Beyond the Ivory Tower: How Dutch Universities Convert Missions into ESG Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. ESG in Higher Education

2.2. University Missions: Education, Research, and Entrepreneurship

2.3. Education and ESG Performance

2.4. Research and ESG Performance

2.5. Entrepreneurship and ESG Performance

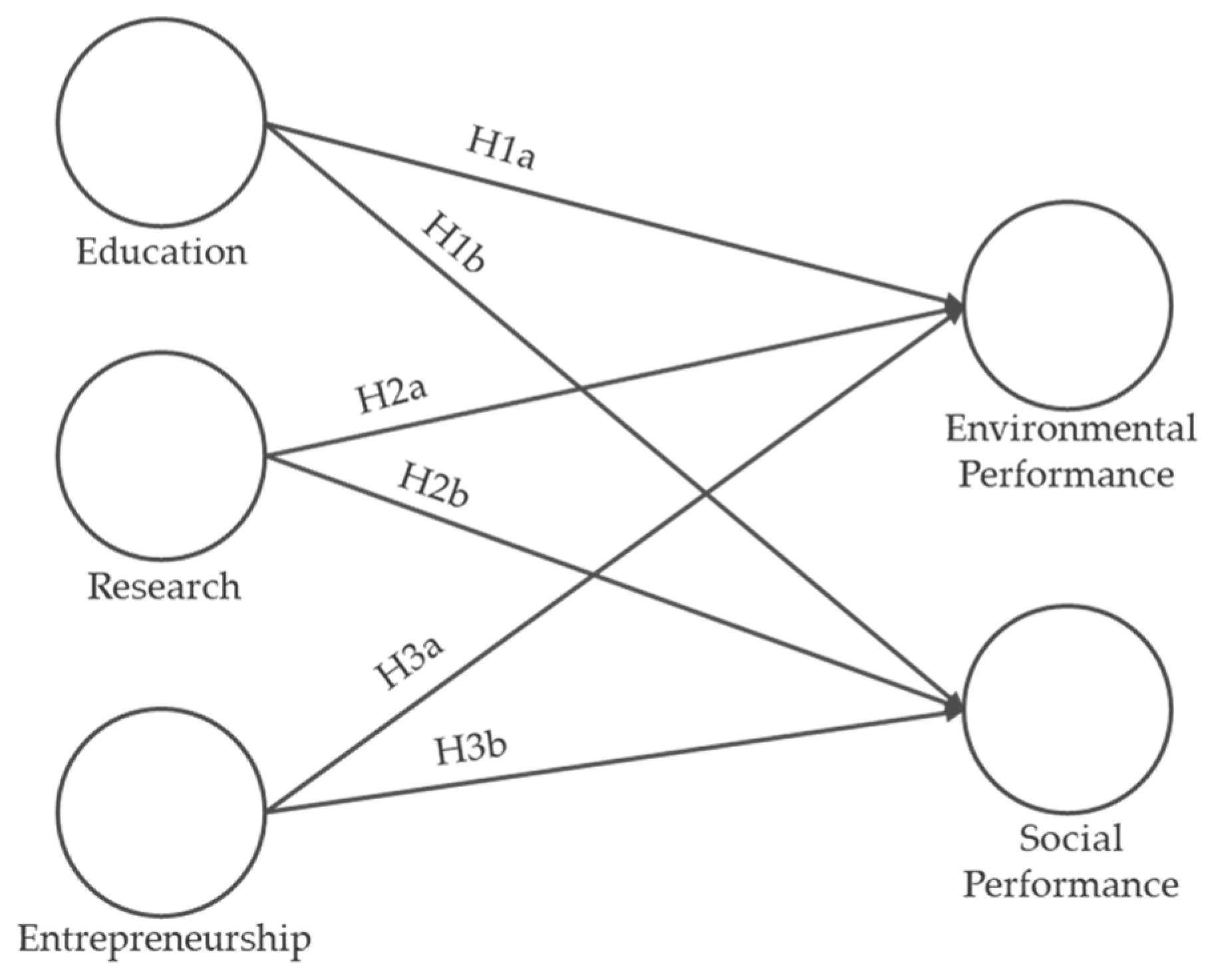

2.6. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Variables

3.2. Analytical Approach: PLS-SEM

4. Results

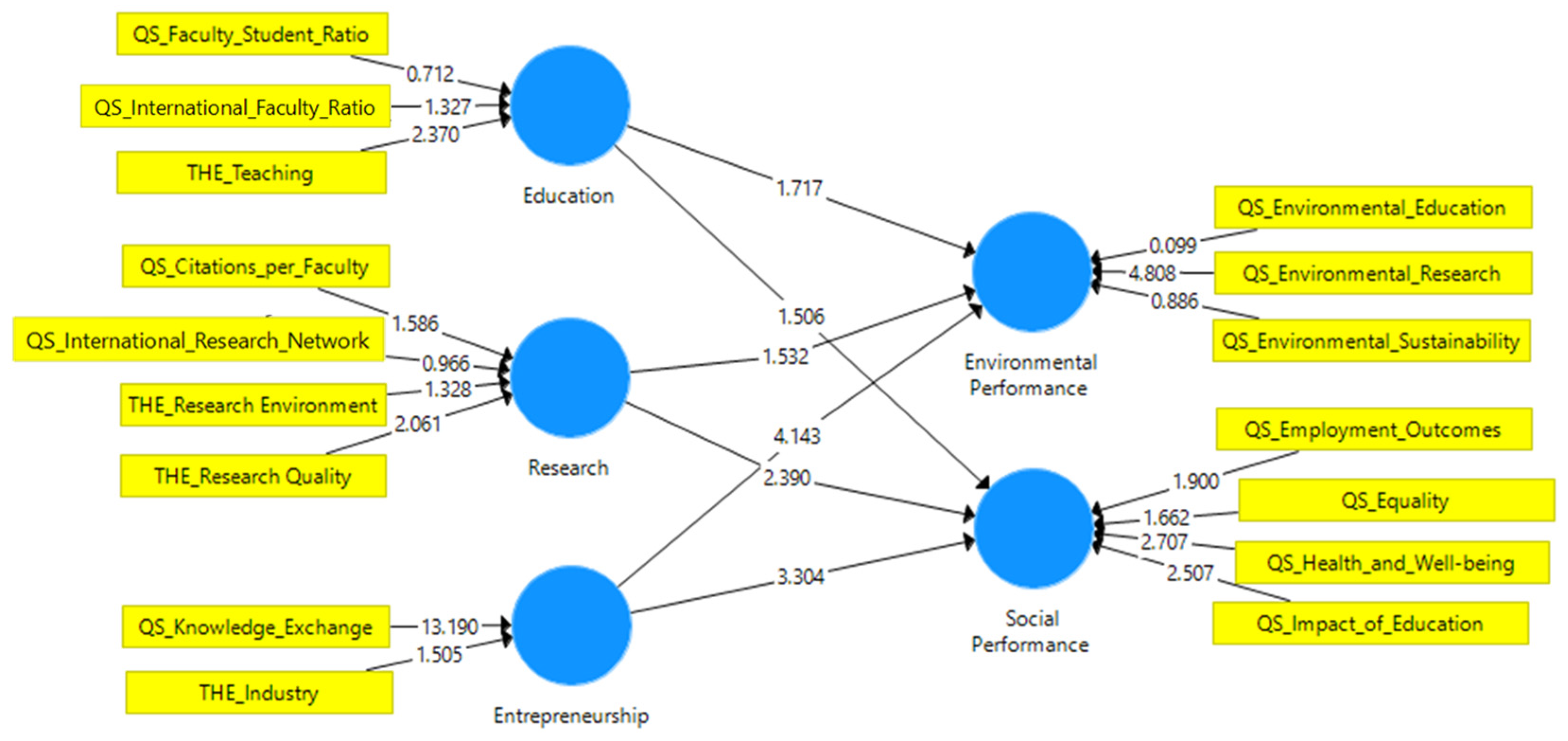

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical and Policy Implications

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| PLS-SEM | Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| THE | Times Higher Education |

| WUR | World University Rankings |

References

- Schimperna, F.; Schimperna, M.; Gigli, S.; Manzari, A. Sustainability and higher education: Exploring ESG drivers of university performance through a multi-stakeholder lens. Int. J. Inf. Oper. Manag. Educ. 2025, 8, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QS. Sustainability is Powering the Future of Rankings. 2024. Available online: https://qs-gen.com/sustainability-is-powering-the-future-of-rankings/#:~:text=The%20QS%20Sustainability%20Ranking%20is,for%20in%202025%20and%20beyond (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ghorbani, A.; Blankesteijn, M.L. Governance arrangements for academic entrepreneurship: Structures, processes, and mechanisms. Manag. Rev. Q. 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarejos, F.; Frota, M.N.; Gustavson, L.M. Higher education institutions: A strategy towards sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouwen, K. Strategy, Structure and Culture of the Hybrid University: Towards the University of the 21st Century. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2000, 6, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Fayolle, A.; Di Guardo, M.C.; Lamine, W.; Mian, S. Re-viewing the entrepreneurial university: Strategic challenges and theory building opportunities. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 63, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villiers, C.D.; Dimes, R.; Houqe, M.N.; Hu, N.; Molinari, M. University sustainability performance as a catalyst for societal change. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2025, 38, 1428–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorani, G.; Di Gerio, C. Reporting University Performance through the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda: Lessons Learned from Italian Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M.F.; Ciaburri, M.; Tiscini, R. The challenge of sustainable development goal reporting: The first evidence from italian listed companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, É.C.B.; Poltronieri, C.F.; Xavier, Y.S.M.; de Oliveira, O.J. What ESG Has Not (Yet) Delivered: Proposition of a Framework to Overcome Its Hurdles. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankesteijn, M.; Bossink, B.; Sijde, P.V.D. Science-based entrepreneurship education as a means for university-industry technology transfer. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 779–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aceves, L.; Couto-Ortega, M.; Minola, T.; Markuerkiaga, L.; Hahn, D. Entrepreneurial University governance: The case of a Cooperative University. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 2200–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P.G.; Salmi, J. The Road to Academic Excellence: The Making of World-Class Research Universities; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, L.M.; Hollister, R.M. Moving Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Expanding Global Movement of Engaged Universities. In Higher Education in the World 5; Hall, B.L., Tandon, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2014; pp. 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Moyaa, M.; Álvaro-Moyaa, A.; Puigb, N. Supply-driven academic innovation. Establishing entrepreneurship education as a discipline in Spain (1974–2000s). Manag. Organ. Hist. 2025, 20, 160–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouragini, I.; Labidi, M.; Louzir, A.B.H. The Role of Entrepreneurial Universities in Promoting Entrepreneurship Education: A Comparative Study Between Public and Private Technology Institutes. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 10985–11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Khalil, A.G. Integrating sustainability into higher education challenges and opportunities for universities worldwide. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, R.; Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y.; Mckeown, R.; Hopkins, C. Contributions of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to Quality Education: A Synthesis of Research. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholon, R.; Sigahi, T.F.; Cazeri, G.T.; Siltori, P.F.D.S.; Lourenzani, W.L.; Satolo, E.G.; Caldana, A.C.F.; Moraes, G.H.S.M.D.; Martins, V.W.B.; Rampasso, I.S. Training Future Managers to Address the Challenges of Sustainable Development: An Innovative, Interdisciplinary, and Multiregional Experience on Corporate Sustainability Education. World 2024, 5, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.V.; Wagner, C.M.; Nutt, C.T.; Binagwaho, A. The future of global health education: Training for equity in global health. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, P. New directions in renewable energy education. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QS. QS World University Rankings: Methodology. 2025. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/world-university-rankings/methodology (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- THE Higher Education. World University Rankings 2024: Methodology. 2025. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/world-university-rankings-2024-methodology (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Buerkle, A.; O’Dell, A.; Matharu, H.; Buerkle, L.; Ferreira, P. Recommendations to align higher education teaching with the UN sustainability goals—A scoping survey. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2023, 5, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P.; Duggal, H.K.; Lim, W.M.; Thomas, A.; Shiva, A. Student well-being in higher education: Scale development and validation with implications for management education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furco, A. The Engaged Campus: Toward a Comprehensive Approach to Public Engagement. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2010, 58, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drissi, M.; Meftah, S.; Skalli, L. The role of universities in implementing the sustainable development goals (SDGs) a case study of Hassan first university 2018–2023. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, S. The Role of Universities in Regional Innovation Ecosystems; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://www.eua.eu/images/pdf/eua_innovation_ecosystem_report.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ruano-Borbalan, J.-C. New missions for universities in the era of innovation: European and global perspectives for excellence and sustainability. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2024, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozirog, K.; Lucaci, S.-M.; Berghmans, S. Universities as Key Drivers of Sustainable Innovation Ecosystems; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://www.eua.eu/downloads/publications/innovation%20report.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Stuckrath, C.; Chappin, M.M.H.; Worrell, E. What Drives Successful Campus Living Labs? The Case of Utrecht University. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, D.; Salgado, J.F.; Moscoso, S. Prevalence and Correlates of Academic Dishonesty: Towards a Sustainable University. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, H.; Scholten, V.E.; Wubben, E.F.M.; Omta, S.W.F.O. The Role of Academic Spin-Offs Facilitators in Navigation of the Early Growth Stage Critical Junctures. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevnaker, B.H.; Misganaw, B.A. Technology transfer offices and the formation of academic spin-off entrepreneurial teams. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2022, 34, 977–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías-Prada, J.F.; Silva, Y.; Zapata, Á.M. The role of universities in Latin American social entrepreneurship ecosystems: A gender perspective. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2024, 16, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gomez, F.-I.; Miranda, F.J.; Mera, A.C.; Mayo, J.P. The Spin-Off as an Instrument of Sustainable Development: Incentives for Creating an Academic USO. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieg, P.; Posadzińska, I.; Jóźwiak, M. Academic entrepreneurship as a source of innovation for sustainable development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Lin, H.; Clarke, A. Cross-Sector Social Partnerships for Social Change: The Roles of Non-Governmental Organizations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, T.; Martínez-Martínez, S.L.; Ventura, R.; Galán-Muros, V. The creation of academic spin-offs: University-Business Collaboration matters. J. Technol. Transf. 2025, 50, 1567–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Unur, M.; Karakas, H.; Derdowski, L.A.; Linge, T.T.; Arasli, H. Measuring inferred responsible leadership intentions: Formative index development. Qual. Quant. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Definition (Role in Study) | Indicators (Source) |

|---|---|---|

| Education Mission | The university’s strength in teaching and learning (first mission). A well-resourced, high-quality educational environment that develops student knowledge and skills. |

|

| Research Mission | University’s research output and quality (second mission). The capacity to generate influential knowledge and innovations. |

|

| Entrepreneurship Mission | University’s engagement and knowledge transfer activities beyond academia (third mission). Involvement with industry and community to apply knowledge. |

|

| Environmental Performance | University’s performance on the environmental sustainability dimensions of ESG. Reflects sustainable operations, research, and teaching related to the environment. |

|

| Social Performance | University’s performance on social responsibility and impact dimensions of ESG. Reflects contributions to society, equity, and well-being. |

|

| Indicators | VIF |

|---|---|

| Citations per Faculty | 1.213 |

| Employment Outcomes | 1.071 |

| Environmental Education | 2.215 |

| Environmental Research | 1.551 |

| Environmental Sustainability | 1.677 |

| Equality | 1.597 |

| Faculty Student Ratio | 1.813 |

| Health and Well-being | 1.672 |

| Impact of Education | 1.969 |

| International Faculty Ratio | 1.359 |

| International Research Network | 1.731 |

| Knowledge Exchange | 1.04 |

| Education → Environmental Perf. | 2.357 |

| Education → Social Perf. | 2.357 |

| Research → Environmental Perf. | 2.798 |

| Research → Social Perf. | 2.798 |

| Entrepreneurship → Environ. Perf. | 1.785 |

| Entrepreneurship → Social Perf. | 1.785 |

| Hypothesized Path | β (Path Coefficient) | t-Statistic | p-Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Education → Environmental Perf. | 0.452 | 1.717 | 0.086 | No (marginal) |

| H1b: Education → Social Perf. | −0.356 | 1.506 | 0.132 | No |

| H2a: Research → Environmental Perf. | −0.389 | 1.532 | 0.126 | No |

| H2b: Research → Social Perf. | 0.544 | 2.390 | 0.017 | Yes |

| H3a: Entrepreneurship → Environ. Perf. | 0.789 | 4.143 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H3b: Entrepreneurship → Social Perf. | 0.706 | 3.304 | 0.001 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ghorbani, A.; Blankesteijn, M.L. Beyond the Ivory Tower: How Dutch Universities Convert Missions into ESG Performance. Sustainability 2026, 18, 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020624

Ghorbani A, Blankesteijn ML. Beyond the Ivory Tower: How Dutch Universities Convert Missions into ESG Performance. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):624. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020624

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhorbani, Amir, and Marie Louise Blankesteijn. 2026. "Beyond the Ivory Tower: How Dutch Universities Convert Missions into ESG Performance" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020624

APA StyleGhorbani, A., & Blankesteijn, M. L. (2026). Beyond the Ivory Tower: How Dutch Universities Convert Missions into ESG Performance. Sustainability, 18(2), 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020624