Analysis of Maize Sowing Periods and Cycle Phases Using Sentinel 1&2 Data Synergy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Satellite Data

2.2.1. Sentinel-1

2.2.2. Normalized SAR-Derived Index

2.2.3. Sentinel-2

2.2.4. Soil Moisture Satellite Product

2.3. Maize Fields Characterization

2.4. Identification of Crop Emergence and Sowing Periods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Potential Rainfed Fields

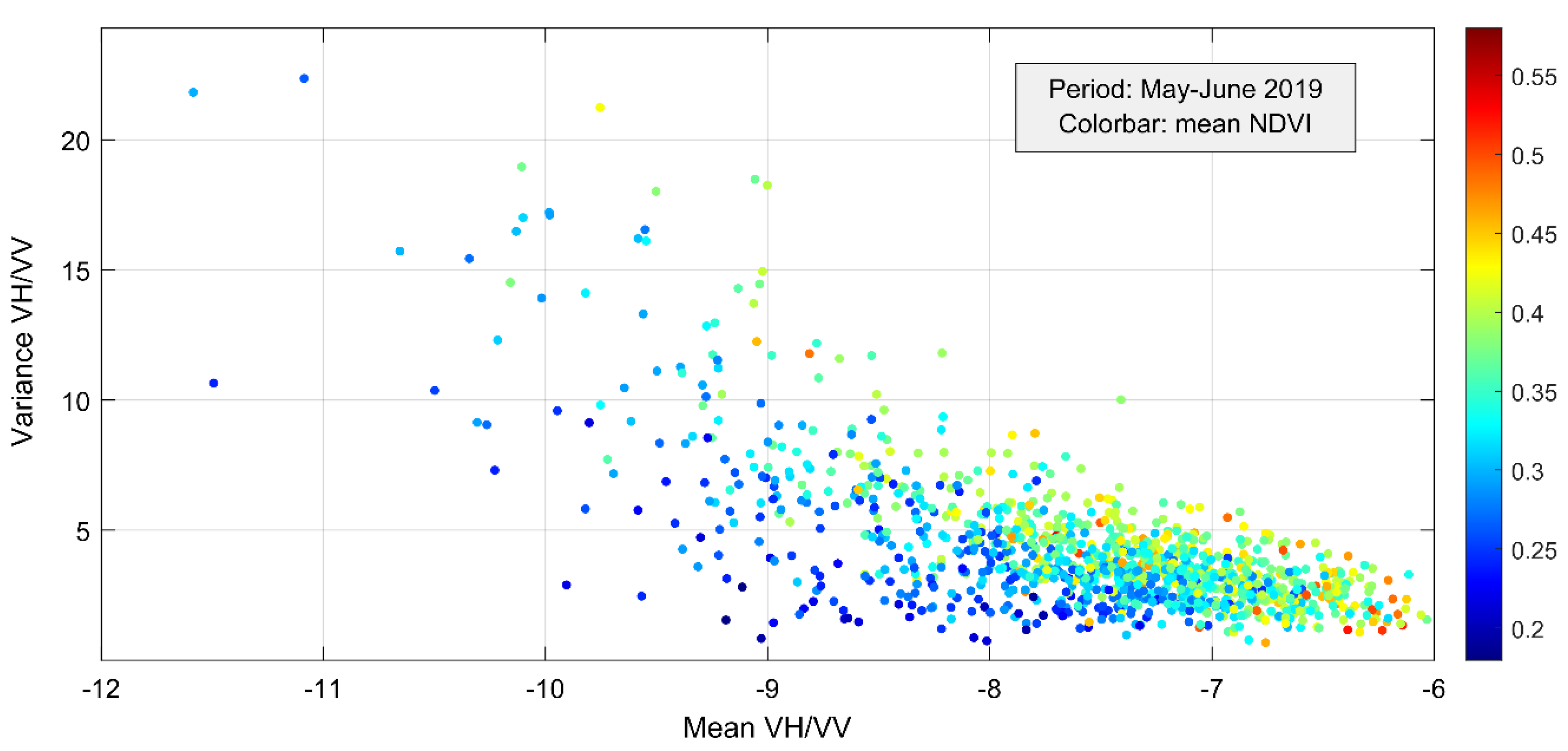

3.2. Growing Phases

3.3. Emerging of Plants and Sowing Periods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Question 1. In which period of the year is maize usually sown?

- 1.

- F1. Usually, maize is sown twice per year. The first sowing is between the 10th and 30th of April; the second sowing occurs between the end of May and the first half of June. The choice of the sowing date depends mainly on soil moisture and weather conditions: soil temperature must be equal or above 13 °C, and there must be low risk of late frost.

- 2.

- F2. Maize is usually sown during the second half of April, or between 15 May and the first week of June. The period depends on the final product to be obtained (chopped maize or dry grain). The choice of sowing day is mainly driven by meteorological factors and soil temperature.

- 3.

- F3. According to the soil moisture and weather conditions, maize is sown from the beginning of April. The provider of seeds insures farmers against late frost: if the plant growth is blocked by late frosts in April, a new sowing can be done for free.

- 4.

- F4. If the soil moisture and weather conditions are optimal, the sowing period starts during the second half of April.

- 5.

- F5. Two growing seasons are usually planned. The first starts in April (usually during the last two weeks) and the second starts in late May.

- Question 2. In which period of the year is maize usually harvested?

- 1.

- F1. Usually between September and October (e.g., October in 2021). The harvesting period depends on the intended use of maize, for which grains must reach optimum levels of moisture. A moisture of 30%–35% is required for chopped maize; a moisture of 25% is required for dry grain at the harvesting date (after that, grains are left to dry up to 12%).

- 2.

- F2. Chopped maize is usually harvested around 15 September. Dry grain maize is usually harvested around the middle of October.

- 3.

- F3. The most crucial factor is the optimum moisture of maize grains. Usually, the maize growing season is 120–130 days long.

- 4.

- F4. From the second half of September to late October, according to the required moisture of maize seeds and on weather conditions.

- 5.

- F5. Chopped maize is usually harvested at the beginning of September. The harvesting period for dry grain maize is usually October.

- Question 3. How are maize fields used during rest periods? (e.g., fallow lands, other crops)

- 1.

- F1. Fields are usually cultivated with fodder grasses or winter wheat from autumn to spring. Typically, the rotation scheme for these months is: 1 year of winter wheat and then 3 consecutive years of fodder grasses. Maize is not cultivated in summer after winter wheat, because wheat is harvested in July.

- 2.

- F2. The crop rotation involves fodder grasses and barley (all cultivated in summer). The scheme is 5–6 years of fodder grasses, 1–2 years of maize, 1–2 years of barley.

- 3.

- F3. Maize fields are usually lying fallow during winter.

- 4.

- F4. Croplands are located at high elevations, close to the Alps. Nothing is cultivated during winter.

- 5.

- F5. Crop rotation is a summer practice. During winter, croplands are cultivated with fodder grasses.

- Question 4. Approximately, how long do the plants take to reach the maximum stage of growth from seed?

- 1.

- F1. The maximum growing stage is reached by maize in the second half of July for those years when seeds are sown around 15 April.

- 2.

- F2. Between June 20th and the first week of July, according on the date of sowing.

- 3.

- F3. The maximum stage of growth is usually reached in the first two weeks of July.

- 4.

- F4. The maximum stage of growth is usually reached in the first two weeks of July.

- 5.

- F5. According to the maize variety, the maximum growing phase is reached in mid-July.

References

- Pasquel, D.; Roux, S.; Richetti, J.; Cammarano, D.; Tisseyre, B.; Taylor, J.A. A review of methods to evaluate crop model performance at multiple and changing spatial scales. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1489–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, M.; Tamea, S.; Claps, P. Climate-driven trends in agricultural water requirement: An ERA5-based assessment at daily scale over 50 years. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Elliot, J.; Deryng, D.; Ruane, A.C. Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 11, 3268–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, P. The future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, D.; Guan, K.; Jain, M. Estimating sowing dates from satellite data over the US Midwest: A comparison of multiple sensors and metrics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 211, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, S.; Good, D.; Newton, J. Early Planting and 2015 Corn Yield Prospects: How Much of an Increase? Farmdoc Dly. 2015, 5, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Monasterio, J.I.; Dhillon, J.; Fisher, S. RA Date of sowing effects on grain yield and yield components of irrigated spring wheat cultivars and relationships with radiation and temperature in Ludhiana, India. Field Crop. Res. 1994, 37, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, S.; Soussana, J.; Tubiello, F. Adapting agriculture to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19691–19696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dharmarathna, W.; Herath, S.; Weerakoon, S. Changing the planting date as a climate change adaptation strategy for rice production in Kurunegala district, Sri Lanka. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, V.; Eitzinger, J.; Cajic, J.; Oberforster, M. Potential impact of climate change on selected agricultural crops in north-eastern Austria. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2002, 8, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, B.; Cossar, R. Castor yield in response to planting date at four locations in the south-central United States. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 29, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Siderius, C.; Hellegers, P. Limitations to adjusting growing periods in different agroecological zones of Pakistan. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliander, A.; Reichle, R.; Crow, W.; Cosh, M.H.; Chen, F.; Chan, S.; Das, N.N.; Bindlish, R.; Chaubell, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Validation of soil moisture data products from the NASA SMAP mission. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 15, 364–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Jacob, F.; Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaadi, N.; Jarlan, L.; Ezzahar, L.; Zribi, M.; Zribi, M.; Khabba, S.; Bouras, E.; Bousbih, S.; Frison, P.L. Monitoring of wheat crops using the backscattering coefficient and the interferometric coherence derived from Sentinel-1 in semi-arid areas. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112050. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah, A.; Baghdadi, N.; El Hajj, M.; Darwish, T. Sentinel-1 Data for Winter Wheat Phenology Monitoring and Mapping. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pascale, C.; Dubois, P.; Van Zyl, J.; Engman, T. Measuring soil moisture with imaging radars. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 915–926. [Google Scholar]

- Portmann, F.; Siebert, S.; Döll, P. MIRCA2000—Global monthly irrigated and rainfed crop areas around the year 2000: A new high-resolution data set for agricultural and hydrological modeling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2010, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Gillet, V. Irrigation Water Requirement and Water Withdrawal by Country; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Abrahao, G.; Cohn, A.; Campolo, J.; Thompson, S. A MODIS-based scalable remote sensing method to estimate sowing and harvest dates of soybean crops in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, E.; Ghazaryan, G.; González, J.; Cornish, N.; Dubovyk, O.; Siebert, S. The use of remote sensing to derive maize sowing dates for large-scale crop yield simulations. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.; Sibley, A.; Ortiz-Monasterio, I.J. Extreme heat effects on wheat senescence in India. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousbih, S.; Zribi, M.; Lili-Chabaane, Z.; Baghdadi, N.; El Hajj, M.; Gao, Q.; Mougenot, B. Potential of Sentinel-1 Radar Data for the Assessment of Soil and Cereal Cover Parameters. Sensors 2017, 17, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Copernicus European Programme, Land Service. CORINE Land Cover: CLC_2018 v.2020_20u1. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. GEO-Piemonte: Modello Digitale del Terreno da CTRN 1:10,000 (Passo 10 m)—STORICO. Available online: https://www.geoportale.piemonte.it/geonetwork/srv/ita/catalog.search#/metadata/r_piemon:3ffe6b7b-9abe-4459-8305-e444e8eb197c (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Braca, G.; Bussettini, M.; Lastoria, B.; Mariani, S.; Piva, F. Il bilancio idrologico GIS based a scala nazionale su griglia regolare—BIGBANG: Metodologia e stime. Rapporto sulla disponibilità naturale della risorsa idrica Rapp. ISPRA 2021, 339, 1–181. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Agricultura. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/agricoltura?dati (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- ISTAT. 6° Censimento Agricoltura 2010: Data Warehouse. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. Bonifica e Irrigazione (SIBI). Available online: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/temi/agricoltura/agroambiente-meteo-suoli/bonifica-irrigazione-sibi (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. Sistema Informativo Risorse Idriche (SIRI). Available online: http://www.regione.piemonte.it/siriw/cartografia/mappa.do;jsessionid=E4D50E350BDDEF87B8B00E2144523402.part212node11 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- ESA Sentinels. Sentinel-1, Level-1 GRD Products. Available online: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/web/sentinel/technical-guides/sentinel-1-sar/products-algorithms/level-1-algorithms/ground-range-detected (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Earth Engine. Sentinel-1 Algorithms, Google 2022. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/guides/sentinel1 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Engman, E. Applications of microwave remote sensing of soil moisture for water resources and agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 35, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, M.; Baghdadi, N.; Holah, N.; Fafin, O.; Guérin, C. Evaluation of a rough soil surface description with ASAR-ENVISAT radar data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 95, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.; Farr, T.; Zyl, J. Estimates of surface roughness derived from synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, A.; Mermoz, S.; Bouvet, A.; Le Toan, T.; Planells, M.; Dejoux, J.F.; Ceschia, E. Understanding the temporal behavior of crops using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2-like data for agricultural applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 199, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.; Deering, D. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement and Retrogradation (Green Wave Effect) of Natural Vegetation; No. NASA-CR-132982; Texas A and M University, College Station. Remote Sensing Center: College Station, TX, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Theia. Value-Adding Products and Algorithms for Land Surfaces. Available online: https://www.theia-land.fr/en/homepage-en/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Ayari, E.; Kassouk, Z.; Lili-Chabaane, Z.; Baghdadi, N.; Bousbih, S.; Zribi, M. Cereal crops soil parameters retrieval using L-band ALOS-2 and C-band Sentinel-1 sensors. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M.; Baghdadi, N.; Zribi, M.; Bazzi, H. Synergic Use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Images for Operational Soil Moisture Mapping at High Spatial Resolution over Agricultural Areas. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- THISME. THeia and Irstea Soil MoisturE Catalog. Available online: https://thisme.cines.teledetection.fr/home (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Le Page, M.; Jarlan, L.; El Hajj, M.; Zribi, M.; Baghdadi, N.; Boone, A. Potential for the Detection of Irrigation Events on Maize Plots Using Sentinel-1 Soil Moisture Products. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Piemonte. GEO-Piemonte: Mosaicatura Catastale di Riferimento Regionale. Available online: https://www.geoportale.piemonte.it/cms/progetti/progetto-mosaicatura-catastale (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. Anagrafe Agricola Unica—Data Warehouse e Open Data. Available online: http://www.sistemapiemonte.it/fedwanau/elenco.jsp (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- El Hajj, M.; Baghdadi, N.; Bazzi, H.; Zribi, M. Penetration analysis of SAR signals in the C and L bands for wheat, maize, and grasslands. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regione Piemonte. Norme Tecniche di Produzione Integrata: Difesa, Diserbo e Pratiche Agronomiche 2018. Available online: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/sites/default/files/media/documenti/2018-11/norme_tecniche_piemonte_2018.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Muth, L.; Diamond, D.; Lelis, J. Uncertainty Analysis of Radar Cross Section Calibration at Etcheron Valley Range; Technical Note (NIST TN) 1534; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2004.

- Swan, J.B.; Schneider, E.C.; Moncrief, J.F.; Paulson, W.H.; Peterson, A.E. Estimating corn growth, yield, and grain moisture from air growing degree days and residue cover. Agron. J. 1987, 79, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, H.; Lauer, J. Plant Physiology: Critical Stages in the Life of a Corn Plant. Technol. Rep. 2004. Available online: http://corn.agronomy.wisc.edu/Management/pdfs/CriticalStages.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Abendroth, L.J.; Elmore, R.W.; Boyer, M.J.; Marlay, S.K. Corn Growth and Development, 1st ed.; Iowa State University, University Extension: Ames, IA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, A.; Maucieri, C.; Bonamano, A.; Borin, M. Short-term climate change effects on maize phenological phases in northeast Italy. Italy J. Agron. 2019, 14, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corn Agronomy. Corn Development. Available online: http://corn.agronomy.wisc.edu/Management/L011.aspx (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Arpa Piemonte. Annali Meteorologici ed Idrologici. Available online: https://www.arpa.piemonte.it/rischinaturali/accesso-ai-dati/annali_meteoidrologici/annali-meteo-idro/annali-meteorologici-ed-idrologici.html (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Schneider, E.C.; Gupta, S.C. Corn emergence as influenced by soil temperature, matric potential, and aggregate size distribution. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO Rome 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 1st ed.; Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.: Belmont, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, R.; Villa, P.; Stroppiana, D.; Crema, A.; Boschetti, M.; Brivio, P.A. Assessing in-season crop classification performance using satellite data: A test case in Northern Italy. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 49, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. IPAD Crop Calendars. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/ogamaps/cropcalendar.aspx (accessed on 2 March 2022).

| Month | Correlation between NDVI and VH/VV | Comparison of NDVI and Soil Moisture (SM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (in ID) | R (out ID) | NDVI (in ID) | NDVI (out ID) | SM (in ID) | SM (out ID) | |

| April | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| May | 0.62 | 0.6 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| June | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| July | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rolle, M.; Tamea, S.; Claps, P.; Ayari, E.; Baghdadi, N.; Zribi, M. Analysis of Maize Sowing Periods and Cycle Phases Using Sentinel 1&2 Data Synergy. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153712

Rolle M, Tamea S, Claps P, Ayari E, Baghdadi N, Zribi M. Analysis of Maize Sowing Periods and Cycle Phases Using Sentinel 1&2 Data Synergy. Remote Sensing. 2022; 14(15):3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153712

Chicago/Turabian StyleRolle, Matteo, Stefania Tamea, Pierluigi Claps, Emna Ayari, Nicolas Baghdadi, and Mehrez Zribi. 2022. "Analysis of Maize Sowing Periods and Cycle Phases Using Sentinel 1&2 Data Synergy" Remote Sensing 14, no. 15: 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153712

APA StyleRolle, M., Tamea, S., Claps, P., Ayari, E., Baghdadi, N., & Zribi, M. (2022). Analysis of Maize Sowing Periods and Cycle Phases Using Sentinel 1&2 Data Synergy. Remote Sensing, 14(15), 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153712