Spatial and Economic Differentiation of Land Use for Organic Farming in the European Union

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

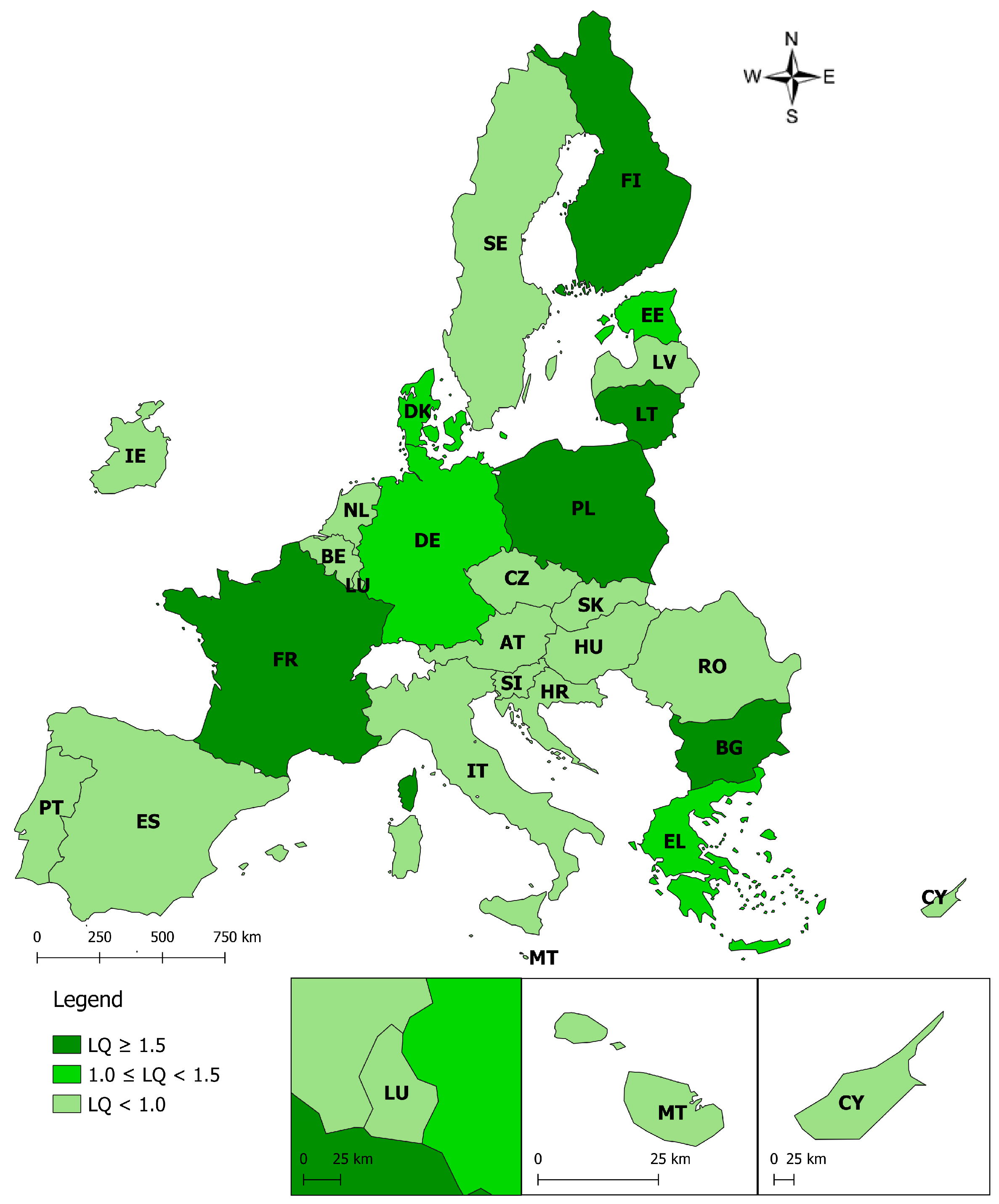

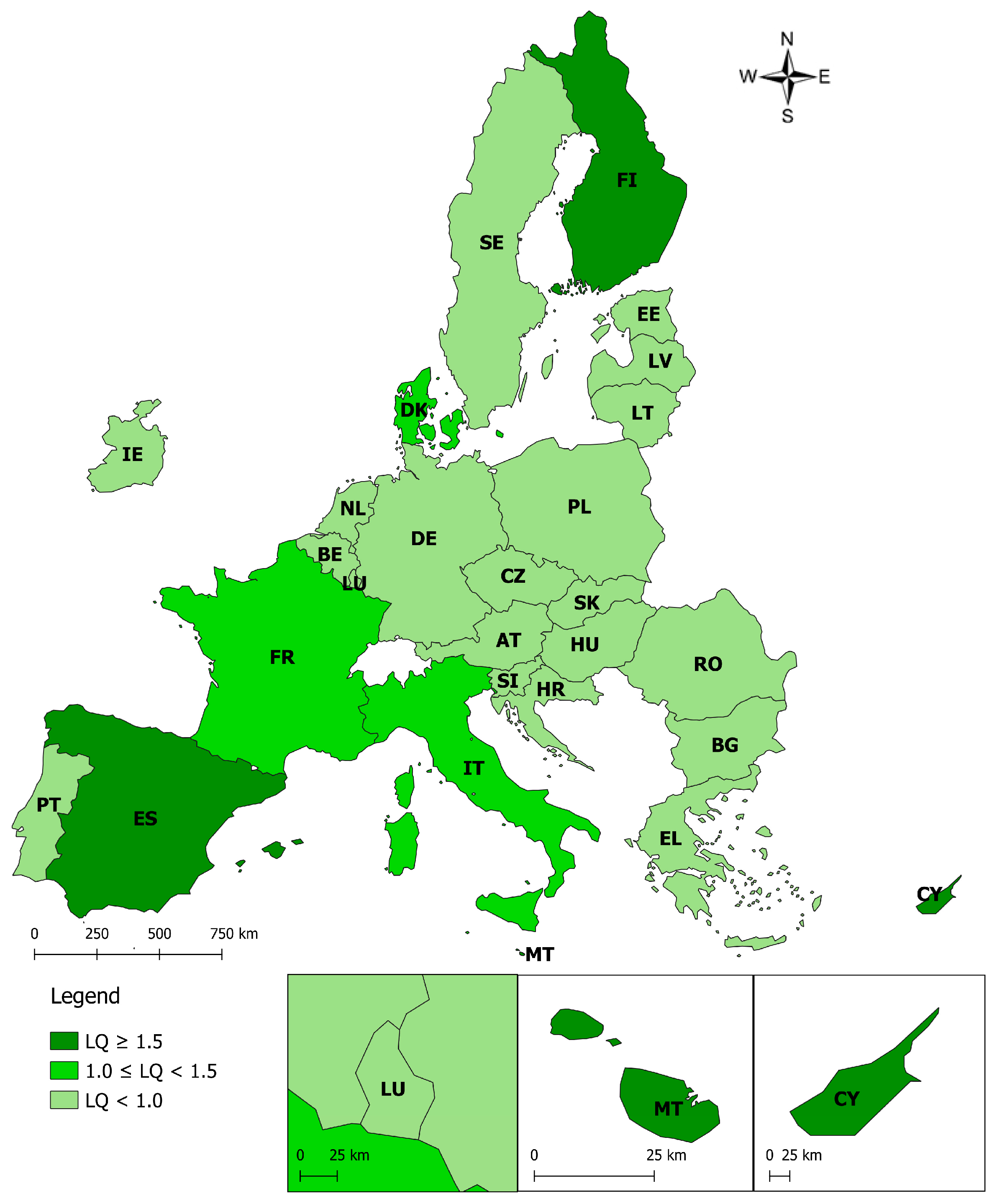

3.1. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Utilized Agricultural Area Excluding Kitchen Gardens (X2)

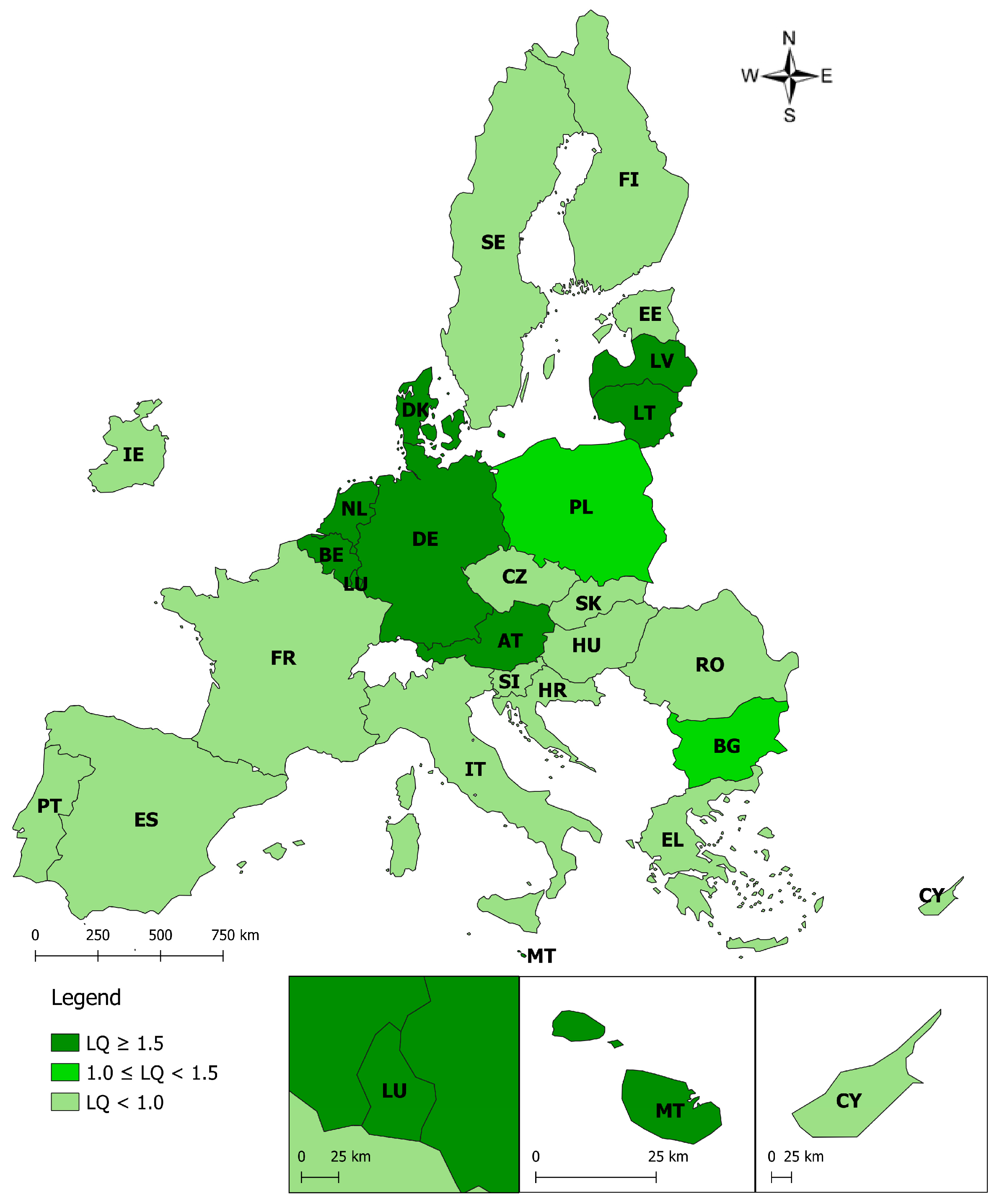

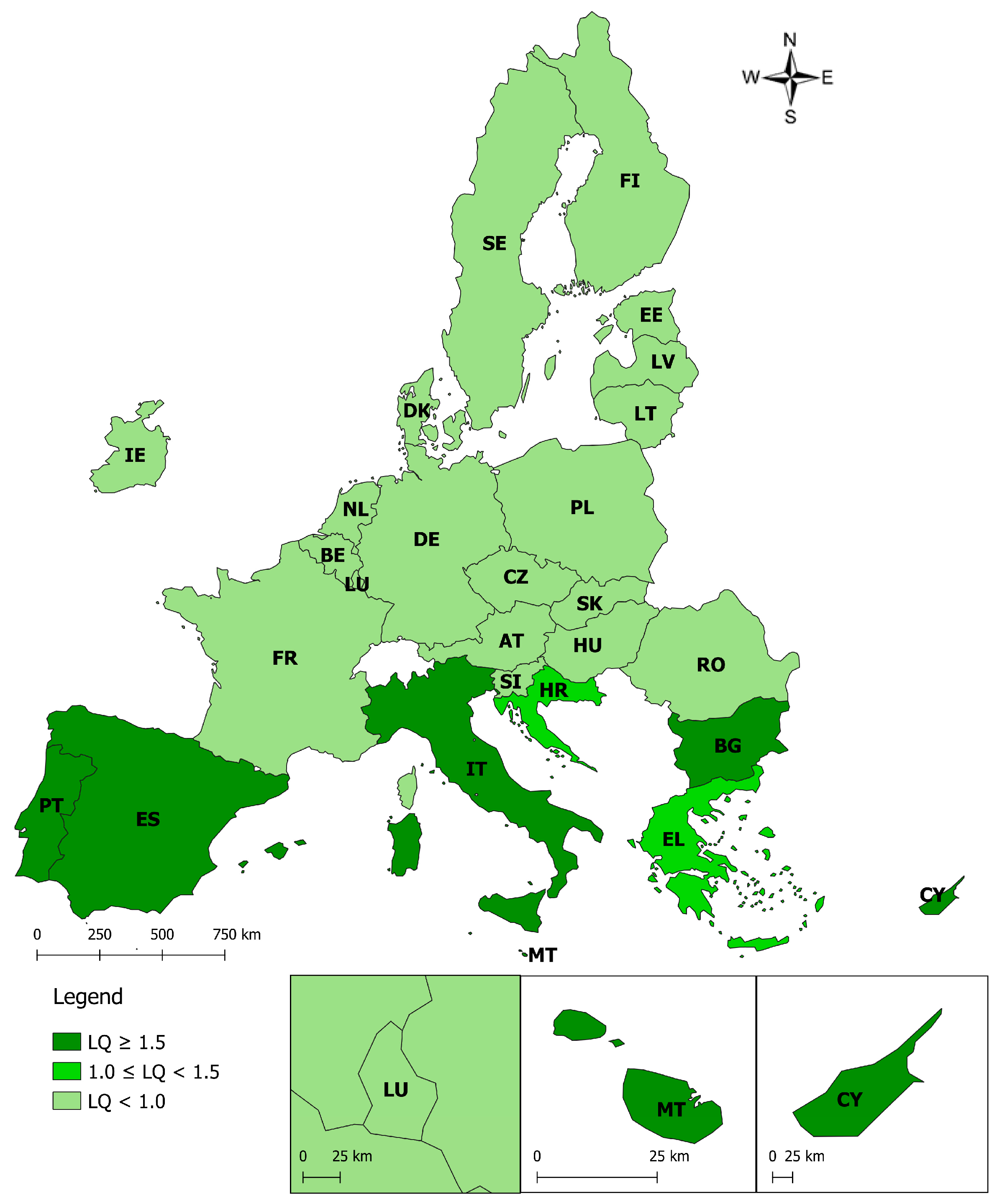

3.2. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Arable Land (X3)

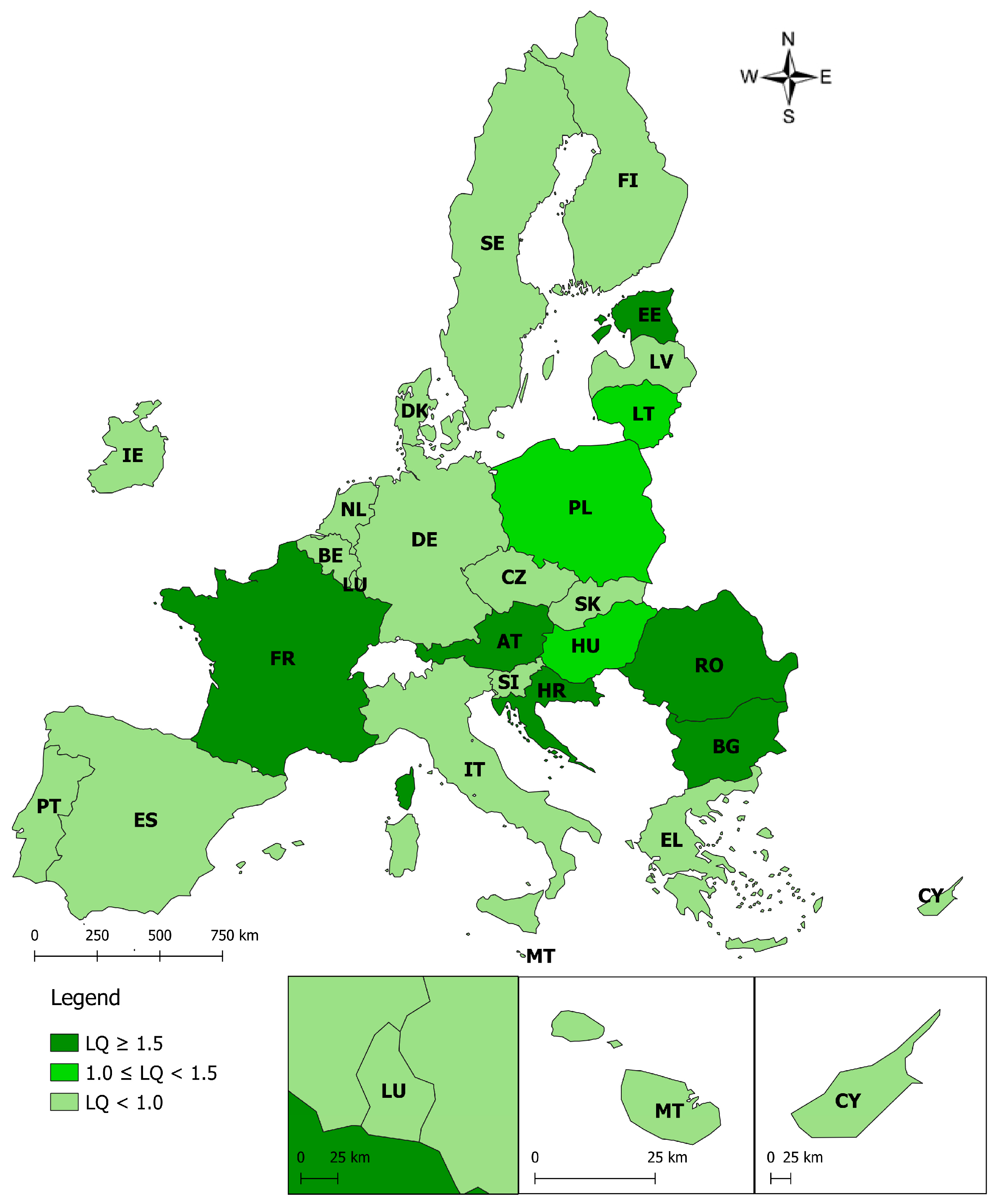

3.3. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Cereals Cultivated for Grain Production (Including Seed) (X4)

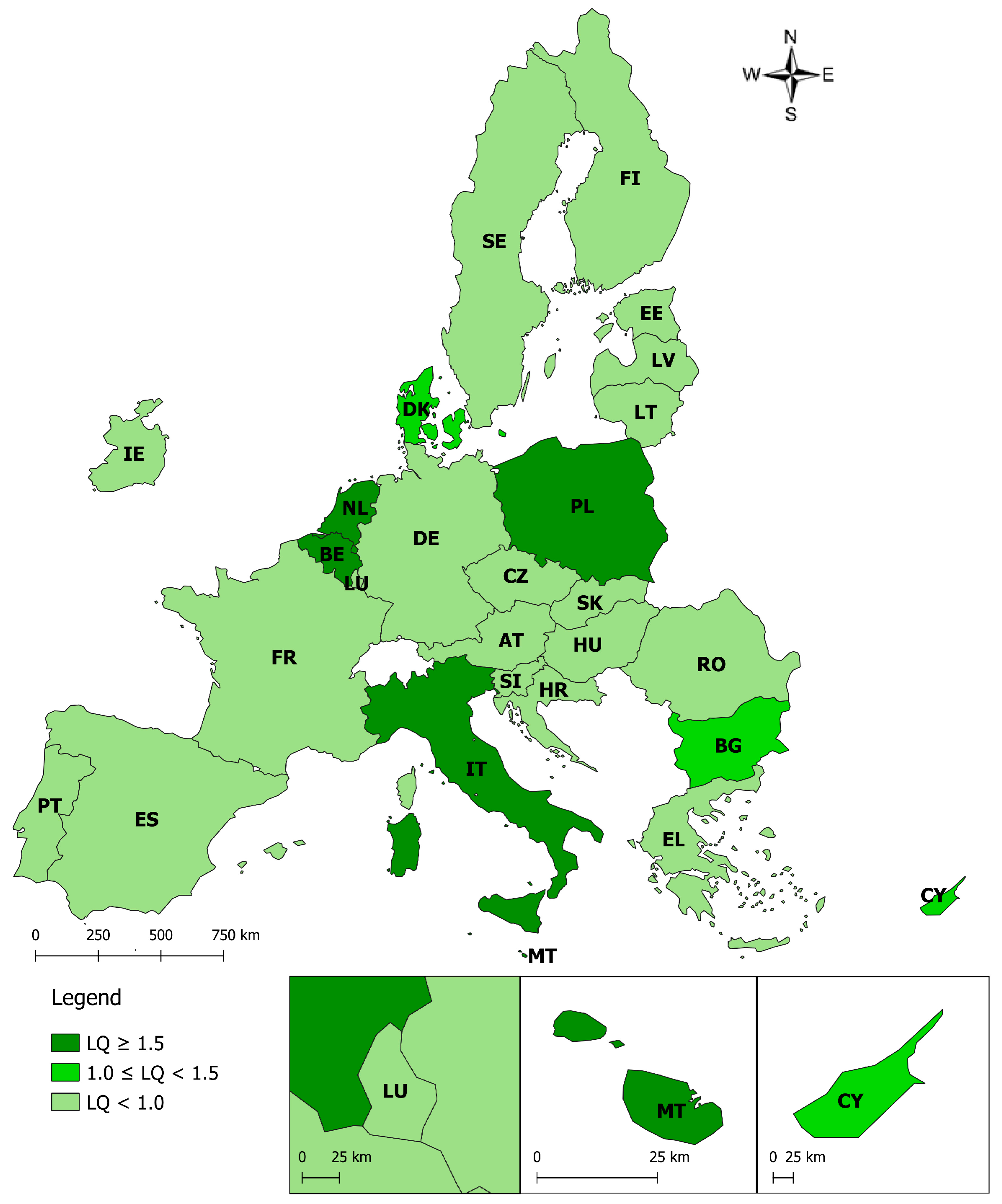

3.4. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Dry Pulses and Protein Crops for the Production of Grain (Including Seed and Mixtures of Cereals and Pulses) (X5)

3.5. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Root Crops (X6)

3.6. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Industrial Crops (X7)

3.7. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Green Plants Harvested from Arable Land (X8)

3.8. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Fresh Vegetables (Including Melons) and Strawberries (X9)

3.9. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Fallow Land (X10)

- X18—strong positive association (t = 4.055; p < 0.001),

- X19—positive association (t = 2.553; p = 0.019),

- X20—positive association (t = 2.633; p = 0.016),

- X22—negative association (t = −3.809; p = 0.001),

- X23—negative association (t = −4.007; p < 0.001).

3.10. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Permanent Grassland (X11)

- X18—negative predictor (t = −2.076; p = 0.050),

- X19—negative predictor (t = −3.499; p = 0.002),

- X22—positive predictor (t = 2.648; p = 0.015),

- X23—positive predictor (t = 2.962; p = 0.007).

3.11. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Permanent Crops (X12)

- X18—positive predictor (t = 3.619; p = 0.002),

- X19—positive predictor (t = 2.157; p = 0.043),

- X21—positive predictor (t = 3.270; p = 0.004),

- X22—negative predictor (t = −4.274; p < 0.001),

- X23—negative predictor, borderline significant (t = −2.048; p = 0.053).

3.12. Location Quotient (LQ) for Organic Permanent Crops for Human Consumption (X13)

- X18—positive predictor (t = 3.609; p = 0.002),

- X19—positive predictor (t = 2.128; p = 0.045),

- X21—positive predictor (t = 3.278; p = 0.004),

- X22—negative predictor (t = −4.260; p < 0.001),

- X23—negative predictor, borderline significant (t = −2.002; p = 0.058).

4. Discussion

- the dominant types of crops,

- the degree of production intensity,

- the relationship between domestic markets and export orientation,

- and the extent to which organic farming is embedded in local food systems.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable Code | Variable Name | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | LQ for Total fully converted and under conversion to organic farming | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X2 | LQ for Utilised agricultural area excluding kitchen gardens | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X3 | LQ for Arable land | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X4 | LQ for Cereals for the production of grain (including seed) | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X5 | LQ for Dry pulses and protein crops for the production of grain (including seed and mixtures of cereals and pulses) | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X6 | LQ for Root crops | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X7 | LQ for Industrial crops | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X8 | LG for Plants harvested green from arable land | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X9 | LQ for Fresh vegetables (including melons) and strawberries | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X10 | LQ for Fallow land | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X11 | LQ for Permanent grassland | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X12 | LQ for Permanent crops | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X13 | LQ for Permanent crops for human consumption | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops [online data code: org_cropar]; FAO: Agriculture area under organic agric., Cropland area certified organic |

| X14 | Organic retail sales share [%] | 2020 | FiBL survey based on national data sources, data from certifiers, Eurostat |

| X15 | Organic per capita consumption [€/person] | 2020 | FiBL survey based on national data sources, data from certifiers, Eurostat |

| X16 | Organic retail sales [Million €] | 2020 | FiBL survey based on national data sources, data from certifiers, Eurostat |

| X17 | Purchasing Power Standard (PPS) per adult equivalent | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Mean consumption expenditure per household and per adult equivalent [online data code: hbs_exp_t111] |

| X18 | Real expenditure per capita—Gross domestic product (in PPS_EU27_2020) | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices, and real expenditures for ESA 2010 aggregates [online data code: prc_ppp_ind] |

| X19 | Real expenditure per capita—Actual individual consumption (in PPS_EU27_2020) | 2020 | EUROSTAT: Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices, and real expenditures for ESA 2010 aggregates [online data code: prc_ppp_ind] |

| X20 | Human Development Index (value) | 2020 | UNDP All Composite Indices and Components Time Series (1990–2023) 2025. |

| X21 | Life Expectancy at Birth (years) | 2020 | UNDP All Composite Indices and Components Time Series (1990–2023) 2025. |

| X22 | Gross National Income Per Capita (2021 PPP$) | 2020 | UNDP All Composite Indices and Components Time Series (1990–2023) 2025. |

| X23 | Carbon dioxide emissions per capita (production) (tonnes) | 2020 | UNDP All Composite Indices and Components Time Series (1990–2023) 2025. |

| X24 | Population, total (millions) | 2020 | UNDP All Composite Indices and Components Time Series (1990–2023) 2025. |

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | X11 | X12 | X13 | X14 | X15 | X16 | X17 | X18 | X19 | X20 | X21 | X22 | X23 | X24 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | a | -- | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| b | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| X2 | a | 0.555 ** | -- | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| X3 | a | 0.062 | 0.031 | -- | |||||||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.760 | 0.880 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| X4 | a | 0.289 | 0.280 | 0.769 *** | -- | ||||||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.143 | 0.157 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| X5 | a | 0.492 ** | 0.303 | 0.548 ** | 0.714 *** | -- | |||||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.009 | 0.124 | 0.003 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| X6 | a | −0.214 | −0.127 | 0.422 * | 0.311 | 0.241 | -- | ||||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.283 | 0.528 | 0.028 | 0.114 | 0.225 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| X7 | a | 0.336 | 0.192 | 0.355 | 0.526 ** | 0.501 ** | −0.226 | -- | |||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.086 | 0.338 | 0.069 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.257 | |||||||||||||||||||

| X8 | a | 0.111 | 0.325 | 0.556 ** | 0.443 * | 0.243 | 0.100 | 0.051 | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| b | 0.583 | 0.098 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.223 | 0.621 | 0.799 | ||||||||||||||||||

| X9 | a | −0.137 | −0.426 * | 0.086 | −0.182 | −0.061 | 0.386 * | −0.289 | 0.101 | -- | |||||||||||||||

| b | 0.496 | 0.027 | 0.669 | 0.364 | 0.762 | 0.047 | 0.143 | 0.615 | |||||||||||||||||

| X10 | a | 0.179 | 0.014 | 0.469 * | 0.132 | 0.187 | 0.063 | 0.058 | 0.206 | 0.345 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| b | 0.370 | 0.945 | 0.014 | 0.512 | 0.350 | 0.753 | 0.774 | 0.303 | 0.078 | ||||||||||||||||

| X11 | a | −0.020 | 0.089 | −0.888 *** | −0.550 ** | −0.386 * | −0.269 | −0.260 | −0.460 * | −0.260 | −0.668 *** | -- | |||||||||||||

| b | 0.923 | 0.658 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.047 | 0.175 | 0.190 | 0.016 | 0.190 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||||

| X12 | a | −0.027 | −0.401 * | −0.056 | −0.261 | −0.165 | −0.200 | 0.098 | −0.220 | 0.504 ** | 0.426 * | −0.304 | -- | ||||||||||||

| b | 0.892 | 0.038 | 0.781 | 0.188 | 0.412 | 0.317 | 0.626 | 0.271 | 0.007 | 0.027 | 0.123 | ||||||||||||||

| X13 | a | −0.003 | −0.357 | −0.088 | −0.272 | −0.168 | −0.252 | 0.132 | −0.235 | 0.435 * | 0.393 * | −0.273 | 0.990 *** | -- | |||||||||||

| b | 0.988 | 0.068 | 0.663 | 0.170 | 0.402 | 0.206 | 0.512 | 0.238 | 0.023 | 0.043 | 0.168 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||

| X14 | a | 0.236 | 0.500 ** | 0.097 | 0.320 | 0.266 | 0.386 * | −0.025 | 0.369 | −0.002 | −0.152 | 0.076 | −0.472 * | −0.495 ** | -- | ||||||||||

| b | 0.237 | 0.008 | 0.630 | 0.104 | 0.180 | 0.047 | 0.901 | 0.058 | 0.990 | 0.448 | 0.705 | 0.013 | 0.009 | ||||||||||||

| X15 | a | 0.194 | 0.368 | 0.156 | 0.274 | 0.161 | 0.507 ** | −0.241 | 0.397 * | 0.158 | −0.037 | −0.037 | −0.308 | −0.353 | 0.900 *** | -- | |||||||||

| b | 0.333 | 0.059 | 0.438 | 0.167 | 0.424 | 0.007 | 0.227 | 0.040 | 0.433 | 0.854 | 0.856 | 0.118 | 0.071 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| X16 | a | 0.628 *** | 0.424 * | 0.053 | 0.249 | 0.310 | 0.298 | −0.100 | 0.309 | 0.168 | 0.003 | 0.032 | −0.214 | −0.242 | 0.761 *** | 0.810 *** | -- | ||||||||

| b | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.792 | 0.210 | 0.115 | 0.131 | 0.619 | 0.117 | 0.403 | 0.988 | 0.873 | 0.283 | 0.223 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| X17 | a | 0.023 | 0.165 | 0.046 | 0.037 | −0.120 | 0.449 * | −0.465 * | 0.347 | 0.341 | 0.150 | −0.038 | −0.190 | −0.242 | 0.660 *** | 0.827 *** | 0.584 ** | -- | |||||||

| b | 0.909 | 0.411 | 0.821 | 0.856 | 0.550 | 0.019 | 0.014 | 0.076 | 0.082 | 0.455 | 0.849 | 0.343 | 0.224 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| X18 | a | −0.089 | 0.066 | 0.068 | 0.074 | −0.107 | 0.595 ** | −0.560 ** | 0.213 | 0.275 | −0.081 | 0.031 | −0.400 * | −0.451 * | 0.670 *** | 0.802 *** | 0.542 ** | 0.850 *** | -- | ||||||

| b | 0.658 | 0.744 | 0.735 | 0.714 | 0.594 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.286 | 0.165 | 0.687 | 0.877 | 0.039 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| X19 | a | 0.122 | 0.145 | 0.203 | 0.285 | 0.085 | 0.583 ** | −0.413 * | 0.336 | 0.345 | 0.043 | −0.105 | −0.255 | −0.317 | 0.658 *** | 0.826 *** | 0.671 *** | 0.843 *** | 0.892 *** | -- | |||||

| b | 0.544 | 0.470 | 0.310 | 0.150 | 0.673 | 0.001 | 0.032 | 0.087 | 0.078 | 0.831 | 0.601 | 0.199 | 0.107 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| X20 | a | −0.012 | 0.221 | 0.080 | 0.083 | −0.030 | 0.555 ** | −0.521 ** | 0.320 | 0.214 | 0.005 | −0.014 | −0.408 * | −0.453 * | 0.688 *** | 0.812 *** | 0.595 ** | 0.868 *** | 0.890 *** | 0.808 *** | -- | ||||

| b | 0.953 | 0.268 | 0.692 | 0.680 | 0.882 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.104 | 0.284 | 0.982 | 0.943 | 0.035 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| X21 | a | 0.187 | 0.183 | −0.029 | −0.258 | −0.151 | 0.145 | −0.518 ** | 0.244 | 0.270 | 0.313 | −0.107 | −0.027 | −0.056 | 0.452 * | 0.582 ** | 0.519 ** | 0.716 *** | 0.626 *** | 0.516 ** | 0.688 *** | -- | |||

| b | 0.351 | 0.361 | 0.887 | 0.193 | 0.454 | 0.471 | 0.006 | 0.221 | 0.173 | 0.112 | 0.596 | 0.892 | 0.783 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | |||||

| X22 | a | 0.001 | 0.132 | 0.068 | 0.146 | −0.021 | 0.560 ** | −0.505 ** | 0.205 | 0.212 | −0.076 | 0.059 | −0.430 * | −0.482 * | 0.721 *** | 0.839 *** | 0.606 *** | 0.856 *** | 0.980 *** | 0.906 *** | 0.883 *** | 0.605 *** | -- | ||

| b | 0.995 | 0.510 | 0.735 | 0.468 | 0.917 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.305 | 0.289 | 0.707 | 0.772 | 0.025 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||||

| X23 | a | −0.158 | −0.001 | −0.314 | 0.013 | 0.034 | 0.214 | −0.272 | −0.027 | 0.119 | −0.630 *** | 0.405 * | −0.316 | −0.314 | 0.354 | 0.319 | 0.250 | 0.234 | 0.436 * | 0.436 * | 0.353 | −0.054 | 0.407 * | -- | |

| b | 0.433 | 0.998 | 0.110 | 0.949 | 0.866 | 0.283 | 0.170 | 0.892 | 0.554 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.108 | 0.111 | 0.070 | 0.105 | 0.209 | 0.240 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.071 | 0.790 | 0.035 | |||

| X24 | a | −0.405 * | 0.057 | 0.194 | 0.233 | −0.110 | 0.557 ** | −0.408 * | 0.343 | 0.010 | −0.162 | 0.017 | −0.601 *** | −0.626 *** | 0.507 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.178 | 0.648 *** | 0.780 *** | 0.634 *** | 0.724 *** | 0.278 | 0.748 *** | 0.424 * | -- |

| b | 0.036 | 0.778 | 0.333 | 0.242 | 0.584 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.080 | 0.961 | 0.418 | 0.933 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.374 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.161 | 0.000 | 0.028 | ||

References

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; World Commission on Environment and Development: Geneva, Switzerland; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zgurovsky, M. Impact of Information Society on Sustainable Development: Global and Regional Aspects. Data Sci. J. 2007, 6, S137–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dernbach, J.C.; Cheever, F. Sustainable Development and Its Discontents. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2015, 4, 247–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, I.; Pawlewicz, K.; Pawlewicz, A. Sustainable Development in Polish Regions: A Shift-Share Analysis. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 28, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatucci, C.; Mollo, G. Sustainable Growth and the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Improving the Circular Economy. In Digital Technologies and Distributed Registries for Sustainable Development; Sannikova, L.V., Ed.; Law, Governance and Technology Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 64, pp. 25–42. ISBN 978-3-031-51066-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lábaj, M.; Luptáčik, M.; Nežinský, E. Data Envelopment Analysis for Measuring Economic Growth in Terms of Welfare beyond GDP. Empirica 2014, 41, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.D.S.; Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. The Traditional Energy-Growth Nexus: A Comparison between Sustainable Development and Economic Growth Approaches. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 75, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimeris, P.; Bithas, K.; Richardson, C.; Nijkamp, P. Hidden Linkages between Resources and Economy: A “Beyond-GDP” Approach Using Alternative Welfare Indicators. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, Y. A Better Strategy: Using Green GDP to Measure Economic Health. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1459764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Esposito, M.; Kapoor, A. Circular Economy Business Models in Developing Economies: Lessons from India on Reduce, Recycle, and Reuse Paradigms. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 60, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. An Integrated Circular Economy Model for Transformation towards Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, D.; Kirmani, S.B.R.; Masoodi, F.A. Circular Economy in the Food Systems: A Review. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2025, 34, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of the Regions the European Green Deal (COM/2019/640 Final) 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52019DC0640 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- EC Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of the Regions, a Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System (COM/2020/381 Final) 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/farm-to-fork-strategy-for-a-fair-healthy-and-environmentally-friendly-food-system.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Grzybowska-Brzezińska, M.; Lizińska, W.; Grzywińska-Rąpca, M.; Kuberska, D.; Marks-Bielska, R. Perspektywa Funkcjonowania i Rozwoju Gospodarstw Rolnych w Warunkach Realizacji Założeń Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu: Na przykładzie woj. Warmińsko-Mazurskiego; Instytut Badań Gospodarczych: Olsztyn, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-65605-71-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros-Casanova, I.; Cristiano, A.; Biancolini, D.; Cimatti, M.; Sessa, A.A.; Mendez Angarita, V.Y.; Dragonetti, C.; Pacifici, M.; Rondinini, C.; Di Marco, M. Opportunities and Challenges for Common Agricultural Policy Reform to Support the European Green Deal. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigoreanu, I.; Ungureanu, B.A.; Ungureanu, G.; Ignat, G. Analysis of Sustainable Energy and Environmental Policies in Agriculture in the EU Regarding the European Green Deal. Energies 2024, 17, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faichuk, O.; Pashchenko, O.; Zharikova, O.; Sotnyk, V.; Faichuk, O. Economic and Environmental Aspects of Agri-Food System in the EU Member States and Ukraine in Context of the European Green Deal Objectives. Environ. Technol. Resour. 2025, 1, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.; Slaveva, K.; Pavlov, P. Organic Agriculture in the Republic of Bulgaria: A Model for Sustainable Development and Diversification of Agricultural Business. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeremešić, S.; Dolijanović, Ž.; Simin, M.T.; Vojnov, B.; Trbić, D.G. The Future We Want: Sustainable Development Goals Accomplishment with Organic Agriculture. Probl. Ekorozw. 2021, 16, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrik, U.A. Securing Planetary Health and Sustainable Food Systems with Global Organic Agriculture: Best Practice from Austria: Attaining 40% by 2030 and 100% by 2040: In Combination with Other Measures. In Case Studies on Sustainability in the Food Industry; Idowu, S.O., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Management for Professionals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–48. ISBN 978-3-031-07741-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Gamage, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Kodikara, N.; Suraweera, P.; Merah, O. Role of Organic Farming for Achieving Sustainability in Agriculture. Farm. Syst. 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pânzaru, R.L.; Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Ciobanu, A.; Medelete, D.M.; Pîrvu, R. Organic Agriculture in the Context of 2030 Agenda Implementation in European Union Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska, B.; Borawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A. The Development of Organic Agriculture in Poland in the Context of the European Union: Perspectives under the European Green Deal. In Problemy Rozwoju Agrobiznesu, Obszarów Wiejskich i Bezpieczeństwa Żywnościowego w Polsce na Tle Unii Europejskiej; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A., Żuchowski, I., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Ostrołęckiego Towarzystwa Naukowego im. Adama Chętnika: Ostrołęka, Poland, 2024; pp. 15–42. ISBN 978-83-62775-81-1. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, M.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Naidu, R.; Bari, A.S.M.F.; Singh, A.B.; Thakur, J.K.; Ghosh, A.; Patra, A.K.; Chaudhari, S.K.; Subbarao, A. Organic Farming: A Prospect for Food, Environment and Livelihood Security in Indian Agriculture. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 170, pp. 101–153. ISBN 978-0-12-824591-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, D.; Dubey, P.K.; Chaurasiya, R.; Sankar, A.; Shikha, M.; Chatterjee, N.; Ganguly, S.; Meena, V.S.; Meena, S.K.; Parewa, H.P.; et al. Organic Interventions Conferring Stress Tolerance and Crop Quality in Agroecosystems during the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4797–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Louws, F.J.; Creamer, N.G.; Paul Mueller, J.; Brownie, C.; Fager, K.; Bell, M.; Hu, S. Responses of Soil Microbial Biomass and N Availability to Transition Strategies from Conventional to Organic Farming Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 113, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, P.; Panwar, N.; Singh, A.B.; Ramana, S.; Yadav, S.K.; Shrivastava, R.; Rao, A.S. Status of Organic Farming in India. Curr. Sci. 2010, 98, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Environmental Impact of Different Agricultural Management Practices: Conventional vs. Organic Agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, A.; Gotkiewicz, W.; Brodzińska, K.; Pawlewicz, K.; Mickiewicz, B.; Kluczek, P. Organic Farming as an Alternative Maintenance Strategy in the Opinion of Farmers from Natura 2000 Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombi, G.; Martani, E.; Fornara, D. Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Soil Ecosystem Service Delivery: A Literature Review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2025, 73, 101721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Food Quality Assessment in Organic vs. Conventional Agricultural Produce: Findings and Issues. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Organic Agriculture: Impact on the Environment and Food Quality. In Environmental Impact of Agro-Food Industry and Food Consumption; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 31–58. ISBN 978-0-12-821363-6. [Google Scholar]

- Giampieri, F.; Mazzoni, L.; Cianciosi, D.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Regolo, L.; Sánchez-González, C.; Capocasa, F.; Xiao, J.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. Organic vs Conventional Plant-Based Foods: A Review. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källström, H.N.; Ljung, M. Social Sustainability and Collaborative Learning. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2005, 34, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.L. Social Learning among Organic Farmers and the Application of the Communities of Practice Framework. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2011, 17, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M.; Getz, C.; Kraus, S.; Montenegro, M.; Holland, K. The Social Dimensions of Sustainability and Change in Diversified Farming Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, art41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, L.; Lamine, C.; Navarrete, M. Short Food Supply Chains, Long Working Days: Active Work and the Construction of Professional Satisfaction in French Diversified Organic Market Gardening. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanz, L.; Oehen, B.; Benoit, M.; Bernes, G.; Magne, M.-A.; Martin, G.; Winckler, C. High Work Satisfaction despite High Workload among European Organic Mixed Livestock Farmers: A Mixed-Method Approach. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Hendriks, K.; Stortelder, A. Phenology of the Landscape: The Role of Organic Agriculture. Landsc. Res. 2004, 29, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I. Organic Farming and Rural Development: Some Evidence from Austria. Sociol. Rural. 2005, 45, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, C. Organic Agriculture Enhances Agrobiodiversity. Biodiversity 2008, 9, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobley, M.; Butler, A.; Reed, M. The Contribution of Organic Farming to Rural Development: An Exploration of the Socio-Economic Linkages of Organic and Non-Organic Farms in England. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reganold, J.P.; Wachter, J.M. Organic Agriculture in the Twenty-First Century. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondhi, N.; Vani, V. An Empirical Analysis of the Organic Retail Market in the NCR. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2007, 8, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.R.-D.; Lim, W.-M. Why Do Consumers Buy Organic Food? Results from an S–O–R Model. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghikhah, F.; Voinov, A.; Shukla, N.; Filatova, T. Exploring Consumer Behavior and Policy Options in Organic Food Adoption: Insights from the Australian Wine Sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Ali, S.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Fogarassy, C.; Lakner, Z. Why Organic Food? Factors Influence the Organic Food Purchase Intension in an Emerging Country (Study from Northern Part of Bangladesh). Resources 2023, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R.; Obidzińska, J.; Szumigaj, B.; Dobrowolski, H.; Rembiałkowska, E. Sustainable Foods: Consumer Opinions and Behaviour towards Organic Fruits in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, C.G.; Madsen, N.A.; Jacobsen, B.H. Organic Farming Scenarios: Operational Analysis and Costs of Implementing Innovative Technologies. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 91, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, A. Change of Price Premiums Trend for Organic Food Products: The Example of the Polish Egg Market. Agriculture 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Parsons, R.; Wang, Q.; Conner, D. What Makes an Organic Dairy Farm Profitable in the United States? Evidence from 10 Years of Farm Level Data in Vermont. Agriculture 2020, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujianto, S.; Ariningsih, E.; Ashari, A.; Wulandari, S.; Wahyudi, A.; Gunawan, E. Investigating the Financial Challenges and Opportunities of Organic Rice Farming: An Empirical Long-Term Analysis of Smallholder Farmers. Org. Agric. 2024, 14, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, C.; Wossink, A.; Giesen, G.; Huirne, R. Ecological-Economic Modelling to Support Multi-Objective Policy Making: A Farming Systems Approach Implemented for Tuscany. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 102, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M.; Morin, L.; Hahn, T.; Sandahl, J. Institutional Barriers to Organic Farming in Central and Eastern European Countries of the Baltic Sea Region. Agric. Econ. 2013, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczka, W. Institutional Conditions for Strengthening the Position of Organic Farming as a Component of Sustainable Development. Probl. Ekorozw. 2021, 16, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Nieberg, H.; Offermann, F. Financial Relevance of Organic Farming Payments for Western and Eastern European Organic Farms. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2008, 23, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleemann, L.; Abdulai, A. Organic Certification, Agro-Ecological Practices and Return on Investment: Evidence from Pineapple Producers in Ghana. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grovermann, C.; Quiédeville, S.; Muller, A.; Leiber, F.; Stolze, M.; Moakes, S. Does Organic Certification Make Economic Sense for Dairy Farmers in Europe?–A Latent Class Counterfactual Analysis. Agric. Econ. 2021, 52, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczka, W.; Kalinowski, S.; Shmygol, N. Organic Farming Support Policy in a Sustainable Development Context: A Polish Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Kopiński, J. Productive, Environmental and Economic Effects of Organic and Conventional Farms—Case Study from Poland. Agronomy 2024, 14, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, J. A Europeanization Deficit? The Impact of EU Organic Agriculture Regulations on New Member States. J. Eur. Public Policy 2008, 15, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennig, P.; Sauer, J. Promoting Organic Food Production through Flagship Regions. Q Open 2022, 2, qoac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.; Grovermann, C.; Finger, R. National Organic Action Plans and Organic Farmland Area Growth in Europe. Food Policy 2023, 121, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Canio, F.; Martinelli, E. EU Quality Label vs Organic Food Products: A Multigroup Structural Equation Modeling to Assess Consumers’ Intention to Buy in Light of Sustainable Motives. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelaers, K.; Verbeke, W.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Importance of Health and Environment as Quality Traits in the Buying Decision of Organic Products. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1120–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rana, J. Consumer Behavior and Purchase Intention for Organic Food. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukasovič, T. Consumers’ Perceptions and Behaviors Regarding Organic Fruits and Vegetables: Marketing Trends for Organic Food in the Twenty-First Century. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2016, 28, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer Behavior and Purchase Intention for Organic Food: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, I.; Griffith, D.M.; Aguirre, I. Understanding the Factors Limiting Organic Consumption: The Effect of Marketing Channel on Produce Price, Availability, and Price Fairness. Org. Agric. 2021, 11, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saysel, A.K.; Barlas, Y.; Yenigün, O. Environmental Sustainability in an Agricultural Development Project: A System Dynamics Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2002, 64, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenes-Muñoz, T.; Lakner, S.; Brümmer, B. What Influences the Growth of Organic Farms? Evidence from a Panel of Organic Farms in Germany. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 65, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshchalykina, A.; Kyryliuk, Y.; Kyryliuk, I. Prerequisites for the Development and Prospects of Organic Agricultural Products Market. J. Entrepren. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithner, M.; Fikar, C. A Simulation Model to Investigate Impacts of Facilitating Quality Data within Organic Fresh Food Supply Chains. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 314, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzoughi, N. Farmers Adoption of Integrated Crop Protection and Organic Farming: Do Moral and Social Concerns Matter? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läpple, D.; Kelley, H. Understanding the Uptake of Organic Farming: Accounting for Heterogeneities among Irish Farmers. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipidis, P.; Karypidou, S. Factors That Impact Farmers’ Organic Conversion Decisions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapbamrer, R.; Thammachai, A. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Farmers’ Adoption of Organic Farming. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; Schneeberger, W.; Freyer, B. Converting or Not Converting to Organic Farming in Austria:Farmer Types and Their Rationale. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, A.; Kaczmarczyk, T.; Oczyńska, S. Opportunities and Barriers to the Functioning of Organic Farming in the Opinion of Organic Farm Owners. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywn. 2010, 85, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remeikiene, R.; Gaspareniene, L. Green Farming Development Opportunities: The Case of Lithuania. Oecon. Copernic. 2017, 8, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczka, W.; Kalinowski, S. Barriers to the Development of Organic Farming: A Polish Case Study. Agriculture 2020, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczka, W. Procesy Rozwojowe Rolnictwa Ekologicznego i Ich Ekonomiczno-Społeczne Uwarunkowania; Wydanie Pierwsze; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-66849-02-0. [Google Scholar]

- Markuszewska, I.; Kubacka, M. Does Organic Farming (OF) Work in Favour of Protecting the Natural Environment? A Case Study from Poland. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, H.S.; Kakar, R.; Kumar, N. Seema Impact of Organic and Conventional Farming Practices on Soil Quality: A Global Review. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, C.S.; Sharma, S.; Thakur, M.; Kaur, P. A Review of the Influences of Organic Farming on Soil Quality, Crop Productivity and Produce Quality. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 1884–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S. Conversion to Organic Farming: A Typical Example of the Diffusion of an Innovation? Sociol. Rural. 2001, 41, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C.; Bellon, S. Conversion to Organic Farming: A Multidimensional Research Object at the Crossroads of Agricultural and Social Sciences. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śpiewak, R.; Jasiński, J. Organic Farming as a Rural Development Factor in Poland—The Role of Good Governance and Local Policies. Int. J. Food Syst. Dynam. 2020, 11, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Nam, Q.; Tiet, T. The Role of Peer Influence and Norms in Organic Farming Adoption: Accounting for Farmers’ Heterogeneity. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Vecchio, R. Key Factors Influencing Farmers’ Adoption of Sustainable Innovations: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Org. Agric. 2024, 14, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granatstein, D.; Kirby, E.; Willer, H. Current World Status of Organic Temperate Fruits. Acta Hortic. 2010, 873, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bórawski, P.; Bórawski, M.B.; Parzonko, A.; Wicki, L.; Rokicki, T.; Perkowska, A.; Dunn, J.W. Development of Organic Milk Production in Poland on the Background of the EU. Agriculture 2021, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobocińska, K.; Łukiewska, K. Development of Organic Agriculture in Selected Countries of the European Union. Econ. Environ. 2024, 89, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiewski, J. Changes in the Import of Organic Products to the European Union between 2018 and 2023. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2024, XXVI, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, S.; Žukovskis, J.; Gozdowski, D.; Cieśliński, M.; Wójcik-Gront, E. Evaluating the Path to the European Commission’s Organic Agriculture Goal: A Multivariate Analysis of Changes in EU Countries (2004–2021) and Socio-Economic Relationships. Agriculture 2024, 14, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiewska, B.; Pajewski, T. Changes in the Development Trends of Organic Farming in the World. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2025, XXVII, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muska, A.; Pilvere, I.; Viira, A.-H.; Muska, K.; Nipers, A. European Green Deal Objective: Potential Expansion of Organic Farming Areas. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, E.; Boere, E.; Krisztin, T.; Verburg, P.H. Enabling and Constraining Factors for Organic Agriculture in Europe: A Spatial Analysis. Environ. Res. Food Syst. 2025, 2, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, P.; Langer, V. Localisation and Concentration of Organic Farming in the 1990s—The Danish Case. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2004, 95, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, J.; Moineddin, R. Methods for Confidence Interval Estimation of a Ratio Parameter with Application to Location Quotients. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djira, G.D.; Schaarschmidt, F.; Fayissa, B. Inferences for Selected Location Quotients with Applications to Health Outcomes. Geogr. Anal. 2010, 42, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humaidi, E.; Kertayoga, I.P.A.W.; Analianasari. Preparation of a Map of Leading Food Commodities in the Lampung Province Using the Location Quotient (LQ) Method. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1012, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuberska, D.; Juchniewicz, M. Spatial Evolution of Organic Farmland in Poland. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2024, XXVI, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, Z.; Ağızan, K.; Ağızan, S. Determination of Location Quotient of Organic Agriculture in Türkiye. Tekirdağ Ziraat Fak. Derg. 2025, 22, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çukur, F.; Işin, F.; Çukur, T. Determination of the Relationship between Organic Farming Area and Agricultural Added Value in Some European Union Countries with Panel ARDL Analysis. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2021, 19, 5007–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Kobiałka, A. The Significance of Organic Farming in the European Union from the Perspective of Sustainable Development. Ekon. Sr. 2024, 88, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociszewski, K.; Krupowicz, J.; Graczyk, A.; Sobocińska, M.; Mazurek-Łopacińska, K. The Supply-Side of the Organic Food Market in the Light of Relations between Farmers and Distributors. Ekon. Sr. 2024, 88, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhring, N.; Muller, A.; Schaub, S. Farmers’ Adoption of Organic Agriculture—A Systematic Global Literature Review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2024, 51, 1012–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komor, A.; Pawlak, J.; Wróblewska, W.; Białoskurski, S.; Czernyszewicz, E. Spatial Differentiation of the Competitiveness of Organic Farming in EU Countries in 2014–2023: An Input–Output Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozumowska, W.; Soliwoda, M.; Kulawik, J.; Galnaitytė, A.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Organic Farming in Lithuania and Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Foster, C. Exploring the Gap between Attitudes and Behaviour: Understanding Why Consumers Buy or Do Not Buy Organic Food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic Food Consumption in Poland: Motives and Barriers. Appetite 2016, 105, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulescu, V.; Cetina, I.; Cruceru, A.F.; Goldbach, D. Consumers’ Attitude and Intention towards Organic Fruits and Vegetables: Empirical Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, A.; Zemaitiene, R.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Bielski, S. Assessment of the Environmental Public Goods of the Organic Farming System: A Lithuanian Case Study. Agriculture 2024, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Aslan, I.; Jarosz-Angowska, A. Drivers of Organic Product Consumption in the EU: A Sustainable Development Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 7245–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociszewski, K. Perspectives of Polish Organic Farming Development in the Aspect of the European Green Deal. Ekon. Sr. 2022, 81, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solfanelli, F.; Ozturk, E.; Dudinskaya, E.C.; Mandolesi, S.; Orsini, S.; Messmer, M.; Naspetti, S.; Schaefer, F.; Winter, E.; Zanoli, R. Estimating Supply and Demand of Organic Seeds in Europe Using Survey Data and MI Techniques. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubska, N. Organic Animal Products in the EU to Support Sustainable Consumption. Comparat. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2025, 28, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, F.A.; Rennie, D. Consumer Perceptions Towards Organic Food. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.S.; Agarwal, S.; Dev, V.; Gupta, A.; Chauhan, S. Optimizing Organic Food Sustainability Through Digital Platforms for Enhanced SEO. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICTACS), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 1 November 2023; IEEE: Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2023; pp. 608–613. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Yilmaz, B. Organic Food Production: Innovation and Sustainable Practice, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-003-37147-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tzouramani, I.; Liontakis, A.; Sintori, A.; Alexopoulos, G. Exploring Organic Cherry Investment Opportunities for Greek Farmers. Outlook Agric. 2013, 42, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnhagen, K.P.; Clemens, S.; Eriksson, D.; Fresco, L.O.; Tosun, J.; Qaim, M.; Visser, R.G.F.; Weber, A.P.M.; Wesseler, J.H.H.; Zilberman, D. Europe’s Farm to Fork Strategy and Its Commitment to Biotechnology and Organic Farming: Conflicting or Complementary Goals? Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 1st ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-471-18386-0. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Methodology in the Social Sciences; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-60623-639-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2021; ISBN 978-0-9875071-3-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, C. The Analysis of Time Series, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-203-49168-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.L. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data; Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, 1st ed.; CRC Press reprint; Chapman & Hall; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-412-04061-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys, 1st ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-471-08705-2. [Google Scholar]

- Isserman, A.M. The Location Quotient Approach to Estimating Regional Economic Impacts. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1977, 43, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, G.; Glaeser, E.L. Geographic Concentration in U.S. Manufacturing Industries: A Dartboard Approach. J. Political Econ. 1997, 105, 889–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The Analysis of Spatial Association by Use of Distance Statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S. Location Quotient and Trade. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2009, 43, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Gottlieb, P.D.; Goetz, S.J. Measuring Industry Co-Location across County Borders. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2020, 15, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.N. Measuring Size Distortions of Location Quotients. Int. Econ. 2021, 167, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pominova, M.; Gabe, T.; Crawley, A. The Stability of Location Quotients. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2022, 52, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimowicz, A.; Rzeczkowski, D. New Measure of Economic Development Based on the Four-Colour Theorem. Entropy 2020, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) 2025. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Advanced Issues and Deeper Insights. In Model Selection and Multimodel Inference; Burnham, K.P., Anderson, D.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 267–351. ISBN 978-0-387-95364-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. Linear Methods for Regression. In The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 43–99. ISBN 978-0-387-84857-0. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Linear Model Selection and Regularization. In An Introduction to Statistical Learning; Springer Texts in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 225–288. ISBN 978-1-0716-1417-4. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar, D.E.; Glauber, R.R. Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis: The Problem Revisited. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1967, 49, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-262-23258-6. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed.; Global Edition; Pearson: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-292-23113-6. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-19424-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G. To Explain or to Predict? Statist. Sci. 2010, 25, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual Quant 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. Basis Expansions and Regularization. In The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 139–189. ISBN 978-0-387-84857-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge Regression: Biased Estimation for Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N. Many Shades of Gray—The Context-Dependent Performance of Organic Agriculture. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ušča, M.; Ieviņa, L.; Lakovskis, P. Spatial Disparity and Environmental Issues of Organic Agriculture. Agron. Res. 2023, 21, 1374–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, C.; Bravo, C.; De León, D.G.; Magaña, M.; Alonso, J.C. Effects of Organic Farming on Plant and Arthropod Communities: A Case Study in Mediterranean Dryland Cereal. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 141, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudisca, S.; di Trapani, A.M.; Sgroi, F.; Testa, R. Organic Farming and Economic Sustainability: The Case of Sicilian Durum Wheat. Qual. Access Success 2014, 15, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jelínková, Z.; Moudrý, J.; Bernas, J.; Kopecký, M.; Moudrý, J.; Konvalina, P. Environmental and Economic Aspects of Triticum Aestivum L. and Avena Sativa Growing. Open Life Sci. 2016, 11, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moudry, J.; Bernas, J.; Kopecky, M.; Konvalina, P.; Bucur, D.; Moudry, J.; Kolar, L.; Sterba, Z.; Jelinkova, Z. Influence of Farming System on Greenhouse Gas Emissions within Cereal Cultivation. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varia, F.; Macaluso, D.; Vaccaro, A.; Caruso, P.; Guccione, G.D. The Adoption of Landraces of Durum Wheat in Sicilian Organic Cereal Farming Analysed Using a System Dynamics Approach. Agronomy 2021, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földi, M.; Bencze, S.; Hertelendy, P.; Veszter, S.; Kovács, T.; Drexler, D. Farmer Involvement in Agro-Ecological Research: Organic on-Farm Wheat Variety Trials in Hungary and the Slovakian Upland. Org. Agric. 2022, 12, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, A. Beef Cattle Farms’ Conversion to the Organic System. Recommendations for Success in the Face of Future Changes in a Global Context. Sustainability 2016, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Morales, M.D.; Marmolejo-Martín, J.A. The Waring Distribution as a Low-Frequency Prediction Model: A Study of Organic Livestock Farms in Andalusia. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-i-Gelats, F.; Filella, J.B. Examining the Role of Organic Production Schemes in Mediterranean Pastoralism. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 5771–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Miranda, M.; Fouz, R.; Orjales, I.; Diéguez, F.J.; Minervino, A.H.H.; López-Alonso, M. Breed Performance in Organic Dairy Farming in Northern Spain. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2020, 55, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faux, A.-M.; Decruyenaere, V.; Guillaume, M.; Stilmant, D. Feed Autonomy in Organic Cattle Farming Systems: A Necessary but Not Sufficient Lever to Be Activated for Economic Efficiency. Org. Agric. 2022, 12, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, C.R.; Friedrich, H.; McAfee, J. Organic Fruit Production: Challenges and Opportunities for Research and Outreach. Acta Hortic. 2007, 737, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granatstein, D.; Kirby, E.; Willer, H. Global Area and Trends of Organic Fruit Production. Acta Hortic. 2013, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gorriz, B.; Gallego-Elvira, B.; Martínez-Alvarez, V.; Maestre-Valero, J.F. Life Cycle Assessment of Fruit and Vegetable Production in the Region of Murcia (South-East Spain) and Evaluation of Impact Mitigation Practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, D.; Carver, S.J.; Durham, H.; Kunin, W.E.; Palmer, R.C.; Sait, S.M.; Stagl, S.; Benton, T.G. The Spatial Aggregation of Organic Farming in England and Its Underlying Environmental Correlates. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P.; Stagl, S.; Franks, D.W. Simulating the Diffusion of Organic Farming Practices in Two New EU Member States. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2580–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschitz, H.; Stolze, M. Organic Farming Policy Networks in Europe: Context, Actors and Variation. Food Policy 2009, 34, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.O.; Denver, S.; Zanoli, R. Actual and Potential Development of Consumer Demand on the Organic Food Market in Europe. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 58, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milestad, R.; Hadatsch, S. Growing out of the Niche—Can Organic Agriculture Keep Its Promises? A Study of Two Austrian Cases. Am. J. Alt. Agric. 2003, 18, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Parras-Rosa, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J. Influence of the Commercial Distribution Model on the Surcharge for Organic Foods in Spain. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Loeillet, D.; Dawson, C.; Lescot, T. A Paradox: Mercantile Organic against Sustainability in Europe? Acta Hortic. 2023, 284, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, A.; Brodzinska, K.; Zvirbule, A.; Popluga, D. Trends in the Development of Organic Farming in Poland and Latvia Compared to the EU. Rural Sustain. Res. 2020, 43, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, D.W.; Reganold, J.P. Financial Competitiveness of Organic Agriculture on a Global Scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7611–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, A. Regional Diversity of Organic Food Sales in the European Union. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference “Economic Science for Rural Development”, Jelgava, Lettonia, 9–10 May 2019; pp. 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- Batáry, P.; Dicks, L.V.; Kleijn, D.; Sutherland, W.J. The Role of Agri-environment Schemes in Conservation and Environmental Management. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, C. Assessing the Socio-Economic Dimensions of the Rise of Organic Farming in the European Union. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2016, 74, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, C. Capitalism in Green Disguise: The Political Economy of Organic Farming in the European Union. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2018, 50, 830–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.; Murtagh, A.; Weir, L.; Conway, S.F.; McDonagh, J.; Mahon, M. Irish Organics, Innovation and Farm Collaboration: A Pathway to Farm Viability and Generational Renewal. Sustainability 2021, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, B.; Poczta-Wajda, A.; Matuszczak, A.; Smędzik-Ambroży, K.; Guth, M. Exploring Intentions to Convert into Organic Farming in Small-Scale Agriculture: Social Embeddedness in Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour Framework. Agric. Syst. 2025, 225, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.; Murdoch, J. Organic vs. Conventional Agriculture: Knowledge, Power and Innovation in the Food Chain. Geoforum 2000, 31, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Zasada, I.; Bruszewska, K.; Skoczowski, B.; Piorr, A. Potentials and Limitations of Regional Organic Food Supply: A Qualitative Analysis of Two Food Chain Types in the Berlin Metropolitan Region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drejerska, N.; Sobczak-Malitka, W. Nurturing Sustainability and Health: Exploring the Role of Short Supply Chains in the Evolution of Food Systems—The Case of Poland. Foods 2023, 12, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region Type | Characteristics of the Organic Production Model | Dominant LQ Categories | Example Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nordic–Baltic Model (Cereal–Forage Based) | Organic farming based on extensive arable land, dominance of cereals, protein crops, and green fodder; strong livestock sector. | X3 (arable land), X4 (cereals), X5 (protein crops), X8 (green fodder) | Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland |

| 2. Alpine–Central European Model (Grassland Based) | Extensive production systems relying on permanent grasslands; strong cattle-rearing traditions; high overall share of organic farming. | X11 (permanent grassland), X8 (green fodder), X2 (overall organic share) | Austria, Germany, Slovakia, Slovenia, partly Czechia |

| 3. Mediterranean Model (High-Value Permanent Crops) | Organic farming concentrated in orchards, vineyards, olive groves, and other perennial crops; high added value and export orientation. | X12 (permanent crops), X13 (permanent crops for consumption), X9 (vegetables) | Spain, Italy, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus |

| 4. Central–Eastern European Model (Raw-Material Oriented) | Organic production focused on cereals, industrial crops, and protein crops; large farms and export-oriented raw-material production. | X4 (cereals), X5 (protein crops), X7 (industrial crops) | Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Hungary |

| 5. Western European Intensive Model (Horticultural) | Intensive organic horticulture, including vegetables and root crops; high specialization and strong local markets. | X9 (vegetables), X6 (root crops), X10 (fallow land—specific cases) | Netherlands, Belgium, Malta |

| 6. Island and Micro-State Model (Niche Specializations) | Spatially constrained organic farming with extreme LQ values in selected categories; niche-oriented production. | X9 (vegetables), X10 (fallow land), X12–X13 (permanent crops) | Malta, Cyprus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pawlewicz, A.; Pawlewicz, K. Spatial and Economic Differentiation of Land Use for Organic Farming in the European Union. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031454

Pawlewicz A, Pawlewicz K. Spatial and Economic Differentiation of Land Use for Organic Farming in the European Union. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031454

Chicago/Turabian StylePawlewicz, Adam, and Katarzyna Pawlewicz. 2026. "Spatial and Economic Differentiation of Land Use for Organic Farming in the European Union" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031454

APA StylePawlewicz, A., & Pawlewicz, K. (2026). Spatial and Economic Differentiation of Land Use for Organic Farming in the European Union. Sustainability, 18(3), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031454