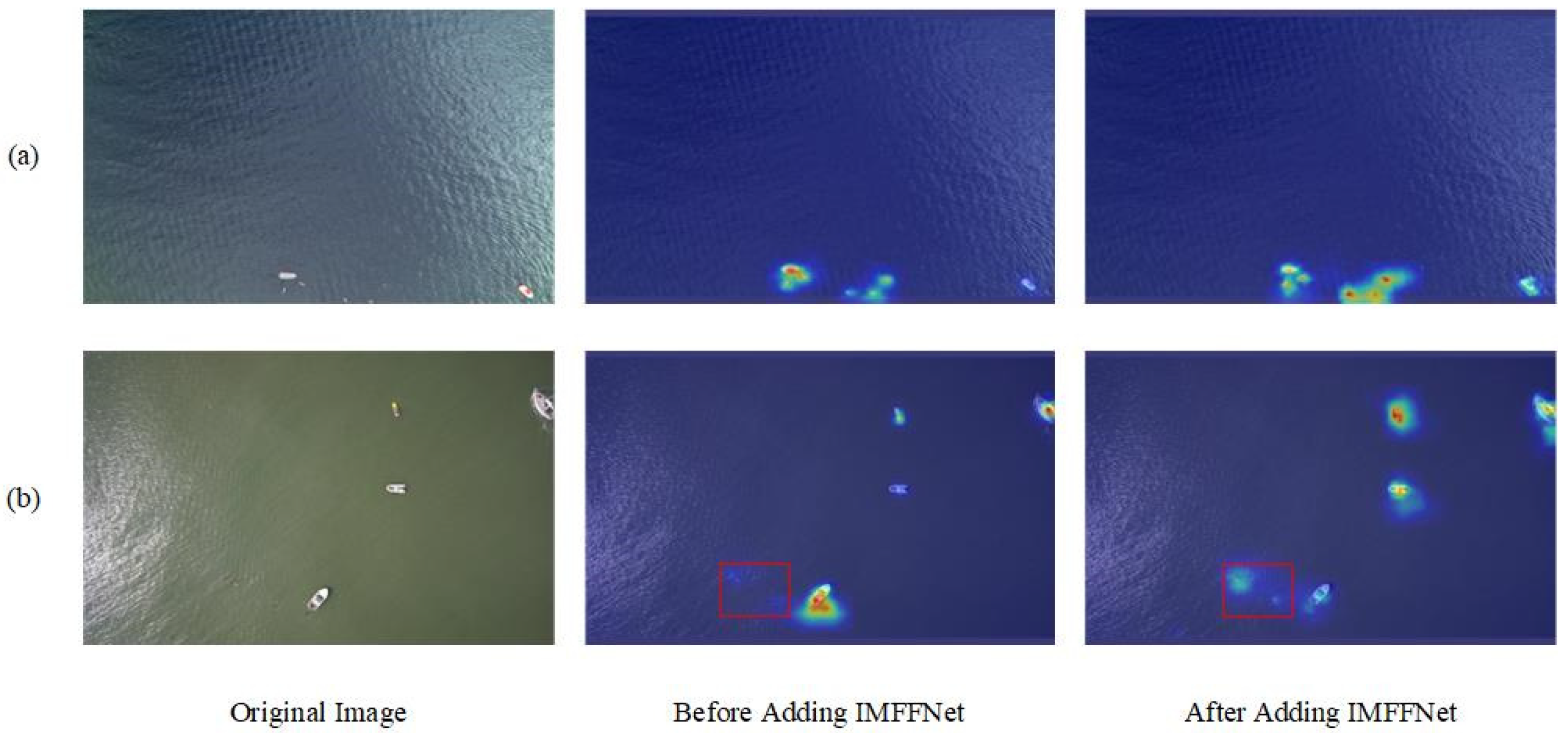

- DBSPPF: As indicated for module A in Table 3, replacing SPPF with DBSPPF in YOLO11n improves R, mAP50, mAP50:95, and mAPS despite a slight decrease in P. Notably, R and mAP50 increase by 0.023 and 0.014, respectively. The mAPS improvement indicates that DBSPPF’s dual-branch structure enhances small object detection. Additionally, DBSPPF improves FPS, demonstrating its efficiency in accelerating inference. Figure 11 visualizes feature extraction before and after DBSPPF integration, where brighter red regions indicate higher model attention. The results show more concentrated and distinct hotspots around target areas with DBSPPF, confirming its effectiveness in improving localization accuracy and focus.

- (2)

- C3k2_ODConv: As detailed in Table 3 (A + B approach), replacing C3k2 with C3k2_ODConv in the backbone of YOLO11n improves P, mAP50, and mAP50:95 by 0.015, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively. The incorporation of ODConv not only enhances the feature extraction capability of C3k2 but also reduces the computational cost of the model, decreasing from 6.5 G to 6.1 G.

- (3)

- P2 Detection Head: In this section, we first compare and analyze different detection head combinations before conducting comparisons with other modules. The neck of YOLO11 contains three detection layers corresponding to P3, P4, and P5 heads. We evaluated three distinct head configurations, with the results presented in Table 4. Comparing the P2, P3, P4, P5 set with the P3, P4, P5 set in the table, the incorporation of the P2 detection head significantly enhances overall model accuracy, improving R by 0.054, mAP50 by 0.044, mAP50:95 by 0.004, and mAPS by 0.084. This improvement stems from the resolution characteristics: the feature map at the P3 head has dimensions of pixels ( downsampled relative to the input image), where small targets (objects smaller than pixels in the COCO dataset) would occupy less than pixels, leading to feature loss during detection. In contrast, the P2 head’s feature map provides higher spatial resolution, preserving richer positional and detailed information that facilitates small object localization and boosts detection accuracy.

- (4)

- IMFFNet: In this section, we first conduct ablation studies on the components within the Island-based Multi-scale Feature Fusion Network (IMFFNet), followed by comparative analysis with other modules. The IMFFNet architecture primarily consists of three key components: C3k2_Faster, DySample, and CMFFM. Building upon the experimental configuration A + B + C from Table 3, we systematically evaluate these modules through ablation experiments, with results presented in Table 5. The symbol ‘✓’ beneath each module name in the table indicates its activation status in the corresponding experiment.

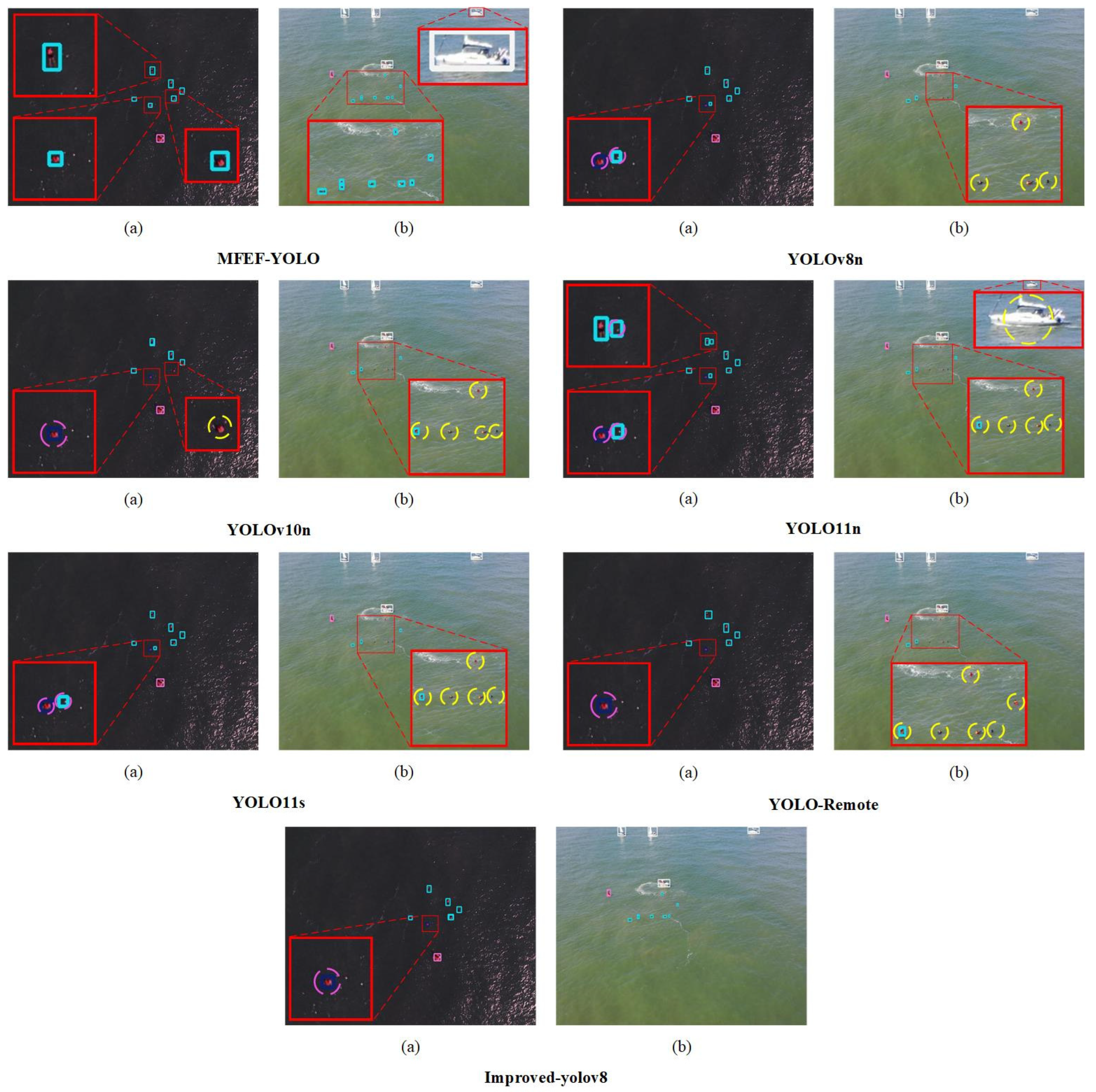

4.5. Comparative Experiments

- (1)

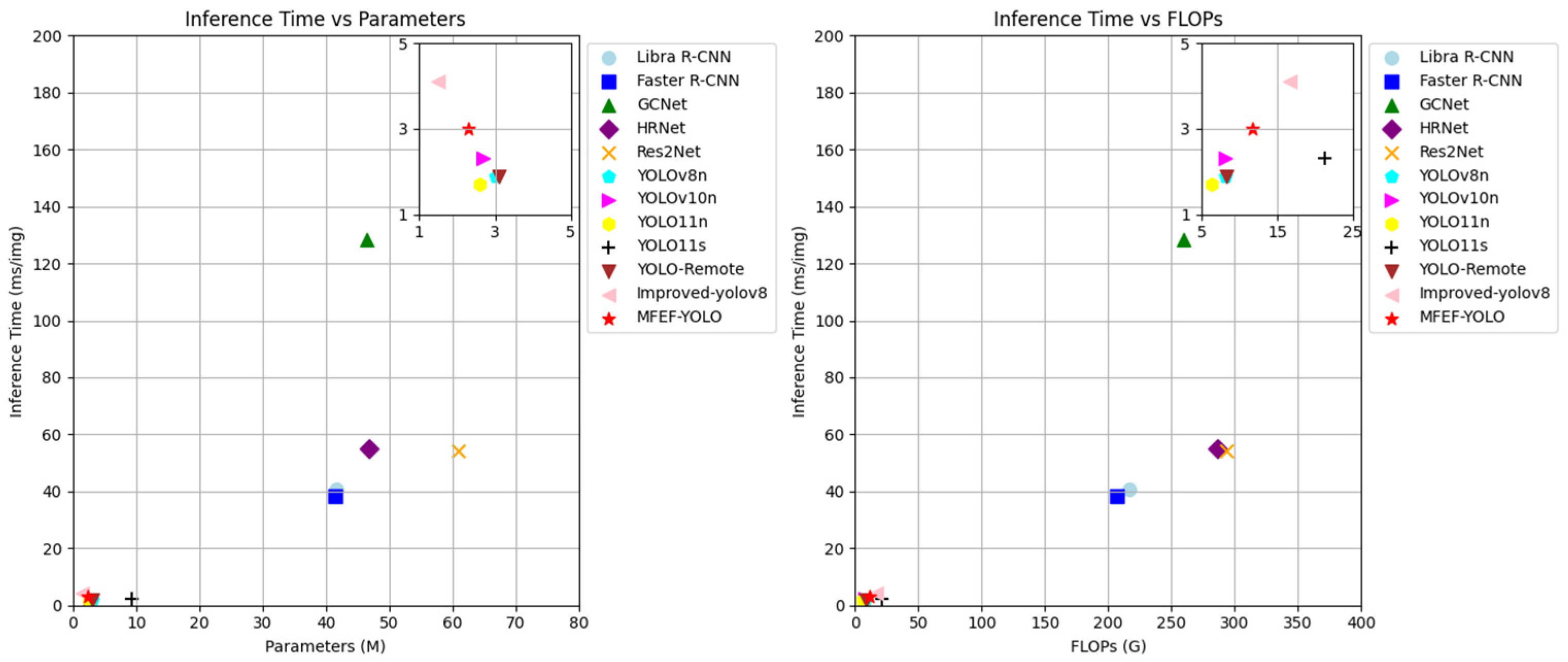

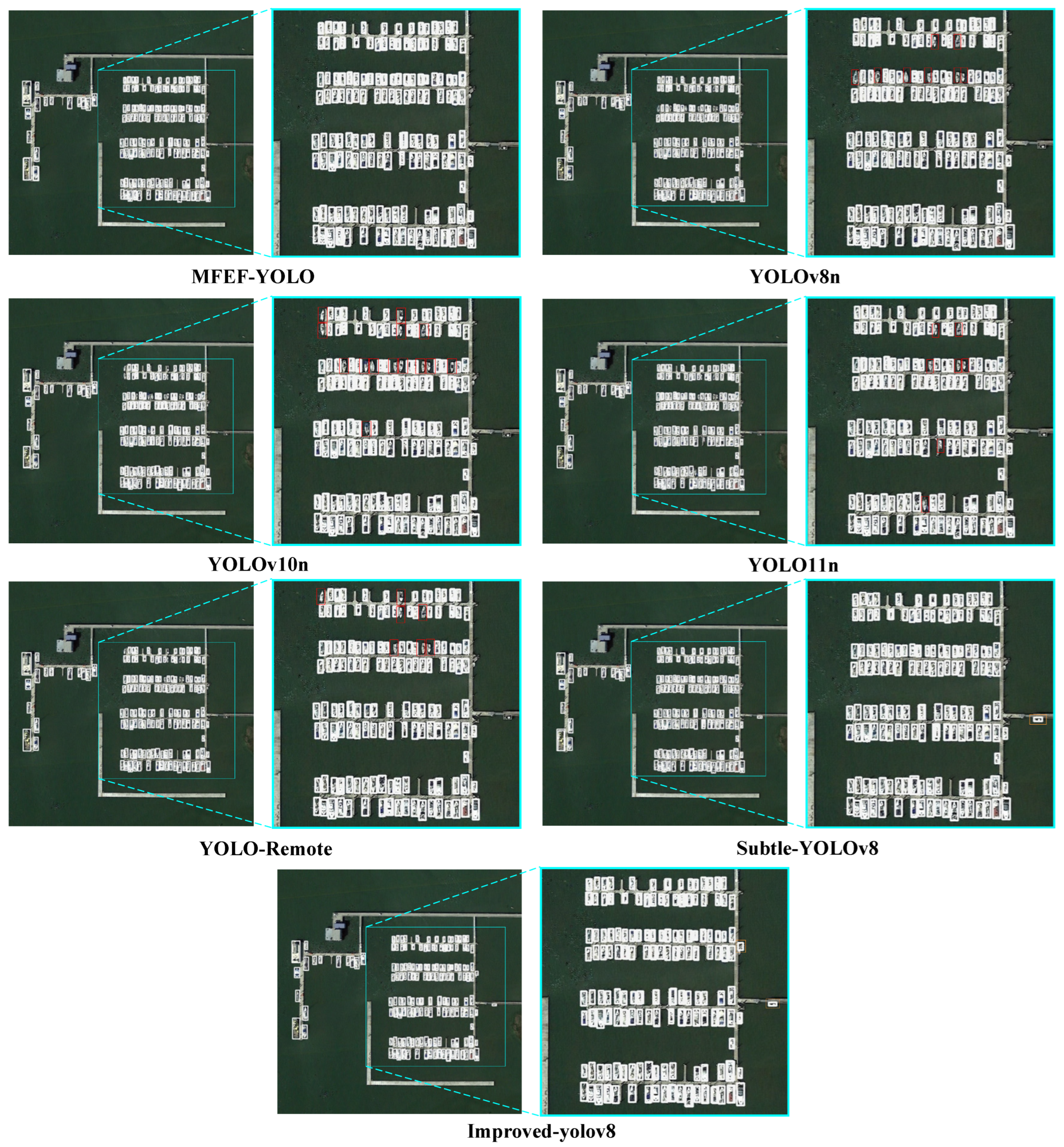

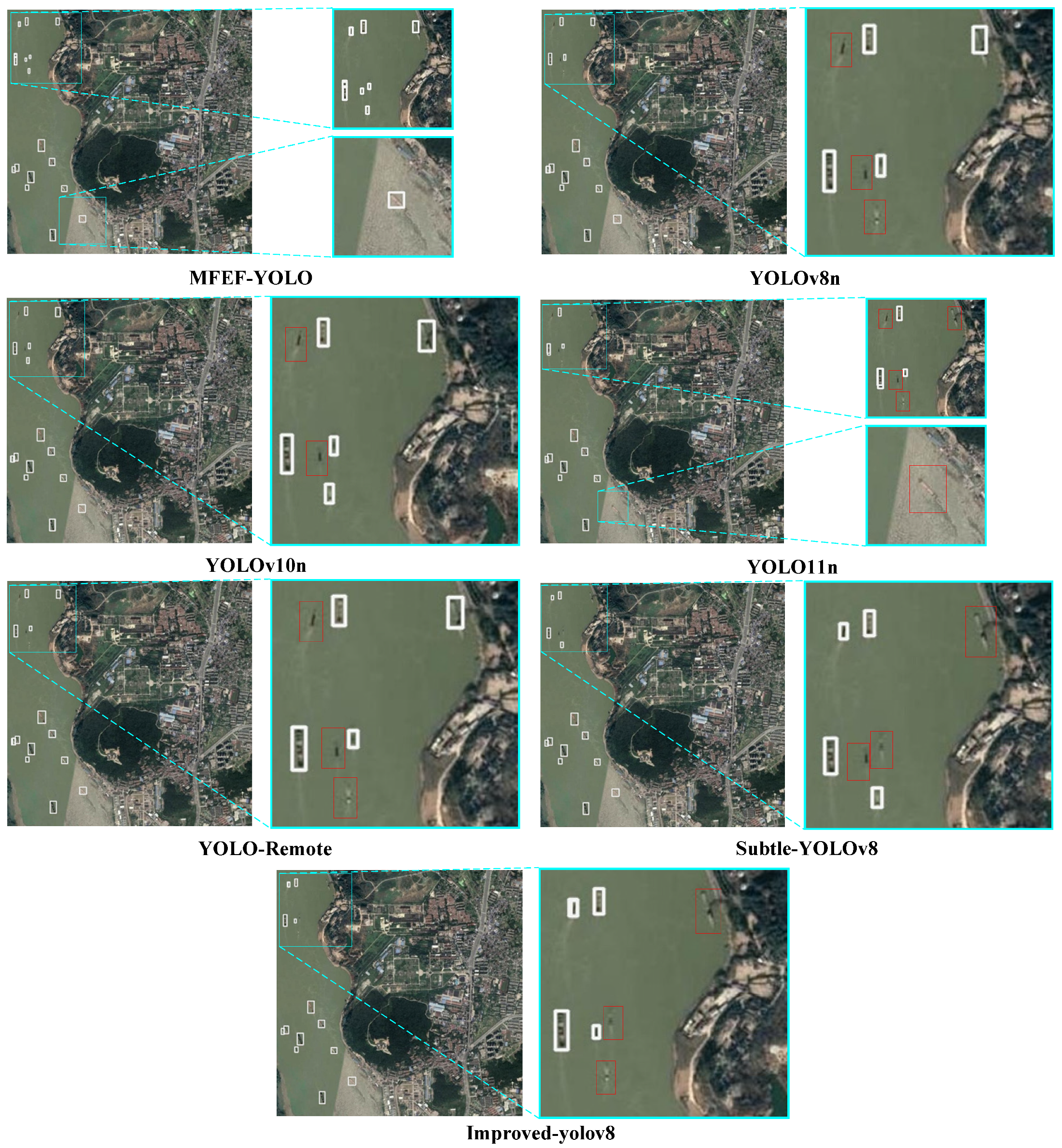

- SeaDronesSee: As demonstrated in Table 6, MFEF-YOLO achieves state-of-the-art detection accuracy when compared with 11 competing models. With comparable parameter counts, MFEF-YOLO exhibits superior performance in mAP50:95, surpassing YOLOv8n, YOLOv10n, YOLO11n, YOLO-Remote, and Improved-yolov8 by 0.043, 0.054, 0.042, 0.054, and 0.016, respectively. Remarkably, MFEF-YOLO outperforms YOLO11n with fewer parameters, demonstrating improvements of 0.11 in mAP50 and 0.042 in mAP50:95. Additionally, MFEF-YOLO maintains higher accuracy than YOLO11s while reducing both parameter size (by 4×) and computational cost (by 2×). The comprehensive results presented in Table 6 and Figure 14 reveal that MFEF-YOLO achieves an optimal balance between detection accuracy and inference efficiency. While maintaining high precision, its inference time remains competitive with YOLOv10n and YOLO11s, with only marginal increases of 1.1 ms and 1.3 ms compared to YOLOv8n and YOLO11n, respectively. These results collectively demonstrate that MFEF-YOLO establishes new benchmarks for small object detection in drone imagery applications.

- (2)

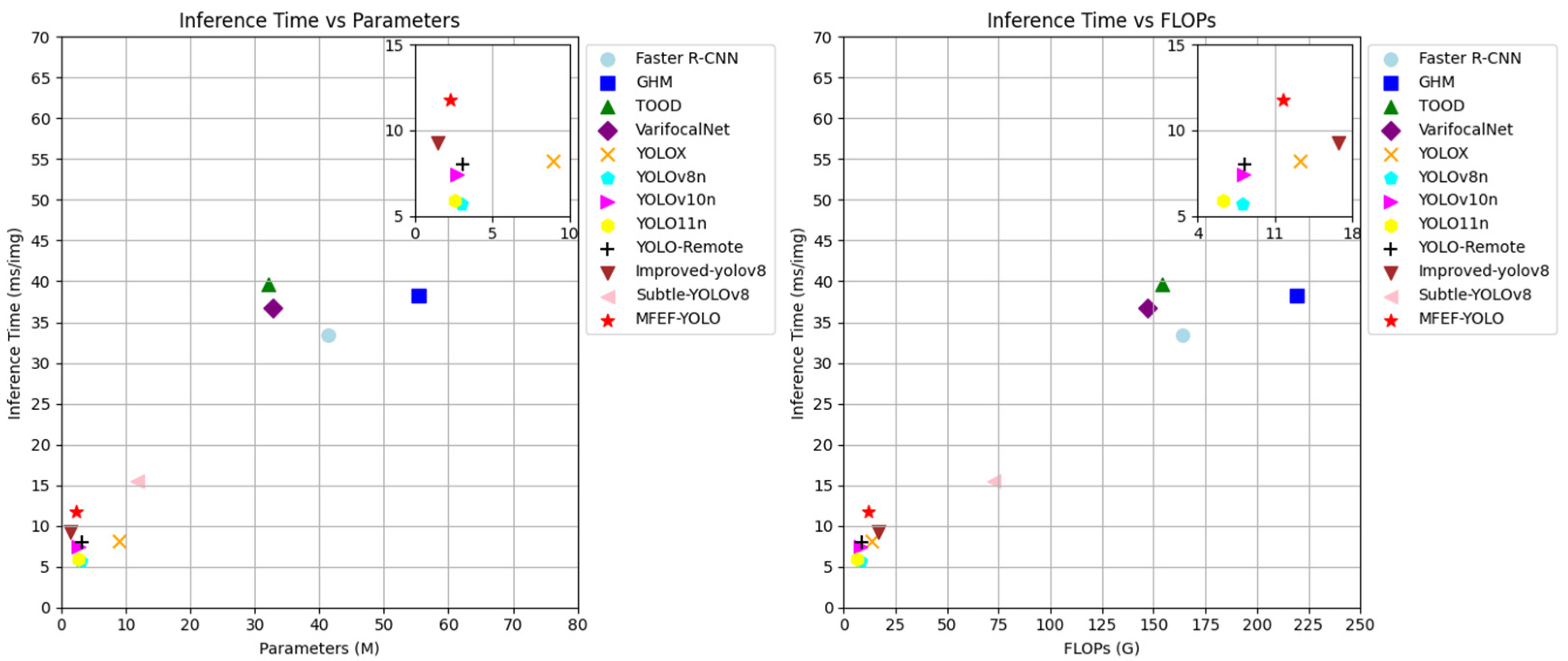

- TPDNV: Table 7 compares the detection performance of 12 different models, where MFEF-YOLO outperforms all others, achieving mAP50 and mAP50:95 scores of 0.474 and 0.228, respectively. Crucially, under identical training hyperparameters, MFEF-YOLO not only reduces the number of parameters but also improves detection accuracy compared to the baseline model. Moreover, while YOLOX, Subtle-YOLOv8, and MFEF-YOLO exhibit comparable mAP50 performance, MFEF-YOLO maintains a clear advantage in both parameter efficiency and computational cost—an essential feature for UAV applications with constrained storage and computing resources. As demonstrated in Figure 15, MFEF-YOLO achieves superior detection accuracy while keeping inference time highly competitive, differing by only 6.1 ms and 5.9 ms compared to YOLOv8n and YOLO11n, respectively.

4.6. Experimental Visualization and Analytical Evaluation

4.7. Comparative Analysis of Different SPPF Module and Neck Module Enhancement Approaches

- (1)

- Comparative Analysis of Enhanced SPPF Module Variants: To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed DBSPPF module, we conducted a comprehensive comparative study using YOLO11n as the baseline. In this experiment, we replaced the original SPPF module with five alternatives: DBSPPF, FocalModulation [61], SPPF-LSKA [33], Efficient-SPPF [32], and RFB [62], while keeping all other network components unchanged. As shown in Table 8, SPPF-LSKA achieved the highest P of 0.860, while Efficient-SPPF obtained the best R of 0.629. Notably, DBSPPF outperformed all counterparts in both mAP50 (0.675) and mAP50:95 (0.399) metrics. For small object detection (mAPS), RFB showed superior performance (0.235). Comprehensive analysis reveals that under comparable model parameters and computational costs, DBSPPF demonstrates the best overall performance, particularly excelling in the critical mAP50 and mAP50:95 metrics, demonstrating its dual advantages in both accuracy and efficiency.

- (2)

- Comparative Analysis of Enhanced Neck Network Architectures: To validate the effectiveness of our proposed IMFFNet, we conducted comprehensive comparative experiments with state-of-the-art neck network architectures. All experiments were performed via the YOLO11n framework using identical configurations (P2, P3, P4 detection heads) for fair comparison. As shown in Table 9, IMFFNet achieves superior performance across all key metrics: (1) leading in mAP50, mAP50:95, and mAPS; (2) ranking second in both P and R; while (3) maintaining relatively lower computational complexity and parameter count. The comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that IMFFNet strikes an optimal balance between detection accuracy and model efficiency, establishing its superior performance for UAV-based object detection tasks.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, T.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, R.; Cheng, N.; Feng, H. Maritime Search and Rescue Based on Group Mobile Computing for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Unmanned Surface Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 7700–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S. DFLM-YOLO: A Lightweight YOLO Model with Multiscale Feature Fusion Capabilities for Open Water Aerial Imagery. Drones 2024, 8, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yun, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, F. Detection algorithm for dense small objects in high altitude image. Digit. Signal Process. 2024, 146, 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ruan, C.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Fu, C. MSC-YOLO: Improved YOLOv7 Based on Multi-Scale Spatial Context for Small Object Detection in UAV-View. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 79, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Guo, L.; He, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z. DPH-YOLOv8: Improved YOLOv8 Based on Double Prediction Heads for the UAV Image Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5647715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C. GGT-YOLO: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm for Drone-Based Maritime Cruising. Drones 2022, 6, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; NIPS Foundation: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, D.; He, W.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z. ARF-YOLOv8: A novel real-time object detection model for UAV-captured images detection. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, D.; Song, T.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, X. YOLO-SSP: An object detection model based on pyramid spatial attention and improved downsampling strategy for remote sensing images. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 1467–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: Delving Into High Quality Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, P.; Yan, J. FFCA-YOLO for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6517–6525. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the 8th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nikouei, M.; Baroutian, B.; Nabavi, S.; Taraghi, F.; Aghaei, A.; Sajedi, A.; Moghaddam, M.E. Small object detection: A comprehensive survey on challenges, techniques and real-world applications. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 27, 200561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yuan, B.; Du, J.; Chen, B.; Xie, H.; Tian, J.; Yuan, Z. MFFSODNet: Multiscale Feature Fusion Small Object Detection Network for UAV Aerial Images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5015214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhu, S.; Tang, G.; Ke, C.; Wang, T. A Small-Object Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8s for UAV Image Scenarios. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. SPMF: A saliency-based pseudo-multimodality fusion model for data-scarce maritime targets detection. Ocean Eng. 2026, 343, 123023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; He, T.; Qiao, L.; Duan, J.; Shi, X.; Yan, B.; Guo, C. MES-YOLO: An efficient lightweight maritime search and rescue object detection algorithm with improved feature fusion pyramid network. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2025, 109, 104453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fan, X.; Jian, H.; Xu, C.; Bei, W.; Ge, Q.; Zhao, T. YoloOW: A Spatial Scale Adaptive Real-Time Object Detection Neural Network for Open Water Search and Rescue From UAV Aerial Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5623115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Sun, C.; Ding, B.; Zhu, Y. OWRT-DETR: A Novel Real-Time Transformer Network for Small-Object Detection in Open-Water Search and Rescue From UAV Aerial Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4205313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Zhang, Y. LiteFlex-YOLO:A lightweight small target detection network for maritime unmanned aerial vehicles. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2025, 111, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhou, Y.; Song, R.; Yu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Modular YOLOv8 optimization for real-time UAV maritime rescue object detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Song, L.; Yin, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhan, T.; Huang, W. MFFCI–YOLOv8: A Lightweight Remote Sensing Object Detection Network Based on Multiscale Features Fusion and Context Information. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 19743–19755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhong, G.; Chu, Y.; Le, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, J. YOLO-Remote: An Object Detection Algorithm for Remote Sensing Targets. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155654–155665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liang, G.; Hu, Y.; Xi, Y.; Ning, F.; He, Z. YOLO-RLDW: An Algorithm for Object Detection in Aerial Images Under Complex Backgrounds. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 128677–128693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.W.; Po, L.-M.; Rehman, Y.A.U. Large Separable Kernel Attention: Rethinking the Large Kernel Attention design in CNN. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Miao, X.; Zuo, C. TFDNet: A triple focus diffusion network for object detection in urban congestion with accurate multi-scale feature fusion and real-time capability. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wan, Y. ELA: Efficient Local Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 22, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 936–944. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Small Object Detection in Traffic Scenes Based on Attention Feature Fusion. Sensors 2021, 21, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Cui, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, C. Rich-scale feature fusion network for salient object detection. IET Image Process. 2023, 17, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, A.; Yao, A.J.A. Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.07947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.h.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to Upsample by Learning to Sample. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 6004–6014. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, L.A.; Kiefer, B.; Messmer, M.; Zell, A. SeaDronesSee: A Maritime Benchmark for Detecting Humans in Open Water. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 3686–3696. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, N.; Ye, Q.; Han, Z. Scale Match for Tiny Person Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Snowmass, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 1246–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Zhou, P.; Guo, L. Multi-class geospatial object detection and geographic image classification based on collection of part detectors. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 98, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J. A survey on object detection in optical remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 117, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhou, P.; Han, J. Learning Rotation-Invariant Convolutional Neural Networks for Object Detection in VHR Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 7405–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Chen, K.; Shi, J.; Feng, H.; Ouyang, W.; Lin, D. Libra R-CNN: Towards Balanced Learning for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 821–830. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, J.; Lin, S.; Wei, F.; Hu, H. GCNet: Non-Local Networks Meet Squeeze-Excitation Networks and Beyond. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 1971–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5686–5696. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.-H.; Cheng, M.-M.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Torr, P. Res2Net: A New Multi-Scale Backbone Architecture. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G.J.A. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (NeurIPS 2024), Proceedings of the 38th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; NIPS Foundation: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, T.; Wu, W.; Zhang, J. Small object detection based on YOLOv8 in UAV perspective. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2024, 27, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Gradient Harmonized Single-stage Detector. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2018, 33, 8577–8584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. TOOD: Task-aligned One-stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3490–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Dayoub, F.; Sünderhauf, N. VarifocalNet: An IoU-aware Dense Object Detector. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8510–8519. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.J.A. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO Series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; Ma, L. Subtle-YOLOv8: A detection algorithm for tiny and complex targets in UAV aerial imagery. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 8949–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Jia, Y.S.; Zeng, W.X.; Wei, P. CDF-YOLOv8: City Recognition System Based on Improved YOLOv8. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 143745–143753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Li, C. SLR-YOLO: An improved YOLOv8 network for real-time sign language recognition. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 46, 1663–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.-M. DEA-Net: Single Image Dehazing Based on Detail-Enhanced Convolution and Content-Guided Attention. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 33, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Geng, Q.; Wan, M.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Z. Context and Spatial Feature Calibration for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 5465–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: A lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, W.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, R.; Du, X. Detection Technique Tailored for Small Targets on Water Surfaces in Unmanned Vessel Scenarios. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Device | Version |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows 10 |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 |

| CPU | Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-13490F |

| Python | 3.8 |

| PyTorch | 2.4.1 |

| CUDA | 12.4 |

| Parameter | Setup |

|---|---|

| Epochs | 200 |

| Patience | 0 |

| Batch size | 8 |

| Image size | 640 × 640 |

| Workers | 8 |

| Optimizer | SGD |

| Amp | False |

| Initial learning rate | 0.01 |

| Final learning rate | 0.0001 |

| Momentum | 0.937 |

| Algorithms | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAPS | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11n | 0.842 | 0.605 | 0.661 | 0.393 | 0.226 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 364.28 |

| A | 0.814 | 0.628 | 0.675 | 0.399 | 0.229 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 367.56 |

| A + B | 0.829 | 0.625 | 0.685 | 0.400 | 0.216 | 2.8 | 6.1 | 336.43 |

| A + B + C | 0.831 | 0.687 | 0.735 | 0.410 | 0.287 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 301.62 |

| A + B + C + D (Our) | 0.836 | 0.718 | 0.771 | 0.435 | 0.317 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 256.73 |

| Detection Head | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAPS | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3, P4, P5 | 0.829 | 0.625 | 0.685 | 0.400 | 0.216 | 2.8 | 6.1 | 336.43 |

| P2, P3, P4, P5 | 0.808 | 0.679 | 0.729 | 0.404 | 0.300 | 2.9 | 9.9 | 295.02 |

| P2, P3, P4 | 0.831 | 0.687 | 0.735 | 0.410 | 0.287 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 301.62 |

| C3k2_Faster | DySample | CMFFM | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAPS | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.831 | 0.687 | 0.735 | 0.410 | 0.287 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 301.62 | |||

| ✓ | 0.848 | 0.694 | 0.746 | 0.422 | 0.301 | 2.1 | 9.2 | 304.75 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.810 | 0.720 | 0.763 | 0.422 | 0.286 | 2.1 | 9.2 | 294.59 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.836 | 0.718 | 0.771 | 0.435 | 0.317 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 256.73 |

| Methods | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Params (M) | FLOPS (G) | Inference Time (ms/img) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Libra R-CNN [50] | 0.572 | 0.373 | 41.6 | 217.0 | 40.7 | 23.8 |

| Faster R-CNN [12] | 0.567 | 0.361 | 41.4 | 207.0 | 38.5 | 25.1 |

| GCNet [51] | 0.595 | 0.383 | 46.5 | 260.0 | 128.2 | 15.5 |

| HRNet [52] | 0.571 | 0.369 | 46.9 | 286.0 | 55.2 | 17.8 |

| Res2Net [53] | 0.587 | 0.370 | 61.0 | 294.0 | 54.1 | 18.2 |

| YOLOv8n | 0.663 | 0.392 | 3.0 | 8.1 | 1.9 | 333.3 |

| YOLOv10n [54] | 0.643 | 0.381 | 2.7 | 8.2 | 2.3 | 384.6 |

| YOLO11n | 0.661 | 0.393 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 364.3 |

| YOLO11s | 0.699 | 0.429 | 9.4 | 21.3 | 2.3 | 331.6 |

| YOLO-Remote [32] | 0.642 | 0.381 | 3.1 | 8.3 | 1.9 | 344.8 |

| Improved-yolov8 [55] | 0.740 | 0.419 | 1.5 | 16.7 | 4.1 | 196.1 |

| MFEF-YOLO | 0.771 | 0.435 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 3.0 | 256.7 |

| Methods | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Params (M) | FLOPS (G) | Inference Time (ms/img) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN | 0.283 | 0.137 | 41.4 | 164.0 | 33.4 | 29.1 |

| GHM [56] | 0.261 | 0.118 | 55.4 | 219.0 | 38.2 | 25.6 |

| TOOD [57] | 0.374 | 0.180 | 32.0 | 154.0 | 39.7 | 24.9 |

| VarifocalNet [58] | 0.357 | 0.168 | 32.7 | 147.0 | 36.8 | 26.6 |

| YOLOX [59] | 0.473 | 0.172 | 8.9 | 13.3 | 8.2 | 104.3 |

| YOLOv8n | 0.448 | 0.223 | 3.0 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 98.0 |

| YOLOv10n | 0.428 | 0.216 | 2.7 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 114.9 |

| YOLO11n | 0.444 | 0.225 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 114.4 |

| YOLO-Remote | 0.435 | 0.218 | 3.1 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 106.4 |

| Improved-yolov8 | 0.466 | 0.217 | 1.5 | 16.7 | 9.3 | 64.5 |

| Subtle-YOLOv8 [60] | 0.472 | 0.216 | 11.8 | 72.8 | 15.5 | 55.2 |

| MFEF-YOLO | 0.474 | 0.228 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 11.8 | 72.7 |

| Method | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAPS | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11n + DBSPPF | 0.814 | 0.628 | 0.675 | 0.399 | 0.229 | 2.8 | 6.5 |

| YOLO11n + FocalModulation | 0.787 | 0.625 | 0.658 | 0.395 | 0.216 | 2.7 | 6.4 |

| YOLO11n + SPPF-LSKA | 0.860 | 0.614 | 0.661 | 0.398 | 0.228 | 2.9 | 6.5 |

| YOLO11n + Efficient-SPPF | 0.776 | 0.629 | 0.653 | 0.391 | 0.222 | 2.6 | 6.4 |

| YOLO11n + RFB | 0.791 | 0.615 | 0.659 | 0.394 | 0.235 | 2.7 | 6.5 |

| Method | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | mAPS | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11n + IMFFNet | 0.837 | 0.707 | 0.761 | 0.432 | 0.321 | 2.1 | 11.9 |

| YOLO11n + CGAFusion [63] | 0.835 | 0.698 | 0.745 | 0.423 | 0.301 | 2.2 | 14.3 |

| YOLO11n + CSFCN [64] | 0.824 | 0.712 | 0.749 | 0.427 | 0.309 | 2.0 | 10.8 |

| YOLO11n + slimneck [65] | 0.814 | 0.692 | 0.723 | 0.404 | 0.291 | 2.0 | 9.2 |

| YOLO11n + [66] | 0.861 | 0.702 | 0.742 | 0.424 | 0.319 | 4.4 | 29.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhang, P.; Geng, T.; Yuan, X.; Ji, B.; Zhu, S.; Ma, R. MFEF-YOLO: A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in Aerial Imagery over Open Water. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243996

Liu Q, Yu H, Zhang P, Geng T, Yuan X, Ji B, Zhu S, Ma R. MFEF-YOLO: A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in Aerial Imagery over Open Water. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243996

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qi, Haiyang Yu, Ping Zhang, Tingting Geng, Xinru Yuan, Bingqian Ji, Shengmin Zhu, and Ruopu Ma. 2025. "MFEF-YOLO: A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in Aerial Imagery over Open Water" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243996

APA StyleLiu, Q., Yu, H., Zhang, P., Geng, T., Yuan, X., Ji, B., Zhu, S., & Ma, R. (2025). MFEF-YOLO: A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in Aerial Imagery over Open Water. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243996