Crafting Resilient Audits: Does Distributed Digital Technology Influence Auditor Behavior in the Age of Digital Transformation?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

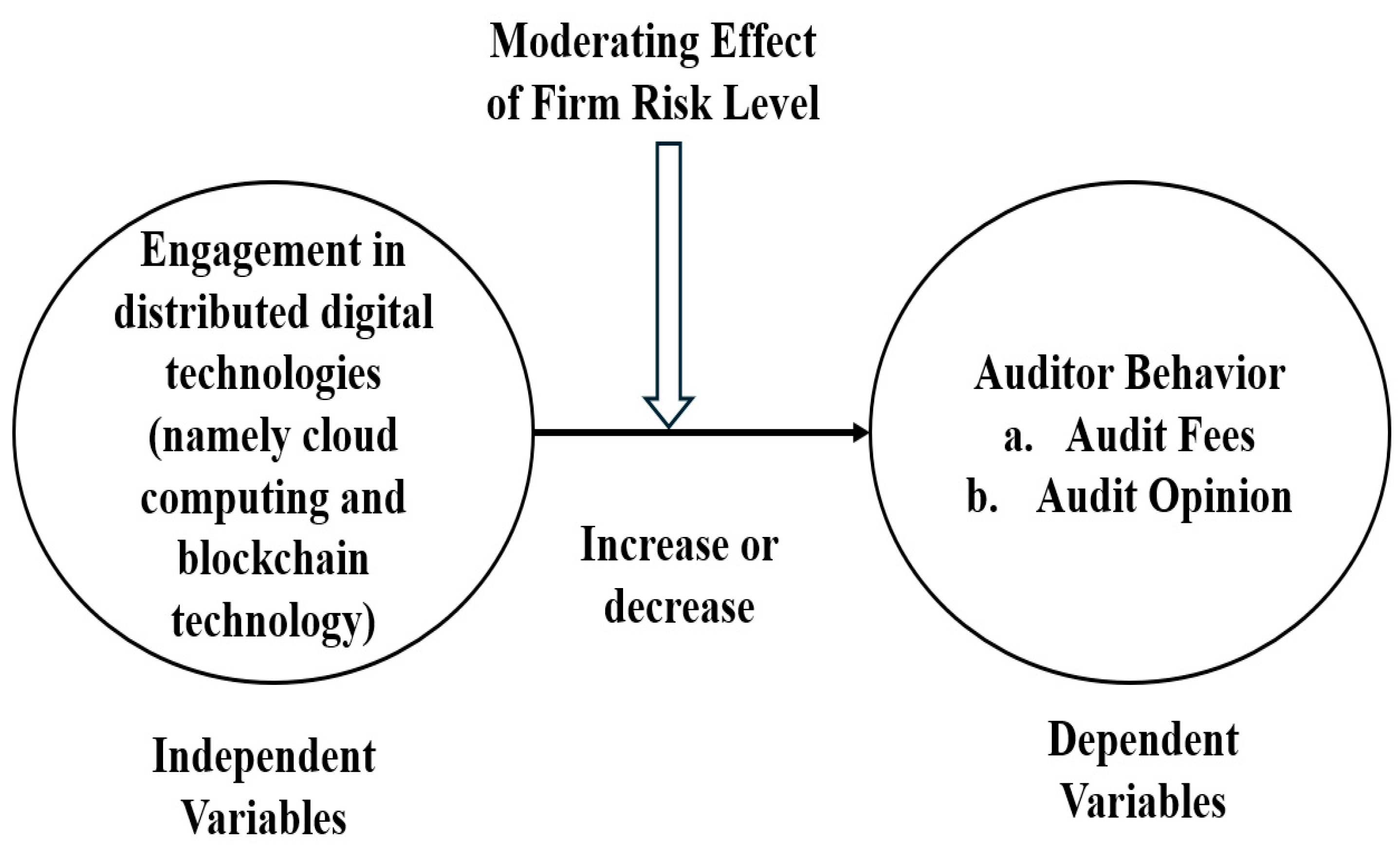

2.1. Enterprise-Level Distributed Digital Technology Application and the Resilient Behavior of Auditors

2.2. Moderating Role of Firm Risk Level

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data

3.2. Empirical Model and Variable Descriptions

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Moderating Variable

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Baseline Results

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Alternate Independent Variable

4.3.2. Lagged Independent Variable

4.3.3. Alternate Estimation Techniques

4.4. Endogeneity Test

Two-Stage Least Squares Method–Instrumental Variable (IV) Approach

4.5. Moderating Role of Firm Risk Level

4.6. Further Analysis

4.6.1. Regression Results Based on Different Property Rights

4.6.2. Regression Results Based on High and Non-High-Tech Enterprises

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Key List of Digital Engagement of Chinese Firms

| Category | Word Lists |

|---|---|

| Artificial Intelligence Technology | Artificial intelligence, business intelligence, image understanding, investment decision assistance system, intelligent data analysis Analytics, intelligent robots, machine learning, deep learning, semantic search, biometrics, face recognition, voice recognition, identity verification, autonomous driving, natural language processing |

| Blockchain Technology | Blockchain, digital currency, distributed computing, differential privacy technology, intelligent financial contracts |

| Cloud Computing Technology | Cloud computing, stream computing, graph computing, memory computing, multi-party secure computing, brain-like computing, green colour computing, cognitive computing, fusion architecture, billion level concurrency, exabyte level storage, internet of things, information physical system |

| Big Data Technology | Big data, data mining, text mining, data visualisation, heterogeneous data, credit reporting, enhancement reality, mixed reality, virtual reality |

| Digital Technology Application | Mobile internet, industrial internet, mobile network, internet medical, E-commerce, mobile pay, third party pay, NFC pay, intelligent energy, B2B, B2C, C2B, C2C, O2O, network connection, intelligent wear, intelligent agriculture, intelligent transportation, intelligent medical care, intelligent customer service, intelligent home, intelligent investment advisory, intelligent cultural tourism, intelligent environmental protection, intelligent grid, intelligent marketing, digital marketing, unmanned retail, internet finance, digital finance, Fintech, quantitative finance, open banking |

Appendix B. Sample Cleaning Process

| Firm-Year Observations | ||

| 1 | Initial sample of Chinese A-share listed firms (2013–2021) | 41,258 |

| 2 | Less: Observations from financial firms | (3102) |

| 38,156 | ||

| 3 | Less: ST and *ST firm-year observations | (2845) |

| 35,311 | ||

| 4 | Less: Observations with missing data for key variables | (8742) |

| Final Sample | 26,569 |

References

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Del Vecchio, P.; Oropallo, E.; Secundo, G. Blockchain technology design in accounting: Game changer to tackle fraud or technological fairy tale? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 1566–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Li, X.; Maex, S.A.; Shi, W. The audit implications of cloud computing. Account. Horiz. 2020, 34, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanina, T.; Ranta, M.; Dumay, J. Blockchain in accounting research: Current trends and emerging topics. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 1507–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.A.; Williams, L.T. Evaluating company adoptions of blockchain technology: How do management and auditor communications affect nonprofessional investor judgments? J. Account. Public Policy 2021, 40, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knechel, W.R. The future of assurance in capital markets: Reclaiming the economic imperative of the auditing profession. Account. Horiz. 2021, 35, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagilienė, L.; Klovienė, L. Motivation to use big data and big data analytics in external auditing. Manag. Audit. J. 2019, 34, 750–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyball, M.C.; Seethamraju, R. Client use of blockchain technology: Exploring its (potential) impact on financial statement audits of Australian accounting firms. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 1656–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar]

- Onjewu, A.K.E.; Walton, N.; Koliousis, I. Blockchain agency theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 191, 122482. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.; Liu, X.; Ma, C.; Zhuo, Y. Blockchain technology adoption and accounting information quality. Account. Financ. 2023, 63, 4125–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Shiwakoti, R.K.; Jarvis, R.; Mordi, C.; Botchie, D. Accounting and auditing with blockchain technology and artificial Intelligence: A literature review. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2023, 48, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardo, A.; Corsi, K.; Varma, A.; Mancini, D. Exploring blockchain in the accounting domain: A bibliometric analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 204–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kend, M.; Nguyen, L.A. Big data analytics and other emerging technologies: The impact on the Australian audit and assurance profession. Aust. Account. Rev. 2020, 30, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manita, R.; Elommal, N.; Baudier, P.; Hikkerova, L. The digital transformation of external audit and its impact on corporate governance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xing, M. Enterprise digital transformation and audit pricing. Audit. Res. 2021, 3, 62–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Huo, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liang, F.; Mardani, A. Digitalization generates equality? Enterprises’ digital transformation, financing constraints, and labor share in China. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 163, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, D.; Dong, H.; Fu, Q. Blockchain development and corporate performance in China: The role of ownership. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 3090–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, M.; Shahab, Y.; Lu, Y. Confucianism and auditor changes: Evidence from China. Manag. Audit. J. 2022, 37, 625–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gietzmann, M.; Grossetti, F. Blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies: Where is the accounting? J. Account. Public Policy 2021, 40, 106881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Kiel, D.; Voigt, K.I. What drives the implementation of Industry 4.0? The role of opportunities and challenges in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, M.Z.; Alsabban, A. Industry-4.0-enabled digital transformation: Prospects, instruments, challenges, and implications for business strategies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Schniederjans, D.G.; Schniederjans, M. Establishing the use of cloud computing in supply chain management. Oper. Manag. Res. 2017, 10, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Gaur, J. Testing the adoption of blockchain technology in supply chain management among MSMEs in China. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025, 350, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, A.K.; Zo, H.; Chiravuri, A. Digital transformation and environmental sustainability: A review and research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.; Reim, W. Reviewing literature on digitalization, business model innovation, and sustainable industry: Past achievements and future promises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ruan, C. Blockchain technology and corporate performance: Empirical evidence from listed companies in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Qu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, C. Is cloud computing the digital solution to the future of banking? J. Financ. Stab. 2022, 63, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimani, A.; Willcocks, L. Digitisation, ‘Big Data’and the transformation of accounting information. Account. Bus. Res. 2014, 44, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo Van, H.; Abu Afifa, M.; Saleh, I. Accounting information systems and organizational performance in the cloud computing era: Evidence from SMEs. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 64, 3173–4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wang, T.; Yen, J.C. Opportunities or Challenges? Audit Risk and Blockchain Disclosures in 10-K Filings. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2024, 43, 131–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, D.D.; Sims, A. From the abacus to enterprise resource planning: Is blockchain the next big accounting tool? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2023, 36, 24–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Li, M.; Shan, Y.G.; Ye, A. Does corporate digitalisation moderate real earnings management? Account. Financ. 2024, 64, 4157–4196. [Google Scholar]

- Wen 2024, H.; Fang, J.; Gao, H. How FinTech improves financial reporting quality? Evidence from earnings management. Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, M.G. Drivers of the use and facilitators and obstacles of the evolution of big data by the audit profession. Account. Horiz. 2015, 29, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Michas, P.N.; Russomanno, D. The impact of audit committee information technology expertise on the reliability and timeliness of financial reporting. Account. Rev. 2020, 95, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Rezaee, Z.; Xue, L.; Zhang, J.H. The association between information technology investments and audit risk. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 30, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilifsen, A.; Kinserdal, F.; Messier, W.F., Jr.; McKee, T.E. An exploratory study into the use of audit data analytics on audit engagements. Account. Horiz. 2020, 34, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahel, J.P.; Titera, W.R. Consequences of big data and formalization on accounting and auditing standards. Account. Horiz. 2015, 29, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.Y.; Lettau, M.; Malkiel, B.G.; Xu, Y. Have individual stocks become more volatile? An empirical exploration of idiosyncratic risk. J. Financ. 2001, 56, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D. How do financing constraints affect firms’ equity volatility? J. Financ. 2018, 73, 1139–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Chernobai, A.; Wahrenburg, M. Information asymmetry around operational risk announcements. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 48, 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M. Resolving information asymmetry through contractual risk sharing: The case of private firm acquisitions. J. Account. Res. 2020, 58, 1203–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Shi, W.; Jiang, F. Cheap Talk? Strategy Disclosure Intensity, Corporate Risk-Taking and Financial Performance. Br. J. Manag. 2024, 36, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grego, M.; Magnani, G.; Denicolai, S. Transform to adapt or resilient by design? How organizations can foster resilience through business model transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G. Blockchain-driven operation strategy of financial supply chain under uncertain environment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 2982–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, V.L., III; Luger, J.; Schmitt, A.; Xin, K.R. Corporate decline and turnarounds in times of digitalization. Long Range Plan. 2024, 57, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y. The effect of digital transformation on real economy enterprises’ total factor productivity. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 85, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xian, Y. Does Digital Transformation Affect Earnings Management Choices? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Enterprise digital transformation and capital market performance: Empirical evidence from stock liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Eckles, D.L.; Hoyt, R.E.; Miller, S.M. Reprint of: The impact of enterprise risk management on the marginal cost of reducing risk: Evidence from the insurance industry. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 49, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xia, X.; Jin, S. Audit fees for big data, blockchain and listed companies. Audit. Stud. 2020, 216, 68–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.W.; Wu, M.C. Business type, industry value chain, and R&D performance: Evidence from high-tech firms in an emerging market. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, A.; Zhang, Y. The effect of enterprise digital transformation on audit efficiency—Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 201, 123215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, N.M.; Subramaniam, N.; Van Staden, C.J. Corporate governance implications of disruptive technology: An overview. Br. Account. Rev. 2019, 51, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Chen, Y. How blockchain technology affects the future of auditing-a technological innovation and industry life cycle perspective. Audit. Res. 2019, 2, 3–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, M.P.; Brender, N. How do the current auditing standards fit the emergent use of blockchain? Manag. Audit. J. 2021, 36, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R.; Gull, A.A.; Shahab, Y.; Derouiche, I. Do financial performance indicators predict 10-K text sentiments? An application of artificial intelligence. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 61, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Hussain, T.; Wang, P.; Zhong, M.; Kumar, S. Business groups and environmental violations: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 85, 102459. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, Y.; Wang, P.; Tauringana, V. Sustainable development and environmental ingenuities: The influence of collaborative arrangements on environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ye, Z.; Liu, J.; Nadeem, M. Social trust, environmental violations, and remedial actions in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 198, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Auditor behavior | AuditFee | Natural logarithm of the audit expenses of listed companies. |

| AuditOp | Dummy variable equals to 1 if the firm has standard unqualified audit opinion and 0 if otherwise. | |

| Independent variables | ||

| Enterprise cloud computing, blockchain technology application | CLBL1 | Dummy variable equals to 1 if the firm uses cloud computing and blockchain technology and 0 if otherwise. |

| CLBL2 | Natural logarithm of the word frequency plus one. | |

| Moderating variable | ||

| Moderating variable Enterprise risk assumption | Risk | Profit volatility. |

| Control Variables | ||

| Firm size | Size | The natural logarithm of the total company assets. |

| Leverage level | Lev | Total liabilities divided by total assets. |

| Profitability | Roe | Net income divided by the shareholder’s equity. |

| Company growth | TobinQ | The ratio of the market value of the company to the total assets. |

| CEO duality | Dual | Dummy variable equals to 1 if the chairman of the board and the general manager of the company are the same person and 0 if otherwise. |

| Book market value ratio | Bm | The ratio of the book value to the firm’s market value. |

| Big Four audit firms | Big4 | Dummy variable equals to 1 if firm has been audited by Big Four accounting firms and 0 if otherwise. |

| Inventory ratio | Inv | Ratio of inventory to total assets. |

| Share ratio of institutional investors | Inst | Shareholding ratio of institutional investors in the firms. |

| Equity concentration | Top1 | The shareholding ratio of top 1% largest shareholder in the firms. |

| Variables | N | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Med | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuditFee | 26,569 | 13.873 | 0.675 | 12.612 | 13.766 | 16.225 |

| AuditOp | 26,569 | 0.968 | 0.175 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| CLBL1 | 26,569 | 0.341 | 0.474 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CLBL2 | 26,569 | 0.571 | 0.969 | 0 | 0 | 3.912 |

| Size | 26,569 | 22.234 | 1.300 | 19.887 | 22.048 | 26.175 |

| Lev | 26,569 | 0.419 | 0.205 | 0.057 | 0.409 | 0.897 |

| Roe | 26,569 | 0.064 | 0.133 | −0.647 | 0.074 | 0.362 |

| TobinQ | 26,569 | 2.122 | 1.435 | 0.859 | 1.667 | 9.471 |

| Dual | 26,569 | 0.295 | 0.456 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bm | 26,569 | 1.075 | 1.462 | 0.001 | 0.642 | 30.560 |

| Big4 | 26,569 | 0.059 | 0.236 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Inv | 26,569 | 0.138 | 0.128 | 0.0002 | 0.108 | 0.687 |

| Inst | 26,569 | 0.378 | 0.239 | 0.0002 | 0.384 | 0.880 |

| AuditFee | AuditOp | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| CLBL1 | 0.017 *** | 0.307 *** |

| (3.05) | (3.16) | |

| Size | 0.338 *** | 0.344 *** |

| (33.09) | (6.17) | |

| Lev | 0.133 *** | −2.833 *** |

| (4.33) | (−12.24) | |

| ROE | −0.174 *** | 3.730 *** |

| (−9.76) | (20.74) | |

| TobinQ | 0.004 | −0.183 *** |

| (1.56) | (−6.97) | |

| Dual | 0.002 | 0.071 |

| (0.24) | (0.80) | |

| BM | −0.021 *** | −0.202 *** |

| (−3.98) | (−4.70) | |

| Big4 | 0.285 *** | 0.045 |

| (7.34) | (0.21) | |

| INV | −0.050 | 2.171 *** |

| (−1.10) | (5.90) | |

| INST | −0.024 | 0.020 |

| (−1.49) | (0.09) | |

| Top1 | −0.095 | 2.486 *** |

| (−1.59) | (7.36) | |

| Constant | 5.883 *** | −2.476 * |

| (22.15) | (−1.91) | |

| Year | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,569 | 26,565 |

| Adj R2 | 0.550 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.231 |

| AuditFee | AuditOp | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| CLBL2 | 0.013 *** | 0.164 *** | ||

| (3.04) | (3.09) | |||

| L1.CLBL1 | 0.007 ** | 0.296 *** | ||

| (2.14) | (2.80) | |||

| Size | 0.337 *** | 0.323 *** | 0.343 *** | 0.351 *** |

| (32.92) | (27.93) | (6.16) | (5.79) | |

| Lev | 0.133 *** | 0.129 *** | −2.832 *** | −2.574 *** |

| (4.33) | (3.97) | (−12.24) | (−9.93) | |

| ROE | −0.174 *** | −0.142 *** | 3.727 *** | 3.968 *** |

| (−9.71) | (−7.88) | (20.74) | (20.17) | |

| TobinQ | 0.004 | −0.000 | −0.181 *** | −0.134 *** |

| (1.56) | (−0.14) | (−6.90) | (−4.45) | |

| Dual | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.070 | 0.115 |

| (0.28) | (0.37) | (0.79) | (1.19) | |

| BM | −0.021 *** | −0.020 *** | −0.201 *** | −0.202 *** |

| (−3.93) | (−3.90) | (−4.67) | (−4.35) | |

| Big4 | 0.285 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.050 | −0.094 |

| (7.34) | (7.01) | (0.23) | (−0.42) | |

| INV | −0.050 | −0.039 | 2.148 *** | 1.895 *** |

| (−1.11) | (−0.82) | (5.85) | (4.67) | |

| INST | −0.023 | −0.037 ** | 0.030 | 0.040 |

| (−1.46) | (−2.07) | (0.13) | (0.16) | |

| Top1 | −0.093 | −0.082 | 2.509 *** | 2.454 *** |

| (−1.55) | (−1.29) | (7.42) | (6.58) | |

| Constant | 5.904 *** | 6.230 *** | −2.436 * | −3.138 ** |

| (22.16) | (21.05) | (−1.88) | (−2.24) | |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,569 | 22,140 | 26,565 | 22,137 |

| Adj R2 | 0.550 | 0.511 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.231 | 0.228 | ||

| AuditFee | AuditOp | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | (4) | (3) | (4) | |

| CLBL1 | 0.019 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.140 *** |

| (3.25) | (5.26) | (2.77) | (3.23) | |

| Size | 0.341 *** | 0.381 *** | 0.145 *** | 0.155 *** |

| (32.52) | (24.58) | (5.62) | (6.21) | |

| Lev | 0.135 *** | 0.117 *** | −1.284 *** | −1.327 *** |

| (4.27) | (2.63) | (−11.88) | (−12.79) | |

| ROE | −0.180 *** | −0.370 *** | 2.037 *** | 2.010 *** |

| (−10.02) | (−6.74) | (21.46) | (22.06) | |

| TobinQ | 0.003 | 0.017 *** | −0.098 *** | −0.093 *** |

| (1.27) | (2.49) | (−7.57) | (−7.46) | |

| Dual | −0.001 | 0.040 *** | 0.014 | 0.038 |

| (−0.09) | (3.71) | (0.33) | (0.94) | |

| BM | −0.022 *** | −0.014 | −0.075 *** | −0.087 *** |

| (−4.15) | (−1.54) | (−3.53) | (−4.27) | |

| Big4 | 0.284 *** | 0.588 *** | −0.016 | 0.033 |

| (7.32) | (19.74) | (−0.16) | (0.35) | |

| INV | −0.067 | −0.203 *** | 0.891 *** | 0.912 *** |

| (−1.41) | (−4.15) | (5.20) | (5.50) | |

| INST | −0.022 | −0.051 | 0.019 | 0.043 |

| (−1.37) | (−1.45) | (0.18) | (0.43) | |

| Top1 | −0.101 | −0.100 * | 1.022 *** | 1.029 *** |

| (−1.63) | (−1.85) | (6.70) | (6.97) | |

| Constant | 6.098 *** | 5.363 *** | −0.577 | −0.790 |

| (25.80) | (15.11) | (−0.99) | (−1.35) | |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| N | 26,569 | 26,569 | 26,565 | 26,565 |

| Adj R2 | 0.546 | 0.631 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.247 | 0.233 | ||

| First Stage | Second Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CLBL1 | AuditFee | AuditOp | |

| IntDev.IV | 0.187 *** | ||

| (15.21) | |||

| CLBL1 | 0.417 *** | 1.714 *** | |

| (13.84) | (4.61) | ||

| Size | 0.054 *** | 0.360 *** | 0.080 *** |

| (8.32) | (93.30) | (2.59) | |

| Lev | −0.051 * | 0.137 *** | −1.342 *** |

| (−1.57) | (7.76) | (−12.47) | |

| Roe | −0.039 | −0.359 *** | 1.959 *** |

| (−1.31) | (−16.30) | (20.00) | |

| TobinQ | 0.010 *** | 0.012 *** | −0.105 *** |

| (2.66) | (5.17) | (−7.91) | |

| Dual | 0.061 *** | 0.013 ** | −0.030 |

| (5.60) | (2.00) | (−0.68) | |

| Bm | −0.032 *** | −0.002 | 0.036 *** |

| (−5.58) | (−0.52) | (−1.49) | |

| Big4 | −0.056 ** | 0.595 ** | 0.091 |

| (−2.40) | (48.30) | (0.93) | |

| Inv | −0.217 *** | −0.127 *** | 1.092 *** |

| (−5.52) | (−5.45) | (6.17) | |

| Inst | −0.096 *** | −0.013 | 0.074 |

| (−3.90) | (−0.92) | (0.72) | |

| Top1 | −2.44 *** | −0.018 | 1.145 *** |

| (−6.23) | (−0.87) | (7.45) | |

| Constant | −0.768 *** | 5.648 *** | 0.175 |

| (−10.10) | (73.15) | (0.27) | |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,569 | 26,569 | 26,565 |

| R2 | 0.218 | 0.569 | 0.240 |

| Wald F | 231.455 *** | ||

| AuditFee | AuditOp | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| CLBL1 | 0.018 *** | 0.449 *** |

| (3.16) | (4.00) | |

| Risk | 0.692 *** | −8.149 *** |

| (9.50) | (−12.27) | |

| CLBL1 * Risk | 0.193 * | −4.622 *** |

| (1.87) | (−5.00) | |

| Size | 0.353 *** | 0.318 *** |

| (35.13) | (5.42) | |

| Lev | 0.090 *** | −2.844 *** |

| (3.10) | (−11.76) | |

| ROE | −0.116 *** | 3.492 *** |

| (−6.15) | (17.62) | |

| TobinQ | 0.003 | −0.193 *** |

| (1.22) | (−7.08) | |

| Dual | 0.001 | 0.076 |

| (0.21) | (0.81) | |

| BM | −0.016 *** | −0.193 *** |

| (−3.00) | (−4.24) | |

| Big4 | 0.291 *** | 0.204 |

| (7.17) | (0.84) | |

| INV | −0.005 | 1.881 *** |

| (−0.11) | (4.81) | |

| INST | −0.004 | −0.119 |

| (−0.26) | (−0.50) | |

| Top1 | −0.055 | 2.154 *** |

| (−0.98) | (6.14) | |

| Constant | 5.567 *** | −1.043 |

| (21.68) | (−0.74) | |

| Year | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes |

| N | 26,569 | 26,569 |

| Adj R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.561 | 0.232 |

| AuditFee | AuditOp | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| State-Owned Enterprises | Non-State-Owned Enterprises | State-Owned Enterprises | Non-State-Owned Enterprises | |

| CLBL1 | 0.002 | 0.021 *** | 0.568 ** | 0.275 ** |

| (0.23) | (3.08) | (2.46) | (2.52) | |

| Size | 0.340 *** | 0.301 *** | 0.442 *** | 0.391 *** |

| (18.71) | (25.35) | (3.72) | (5.89) | |

| Lev | −0.027 | 0.113 *** | −3.190 *** | −2.832 *** |

| (−0.51) | (3.10) | (−6.35) | (−10.61) | |

| ROE | −0.087 *** | −0.178 *** | 3.473 *** | 3.695 *** |

| (−2.97) | (−8.44) | (9.12) | (17.57) | |

| TobinQ | −0.000 | 0.002 | −0.166 *** | −0.194 *** |

| (−0.06) | (0.80) | (−2.71) | (−6.48) | |

| Dual | 0.016 | −0.003 | −0.009 | 0.195 ** |

| (1.39) | (−0.33) | (−0.03) | (2.02) | |

| BM | −0.009 | −0.010 | −0.013 | −0.480 *** |

| (−1.15) | (−1.54) | (−0.14) | (−8.42) | |

| Big4 | 0.248 *** | 0.310 *** | 0.346 | −0.034 |

| (5.30) | (5.57) | (0.76) | (−0.13) | |

| INV | −0.042 | −0.012 | 2.727 *** | 2.149 *** |

| (−0.52) | (−0.22) | (3.26) | (5.06) | |

| INST | −0.019 | −0.021 | −0.449 | −0.121 |

| (−0.64) | (−1.18) | (−0.78) | (−0.47) | |

| Top1 | 0.243 ** | −0.107 | 1.739 ** | 2.671 *** |

| (2.30) | (−1.56) | (2.39) | (6.68) | |

| Constant | 5.799 *** | 6.647 *** | −4.113 | −3.101 * |

| (11.83) | (21.69) | (−1.55) | (−1.88) | |

| Experience p value | 0.075 * | 0.028 ** | ||

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 8643 | 17,926 | 8246 | 17,922 |

| Adj R2 | 0.453 | 0.592 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.229 | 0.255 | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuditFee | AuditFee | AuditOp | AuditOp | |

| High-Tech Enterprises | Non-High-Tech Industries | High-Tech Enterprises | Non-High-Tech Enterprises | |

| CLBL1 | 0.016 ** | 0.009 | 0.476 *** | 0.097 |

| (2.07) | (1.11) | (3.68) | (0.65) | |

| Size | 0.315 *** | 0.348 *** | 0.314 *** | 0.395 *** |

| (25.17) | (19.91) | (4.26) | (4.52) | |

| Lev | 0.162 *** | 0.107 ** | −4.126 *** | −1.013 *** |

| (4.39) | (2.11) | (−13.51) | (−2.77) | |

| ROE | −0.162 *** | −0.170 *** | 3.091 *** | 4.658 *** |

| (−7.27) | (−6.12) | (13.33) | (15.80) | |

| TobinQ | 0.000 | 0.010 ** | −0.161 *** | −0.198 *** |

| (0.12) | (2.21) | (−4.62) | (−4.80) | |

| Dual | 0.003 | −0.000 | 0.127 | −0.047 |

| (0.32) | (−0.02) | (1.11) | (−0.33) | |

| BM | −0.013 | −0.019 *** | −0.089 | −0.318 *** |

| (−1.38) | (−3.19) | (−1.26) | (−5.46) | |

| Big4 | 0.243 *** | 0.297 *** | 0.246 | −0.078 |

| (5.02) | (5.16) | (0.67) | (−0.28) | |

| INV | 0.095 | −0.155 *** | 2.468 *** | 1.717 *** |

| (1.15) | (−3.04) | (3.70) | (3.72) | |

| INST | −0.013 | −0.040 | 0.230 | −0.247 |

| (−0.63) | (−1.61) | (0.76) | (−0.69) | |

| Top1 | −0.129 * | −0.106 | 2.958 *** | 1.831 *** |

| (−1.65) | (−1.37) | (6.23) | (3.73) | |

| Constant | 6.666 *** | 5.816 *** | −2.611 | −3.988 ** |

| (24.03) | (14.21) | (−1.48) | (−2.05) | |

| Experience p value | 0.085 * | 0.035 ** | ||

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 15,835 | 10,734 | 15,830 | 10,730 |

| Adj R2 | 0.528 | 0.534 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.240 | 0.240 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, H.-X.; Ma, S.; Gao, X.; Wang, T.; Li, Y. Crafting Resilient Audits: Does Distributed Digital Technology Influence Auditor Behavior in the Age of Digital Transformation? Sustainability 2026, 18, 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020623

Li H-X, Ma S, Gao X, Wang T, Li Y. Crafting Resilient Audits: Does Distributed Digital Technology Influence Auditor Behavior in the Age of Digital Transformation? Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020623

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hai-Xia, Shenghui Ma, Xin Gao, Ting Wang, and Yanan Li. 2026. "Crafting Resilient Audits: Does Distributed Digital Technology Influence Auditor Behavior in the Age of Digital Transformation?" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020623

APA StyleLi, H.-X., Ma, S., Gao, X., Wang, T., & Li, Y. (2026). Crafting Resilient Audits: Does Distributed Digital Technology Influence Auditor Behavior in the Age of Digital Transformation? Sustainability, 18(2), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020623