1. Introduction

Earthquakes represent a highly destructive natural hazard, particularly in developing countries where a large proportion of the housing stock is constructed informally and lacks professional supervision [

1]. Non-engineered structures, often made of poorly confined or unreinforced masonry, significantly increase the risk of collapse and casualties during seismic events [

2,

3]. In Colombia, this challenge is especially pronounced, with estimates indicating that between 60% and 80% of residential buildings fall into this vulnerable category [

4]. The overlap between fragile construction and intense seismic exposure highlights the need for strategies that integrate technical improvements with community-based education to promote structural resilience [

5,

6]. Recent educational studies indicate that awareness-based interventions can reduce risk misperception by more than 30% among students in high-hazard regions [

7]. However, these gains predominantly reflect improved knowledge of appropriate behavioral responses during strong earthquakes, with limited evidence of enhanced understanding of underlying structural behavior or construction-related sources of vulnerability.

Seismic risk management has been framed primarily as a technical responsibility of professionals, such as engineers and architects, rather than as shared knowledge to be cultivated throughout society. This perspective overlooks that vulnerability is determined not only by structural design but also by informal knowledge, decision-making processes, and everyday construction practices within communities [

8]. Promoting earthquake awareness therefore means bringing seismic knowledge beyond professional circles to reach the broader community especially young people, who should grow into citizens capable of recognizing and valuing earthquake-resistant construction. According to [

9], even basic instruction in structural behavior and seismic response may significantly improve public awareness and preparedness. Experimental school-based interventions consistently report learning gains ranging from approximately 25% to 45% in core seismic concepts, such as earthquake generation, damage mechanisms, and basic protective actions. Nevertheless, most of these gains are associated with short-term conceptual recall, with limited emphasis on linking seismic phenomena to structural configurations and construction practices [

9,

10]. Furthermore, educational initiatives that translate complex engineering concepts into accessible and hands-on experiences have proven more effective than traditional learning methods in fostering long-term engagement and knowledge retention [

6,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Comparative analyses further indicate that experiential and interactive formats outperform lecture-based instruction by approximately 20% in retention and conceptual transfer metrics, particularly when learners are required to actively manipulate physical or visual representations of seismic behavior [

13]. Expanding access to seismic knowledge enables societies to enhance community capacity, promote safer construction practices, and encourage active participation in disaster risk reduction. This perspective is consistent with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, which emphasizes education and youth engagement in disaster preparedness [

14].

Effective dissemination of seismic knowledge requires pedagogical strategies that actively engage students and promote lasting changes in attitudes and practices. Active learning has proven particularly effective in this regard, as it broadens access to knowledge by involving students directly in the learning process [

15]. These experiences bridge academic concepts and real-world contexts, allowing participants to build understanding through hands-on experimentation and problem solving. Innovative approaches such as shake tables, interactive learning tools, collaborative building tasks, problem-based learning, and game-based strategies facilitate the teaching of seismic design and structural behavior while also improving disaster preparedness [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Game-based seismic education studies report increases in student engagement exceeding 40% compared to conventional classroom activities; however, many of these approaches prioritize motivation and participation over systematic assessment of conceptual understanding or structural reasoning [

20]. While some of these approaches were initially developed in university contexts, others were implemented in K-12 education, such as instructional shake table activities adapted for school audiences [

9,

10,

16,

22,

23]. Similarly, recent studies highlight the potential of 3D printing as an innovative tool to enhance the teaching of structural dynamics and structural analysis [

24,

25]. Notably, even kindergarten-level disaster education programs demonstrate measurable improvements in preparedness and risk awareness despite minimal technical content, reinforcing the value of early intervention while also highlighting the challenge of progressively introducing more complex concepts such as structural behavior and seismic design principles [

26]. Additional research indicates that integrating earthquake-resistant design principles into early education fosters key STEM skills, including critical thinking and teamwork [

22,

26]. Evidence from Latin American K-12 studies further supports the effectiveness of school-based seismic education in high-risk regions, such as Chile and Mexico [

7,

27]. In the context of Mexico City, prevention-oriented curricula have increased correct risk identification responses by more than 35%. However, these interventions largely focus on emergency response and hazard recognition rather than on understanding why certain buildings perform poorly during earthquakes [

27]. Moreover, school-based protocols developed under the KnowRISK project, combining direct scientist–student interaction, flipped learning, and situated learning activities, demonstrate that structured seismic education effectively enhances students’ awareness and preparedness [

23]. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of integrating seismic risk education into curricula, particularly in regions that are vulnerable to seismic hazards.

Despite recent advances in seismic risk education, limited evidence exists on how experiential, low-cost learning programs influence conceptual understanding of seismic behavior among young people in developing countries. Current debates in seismic education emphasize the need for educational models that are simultaneously scalable, low-cost, and empirically validated, while moving beyond awareness-based outcomes toward measurable gains in conceptual understanding of seismic behavior and structural vulnerability [

6,

9]. This paper presents the design, implementation, and evaluation of the Learning Experience for Earthquake Awareness Program (LEAP), an educational initiative developed to address this gap by connecting technical construction knowledge with community-level understanding. LEAP employs a participatory methodology that integrates theoretical concepts with hands-on activities, enabling students to explore seismic design fundamentals through experimentation and direct observation of structural behavior under simulated earthquakes. Unlike immersive digital or simulation-heavy approaches that often require specialized infrastructure, LEAP deliberately prioritizes physical interaction, simple materials, and face-to-face collaboration to ensure accessibility and replicability in resource-constrained educational environments. The program was implemented in three schools and two universities across different Colombian cities and incorporated tangible tools such as scaled structural models, shaking tables, and collaborative building tasks. Its effectiveness was assessed using pre- and post-surveys that measured changes in participants’ conceptual knowledge and practical understanding of seismic risk. The novelty of this work lies in translating fundamental principles of structural mechanics and seismic response into playful, accessible learning experiences for students without prior engineering background. By situating its design and evaluation within empirical trends reported in recent educational seismology research, LEAP contributes quantitative evidence from an underrepresented Latin American context, addressing a recognized gap in the literature regarding low-cost, experiential seismic education in developing countries. Unlike traditional approaches centered on professional training or regulatory measures, LEAP demonstrates that a culture of earthquake resilience can be fostered early by empowering young people, regardless of their future careers, to recognize, value, and advocate for responsible construction practices.

2. Design and Implementation

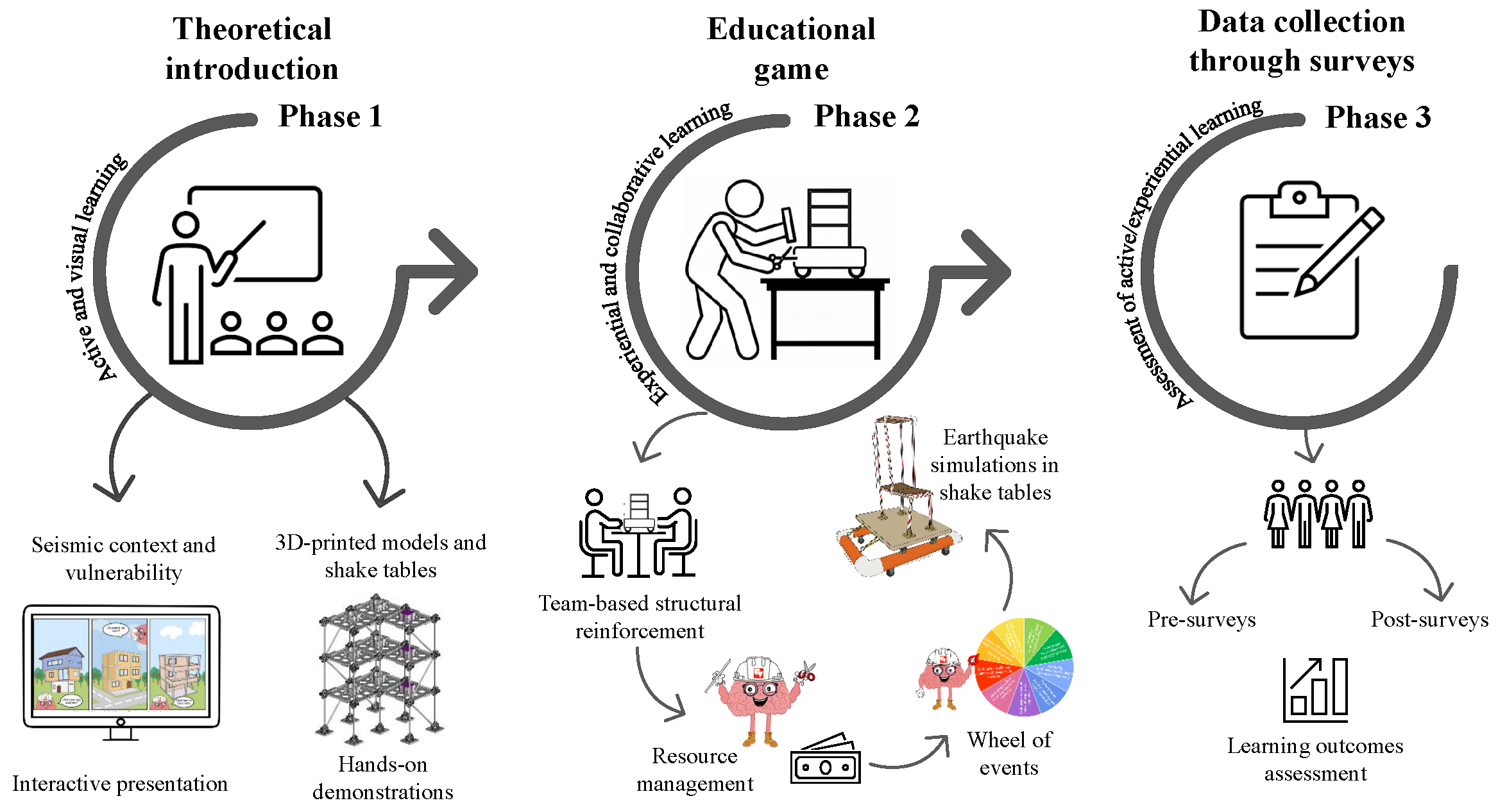

The LEAP methodology was developed to translate complex seismic and structural concepts into accessible learning experiences for young students. The program integrates principles of experiential and inquiry-based learning, emphasizing active participation, collaboration, and reflection. LEAP comprises three sequential phases: a theoretical introduction, an educational game, and a survey-based evaluation of learning outcomes (

Figure 1). The program was implemented with 141 students from schools located in seismically active regions. Young students were selected through a convenience sampling approach, based on the availability of partner schools. The sample included participants aged 14–18, comprising secondary school students and first- and second-year university students enrolled in engineering, construction, and architecture programs. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and participants provided assent, with ethical approval granted by the Universidad del Valle Institutional Review Board.

Before implementing the activity in schools, pilot sessions were conducted to calibrate the duration of each phase, determine the optimal quantity of construction materials, and assess how each event affected structural stability. These preliminary trials showed the need to assign specific time slots for purchasing and assembling structural elements to maintain the game’s dynamism and ensure continuous participant engagement. The number of columns and slabs was likewise adjusted to ensure that the models were sufficiently tall for seismic effects to be clearly visible. The following subsections describe the methodological strategies applied in each phase of the program.

2.1. Theoretical Introduction

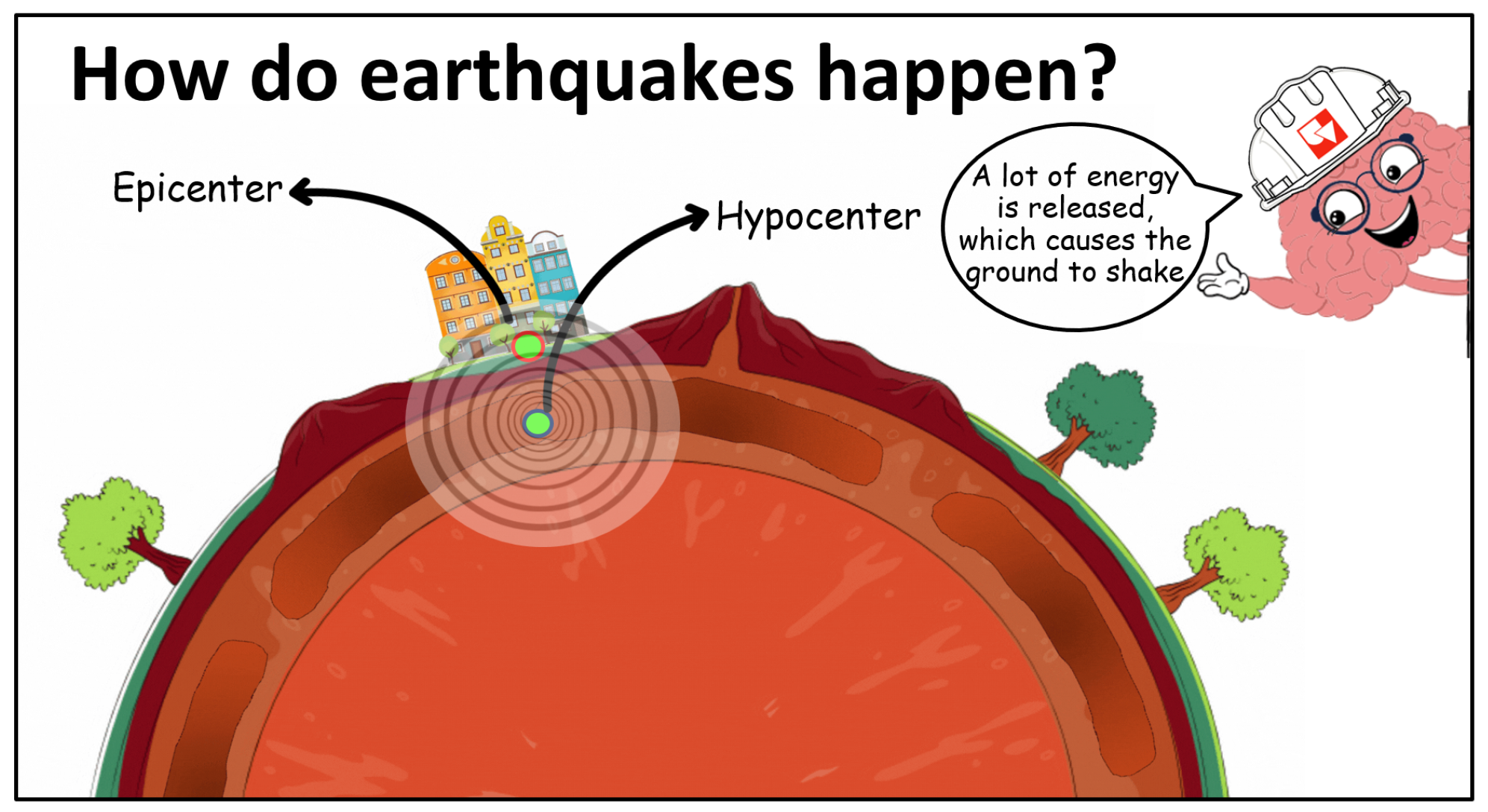

Each session starts with a ten-minute theoretical overview supported by an interactive presentation. The visual material is designed to explain concepts clearly and concisely, using cartoon-style illustrations to sustain attention and enhance understanding. A distinctive pedagogical element, a brain wearing a construction helmet, appears throughout the LEAP activities as a symbolic reminder of awareness and safety in construction practices. The presentation opens with a brief review of Colombia’s seismic history to increase participants’ understanding of earthquake recurrence and impact in the country. It then introduces the process of seismic generation, covering the concepts of hypocenter, epicenter, and magnitude as the foundation for understanding earthquake dynamics (

Figure 2).

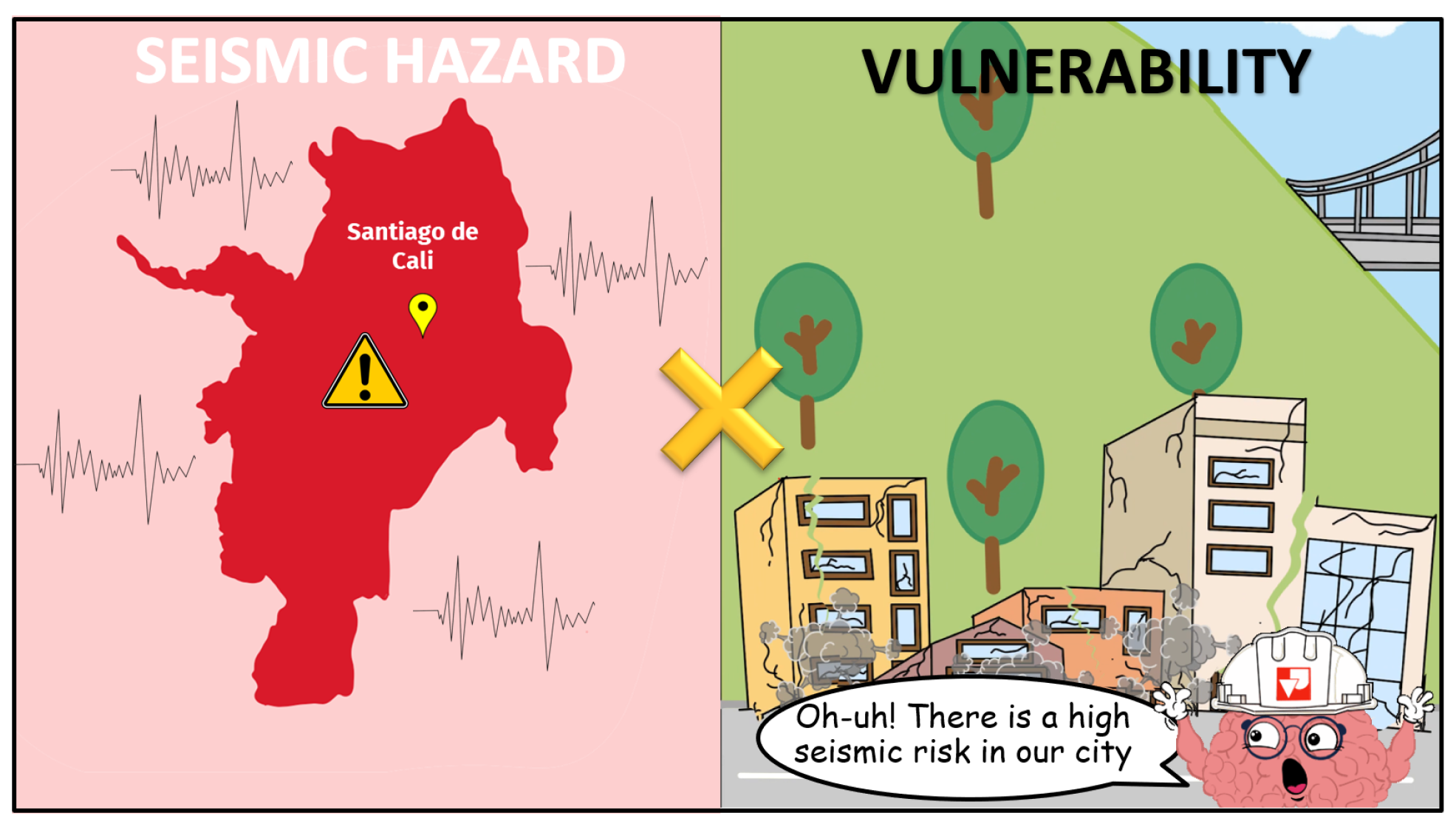

Next, the tectonic context of Colombia within the Pacific Ring of Fire is presented, emphasizing the collision and subduction of tectonic plates that explain the country’s high seismicity. As an illustrative case, a high-hazard region is examined where proximity to active geological faults, combined with the widespread presence of non-engineered construction, increases seismic risk (

Figure 3).

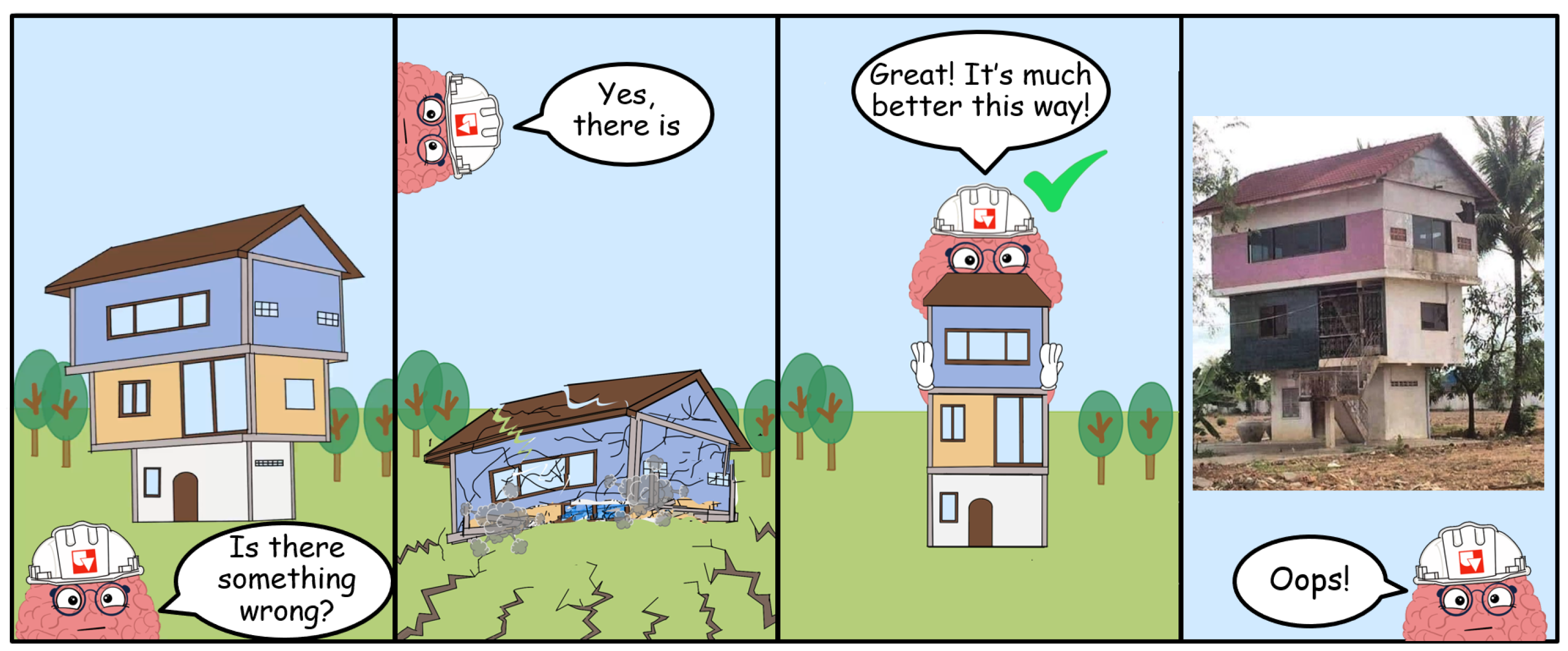

Finally, to highlight the importance of earthquake-resistant construction, cartoon depictions of non-compliant buildings are compared with photographs of real structures. This visual strategy translates abstract concepts into familiar images, connecting instruction to students’ everyday environments. Research demonstrates that such contextualized visual comparisons enhance conceptual understanding and facilitate the transfer of knowledge to real situations [

28]. Through this activity, students identify common structural weaknesses and reflect on the potential consequences of these deficiencies during an earthquake (

Figure 4).

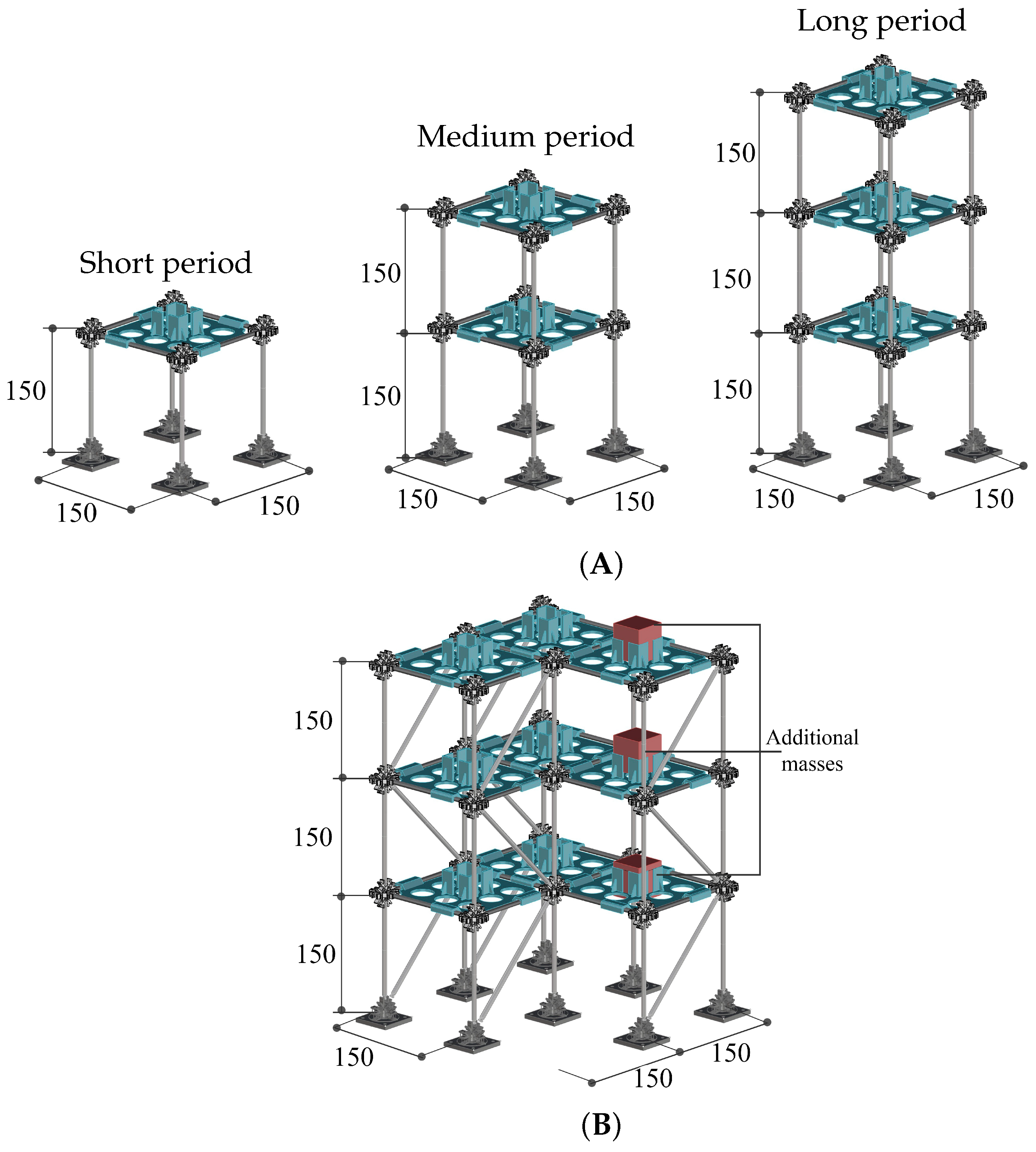

The interactive presentation is complemented by hands-on demonstrations that allow participants to observe key seismic concepts in practice. Two demonstrations are conducted using 3D-printed models made of PLA (Polylactic Acid) filament. In the first, three structures of different heights are subjected to base motions with varying excitation periods, illustrating the phenomenon of resonance: taller structures are more responsive to long-period excitation, whereas shorter ones are more affected by short-period excitation (

Figure 5A). In the second demonstration, an L-shaped building model with a re-entrant corner is tested. An asymmetric mass distribution was introduced by adding a 300 g mass to one side of the structure at each floor, as shown in (

Figure 5B). The resulting torsional response highlights the importance of balanced mass and stiffness distribution in earthquake-resistant design. These demonstrations transform abstract seismic concepts into observable structural behavior, helping participants understand why non-engineered construction is particularly vulnerable to earthquakes and how appropriate design can mitigate these risks.

Base motions required for these observations are generated using manually operated shaking tables. Each table consists of a lightweight plastic pipe frame supporting a wooden platform mounted on low-friction wheels, enabling horizontal motion to be manually applied by participants and facilitators. As the devices do not incorporate a motorized system, no fixed excitation frequency or amplitude can be specified. Instead, the characteristics of the input motion depend on the speed of the manual excitation, allowing participants to associate faster base movement with higher-frequency excitation and slower movement with lower-frequency excitation. This qualitative lateral input is sufficient to illustrate comparative structural responses, including resonance tendencies, torsional behavior, soft-story mechanisms, and stability variations associated with irregular or poorly configured structural systems.

2.2. Educational Game

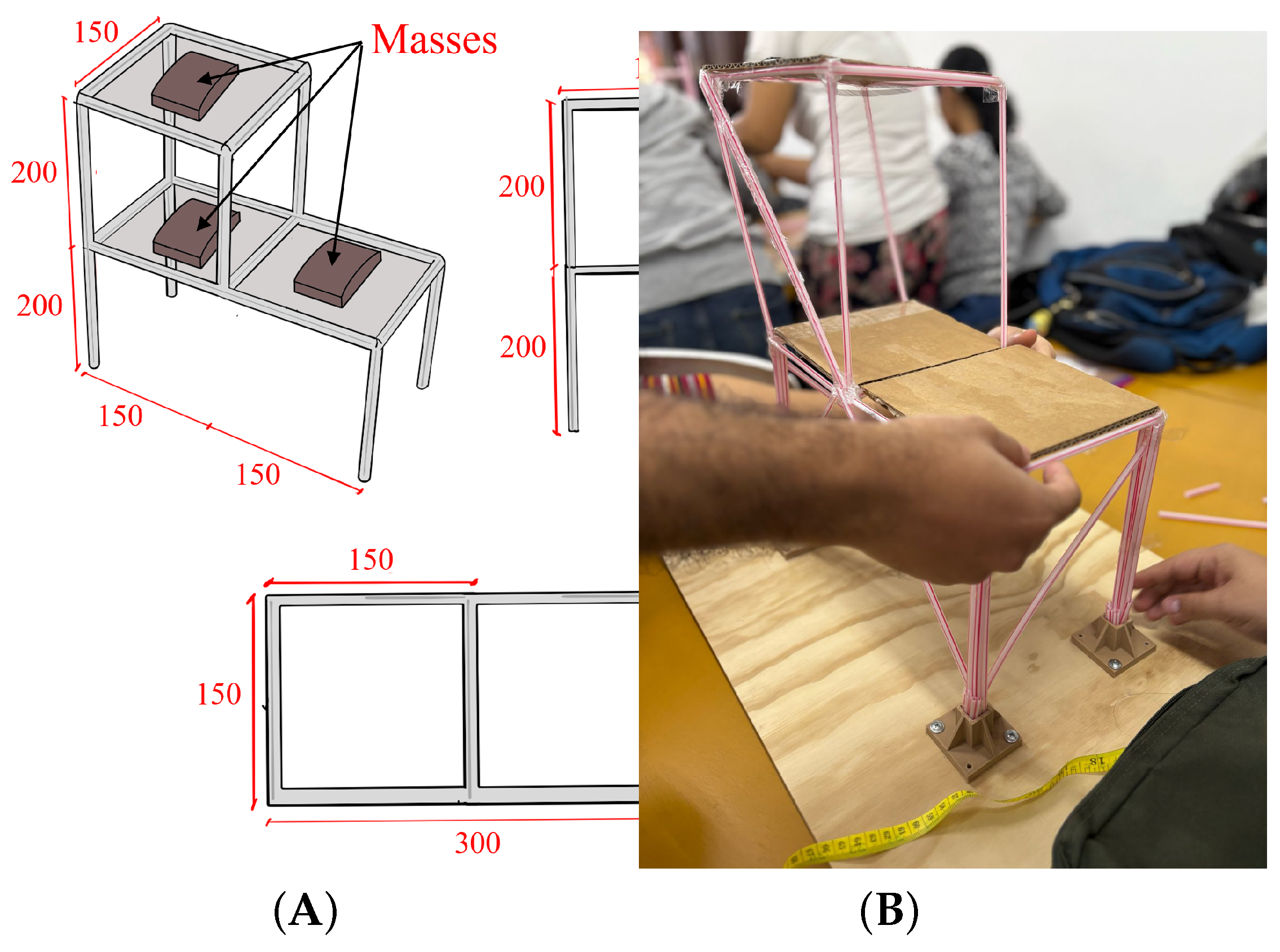

The educational game enables participants to apply theoretical concepts by addressing structural issues commonly found in non-engineered buildings. These include vertical irregularities, such as torsion and soft stories, and construction weaknesses, such as inadequate connections. Participants work in teams of five to seven to reinforce a model structure intentionally designed with a vertical geometric irregularity. The initial configuration consists of one drinking-straw column per vertical element (5 mm in diameter), three cardboard floor slabs (4 mm thick), and three distributed masses of 150 g. Each team receives 60 additional straws for reinforcement and transparent adhesive tape (12 mm thick) to assemble and strengthen the joint connections. The structure is anchored to a 3D-printed foundation composed of a 50 × 50 mm base plate with four 4 mm anchoring perforations and a reinforced 20 × 20 mm central socket. This system is mounted on a 450 × 550 mm platform, on which the model is connected. All structural dimensions and geometric details of the initial setup are shown in (

Figure 6A). The objective is to strengthen the model to support the three distributed masses on the floor slabs and withstand base motions simulating earthquake excitation. This predefined irregularity presents a tangible engineering challenge that encourages participants to identify weaknesses, propose solutions, and collaboratively design structural reinforcements.

Figure 6B illustrates the physical model constructed according to the configuration shown in

Figure 6A.

The activity incorporates a strategic component through financial resource management. Each team receives an initial budget (US $25) to purchase construction materials from a designated store within the activity. The store provides a selection of low-cost materials that participants can use to repair, strengthen, or improve their model structures, including straws (US $2 each), cardboard walls measuring 200 × 150 mm (US $10), and tape segments of 150 mm (US $4), as well as additional services such as removing a mass (US $5) or repairing a column (US $8). This setup encourages students to plan carefully, prioritize expenses, and experience the challenges of managing limited resources, as is often the case in real construction projects. The dynamism and engagement of the activity are enhanced through the incorporation of a “wheel of events’’. This mechanism introduces unexpected scenarios that teams must address during the design, construction, and testing stages. The selected events are intended to represent, in a controlled and pedagogical manner, conditions that may occur during seismic action or a structure’s service life. The wheel is activated over three consecutive rounds, and each team spins it once per round. Although the same five event types are available in every round, their selection probabilities are intentionally non-uniform. During the first two rounds, events associated with structural damage are more likely to occur, emphasizing the initial vulnerability of the models. In the final round, earthquake-related events are assigned a higher probability to highlight seismic performance at the conclusion of the activity. Each event is applied immediately after selection, regardless of the construction progress of individual teams, ensuring comparable conditions across groups. The inclusion of these events reinforces adaptive decision-making, preventive design strategies, and critical assessment under evolving constraints. Upon spinning the wheel, teams may encounter one of the following events:

- (a)

Random financial bonus: A team that receives an additional monetary allocation may use the funds to acquire further materials, allowing them to strengthen or modify their structures. This event highlights the role of financial planning and resource optimization in construction management.

- (b)

Unexpected additional load: A team is permitted to place supplemental mass on the structure, simulating real-world phenomena such as the accumulation of furnishings or the installation of heavy equipment. This scenario demonstrates how unanticipated loads can modify a structure’s dynamic behavior and influence its overall stability.

- (c)

Moderate earthquake simulation: The structure is exposed to ground motions representative of a moderate seismic event. This test enables participants to observe their models’ responses under low-to-medium seismic demands and to identify early indicators of potential instability.

- (d)

Design-level earthquake simulation: The structure is subjected to motions consistent with a design-level earthquake. Through this scenario, participants assess their models’ capacity to withstand severe seismic loads and gain insight into the principles of earthquake-resistant design.

- (e)

Simulated structural damage: One column is deliberately removed from a team’s structure to replicate the loss of a critical element. This event illustrates the importance of redundancy, robustness, and alternative load paths in structural systems.

It is important to note that the “moderate-level” and “design-level” earthquake simulations do not correspond to quantified seismic parameters, such as PGA or spectral acceleration, since the shaking tables are manually operated and do not reproduce calibrated ground motions. A consistent protocol was followed to ensure inter-session stability. Moderate-level trials lasted approximately five seconds and involved low-amplitude shaking cycles. Design-level trials lasted approximately fifteen seconds and involved higher-amplitude. Specific LEAP team members applied each motion type to maintain consistency across all sessions. Instead, these categories represent qualitative instructional scenarios designed to illustrate increasing levels of structural demand rather than code-defined seismic intensities. These events introduce variability and uncertainty into the activity, requiring teams to make real-time decisions under changing conditions. By simulating practical challenges faced in construction and seismic design, they encourage critical thinking, teamwork, and problem-solving while reinforcing the importance of adaptability and preventive planning in structural engineering.

Once all components of the activity are prepared, the game proceeds as a competition among teams, structured in several stages. First, teams are formed and provided with their initial materials and financial resources. Participants organize themselves in the classroom and, within a set time limit, reinforce their structures using their own design strategies. Throughout the game, teams interact with the store at specific moments to purchase materials and make financial decisions. Progressive challenges introduced through the wheel of fortune increase both the difficulty and engagement of the exercise. Finally, a design-level earthquake test is conducted to evaluate the stability of the constructed models. The team whose structure remains standing after all challenges is declared the winner, highlighting how the competition format increases engagement within the activity. This final evaluation is performed using the manually operated shaking tables described in

Section 2.2, ensuring consistency in the simulated seismic excitation applied throughout the activity. This format supports teamwork, problem-solving, and critical reflection on construction practices under seismic risk.

Beyond conceptual learning, the game also fosters transferable soft skills such as teamwork, negotiation, and adaptive problem-solving, which are essential competencies in engineering education. By recreating realistic decision-making contexts, LEAP provides participants with opportunities to practice collaboration and respond constructively to uncertainty. This experience reinforces the social and professional dimensions of seismic risk management and highlights the importance of collective responsibility in addressing structural safety challenges.

2.3. Data Collection Through Surveys

A total of 141 students participated in the six LEAP sessions carried out in secondary schools and universities located in seismically active regions. The sample included secondary school students in grades 8 to 11, as well as first- and second-year university students enrolled in engineering, architecture, and construction programs. Participant ages ranged from 14 to 18 years, with group sizes varying between 13 and 47 students per session, as shown in

Table 1.

A structured questionnaire was used to assess students’ perceptions and understanding of seismic and structural concepts. Pre- and post-surveys (

Table 2) enabled the identification of prior knowledge, interests, and expectations and the evaluation of the program’s impact. The instrument includes multiple-choice items organized on a five-point Likert scale, where one (1) represents the lowest level of agreement or familiarity (e.g., strongly disagree or not familiar at all) and five (5) the highest (e.g., strongly agree or very familiar). To ensure comparability, both the pre- and post-surveys contain the same questions. The post-survey, however, includes the additional instruction “according to what was learned in the LEAP,…” ensuring that responses reflect the knowledge acquired during the activity. The questionnaires were administered in paper format in schools and in digital format in universities to facilitate data collection. Complementary qualitative classroom observations are conducted to enrich the quantitative data and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the educational outcomes. Anonymity was guaranteed, no sensitive personal data were collected, and participation was voluntary, with the option to omit any question.

Table 2.

Questionnaire on knowledge and perceptions related to earthquakes and structural vulnerability (five-point Likert scale: 1 = lowest; 5 = highest).

Table 2.

Questionnaire on knowledge and perceptions related to earthquakes and structural vulnerability (five-point Likert scale: 1 = lowest; 5 = highest).

| No. | Question |

|---|

| | Conceptual |

| 1 | How much do you agree with the statement that earthquakes are sudden and strong ground movements caused by the release of energy along cracks in the Earth’s crust? |

| 2 | How familiar are you with the difference between the focus (or hypocenter) and the epicenter of an earthquake? |

| 3 | How well do you understand what seismic magnitude means when you hear that a magnitude 5 earthquake has occurred? |

| 4 | How much do you think the intensity of an earthquake affects the damage caused to people and buildings? |

| 5 | How much do you think poor-quality materials or lack of maintenance make a building more likely to be damaged in an earthquake? |

| | Visual |

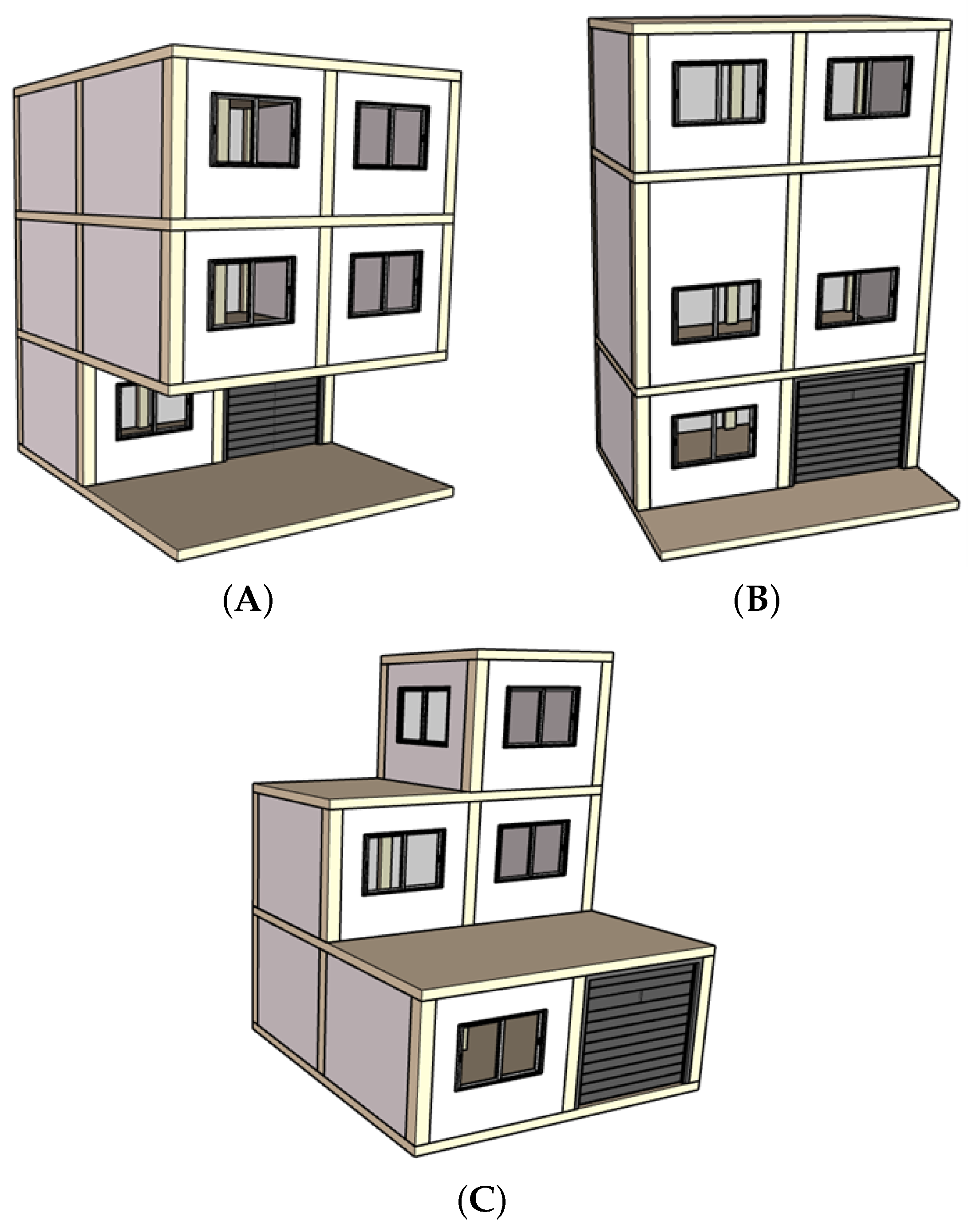

| 6 | Do you think the building shown in the image is vulnerable to earthquakes? (Figure 7A shows a building with an interruption of vertical-resisting elements.) |

| 7 | Do you think the building shown in the image is vulnerable to earthquakes? (Figure 7B shows a building with a soft story.) |

| 8 | Do you think the building shown in the image is vulnerable to earthquakes? (Figure 7C shows a building with vertical geometric irregularity.) |

| | Perception |

| 9 | How possible do you think it is to build a house or building that can resist earthquakes? |

| 10 | How vulnerable do you think your home (or building) is to earthquakes? |

The images used in the questionnaire were standardized based on the configurations of structural irregularities defined by the Colombian seismic design code (NSR-10) [

29], ensuring conceptually consistent and methodologically appropriate visual stimuli for all participants.

The internal validity and reliability of the questionnaire were established through an expert review process. Three specialists in structural engineering and science education evaluated the instruments to ensure content relevance and clarity.A pilot application was then conducted with a group of 20 students to identify potential ambiguities and refine the wording of the questions.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the LEAP implementation, focusing on changes in participants’ knowledge and awareness. It reports pre- and post-intervention survey outcomes and analyzes general trends across study groups, providing an overview of the program’s educational impact by academic level. The Likert scale used in this study yields ordinal data; therefore, its analysis should be based on conceptually stable categories rather than on artificial numerical differences, as noted by [

30]. Because the objective of the LEAP program is to determine whether participants achieve a sufficient level of understanding or recognition rather than to examine fine-grained response variations, a clear achievement threshold was defined by grouping response options 4 and 5. As a robustness check, analyses were replicated using the full ordinal Likert scale. This form of recategorization is methodologically appropriate for educational evaluations focused on basic competencies, where constructs can be meaningfully represented as qualitative states of “achievement” versus “non-achievement” [

31,

32]. Furthermore, the use of dichotomous indicators improves the interpretability of results for non-specialist audiences and facilitates the communication of the educational impact of the intervention, which is a central concern in evidence-based learning research [

15]. In this study, it was used to quantify improvements in seismic knowledge and awareness, providing a precise measure of the LEAP’s educational effectiveness. Detailed ordinal descriptives and robustness analyses are provided in the section

Appendix A.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to compare paired responses before and after the LEAP intervention. This non-parametric test evaluates differences between two related samples by analyzing the ranks of paired differences [

33], and it has been widely used in studies of educational interventions [

34,

35,

36]. The test was selected because the survey data were ordinal and did not follow a normal distribution. Results were reported using the

p-value, with statistical significance defined as

p < 0.05. In addition, the effect size was estimated using

r to quantify the magnitude of the observed changes, with values of

r ≈ 0.10 interpreted as small effects, ≈0.30 as moderate effects, and ≥0.50 as large effects. Finally, the internal consistency of the instrument was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, where values ≥ 0.70 indicate acceptable reliability, values ≥ 0.80 indicate good reliability, and values ≥ 0.90 indicate excellent reliability, ensuring the robustness of the measurement instrument.

For analysis, three study groups were defined. Group 1 included all 141 participants across the six sessions. Group 2 consisted of 80 secondary school students, representing the lowest academic level among participants. Group 3 comprised 61 university students in the second to fourth semesters, representing the highest academic level within their respective disciplines. The analysis of pre- and post-surveys administered to the three participant groups in the LEAP reveals consistent improvements in seismic knowledge and awareness.

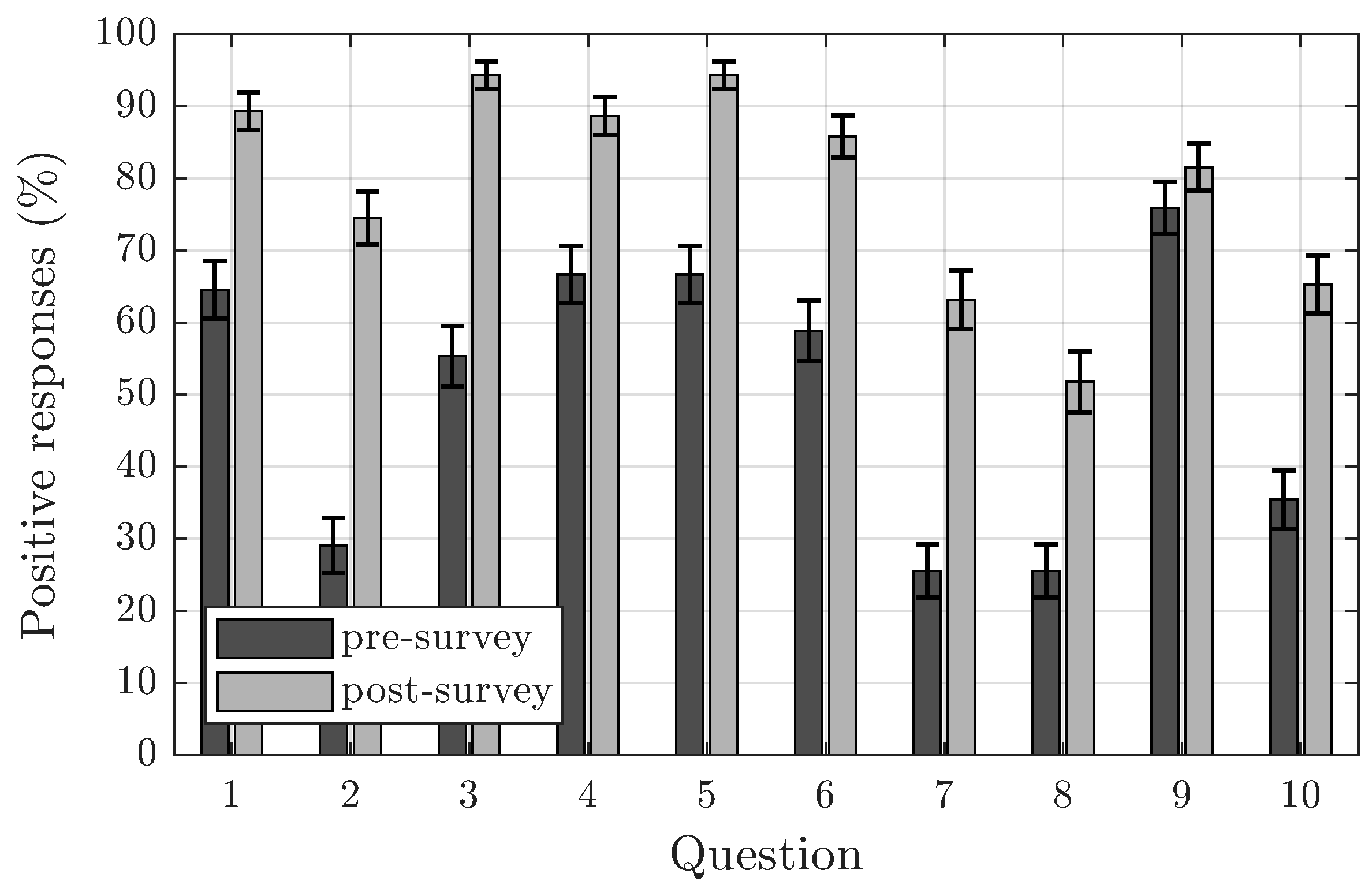

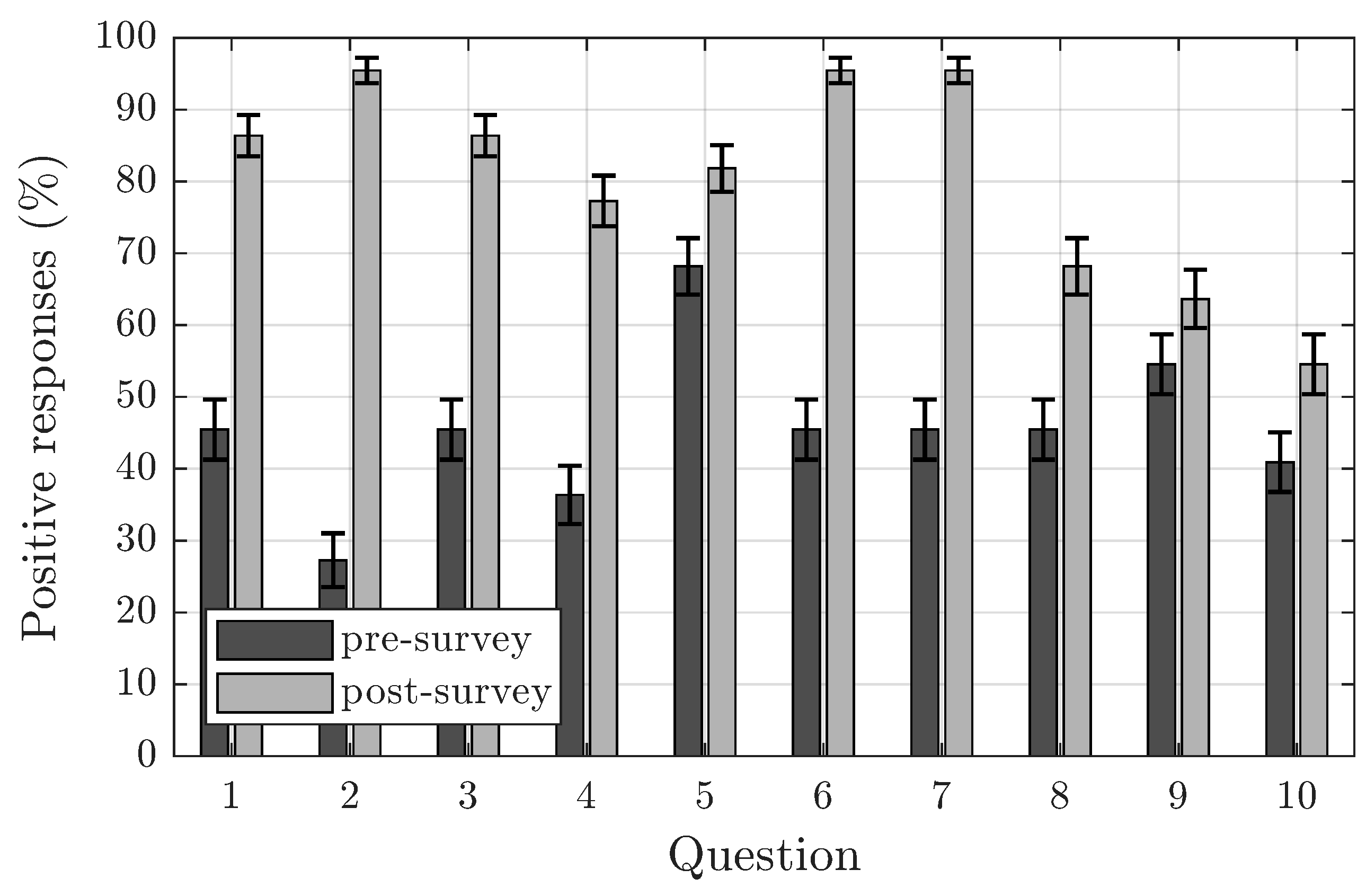

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

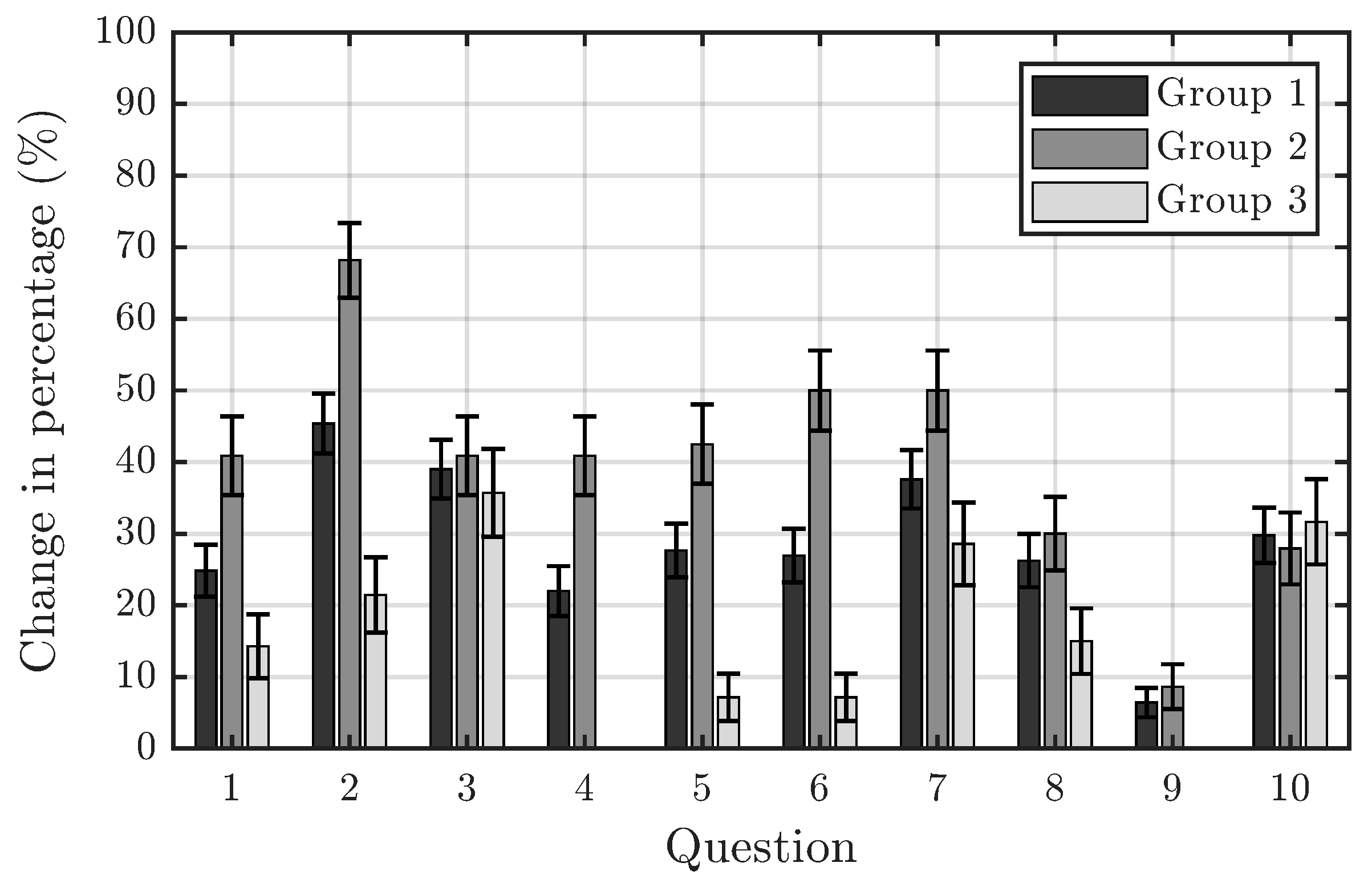

Figure 10 present the change in the percentage of positive responses before and after the LEAP, while

Figure 11 summarizes the overall percentage change observed across the three groups. The following paragraphs describe these results in more detail for each group.

For Group 1, which included all 141 LEAP participants, the results indicate statistically significant improvements in the understanding of key concepts addressed during the sessions (

Figure 8). The most notable learning gain was observed in Question 2, which assessed the distinction between the hypocenter and the epicenter of an earthquake. Positive responses increased from approximately 29% to over 75% (a 45.39% gain;

p =

), with a large effect size (

), demonstrating a clearer understanding of this fundamental concept. Question 3, related to seismic magnitude, also showed a substantial improvement of 39.01% (from 55% to 94%), associated with a large effect size (

), while Question 7, which examined the perception of seismic vulnerability in a soft-story building, recorded a 38% increase with a moderate-to-large effect size (

). Together, these results demonstrate substantial progress in both conceptual knowledge and the ability to visually identify structural vulnerabilities developed through the LEAP activities.

Questions 6, 7, and 8, which examined construction-related factors affecting a building’s seismic performance, showed increases in positive responses ranging from 25% to 38%. These changes were statistically significant and exhibited moderate to large effect sizes (

), indicating that the visual materials and structural illustrations used during the LEAP effectively enhanced participants’ understanding of how design irregularities influence seismic behavior. The smallest change was observed in Question 9, related to the perceived feasibility of constructing earthquake-resistant buildings. Positive responses rose modestly by 5.67% (from 75.89% to 81.56%;

p =

), with a small effect size (

), suggesting a ceiling effect due to high pre-survey agreement rather than limited instructional impact. Finally, Question 10, which assessed awareness of the seismic vulnerability of one’s own home, showed a 29.79% increase in positive responses with a moderate effect size (

), reflecting greater understanding of local seismic risk following the learning experience. The internal consistency of the questionnaire for Group 1 was acceptable (Cronbach’s

pre and

post), supporting the reliability of the observed trends. Although the post-test

value was slightly below the conventional threshold of 0.70, this level of reliability is considered adequate for exploratory educational research and for instruments assessing multiple related constructs [

37]. Moreover, decreases in Cronbach’s

following educational interventions have been documented, as increased conceptual differentiation among participants may lead to greater response variability and reduced inter-item correlations [

38]. In this context, the moderate post-test

likely reflects enhanced understanding rather than measurement inadequacy, indicating that the questionnaire remained suitable for detecting changes in knowledge and seismic risk perception induced by the learning experience.

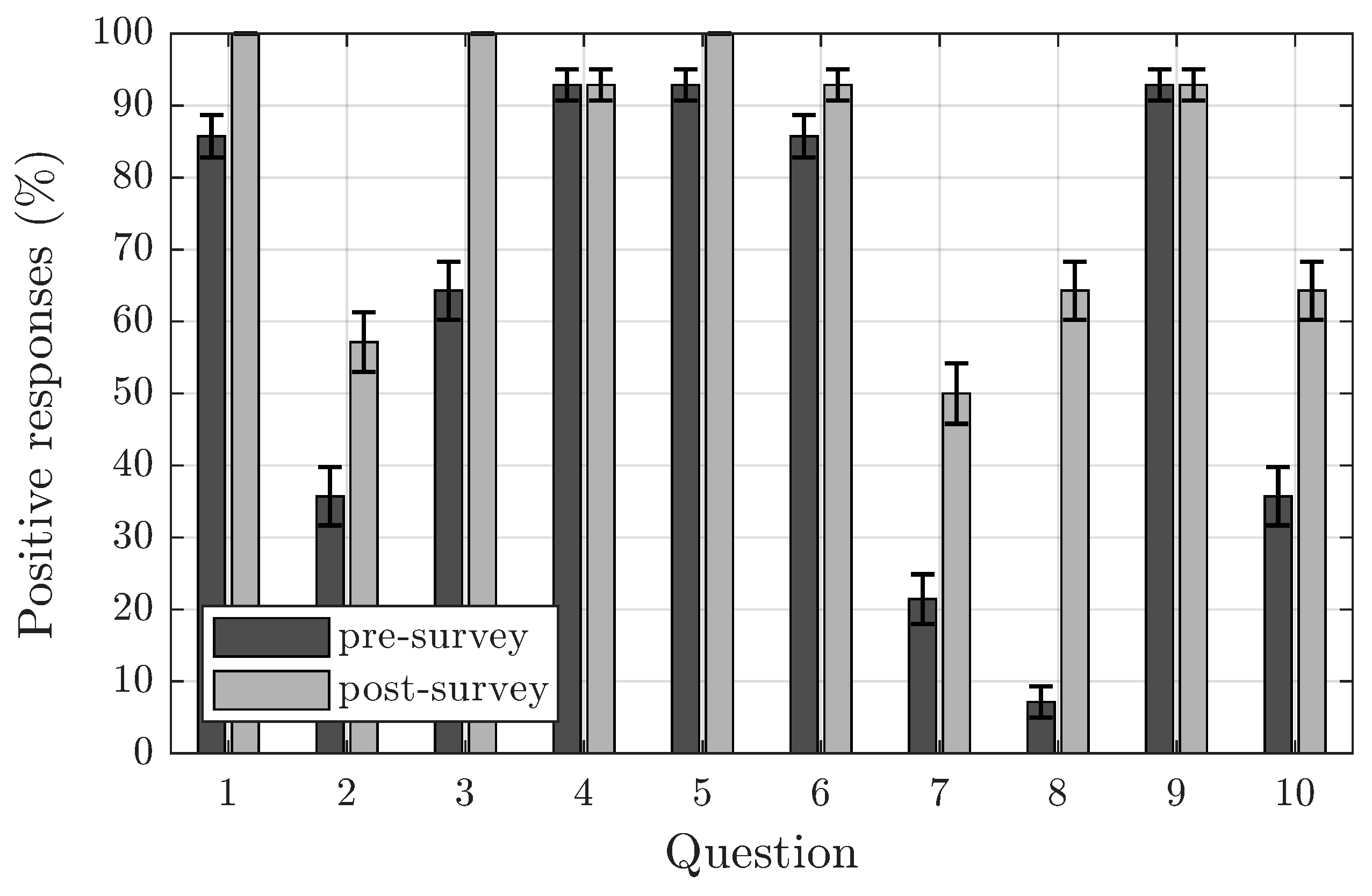

For Group 2, composed of 80 eighth-grade students identified as having the lowest academic level among LEAP participants, the results show statistically significant improvements in understanding the key concepts addressed during the LEAP sessions (

Figure 9). The most substantial learning gain occurred in Question 2, which assessed familiarity with the difference between the hypocenter and the epicenter. Positive responses increased from 27.27% to 95.45% (a 68.18% gain;

p =

), accompanied by a large effect size (

), indicating a much clearer comprehension of this fundamental concept. Questions 3 and 4, related to seismic magnitude and the relationship between intensity and damage, each showed 40.91% increases in positive responses (

p =

and

p =

, respectively), both associated with large effect sizes (

–

), suggesting that students strengthened their conceptual understanding of earthquake behavior.

Questions 6 and 7, which involved identifying structural vulnerabilities in visual examples of soft-story and vertically irregular buildings, showed 50% increases in positive responses, both of which were statistically significant (p < ) and associated with large effect sizes (). These results demonstrate improved recognition of structural configurations associated with higher seismic risk. In contrast, Question 5, addressing the role of construction materials and maintenance in seismic vulnerability, showed a more modest improvement of 13.64% (p = ), with a moderate effect size (). Finally, Question 9, concerning the feasibility of constructing earthquake-resistant buildings, was the only item without a statistically significant change (p = ), with a small effect size (), suggesting that perceptions were already partially formed before the intervention. The questionnaire demonstrated acceptable reliability for this group (Cronbach’s pre and post).

The results for Group 3, composed of 61 university students from the second to fourth semesters of Civil Engineering, Architecture, and Construction programs, show a generally positive trend in the assimilation of LEAP content, though with variations in the magnitude and statistical significance of the gains (

Figure 10). Despite having the highest academic background among participants, the LEAP sessions reinforced key concepts related to seismic risk and structural vulnerability identification. The most notable improvement occurred in Question 8, which assessed perceptions of vulnerability in a building with vertical irregularity. Positive responses increased from 7.14% to 64.29% (a 57.14% gain;

p =

), with a very large effect size (

), indicating a marked improvement in recognizing unfavorable structural configurations. Similarly, Question 3, focused on seismic magnitude, showed a 35.71% increase (from 64.29% to 100%;

p =

), also associated with a very large effect size (

), reflecting the consolidation of fundamental technical knowledge.

Moderate, though non-significant, improvements were observed in Question 2 (difference between epicenter and hypocenter) and Question 7 (soft-story vulnerability), with increases of 21.43% and 28.57%, respectively. These limited changes are consistent with small to moderate effect sizes and high baseline knowledge levels. Questions 6 and 9 showed no change (92.86% in both pre- and post-surveys), likely because knowledge was already acquired through prior coursework. Similarly, Questions 4 and 5 displayed high baseline values, limiting the potential for additional gains. The internal consistency of the questionnaire for Group 3 remained acceptable (Cronbach’s pre and post). Overall, these findings suggest that for students with advanced academic training, the LEAP primarily reinforced existing knowledge while deepening understanding of less-emphasized or visually oriented concepts.

Figure 11 presents the percentage change in positive responses across the three study groups. The results provide a comparative overview of learning gains associated with the LEAP intervention. Group 1 includes all 141 participants and serves as an overall reference for program effectiveness. This group shows consistent positive gains across all questionnaire items. These results indicate an overall improvement in seismic knowledge and risk awareness. Groups 2 and 3 are subsets of Group 1 and are analyzed separately according to academic level. Group 2, composed of secondary school students, exhibits the largest percentage gains. The greatest improvements appear in questions addressing epicenter–hypocenter differences and seismic magnitude. These results indicate substantial conceptual learning among students with limited prior knowledge of seismic phenomena. Group 3 shows more moderate gains across most questionnaire items. Smaller changes are observed in topics already addressed in academic coursework. No percentage change appears in Questions 4 and 9, indicating strong prior knowledge. Clear improvements are observed in visually supported items, particularly Question 8. These results indicate effective reinforcement of applied and visual understanding. Overall, the findings demonstrate that LEAP is effective across different educational levels. Younger students achieve greater conceptual gains, while advanced participants strengthen applied seismic understanding. Results were consistent with the ordinal analyses, indicating conclusions do not depend on dichotomization.

Across all groups, Question 9 consistently showed the least variation, reinforcing the interpretation that the feasibility of safe construction was a pre-existing belief rather than a concept newly acquired through the sessions. Conversely, Question 10, which addressed participants’ perceived vulnerability of their own homes, showed consistent improvement across groups, reflecting heightened personal awareness of local seismic risk following the learning experience.

From a pedagogical design perspective, LEAP incorporates early visual and physical scaffolds enabling rapid recognition of structural and relational vulnerabilities. Learning tasks are intentionally staged to support the gradual development of temporal and causal reasoning beyond immediate visual cues. Learning emerges through iterative feedback loops linking student inquiry actions, observable shake-table responses, and targeted teacher facilitation. This design prioritizes fast engagement and structural recognition, while deeper causal understanding matures more slowly over extended learning horizons.

This study presents some limitations. The sample was non-random and convenience-based, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The evaluation relied on self-reported measures and was administered immediately after the activity, preventing any assessment of long-term learning retention. Moreover, the absence of a control group substantially limits the ability to draw causal inferences regarding the specific impact of the LEAP intervention.

The results of LEAP highlight the need for a clear operational framework supporting flexible implementation in resource-limited educational settings. Replicability can be ensured by using low-cost, readily available materials and standardized learning activities. Structural models may use wooden sticks or pencils for columns and recycled cardboard for slabs. Mass elements can be represented using sand or modeling clay. Seismic simulation can be achieved using simple manual devices built from boxes or sliding surfaces. Using this configuration, approximate material costs per session ranged between USD 20 and 40, depending on group size. Session setup required about 20–30 min, while instructional activities lasted approximately 90 min. These materials preserve core learning objectives while minimizing infrastructure and equipment requirements.

Integration into formal curricula can be achieved through modular activities within physics, technology, or STEM-related courses. LEAP can also be incorporated into disaster risk reduction or civil protection education programs. Scalability is supported by the program’s standardized structure and limited logistical requirements. Instructional guidelines and brief teacher training sessions may facilitate expansion across institutions. These strategies enable consistent implementation without altering the program’s core methodology.