Multi-Method and Multi-Depth Geophysical Data Integration for Archaeological Investigations: First Results from the Greek City of Gela (Sicily, Italy)

Highlights

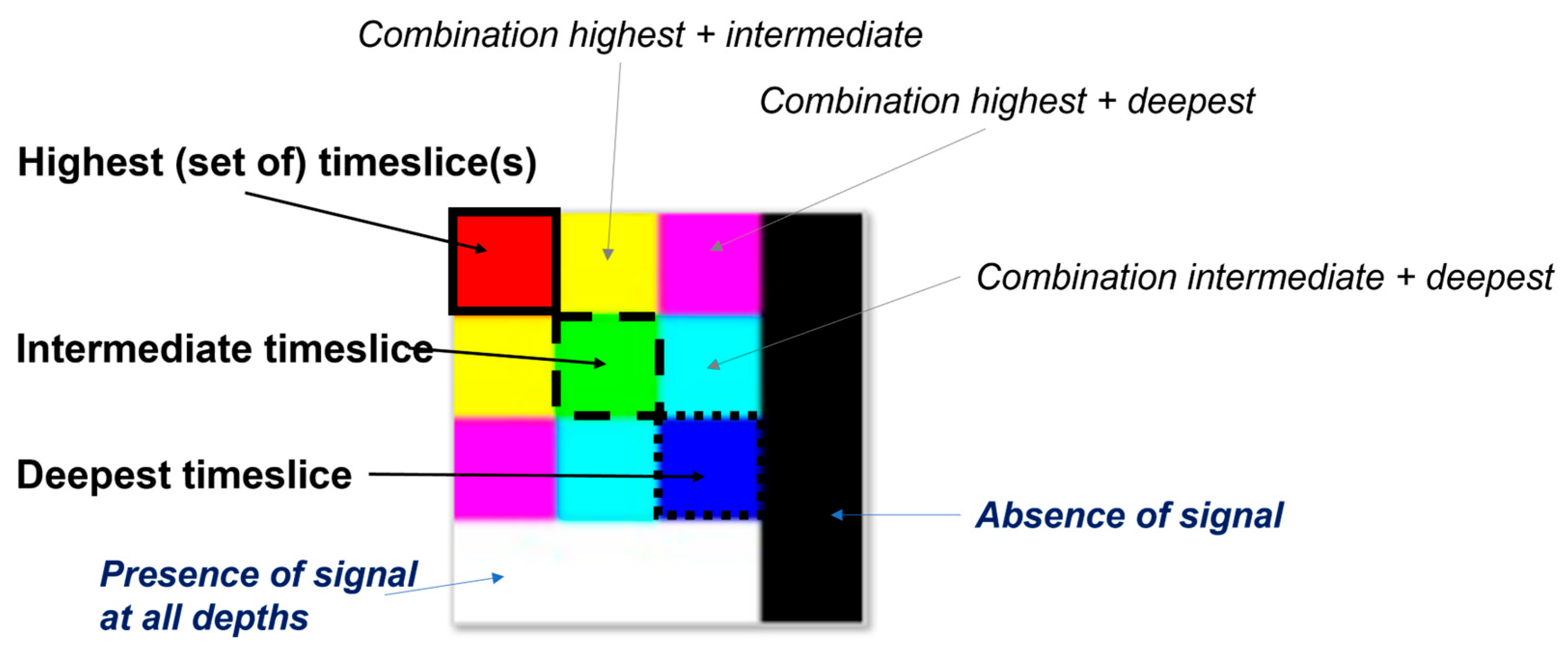

- A new tool/approach to inspect GPR data-cubes is designed, implemented and validated in a classical archaeological context. It consists of a multi-depth/multi-time holistic and parametric visualization of the datasets at different levels of processing, distinguishing the most significant signal patterns.

- A flexible investigation protocol is experimented with to study buried archaeological features depending on their specific physical properties (materials and geometries), including the new GPR interpretation-aiding tool, state of the art geophysics, and archaeological knowledge of the sites.

- The new tool proposed (RGB analysis of GPR data-cubes) provides a new parametric and controlled instrument in a global context of the synergistic analysis of GPR experimental datasets, integrating consolidated approaches with further reliable support to data interpretation.

- The application to two quite different archaeological areas of the RGB approach and the flexible investigation protocol provides guidance for approaches for different archaeological and diagnostic contexts.

Abstract

1. Introduction

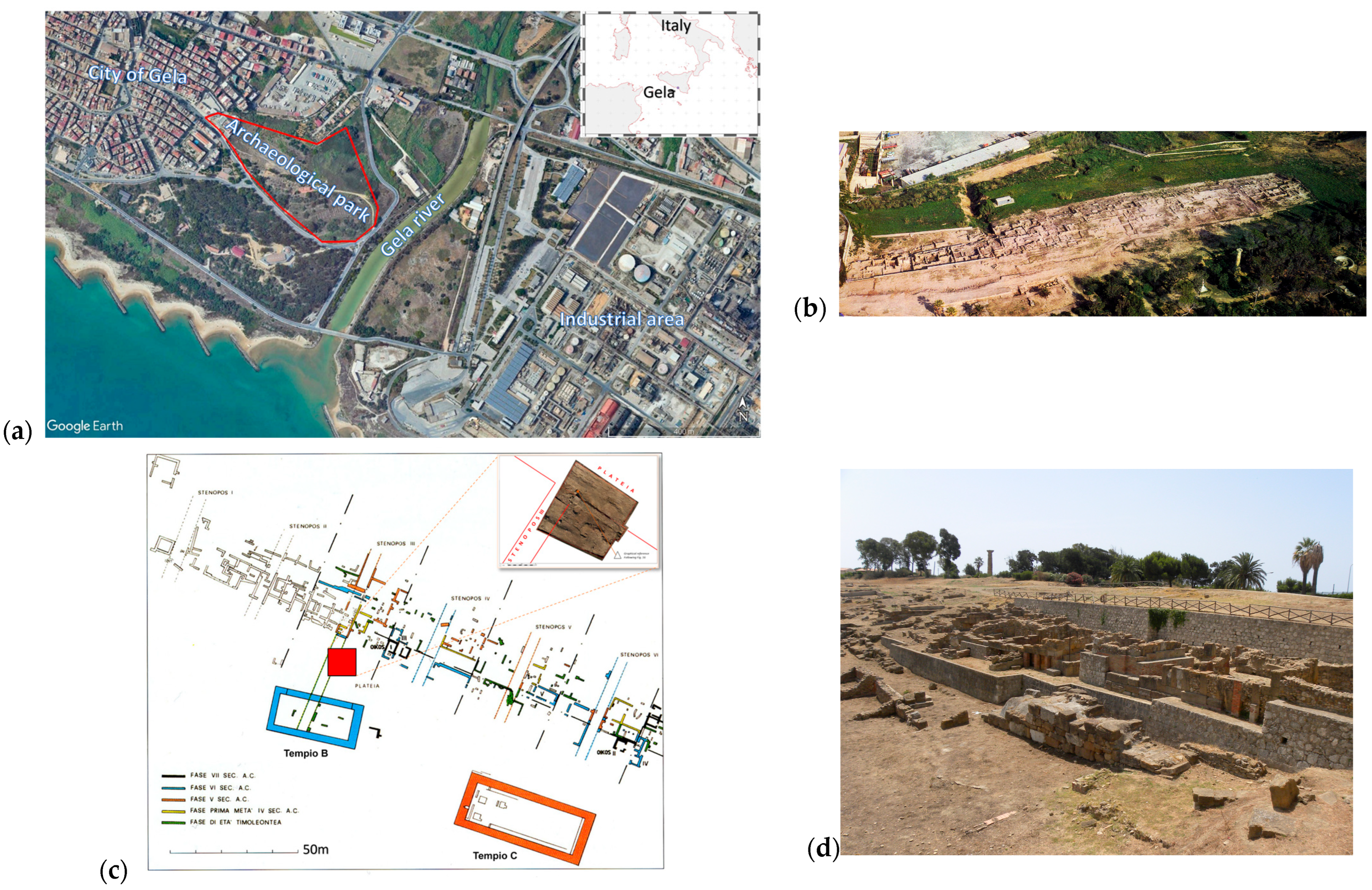

1.1. The Archeological Site

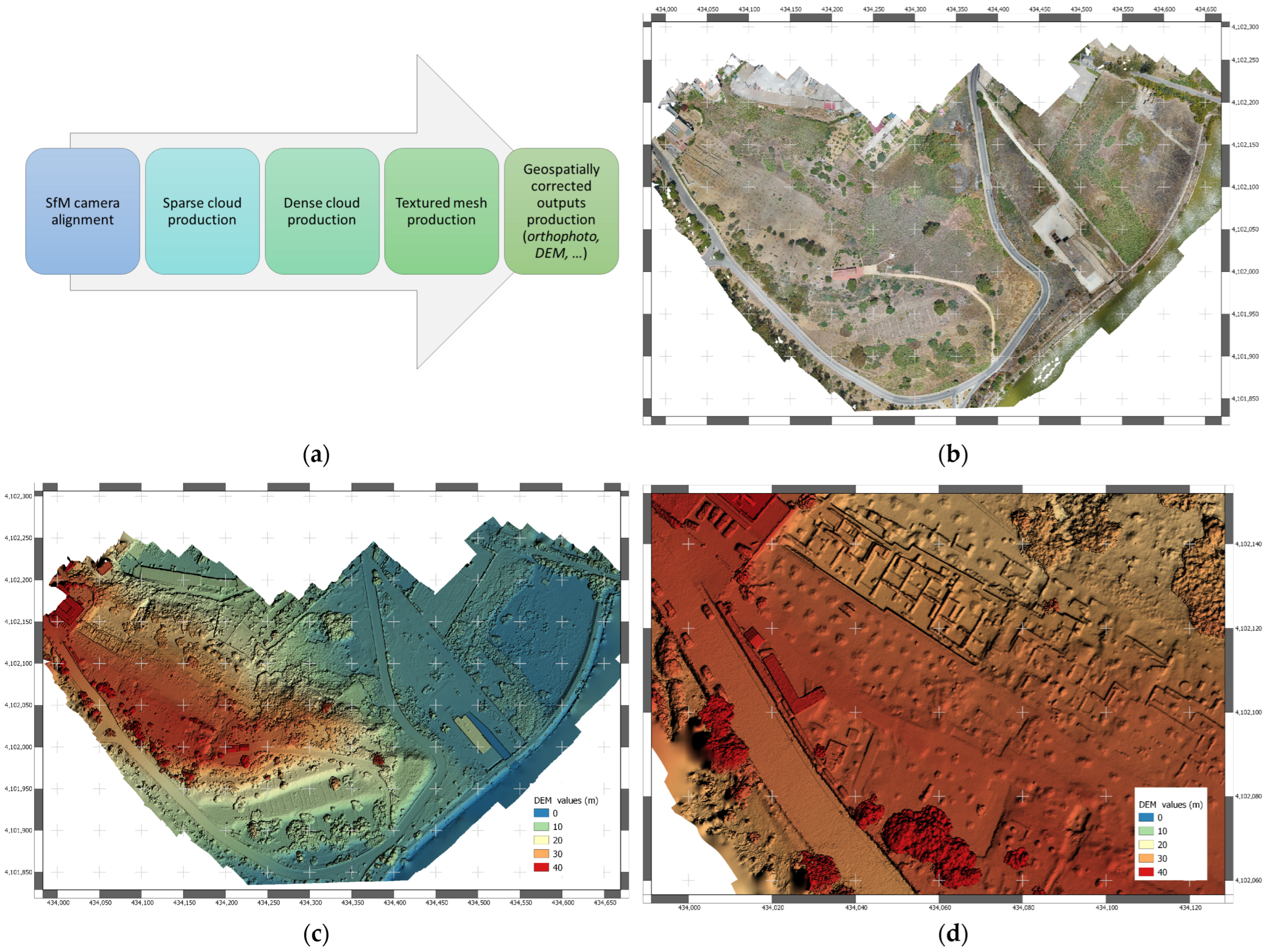

1.2. UAV Photogrammetry

2. Materials, Methods, and Techniques

2.1. Geophysical Data Collection

- Area 1, along the hypothetical westward continuation of the main road (plateia);

- Area 2, corresponding to the area of the so-called Temple B of the sanctuary.

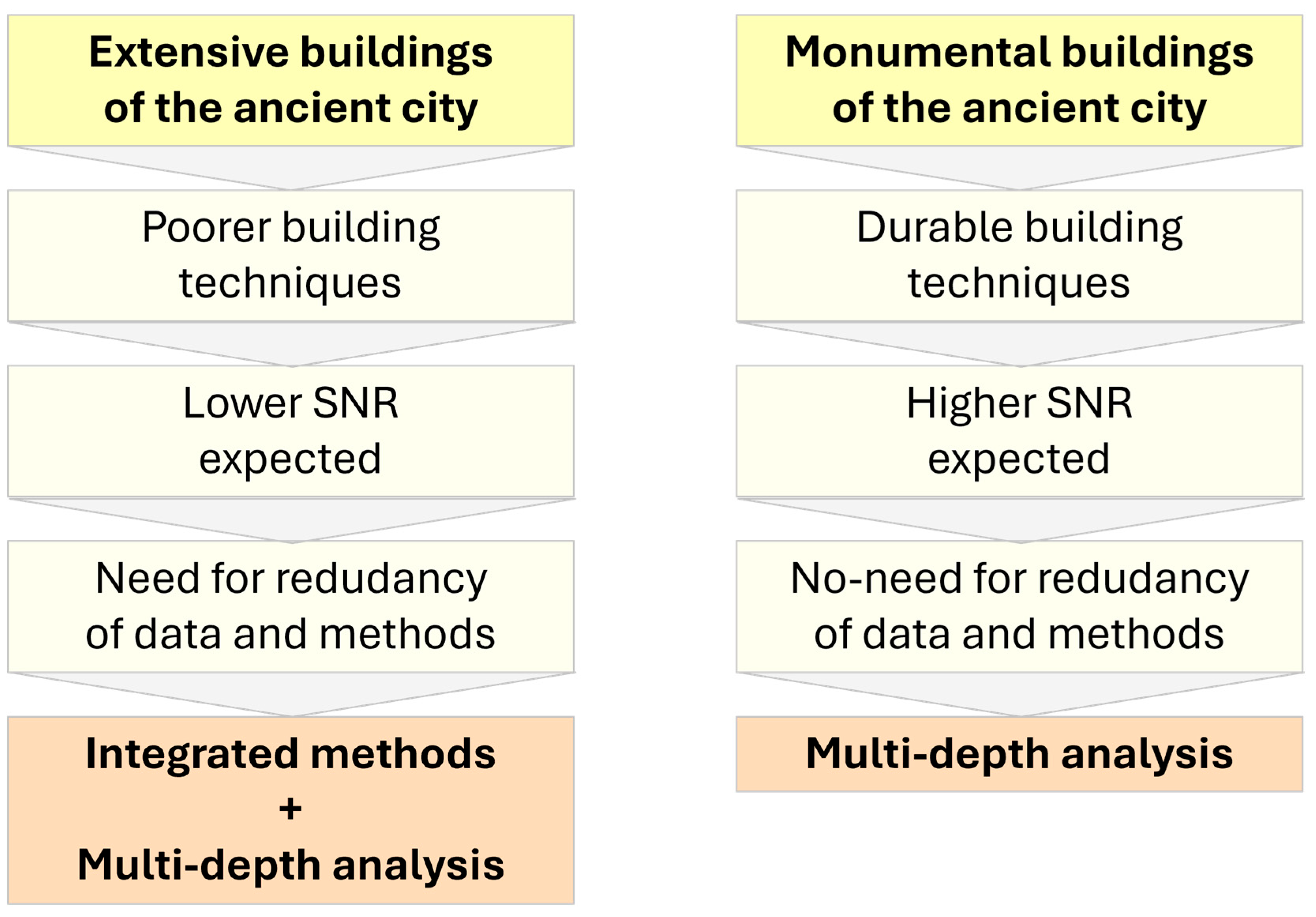

2.2. Integration of Diagnostic Methods

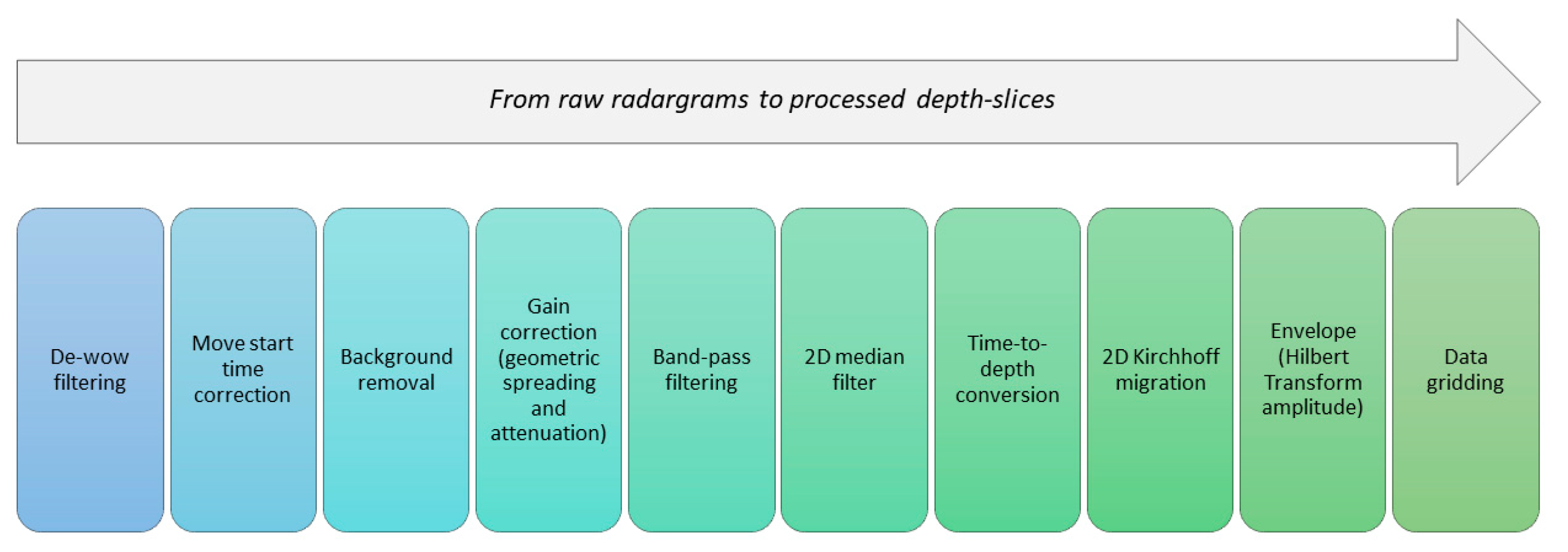

2.3. Visual Multi-Depth Integration of Geophysical Data

3. First Experimental Results

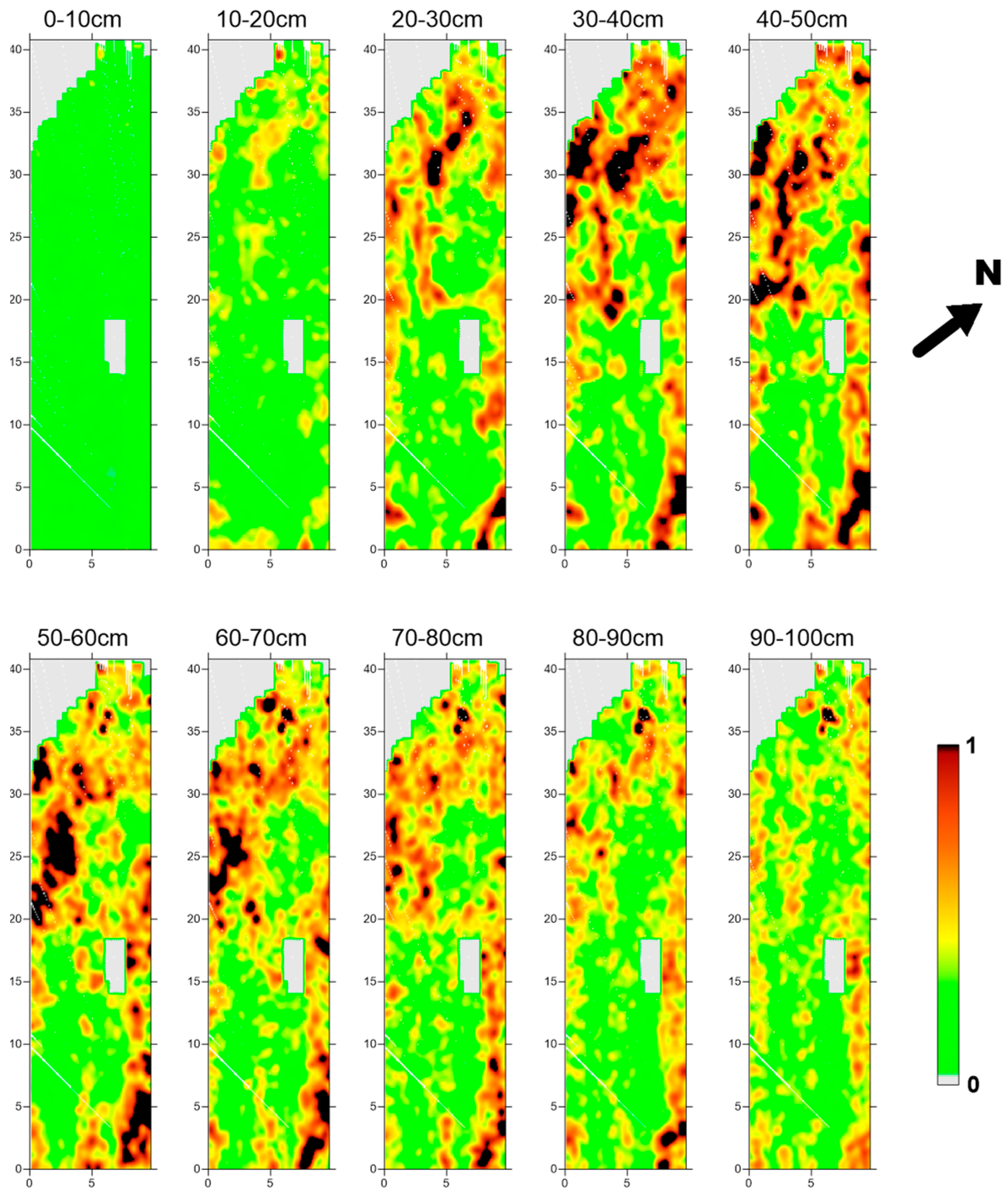

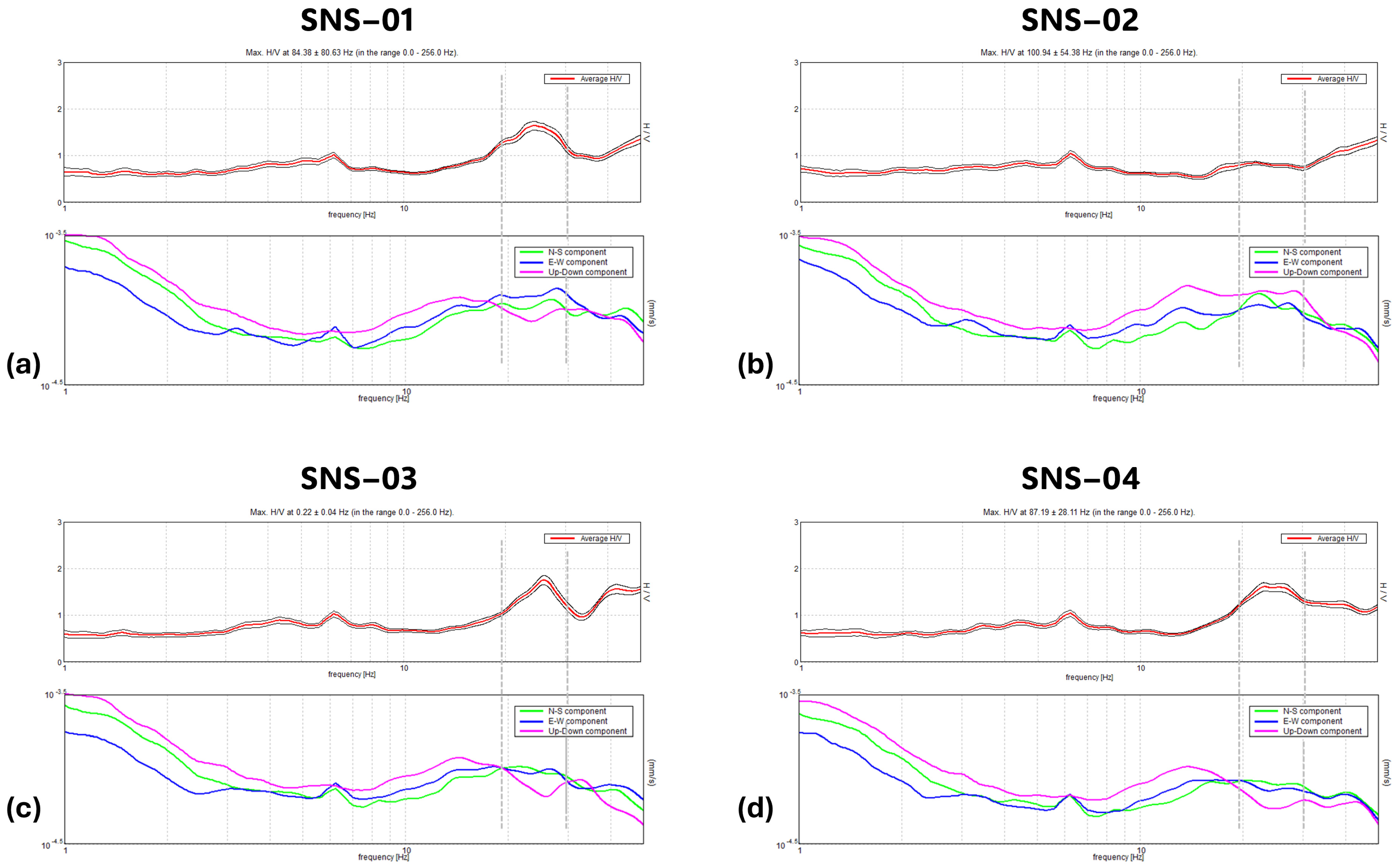

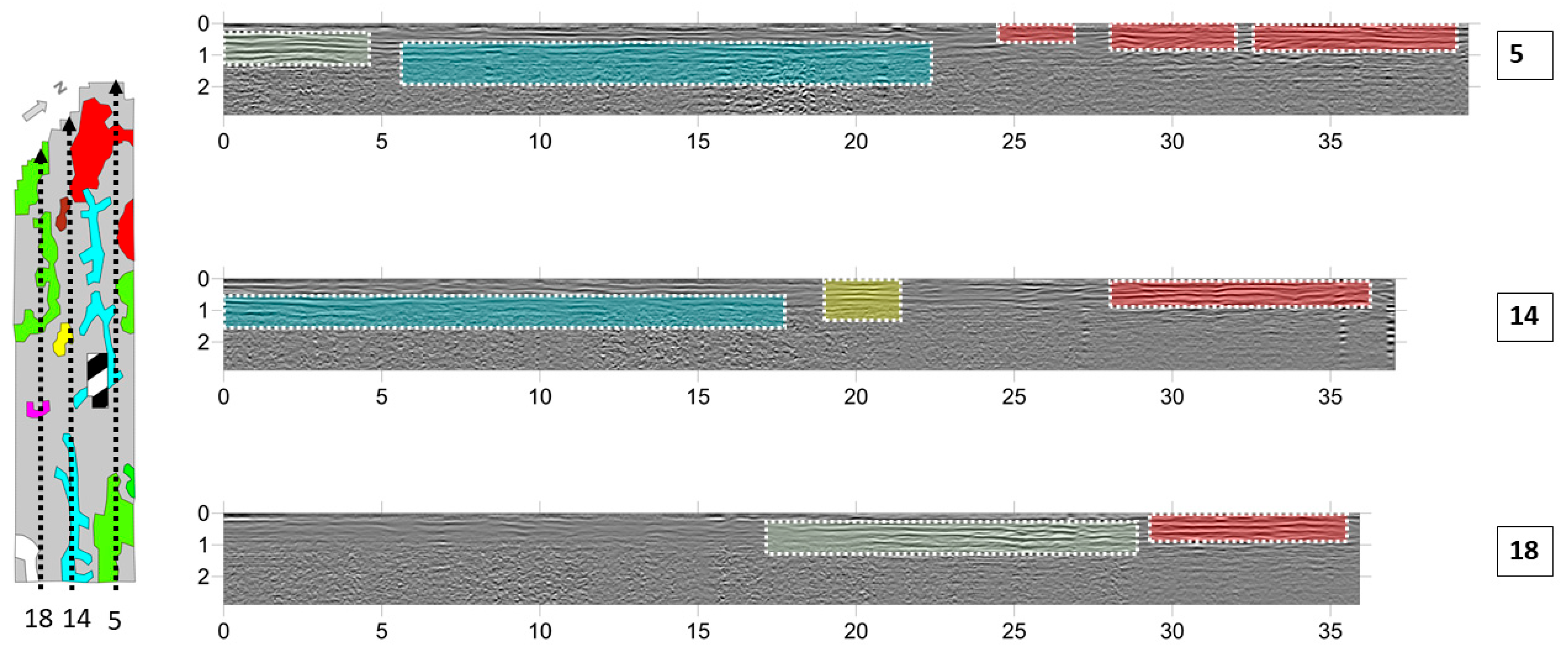

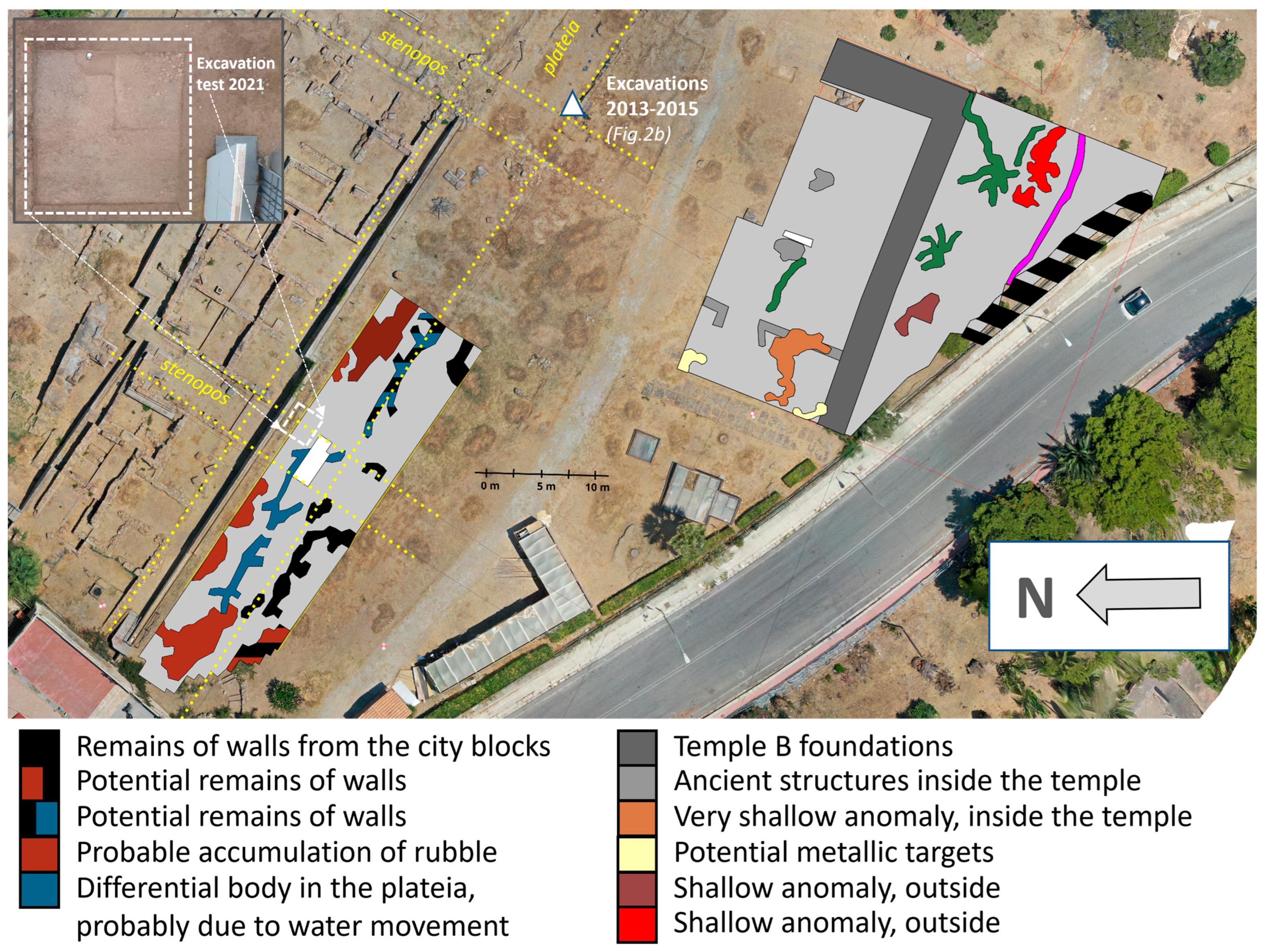

3.1. Geophysical Surveys of Area 1

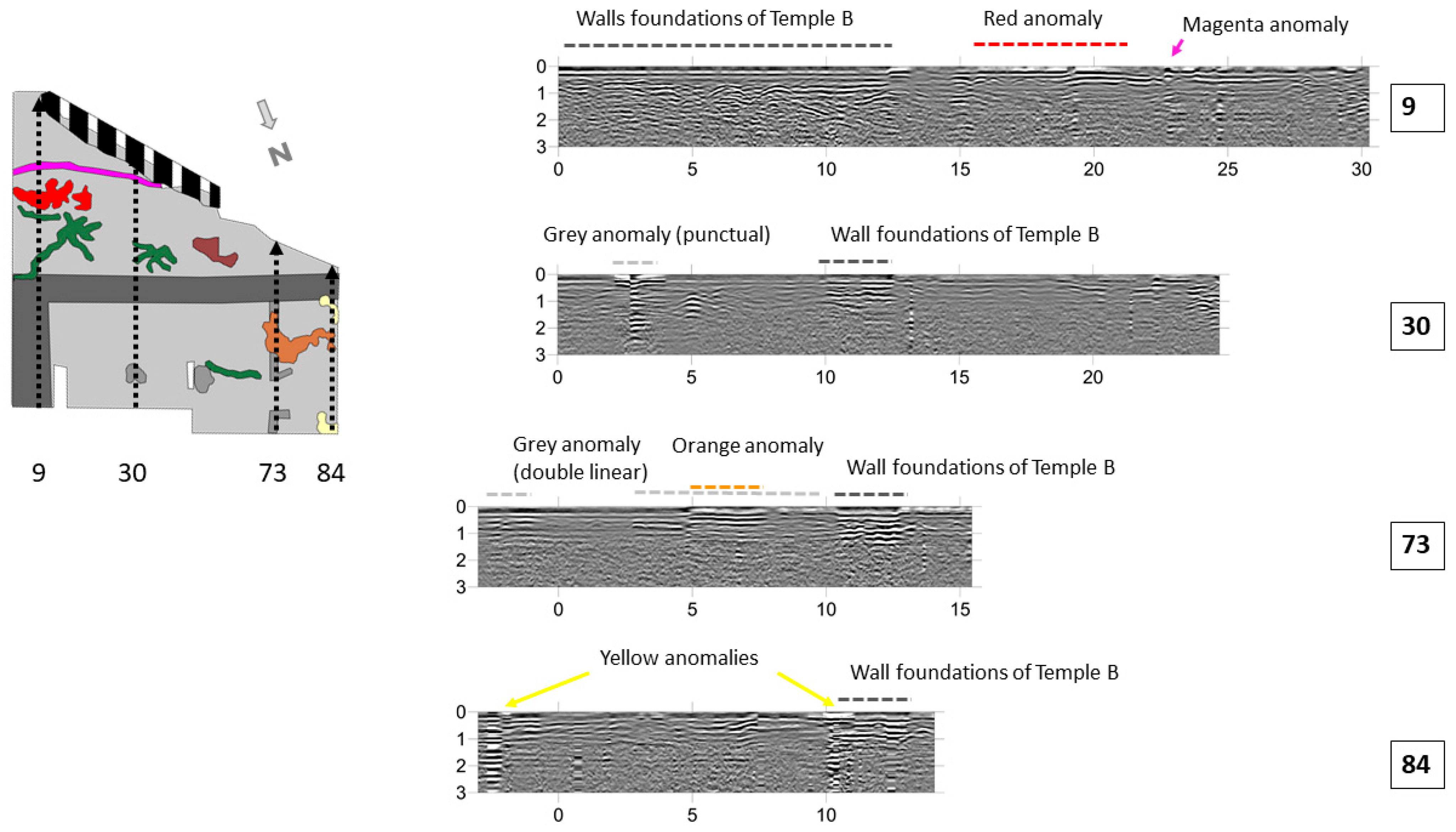

3.2. Geophysical Survey of Area 2

4. Data Integration and Calibration of the Results

4.1. Multi-Methods Integrated Comparison and Results

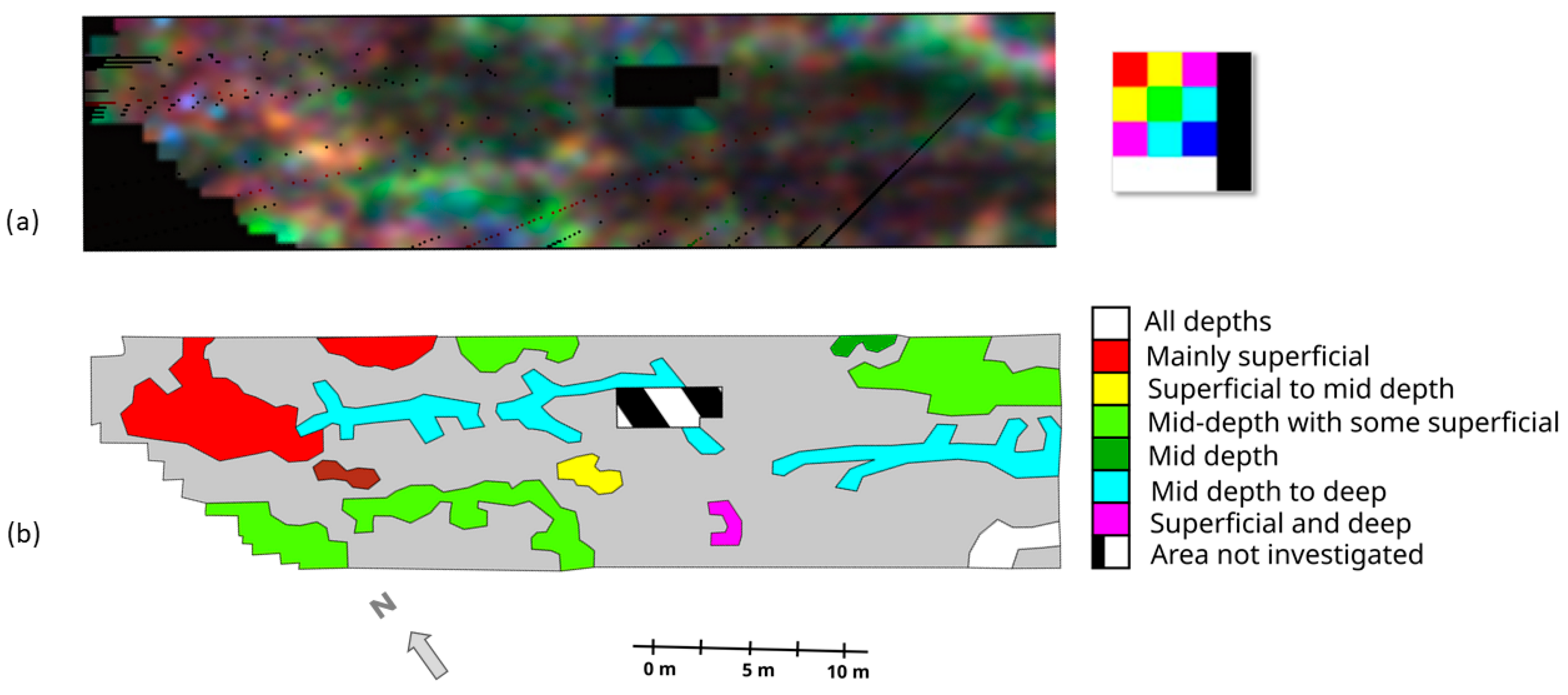

4.2. RGB Simultaneous Representation of GPR Depth Slices and Data Interpretation

Multi-Depth Analysis Calibration Through Radargrams Interpretation

5. Discussion: Coherence of the Geophysical Results with the Archeological Context

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piroddi, L.; Abu Zeid, N.; Calcina, S.V.; Capizzi, P.; Capozzoli, L.; Catapano, I.; Cozzolino, M.; D’Amico, S.; Lasaponara, R.; Tapete, D. Imaging Cultural Heritage at Different Scales: Part I, the Micro-Scale (Manufacts). Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Abu Zeid, N.; Calcina, S.V.; Capizzi, P.; Capozzoli, L.; Catapano, I.; Cozzolino, M.; D’Amico, S.; Lasaponara, R.; Tapete, D. Imaging Cultural Heritage at Different Scales: Part II, the Meso-Scale (Sites). Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.G.; Sarris, A.; Parkinson, W.A.; Gyucha, A.; Yerkes, R.W.; Duffy, P.R.; Tsourlos, P. Electrical resistivity tomography for the modelling of cultural deposits and geomophological landscapes at Neolithic sites: A case study from Southeastern Hungary. Archaeol. Prospect. 2014, 21, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Vignoli, G.; Trogu, A.; Deidda, G.P. Non-destructive Diagnostics of Architectonic Elements in San Giuseppe Calasanzio’s Church in Cagliari: A Test-case for Micro-geophysical Methods within the Framework of Holistic/integrated Protocols for Artefact Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 2018 Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (MetroArchaeo), Cassino, Italy, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fischanger, F.; Catanzari0ti, G.; Comina, C.; Sambuelli, L.; Morelli, G.; Barsuglia, F.; Ellaithy, A.; Porcelli, F. Geophysical anomalies detected by electrical resistivity tomography in the area surrounding Tutankhamun’s tomb. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Gentile, V.; Mauriello, P.; Peditrou, A. Non-destructive techniques for building evaluation in urban areas: The case study of the redesigning project of Eleftheria square (Nicosia, Cyprus). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Calcina, S.V.; Trogu, A.; Ranieri, G. Automated Resistivity Profiling (ARP) to explore wide archaeological areas: The prehistoric site of Mont’e Prama, Sardinia, Italy. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soupios, P.M.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Papadopoulos, N.; Saltas, V.; Andreadakis, A.; Vallianatos, F.; Sarris, A.; Makris, J.P. Use of engineering geophysics to investigate a site for a building foundation. J. Geophys. Eng. 2007, 4, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, T.; Zhou, B. A numerical comparison of 2D resistivity imaging with 10 electrode arrays. Geophys. Prospect. 2004, 52, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binley, A.; Slater, L. Resistivity and Induced Polarization: Theory and Applications to the Near-Surface Earth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gadallah, M.R.; Fisher, R. Exploration Geophysics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic Data Analysis: Processing, Inversion, and Interpretation of Seismic Data; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Karastathis, V.K.; Papamarinopoulos, S.P. The detection of King Xerxes’ Canal by the use of shallow reflection and refraction seis-mics—Preliminary results. Geophys. Prospect. 1997, 45, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deidda, G.P.; Balia, R. An ultrashallow SH-wave seismic reflection experiment on a subsurface ground model. Geophysics 2001, 66, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balia, R. Shallow reflection survey in the Selinunte National Archaeological Park (Sicily, Italy). Boll. Di Geofis. Teor. Ed. Appl. 1992, 34, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Karastathis, V.K.; Papamarinopoulos, S.; Jones, R.E. 2-D velocity structure of the buried ancient canal of Xerxes: An application of seismic methods in archaeology. J. Appl. Geophys. 2001, 47, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balia, R.; Pirinu, A. Geophysical surveying of the ancient walls of the town of Cagliari, Italy, by means of refraction and up-hole seismic tomography techniques. Archaeol. Prospect. 2018, 25, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirinu, A.; Balia, R.; Piroddi, L.; Trogu, A.; Utzeri, M.; Vignoli, G. Deepening the knowledge of military architecture in an urban context through digital representations integrated with geophysical surveys. The city walls of Cagliari (Italy). In Proceedings of the Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (MetroArchaeo), Cassino, Italy, 22–24 October 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Nogoshi, M.; Igarashi, T. On the propagation characteristics of microtremors. J. Seism. Soc. Jpn. 1970, 23, 264–280. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y. A method for dynamic characteristics estimation of subsurface using microtremor on the ground surface. Railw. Tech. Res. Inst. Q. Rep. 1989, 30, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Sarris, A.; Yi, M.J.; Kim, J.H. Urban archaeological investigations using surface 3D ground penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tomography methods. Explor. Geophys. 2009, 40, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conyers, L.B.; Leckebusch, J. Geophysical archaeology research agendas for the future: Some ground-penetrating radar examples. Archaeol. Prospect. 2010, 17, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, S.; Campana, S. GPR investigation in different archaeological sites in Tuscany (Italy). Anal. Comp. Obtained results. Near Surf. Geophys. 2012, 10, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Forte, E.; Levi, S.T.; Pipan, M.; Tian, G. Improved high-resolution GPR imaging and characterization of prehistoric archaeological features by means of attribute analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 54, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinks, I.; Hinterleitner, A.; Neubauer, W.; Nau, E.; Löcker, K.; Wallner, M.; Gabler, M.; Filzwieser, R.; Wilding, J.; Schiel, H.; et al. Large-area high-resolution ground-penetrating radar measurements for archaeological prospection. Archaeol. Prospect. 2018, 25, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persico, R.; D’Amico, S.; Matera, L.; Colica, E.; De Giorgio, C.; Alescio, A.; Sammut, C.; Galea, P. GPR Investigations at St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta. Near Surf. Geophys. 2019, 17, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colica, E.; Antonazzo, A.; Auriemma, R.; Coluccia, L.; Catapano, I.; Ludeno, G.; D’Amico, S.; Persico, R. GPR investigation at the archaeological site of Le Cesine, Lecce, Italy. Information 2021, 12, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manataki, M.; Vafidis, A.; Sarris, A. GPR data interpretation approaches in archaeological prospection. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Rassu, M. Application of GPR Prospection to Unveil Historical Stratification inside Monumental Buildings: The Case of San Leonardo de Siete Fuentes in Santu Lussurgiu, Sardinia, Italy. Land 2023, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jol, H.M. Ground Penetrating Radar Theory and Applications, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J.M. An Introduction to Applied and Environmental Geophysics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, P. Gela: Scavi del 1900–1905. Monumenti Antichi 1906, 17, 5–758. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, P. Gela (Terranova di Sicilia). Nuovo tempio greco arcaico in contrada Molino a vento. Not. Scavi Antich. 1907, 4, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandini, P. La Terza Campagna di Scavo Sull’Acropoli di Gela (rapporto Preliminare). Kokalos 1961, 7, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandini, P. Topografia dei santuari e documentazione archeologica dei culti. Riv. dell’Istituto Naz. d’Archeol. Stor. dell’Arte 1968, XV, 20–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini, G. Gela: La Città Antica e il suo Territorio. Il Museo; Regione Siciliana, Ass. Reg. BB.CC.AA.: Palermo, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Canzanella, M.G.; Buongiovanni, A.M. Gela. In BTCGI VIII; Scuola Normale Superiore, École Française de Rome, Centre Jean Bérard: Pisa-Roma, 1990; Volume VIII, pp. 5–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini, G.s.v. Gela. In EAA; Treccani: Roma, Italy, 1994; Volume II, Suppl. 2, pp. 728–732. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo, G. Gela. In Magna Grecia. Città greche di Magna Grecia e Sicilia; D’Andria, F., Guzzo, P.G., Tagliamonte, G., Eds.; Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2012; pp. 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ingoglia, C.; Santostefano, A.; Spagnolo, G. Ricerche e studi dell’Università di Messina a Gela: Urbanistica, cronologia delle fasi di vita della città, produzioni artigianali, territorio. In L’Isola dei Tesori, Ricerca Archeologica e Nuove Acquisizioni; Parello, M.C., Ed.; Ante Quem: Bologna, Italy, 2024; pp. 463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Ingoglia, C. Nascita del paesaggio urbano a Gela: Rilettura cronologica e funzionale. In Schemata. La Città oltre la Forma; Brancato, R., Caliò, L.M., Figuera, M., Gerogiannis, G.M., Pappalardo, E., Todaro, S., Eds.; Università di Catania: Roma, Italy, 2022; pp. 93–121. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo, G. Sviluppo del paesaggio urbano a Gela: La maglia stradale e il perimetro dell’asty in età arcaica e classica. In Schemata. La Città Oltre la Forma; Brancato, R., Caliò, L.M., Figuera, M., Gerogiannis, G.M., Pappalardo, E., Todaro, S., Eds.; Università di Catania: Roma, Italy, 2022; pp. 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Gafà, A.D.V. L’urbanistica. In Sikanie. Storia e Civiltà della Sicilia Greca; Pugliese Carratelli, G., Ed.; Istituto Veneto di Arti Grafiche: Milano, Italy, 1985; pp. 361–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ingoglia, C. Le più antiche fasi di vita di Gela: Contesti e cultura materiale. In Ktiseis. Fondazioni d’Occidente. Intrecci Culturali tra Gela, Agrigento, Creta e Rodi; Caminneci, V., D’Acunto, M., Lambrugo, C., Parello, M.C., Eds.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 2024; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Santostefano, A. Gela, Molino a Vento. In Gli isolati I e II (Scavi Orlandini 1955–1961); Dipartimento di Civiltà Antiche e Moderne dell’Università degli Studi di Messina: Roma, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Colica, E.; Galone, L.; D’amico, S.; Gauci, A.; Iannucci, R.; Martino, S.; Pistillo, D.; Iregbeyen, P.; Valentino, G. Evaluating characteristics of an active coastal spreading area combining geophysical data with satellite, aerial, and unmanned aerial vehicles images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persico, R.; Colica, E.; Zappatore, T.; Giardino, C.; D’Amico, S. Ground-Penetrating Radar and Photogrammetric Investigation on Prehistoric Tumuli at Parabita (Lecce, Italy) Performed with an Unconventional Use of the Position Markers. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D.; Piro, S.S. GPR Remote Sensing in Archaeology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Persico, R. Introduction to Ground Penetrating Radar: Inverse Scattering and Data Processing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Loke, M.H.; Papadopoulos, N.; Wilkinson, P.B.; Oikonomou, D.; Simyrdanis, K.; Rucker, D.F. The inversion of data from very large three-dimensional electrical resistivity tomography mobile surveys. Geophys. Prospect. 2020, 68, 2579–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakirov, A.; Yanbukhtin, I.; Mamarozikov, T.; Alimukhamedov, I.; Omonova, F.; Musaev, U.; Oripov, N.; Aripjanov, O. ERT, GPR, and magnetic surveying: The case study of Khayrabadtepa settlement (Southern Uzbekistan). Acta IMEKO 2024, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trogu, A.; Ranieri, G.; Calcina, S.; Piroddi, L. The ancient Roman aqueduct of Karales (Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy): Applicability of geophysics methods to finding the underground remains. Archaeol. Prospect. 2014, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, I.M.; Bergers, R.; Tezkan, B. Archaeogeophysical exploration in Neuss-Norf, Germany using electrical resistivity tomography and magnetic data. Near Surf. Geophys. 2021, 19, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, S.; Mauriello, P.; Cammarano, F. Quantitative integration of geophysical methods for archaeological prospection. Archaeol. Prospect. 2000, 7, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J.; Strutt, K.; Keay, S.; Earl, G.; Kay, S. Geophysical prospection at Portus: An evaluation of an integrated approach to interpreting subsurface archaeological features. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference of the Computing Applications and Quantitative Methods Conference, Williamsburg, VI, USA, 22–26 March 2010; pp. 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Keay, S.; Earl, G.; Hay, S.; Kay, S.; Ogden, J.; Strutt, K.D. The role of integrated geophysical survey methods in the assessment of archaeological landscapes: The case of Portus. Archaeol. Prospect. 2009, 16, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piga, C.; Piroddi, L.; Pompianu, E.; Ranieri, G.; Stocco, S.; Trogu, A. Integrated geophysical and aerial sensing methods for archaeology: A case history in the Punic Site of Villamar (Sardinia, Italy). Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 10986–11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persico, R.; Piro, S.; Linford, N. (Eds.) Innovation in Near-Surface Geophysics: Instrumentation, Application, and Data Processing Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dentith, M.; Mudge, S.T. Geophysics for the Mineral Exploration Geoscientist; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, D.K. Near-Surface Geophysics; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, M.E. Near-Surface Applied Geophysics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.R. Essentials of geophysical data processing. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Georgoula, O.; Kaimaris, D.; Tsakiri-Strati, M.; Patias, P. From the aerial photo to high resolution satellite image. Tools for the archaeological research. In ISPRS Archives–XXth ISPRS Congress Technical Commission VII (No. IKEECONF-2015-1378, pp. 1055–1060); Aristotle University of Thessaloniki: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lasaponara, R.; Masini, N. Detection of archaeological crop marks by using satellite QuickBird multispectral imagery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarris, A.; Papadopoulos, N.; Agapiou, A.; Salvi, M.C.; Hadjimitsis, D.G.; Parkinson, W.A.; Yerkes, R.W.; Gyucha, A.; Duffy, P.R. Integration of geophysical surveys, ground hyperspectral measurements, aerial and satellite imagery for archaeological prospection of prehistoric sites: The case study of Vésztő-Mágor Tell, Hungary. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 1454–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Ranieri, G.; Cogoni, M.; Trogu, A.; Loddo, F. Time and spectral multiresolution remote sensing for the study of ancient wall drawings at san salvatore hypogeum, Italy. In Proceedings of the 22nd European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Near Surface Geoscience 2016, Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 September 2016; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Agapiou, A.; Alexakis, D.D.; Sarris, A.; Hadjimitsis, D.G. Orthogonal Equations of Multi-Spectral Satellite Imagery for the Identification of Un-Excavated Archaeological Sites. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6560–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Calcina, S.V.; Fiorino, D.R.; Grillo, S.; Trogu, A.; Vignoli, G. Geophysical and remote sensing techniques for evaluating historical stratigraphy and assessing the conservation status of defensive structures heritage: Preliminary results from the military buildings at San Filippo Bastion, Cagliari, Italy. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., et al., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12255, pp. 944–959. [Google Scholar]

- Piroddi, L.; Calcina, S.V.; Trogu, A.; Vignoli, G. Towards the definition of a low-cost toolbox for qualitative inspection of painted historical vaults by means of modified DSLR cameras, open source programs and signal processing techniques. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., et al., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12255, pp. 971–991. [Google Scholar]

- Vergnano, A.; de Vingo, P.; Rosso, G.; Uggè, S.; Comina, C. Integration of satellite and aerial images with multichannel GPR surveys in the archaeological area of Augusta Bagiennorum for an improved description of the urban setting. J. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 232, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellaro, S.; Imposa, S.; Barone, F.; Chiavetta, F.; Gresta, S.; Mulargia, F. Georadar and passive seismic survey in the Roman Amphitheatre of Catania (Sicily). J. Cult. Herit. 2008, 9, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucci, G.; Persico, R.; De Giorgi, L.; Lazzari, M.; Colica, E.; Martino, S.; Iannucci, R.; D’Amico, S. Stability Assessment and Geomorphological Evolution of Sea Natural Arches by Geophysical Measurement: The Case Study of Wied Il-Mielaħ Window (Gozo, Malta). Sustainability 2021, 13, 12538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzera, F.; D’Amico, S.; Colica, E.; Viccaro, M. Ambient vibration measurements to support morphometric analysis of a pyroclastic cone. Bull. Volcanol. 2019, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galone, L.; Panzera, F.; Colica, E.; Fucks, E.; Carol, E.; Cellone, F.; Rivero, L.; Agius, M.R.; D’amico, S. A Seismic Monitoring Tool for Tidal-Forced Aquifer Level Changes in the Río de la Plata Coastal Plain, Argentina. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galone, L.; D’Amico, S.; Colica, E.; Iregbeyen, P.; Galea, P.; Rivero, L.; Villani, F. Assessing Shallow Soft Deposits through Near-Surface Geophysics and UAV-SfM: Application in Pocket Beaches Environments. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.R.; Cheng, T.; Vantassel, J.P.; Manuel, L. A statistical representation and frequency-domain window-rejection algorithm for single-station HVSR measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 221, 2170–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Moro, G.; Panza, G.F. Multiple-peak HVSR curves: Management and statistical assessment. Eng. Geol. 2022, 297, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunedei, E.; Albarello, D. Theoretical HVSR curves from full wavefield modelling of ambient vibrations in a weakly dissipative layered Earth. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 181, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Cox, B.R.; Vantassel, J.P.; Manuel, L. A statistical approach to account for azimuthal variability in single-station HVSR measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 223, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkaya, M. Feasibility of Utilizing Continuous Records from Weak And Strong-Motion Recorder Channels of Permanent Stations for Horizontal To Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR) Analysis During Calm-Day Conditions. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2025, 182, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistillo, D.; Colica, E.; D’Amico, S.; Farrugia, D.; Feliziani, F.; Galone, L.; Iannucci, R.; Martino, S. Engineering Geological and Geophysical Investigations to Characterise the Unstable Rock Slope of the Sopu Promontory (Gozo, Malta). Geosciences 2024, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galone, L.; Villani, F.; Colica, E.; Pistillo, D.; Baccheschi, P.; Panzera, F.; Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; D’Amico, S. Integrating near-surface geophysical methods and remote sensing techniques for reconstructing fault-bounded valleys (Mellieha valley, Malta). Tectonophysics 2024, 875, 230263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Instrument | Type/Configuration | Acquisition Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) | Cobra CBD (shielded) | Single antenna, reflection mode | GPR Area 1 and 2 Central Frequency: 400 MHz (area 1) 800 MHz (area 2) Time window: 50 ns Trace interval: 0.05 m Lateral distance between the lines: 0.40 m |

| Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) | ELECTRA Multichannel Digital Resistivimeter (MoHo srl) | 64-channel array | ERT Area 1 Electrode spacing: 0.5 m Number of electrodes: 64 Array type: Wenner, dipole–dipole and Schlumberger |

| Horizontal to Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR) | Tromino seismograph (MoHo srl) | Passive Single-station measurements | H/V Area 1 Sampling frequency: 128 Hz Recording time: 20 min per station Number of stations: 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piroddi, L.; Colica, E.; D’Amico, S.; Galone, L.; Ingoglia, C.; Spagnolo, G.; Santostefano, A.; Zurla, L.; Crupi, A.; Lanza, S.; et al. Multi-Method and Multi-Depth Geophysical Data Integration for Archaeological Investigations: First Results from the Greek City of Gela (Sicily, Italy). Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213561

Piroddi L, Colica E, D’Amico S, Galone L, Ingoglia C, Spagnolo G, Santostefano A, Zurla L, Crupi A, Lanza S, et al. Multi-Method and Multi-Depth Geophysical Data Integration for Archaeological Investigations: First Results from the Greek City of Gela (Sicily, Italy). Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(21):3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213561

Chicago/Turabian StylePiroddi, Luca, Emanuele Colica, Sebastiano D’Amico, Luciano Galone, Caterina Ingoglia, Grazia Spagnolo, Antonella Santostefano, Lorenzo Zurla, Antonio Crupi, Stefania Lanza, and et al. 2025. "Multi-Method and Multi-Depth Geophysical Data Integration for Archaeological Investigations: First Results from the Greek City of Gela (Sicily, Italy)" Remote Sensing 17, no. 21: 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213561

APA StylePiroddi, L., Colica, E., D’Amico, S., Galone, L., Ingoglia, C., Spagnolo, G., Santostefano, A., Zurla, L., Crupi, A., Lanza, S., & Randazzo, G. (2025). Multi-Method and Multi-Depth Geophysical Data Integration for Archaeological Investigations: First Results from the Greek City of Gela (Sicily, Italy). Remote Sensing, 17(21), 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213561