Mapping Four Decades of Treeline Ecotone Migration: Remote Sensing of Alpine Ecotone Shifts on the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains

Highlights

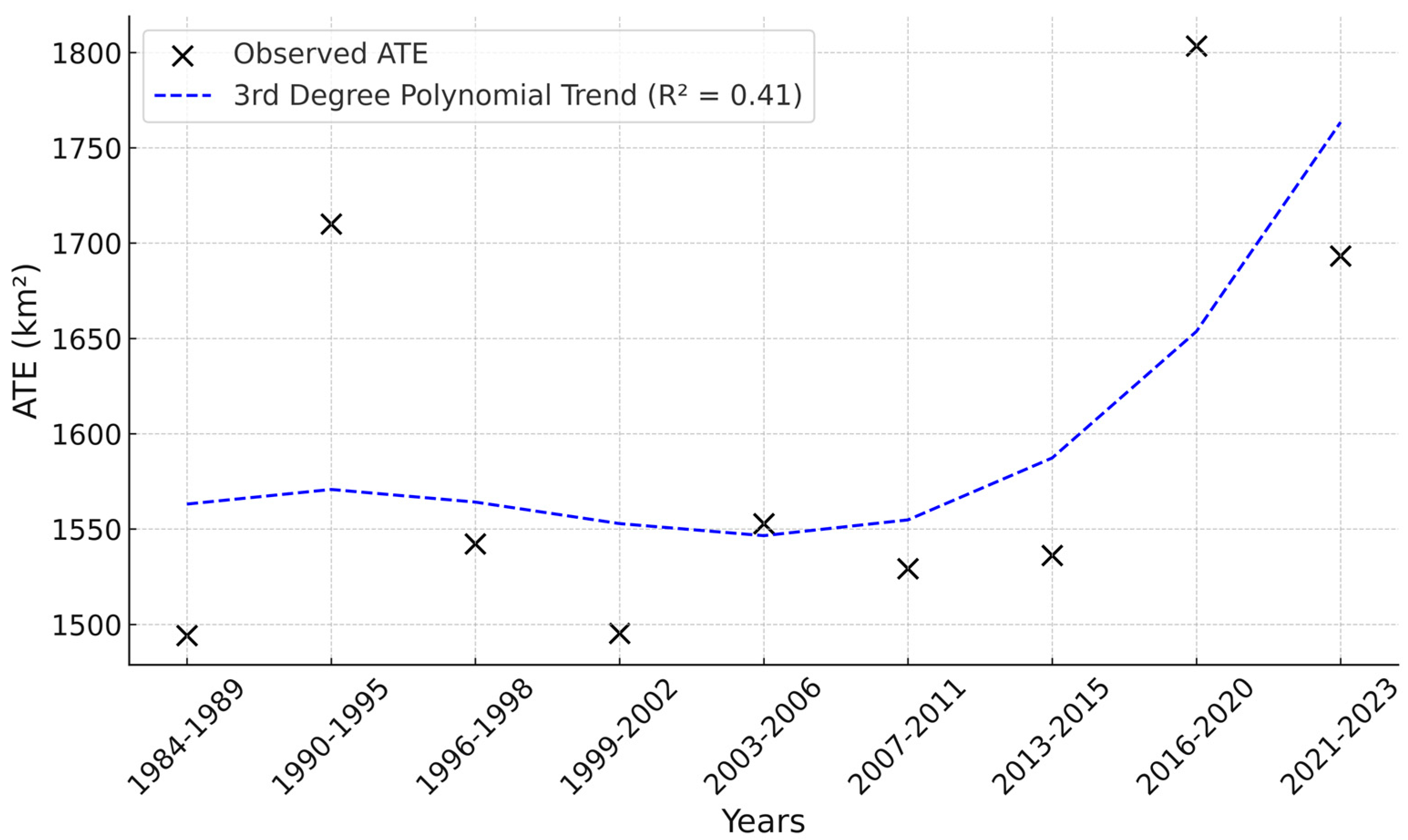

- Over the past four decades (1984–2023), the Alpine Treeline Ecotone (ATE) has increased by 13.32% (~199 km2), with substantial increases in the Bow and Athabasca watersheds, as well as significant gains in the northern aspects of the Eastern Slope of the Canadian Rocky Mountains (ESCR).

- The study developed and implemented the Alpine Treeline Ecotone Index (ATEI) using Landsat imagery and Google Earth Engine (GEE), a novel spatial method that combines NDVI gradients, elevation, and logistic regression to detect and monitor changes to ATE.

- The responses of ATE migration to climate change vary across aspects and watersheds and are shaped by microclimate, disturbances, and topographic conditions, while the ATEI remains a reliable remote-sensing tool for long-term vegetation monitoring in fragile alpine ecosystems.

- The upward expansion of ATE zones may affect regional hydrology and watershed dynamics, altering snowmelt timing, runoff patterns, and downstream water availability.

- For ecological forecasting and biodiversity conservation, understanding spatial shifts in treeline zones is essential, particularly in sensitive alpine habitats.

- This research can contribute to the development of evidence-based policies, environmental monitoring, and adaptive land management strategies in mountainous regions affected by climate change.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

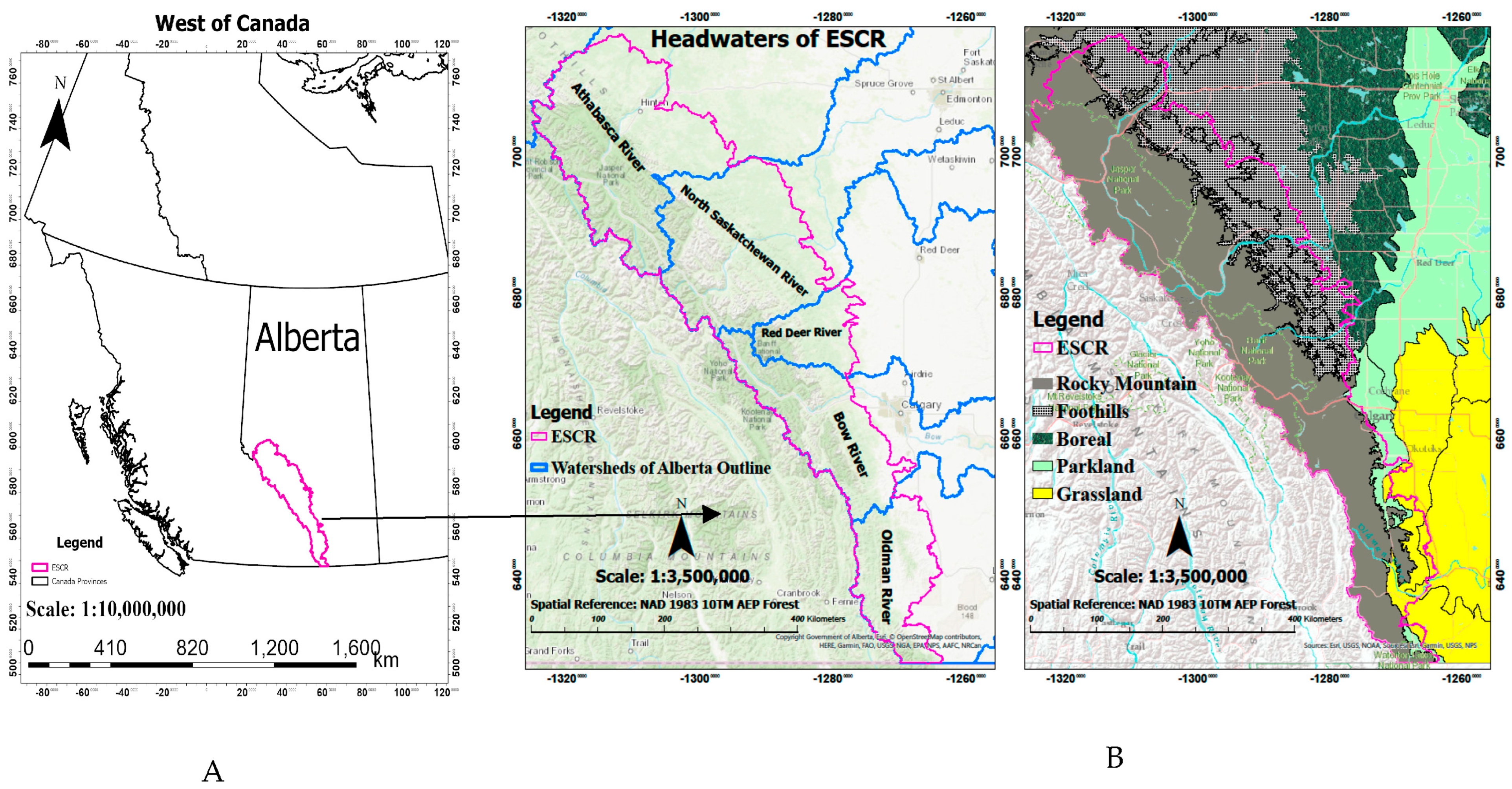

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Landsat Satellite Imagery

2.2.2. Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)

2.2.3. High-Resolution Reference Imagery

2.3. Methods

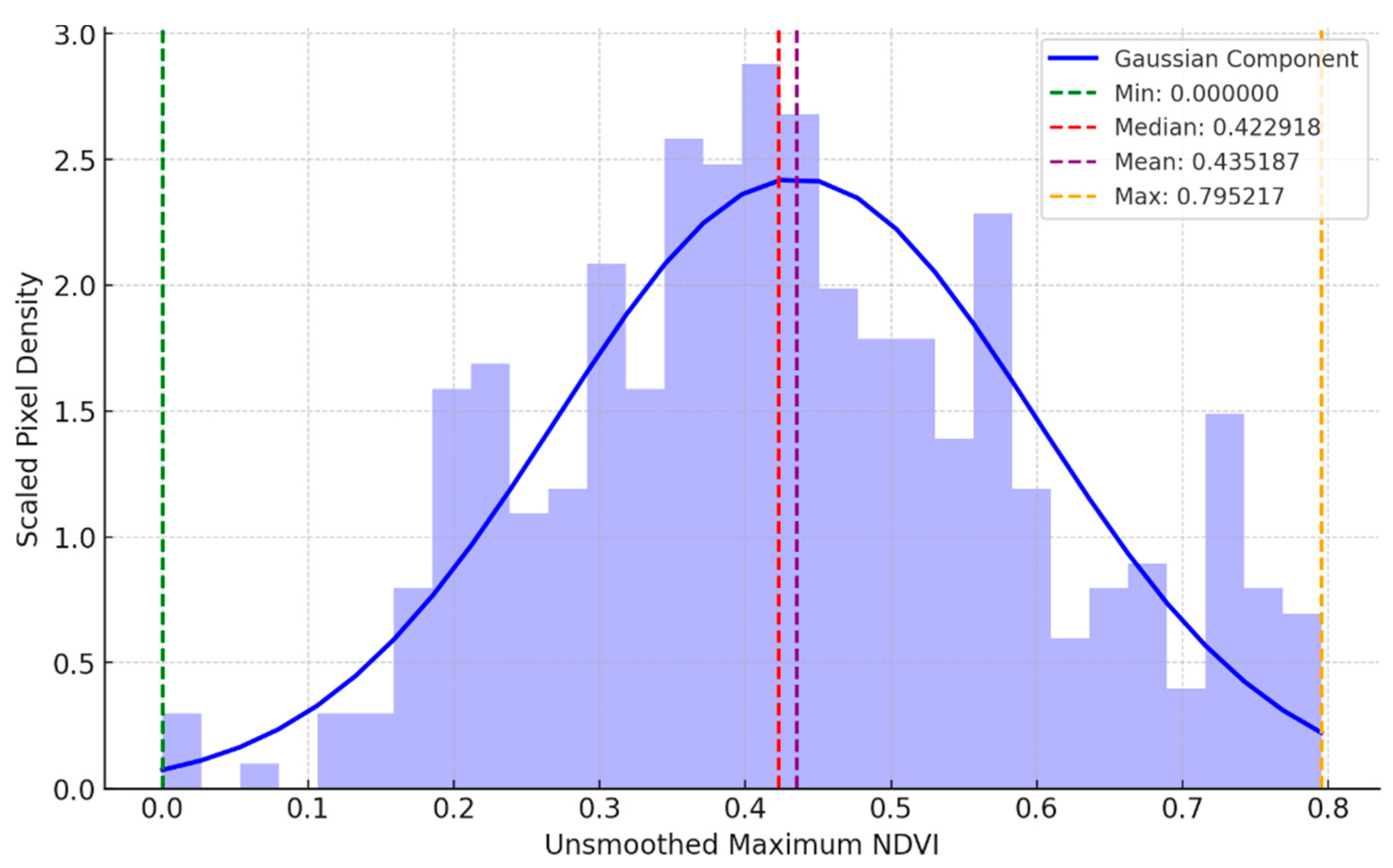

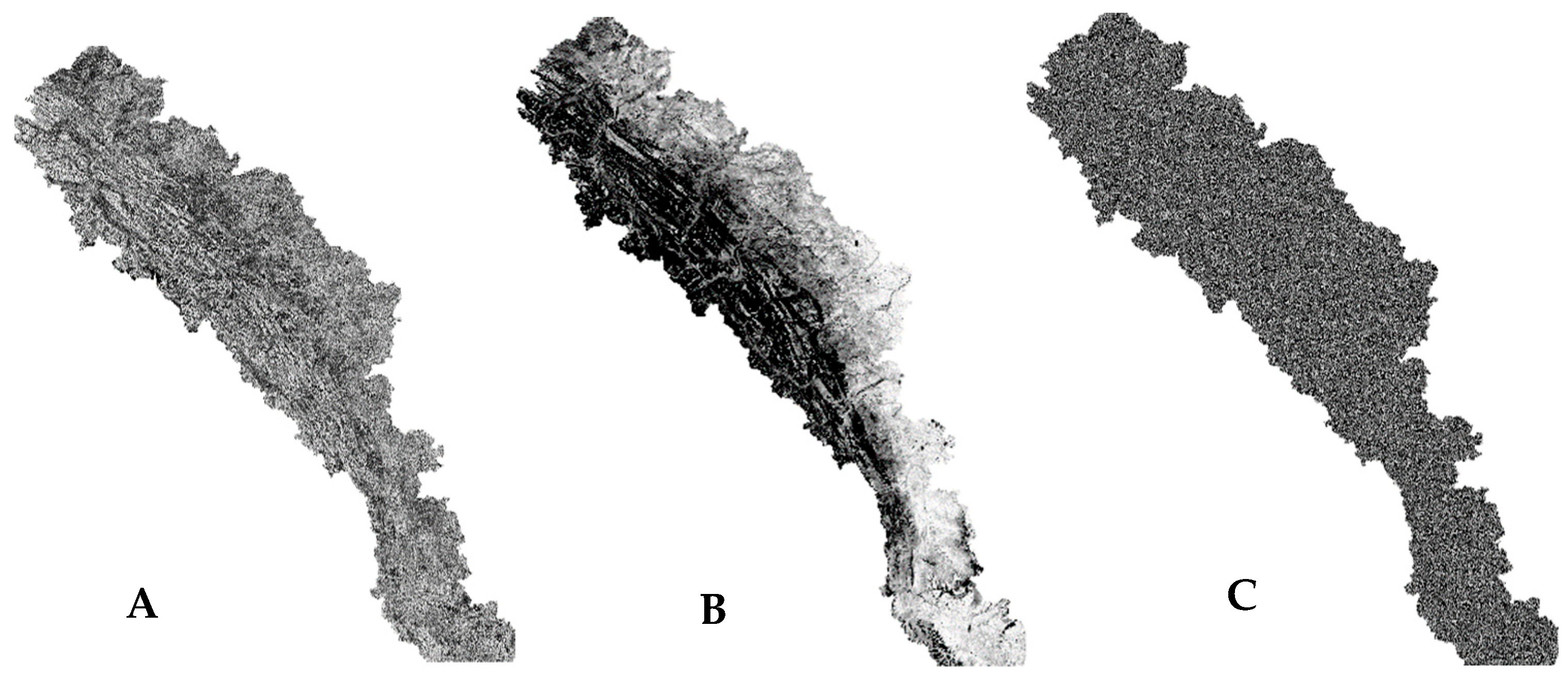

2.3.1. Max NDVI

2.3.2. Vegetation Indices and Ecotone Delineation

2.3.3. Alpine Treeline Ecotone Index (ATEI)

2.3.4. Watershed-Level Aggregation

2.3.5. Validation and Accuracy Assessment

3. Results

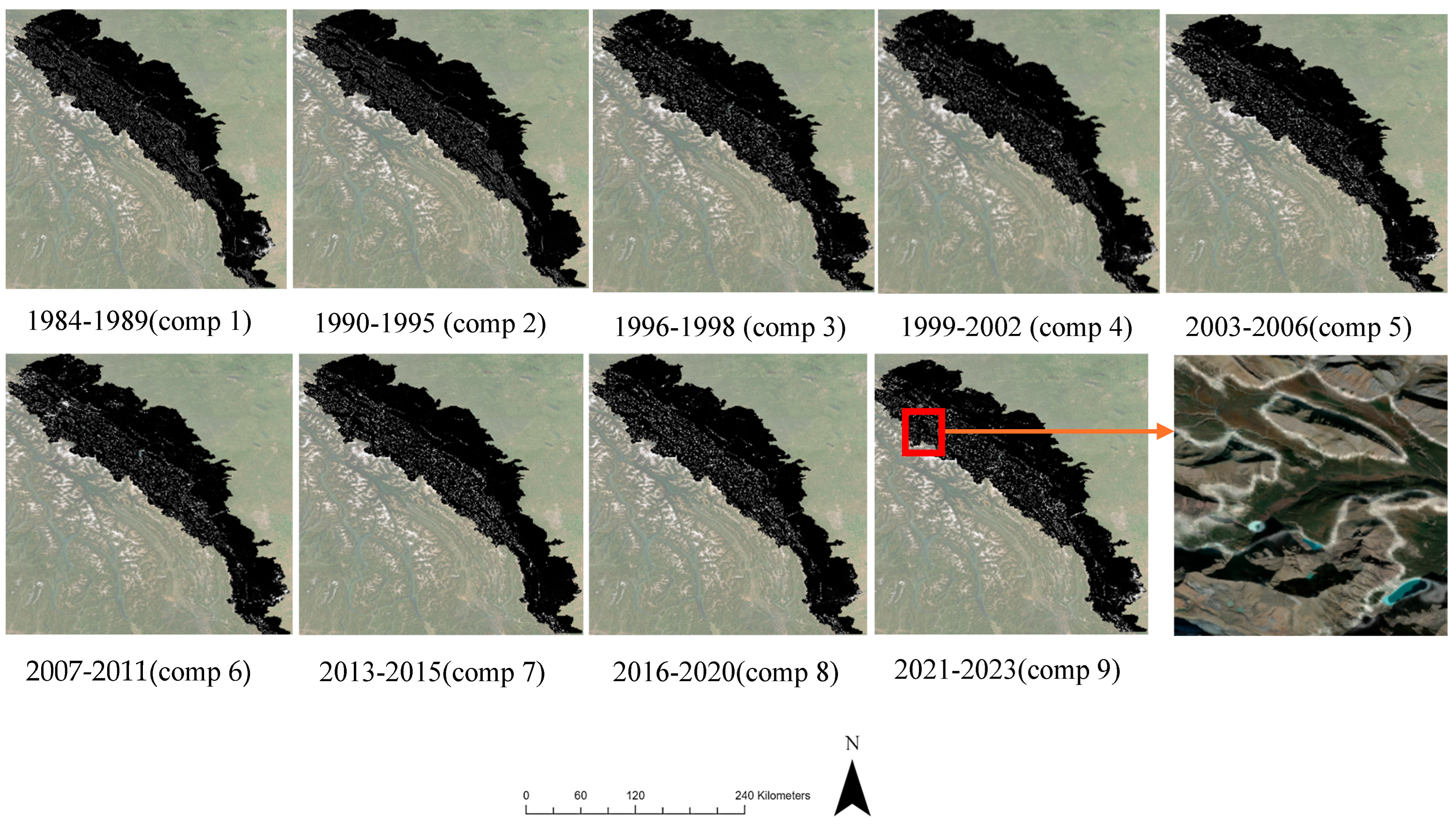

3.1. Alpine Treeline Ecotone Mapping over Nine Composite Intervals

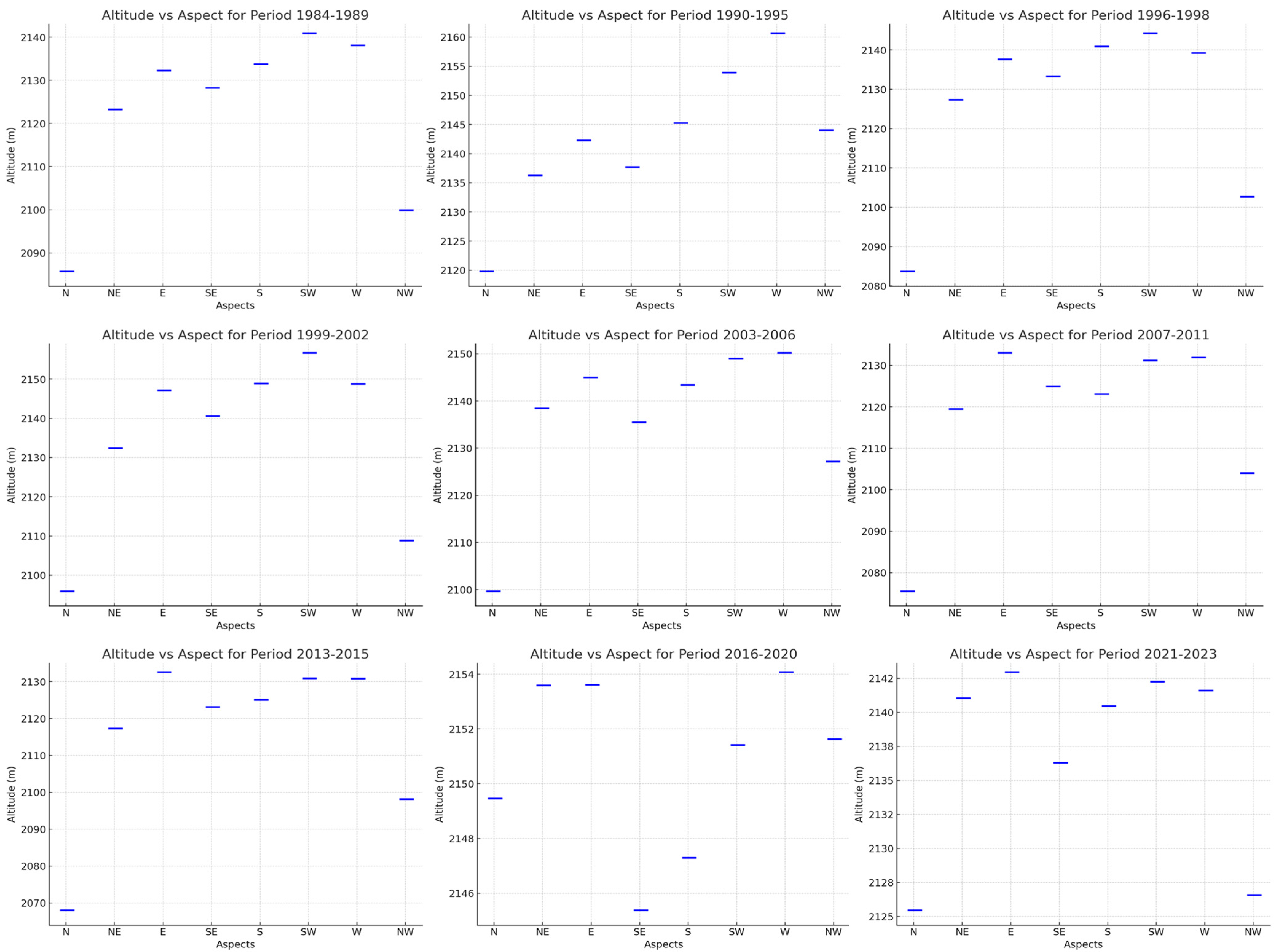

3.2. Variation in Altitude Across Different Aspects

3.3. Watershed-Scale Variation in Ecotonal Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Utility of the ATEI in Monitoring Climate-Driven Transitions in Mountain Ecosystems

4.2. ATE Expansion and Stability over Time

4.3. Elevational Differences Among Slope Aspects

4.4. Spatial Heterogeneity in Watershed-Level Ecotonal Change

4.5. Drivers and Implications of ATE Migration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Körner, C. Alpine Treelines; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978-3-0348-0395-3. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmeier, F.; Broll, G. Sensitivity and Response of Northern Hemisphere Altitudinal and Polar Treelines to Environmental Change at Landscape and Local Scales. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005, 14, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechler, L.; Rixen, C.; Bebi, P.; Bavay, M.; Marty, M.; Barbeito, I.; Dawes, M.A.; Hagedorn, F.; Krumm, F.; Möhl, P.; et al. Five Decades of Ecological and Meteorological Data Enhance the Mechanistic Understanding of Global Change Impacts on the Treeline Ecotone in the European Alps. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 355, 110126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, G.; Bie, X.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, J.-J.; Shi, S.; Zhang, T.; Peng, P.-H. Seasonal Snow Cover Patterns Explain Alpine Treeline Elevation Better than Temperature at Regional Scale. For. Ecosyst. 2023, 10, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.N.; Elliott, G.P.; Schliep, E.M. Seasonal Temperature–Moisture Interactions Limit Seedling Establishment at Upper Treeline in the Southern Rockies. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.; Wang, Y.; Piao, S.; Lu, X.; Camarero, J.J.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, L.; Ellison, A.M.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J. Species Interactions Slow Warming-Induced Upward Shifts of Treelines on the Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4380–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germino, M.J.; Smith, W.K.; Resor, A.C. Conifer Seedling Distribution and Survival in an Alpine-Treeline Ecotone. Plant Ecol. 2002, 162, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesbauer, H.; Bevington, A. Recent Changes in Forest Structure and Growth at the Alpine-treeline Ecotone in the Rocky and Columbia Mountains of Central British Columbia, Canada. J. Biogeogr. 2024, 51, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsch, M.A.; Hulme, P.E.; McGlone, M.S.; Duncan, R.P. Are Treelines Advancing? A Global Meta-analysis of Treeline Response to Climate Warming. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, C.; Foster, J.R.; Weiskittel, A.; D’Amato, A.W.; Simons-Legaard, E. Integrating Historical Observations Alters Projections of Eastern North American Spruce–Fir Habitat under Climate Change. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbu, J.A.; St Louis, V.L.; Emmerton, C.A.; Tank, S.E.; Criscitiello, A.S.; Silins, U.; Bhatia, M.P.; Cavaco, M.A.; Christenson, C.; Cooke, C.A.; et al. A Comprehensive Biogeochemical Assessment of Climate-Threatened Glacial River Headwaters on the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.L.; Gedalof, Z. Limited Prospects for Future Alpine Treeline Advance in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 4489–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roush, W. A Substantial Upward Shift of the Alpine Treeline Ecotone in the Southern Canadian Rocky Mountains. Master’s Thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, D.R.; Hopkinson, C. Modeling Watershed-Scale Historic Change in the Alpine Treeline Ecotone Using Random Forest. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 46, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C.A.; Emmerton, C.A.; Drevnick, P.E. Legacy Coal Mining Impacts Downstream Ecosystems for Decades in the Canadian Rockies. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 344, 123328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebi, P.; Kulakowski, D.; Veblen, T.T. Interactions between Fire and Spruce Beetles in a Subalpine Rocky Mountain Forest Landscape. Ecology 2003, 84, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, R.; Germain, R.R.; Bennett, J.R.; Reo, N.J.; Arcese, P. Vertebrate Biodiversity on Indigenous-Managed Lands in Australia, Brazil, and Canada Equals That in Protected Areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.P.; Coops, N.C.; Nelson, T.; Wulder, M.A.; Ronnie Drever, C. Integrating Accessibility and Intactness into Large-Area Conservation Planning in the Canadian Boreal Forest. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 167, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venier, L.A.; Thompson, I.D.; Fleming, R.; Malcolm, J.; Aubin, I.; Trofymow, J.A.; Langor, D.; Sturrock, R.; Patry, C.; Outerbridge, R.O.; et al. Effects of Natural Resource Development on the Terrestrial Biodiversity of Canadian Boreal Forests. Environ. Rev. 2014, 22, 457–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhood, D.W.; Swayer, M.; Haskines, W. Historical Risk Analysis of Watershed Disturbance in the Southern East Slopes Region of Alberta, Canada. In Proceedings of the Canada; Forest-Land-Fish Conference II, Edmenton, AB, Canada, 28 April 2004; pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmking, M.; Juday, G.P.; Barber, V.A.; Zald, H.S.J. Recent Climate Warming Forces Contrasting Growth Responses of White Spruce at Treeline in Alaska through Temperature Thresholds. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2004, 10, 1724–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudek, C.; Barni, E.; Stanchi, S.; D’Amico, M.; Pintaldi, E.; Freppaz, M. Mid and Long-Term Ecological Impacts of Ski Run Construction on Alpine Ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, T.; McCune, J.L. Vegetation Type and Trail Use Interact to Affect the Magnitude and Extent of Recreational Trail Impacts on Plant Communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofgaard, A.; Dalen, L.; Hytteborn, H. Tree Recruitment above the Treeline and Potential for Climate-driven Treeline Change. J. Veg. Sci. 2009, 20, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulakowski, D.; Veblen, T. Effect of Prior Disturbances on the Extent and Severity of Wildfire in Colorado Subalpine Forests. Ecology 2007, 88, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Shrestha, A.; Innes, J.L. Grassland Resilience to Woody Encroachment in North America and the Effectiveness of Using Fire in National Parks. Climate 2023, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Germino, M.J.; Johnson, D.M.; Reinhardt, K. The Altitude of Alpine Treeline: A Bellwether of Climate Change Effects. Bot. Rev. 2009, 75, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, A.G.; Graumlich, L.J.; Urban, D.L. Trends in Twentieth-Century Tree Growth at High Elevations in the Sierra Nevada and White Mountains, USA. The Holocene 2005, 15, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trant, A.; Higgs, E.; Starzomski, B.M. A Century of High Elevation Ecosystem Change in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, J.F.; Allen, C.D.; Franklin, J.F.; Frelich, L.E.; Harvey, B.J.; Higuera, P.E.; Mack, M.C.; Meentemeyer, R.K.; Metz, M.R.; Perry, G.L.; et al. Changing Disturbance Regimes, Ecological Memory, and Forest Resilience. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, B.J.; Rgnire, J.; Fettig, C.J.; Hansen, E.M.; Hayes, J.L.; Hicke, J.A.; Kelsey, R.G.; Negron, J.F.; Seybold, S.J. Climate Change and Bark Beetles of the Western United States and Canada: Direct and Indirect Effects. Bioscience 2010, 60, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, D.; Hopkinson, C. Repeat Oblique Photography Shows Terrain and Fire-Exposure Controls on Century-Scale Canopy Cover Change in the Alpine Treeline Ecotone. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.L.; Brown, R.; Daniels, L.; Kavanagh, T.; Gedalof, Z. Regional Variability in the Response of Alpine Treelines to Climate Change. Clim. Change 2020, 162, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthof, I.; Pouliot, D. Treeline Vegetation Composition and Change in Canada’s Western Subarctic from AVHRR and Canopy Reflectance Modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.K.; Coops, N.C.; Hermosilla, T.; Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C. Evidence of Vegetation Greening at Alpine Treeline Ecotones: Three Decades of Landsat Spectral Trends Informed by Lidar-Derived Vertical Structure. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 084022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Karger, D.N.; Wilson, A.M. Spatial Detection of Alpine Treeline Ecotones in the Western United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 240, 111672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, E.H. Flora of Alberta: A Manual of Flowering Plants, Conifers, Ferns, and Fern Allies Found Growing Without Cultivation in the Province of Alberta, Canada, 2nd ed.; John, G.P., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Parks. A Framework for Alberta’s Parks. Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation. In Natural Regions and Subregions of Alberta, 1st ed.; Alberta Parks: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2015; Volume 1, ISBN 978-1-4601-1362-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chaikowsky, C.L.A. Analysis of Alberta Temperature Observations and Estimates by Global Climate Models; Alberta Environment: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hayhone, K.; Stoner, A. Alberta’s Climate Future; ATMOS Research & Consulting: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Environment Canada. 1981–2010 Climate Normals & Averages; Environment Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data; Environment and Climate Change Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding, D.A.; Smith, P.; Davidson, B.; Harrison, R. Holocene Tree Line Changes in the Canadian Cordillera Are Controlled by Climate and Topography; Alberta Parks: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.; Anderson, M.; Belward, A.; Bindschadler, R.; Cohen, W.; Gao, F.; Goward, S.N.; Helder, D.; Helmer, E.; et al. Free Access to Landsat Imagery. Science 2008, 320, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, C.; White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A. Optical Remotely Sensed Time Series Data for Land Cover Classification: A Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 116, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masek, J.G.; Vermote, E.F.; Saleous, N.E.; Wolfe, R.; Hall, F.G.; Huemmrich, K.F.; Gao, F.; Kutler, J.; Lim, T.-K. A Landsat Surface Reflectance Dataset for North America, 1990–2000. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2006, 3, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.; Justice, C.; Claverie, M.; Franch, B. Preliminary Analysis of the Performance of the Landsat 8/OLI Land Surface Reflectance Product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Hobart, G.W.; Luther, J.E.; Hermosilla, T.; Griffiths, P.; Coops, N.C.; Hall, R.J.; Hostert, P.; Dyk, A.; et al. Pixel-Based Image Compositing for Large-Area Dense Time Series Applications and Science. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 40, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choler, P.; Michalet, R.; Callaway, R.M. Facilitation and Competition on Gradients in Alpine Plant Communities. Ecology 2001, 82, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, O.; Bunting, P.; Hardy, A.; McInerney, D. Sensitivity Analysis of the DART Model for Forest Mensuration with Airborne Laser Scanning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearborn, K.D.; Danby, R.K. Spatial Analysis of Forest–Tundra Ecotones Reveals the Influence of Topography and Vegetation on Alpine Treeline Patterns in the Subarctic. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 110, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Morris, C.S.; Belz, J.E. A Global Assessment of the SRTM Performance. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the Satellite-Derived NDVI to Assess Ecological Responses to Environmental Change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and Photographic Infrared Linear Combinations for Monitoring Vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, P.; Lemeshow, S. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Application, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 978-0-470-56350–2. [Google Scholar]

- Luckman, B.; Kavanagh, T. Impact of Climate Fluctuations on Mountain Environments in the Canadian Rockies. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2009, 29, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Fauria, M.; Johnson, E.A. Warming-Induced Upslope Advance of Subalpine Forest Is Severely Limited by Geomorphic Processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8117–8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, J.F.; Chapin, F.S. Effects of Soil Burn Severity on Post-Fire Tree Recruitment in Boreal Forest. Ecosystems 2006, 9, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Gameda, S.; Zhang, X.; De Jong, R. Changing Growing Season Observed in Canada. Clim. Change 2012, 112, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E. An Evaluation of Constraints to Treeline Advance Across Multiple Scales in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Aspect | Trend | Changing Altitude (m) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984–2023 | N | No | +40.21 | 0.201 |

| 1984–2023 | NE | No | +18.21 | 0.28 |

| 1984–2023 | E | No | +11.1 | 0.201 |

| 1984–2023 | SE | No | +8.5 | 0.088 |

| 1984–2023 | S | No | +7.1 | 0.594 |

| 1984–2023 | SW | No | +1.77 | 1 |

| 1984–2023 | W | No | +3.91 | 0.74 |

| 1984–2023 | NW | No | +27.12 | 0.166 |

| Watershed | Mean of Watershed Elevation (a.s.l) | Area (km2) | Area (%) | Increase (km2) | No Change (km2) | Decrease (km2) | Total Change | Total Observed | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Man | 1510.74 | 11,377.16 | 14.53 | 66.03 | 78.87 | 43.57 | 109.60 | 188.47 | 0.1001 |

| Bow | 1843.26 | 8883.66 | 18.60 | 246.30 | 204.18 | 169.45 | 415.75 | 619.93 | 0.0008 |

| Red Deer | 1695.30 | 4825.36 | 7.89 | 54.86 | 33.30 | 65.39 | 120.25 | 153.55 | 0.6306 |

| North Saskatchewan | 1768.89 | 17,027.27 | 27.84 | 258.58 | 176.10 | 221.98 | 480.56 | 656.66 | 0.2481 |

| Athabasca | 1681.04 | 19,038.45 | 31.13 | 262.71 | 311.31 | 189.23 | 451.94 | 763.25 | 0.0025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hooshyarkhah, B.; Johnson, D.L.; Spencer, L.; Ryait, H.S.; Chegoonian, A. Mapping Four Decades of Treeline Ecotone Migration: Remote Sensing of Alpine Ecotone Shifts on the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4004. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244004

Hooshyarkhah B, Johnson DL, Spencer L, Ryait HS, Chegoonian A. Mapping Four Decades of Treeline Ecotone Migration: Remote Sensing of Alpine Ecotone Shifts on the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4004. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244004

Chicago/Turabian StyleHooshyarkhah, Behnia, Dan L. Johnson, Locke Spencer, Hardeep S. Ryait, and Amir Chegoonian. 2025. "Mapping Four Decades of Treeline Ecotone Migration: Remote Sensing of Alpine Ecotone Shifts on the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4004. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244004

APA StyleHooshyarkhah, B., Johnson, D. L., Spencer, L., Ryait, H. S., & Chegoonian, A. (2025). Mapping Four Decades of Treeline Ecotone Migration: Remote Sensing of Alpine Ecotone Shifts on the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4004. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244004