1. Introduction

The development of generative artificial intelligence tools (GenAI) is becoming one of the most important factors transforming contemporary educational systems. This development is embedded in the broader paradigm of sustainable education, which emphasizes the need for responsible and long-term development of competences in a dynamically changing technological environment. In particular, large language models (LLMs) are gaining prominence, as they can support both teaching and learning processes across multiple dimensions. Owing to their capabilities in natural language generation, content analysis, and interactive dialogue, LLMs enable the creation of dynamic learning environments in which learners can receive immediate feedback, support in problem solving, and access to personalized educational content [

1,

2]. In the context of adult education, LLMs may support the development of self-directed learning competences by offering assistance in knowledge acquisition [

3]. However, the use of GenAI must be approached with caution and requires learners to adopt a critical perspective on its application due to ethical concerns, the risk of substantive errors, and its potential impact on learners’ cognitive autonomy [

4,

5]. This perspective is consistent with the principles of sustainable education, which emphasize reflective and autonomy supporting use of digital tools. Nevertheless, the potential of LLMs as tools supporting education is undeniable and increasingly highlighted by researchers.

Against the backdrop of the literature review, several questions emerge: Is the use of GenAI in adult education evenly distributed? What determines the scope of GenAI use in adult education? Research conducted by numerous scholars points to the significant role of digital skills, which condition users’ ability to select, analyze, and critically interpret content [

6,

7,

8]. Psychosocial factors are also important, including personal innovativeness, understood as an individual’s propensity to experiment with new technological solutions [

9]. Personal innovativeness fosters positive attitudes toward technology, influences perceptions of its usefulness, and encourages more advanced forms of use [

10].

Despite the growing interest in the impact of GenAI on learning processes, empirical research on the use of generative AI tools in education remains unevenly developed. Existing studies have focused primarily on issues of access to technology, initial adoption, and attitudes toward AI, most often among students and younger learners. As a result, considerably less attention has been paid to adult learners and to the diversity of ways in which GenAI is used in educational contexts. In particular, there is a lack of empirical research that adopts an integrated perspective on digital competences and personal innovativeness as coexisting resources shaping adults’ capacity to use generative AI tools. This gap limits our ability to explain the mechanisms through which generative AI may, on the one hand, support lifelong learning and, on the other, contribute to the emergence of new forms of digital stratification among adult learners.

The aim of this article is therefore to identify the mechanisms that drive differentiated use of ChatGPT among adult learners in Poland, with particular emphasis on the role of digital competences and personal innovativeness. The study addresses an important research gap and provides an informational basis that may be used in the development of educational policy strategies concerning the responsible use of generative AI tools in lifelong learning.

The article comprises both theoretical and empirical components and focuses on the determinants of differentiated ChatGPT use among adult users in Poland.

Section 1 presents the research background and the motivation for analyzing the role of digital competences and personal innovativeness in the adoption of generative artificial intelligence tools. The theoretical part (

Section 2) discusses key concepts, including digital skills (DS), personal innovativeness (PI), and use of ChatGPT (UC), and presents the conceptual model and research hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the methodology applied, including the construction of the research instrument, data collection procedures, sample characteristics, and data analysis methods.

Section 4 presents the results of the CFA and SEM analyses, together with hypotheses testing and an analysis of gender moderation.

Section 5 provides a discussion of the findings and their implications.

Section 6 and

Section 7 discusses the practical implications for education and study’s limitations and directions for future research. The

Section 8 present the conclusions.

This paper provides three main contributions:

it offers an empirical model explaining the differentiated use of ChatGPT in adult education by jointly considering digital skills and personal innovativeness,

it identifies a mechanism of stratified GenAI use, demonstrating that access to the tool alone does not translate into advanced application without sufficient competence-related resources,

it reveals gender-based variation in the strength of these relationships, highlighting the need to incorporate a gender perspective into research on LLM adoption in adult education.

These contributions situate the study within a broader discussion on competence inequalities and the conditions for informed and autonomous use of GenAI in lifelong learning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Skils in Adults’ Education

Digital skills can be defined as the technical ability to operate digital tools and devices, enabling users to select, analyze, and interpret information, as well as to create content in a digital environment [

11]. In contemporary research, however, there has been a shift away from a unidimensional understanding of DS as solely technical proficiency toward a multidimensional definition. In this perspective, DS are understood as a set of integrated resources, such as knowledge, skills, and attitudes, that are necessary for effective, critical, and responsible use of technology in everyday, professional, and civic life [

12,

13]. These skills extend beyond the mere technical operation of digital tools and also encompass cognitive, social, and ethical competences that enable individuals to select, analyze, and interpret information and to create content in digital environments [

12,

14]. Digital skills can be categorized along several dimensions, including technical and operational skills, cognitive and informational skills, social and communication skills, and digital content creation skills [

12,

15]. As noted by Gazzola et al. [

16], a key challenge in the digital economy is the shift from passive possession of skills toward consumer empowerment, which enables individuals to act autonomously and make sustainable decisions. Tomczyk [

17] further argues that mature digital competences must include a reflective component regarding the impact of media, which is essential for conscious functioning in an environment saturated with AI driven algorithms.

The theoretical foundation for the categorization of digital competences is provided by frameworks such as the European Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp), which precisely operationalizes DS by dividing them into five areas: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving [

14]. DigComp 2.1 extends this structure by introducing eight proficiency levels, ranging from basic to highly specialized [

13,

18]. The rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICT) requires these frameworks to be continuously updated in order to account for emerging trends, including the use of social media, mobile technologies, and AI [

19,

20].

In the context of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), the distinction between functional skills, understood as the operational use of systems, and critical skills, referring to an understanding of how technologies function and the ability to verify their outputs, appears to be particularly important, as highlighted by the ySKILLS framework [

15]. Deficits in critical competences constitute a primary source of so-called user stratification, or usage gap, whereby individuals with lower levels of competence are limited to basic content consumption, while more advanced users leverage the potential of AI for creative and analytical tasks [

15,

21].

The specificity of digital skills (DS) in the context of adult education relates to continuous learning and the socio-economic integration of individuals who have often already completed formal education and encounter specific barriers. Eynon [

18] notes that policies addressing DS for adults frequently adopt an instrumental orientation focused on labor market needs, while neglecting the broader educational perspective necessary for developing critical thinking skills. In the context of adult education, several key conditions are particularly relevant.

The first is the necessity of lifelong learning in the digital domain, driven by technological development, which requires adults to continuously update their competences through upskilling and reskilling in order to avoid a digital capability gap that is widening between labor market demands and workforce skills [

22,

23].

Another important factor is digital maturity. Laaber et al. [

24] define digital maturity as a set of abilities and attitudes that enable responsible use of technology. Research shows that the level of digital maturity is a strong predictor of the acceptance of new technological solutions. Individuals with higher digital maturity exhibit lower levels of technology related anxiety and greater readiness for innovation [

13,

22].

Equally important is the specificity of adult motivation. Educational decisions made by adults, such as the choice of online learning modes, unlike those of younger learners, are not shaped by social influence. Instead, they are influenced by personal beliefs, including performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions [

25]. This implies that adults will adopt ChatGPT only if they perceive that they possess sufficient skills for the tool to genuinely improve their work outcomes at an acceptable level of effort.

Publications on digital competences in adult education are less numerous than those focusing on younger populations. Public policies addressing DS for adults often concentrate on operational, evaluative, and strategic skills that span a continuum from basic to specialized levels [

18]. From the perspective of adult education, research indicates that individuals in older age groups, defined as 25 to 64 years, demonstrate lower levels of basic digital skills, estimated at 60%, compared to 82% among those aged 16 to 24 in Europe [

20]. Adults frequently acquire digital skills through experimentation and digital informal learning, which is unstructured, self-directed, flexible, and not tied to a traditional classroom environment [

12,

18]. In the case of adults with lower levels of formal education, a key challenge lies in identifying innovative methods to reach the most vulnerable groups and in ensuring flexible and adequate professional development for adult educators [

22,

26].

The overarching goal of adult education is to support individuals in continuously expanding their digital knowledge and skills in order to remain competitive, while also reducing the gap between those who are digitally proficient and those who are not, commonly referred to as the digital divide [

26,

27]. Lifelong learning in the digital context has become a necessity, as reflected in European Union objectives that emphasize a substantial increase by 2030 in the number of adults equipped with relevant skills, including technical and vocational competences, for employment and entrepreneurship, in line with Global Goal 4.4 [

22,

26].

The literature review provides a solid theoretical foundation for Hypothesis H1, which assumes that digital skills have a positive effect on the use of ChatGPT in adult education. Adults with higher levels of digital skills are not only more inclined to adopt ChatGPT, but also use this tool in a more conscious and informed manner.

2.2. Personal Innovativeness in Adults’ Education

Personal innovativeness constitutes an important construct that has been widely examined in the literature. A useful point of departure is the most frequently cited definition of this concept, which describes it as “a person’s willingness to try out new information technologies and adopt new ideas” [

28]. According to Rogers, innovativeness refers to the degree of interest in experimenting with a new technology, service, or product, and the adoption of innovations may vary across individuals depending on their preferences [

29]. Numerous studies emphasize the importance of personal innovativeness and its associations with the acceptance and use of modern technologies. Research by various authors highlights the relevance of this construct for the utilization of advanced technologies [

30] as well as its moderating role in relationships between variables shaping the intention to adopt a given technology [

31].

Empirical evidence supports these claims. Lu et al. (2005) demonstrated that personal innovativeness has a direct and positive effect on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of mobile wireless internet services [

10]. Velverthi et al. (2024) identified a negative relationship between perceived innovativeness and perceived risk among patients, alongside a strong association between personal innovativeness and both perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness [

32]. Similarly, research by Alkadi and Abed [

33] indicates a significant influence of personal innovativeness on the intention to use AI enabled voice assistants in banking among members of Generation Z. That study also identified the impact of this variable on attitudes toward the adoption of new technologies. The authors emphasize that behavioral intentions and the adoption of AI are strongly shaped by both personal innovativeness and perceived trust [

33].

Further evidence points to a strong positive effect of personal innovativeness on self-efficacy, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and behavioral outcomes among pre-service teachers with respect to the use of GenAI in teaching [

34]. Studies conducted by Wolny et al. (2025) reveal a positive relationship between personal innovativeness and digital consumer behaviors, with gender moderating the effect of this trait on the behaviors examined [

8]. Collectively, these research findings suggest that personal innovativeness is a characteristic that, in many contexts, significantly determines human behavior across diverse groups, including consumers, patients, teachers, and younger generations.

At the same time, some studies indicate that personal innovativeness, conceptualized as a personality trait, does not play a significant role in students’ use of tools such as ChatGPT. In this line of research, scholars argue that students’ readiness to use ChatGPT appears to be shaped primarily by practical, experience-based factors rather than by individual predispositions [

35]. According to Okaily et al. (2025), innovativeness serves as a moderating variable between intention to use ChatGPT and its actual adoption among business school students in Jordan [

36]. In turn, Indrawati et al. (2025) report that personal innovativeness, together with performance expectancy, constitutes the strongest predictor of ChatGPT adoption among students, educators, and administrators in higher education institutions in Botswana [

37].

In adult education, which largely relies on learner autonomy and voluntary participation, personal innovativeness assumes particular importance. Adults’ willingness to use tools such as ChatGPT depends not only on their perceived usefulness, but also on openness to experimentation and tolerance of ambiguity. Accordingly, the literature supports Hypothesis H2, which posits that personal innovativeness has a positive effect on the use of ChatGPT in adult education.

2.3. Use of ChatGPT in Adults’ Education

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence tools (GenAI), with particular emphasis on ChatGPT, has initiated fundamental changes in the learning paradigm [

38]. ChatGPT, a chatbot based on a large language model (LLM), is capable of generating coherent and contextually appropriate text that resembles human language, which has made it a valuable resource supporting multiple aspects of everyday life [

39,

40].

In the context of adult education, which by its nature relies on a higher degree of learner autonomy and self-direction compared to education at earlier stages, AI is perceived as a tool with transformative potential [

41]. The literature indicates that adult learners use ChatGPT not only as an intelligent tutor, but primarily as a tool that enhances the efficiency of cognitive processes, enabling the personalization of learning pathways and the adjustment of learning pace to individual time constraints and professional responsibilities [

39,

40,

42]. At the same time, other sources suggest that excessive reliance on ChatGPT may lead to a range of negative outcomes, including a decline in independent thinking and problem-solving abilities, reduced creativity, limited opportunities for exploration, diminished capacity for argumentation and clear expression of opinions, and uncritical acceptance of the factual accuracy of generated content [

43,

44].

ChatGPT operates on the basis of transformer-based neural network architectures. It is important to note that its functioning does not involve knowledge in the human sense, but rather statistical prediction of subsequent sequences of tokens based on vast training datasets, which may give rise to specific issues related to reliability [

45]. These issues include:

A crucial factor in adapting to the use of ChatGPT is the digital skills of users [

7,

49]. Digital skills can be divided into functional, or technical, competences and critical competences. Functional skills relate to the practical use of technology, whereas critical skills encompass the ability to understand how technologies operate and to engage in informed analysis of digital content. In the context of ChatGPT use in adult education, critical competences form the foundation for more conscious, creative, and engaged participation in the digital society, which in turn leads to more effective and responsible use of AI tools [

15].

An equally important aspect of ChatGPT use in adult education is the previously discussed phenomenon of personal innovativeness [

28,

50]. Research indicates that an individual’s propensity to experiment with new technologies is a strong predictor not only of tool acceptance, but also of the depth and sophistication of its use. While individuals with high levels of innovativeness tend to employ AI in complex creative and analytical processes, such as critical text analysis or problem solving, users with more conservative attitudes often limit their engagement to basic functions, including language correction or simple information retrieval. In this sense, innovativeness can be understood as a filter that determines the quality of interaction with AI systems [

28,

51].

Despite enthusiastic forecasts, scholarly discourse increasingly draws attention to the risk of widening inequalities. The implementation of AI in adult education reveals a new form of the digital divide, which no longer concerns mere access to technology, but rather the ability to use it effectively [

49]. Rawas [

52] observes that although ChatGPT has the potential to empower learners, in the absence of adequate digital competences it may become a superficial or symbolic tool, leading to shallowness in the educational process. In the Polish educational context, this phenomenon is particularly salient, as levels of digital competences are highly differentiated, and the lack of systemic support for artificial intelligence may result in stratification, whereby the primary beneficiaries of technological advancements are individuals who already possess high levels of digital capital [

53].

The literature thus points to the dualistic nature of ChatGPT’s impact on adult education. On the one hand, it offers unprecedented opportunities for substantive support in the learning process; on the other hand, it may generate significant ethical and pedagogical challenges [

39,

54].

2.4. Model Development

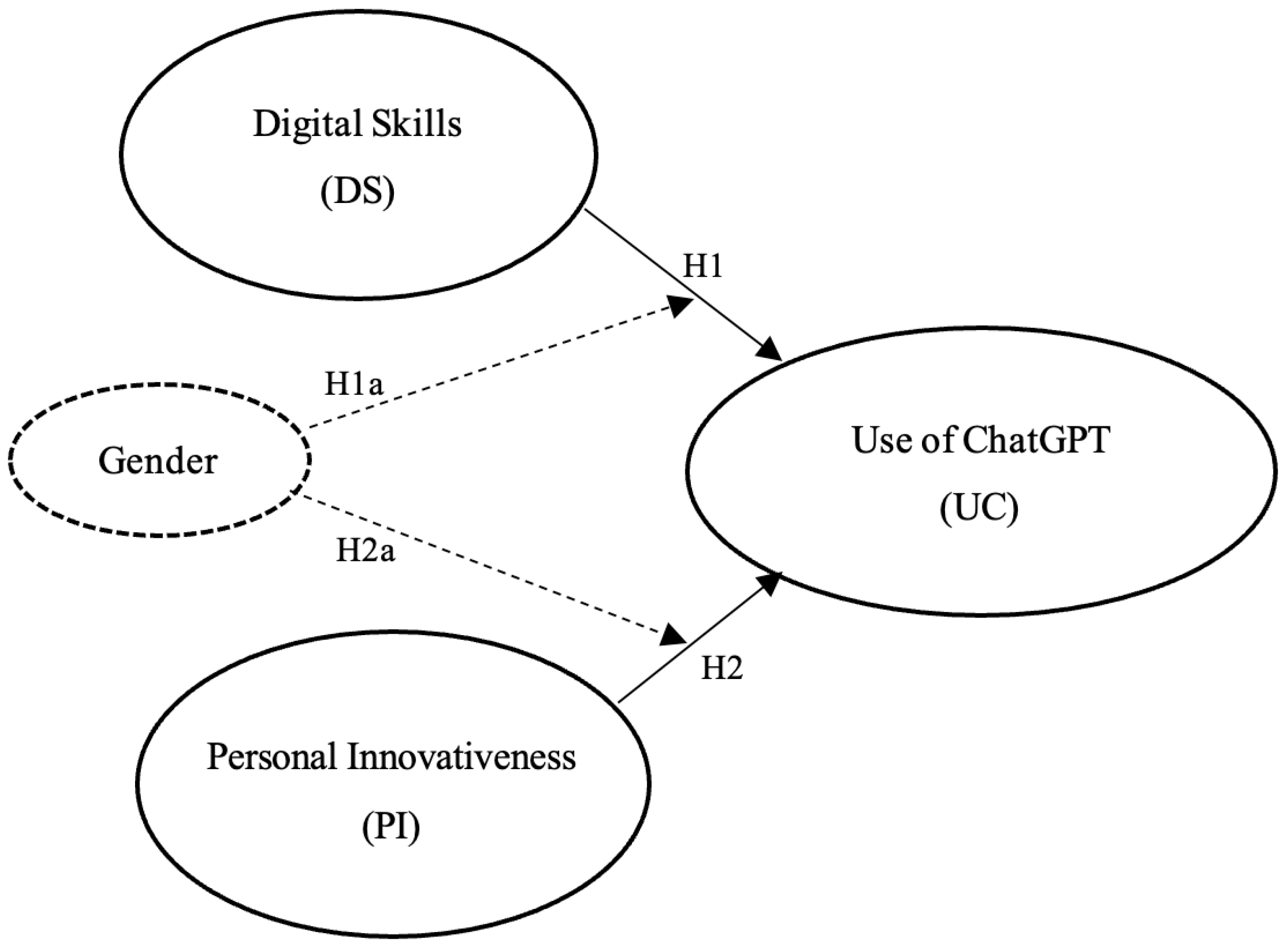

The aim of this article is to investigate how digital competences and personal innovativeness shape variation in the use of ChatGPT among users in Poland, thereby revealing differentiated approaches to AI supported education. On the basis of the literature review, a conceptual model was developed, as presented in

Figure 1. The model assumes that digital competences are a key determinant of conscious and more advanced use of artificial intelligence-based tools. Individuals who navigate the digital environment more proficiently are more likely to use ChatGPT for demanding educational tasks, such as analysis, problem solving, and content creation.

The second important component of the model is personal innovativeness, understood as a psychosocial factor influencing users’ readiness to engage with new technologies. Previous research indicates that a propensity for experimentation, tolerance of uncertainty, and openness to technological innovation significantly determine the adoption of AI based tools. The outcome variable encompasses different ways of using ChatGPT, including uses that vary in their level of advancement. The model reflects the assumption that the introduction of AI into education may deepen differences between users if their digital competences and readiness to adopt new technologies are unevenly distributed. The findings of the study will also make it possible to identify how individual differences, including those related to gender, translate into differentiated use of generative AI in educational contexts.

The following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1. Digital skills (DS) have a positive effect on the use of ChatGPT (UC).

H2. Personal innovativeness (PI) has a positive effect on the use of ChatGPT (UC).

The literature emphasizes that gender may differentiate ways of using digital technologies, even when levels of competence are comparable. These differences are often linked to distinct patterns of technological socialization, self-assessments of skills, and preferred modes of interaction with technology. As a result, gender may modify the strength of the relationships between digital competences and personal innovativeness and advanced forms of using GenAI tools. Therefore, the following additional hypotheses were formulated:

H1a. Gender moderates the strength of the relationship between digital skills (DS) and the use of ChatGPT (UC).

H2a. Gender moderates the strength of the relationship between personal innovativeness (PI) and the use of ChatGPT (UC).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Development

For the purposes of this study, the following scales were identified to measure the key constructs (

Table A1). In the case of the Digital Skills (DS) construct, items referring to core areas of digital competence were employed, including information searching and processing, communication and collaboration in digital environments, and the creation and management of digital content. These scales were adapted from the works of Helsper et al. [

15], Tzafilkou, Perifanou, and Economides [

20], as well as Perifanou and Economides [

14].

The construct of Personal Innovativeness (PI) was measured using items developed by He and Zhu [

55], which have been applied in studies on informal digital learning among students. The items used to assess the Use of ChatGPT (UC) construct were based on a scale developed and validated by Lee and Park [

53], designed to evaluate competences related to the use of tools based on language models.

A five-point Likert type scale was applied to measure digital competences, personal innovativeness, and the use of ChatGPT, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The questionnaire also included items capturing respondents’ characteristics, such as gender, age, level of education, employment status, and place of residence.

3.2. Data Collection

The empirical data were collected using the Computer Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) method. The selection of this approach was driven by the need to reach a geographically dispersed population of digital technology users and to efficiently collect data on digital competences, attitudes, and behaviors. By eliminating interviewer effects, the CAWI method provides a high level of standardization in the research process and ensures respondents’ anonymity, which facilitates the collection of reliable data [

56].

During the preparatory phase, both the research design and the measurement instrument underwent ethical review. An application was submitted to the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Participants at the University of Economics in Katowice to verify the compliance of the research procedure with international ethical standards. A positive opinion was obtained (Opinion No. 2/2025), confirming that the study adheres to the principles of research ethics and fully safeguards the rights and well being of participants. The research procedure was designed to exclude sensitive or intimate questions that could cause emotional discomfort, in line with the fundamental principle of non-maleficence in social science research. Throughout the study, strict adherence was maintained to the principles of voluntary participation, informed consent, and protection of respondents’ identities, ensuring full confidentiality of the collected data [

57,

58]. Subjecting the project to external ethical evaluation constitutes an important element in ensuring the credibility and scientific rigor of the analyses conducted, in accordance with the standards of professional social research [

59].

Prior to the main study, a pilot survey was conducted with a sample of 20 respondents in order to validate the online questionnaire. This process enabled the assessment of the clarity and appropriateness of the survey items from the respondents’ perspective. Based on the feedback received, editorial revisions were introduced to enhance the clarity of instructions and ensure terminological precision.

The distribution of the questionnaire in the main study was carried out via the SurveyMonkey.com platform, with data collection supervised by the Center for Research and Development of the University of Economics in Katowice. The study was conducted in the first half of 2025. A total of 1371 individuals participated, and after excluding incomplete responses, the sample was reduced to 1243 valid observations. At this stage, the structure of the sample was aligned with the Polish adult population with respect to key sociodemographic characteristics, namely gender, age, and place of residence, based on data from the Central Statistical Office. To identify the specific target population, a filtering question regarding the use of ChatGPT and engagement in learning activities was included in the questionnaire, which allowed for the selection of respondents with actual experience using the tool. The final analytical sample, subjected to detailed analysis of variation in AI use as the dependent variable in the model, consisted of 757 participants. For this group, a balanced distribution was maintained with regard to gender, age, level of education, and place of residence.

Participation in the study was voluntary and fully anonymous, with no collection of data enabling the identification of respondents. Participants were informed about the scientific objectives of the project and their right to withdraw consent at any time. The entire research process was conducted in accordance with the principles of research ethics, the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the guidelines of the ESOMAR Code of Conduct for Market and Opinion Research, ensuring researcher neutrality and data confidentiality. The collected empirical material enabled the achievement of the study’s research objectives and the verification of the proposed hypotheses.

3.3. Sample

The research sample was constructed to achieve a balanced structure in terms of gender, age, level of education, and place of residence. The study was not representative in a probabilistic sense; however, controlling for these key sociodemographic characteristics helped reduce potential structural biases and ensured that the sample was appropriate for the intended analyses. The composition of the sample reflects the diversity of adult learning pathways, which allows for a more nuanced examination of the relationships between digital skills, personal innovativeness, and the ways in which ChatGPT is used across different demographic groups. All respondents were involved in activities aimed at upgrading their qualifications, including bachelor’s and master’s degree programmes, postgraduate studies, vocational courses, and universities of the third age. Formal level of education was treated as a descriptive characteristic of respondents, whereas participation in adult learning activities constituted the inclusion criterion for the study.

Women accounted for 44.4% of the sample, while men constituted 55.6%. The largest age group comprised respondents aged 35 to 44 years, representing 23.2% of the sample, followed by those aged 25 to 34 years at 21.1% and 45 to 54 years at 18.4%. The smallest age group consisted of respondents aged 55 to 64 years, accounting for 10.8%. Most respondents held higher education qualifications at 54.2% or secondary education at 37.1%. Participants with vocational and primary education represented 6.1% and 2.6% of the sample, respectively. Nearly three quarters of respondents were economically active, while 28.8% were not employed at the time of the survey.

The largest group of respondents resided in rural areas, accounting for 36.9% of the total sample. More than one quarter of participants lived either in large urban agglomerations with populations exceeding 501 thousand or in medium sized cities with populations ranging from 51 thousand to 100 thousand. The smallest groups consisted of residents of towns with up to 50 thousand inhabitants and cities with populations between 101 thousand and 500 thousand, representing 6.2% and 2.5% of respondents, respectively.

A detailed summary of the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics is presented in

Table 1.

3.4. Methods of Analysis

To verify the measurement structure of the examined constructs and to assess the relationships between them, a set of statistical analyses based on structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied.

Prior to the main analyses, assumptions regarding the distribution of variables were examined. Multivariate normality was assessed using Mardia’s test, which revealed significant departures from normality, a phenomenon commonly observed in Likert type data [

60]. In light of these results and methodological recommendations for categorical data, the WLSMV estimator was employed in subsequent analyses, as it is particularly appropriate for polychoric correlations and ordinal variables [

61,

62].

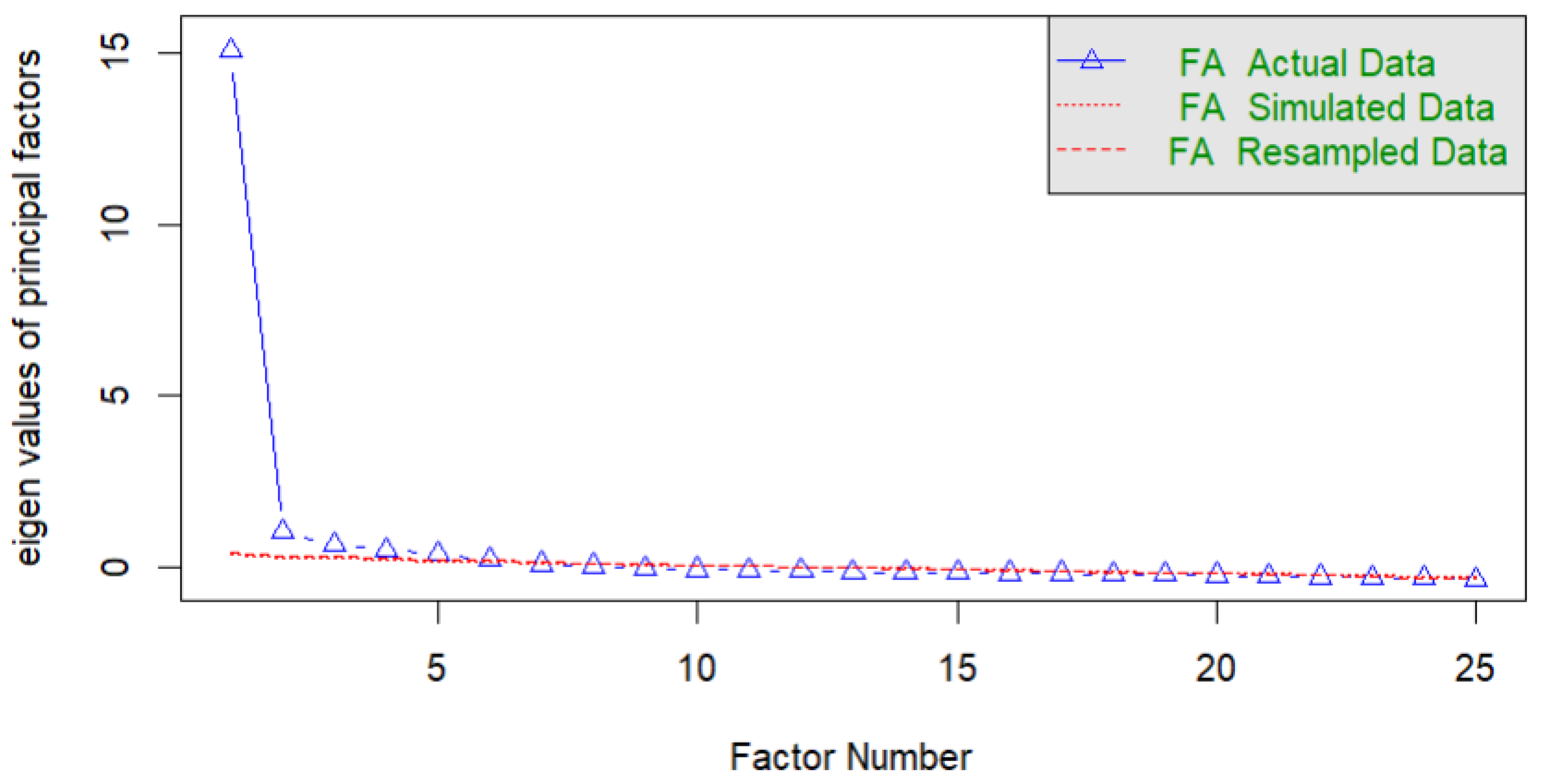

For the use of ChatGPT (UC) scale, the factor structure was evaluated using parallel analysis based on polychoric correlations, with principal axis factoring (PAF) as the extraction method. The analysis indicated that only the first factor had an eigenvalue exceeding the randomly generated value, which, in line with the classical work of Horn [

63] and more recent recommendations by Hayton et al. [

64], supports a unidimensional structure of the scale.

Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models were estimated for the three constructs: digital skills (DS), personal innovativeness (PI), and use of ChatGPT (UC). Model fit was assessed using the CFI and TLI indices, with values exceeding 0.90 considered acceptable [

65], as well as RMSEA with a 90% confidence interval, interpreted in accordance with the guidelines proposed by MacCallum et al. [

66]. The SRMR index was also used as an indicator of model fit. It should be noted that in models estimated using WLSMV and in models with a large number of indicators, RMSEA values may be inflated [

67]; therefore, this index was interpreted cautiously and in context.

To evaluate the reliability and validity of the constructed scales, several complementary indicators were applied. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and its ordinal version were calculated, adopting the conventional threshold of 0.70 as an acceptable level of reliability [

68]. In addition, McDonald’s Omega coefficient was computed [

69], as it is considered more stable and appropriate in multifactorial models [

70]. Convergent validity was assessed using Composite Reliability (CR), with values of 0.70 or higher indicating satisfactory internal consistency [

71], and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), where values of 0.50 or higher are interpreted as evidence of convergent validity [

72]. Discriminant validity was examined using both the classical Fornell–Larcker criterion and comparisons between models with freely estimated correlations and models in which correlations between constructs were constrained to 1.00 [

73].

After confirming satisfactory fit of the measurement models, the structural model was estimated, in which digital skills and personal innovativeness served as predictors of use of ChatGPT. Interpretation focused on standardized path coefficients and the R

2 value for the dependent variable, following the guidelines proposed by Hair et al. [

71], according to which an R

2 value of approximately 0.40 indicates a strong level of explained variance.

In addition, differences between women and men were examined using multigroup SEM. First, a configural model was estimated, followed by a metric model with equal factor loadings and a scalar model with equal loadings and intercepts. Differences in model fit were evaluated using chi square difference tests adjusted according to the Satorra–Bentler procedure [

74]. The results confirmed metric invariance, indicating that comparisons of structural path coefficients between groups are permissible. The lack of full scalar invariance suggests, however, that latent means should not be directly compared. Although full scalar invariance was not achieved, metric invariance was supported, indicating equivalence of factor loadings across gender groups. According to established methodological guidelines, metric invariance is sufficient to allow meaningful comparisons of structural relationships (i.e., regression paths) between latent variables across groups, whereas scalar invariance is required only for comparisons of latent means. Consequently, the lack of scalar invariance precludes direct comparisons of latent factor means between women and men but does not invalidate the comparison of structural path coefficients conducted in this study (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000 [

75]).

All statistical analyses were conducted in the R environment (version 4.5.2) [

76], using the

lavaan package [

77] for confirmatory and structural model estimation, the

psych package [

78] for reliability analyses and parallel analysis, the MVN package [

79] for assessing multivariate normality,

semTools [

80] for calculating reliability and validity indices of the measurement models, and

semPlot for model visualization. As the data were ordinal in nature, based on Likert type scales, categorical variable specifications were applied consistently across all analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis and Assessment of the Unidimensionality of the UC Scale

Prior to conducting CFA and SEM, Mardia’s test of multivariate normality was performed. The results indicated substantial departures from normality, with Mardia’s skewness of 33,780.44 and kurtosis of 137.26 (p < 0.001). Consequently, all models were estimated using the WLSMV estimator, which is appropriate for ordinal data.

Given the large number of items in the UC scale (25 items), parallel analysis based on polychoric correlations was conducted to evaluate its factor structure. The results clearly indicated a single underlying component, as only the first eigenvalue for the empirical data exceeded the randomly generated values, while subsequent eigenvalues were nearly identical to those derived from random data (

Figure 2). Accordingly, UC was treated as a unidimensional latent construct in the subsequent analyses.

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the WLSMV estimator, which is recommended for ordinal variables. The results indicate an acceptable level of model fit, with CFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.907, SRMR = 0.083, and RMSEA = 0.093 (90% CI: 0.091–0.095). The CFI and TLI values exceed the 0.90 threshold, and the SRMR remains below 0.10, meeting commonly accepted criteria for adequate fit. The elevated RMSEA value is a phenomenon frequently observed in models with a large number of observed indicators, particularly when estimated using WLSMV [

67]. Taking into account the remaining fit indices and the stability of the estimated parameters, the measurement model can be regarded as suitable for further analyses.

All items exhibited high and statistically significant factor loadings on their respective constructs (p < 0.001). For the digital skills factor, loadings ranged from 0.77 to 0.85; for personal innovativeness, from 0.81 to 0.91; and for use of ChatGPT, from 0.66 to 0.85. This indicates that the individual items are strongly associated with their corresponding latent variables and meaningfully reflect the constructs being measured.

The coefficients of determination (R2) for the items ranged from 0.44 to 0.83, with the vast majority exceeding the 0.50 threshold. This suggests that approximately 44% to over 80% of the variance in individual items is explained by the corresponding latent factors, indicating good quality of the observed indicators.

The reliability of the individual constructs was assessed using several indicators, including both classical measures of internal consistency and parameters derived from the measurement model (

Table 2).

Both Cronbach’s alpha and its version based on polychoric correlations reached very high values (α = 0.85–0.96; ordinal α = 0.88–0.97), indicating strong internal consistency of the items within each of the examined constructs. Similarly, McDonald’s omega (ω) confirmed high scale reliability, with values ranging from 0.86 to 0.97.

Composite reliability (CR) was calculated based on the factor loadings obtained from the CFA model. CR values ranged from 0.87 to 0.98 for the Digital Skills and Personal Innovativeness constructs, while for the use of ChatGPT scale the point estimate of CR was very close to 1.00 (CR = 0.99). This outcome is plausible in the case of very long scales characterized by high factor loadings and low measurement error [

81,

82].

Convergent validity was assessed using average variance extracted (AVE). All constructs achieved AVE values above the recommended threshold of 0.50, ranging from 0.63 to 0.74, indicating that the items within each scale explain a substantial proportion of variance in their corresponding latent factor.

Discriminant validity was evaluated using two complementary approaches. First, the square roots of AVE were compared with the inter factor correlations in accordance with the Fornell–Larcker criterion. For all pairs of constructs, the square root of AVE exceeded the corresponding latent correlations, indicating good theoretical distinctiveness among the examined dimensions. Second, chi square difference tests were conducted by comparing the unconstrained model with a more restrictive model in which the correlation between constructs was fixed at 1.0. In each case, the constrained model exhibited significantly poorer fit (Δχ2 = 222.76–537.67, p < 0.001), further confirming discriminant validity among the digital skills, personal innovativeness, and use of ChatGPT constructs.

In addition, correlations among the latent factors are reported in

Table 3. The constructs were moderately related, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.18 to 0.53, and the strongest association observed between use of ChatGPT and digital skills (r = 0.53). These values are clearly lower than the square roots of AVE for the respective constructs, providing additional support for discriminant validity in line with the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Overall, the results indicate that the applied measurement model demonstrates very high reliability, good convergent validity, and clearly confirmed discriminant validity.

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

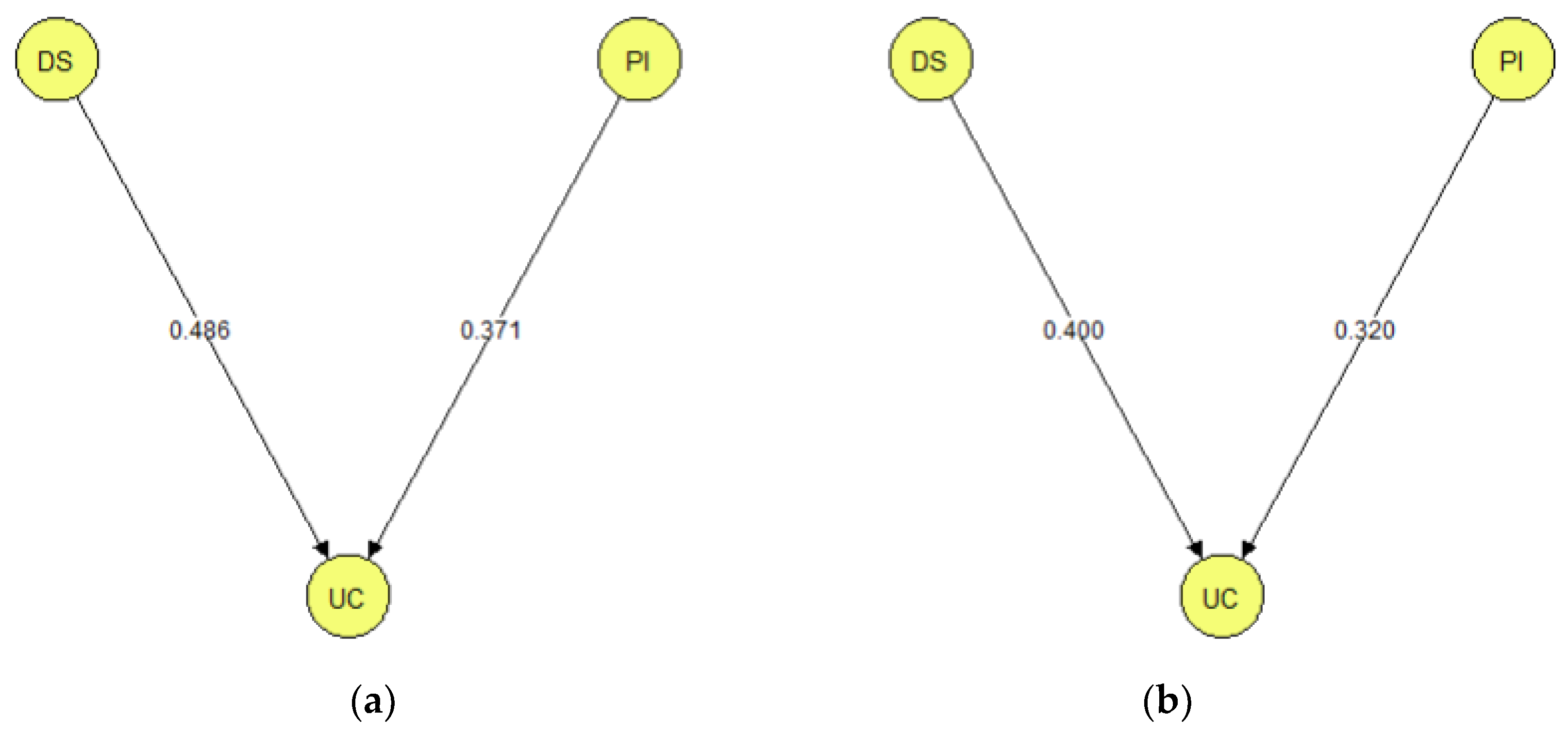

After confirming satisfactory fit of the measurement model, the structural model was estimated, in which digital skills and personal innovativeness were specified as predictors of use of ChatGPT. The structural model was estimated using the WLSMV method due to the ordinal nature of the items. Model fit remained comparable to that of the measurement model, with CFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.907, RMSEA = 0.093 (90% CI: 0.091–0.095), and SRMR = 0.083, indicating acceptable fit despite the moderately elevated RMSEA value, which is typical for models with a large number of indicators estimated using WLSMV. A graphical representation of the estimated model is provided in

Figure 3, and standardized structural effects from the SEM are reported in

Table 4.

In the structural part of the model, both predictor variables emerged as significant positive determinants of use of ChatGPT. Digital skills significantly increased the level of ChatGPT use (β = 0.46, p < 0.001), as did personal innovativeness (β = 0.37, p < 0.001). In terms of effect size interpretation, the standardized coefficient for digital skills (β = 0.46) can be classified as moderate-to-strong, while the effect of personal innovativeness (β = 0.37) represents a moderate effect. This indicates that higher levels of DS and PI are associated with greater engagement in the use of ChatGPT, with the effect of digital skills being moderately stronger than that of personal innovativeness.

The model explains approximately 41% of the variance in UC (R

2 = 0.41), which is considered a high value in psychological and technology related models [

71]. Explaining approximately 41% of the variance in ChatGPT use represents a high level of explanatory power for models of technology-related behavior, indicating that digital skills and personal innovativeness are not only statistically significant but also practically meaningful determinants of advanced AI use. The correlation between DS and PI was positive but relatively low (r = 0.18,

p < 0.001), suggesting that each predictor contributes a distinct portion of explained variance in UC.

The obtained results support both hypothesis H1, concerning the effect of digital skills on use of ChatGPT, and hypothesis H2, concerning the effect of personal innovativeness on use of ChatGPT.

4.4. Gender Differences in the SEM Model

To assess whether the relationships among digital skills, personal innovativeness, and use of ChatGPT differ between women and men, a multigroup SEM analysis was conducted using the WLSMV estimator. The procedure included tests of three successive levels of measurement invariance: configural, metric, and scalar (

Table 5).

The configural model, in which no constraints were imposed across groups, demonstrated acceptable fit, suggesting that the overall factor structure is comparable for women and men. Next, metric invariance was tested by constraining factor loadings to be equal across groups. The comparison of the configural and metric models revealed no significant difference in model fit, χ2 (3) = 0.00, p = 1.00, indicating that metric invariance was supported. This implies that the observed variables reflect the latent constructs to a comparable extent in both groups, thereby allowing for comparisons of structural path coefficients.

In the subsequent step, scalar invariance was tested by additionally constraining item intercepts to be equal across groups. The comparison of the scalar model with the configural model revealed a significant decrease in model fit, χ2 (35) = 150.71, p < 0.001. This indicates that scalar invariance was not achieved, suggesting differences in baseline levels of some indicators between genders. The lack of scalar invariance, however, does not preclude comparisons of structural paths, as such comparisons rely on the assumption of metric invariance, which was confirmed.

The multigroup model results showed that both digital skills and personal innovativeness significantly predict use of ChatGPT in both gender groups (

Figure 4 and

Table 6). The strength of these relationships, however, differed between women and men. Among men, both predictors exhibited stronger associations with the use of ChatGPT than among women. Digital skills had a particularly pronounced effect in the male group (β = 0.486), whereas this relationship was weaker among women (β = 0.400). Similarly, the effect of personal innovativeness was greater for men (β = 0.371) than for women (β = 0.320). These findings indicate gender-related differences in the magnitude of the associations linking digital skills and personal innovativeness to the use of AI tools, rather than differences in the underlying levels of these constructs.

In summary, the results indicate that the strength of the relationships between digital skills and the use of ChatGPT, as well as between personal innovativeness and the use of ChatGPT, differs across gender groups, thereby supporting hypotheses H1a and H2a.

5. Discussion

The results confirmed the proposed hypotheses: both digital skills and personal innovativeness significantly and positively predict advanced use of ChatGPT, with DS exerting a moderately stronger effect than PI. The model explains 41% of the variance in UC, while the correlation between DS and PI remains relatively low, indicating that these are two distinct yet complementary dimensions of an individual’s digital capital. Multigroup analysis further revealed that strength of the relationships between DS and PI and UC differs across gender groups, with higher standardized path coefficients observed among men than women, thereby confirming the moderating role of gender (H1a, H2a).

The obtained findings align with contemporary conceptualizations of digital competences as a multidimensional resource. The DS scale applied in this study, drawing on the work of Helsper et al. [

15] and Tzafilkou et al. [

20], captures not only basic technological operation but also information search and credibility assessment, online collaboration, and content creation. This approach is consistent with the ySKILLS framework, which conceptualizes digital competences as a complex construct integrating operational, informational, communicative, and creative skills. Systematic reviews demonstrate that higher levels of digital competences are associated with greater engagement in technologically advanced opportunities for development, including access to knowledge, educational and professional prospects, and more complex forms of activity. Research by van Deursen and van Dijk [

7] showed that individuals with higher digital competences are more likely to engage in activities yielding tangible benefits, such as financial and occupational gains, whereas those with lower competences, despite having internet access, tend to limit their use primarily to communicative and entertainment functions. An OECD report [

83] further indicates that in developed economies, workers with higher digital skills, even if they are not programmers but are proficient in advanced office and analytical tools, have access to better job opportunities and face lower risks of unemployment. Individuals with high digital competences make more frequent use of online opportunities because they possess both informational skills, enabling them to locate relevant resources, and strategic skills, allowing them to understand how digital tools can be leveraged to achieve personal goals, alongside critical thinking that helps them avoid scams and misinformation. In this context, the strong effect of DS on the use of ChatGPT for data analysis, content creation, and critical evaluation of model outputs confirms that GenAI does not replace digital competences, but rather amplifies them. Digitally competent individuals are able to use ChatGPT as a tool that strengthens their own cognitive agency.

The obtained results are consistent with research on the second and third levels of digital exclusion. Studies by van Deursen and van Dijk [

84] as well as van Dijk and Helsper [

85] demonstrate that as access to the internet becomes widespread, differences in skills and modes of use become increasingly salient (the second level divide), followed by differences in the benefits derived from technology use (the third level divide). The findings of the present study can be interpreted as an empirical illustration of these mechanisms in the domain of GenAI. Given relatively similar access to ChatGPT, it is the level of digital skills that determines whether the tool is used primarily for simple, routine queries or for complex, critical, and creative educational tasks. In this sense, GenAI becomes another arena in which differences in digital competences translate into differentiated digital dividends [

86].

The significant, albeit somewhat weaker, effect of personal innovativeness on use of ChatGPT is consistent with the classical perspective proposed by Agarwal and Prasad [

28], who conceptualize personal innovativeness in IT as a tendency toward early experimentation with new technologies and a lower aversion to uncertainty. In studies on the adoption of ChatGPT, personal innovativeness has been identified as a significant predictor of both usage intentions and actual use among students in Europe [

87] and Asia [

88]. Analyses by Al-Okaily et al. [

36] further show that more innovative individuals are more willing to integrate ChatGPT into their learning routines, and that innovativeness strengthens the effects of other factors, such as perceived usefulness, on usage behavior. In the present study, however, personal innovativeness predicts not merely frequency of use, but rather the level of advancement and agency in working with ChatGPT, including the ability to design complex prompts, integrate the tool with other systems, and identify errors and biases. This suggests that innovativeness supports not incidental use of AI, but its conscious, exploratory, and creative appropriation.

The simultaneous inclusion of digital skills and personal innovativeness allows the results to be interpreted through the lens of “digital capital”. Ragnedda and Ruiu [

89] argue that technical competences, knowledge, and attitudes toward technology form a resource that can be invested across multiple life domains, including education, work, and civic participation, while simultaneously reproducing existing social inequalities. The low correlation between digital skills and personal innovativeness observed in the present model indicates that these are two distinct components of digital capital, one rooted in skills and the other in personality-related dispositions. High levels of both are associated with the most advanced, reflective, and creative use of GenAI in learning, which in the longer term may translate into additional educational and occupational advantages.

The findings concerning gender differences further confirm that the same resources, namely digital skills and personal innovativeness, operate somewhat differently depending on gender. Among men, digital skills and personal innovativeness translate more strongly into the use of ChatGPT, as reflected in stronger structural associations, even though the relationships are significant and positive in both groups. These differences concern the strength of the associations rather than differences in the underlying levels of these resources. Qazi et al. [

90] show that gender differences in ICT use and digital skills are complex and context dependent. Men are more likely to engage in advanced, technical activities, whereas women more often use technologies for communication and collaboration. Eurostat data indicate that in younger cohorts within the European Union, women sometimes more frequently than men possess at least basic digital skills, while in older age groups the advantage shifts toward men and the gap widens [

91]. Against this background, the present results suggest that among adult learners in Poland the issue is not solely differences in the distribution of competences, but also differences in how resources such as digital skills and personal innovativeness are translated into advanced GenAI use. The same level of digital skills or innovativeness may yield a higher return in the form of advanced use of ChatGPT among men than women, pointing to an interaction between competence related factors and broader cultural and social conditions discussed in the literature on the gender digital divide [

92]. It should be emphasized that the observed gender differences refer to differences in the strength of structural relationships and do not imply direct comparisons of latent construct levels, which were not conducted due to the lack of scalar invariance.

It is important to emphasize that the dependent variable UC does not merely capture frequency of use, but reflects a set of competences closely aligned with the concept of ChatGPT literacy as described by Lee and Park [

53]. The UC scale encompasses understanding how the model operates, critical evaluation of the quality and reliability of its outputs, the design of effective prompts, and the use of ChatGPT for creative and analytical tasks, as well as reflection on ethical and legal issues. This positions the construct within the broader framework of AI literacy, which is commonly defined in the literature as a combination of knowledge about how models function, practical skills in using them, and critical reflection on their limitations [

93]. In light of reviews of experimental studies on the impact of ChatGPT on learning, which point on the one hand to improvements in performance, motivation, and higher order thinking, and on the other hand to risks of overreliance on the tool and erosion of cognitive autonomy [

44,

94,

95], the question of who possesses the competences necessary to harness the potential of GenAI without losing cognitive autonomy becomes particularly salient. The results of this study suggest that such competences are most strongly associated with high levels of digital skills and personal innovativeness, which may, in turn, contribute to further stratification within the population of adult learners.

The literature on adult education and lifelong learning emphasizes that generative AI can support the personalization of learning pathways, reduce time-related barriers, and intensify feedback processes [

52,

96]. At the same time, researchers caution that without the parallel development of critical digital competences and ethical reflexivity, such tools may reproduce or even exacerbate existing educational inequalities [

97,

98]. The present findings align with this paradigm, demonstrating that advanced use of ChatGPT in adult education is not evenly distributed but is strongly linked to individuals’ competence related resources and dispositions, and thus indirectly to their socio-economic position and prior educational trajectories.

6. Practical Implication for Education

The study demonstrates that the level of digital skills and personal innovativeness that determines whether a GenAI tool becomes a genuine support for learning or another domain in which digital inequalities are reproduced. This finding carries important practical implications for adult education. We argue that adult education programmes, including universities, postgraduate studies, vocational courses, and universities of the third age, should treat the development of digital skills as a goal equivalent to the development of subject specific competences. This concerns not only functional skills, but above all the critical component, such as understanding how language models operate, verifying the reliability of outputs, and recognizing bias as well as ethical and legal issues. AI literacy understood in this way is a prerequisite for ChatGPT to strengthen cognitive autonomy and reflexivity rather than encourage superficial content consumption.

Learning pathways should therefore be designed in a way that does not exacerbate the second and third levels of the digital divide. Educational institutions should embed compensatory DS modules before introducing advanced AI-based tasks, design learning activities that do not initially require high levels of hidden digital resources, for example, by including training in prompt design and critical evaluation of outputs as part of the course rather than as assumed entry competences, and systematically monitor which groups, defined by age, education, or place of residence, use GenAI in advanced ways and which remain limited to simple, reproductive applications.

We also recommend that educational interventions be targeted at groups at high risk of exclusion, in line with the logic of SDG 4.4. Given lower levels of digital skills among older cohorts and among some individuals with lower educational attainment, initiatives aimed at developing adults’ digital competences should be prioritized for these groups. In this context, a sustainable education policy entails the development of lifelong digital learning programs for adults outside large urban centers, linking GenAI training to concrete professional and civic goals such as employability, entrepreneurship, and social participation, and providing institutional support mechanisms, including tutoring, AI advisors, and digital competence libraries, for individuals who are unable to address existing skill gaps independently.

Personal innovativeness emerges as an independent predictor of advanced use of ChatGPT, meaning that individuals with higher levels of innovativeness are more likely to employ the tool for creative, analytical, and exploratory tasks. In educational practice, this implies the need to incorporate project based and experimental assignments involving ChatGPT, such as designing individual workflows, integrating the tool with other systems, or developing personalized ethical guidelines, as well as fostering exploratory attitudes and tolerance of uncertainty among adult learners. This can be achieved, for example, through open ended tasks that require iterative interaction with the model and through showcasing examples of GenAI use in the development of innovative solutions in areas central to sustainable development, including education, the labor market, health, and the environment.

The moderating role of gender indicates that the relationships linking digital skills and personal innovativeness to advanced use of ChatGPT may differ in strength between women and men. For this reason, adult education practices should focus on diagnosing psychological and social barriers faced by women, such as lower self-confidence in ICT despite objectively comparable competences, and on strengthening women’s digital agency through mentoring initiatives, role models, and project-based activities with tangible social impact.

From an academic perspective, we emphasize that in educational practice ChatGPT can function not only as a technical tool, but also as a space for engaging with content related to the Sustainable Development Goals, for example, through the analysis of scenarios for energy transition, social justice, or educational policy. Linking the development of digital skills and personal innovativeness with themes of sustainable development enhances coherence between learners’ goals, educational policy, and the 2030 Agenda, and supports the formation of digital capital oriented toward addressing societal challenges rather than solely toward individual efficiency.

7. Limitation and Future Research

7.1. Limitation

The sample comprises adult individuals who, at the time of the study, were actively upgrading their qualifications and simultaneously using ChatGPT. This limits the generalizability of the findings to the entire adult population in Poland. The use of an online CAWI survey also means that all key variables, namely digital skills, personal innovativeness, and use of ChatGPT, are based on self-reported data. This may introduce bias resulting from socially desirable responding and from respondents’ tendency to overestimate their own competences and level of advanced ChatGPT use. The absence of objective behavioral measures, such as activity logs or analyses of actual prompts and learning artifacts, constrains the ability to assess the real patterns of GenAI use with greater precision.

In addition, the data are cross-sectional in nature, which precludes causal inference in a strict sense. Although the SEM model suggests that digital skills and personal innovativeness act as predictors of use of ChatGPT, reciprocal relationships cannot be ruled out. For example, advanced use of ChatGPT may over time enhance certain components of digital skills or influence self-assessments of innovativeness. The lack of a temporal dimension also prevents observation of how stable patterns of GenAI use stratification are across the adult learning life course.

Another limitation stems from the fact that the proposed model focuses on two key individual resources, digital skills and personal innovativeness, and on a single tool, ChatGPT. It does not incorporate the broader institutional context, such as the policies of universities or training providers, assessment practices, or access to instructional support, nor does it include other psychosocial characteristics, for example, learning motivation or pro sustainability attitudes and values. This constrains the capacity to fully capture the mechanisms that lead to more sustainable or unsustainable patterns of GenAI use. Furthermore, this study focused on ChatGPT as the primary LLM, while other major language models (e.g., Claude, Gemini, Llama) are increasingly used in adult education; future research should investigate whether individuals with higher personal innovation prefer alternative LLMs or multi-model workflows over ChatGPT alone.

In addition to the above, it is worth mentioning that the constructs included in the model (DS, UC and PI) are measured based on respondents’ self-assessment. This raises the issue of the declarative nature of the data, which is the most common approach in research involving large samples.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the study concentrates on the social dimension of sustainable development, including issues of equal opportunity, the digital divide, and lifelong learning. It does not address the environmental consequences of the widespread adoption of GenAI, such as energy consumption and the carbon footprint of AI infrastructures, which are increasingly recognized as important components of sustainable digital education.

7.2. Future Research

An interesting direction for future research involves longitudinal studies tracking how digital skills, personal innovativeness, and patterns of GenAI use among adult learners evolve over time, both within individual educational programmes and across the broader lifelong learning trajectory. Such designs would allow for an assessment of the durability of the observed stratification and for the identification of critical moments at which educational interventions are most effective from the perspective of sustainable competence development.

Another promising avenue concerns studies examining the extent to which targeted programs aimed at developing digital skills, including critical digital competences and AI literacy, as well as personal innovativeness, lead to increases in advanced and reflective use of GenAI and to improved educational outcomes. Future research could also incorporate institutional policies and regulations governing the use of GenAI in educational settings, such as bans, transparency requirements, and ethical guidelines, as well as the availability of instructional support, including teacher training and AI competence centers. This would make it possible to better understand the conditions under which GenAI functions as a tool that reduces educational inequalities and those under which it reinforces them.

Given the specificity of the Polish adult education system and the level of digital competences, it is advisable to validate the proposed model in other countries and sectors, including corporate education, sector specific training, and reskilling programs. This would help determine whether the mechanisms of GenAI use stratification are universal or dependent on institutional context and public policy frameworks related to digitalization and sustainable development.

There is also a clear need for in-depth qualitative research, such as interviews, learning diaries, and case studies, to explore how adult learners and educators actually integrate GenAI into their practices, how they negotiate the boundary between support and delegation of the learning process to the model, and how they conceptualize responsibility, ethics, and sustainable technology use.

Finally, future studies should examine whether and how awareness of the environmental costs associated with GenAI solutions, including energy consumption and carbon footprint, influences attitudes toward their use in education, particularly among groups that strongly identify with sustainability values. Such research could inform the design of programs that integrate the development of digital skills and personal innovativeness with social and environmental responsibility, rather than treating these dimensions as independent of one another.

8. Conclusions

The conducted study allows several concluding remarks to be formulated. First, it empirically confirms that digital skills constitute a key predictor of advanced use of generative AI tools in adult education. Higher levels of DS are associated with more frequent and more complex use of ChatGPT, encompassing critical evaluation of outputs, creative content generation, data analysis, and ethical and legal reflection, and this effect remains robust even after accounting for personal innovativeness.

Second, personal innovativeness emerges as a significant and independent predictor of advanced ChatGPT use. The results indicate that a propensity to experiment with new technologies and openness to innovation not only facilitate the adoption of the tool itself, but are also linked to a greater readiness to exploit its potential in creative, reflective, and integrative ways, including its combination with other digital tools.

Moreover, the joint consideration of digital skills and personal innovativeness reveals a mechanism of GenAI use stratification. Individuals with high levels of both resources form a group of privileged users who are capable of leveraging ChatGPT as an advanced tool supporting lifelong learning, whereas those with lower levels of DS and/or PI are more likely to remain at the level of simple and superficial applications. This pattern aligns with the concepts of second and third level digital divides and with digital capital theory.

The analysis also identified the strength of the relationships between digital skills, personal innovativeness, and advanced use of ChatGPT may differ between women and men, with stronger associations observed among men. The observed differences may be related to gendered patterns of technological socialization, as well as to differences in self-assessed digital competences, which have been widely discussed in the literature. It is also possible that women and men differ in their preferred ways of using generative artificial intelligence tools. This finding suggests the need to incorporate a gender perspective in research on the use of GenAI in adult education, as well as in the design of interventions aimed at developing digital competences and AI literacy, in order to avoid reproducing the gender-based digital divide documented in OECD and Eurostat reports.

Finally, the results provide strong support for treating digital skills and personal innovativeness as key resources that condition whether generative AI becomes a tool for genuine cognitive and educational empowerment for adult learners or, alternatively, another factor that deepens existing inequalities in access to developmental opportunities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and M.J.; methodology, R.W., K.H.-B., A.S.-M. and G.S.; software, R.W.; validation, R.W. and M.J.; formal analysis, A.S.-M., A.S.-P. and G.S.; investigation, R.W., A.S.-M. and G.S.; resources, R.W.; data curation, A.S.-M. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W., K.H.-B., M.J., A.S.-M., A.S.-P. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, R.W., K.H.-B., M.J., A.S.-M., A.S.-P. and G.S.; visualization, R.W., A.S.-M., A.S.-P. and G.S.; supervision, R.W.; project administration, R.W.; funding acquisition, R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science under the “Regional Excellence Initiative” Program, grant number RID/SP/0034/2024/01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Participants of the University of Economics in Katowice (protocol code 2/2025, approval date: 26 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CAWI | Computer Assisted Web Interviewing |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| DS | digital skills |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| PI | Personal Innovativeness |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| UC | Use of ChatGPT |

| WLSMV | Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance adjusted |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measuring scales’ items.

Table A1.

Measuring scales’ items.

| Measuring Scales’ Items |

|---|

| Digital Skills (DS) |

I know how to find information on a website no matter how it is designed I know how to use advanced search functions in search engines I know how to check if the information I find online is true I can create a document with text, diagrams, tables, reports, and advanced formatting I can convert content from one format to another format I can search and find information in an object using appropriate keywords and advanced criteria and filters I can download content and save it directly to the relevant folder I can store and synchronize content on the Cloud I can save and keep on content in multiple storage devices I can evaluate whether some information is hoax, fake, scam, or fraud I can communicate with people and/or organizations using various synchronous and asynchronous. communication tools and smart devices I can collaborate with people using various smart devices, platforms and digital tools I can translate content into another language using translation tools

|

| Personal Innovativeness (PI) |

I enjoy experimenting with new digital technologies When I learn about a new digital technology, I try to use it as soon as possible Among my peers, I am usually the first to try out new digital technologies

|

| Use of ChatGPT (UC) |

I can train and fine-tune ChatGPT for specific purposes or applications I have the ability to identify and solve technical problems of ChatGPT I have the ability to use ChatGPT in conjunction with other tools or technologies I can compare and evaluate the functions of ChatGPT and other language models I can understand how ChatGPT generates responses I can understand how ChatGPT works I can evaluate the accuracy of ChatGPT responses I can determine whether ChatGPT’s response is true I can evaluate the reliability of ChatGPT’s responses I can identify errors in ChatGPT’s responses I can evaluate the completeness of ChatGPT’s responses I can recognize and explain bias in ChatGPT’s responses I can communicate effectively with ChatGPT I can ask appropriate and effective questions to ChatGPT I can use technical terms in conversations with ChatGPT I can ask accurate questions to ChatGPT using rich vocabulary I can elicit a response from ChatGPT to suit a particular situation I can use ChatGPT to generate new ideas or solutions I can do creative writing or storytelling using ChatGPT I can use ChatGPT to generate insights and trends on large datasets I can improve my creativity or innovation skills using ChatGPT I can identify potential ethical issues associated with the use of ChatGPT I can explore legal or ethical considerations related to the use of ChatGPT I can recognize potential privacy issues related to the use of ChatGPT I can use ChatGPT ethically

|

References

- Bond, M.; Khosravi, H.; De Laat, M.; Bergdahl, N.; Negrea, V.; Oxley, E.; Pham, P.; Chong, S.W.; Siemens, G. A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.S.; Baskar, T.; Siranchuk, N. Examining University Obsolescence Claims in the Conversational AI Era. Partn. Univers. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2025, 2, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Schmidt, S.W. Empowering Online Adult Educators: Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Enhanced Instructional Strategies. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2025, 2025, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M. Counterfeit judgments in large language models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2528527122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, L.; Mellor, J.; Rauh, M.; Griffin, C.; Uesato, J.; Huang, P.; Cheng, M.; Glaese, M.; Balle, B.; Kasirzadeh, A.; et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from large language models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.04359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, J. The Digital Divide; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2020; ISBN 9781509534456. [Google Scholar]

- van Deursen, A.J.; van Dijk, J.A. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, R.; Kol, J.; Stolecka-Makowska, A.; Szojda, G. Digital Consumer Behavior in Poland and Its Environmental Impact Within the Framework of Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, A.; van Deursen, A.; van Dijk, J. Determinants of Internet skills, use and outcomes. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 992–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Yao, J.E.; Yu, C. Personal innovativeness, social influences and adoption of wireless Internet services via mobile technology. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossmann, A. Digital maturity: Conceptualization and measurement model. In Proceedings of the Thirty Ninth International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Awdziej, M.; Jaciow, M.; Lipowski, M.; Tkaczyk, J.; Wolny, R. Students’ digital maturity and its implications for sustainable behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchenko, Y.; Gogua, M.; Golovacheva, K.; Smirnova, M.; Alkanova, O. A critical review of digital capability frameworks: A consumer perspective. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2020, 22, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perifanou, M.; Economides, A.A. An instrument for the digital competence actions framework. In ICERI2019 Proceedings; IATED: Seville, Spain, 2019; pp. 11139–11145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.J.; Schneider, L.S.; van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Laar, E. The Youth Digital Skills Indicator: Report on the Conceptualisation and Development of the ySKILLS Digital Skills Measure (ySKILLS Deliverable 3.1); KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Colombo, G.; Pezzetti, R.; Nicolescu, L. Consumer empowerment in the digital economy: Availing sustainable purchasing decisions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, Ł. Pomiar kompetencji cyfrowych—Dziesięć najczęstszych wyzwań metodologicznych. Probl. Opiekuńczo-Wychowawcze 2023, 620, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynon, R. Becoming digitally literate: Reinstating an educational lens to digital skills. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 47, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Awdziej, M.; Jaciow, M.; Lipowska, I.; Lipowski, M.; Szojda, G.; Tkaczyk, J.; Wolniak, R.; Wolny, R.; Grebski, W.W. Encouraging residents to save energy by using smart transportation: Incorporating the propensity to save energy into the UTAUT model. Energies 2024, 17, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]