Soil Microbial Responses to Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid) Copolymers Addition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Soil Sampling and Preparation

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Synthesis of Cross-Linked Acrylic Polyelectrolytes (PAA)

2.5. Modification of Starch Phosphates (SP)

2.6. Method for Preparation of Starch Phosphate Graft (Acrylic Acid) Copolymers

2.6.1. Starch Phosphate-g-Poly(acrylic acid) Copolymer (SP1-g-PAA)

2.6.2. Starch Phosphate-g-Poly(acrylic acid) Copolymer (SP2-g-PAA)

2.7. Measurement of the Water Absorption Capacity of the SAP Polymer

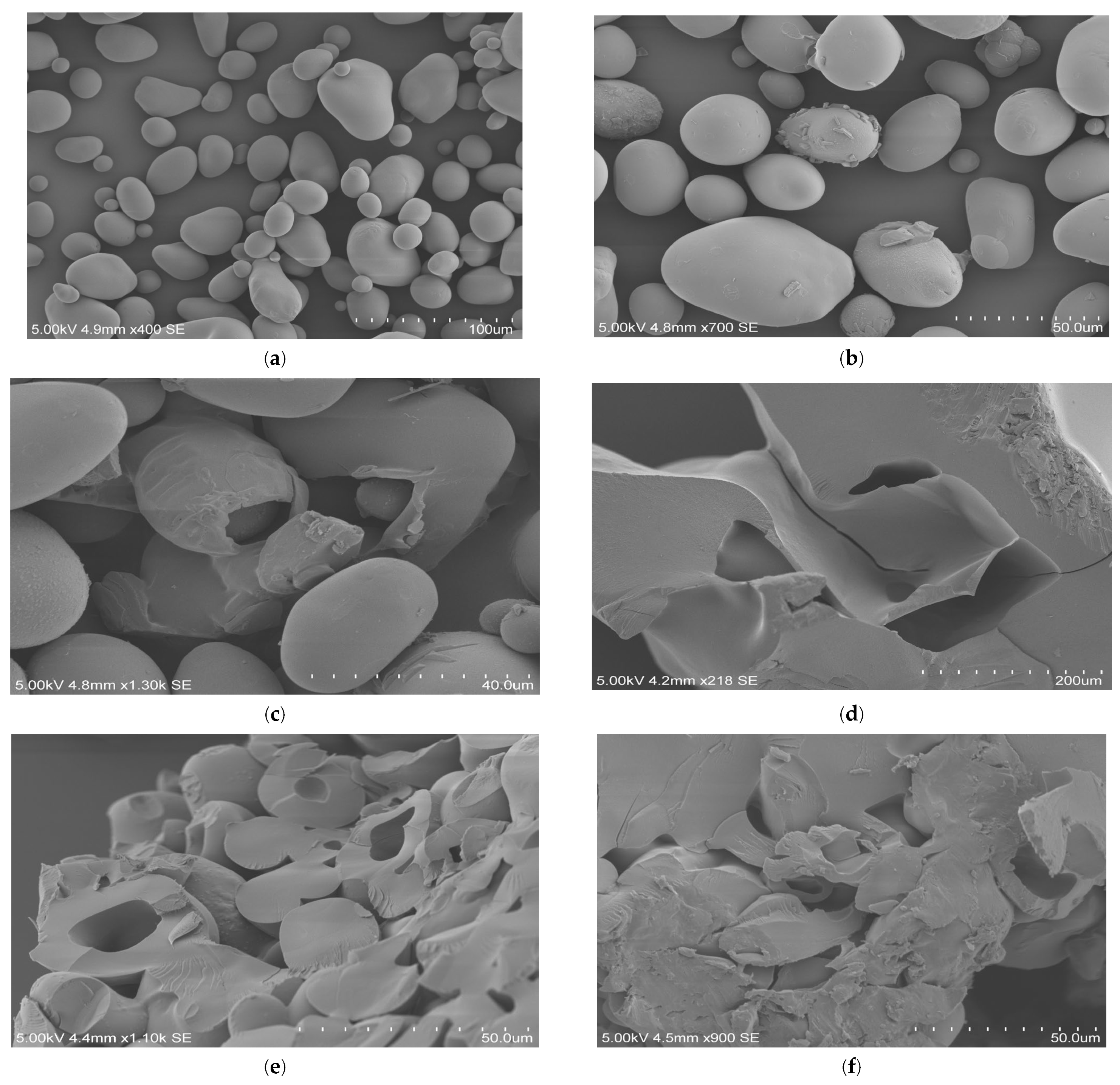

2.8. Surface Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.9. Microbial and Biochemical Analyses

2.10. Measurement of Chemical and Physical Properties

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

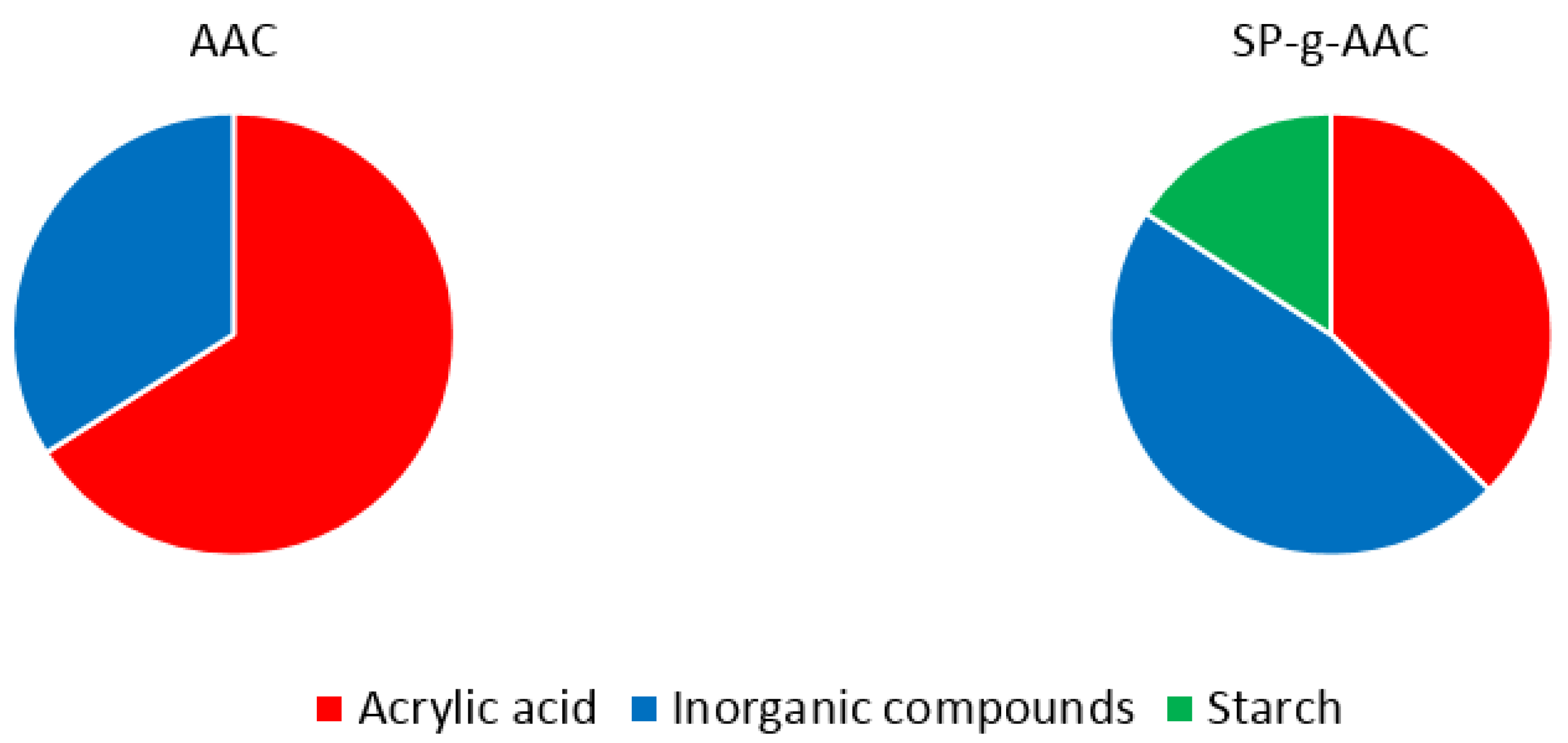

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of SP1-g-PAA and SP2-g-PAA Polymers

3.1.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

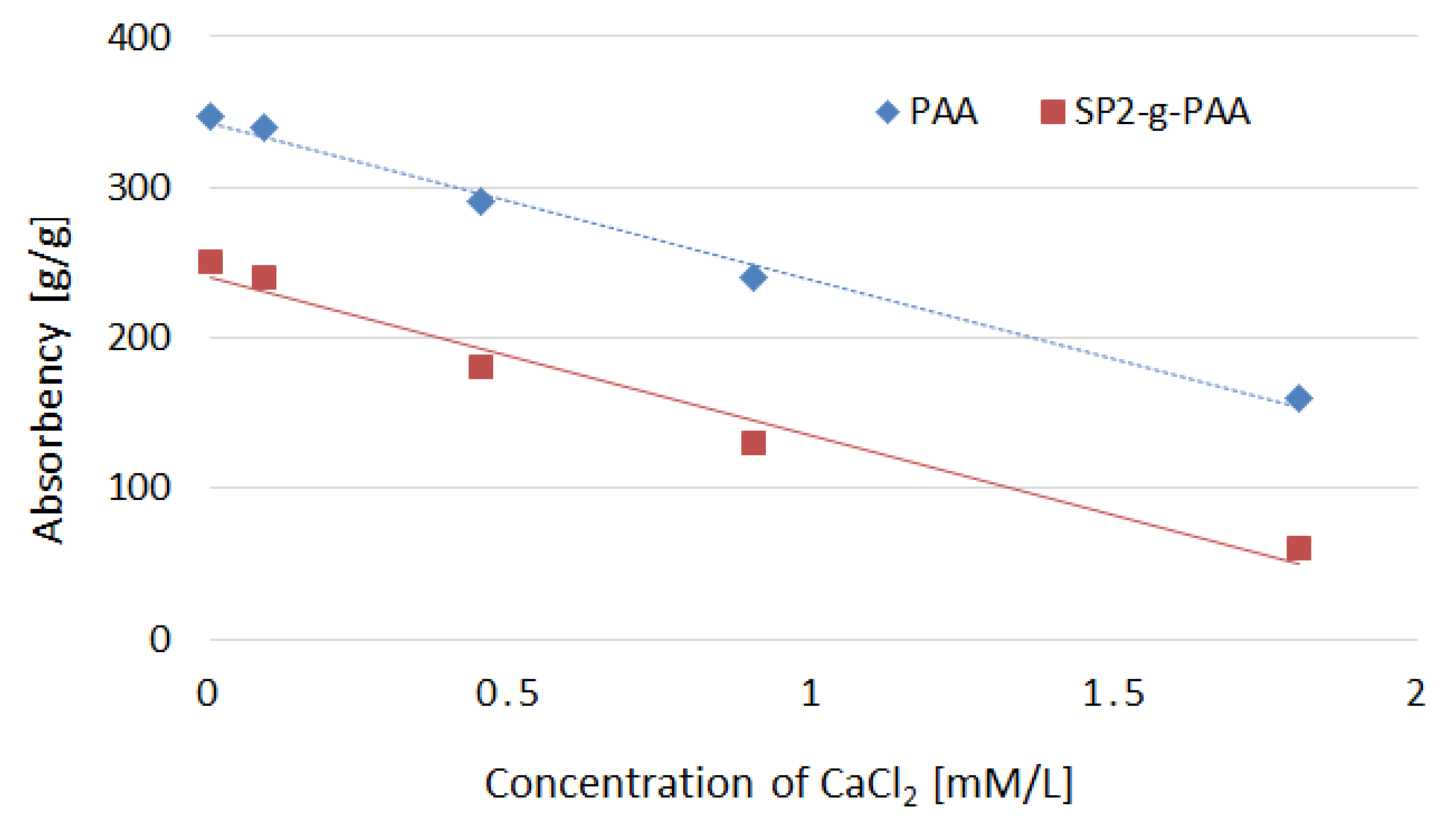

3.1.2. SAPs Absorption in Distilled Water and Solutions of CaCl2 and 0.9% NaCl

3.1.3. The Content of Various Phosphorus Fractions in the Obtained Polymers

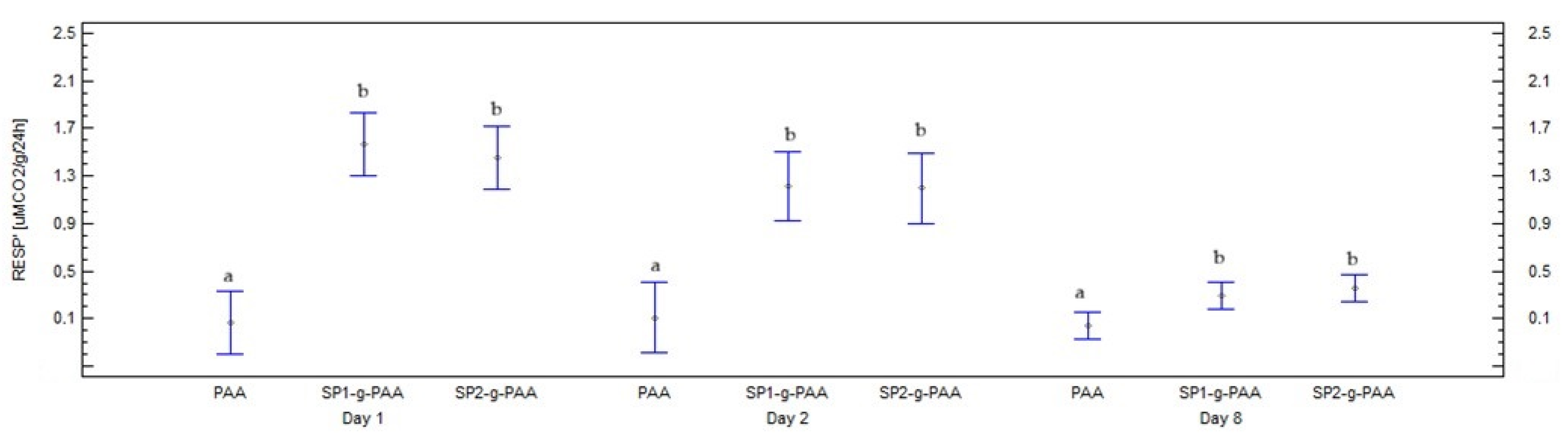

3.2. The Effect of PAA and SP-g-PAA Polymers on Microbial Activity and the Content of Various Phosphorus Fractions in Soil

3.2.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of Soils

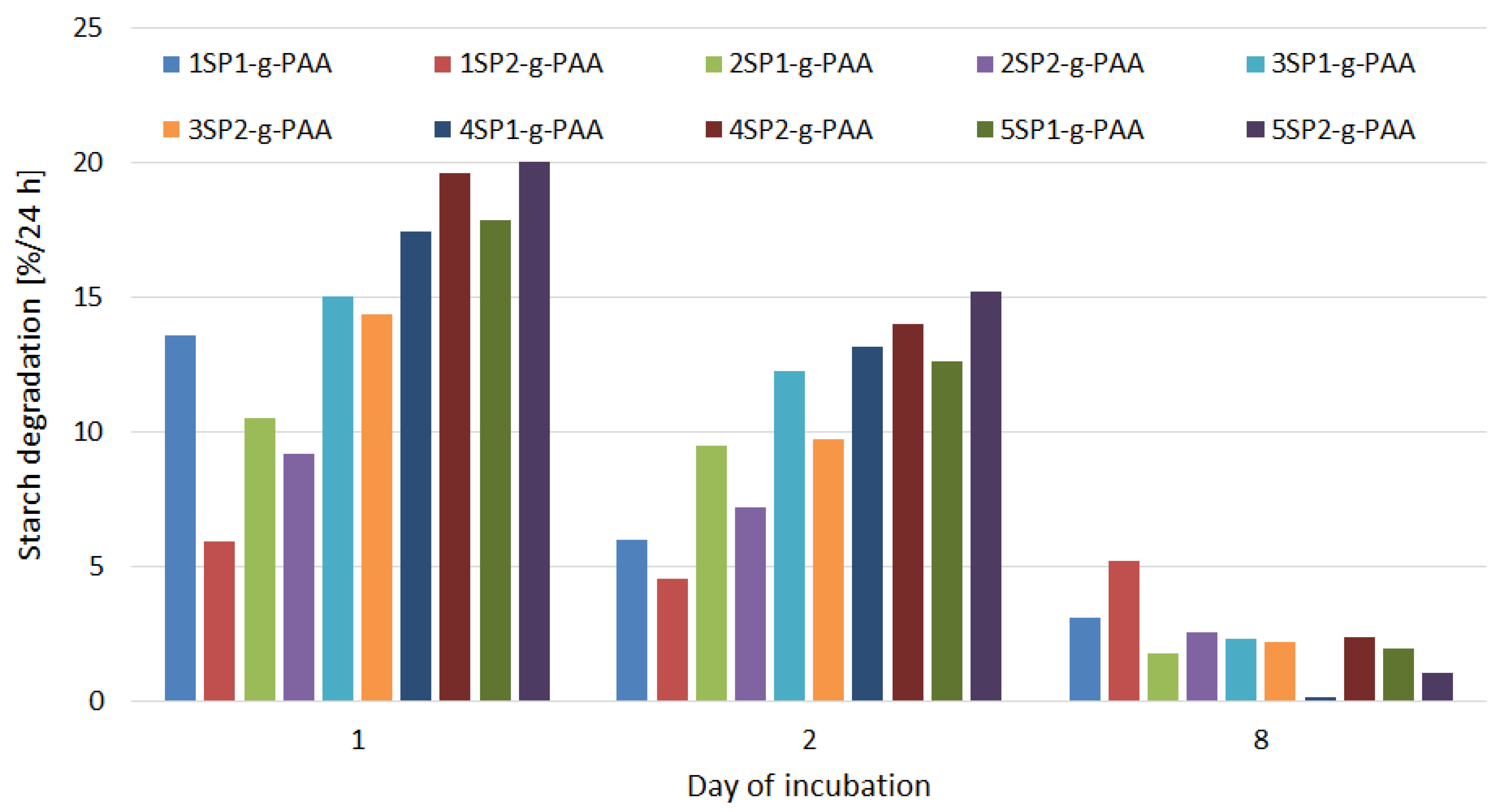

3.2.2. Soil Respiration with Polymer Additives

- PLS—Degradation of starch hydrogel [%/24 h]

- RESPSP-g-PAA—Soil respiration with SP-g-PAA added [μmol CO2/g/24 h]

- RESPPAA—Soil respiration with PAA added [μmol CO2/g/24 h]

- 162.14—Molar mass of glucopyranose unit (C6H10O5) [g/mol]

- 6—Stoichiometric coefficient

- 0.2—Percentage of SAP content in the soil [%]

- 16—Percentage of starch in SAP [%]

3.2.3. Phosphorus Fraction Content in Soil After the Incubation Period

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Corg | organic carbon content |

| Nt | total phosphorus content |

| PAA | poly(acrylic acid), lightly crosslinked |

| Pi | labile inorganic phosphorus content |

| Pmic | microbial phosphorus |

| Porg | labile organic phosphorus content |

| Pt | total phosphorus content |

| PT | labile total phosphorus content |

| RESP | soil respiration |

| SAP | superabsorbent polymer |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| SP-g-PAA | starch-phosphates-g-poly(acrylic acid), lightly crosslinked |

References

- Mahgoub, M.; ElBelasy, A.; Abdelmonem, Y.; Soussa, H.; Elalfy, E. Impact of Urbanization and Climate Change on Soil Erosion in Semi-Arid Basins. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W. Effects of Climate and Land Use/Cover Change on Soil Erosion in the Qinba Mountains. J. Geogr. Sci. 2025, 35, 1459–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, F.; Rahman, A. An Overview of Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture and Their Mitigation Strategies. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, I.; Epelde, L.; Garbisu, C. Environmental Parameters Altered by Climate Change Affect the Activity of Soil Microorganisms Involved in Bioremediation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, fnx200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poreda, A.; Tuszyński, T.; Zdaniewicz, M.; Sroka, P.; Jakubowski, M. Support Materials for Yeast Immobilization Affect the Concentration of Metal Ions in the Fermentation Medium. J. Inst. Brew. 2013, 119, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, P.; Satora, P.; Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A. The Influence of Yeast Immobilization on Selected Parameters of Young Meads. J. Inst. Brew. 2017, 123, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ahmed, S. Recent Advances in Edible Polymer Based Hydrogels as a Sustainable Alternative to Conventional Polymers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6940–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnopeeva, E.L.; Panova, G.G.; Yakimansky, A.V.; Krasnopeeva, E.L.; Panova, G.G.; Yakimansky, A.V. Agricultural Applications of Superabsorbent Polymer Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denagbe, W.; Mazet, E.; Desbrières, J.; Michaud, P. Superabsorbent Polymers: Eco-Friendliness and the Gap between Basic Research and Industrial Applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 214, 106278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyyssölä, A.; Ahlgren, J. Microbial Degradation of Polyacrylamide and the Deamination Product Polyacrylate. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 139, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksińska, M.P.; Magnucka, E.G.; Lejcuś, K.; Pietr, S.J. Biodegradation of the Cross-Linked Copolymer of Acrylamide and Potassium Acrylate by Soil Bacteria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 5969–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksińska, M.P.; Magnucka, E.G.; Lejcuś, K.; Jakubiak-Marcinkowska, A.; Ronka, S.; Trochimczuk, A.W.; Pietr, S.J. Colonization and Biodegradation of the Cross-Linked Potassium Polyacrylate Component of Water Absorbing Geocomposite by Soil Microorganisms. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 133, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytán, I.; Burelo, M.; Loza-Tavera, H. Current Status on the Biodegradability of Acrylic Polymers: Microorganisms, Enzymes and Metabolic Pathways Involved. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smagin, A.V.; Sadovnikova, N.B.; Belyaeva, E.A.; Korchagina, C.V. Biodegradability of Gel-Forming Superabsorbents for Soil Conditioning: Kinetic Assessment Based on CO2 Emissions. Polymers 2023, 15, 3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shi, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Han, F.; Xu, M. Study on Preparation and Properties of Super Absorbent Gels of Homogenous Cotton Straw-Acrylic Acid-Acrylamide by Graft Copolymerization. Gels 2025, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, R.; Yuan, Z.; Sosa, D.; Johnson, A.; Beims, R.F.; Li, H.; Wei, Q.; Xu, C.C. Performance of a Novel, Eco-Friendly, Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Polymer (Cellulo-SAP): Absorbency, Stability, Reusability, and Biodegradability. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 1762–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Qu, J.; Tan, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, T.; Yang, H.; Peng, J.; Zhai, M. Synthesis and Property of Superabsorbent Polymer Based on Cellulose Grafted 2-Acrylamido-2-Methyl-1-Propanesulfonic Acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodangeh, F.; Nabipour, H.; Rohani, S.; Xu, C. Applications, Challenges and Prospects of Superabsorbent Polymers Based on Cellulose Derived from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 408, 131204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, E.; Nowaczyk, J. Synthesis and Characterization Superabsorbent Polymers Made of Starch, Acrylic Acid, Acrylamide, Poly(Vinyl Alcohol), 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate, 2-Acrylamido-2-Methylpropane Sulfonic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, E.; Nowaczyk, J. Semi-Natural Superabsorbents Based on Starch-g-Poly(Acrylic Acid): Modification, Synthesis and Application. Polymers 2020, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Qi, W.; Yue, L.; Ye, Q. Synthesis and Characterisation of Starch Grafted Superabsorbent via 10 MeV Electron-Beam Irradiation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, A.; Puspasari, T.; Pratama, H. Utilization of Cassava Starch in Copolymerisation of Superabsorbent Polymer Composite (SAPC). J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2014, 46, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, M.; Schmidt, B.; Spychaj, T. Starch Graft Copolymers as Superabsorbents Obtained via Reactive Extrusion Processing. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2010, 12, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witono, J.R.; Noordergraaf, I.W.; Heeres, H.J.; Janssen, L.P.B.M. Water Absorption, Retention and the Swelling Characteristics of Cassava Starch Grafted with Polyacrylic Acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q. Salt-Tolerant Superabsorbent Polymer with High Capacity of Water-Nutrient Retention Derived from Sulfamic Acid-Modified Starch. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 5923–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta Chaudhuri, S.; Mandal, A.; Dey, A.; Chakrabarty, D. Tuning the Swelling and Rheological Attributes of Bentonite Clay Modified Starch Grafted Polyacrylic Acid Based Hydrogel. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 185, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.; Irani, M.; Ahmad, Z. Starch-Based Hydrogels: Present Status and Applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2013, 62, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Liu, X.; Yu, L.; Qiao, D.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, N. Synthesis and Characterization of Biodegradable Starch-Polyacrylamide Graft Copolymers Using Starches with Different Microstructures. J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanthong, P.; Nuisin, R.; Kiatkamjornwong, S. Graft Copolymerization, Characterization, and Degradation of Cassava Starch-g-Acrylamide/Itaconic Acid Superabsorbents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 66, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Roychowdhury, V.; Ghosh, S. Starch in Food Applications. In Biopolymers in Pharmaceutical and Food Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F. Starch Based Films and Coatings for Food Packaging: Interactions with Phenolic Compounds. Food Res. Int. 2025, 204, 115758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compart, J.; Singh, A.; Fettke, J.; Apriyanto, A. Customizing Starch Properties: A Review of Starch Modifications and Their Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzyk, S.; Fortuna, T. Oxidation-Induced Changes in the Surface Structure of Starch Granules. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2005, 55, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Otache, M.A.; Duru, R.U.; Achugasim, O.; Abayeh, O.J. Advances in the Modification of Starch via Esterification for Enhanced Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladinov, V.D.; Hanna, M.A. Starch Esterification by Reactive Extrusion. Ind. Crops Prod. 2000, 11, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, M.; Cao, T.; Xu, W. The Effect of Acetylation on the Physicochemical Properties of Chickpea Starch. Foods 2023, 12, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Namazi, H. Developments on Carboxymethyl Starch-Based Smart Systems as Promising Drug Carriers: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 258, 117654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia Bangar, S.; Sunooj, K.V.; Navaf, M.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Whiteside, W.S. Recent Advancements in Cross-Linked Starches for Food Applications—A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłek, J.; Lamkiewicz, J. The Starch Hydrolysis by α-Amylase Bacillus spp.: An Estimation of the Optimum Temperatures, the Activation and Deactivation Energies. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 14459–14466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczak, W.; Bidzińska, E.; Dyrek, K.; Fornal, J.; Michalec, M.; Wenda, E. Effect of Phosphorylation and Pretreatment with High Hydrostatic Pressure on Radical Processes in Maize Starches with Different Amylose Contents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passauer, L.; Bender, H.; Fischer, S. Synthesis and Characterisation of Starch Phosphates. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passauer, L.; Liebner, F.; Fischer, K. Starch Phosphate Hydrogels. Part I: Synthesis by Mono-Phosphorylation and Cross-Linking of Starch. Starch-Stärke 2009, 61, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passauer, L.; Liebner, F.; Fischer, K. Starch Phosphate Hydrogels. Part II: Rheological Characterization and Water Retention. Starch-Stärke 2009, 61, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagai, M.K.; Fletcher, B.; Witt, T.; Dhital, S.; Flanagan, B.M.; Gidley, M.J. Multiple Length Scale Structure-Property Relationships of Wheat Starch Oxidized by Sodium Hypochlorite or Hydrogen Peroxide. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangseethong, K.; Termvejsayanon, N.; Sriroth, K. Characterization of Physicochemical Properties of Hypochlorite- and Peroxide-Oxidized Cassava Starches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, K.; Sroka, P. Superabsorbent Hydrogels in the Agriculture and Reclamation of Degraded Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamruzzaman, M.; Ahmed, F.; Mondal, M.I.H. An Overview on Starch-Based Sustainable Hydrogels: Potential Applications and Aspects. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kovar, J.L. Fractionation of Soil Phosphorus. In Methods of Phosphorus Analysis for Soils, Sediments, Residuals, and Waters, 2nd ed.; Kovar, J.L., Pierzynski, G.M., Eds.; Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin No. 408; Virginia Tech University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2009; pp. 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, R.A.; Cole, C.V. Transformations of Organic Phosphorus Substrates in Soils as Evaluated by NaHCO3 Extraction. Soil Sci. 1978, 125, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, E.; Blume, H.P. Bodenkundliches Praktikum; Verlag Paul Parey: Hamburg, Germany, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Park, K. Synthesis and Characterization of Superporous Hydrogel Composites. J. Control. Release 2000, 65, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wack, H. Method and Model for the Analysis of Gel-Blocking Effects during the Swelling of Polymeric Hydrogels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 46, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, T.; Liu, M.; Hu, M.; Li, J. Synthesis, Characterization, and Swelling Behaviors of Salt-Sensitive Maize Bran–Poly(Acrylic Acid) Superabsorbent Hydrogel. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8867–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situ, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, C.; Liang, S.; Mao, X.; Chen, X. Effects of Several Superabsorbent Polymers on Soil Exchangeable Cations and Crop Growth. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Kosaka, I.; Ohta, S. Water Retention Characteristics of Superabsorbent Polymers (SAPs) Used as Soil Amendments. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, R.; Balogun, Y.; Oluyemi, G.; Njuguna, J. Swelling Performance of Sodium Polyacrylate and Poly(Acrylamide-Co-Acrylic Acid) Potassium Salt. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 2, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, K.; Sroka, P.; Santos, L.; Baptista, C. CO2 Emission from Soils Under the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Addition and Polymer Superabsorbent Application. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, E.; Tatari, A.; Firouzabadi, M.D. Preparation, Characteristics, and Soil-Biodegradable Analysis of Corn Starch/Nanofibrillated Cellulose (CS/NFC) and Corn Starch/Nanofibrillated Lignocellulose (CS/NFLC) Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 309, 120699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaj-Bokharaei, S.; Zadeh, B.; Etesami, H.; Motamedi, E. Effect of Hydrogel Composite Reinforced with Natural Char Nanoparticles on Improvement of Soil Biological Properties and the Growth of Water Deficit-Stressed Tomato Plant. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 223, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjuik, T.A.; Nokes, S.E.; Montross, M.D. Biodegradability of Bio-Based and Synthetic Hydrogels as Sustainable Soil Amendments: A Review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, C.; Neff, J.; Meyer, M.; Bundschuh, M.; Steinmetz, Z. Superabsorbent Polymers in Soil: The New Microplastics? Camb. Prism. Plast. 2024, 2, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Motesharezadeh, B. Starch-g-Poly(Acrylic Acid-Co-Acrylamide) Composites Reinforced with Natural Char Nanoparticles toward Environmentally Benign Slow-Release Urea Fertilizers. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanan, W.; Panichpakdee, J.; Suwanakood, P.; Saengsuwan, S. Biodegradable Hydrogels of Cassava Starch-g-Polyacrylic Acid/Natural Rubber/Polyvinyl Alcohol as Environmentally Friendly and Highly Efficient Coating Material for Slow-Release Urea Fertilizers. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 101, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacholczak, A.; Nowakowska, K.; Monder, M.J. Starch-Based Superabsorbent Enhances the Growth and Physiological Traits of Ornamental Shrubs. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, D.; Lebedeva, K.; Cherkashina, A.; Lebedev, V.; Tsereniuk, O.; Krygina, N. Study of Hybrid Modification with Humic Acids of Environmentally Safe Biodegradable Hydrogel Films Based on Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose. C 2022, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Akhzarmehr, A.; Chowdhury, S.D. Advancements in Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels: Sustainable Solutions across Industries. Gels 2024, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelo, R.C.; Fonseca, A.C.; Coelho, J.F.J.; Serra, A.C. A Sustainable Synthesis of Cellulose Hydrogels for Agriculture with Repurpose of Solvent as Fertilizer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, E.; Tatari, A.; Dehghani Firouzabadi, M. Effects of Biodegradation of Starch-Nanocellulose Films Incorporated with Black Tea Extract on Soil Quality. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmetullayeva, R.; Khavilkhairat, B.; Toktabayeva, A.; Mukhamadiyev, N.; Nurgaziyeva, E.; Abutalip, M. Biopolymer-Based Hydrogel Formulations for Improved Seed Coating Performance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Imran, S. Synthesis of Gum Tragacanth-Starch Hydrogels for Water Purification. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 8812–8825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Stendahl, J. Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Stoichiometry of Organic Matter in Swedish Forest Soils and Its Relationship with Climate, Tree Species, and Soil Texture. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modified Starch | Acrylic Acid | Total Corg | Corg in Modified Starch | K | P | N | Na | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| 15.77 | 37.36 | 25.73 | 7.52 | 20.76 | 6.30 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Localization | Classification USDA | % Sand | %Silt | %Clay | pHH2O | Corg [%] | Corg/Ntotal | Pt [μg/g] | RESP [μMCO2/g/24 h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dąbrowa | silt loam | 30 | 56 | 14 | 6.8 | 1.24 (0.01) | 9.9 | 446 | 2.35 |

| Pustki | silt loam | 4 | 82 | 14 | 6.3 | 1.63 (0.32) | 13.2 | 295 | 1.09 |

| Wagonowice | silt loam | 9 | 76 | 15 | 6.6 | 2.09 (0.07) | 9.8 | 612 | 0.55 |

| Brody | silt loam | 28 | 52 | 20 | 6.5 | 2.52 (0.12) | 10.0 | 718 | 1.38 |

| Strachocina1 | loam | 35 | 45 | 20 | 6.3 | 2.10 (0.26) | 9.5 | 749 | 0.93 |

| Strachocina 2 | silt | 9 | 83 | 8 | 6.5 | 4.19 (0.01) | 14.1 | 716 | 2.56 |

| Samples | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 8 | Day 36 | Day 46 | Day 51 | Day 78 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESP [μMCO2/g/24 h] | |||||||

| Soils (control) | 1.48 (0.81) a | 1.30 (0.81) | 1.18 (0.71) | 0.96 (0.53) | 0.81 (0.46) | 0.77 (0.45) | 0.69 (0.38) |

| Soils + PAA | 1.51(0.93) a | 1.36 (0.86) | 1.16 (0.61) | 0.96 (0.48) | 0.85 (0.45) | 0.78 (0.43) | 0.67 (0.38) |

| Soils+ SP1-g-PAA | 2.99 (0.75) b | 2.42 (0.52) | 1.45 (0.78) | 0.92 (0.47) | 0.88 (0.42) | 0.80 (0.37) | 0.70 (0.39) |

| Soils+ SP2-g-PAA | 2.91 (0.72) b | 2,37 (0.62) | 1.47 (0.71) | 0.95 (0.50) | 0.91 (0.44) | 0.82 (0.41) | 0.70 (0.38) |

| Samples | Pi [μg/g] | PT [μg/g] | Porg [μg/g] | Pmic Kp = 0.4 [μg/g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soils (control) | 60.84 (27.81) | 80.63 (23.68) | 21.18 (14.7) | 52.94 (36.5) |

| Soils + PAA | 60.87 (25.89) | 79.53 (22.67) | 20.71 (14.6) | 51.77 (36.5) |

| Soils+ ST1-g-PAA | 63.15 (28.01) | 82.30 (24.79) | 18.87 (9.01) | 47.17 (22.54) |

| Soils+ ST2-g-PAA | 64.62 (28.83) | 81.37 (23.6) | 22.23 (10.39) | 55.58 (25.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sroka, K.; Sroka, P. Soil Microbial Responses to Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid) Copolymers Addition. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031498

Sroka K, Sroka P. Soil Microbial Responses to Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid) Copolymers Addition. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031498

Chicago/Turabian StyleSroka, Katarzyna, and Paweł Sroka. 2026. "Soil Microbial Responses to Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid) Copolymers Addition" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031498

APA StyleSroka, K., & Sroka, P. (2026). Soil Microbial Responses to Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid) Copolymers Addition. Sustainability, 18(3), 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031498