Hermetia illucens L. Frass in Promoting Soil Fertility in Farming Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Greenhouse Experiment

2.2. Data Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

- In the podzol, fresh weight production was consistently, and significantly, higher in the mixed and exclusively organic treatments, despite the fact that the dry weight production in the same treatments did not differ significantly from that of the exclusively chemical treatment.

- In the calcisol, there were no significant differences between treatments, both for fresh and dry weight.

- In the fluvisol, as for the calcisol, there were no significant differences for fresh weight production. However, dry mass production was consistently higher in the mixed and exclusively organic treatments, although only the MOT(75:25) treatment was significantly higher than the exclusively chemical treatment, in contrast to what was registered in the first year of the trial.

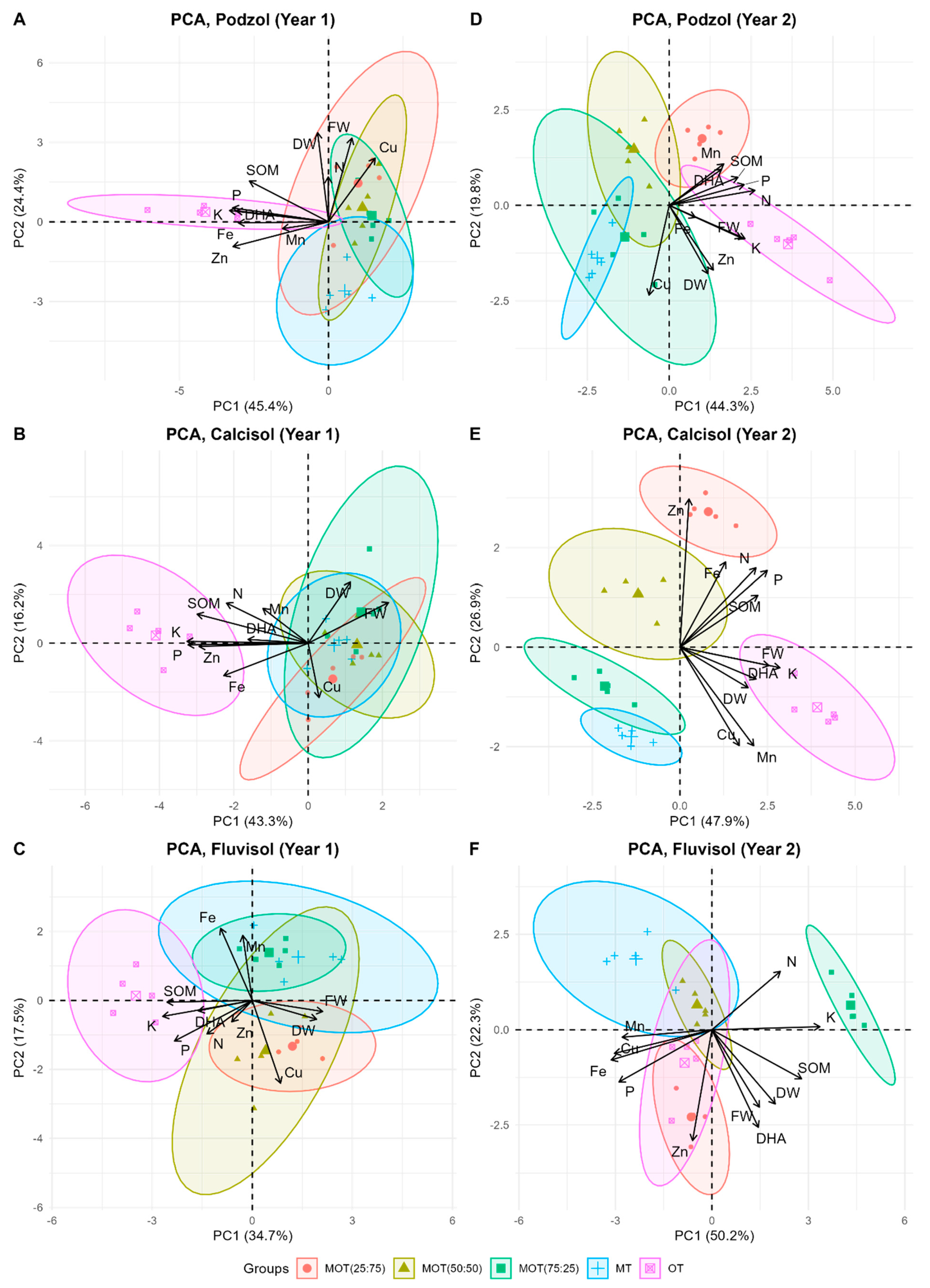

4. Principal Component Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects—Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security; FAO Forestry Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2013; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, N.J.; Weldon, C.W. Nutritional content and bioconversion efficiency of Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): Harvest as larvae or prepupae? Austral Entomol. 2021, 60, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsina, J. Can organic sources of nutrients increase crop yields to meet global food demand? Agronomy 2018, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, I.; Lopes, I.G.; Murta, D.; Lidon, F.; Fareleira, P.; Esteves, C.; Moreira, O.; Menino, R. Agronomic potential of Hermetia illucens frass in the cultivation of ryegrass in distinct soils. J. Insects Food Feed 2024, 11, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonaco, G.; Franco, A.; De Smet, J.; Scieuzo, C.; Salvia, R.; Falabella, P. Larval Frass of Hermetia illucens as Organic Fertilizer: Composition and Beneficial Effects on Different Crops. Insects 2024, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 11465:1993; Soil Quality—Determination of Dry Matter and Water Content on a Mass Basis—Gravimetric Method. International Organization Standardization: Genève, Switzerland, 1993.

- Casida, L.E.; Klein, D.A.; Santoro, T. Soil Dehydrogenase Activity. Soil Sci. 1964, 98, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menino, R.; Felizes, F.; Castelo-Branco, M.A.; Fareleira, P.; Moreira, O.; Nunes, R.; Murta, D. Agricultural value of Black Soldier Fly larvae frass as organic fertilizer on ryegrass. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setti, L.; Francia, E.; Pulvirenti, A.; Gigliano, S.; Zaccardelli, M.; Pane, C.; Caradonia, F.; Bortolini, S.; Maistrello, L.; Ronga, D. Use of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens (L.), Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larvae processing residue in peat-based growing media. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, I.G.; Braos, L.B.; Cruz, M.C.P.; Vidotti, R.M. Valorization of animal waste from Aquaculture through composting: Nutrient recovery and nitrogen mineralization. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Schneckenberger, K. Review of estimation of plant rhizodeposition and their contribution to soil organic matter formation. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2004, 50, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.; Wallenstein, M.; Bradford, M. Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.G.; DeForest, J.L.; Marxsen, J.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Stromberger, M.E.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Weintraub, M.N.; Zoppini, A. Soil enzymes in a changing environment: Current knowledge and future directions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 58, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Ping, Y.Y.; Cai, H.Y.; Tan, Q.; Liu, C.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.W. Effects of Soil Properties on Pb, Cd, and Cu Contents in Tobacco Leaves of Longyan, China, and Their Prediction Models. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 9216995, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolinska, A.; Stepniewsk, Z. Dehydrogenase activity in the soil environment. In Dehydrogenases; Canuto, R.A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, S.; Sanchez, L.; Alvarez, J.; Valverde, A.; Galindo, P.; Igual, J.; Peix, A.; Santa-Regina, I. Correlation Among Soil Enzyme Activities Under Different Forest System Management Practices. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E.; Lasota, J.; Gruba, P. Effect of Temperate Forest Tree Species on Soil Dehydrogenase and Urease Activities in Relation to Other Properties of Soil Derived from Loess and Glaciofluvial Sand. Ecol. Res. 2016, 31, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, S.M.; Villamil, M.B. Meta-analysis approach to assess effect of tillage on microbial biomass and enzyme activities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 97, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D.; Scow, K.M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms—A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünemann, E.K.; Bongiorno, G.; Bai, Z.; Creamer, R.E.; De Deyn, G.; de Goede, R.; Fleskens, L.; Geissen, V.; Kuyper, T.W.; Mäder, P.; et al. Soil quality—A critical review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Thornton, P.E.; Post, W.M. A global analysis of soil microbial biomass carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenbach, C.; Frey, S.; Grandy, A. Direct evidence for microbial-derived soil organic matter formation and its ecophysiological controls. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drinkwater, L.E.; Snapp, S.S. Nutrients in agroecosystems: Re-thinking the management paradigm. Adv. Agron. 2007, 92, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | 1st Year (g pot−1) | 2nd Year (g pot−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW | DW | FW | DW | |

| Gleyic Podzol | ||||

| MT | 34 ± 8.3 b | 5 ± 1.44 b | 14 ± 2.44 b | 3.3 ± 0.64 ab |

| MOT(75:25) | 61 ± 5.7 a | 11 ± 2.10 a | 16 ± 1.72 b | 3.4 ± 0.74 ab |

| MOT(50:50) | 64 ± 10.6 a | 13 ± 1.88 a | 16 ± 1.49 b | 2.8 ± 0.34 b |

| MOT(25:75) | 65 ± 21.8 a | 13 ± 3.57 a | 15 ± 1.29 b | 2.9 ± 0.28 b |

| OT | 53 ± 3.3 ab | 12 ± 1.09 a | 23 ± 3.47 a | 3.9 ± 0.53 a |

| Haplic Calcisol | ||||

| MT | 89 ± 11.6 ab | 17 ± 1.42 ns | 21 ± 1.57 b | 4.1 ± 0.67 ns |

| MOT(75:25) | 109 ± 5.2 a | 20 ± 4.90 ns | 23 ± 2.78 b | 4.4 ± 0.75 ns |

| MOT(50:50) | 103 ± 5.6 a | 18 ± 1.37 ns | 23 ± 4.61 b | 4.2 ± 0.96 ns |

| MOT(25:75) | 90 ± 21.4 ab | 17 ± 1.79 ns | 25 ± 2.98 b | 4.3 ± 0.61 ns |

| OT | 80 ± 7.8 b | 16 ± 2.60 ns | 32 ± 2.30 a | 5.5 ± 1.02 ns |

| Haplic Fluvisol | ||||

| MT | 112 ± 22.7 a | 22 ± 5.26 ns | 19 ± 2.62 c | 3.3 ± 0.64 b |

| MOT(75:25) | 115 ± 13.3 a | 20 ± 2.39 ns | 25 ± 3.42 ab | 4.6 ± 0.62 a |

| MOT(50:50) | 112 ± 10.9 a | 21 ± 3.97 ns | 20 ± 2.65 bc | 3.6 ± 0.48 ab |

| MOT(25:75) | 111 ± 9.5 a | 20 ± 2.00 ns | 23 ± 2.22 abc | 4.2 ± 0.41 ab |

| OT | 91 ± 3.6 b | 16 ± 1.90 ns | 27 ± 3.84 a | 4.2 ± 0.61 ab |

| Treatment | SOM (%) | N (%) | P (mg kg−1) | K2O (mg kg−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Year | 2nd Year | 1st Year | 2nd Year | 1st Year | 2nd Year | 1st Year | 2nd Year | |

| Gleyic Podzol | ||||||||

| MT | 0.36 ± 0.05 c | nd b | 0.03 ± 0.01 nsA | 0.02 ± 0.003 dB | 9.2 ± 1.05 bc | 9.0 | 13 ± 2.11 b | 16 ± 1.31 b |

| MOT(75:25) | 0.39 ± 0.09 bcB | 0.57 ± 0.03 aA | 0.04 ± 0.02 ns | 0.03 ± 0.005 c | 8.0 ± 1.22 c | nd | 14 ± 0.52 bB | 16 ± 1.07 bA |

| MOT(50:50) | 0.46 ± 0.01 bcB | 0.56 ± 0.04 aA | 0.03 ± 0.01 ns | 0.03 ± 0.001 c | 8.7 ± 0.83 c | 12.7 | 16 ± 1.69 b | 17 ± 0.00 b |

| MOT(25:75) | 0.47 ± 0.05 aB | 0.61 ± 0.02 aA | 0.04 ± 0.01 ns | 0.04 ± 0.005 b | 12.5 ± 3.13 b | 18.7 | 15 ± 3.58 b | 17 ± 0.00 b |

| OT | 0.59 ± 0.04 aB | 0.73 ± 0.03 aA | 0.04 ± 0.01 nsB | 0.05 ± 0.005 aA | 19.9 ± 2.25 a | 25.9 | 99 ± 13.1 aA | 36 ± 2.94 aB |

| Haplic Calcisol | ||||||||

| MT | 1.28 ± 0.05 b | 1.39 ± 0.09 b | 0.11 ± 0.02 b | 0.11 ± 0.003 c | 6.7 ± 0.47 c | nd | 88 ± 8.44 bA | 48 ± 1.07 cB |

| MOT(75:25) | 1.32 ± 0.15 b | 1.39 ± 0.14 b | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.11 ± 0.006 bc | 7.3 ± 1.22 c | nd | 75 ± 3.16 bA | 42 ± 1.31 dB |

| MOT(50:50) | 1.27 ± 0.02 bB | 1.56 ± 0.15 abA | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 0.12 ± 0.001 b | 8.1 ± 0.87 bc | 9.6 | 75 ± 4.77 bA | 46 ± 1.70 cB |

| MOT(25:75) | 1.25 ± 0.08 bB | 1.64 ± 0.07 aA | 0.10 ± 0.01 bB | 0.15 ± 0.013 aA | 10.7 ± 1.96 b | 14.8 | 83 ± 6.29 bA | 50 ± 2.94 bB |

| OT | 1.78 ± 0.11 a | 1.72 ± 0.10 a | 0.14 ± 0.02 a | 0.15 ± 0.014 a | 21.9 ± 2.41 a | 16.6 | 129 ± 18.9 aA | 63 ± 1.07 aB |

| Haplic Fluvisol | ||||||||

| MT | 2.01 ± 0.03 cB | 2.18 ± 0.10 cA | 0.15 ± 0.02 ns | 0.14 ± 0.002 b | 49.8 ± 1.55 b | 40.2 | 203 ± 15.0 cA | 152 ± 2.01 dB |

| MOT(75:25) | 2.19 ± 0.05 bB | 2.76 ± 0.11 aA | 0.14 ± 0.01 nsB | 0.18 ± 0.005 aA | 51.7 ± 3.99 b | 23.9 | 238 ± 9.40. bcA | 290 ± 13.1 aA |

| MOT(50:50) | 2.22 ± 0.16 bcB | 2.42 ± 0.08 bA | 0.15 ± 0.04 ns | 0.17 ± 0.003 a | 59.8 ± 4.92 b | 45.9 | 238 ± 12.9 bcA | 171 ± 3.13 cB |

| MOT(25:75) | 1.95 ± 0.09 cB | 2.48 ± 0.13 bA | 0.15 ± 0.02 nsA | 0.13 ± 0.007 bB | 56.3 ± 9.10 b | 46.8 | 253 ± 27.8 bA | 184 ± 4.62 bB |

| OT | 2.57 ± 0.14 a | 2.54 ± 0.15 b | 0.17 ± 0.01 ns | 0.17 ± 0.026 a | 70.1 ± 4.71 a | 44.5 | 352 ± 30.2 aA | 178 ± 2.94 bcB |

| Treatment | Cu (mg kg−1) | Fe (mg kg−1) | Zn (mg kg−1) | Mn (mg kg−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Year | 2nd Year | 1st Year | 2nd Year | 1st Year | 2nd Year | 1st Year | 2nd Year | |

| Gleyic Podzol | ||||||||

| MT | 2.2 ± 0.30 cB | 4.6 ± 0.38 aA | 42 ± 3.86 bB | 96 ± 8.23 aA | 10.6 ± 1.75 b | 9.7 ± 0.42 b | 18 ± 1.56 ns | 17 ± 0.30 d |

| MOT(75:25) | 2.8 ± 0.18 abcB | 4.7 ± 0.25 aA | 38 ± 3.21 bB | 63 ± 1.39 cA | 7.4 ± 0.29 cB | 9.6 ± 0.33 bA | 18 ± 0.87 ns | 21 ± 1.03 b |

| MOT(50:50) | 2.9 ± 0.59 abB | 3.9 ± 0.22 bcA | 42 ± 2.52 bB | 81 ± 4.41 bA | 7.3 ± 0.32 cB | 8.6 ± 0.13 cA | 20 ± 5.43 ns | 19 ± 0.52 c |

| MOT(25:75) | 3.4 ± 0.37 a | 3.8 ± 0.22 c | 38 ± 2.95 bB | 87 ± 1.90 abA | 7.3 ± 1.05 cB | 9.6 ± 0.05 bA | 15 ± 0.55 ns | 24 ± 0.89 a |

| OT | 2.3 ± 0.24 bcB | 4.3 ± 0.16 abA | 54 ± 12.0 aB | 92 ± 8.90 aA | 14.0 ± 1.95 aA | 10.1 ± 0.28 aB | 21 ± 7.98 ns | 21 ± 1.15 b |

| Haplic Calcisol | ||||||||

| MT | 2.9 ± 0.13 B | 5.6 ± 0.14 aA | 68 ± 5.85 abc | 102 ± 7.06 b | 2.7 ± 0.32 b | 3.7 ± 0.10 d | 89 ± 6.54 a | 87 ± 2.37 b |

| MOT(75:25) | 2.9 ± 0.67 B | 4.5 ± 0.30 bA | 63 ± 5.79 cB | 90 ± 3.79 cA | 2.7 ± 0.69 bB | 4.7 ± 0.03 cA | 89 ± 12.8 a | 81 ± 3.54 c |

| MOT(50:50) | 3.0 ± 0.66 B | 4.0 ± 0.20 cA | 66 ± 5.97 bcB | 94 ± 4.91 bcA | 2.5 ± 0.54 bB | 6.3 ± 0.05 bA | 65 ± 5.09 b | 70 ± 1.94 d |

| MOT(25:75) | 3.3 ± 0.28 B | 4.6 ± 0.15 bA | 73 ± 6.88 abB | 127 ± 9.84 aA | 2.8 ± 0.65 bB | 7.9 ± 0.11 aA | 59 ± 4.06 b | 75 ± 1.92 d |

| OT | 2.9 ± 0.14 B | 5.9 ± 0.22 aA | 77 ± 3.40 aB | 105 ± 3.01 bA | 4.2 ± 0.08 a | 4.6 ± 0.10 c | 88 ± 2.17 a | 105 ± 2.50 a |

| Haplic Fluvisol | ||||||||

| MT | 3.6 ± 0.21 bB | 7.1 ± 0.18 abA | 303 ± 13.9 aB | 381 ± 47.5 abA | 3.4 ± 0.28 | 3.7 ± 0.14 e | 314 ± 8.69 b | 324 ± 16.2 ab |

| MOT(75:25) | 4.0 ± 0.23 bB | 5.9 ± 0.17 dA | 275 ± 18.8 abc | 261 ± 5.73 c | 3.1 ± 0.76 B | 4.2 ± 0.08 dA | 379 ± 23.4 aA | 253 ± 6.00 cB |

| MOT(50:50) | 6.9 ± 0.44 a | 6.5 ± 0.25 c | 262 ± 20.7 bcB | 343 ± 10.6 bA | 3.2 ± 0.92 B | 6.1 ± 0.03 bA | 298 ± 9.72 b | 308 ± 6.35 b |

| MOT(25:75) | 6.3 ± 0.35 a | 6.8 ± 0.15 bc | 252 ± 8.42 cB | 394 ± 25.8 a | 3.8 ± 1.14 B | 9.3 ± 0.29 aA | 297 ± 21.8 b | 298 ± 10.5 b |

| OT | 3.9 ± 0.60 bB | 7.2 ± 0.24 aA | 300 ± 25.3 abB | 414 ± 9.79 aA | 3.8 ± 0.96 | 5.6 ± 0.28 c | 322 ± 35.2 b | 349 ± 34.0 a |

| Treatment | DHA (µg TPF/g Dry Soil Hour) In the End of the 1st Year | DHA (µg TPF/g Dry Soil Hour) In the End of the 2nd Year |

|---|---|---|

| Gleyic Podzol | ||

| MT | 0.314 ± 0.05 b | 0.478 ± 0.17 ns |

| MOT(75:25) | 0.348 ± 0.05 bB | 0.503 ± 0.11 nsA |

| MOT(50:50) | 0.117 ± 0.06 bB | 0.623 ± 0.13 nsA |

| MOT(25:75) | 0.416 ± 0.17 bB | 0.756 ± 0.24 nsA |

| OT | 1.073 ± 0.17 a | 0.743 ± 0.19 ns |

| Haplic Calcisol | ||

| MT | 4.593 ± 0.45 ns | 5.619 ± 1.01 b |

| MOT(75:25) | 4.834 ± 1.88 ns | 4.941 ± 0.52 b |

| MOT(50:50) | 6.040 ± 0.10 ns | 6.095 ± 0.83 b |

| MOT(25:75) | 5.775 ± 0.75 ns | 5.440 ± 0.99 b |

| OT | 6.351 ± 1.06 nsB | 8.108 ± 0.84 aA |

| Haplic Fluvisol | ||

| MT | 5.146 ± 0.55 nsA | 3.471 ± 0.31 dB |

| MOT(75:25) | 6.754 ± 0.84 nsA | 5.292 ± 0.59 abB |

| MOT(50:50) | 7.357 ± 1.20 nsA | 4.432 ± 0.46 cB |

| MOT(25:75) | 4.902 ± 0.44 nsB | 5.947 ± 0.37 aA |

| OT | 7.076 ± 1.43 nsA | 4.904 ± 0.41 bcB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menino, R.; Esteves, C.; Fareleira, P.; Mano, R.; Antunes, J.; Rehan, I.; Murta, D.; Moreira, O. Hermetia illucens L. Frass in Promoting Soil Fertility in Farming Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411058

Menino R, Esteves C, Fareleira P, Mano R, Antunes J, Rehan I, Murta D, Moreira O. Hermetia illucens L. Frass in Promoting Soil Fertility in Farming Systems. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411058

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenino, Regina, Catarina Esteves, Paula Fareleira, Raquel Mano, Joana Antunes, Iryna Rehan, Daniel Murta, and Olga Moreira. 2025. "Hermetia illucens L. Frass in Promoting Soil Fertility in Farming Systems" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411058

APA StyleMenino, R., Esteves, C., Fareleira, P., Mano, R., Antunes, J., Rehan, I., Murta, D., & Moreira, O. (2025). Hermetia illucens L. Frass in Promoting Soil Fertility in Farming Systems. Sustainability, 17(24), 11058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411058