Understanding Hydrological Changes at Chiang Saen in the Lancang–Mekong River by Integrating Satellite-Based Meteorological Observations into a Deep Learning Model

Highlights

- Driven by satellite-based meteorological dataset of MSWEP and MSWX, the developed deep learning model can accurately simulate natural streamflow at Chiang Saen station.

- Changes in streamflow for the period of 1979–2021 show great seasonal variabilities, while the contributions of climate changes and human activities vary among seasons.

- Global satellite-based meteorological products demonstrate sufficient accuracy for streamflow modeling using deep learning-based approaches, highlighting their great potential for streamflow simulation in data-sparse region lacking ground observation.

- The streamflow variability at Chiang Saen is governed by complex interactions between climate change and human activities, providing decision support for sustainable transboundary water resource management.

Abstract

1. Introduction

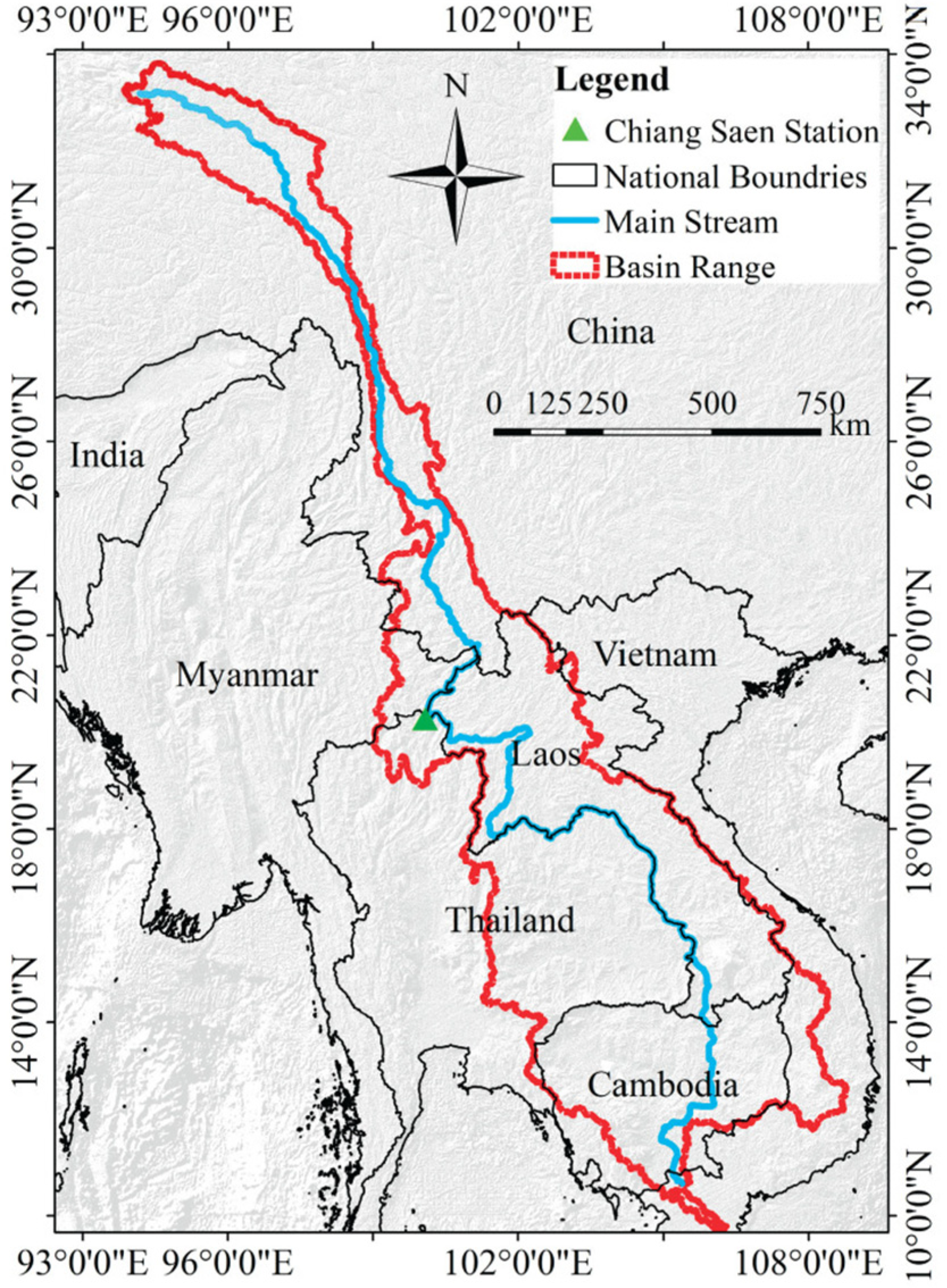

2. Overview of the Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

3.2. Trend Analysis Method

3.3. Periodic Analysis Method

3.4. Streamflow Simulation Using Long Short-Term Memory

3.5. Evaluation Method of the Influence of Climate Change and Human Activities on Streamflow

4. Results

4.1. Trend Analysis

4.2. Periodic Analysis

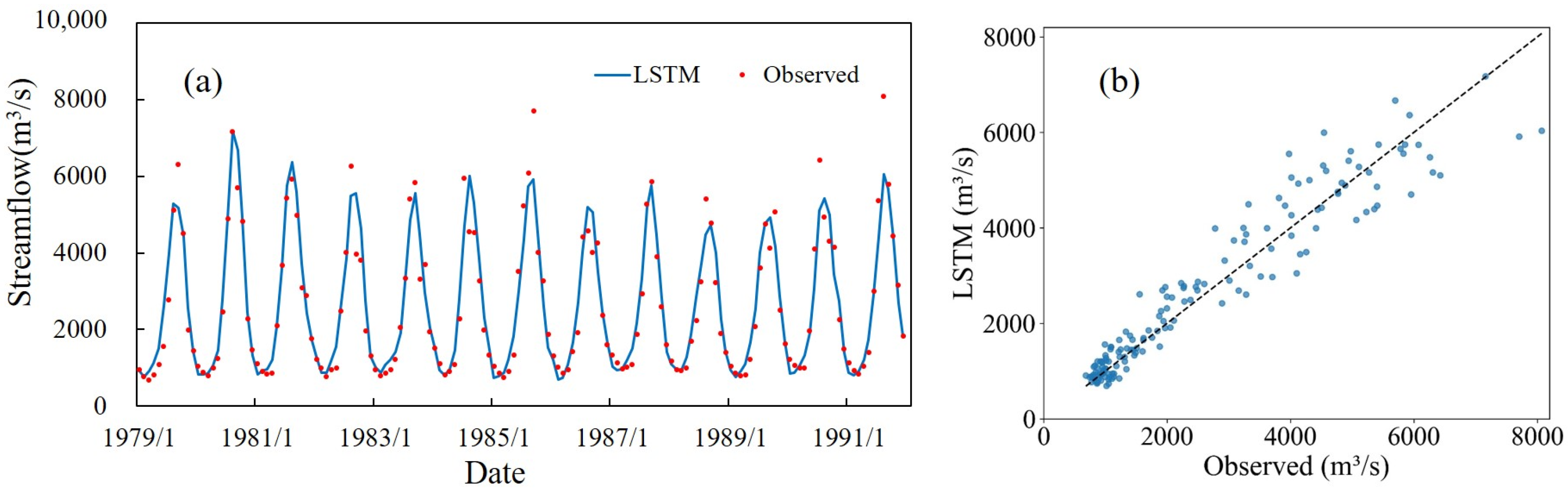

4.3. Streamflow Reconstruction

4.4. Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Streamflow

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, K.; Morovati, K.; Tian, F.; Yu, L.; Liu, B.; Olivares, M.A. Regional Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Altered Flow of the Lancang–Mekong River. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, R. Quantitative Assessment of the Impacts of Climate and Human Activities on Streamflow of the Lancang–Mekong River over the Recent Decades. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1024037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Zou, Z.; Deng, M.; Wang, W. The Influence of Anthropogenic Climate Change on Meteorological Drought in the Lancang–Mekong River Basin. J. Hydrol. 2023, 626, 130334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; She, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q. Future Projections of Flooding Characteristics in the Lancang–Mekong River Basin under Climate Change. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, L.; Han, F.; Zhang, C. Balancing Competing Interests in the Mekong River Basin via the Operation of Cascade Hydropower Reservoirs in China: Insights from System Modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Lv, Y. Research on Water Resource Modeling Based on Machine Learning Technologies. Water 2024, 16, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, E.; Tramblay, Y.; Grimaldi, S.; Salamon, P.; Dakhlaoui, H.; Dezetter, A.; Thiemig, V. Hydrological performance of the ERA5 reanalysis for flood modeling in Tunisia with the LISFLOOD and GR4J models. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 42, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbandsari, P.; Coulibaly, P. Inter-comparison of lumped hydrological models in data-scarce watersheds using different precipitation forcing data sets: Case study of Northern Ontario, Canada. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 31, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K.J.; Binley, A. The future of distributed models: Model training and uncertainty prediction. Hydrol. Process. 1992, 6, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlivanidis, I.; Jackson, B.; Mcintyre, N.; Wheater, H. Catchment scale hydrological modelling: A review of model types, training approaches and uncertainty analysis methods in the context of recent developments in technology and applications. Glob. Nest J. 2011, 13, 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, L.; Ma, C.; Sun, W. Ensemble Streamflow Simulations in a Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Basin Using a Deep Learning Method with Remote Sensing Precipitation Data as Input. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Qi, W.; Xu, C.-Y.; Kim, J.-S. Evaluation of Multi-Satellite Precipitation Datasets and Their ErrorPropagation in Hydrological Modeling in a Monsoon-Prone Region. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yong, B. A Preliminary Assessment of the Gauge-Adjusted Near-Real-Time GSMaP Precipitation Estimate over Mainland China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, R.; Srivastava, A.; Sarkar, S.; Khan, M.I. Revolutionizing the Future of Hydrological Science: Impact of Machine Learning and Deep Learning amidst Emerging Explainable AI and Transfer Learning. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 24, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Muñoz, D.F.; Orellana-Alvear, J.; Célleri, R. Enhancing Runoff Forecasting through the Integration of Satellite Precipitation Data and Hydrological Knowledge into Machine Learning Models. Nat. Hazards 2024, 121, 3915–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Feng, Q.; Cui, Y. Precipitation Recycling Impacts on Runoff in Arid Regions of China and Mongolia: A Machine Learning Approach. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 70, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seka, A.M.; Guo, H.; Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Bayable, E.; Ayele, G.T.; Workneh, H.T.; Bayouli, O.T.; Muhirwa, F.; Reda, K.W. Evaluating the Future Total Water Storage Change and Hydrological Drought under Climate Change over Lake Basins, East Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Shrestha, S.; Ghimire, S.; Sundaram, S.M.; Xue, W.; Virdis, S.G.; Maharjan, M. Application of Machine Learning Models in Assessing the Hydrological Changes under Climate Change in the Transboundary 3S River Basin. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 2902–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bao, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, C.; Jin, J. Trends and Changes in Hydrologic Cycle in the Huanghuaihai River Basin from 1956 to 2018. Water 2022, 14, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeditha, P.K.; Rathinasamy, M.; Neelamsetty, S.S.; Bhattacharya, B.; Agarwal, A. Investigation of Satellite Precipitation Product Driven Rainfall–Runoff Model Using Deep Learning Approaches in Two Different Catchments of India. J. Hydroinform. 2022, 24, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X. Changes of Terrestrial Water Storage during 1981–2020 over China Based on Dynamic-Machine Learning Model. J. Hydrol. 2023, 621, 129576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Ma, C.; Sun, W. Analyzing the Effects of Climate Change and Human Activities on Streamflow in a North China Arid Basin: A Machine Learning Perspective Considering Model Structural Uncertainty. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Long, D.; Zhao, J.; Lu, H.; Hong, Y. Observed changes in flow regimes in the Mekong River basin. J. Hydrol. 2017, 551, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Hu, M.; Chen, Y.; Cao, H.; Yue, W.; Zhao, X. Past, Present and Future Changes in the Annual Streamflow of the Lancang-Mekong River and Their Driving Mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, J.S.; Lacombe, G.; Arias, M.E. Hydropower dams in the Mekong River Basin: A review of their hydrological impacts. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Fisher, C.K.; Miralles, D.G.; Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; McVicar, T.R.; Adler, R.F. MSWEP V2 Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Precipitation: Methodology and Quantitative Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, C.; Ruben, G.B.; Wang, G. Assessing the uncertainties of four precipitation products for SWAT modeling in Mekong River Basin. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zeng, T.; Chen, Q.; Han, X.; Weng, X.; He, P.; Zhou, Z.; Du, Y. Spatio-temporal changes in daily extreme precipitation for the Lancang–Mekong River Basin. Nat. Hazards 2023, 115, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Jin, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, G.; Tang, L. Spatiotemporal Projections of Precipitation in the Lancang–Mekong River Basin Based on CMIP6 Models. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Larraondo, P.R.; McVicar, T.R.; Pan, M.; Dutra, E.; Miralles, D.G. MSWX: Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Bias-Corrected Meteorological Data Including Near-Real-Time Updates and Forecast Ensembles. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E710–E732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, A.; Morlet, J. Decomposition of Hardy Functions into Square Integrable Wavelets of Constant Shape. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1984, 15, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlet, J.; Arens, G.; Fourgeau, E.; Glard, D. Wave Propagation and Sampling Theory—Part I: Complex Signal and Scattering in Multilayered Media. Geophysics 1982, 47, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, D.; Engel, M.; Wohlmuth, B.; Labat, D.; Chiogna, G. Temporal Scale-Dependent Sensitivity Analysis for Hydrological Model Parameters Using the Discrete Wavelet Transform and Active Subspaces. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR028511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.Y.; Saber, A.; Arnillas, C.A.; Javed, A.; Richards, A.; Arhonditsis, G.B. Effects of Hydrological Forcing on Short- and Long-Term Water Level Fluctuations in Lake Huron–Michigan: A Continuous Wavelet Analysis. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, W. Study on a Mother Wavelet Optimization Framework Based on Change-Point Detection of Hydrological Time Series. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Fu, G.; He, R.; Yan, X.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A. Attribution for decreasing streamflow of the Haihe River basin, northern China: Climate variability or human activities? J. Hydrol. 2012, 460–461, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yin, X.A.; Yang, P.; Yang, Z. Assessment of contributions of climatic variation and human activities to streamflow changes in the Lancang River, China. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 2953–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, T.; Reece, S.; Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Gauch, M.; De Bruijn, J.; Kumar Sahu, R.; Greve, P.; Slater, L.; Dadson, S. Hydrological concept formation inside long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 26, 3079–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, P.; Wang, P.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Huo, Z. A novel hybrid deep learning framework for evaluating field evapotranspiration considering the impact of soil salinity. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NSE | KGE | R2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Validation | Training | Validation | Training | Validation | |

| T | 0.558 | 0.592 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.61 |

| T-1, T | 0.870 | 0.875 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| T-2, T-1, T | 0.916 | 0.901 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.90 |

| Yearly | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QBM (m3/s) | 2653.8 | 1056.6 | 4214.7 | 3914.9 | 1327.6 |

| QAM (m3/s) | 2532.0 | 1380.1 | 3869.4 | 3442.7 | 1373.2 |

| QAM − QBM (m3/s) | −121.8 | 323.6 | −345.3 | −472.2 | 45.6 |

| η | −4.6% | 30.6% | −8.2% | −12.1% | 3.4% |

| Yearly | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 25.4% | 40.8% | 31.3% | 9.8% | −63.9% |

| HA | 74.6% | 59.2% | 68.7% | 90.2% | 163.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Gu, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Yi, Z.; et al. Understanding Hydrological Changes at Chiang Saen in the Lancang–Mekong River by Integrating Satellite-Based Meteorological Observations into a Deep Learning Model. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244002

Zhang M, Wang J, Gu H, Zhou J, Wang W, Wang Y, Chen J, Yang X, Wang Q, Yi Z, et al. Understanding Hydrological Changes at Chiang Saen in the Lancang–Mekong River by Integrating Satellite-Based Meteorological Observations into a Deep Learning Model. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244002

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Muzi, Jinqiang Wang, Hongbin Gu, Jian Zhou, Weiwei Wang, Yicheng Wang, Juanjuan Chen, Xueqian Yang, Qiyue Wang, Zhiwen Yi, and et al. 2025. "Understanding Hydrological Changes at Chiang Saen in the Lancang–Mekong River by Integrating Satellite-Based Meteorological Observations into a Deep Learning Model" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244002

APA StyleZhang, M., Wang, J., Gu, H., Zhou, J., Wang, W., Wang, Y., Chen, J., Yang, X., Wang, Q., Yi, Z., Huo, Y., & Sun, W. (2025). Understanding Hydrological Changes at Chiang Saen in the Lancang–Mekong River by Integrating Satellite-Based Meteorological Observations into a Deep Learning Model. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244002