Divergent Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Dynamics Across Land Use Types in Hunan Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

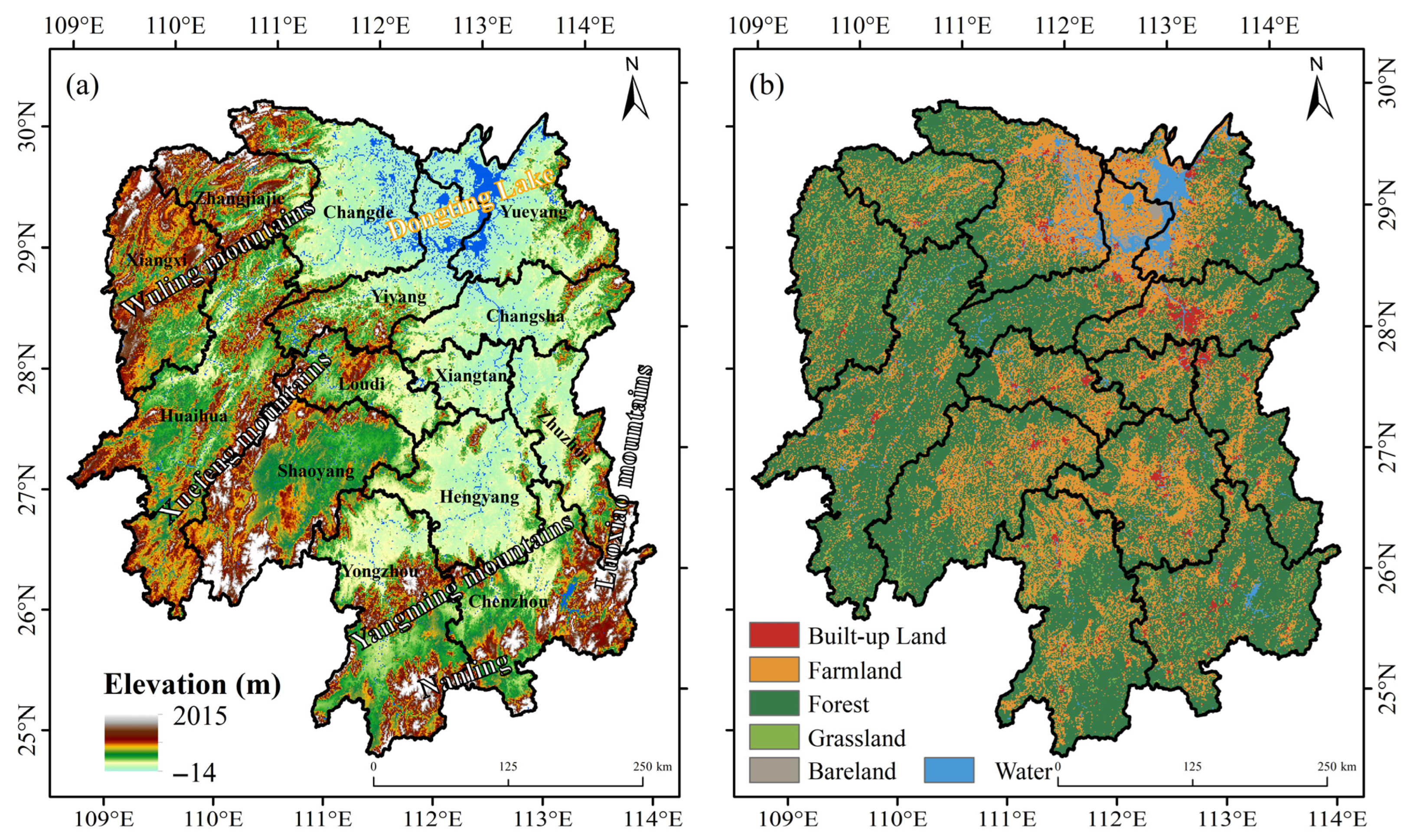

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. kNDVI Calculation

2.3.2. Trend Analysis and Significance Test

2.3.3. Partial Correlation Analysis

2.3.4. Relative Contribution Decomposition Method

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Vegetation kNDVI

3.2. Characteristics of Climate Factor Variations and Their Impacts on Vegetation Dynamics

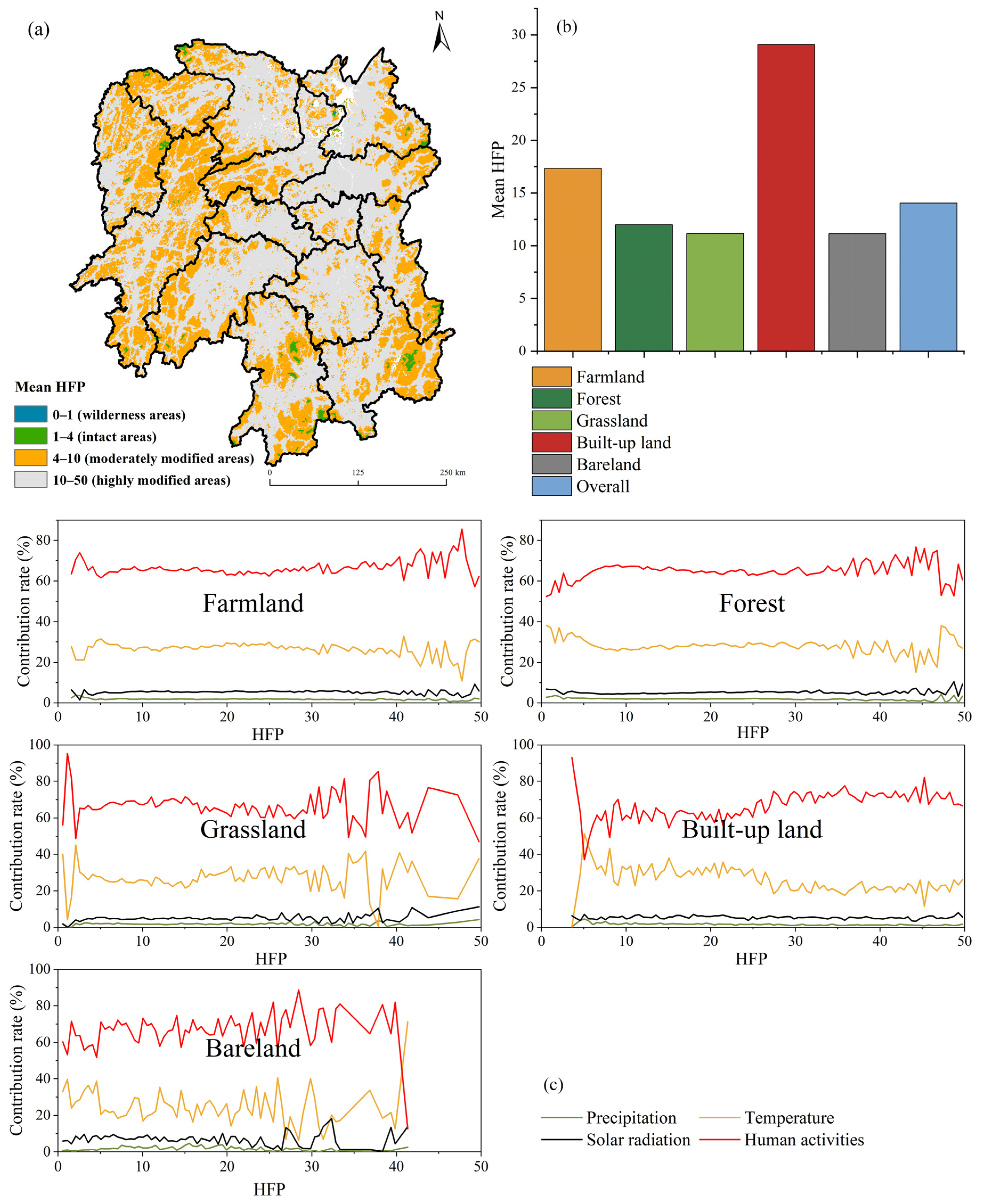

3.3. Quantification of Contribution Rate

3.4. Effects of Human Activities on Vegetation Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Vegetation Greening Trends and Ecological Restoration

4.2. Impact of Driving Factors on Vegetation Dynamics

4.3. Differentiated Responses Across Land Use Types

4.4. Policy Implication and Adaptive Management Strategies

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; Blanco, G. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gerten, D.; Schaphoff, S.; Haberlandt, U.; Lucht, W.; Sitch, S. Terrestrial Vegetation and Water Balance—Hydrological Evaluation of a Dynamic Global Vegetation Model. J. Hydrol. 2004, 286, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Yin, G.; Tan, J.; Cheng, L.; Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Mao, J.; Myneni, R.B.; Peng, S. Detection and Attribution of Vegetation Greening Trend in China over the Last 30 Years. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozyavuz, M.; Bilgili, B.; Salıcı, A. Determination of Vegetation Changes with NDVI Method. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2015, 16, 264–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Lin, K.; Zeng, Z.; Lan, X.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L. Earth Greening and Climate Change Reshaping the Patterns of Terrestrial Water Sinks and Sources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2410881122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.H.; et al. A Global Overview of Drought and Heat-Induced Tree Mortality Reveals Emerging Climate Change Risks for Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Ding, Y.; Peng, S. Temporal effects of climate on vegetation trigger the response biases of vegetation to human activities. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 31, e01822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanniah, K.D.; Beringer, J.; North, P.; Hutley, L. Control of Atmospheric Particles on Diffuse Radiation and Terrestrial Plant Productivity: A Review. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2012, 36, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Park, T.; Wang, X.; Piao, S.; Xu, B.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Fuchs, R.; Brovkin, V.; Ciais, P.; Fensholt, R. China and India Lead in Greening of the World through Land-Use Management. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Güneralp, B.; Hutyra, L.R. Global Forecasts of Urban Expansion to 2030 and Direct Impacts on Biodiversity and Carbon Pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16083–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhao, K.; Huang, M.; Li, Y. One− off Irrigation Enhances Wheat Yield and Water Productivity: Evidence from Meta− Analysis and a Three− Year and Three− Site Field Experiment. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 317, 109628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Liu, X. Combined Application of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizers Increases Soil Organic Carbon Storage in Cropland Soils. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, R.; Zhao, T.; Liu, Z.; Tu, X. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of NDVI and Its Influencing Factors in China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemani, R.R.; Keeling, C.D.; Hashimoto, H.; Jolly, W.M.; Piper, S.C.; Tucker, C.J.; Myneni, R.B.; Running, S.W. Climate-Driven Increases in Global Terrestrial Net Primary Production from 1982 to 1999. Science 2003, 300, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Z. Ecological Restoration Programs Dominate Vegetation Greening in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, D. Spatiotemporal Variation of Vegetation Coverage and Its Associated Influence Factor Analysis in the Yangtze River Delta, Eastern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 32866–32879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Piao, S.; Myneni, R.B.; Huang, M.; Zeng, Z.; Canadell, J.G.; Ciais, P.; Sitch, S.; Friedlingstein, P.; Arneth, A. Greening of the Earth and Its Drivers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Tian, J.; Tian, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Using NDVI-NSSI Feature Space for Simultaneous Estimation of Fractional Cover of Non-Photosynthetic Vegetation and Photosynthetic Vegetation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Valls, G.; Campos-Taberner, M.; Moreno-Martínez, Á.; Walther, S.; Duveiller, G.; Cescatti, A.; Mahecha, M.D.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; García-Haro, F.J.; Guanter, L. A Unified Vegetation Index for Quantifying the Terrestrial Biosphere. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bao, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, C.; Xie, M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J. The Time Lag Effects and Interaction among Climate, Soil Moisture, and Vegetation from In Situ Monitoring Measurements across China. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Park, T.; Chen, C.; Lian, X.; He, Y.; Bjerke, J.W.; Chen, A.; Ciais, P.; Tømmervik, H.; et al. Characteristics, Drivers and Feedbacks of Global Greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, A.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, M. What Drives the Vegetation Restoration in Yangtze River Basin, China: Climate Change or Anthropogenic Factors? Ecol. Indic. 2018, 90, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Li, C. Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Vegetation Dynamics in Qilian Mountain National Park, Northwest China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 32, e01947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Jin, N.; Ma, X.; Wu, B.; He, Q.; Yue, C.; Yu, Q. Attribution of Climate and Human Activities to Vegetation Change in China Using Machine Learning Techniques. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 294, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuoku, L.; Wu, Z.; Men, B. Impacts of Climate Factors and Human Activities on NDVI Change in China. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, S.; Mupenzi, C.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Li, Z. Quantitative Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Vegetation Changes in the Upper White Nile River. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Deng, L.; Wang, F.; Han, J. Quantifying the Contributions of Human Activities and Climate Change to Vegetation Net Primary Productivity Dynamics in China from 2001 to 2016. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Zhang, L.; Shrestha, S.; Khadka, N.; Maharjan, L. Spatiotemporal Patterns, Sustainability, and Primary Drivers of NDVI-Derived Vegetation Dynamics (2003–2022) in Nepal. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Azeem, T.; Mahmood, R. Estimation and Attribution of Nonlinear Trend of Water Use Efficiency Using a Normalized Partial Derivative Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Cheng, Y. Evolution and Spatiotemporal Response of Ecological Environment Quality to Human Activities and Climate: Case Study of Hunan Province, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W. Different Impacts of Urbanization on Ecosystem Services Supply and Demand across Old, New and Non-Urban Areas in the ChangZhuTan Urban Agglomeration, China. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Wang, S.-L.; Wang, Q.-K. Ecosystem Carbon Stocks in a Forest Chronosequence in Hunan Province, South China. Plant Soil 2016, 409, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; He, X.; Guan, H.; Cai, Y. Trends and Periodicity of Daily Temperature and Precipitation Extremes during 1960–2013 in Hunan Province, Central South China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 132, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Meng, X.; Ma, J.; He, P. Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms and Threshold Responses of Vegetation at Different Regional Scales in Hunan Province. Forests 2025, 16, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Zhou, C.; Cuidong; Song, H. High-Quality Agricultural Development in the Central China: Empirical Analysis Based on the Dongting Lake Area. Geomatica 2024, 76, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, F.; Godinho, S.; Marques, A.T.; Crispim-Mendes, T.; Pita, R.; Silva, J.P. GEE_xtract: High-Quality Remote Sensing Data Preparation and Extraction for Multiple Spatio-Temporal Ecological Scaling. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 80, 102502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S.; et al. Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform for Remote Sensing Big Data Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a High-Resolution Global Dataset of Monthly Climate and Climatic Water Balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Huang, J.; Du, P.; Su, W.; Miao, S.; Geng, M. A Global Record of Annual Terrestrial Human Footprint Dataset from 2000 to 2018. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocic, M.; Trajkovic, S. Analysis of Changes in Meteorological Variables Using Mann-Kendall and Sen’s Slope Estimator Statistical Tests in Serbia. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 100, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Tian, S.; Zheng, Z.; Zhan, Q.; He, Y. Human Activity Influences on Vegetation Cover Changes in Beijing, China, from 2000 to 2015. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, A.; Yu, D.; Yuan, M.; Li, C. Distinguishing the Impacts of Climate Change and Anthropogenic Factors on Vegetation Dynamics in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Tong, X.; Horion, S.; Feng, L.; Fensholt, R.; Shao, Q.; Tian, F. The Success of Ecological Engineering Projects on Vegetation Restoration in China Strongly Depends on Climatic Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, J. Direct and Indirect Loss of Natural Area from Urban Expansion. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, W.D.; Miller, E.; Jones, A.; García-Rangel, S.; Thornton, H.; McOwen, C. Enhancing Climate Change Resilience of Ecological Restoration—A Framework for Action. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 19, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Z. Nonlinear Spatiotemporal Variability of Gross Primary Production in China’s Terrestrial Ecosystems under Water Energy Constraints. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, K.M.; Brown, J.H. Impact of an Extreme Climatic Event on Community Assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3410–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Fu, Q.; Fang, S.; Wu, J.; He, P.; Quan, Z. Effects of Rapid Urbanization on Vegetation Cover in the Metropolises of China over the Last Four Decades. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 107, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Liang, M.; Hu, Z. Positive Asymmetric Responses Indicate Larger Carbon Sink with Increase in Precipitation Variability in Global Terrestrial Ecosystems. Innov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Cai, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Dong, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, G.; Chen, Z.; He, H.; Guo, W.; et al. Severe Summer Heatwave and Drought Strongly Reduced Carbon Uptake in Southern China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Carreiro, M.M.; Cherrier, J.; Grulke, N.E.; Jennings, V.; Pincetl, S.; Pouyat, R.V.; Whitlow, T.H.; Zipperer, W.C. Coupling Biogeochemical Cycles in Urban Environments: Ecosystem Services, Green Solutions, and Misconceptions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, X.; Smith, R.B.; Oleson, K. Strong Contributions of Local Background Climate to Urban Heat Islands. Nature 2014, 511, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, G.; Luo, T.; Dan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Lv, X. Variation of Net Primary Productivity and Its Drivers in China’s Forests during 2000–2018. Forest Ecosystems 2020, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M.; Murchie, E.H.; Lindfors, A.V.; Urban, O.; Aphalo, P.J.; Robson, T.M. Diffuse Solar Radiation and Canopy Photosynthesis in a Changing Environment. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 311, 108684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M. Global Dimming and Brightening: A Review. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D00D16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, L.M.; Bellouin, N.; Sitch, S.; Boucher, O.; Huntingford, C.; Wild, M.; Cox, P.M. Impact of Changes in Diffuse Radiation on the Global Land Carbon Sink. Nature 2009, 458, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Miguez-Macho, G.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Otero-Casal, C. Hydrologic Regulation of Plant Rooting Depth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10572–10577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Feng, X.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Ji, F.; Pan, S. Increasing Global Vegetation Browning Hidden in Overall Vegetation Greening: Insights from Time-Varying Trends. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 214, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, R.J.; Roderick, M.L.; McVicar, T.R.; Farquhar, G.D. Impact of CO2 Fertilization on Maximum Foliage Cover across the Globe’s Warm, Arid Environments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3031–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhao, X.; Liang, S.; Zhou, T.; Huang, K.; Tang, B.; Zhao, W. Time-Lag Effects of Global Vegetation Responses to Climate Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3520–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Slope | |Z| | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| >0.0005 | >1.96 | Significant improvement/increase |

| >0.0005 | ≤1.96 | Slight improvement/increase |

| −0.0005~0.0005 | ≤1.96 | Stability |

| <−0.0005 | ≤1.96 | Slight degradation/decrease |

| <−0.0005 | >1.96 | Significant degradation/decrease |

| Municipality | Mean Contribution Rate (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | CT | CSR | CH | |

| Changde | 3.26 | 21.38 | 13.54 | 61.83 |

| Yueyang | 2.77 | 24.79 | 10.79 | 61.66 |

| Zhangjiajie | 1.21 | 25.19 | 8.46 | 65.14 |

| Yiyang | 3.06 | 18.32 | 10.32 | 68.3 |

| Xiangxi | 4.12 | 24.7 | 5.24 | 65.94 |

| Huaihua | 4.27 | 29.67 | 3.71 | 62.35 |

| Changsha | 2.27 | 20.78 | 8.88 | 68.06 |

| Loudi | 2.85 | 19.94 | 5.6 | 71.61 |

| Xiangtan | 1.47 | 21.34 | 7.15 | 70.05 |

| Zhuzhou | 1.31 | 35.43 | 4.32 | 58.94 |

| Shaoyang | 3.76 | 30.11 | 3.64 | 62.5 |

| Hengyang | 1.41 | 29.61 | 4.2 | 64.77 |

| Chenzhou | 3.25 | 42.66 | 7.34 | 46.75 |

| Yongzhou | 3.91 | 29.78 | 5.89 | 60.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, Q.; Li, C.; Fang, X.; Wu, Z.; Chun, K.P.; Octavianti, T. Divergent Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Dynamics Across Land Use Types in Hunan Province, China. Sustainability 2026, 18, 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020621

Peng Q, Li C, Fang X, Wu Z, Chun KP, Octavianti T. Divergent Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Dynamics Across Land Use Types in Hunan Province, China. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020621

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Qing, Cheng Li, Xiaohong Fang, Zijie Wu, Kwok Pan Chun, and Thanti Octavianti. 2026. "Divergent Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Dynamics Across Land Use Types in Hunan Province, China" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020621

APA StylePeng, Q., Li, C., Fang, X., Wu, Z., Chun, K. P., & Octavianti, T. (2026). Divergent Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Dynamics Across Land Use Types in Hunan Province, China. Sustainability, 18(2), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020621