Building Outline Extraction via Topology-Aware Loop Parsing and Parallel Constraint from Airborne LiDAR

Highlights

- Boundary point extraction is formulated as a topology-aware loop searching and parsing problem, enabling automatic identification of erroneous boundary points.

- A dominant direction detection method based on angle normalization, merging, and perpendicular pairing is proposed, and building outlines are regularized under the parallel constraint according to the unit length residual metric.

- We propose a robust and accurate solution for boundary point extraction, dominant direction detection, and outline regularization.

- The proposed method can provide accurate and regularized building outlines for building 3D reconstruction and related applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Boundary Point Extraction

2.1.1. Image-Based Method

2.1.2. Triangulation-Based Method

2.1.3. Feature-Based Method

2.1.4. Alpha Shapes Method

2.1.5. Learning-Based Method

2.2. Outline Regularization

2.2.1. Origin Point Selection-Based Method

2.2.2. Dominant Direction-Based Method

2.2.3. Optimization-Based Method

3. Methodology

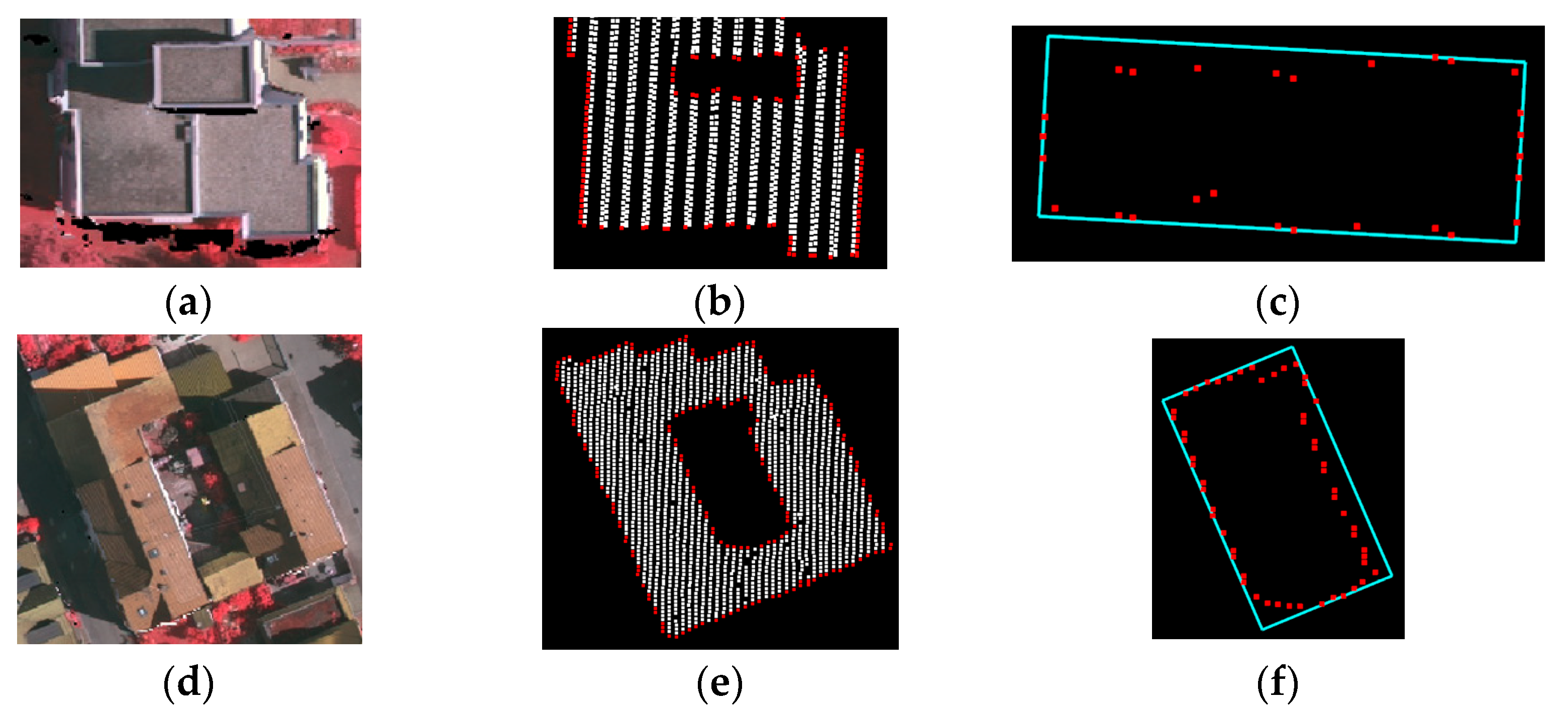

3.1. Boundary Point Extraction

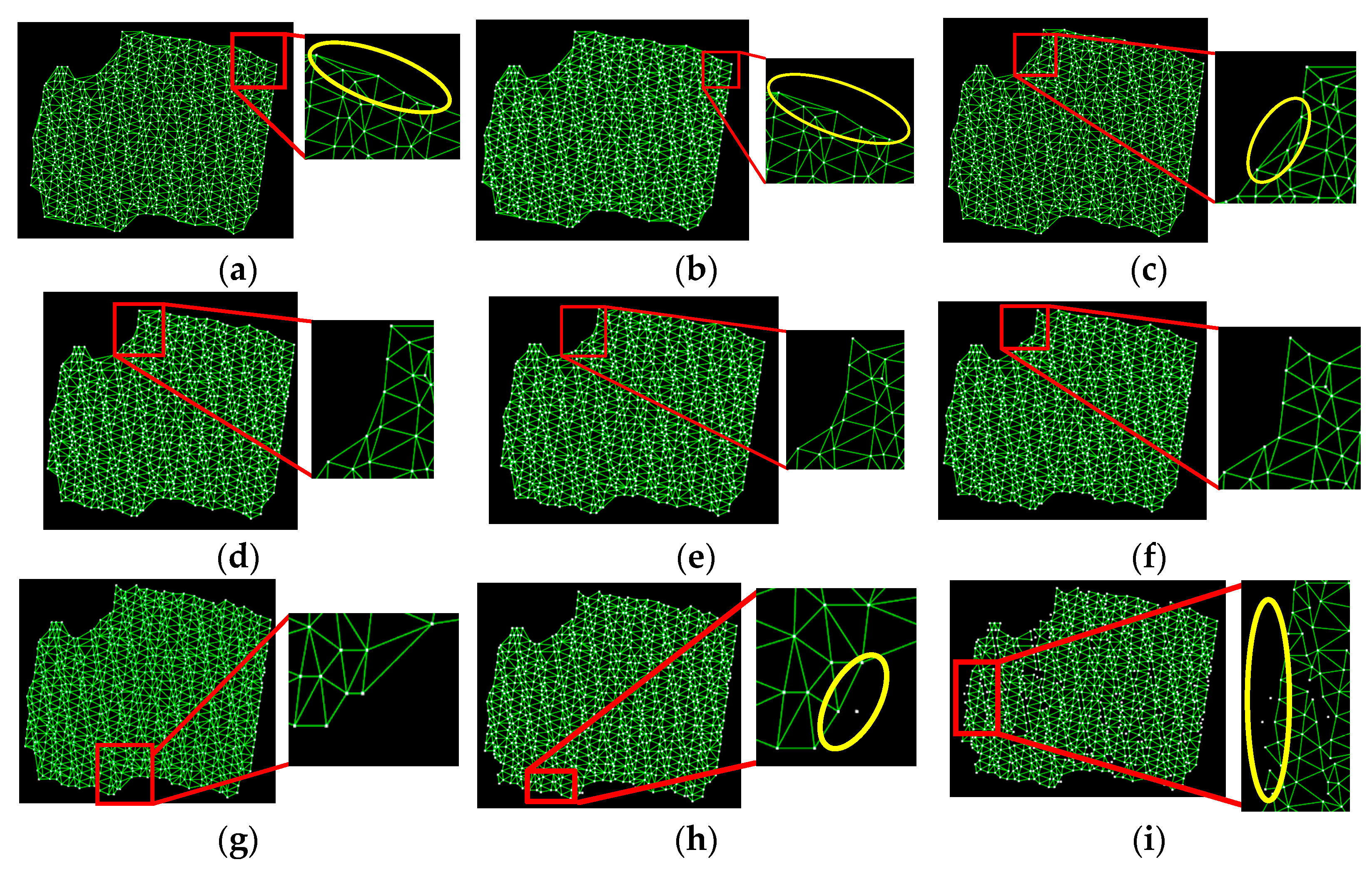

3.1.1. Constrained Delaunay Triangulation (DT)

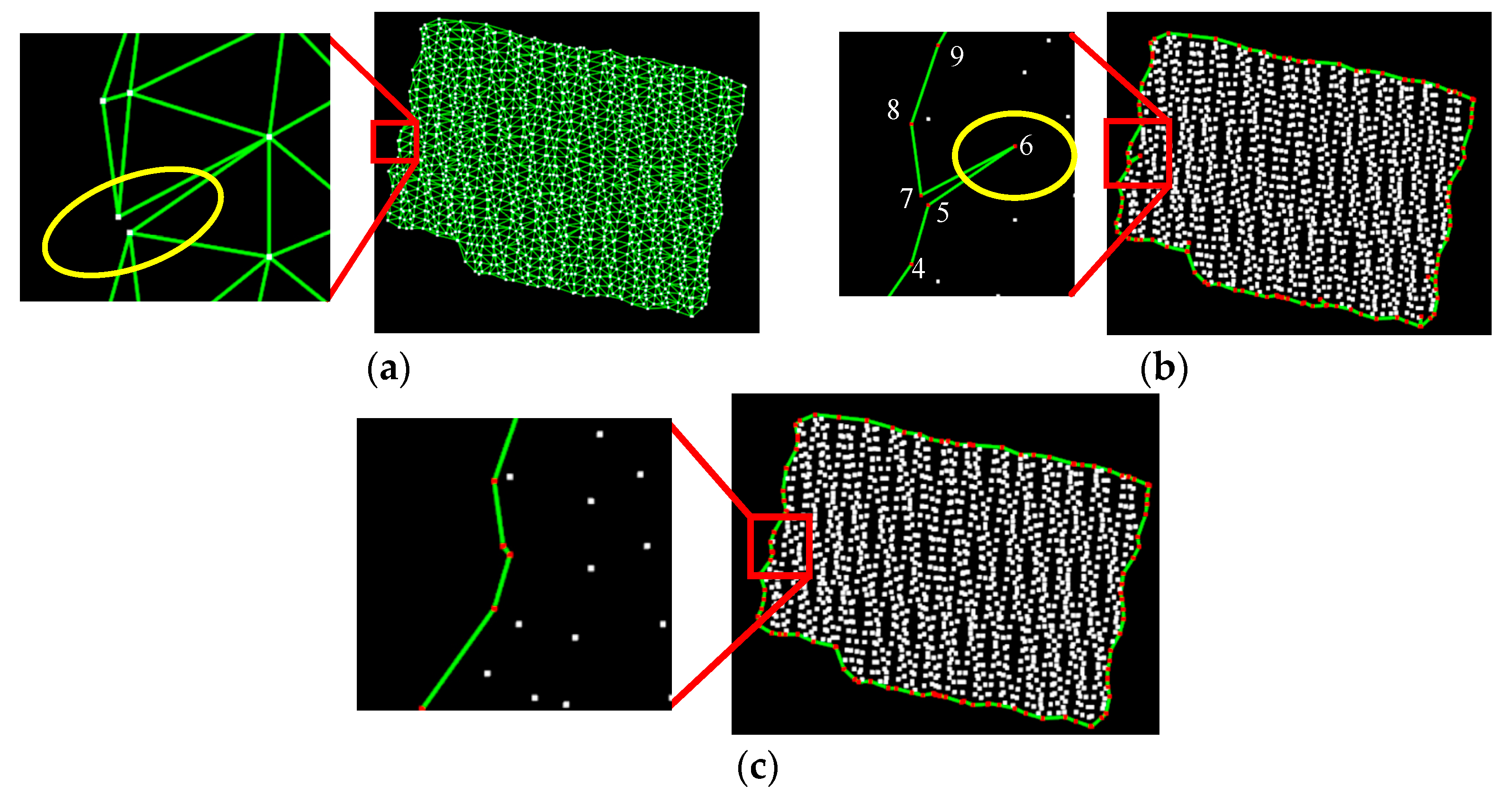

3.1.2. Topology-Aware Loop Searching

| Algorithm 1: Loop extraction |

| Notations: Graph G = (V, E): An undirected graph with a set of vertices V and a set of edges E. List C: A list of closed loops in graph G. Inputs: Graph G. Output: List C. Initialization: Create an empty list C to store the searched closed loops. For each vertex v∈V in the graph G, set its status to “Unvisited”. Begin: for each vertex v in G if v is “Unvisited” Initialize an empty stack S. Initialize an empty path list P to record the current path. Mark v as “Visiting” and push it onto the stack S. Add v to the path list P. end if while S is not empty: Pop a vertex u from the top of S for each adjacent vertex w of u if w is “Visiting” Record the sub-path SP from w to u in P. Get the index min_index of the vertex with the minimum x in SP. Get the sorted SP’ = SP[min_index: ] + SP[ : min_index]. Calculate area A(SP’) and geometric center GC(SP’) of SP’. Set IsDuplicate = true. for each loop in C if A(SP’) ≠ A(loop) or GC(SP’) ≠ GC(loop) IsDuplicate = false. break. else if vertices(SP’) ≠ vertices(loop) IsDuplicate = false. break. end if end for if IsDuplicate = false Add SP’ to C as a closed loop. end if else if w is “Unvisited”: Mark w as “Visiting” and push it onto S. Add w to P. end if end for Mark u as “Visited”. Remove u from the path list. end while end for Termination: The algorithm terminates when all vertices are marked as “Visited”. |

3.1.3. Semantic Boundary Point Extraction

3.2. Outline Regularization

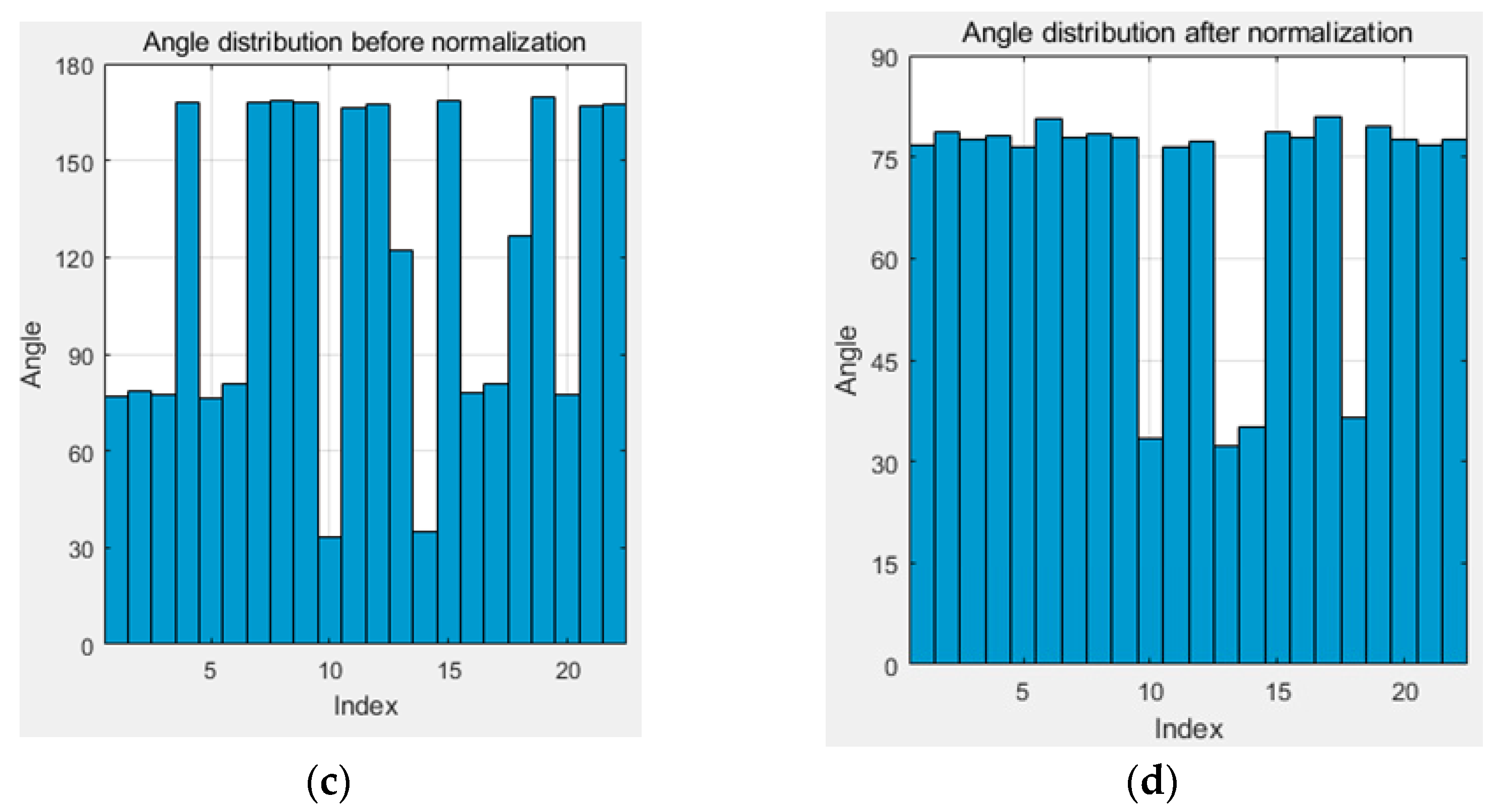

3.2.1. Dominant Direction and Line Segment Extraction

3.2.2. Parallel Constraint-Based Outline Regularization

4. Experiment and Analysis

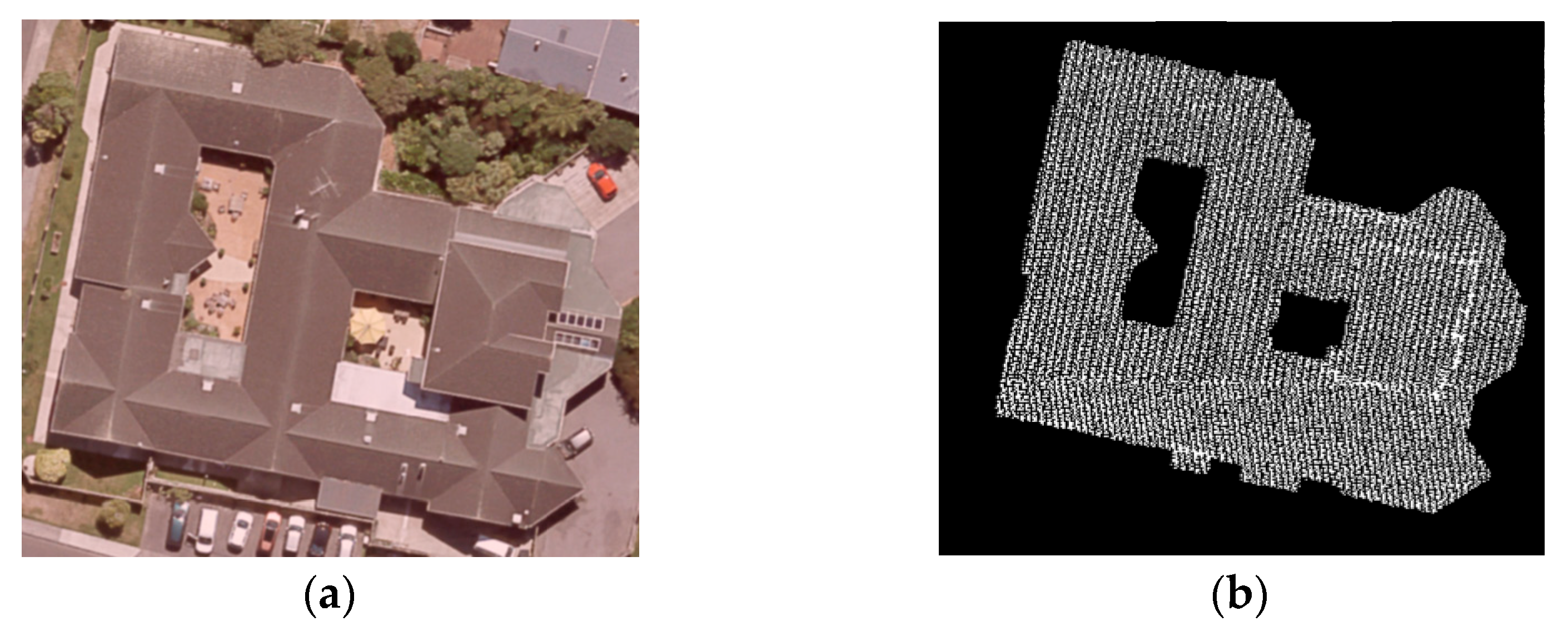

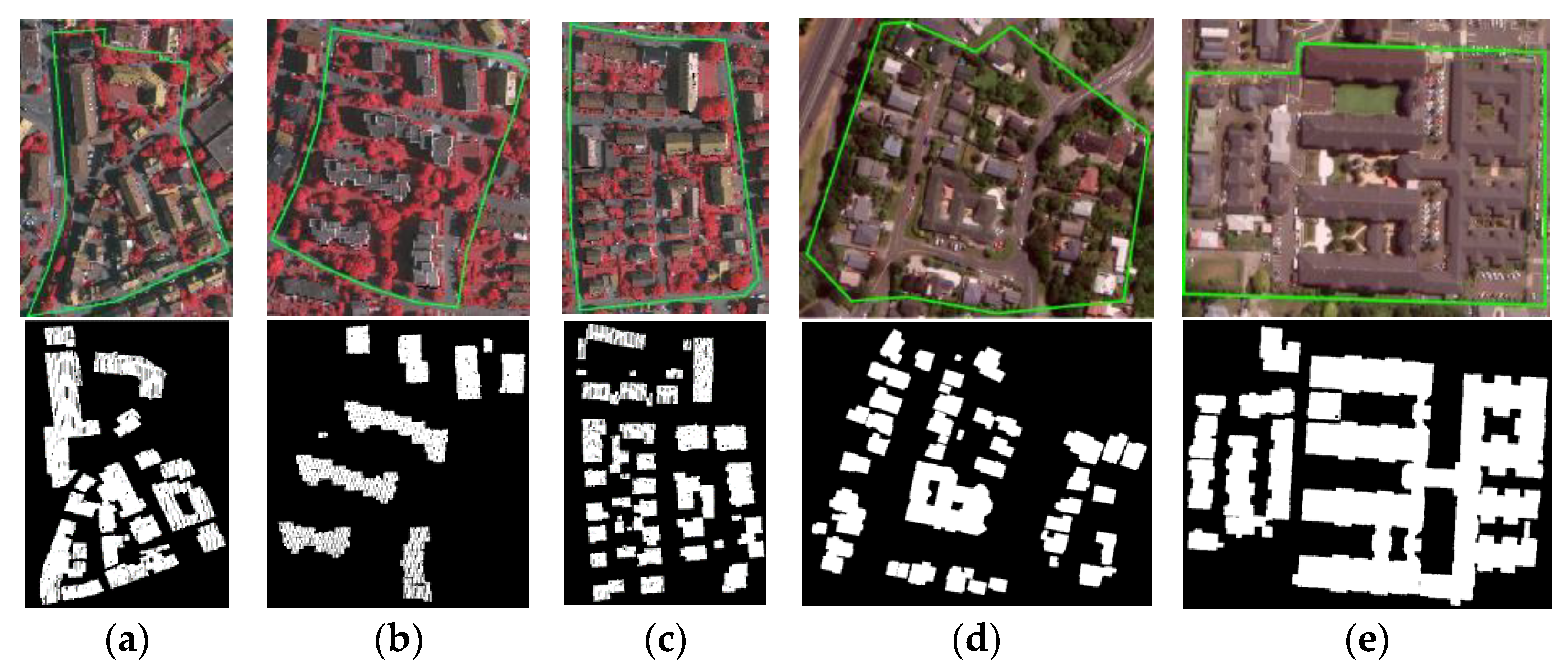

4.1. Data Description

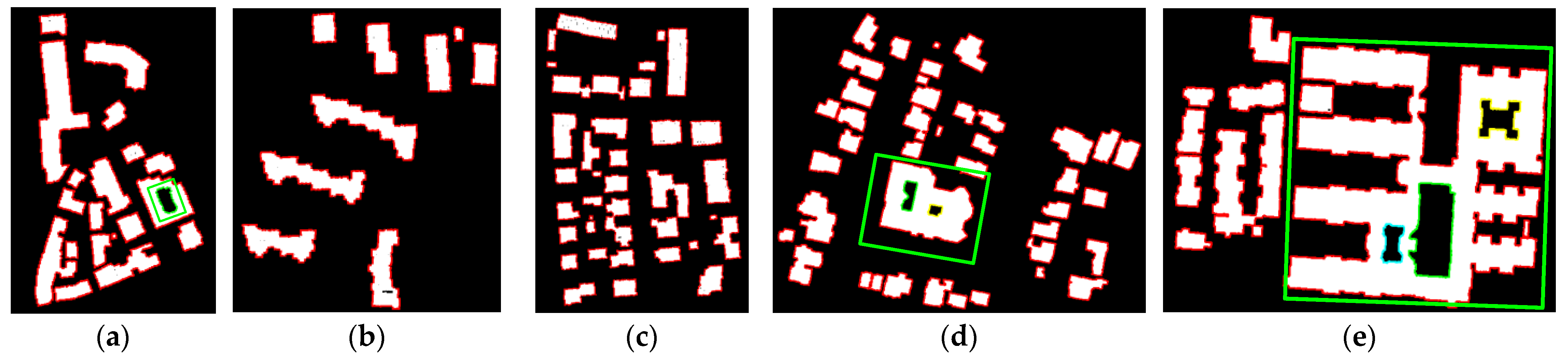

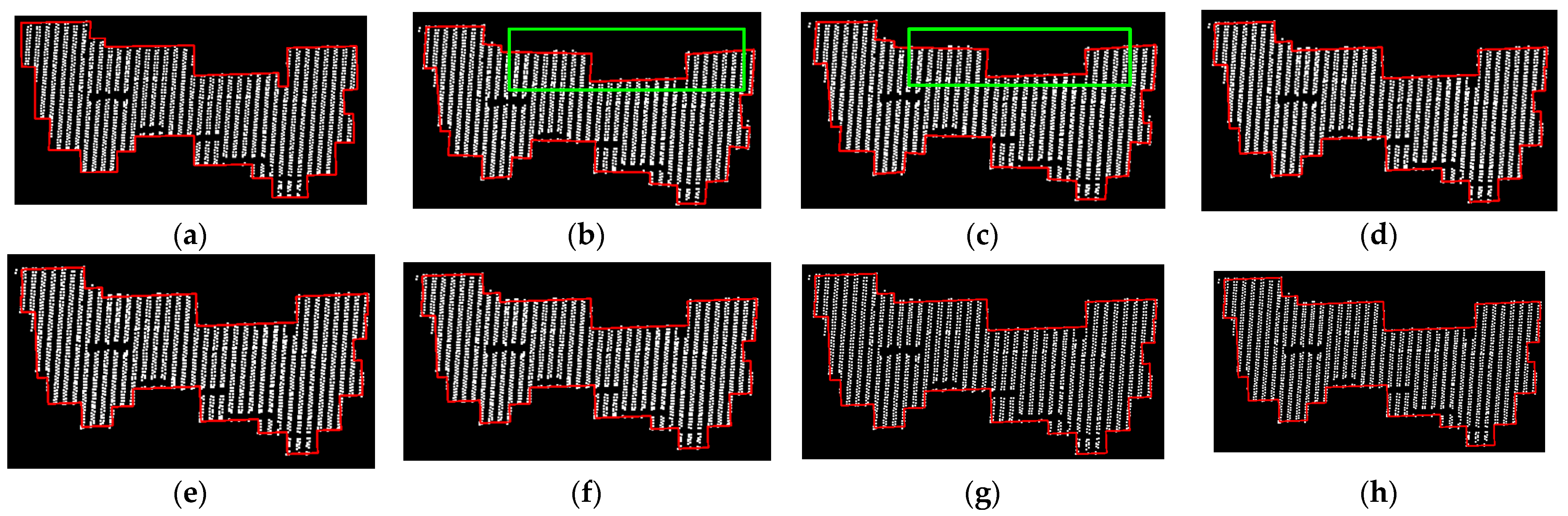

4.2. Boundary Point Extraction

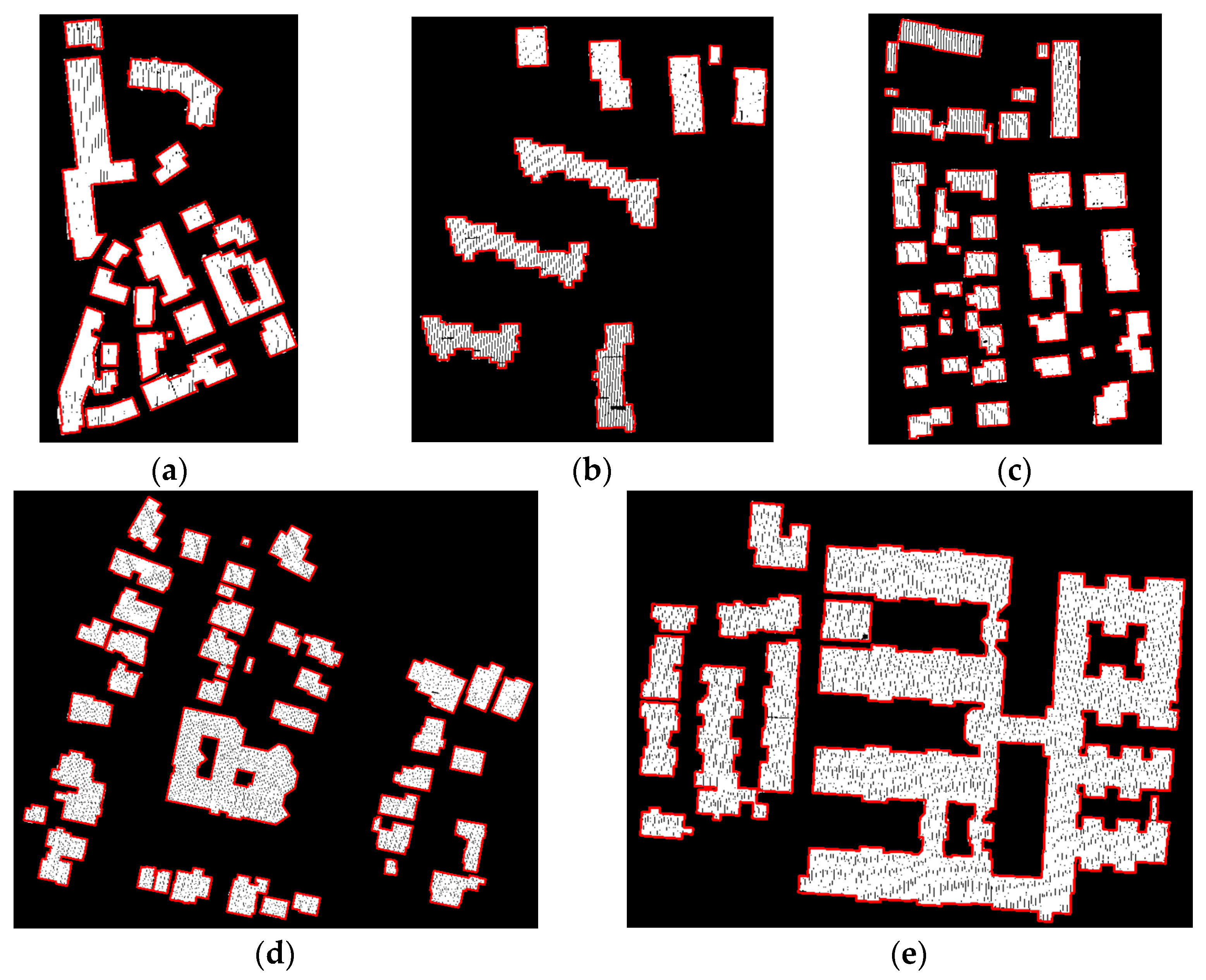

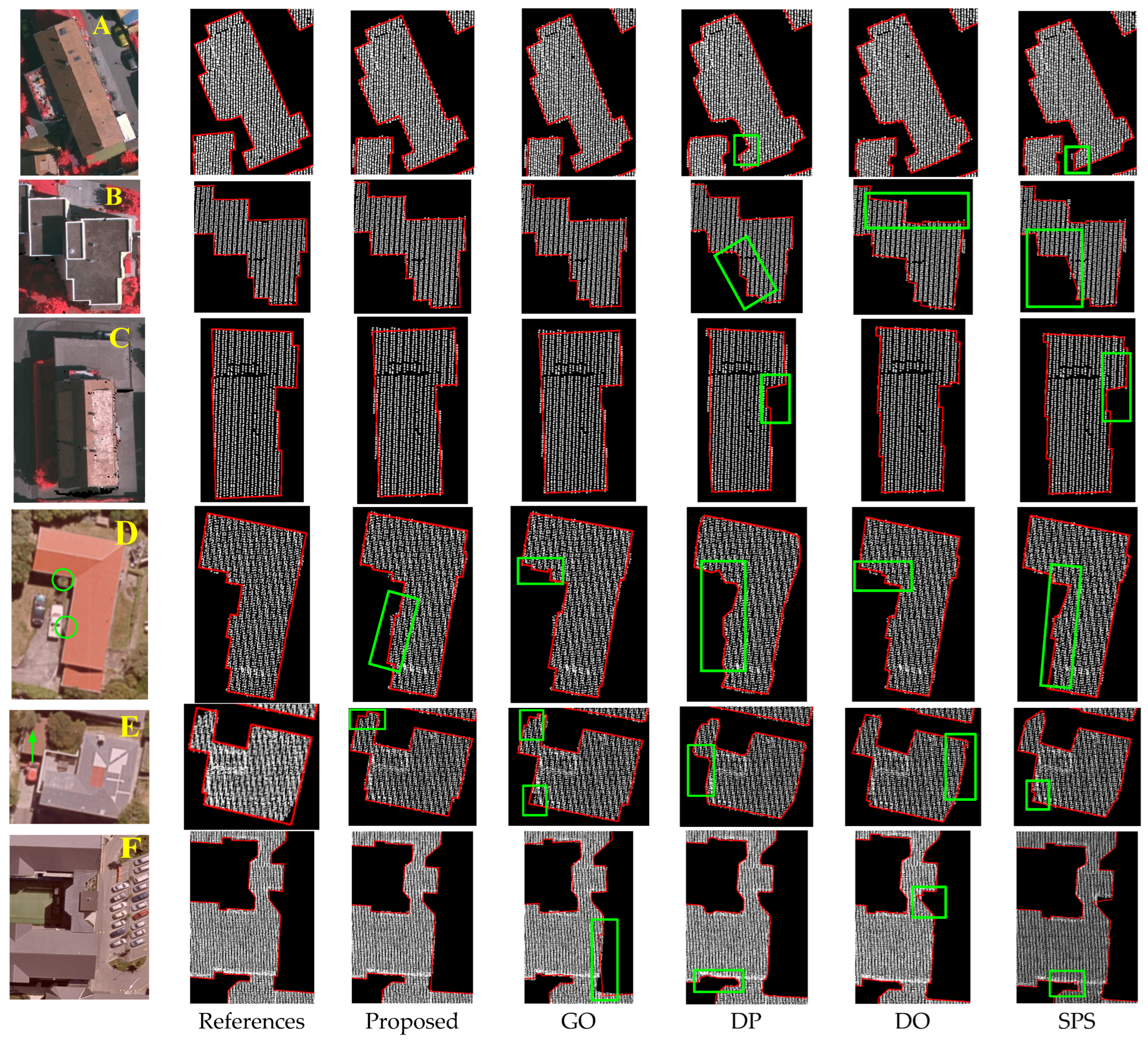

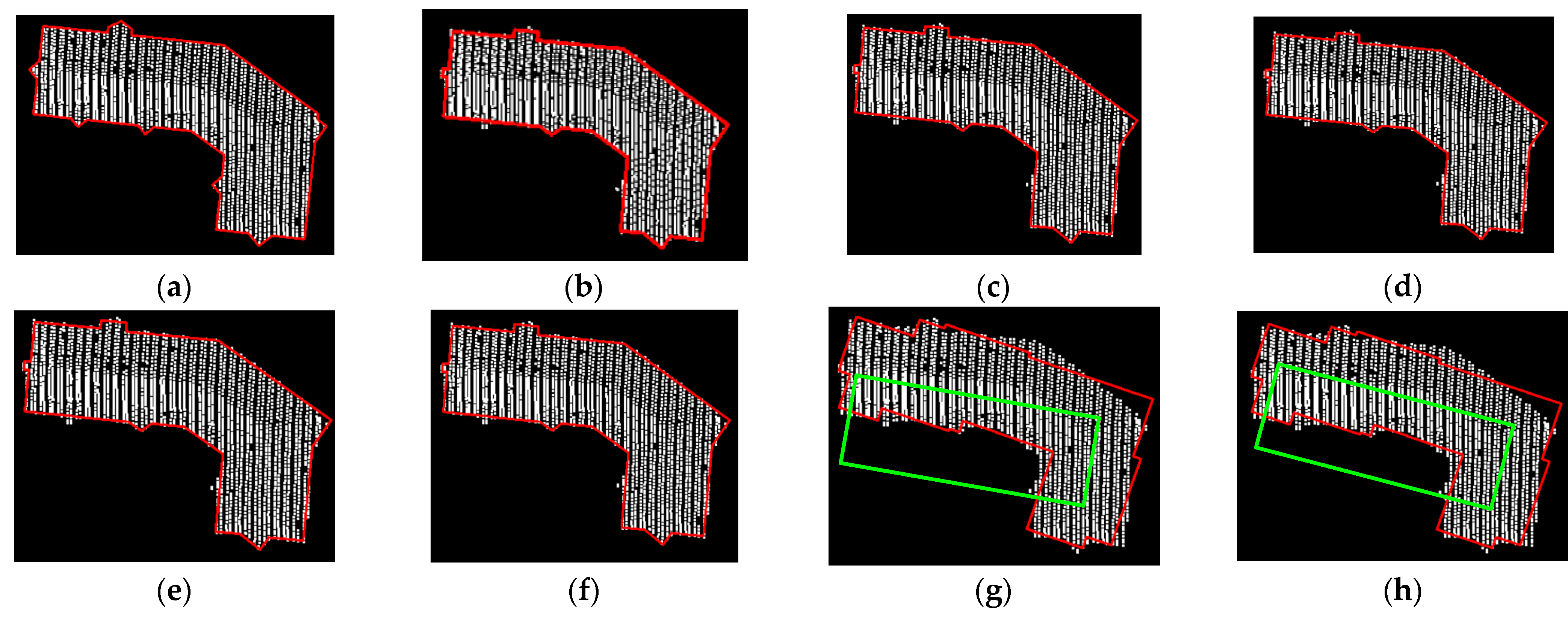

4.3. Outline Extraction

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of SF0

5.2. Discussion of

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, J.; Stoter, J.; Peters, R.; Nan, L. City3D: Large-scale building reconstruction from airborne LiDAR point clouds. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, T.; Weedon, Z.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Corchado, T.; Mehmood, R. Algorithmic urban planning for smart and sustainable development: Systematic review of the literature. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 94, 104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, C.; Aziz, N.; Kamaruzzaman, S. BIM–GIS integrated utilization in urban disaster management: The contributions, challenges, and future directions. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J. Semantic extraction of roof contour lines from airborne LiDAR building point clouds based on multidirectional equal-width banding. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 16316–16328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, R.; Peethambaran, J.; Mathiopoulos, P.; Xie, L.; Yun, T. A novel framework for 2.5-D building contouring from large-scale residential scenes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4121–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Chen, Z.; Tao, R.; Li, J.; Hao, Y. Boundary recognition of ship planar components from point clouds based on trimmed Delaunay triangulation. Comput. Aided Des. Appl. 2025, 178, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. Canny edge detection enhancement by scale multiplication. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 27, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remya, A.; Gopalan, S. Comparative analysis of eight direction Sobel edge detection algorithm for brain tumor MRI images. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 201, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Mittal, A. A survey on various edge detector techniques. Procedia Technol. 2012, 4, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, J.; Shi, G.; Meng, J. Grid partition variable step alpha shapes algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9919003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, F. Morphology-based scattered point cloud contour extraction. J. TongJi Univ. 2014, 42, 1738–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegl, L.; Tiller, W. Algorithm for finding all k nearest neighbors. Comput. Aided Des. 2002, 34, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrangjeb, M. Using point cloud data to identify, trace, and regularize the outlines of buildings. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, R.; Feng, C.; Zhou, X. A novel type of boundary extraction method and its statistical improvement for unorganized point clouds based on concurrent Delaunay triangular meshes. Sensors 2023, 23, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zang, D.; Yu, J.; Xie, X. Extraction of building roof contours from airborne LiDAR point clouds based on multidirectional bands. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Jin, T.; Hua, X.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Jiang, Y.; Hong, Q. UAV building point cloud contour extraction based on the feature recognition of adjacent points distribution. Measurement 2024, 230, 114519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Lin, X.; Ning, X.; Zhang, J. Edge detection and feature line tracing in 3D-point clouds by analyzing geometric properties of neighborhoods. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Z. Point cloud adaptive simplification of feature extraction. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2017, 25, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Salvaggio, C. Aerial 3D building detection and modeling from airborne LiDAR point clouds. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J. Building outer boundary extraction from ALS point clouds using neighborhood point direction distribution. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2021, 29, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D.; Seidel, R. On the shape of a set of points in the plane. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Cheng, L. Extraction of building contour from airborne LiDAR point cloud using variable radius alpha shapes method. J. Image Graph. 2021, 26, 0910–0923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Xu, H.; Yang, Z. Novel algorithm for fast extracting edges from massive point clouds. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2010, 46, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ma, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, L.; Xiang, S.; Chen, D.; Miao, Q. Building outline extraction using adaptive tracing alpha shapes and contextual topological optimization from airborne LiDAR. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Galo, M.; Carrilho, A. Extraction of building roof boundaries from LiDAR data using an adaptive alpha-shape algorithm. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Liang, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Yin, X.; Jia, H.; Liu, Y. Indoor 3D wireframe construction from incomplete point clouds based on Gestalt rules. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, D.; Gao, G.; Liu, R. Extraction of building contour from point clouds using dual threshold alpha shapes algorithm. J. Yangte River Sci. Res. Inst. 2016, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Pessoa, G.; Carrilho, A.; Galo, M. Automatic building boundary extraction from airborne LiDAR data robust to density variation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 6500305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, X.; Fu, C.; Cohen-Or, D.; Heng, P. EC-Net: An edge-aware point set consolidation network. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazazian, D.; Parés, M. EDC-Net: Edge detection capsule network for 3D point clouds. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, T.; Peng, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Large-scale point cloud contour extraction via 3-D-guided multiconditional residual generative adversarial network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, T.; Wegner, J.; Schindler, K. Joint classification and contour extraction of large 3D point clouds. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 130, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, S.; Wang, R. Efficient roof vertex clustering for wireframe simplification based on the extended multiclass twin support vector machine. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6501405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehri, S.; Hooshangi, N.; Mahdizadeh, N. A novel context-aware Douglas–Peucker (CADP) trajectory compression method. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2025, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, N.; Wu, H.; Yang, X. Adjustment model of boundary extraction for urban complicated building based on LiDAR data. J. Tongji Univ. 2012, 40, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Yu, K. Hybrid line simplification for cartographic generalization. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2011, 32, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangayyan, R.; Guliato, D.; Carvalho, J.; Santiago, S. Polygonal approximation of contours based on the turning angle function. J. Electron. Imaging 2008, 17, 023016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiu, F.; Shi, F.; Tang, Y. A recursive hull and signal-based building footprint generation from airborne LiDAR data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, A.; Shan, J. Building boundary tracing and regularization from airborne LiDAR point clouds. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2007, 73, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, R. Extracting buildings from and regularizing boundaries in airborne lidar data using connected operators. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 889–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, E.; Habib, A. Automatic representation and reconstruction of DBM from LiDAR data using recursive minimum bounding rectangle. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 93, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Jin, G.; Xia, Y. An improved minimum bounding rectangle algorithm for regularized building boundary extraction from aerial LiDAR point clouds with partial occlusions. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, H.; Wu, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, R. Hierarchical regularization of building boundaries in noisy aerial laser scanning and photogrammetric point clouds. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullis, C. A framework for automatic modeling from point cloud data. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 2563–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, B.; Kada, M.; Wichmann, A. Automatic extraction and regularization of building outlines from airborne LiDAR point clouds. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 41, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Chen, D.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Geometric primitives in LiDAR point clouds: A review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewchuk, J. Delaunay refinement algorithms for triangular mesh generation. Comput. Geom. 2002, 22, 21–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrate, J.; Palau, J.; Huerta, A. Numerical representation of the quality measures of triangles and triangular meshes. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2003, 19, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Waslander, S.; Liu, X. An end-to-end shape modeling framework for vectorized building outline generation from aerial images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 170, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shapiro, L. Closing the loop for edge detection and object proposals. In Proceedings of the Conference on Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; pp. 4204–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wang, M.; Cai, Y.; Lu, S. Extracting closed object contour in the image: Remove, connect and fit. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2019, 22, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenburg, J.; Nelson, P. Improving the efficiency of depth-first search by cycle elimination. Inf. Process. Lett. 1993, 45, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M.; Tenpierik, M.; Dobbelsteen, A. Environmental impact of courtyards—A review and comparison of residential courtyard buildings in different climates. J. Green Build. 2012, 7, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, B. A review on courtyard design criteria in different climatic zones. Afr. Res. Rev. 2016, 10, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuero, A.; González, G. Fitting straight lines with replicated observations by linear regression. III. Weighting data. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2007, 37, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Neumann, U. Complete residential urban area reconstruction from dense aerial LiDAR point clouds. Graph. Models. 2013, 75, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yan, J.; Chen, S. Automatic construction of building footprints from airborne LIDAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wu, H.; Yue, H.; Jia, S.; Li, J.; Liu, C. Automatic extraction and reconstruction of a 3D wireframe of an indoor scene from semantic point clouds. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 3239–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Deng, L.; Peng, G. Algorithms study of building boundary extraction and normalization based on LiDAR data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 12, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrangjeb, M.; Fraser, C. An automatic and threshold-free performance evaluation system for building extraction techniques from airborne LiDAR data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 4184–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. J. Mach. Learn. Technol. 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baswana, S.; Chaudhury, S.; Choudhary, K.; Khan, S. Dynamic DFS in undirected graphs: Breaking the O(m) barrier. SIAM J. Comput. 2019, 48, 1335–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawarneh, A.; Foschini, L.; Bellavista, P. Polygon simplification for the efficient approximate analytics of georeferenced big data. Sensors 2023, 23, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calasan, M.; Aleem, S.; Zobaa, A. On the root mean square error (RMSE) calculation for parameter estimation of photovoltaic models: A novel exact analytical solution based on Lambert W function. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 210, 112716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaningrum, E.; Peters, R.; Lindenbergh, R. Building outline extraction from ALS point clouds using medial axis transform descriptors. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 106, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avbelj, J.; Müller, R.; Bamler, R. A metric for polygon comparison and building extraction evaluation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 12, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, E.; Awrangjeb, M. A robust performance evaluation metric for extracted building boundaries from remote sensing data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 4030–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrangjeb, M.; Lu, G.; Fraser, C. Automatic building extraction from LiDAR data covering complex urban scenes. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, 40, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Fan, H.; Lobaccaro, G. Automatic building outline extraction from ALS point cloud data using generative adversarial network. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 15964–15981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vaihingen | New Zealand | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area 1 | Area 2 | Area 3 | Average | Area 4 | Area 5 | Average | |

| Number of points | 21,775 | 17,370 | 26,892 | 22,012 | 139,566 | 221,279 | 180,422 |

| CP% | 98.26 | 93.11 | 94.29 | 95.22 | 94.38 | 94.41 | 94.40 |

| CR% | 99.75 | 99.65 | 97.88 | 99.09 | 97.95 | 98.52 | 98.24 |

| Q% | 98.01 | 92.80 | 92.40 | 94.40 | 92.56 | 93.09 | 92.83 |

| F1% | 99.00 | 96.27 | 96.05 | 97.11 | 96.13 | 96.42 | 96.28 |

| T1(s) | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 2.74 | 7.51 | 5.13 |

| T2(s) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.14 | 2.17 | 1.65 |

| T(s) | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 3.88 | 9.68 | 6.78 |

| RAM (MB) | 2.98 | 2.78 | 3.33 | 3.03 | 19.66 | 31.68 | 25.67 |

| Vaihingen | New Zealand | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP% | CR% | Q% | F1% | T(s) | CP% | CR% | Q% | F1% | T(s) | |

| Proposed | 95.22 | 99.09 | 94.40 | 97.11 | 0.44 | 94.40 | 98.24 | 92.83 | 96.28 | 6.78 |

| TB | 74.53 | 96.70 | 72.68 | 84.06 | 0.38 | 84.73 | 98.01 | 83.30 | 90.86 | 6.01 |

| AS | 97.23 | 94.35 | 91.84 | 95.74 | 1.47 | 86.37 | 98.72 | 85.41 | 92.13 | 21.21 |

| ATAS | 97.69 | 93.88 | 91.78 | 95.71 | 0.68 | 84.73 | 98.01 | 83.30 | 90.89 | 4.33 |

| MA | 96.48 | 92.89 | 89.78 | 94.61 | 0.22 | 94.24 | 92.78 | 87.79 | 93.50 | 1.93 |

| Dataset | RMSE | PoLiS | RCC | T (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaihingen | Area 1 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.89 |

| Area 2 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.58 | |

| Area 3 | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 1.41 | |

| New Zealand | Area 4 | 0.78 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 3.24 |

| Area 5 | 0.94 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 3.34 | |

| Methods | Vaihingen | New Zealand | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | PoLiS | RCC | T(s) | RMSE | PoLiS | RCC | T (s) | |

| Proposed | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 3.29 |

| GO | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 2.64 |

| DO | 1.17 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 1.02 |

| DP | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.86 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| SPS | 1.13 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 0.97 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 1.09 |

| [68] | 0.87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [69] | - | 0.43 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, K.; Ma, H.; Li, L.; Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Cai, Z. Building Outline Extraction via Topology-Aware Loop Parsing and Parallel Constraint from Airborne LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203498

Liu K, Ma H, Li L, Huang S, Zhang L, Liang X, Cai Z. Building Outline Extraction via Topology-Aware Loop Parsing and Parallel Constraint from Airborne LiDAR. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(20):3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203498

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ke, Hongchao Ma, Li Li, Shixin Huang, Liang Zhang, Xiaoli Liang, and Zhan Cai. 2025. "Building Outline Extraction via Topology-Aware Loop Parsing and Parallel Constraint from Airborne LiDAR" Remote Sensing 17, no. 20: 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203498

APA StyleLiu, K., Ma, H., Li, L., Huang, S., Zhang, L., Liang, X., & Cai, Z. (2025). Building Outline Extraction via Topology-Aware Loop Parsing and Parallel Constraint from Airborne LiDAR. Remote Sensing, 17(20), 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203498