1. Introduction

Sustainable Development, as defined in the Brundtland Commission Report (1987), refers to “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

1]. Although this definition recognizes both human beings and nature as central to development, several authors argue that the institutionalization of Sustainable Development has reinforced a productivist logic that prioritizes market efficiency and economic performance, often subordinating social equity and environmental protection [

2,

3,

4]. This productive and anthropocentric bias has raised persistent questions regarding the capacity of the Sustainable Development paradigm to ensure equity and environmental protection while sustaining economic growth.

In this context, alternative development models have emerged, particularly Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay), which is grounded in community coexistence, cultural values, and harmony with nature. Buen Vivir seeks to maintain balance among individuals, communities, productive activities, and the natural environment [

2]. It prioritizes collective well-being over individual accumulation [

3] and promotes community-based development aimed at achieving harmony between society and nature [

4]. In Ecuador, Sumak Kawsay is founded on principles of respect for nature, complementarity, and reciprocity [

5], as well as social equity, plenitude, and communal power [

6].

Buen Vivir proposes equilibrium across the social, environmental, and economic dimensions of sustainability, integrating diverse intellectual currents—including degrowth, deep ecology, and feminist economics—that question the compatibility of capitalism with harmonious human–nature relationships [

7]. Its cultural, social, and environmental meanings are reflected in the interrelated notions of Sacha Runa Yachay (harmony with oneself), Runakuna Kawsay (harmony with communities), and Sumak Allpa (harmony with nature) [

8]. This biocentric perspective also resonates with contemporary critical approaches such as the Homogenocene framework, recently conceptualized as a historically rooted process of biocultural devastation associated with colonial expansion and global homogenization, which highlights the need to reverse global biocultural homogenization [

9]. In this sense, Buen Vivir also shows conceptual proximity to ethical–ecosystemic proposals such as Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ encyclical and Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis, both of which conceive the planet as an interdependent living system [

10,

11].

From the perspective of knowledge generation, Buen Vivir represents an alternative epistemology in which knowledge emerges from community praxis, ancestral memory, and relational coexistence with living territories, rather than from purely extractive or technocratic scientific logics. This epistemic dimension contributes to the decolonization of sustainability debates by recognizing plural ways of knowing and producing knowledge.

Accordingly, this study addresses the following research question: What are the contributions of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) as a Latin American alternative to the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainability? While previous literature has examined Buen Vivir from philosophical, legal, or economic perspectives, limited empirical evidence systematizes how its contributions are simultaneously articulated across these three dimensions. This research addresses that gap through a systematic review of scientific publications, identifying the critical elements that characterize Buen Vivir as a paradigm capable of guiding sustainable community development from a Latin American perspective.

The following sections present the methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions of the study. The findings illustrate how the social dimension emphasizes culture, education, and political–legal processes; the economic dimension articulates solidarity and community-based economies through Indigenous entrepreneurship, feminist, local, and cooperative practices; and the environmental dimension highlights territorial governance and ecological management. The discussion and conclusions reflect on the need to integrate these three dimensions for sustainability to function as a holistic and harmonious process oriented toward community well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

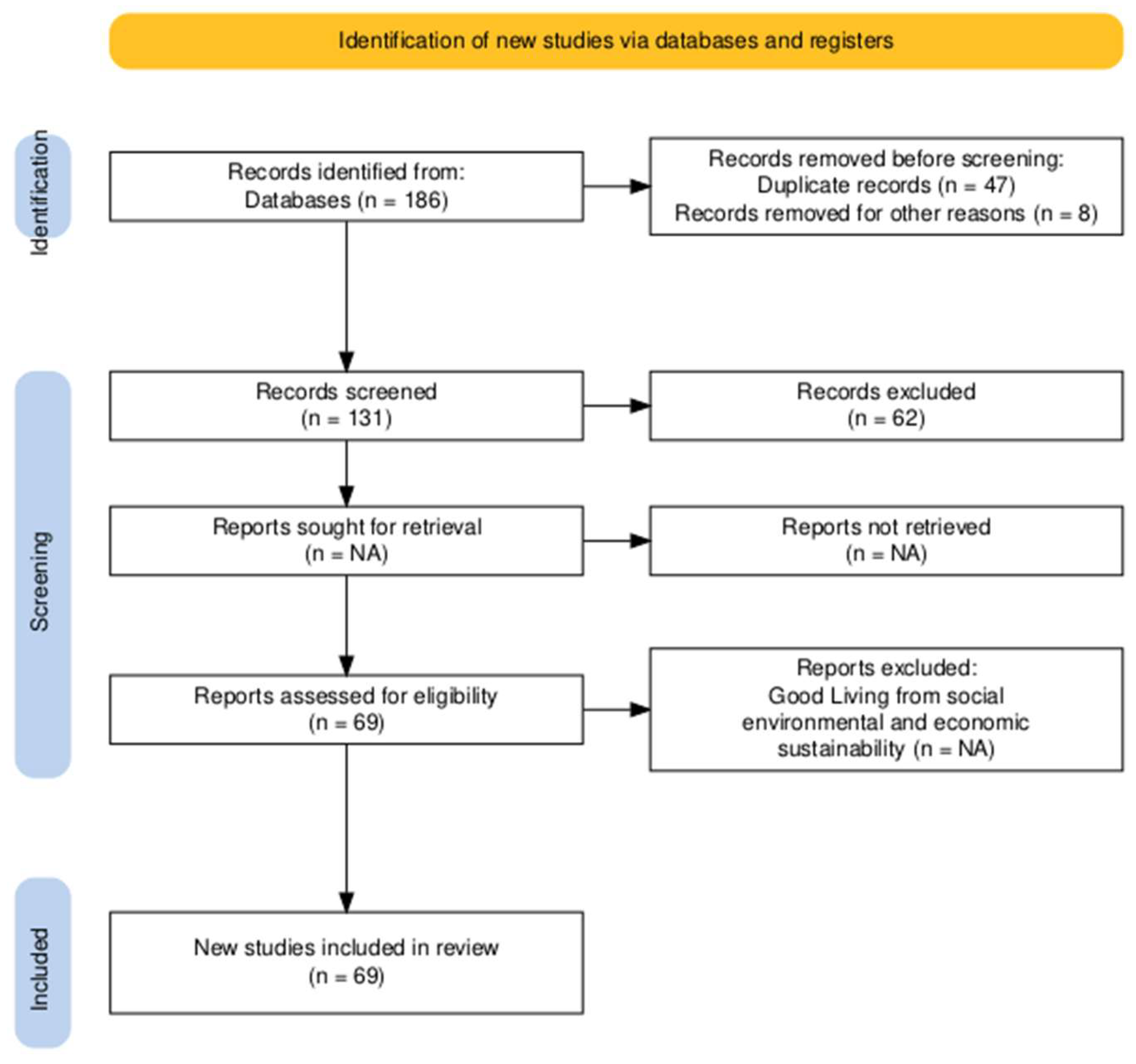

This study followed a qualitative methodological design, using documentary analysis as the primary technique and systematic content analysis of scientific publications as the main analytical tool. The research was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 Statement, which served as a guideline for the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews, ensuring transparency, comprehensiveness, and methodological rigor. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram was generated using the official online application available on the PRISMA website, and the corresponding PRISMA 2020 checklist was completed and included as

Supplementary Materials [

12]. The full process of identification, screening, and inclusion is presented in

Figure 1. In addition, the protocol for this systematic review was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) under the identifier

https://osf.io/4tm3k/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

The search strategy was implemented in the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases between 4 April and 15 April 2024. A Boolean search strategy was applied using the descriptors “Sumak Kawsay”, “Buen Vivir”, and “Good Living”, which are the terms most frequently used in the scientific literature to refer to the Latin American paradigm of Buen Vivir.

Based on the results presented in

Table 1, a total of 186 records were identified across both databases, with 94 records retrieved from Scopus and 92 from Web of Science. Publications were filtered to include only those published between 2018 and 2024, corresponding to the period in which Buen Vivir consolidated as a contemporary sustainability paradigm within academic scholarship. After merging the two databases, 47 duplicate records were removed, and 8 articles that did not address Buen Vivir or Sumak Kawsay were excluded. Subsequently, 131 full-text documents were assessed for eligibility, resulting in a final sample of 69 documents that met the inclusion criteria across the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability. The final selection process was guided by a critical and contextualized reading of the literature, aimed at identifying conceptual contributions, theoretical tensions, and interpretive insights related to Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) as a Latin American alternative to global sustainability. Artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used exclusively for linguistic and formatting purposes, including translation and grammar checking. All conceptual, methodological, analytical, and interpretive decisions were made entirely by the authors.

3. Results

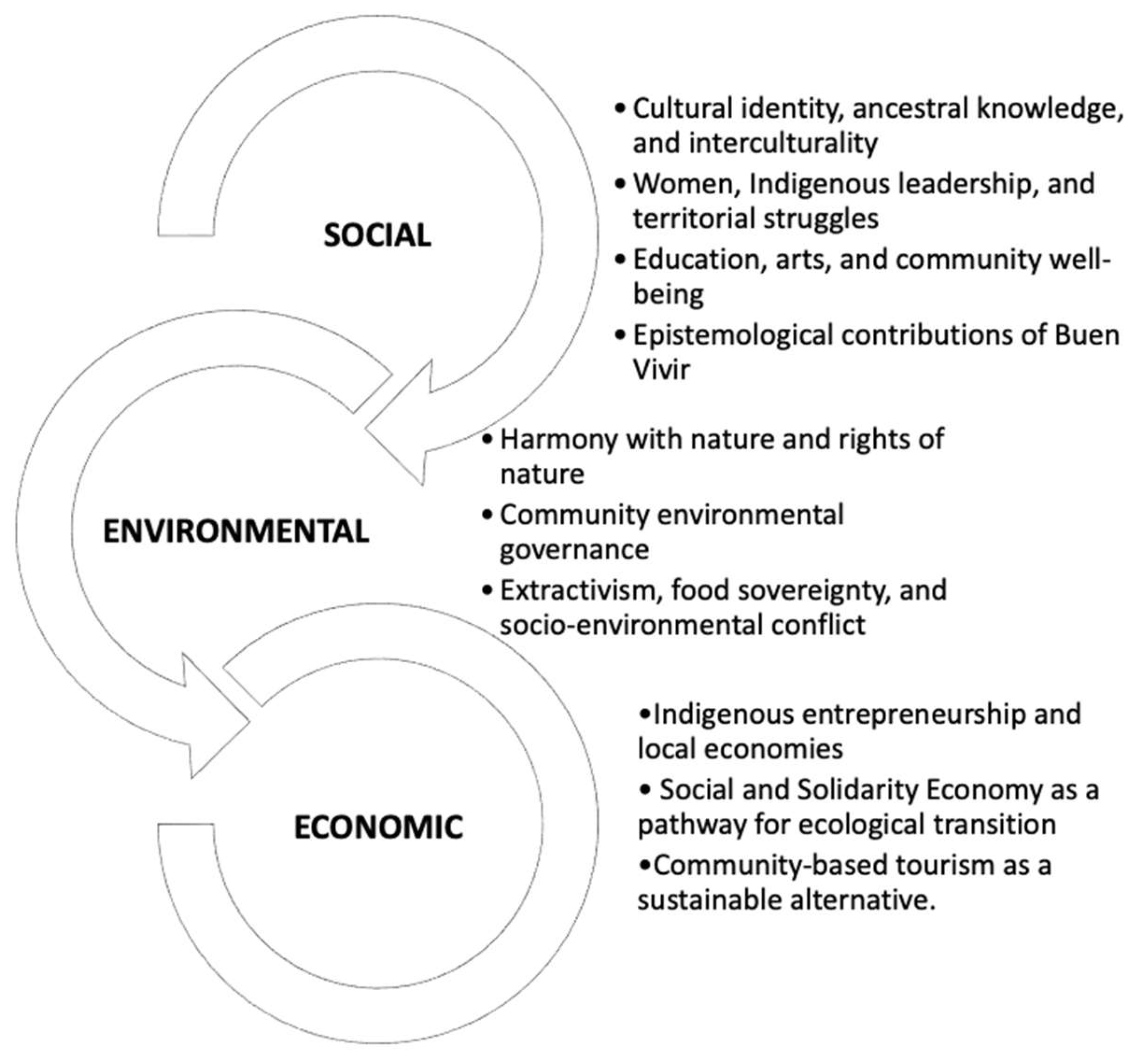

This section presents the critical contributions of

Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) as a Latin American alternative to global sustainability, analyzed through the social, economic, and environmental criteria derived from the documentary analysis (

Figure 2).

A total of 69 documents were analyzed, establishing relationships among the social, economic, and environmental criteria based on the contributions of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) as a Latin American alternative to global sustainability. These dimensions are not mutually exclusive; rather, they provide an analytical framework that facilitates a clearer understanding of the contributions of Buen Vivir to sustainability theory and practice.

3.1. Social Contributions of Buen Vivir

Most of the analyzed documents (n = 33) emphasize the centrality of community as the fundamental unit of well-being. The literature highlights cultural identity and autonomy, language, and the role of women, as well as education, inclusion, the arts, and the integration of ancestral and scientific knowledge as key mechanisms for fostering collective well-being. From this perspective, Buen Vivir challenges the Western assumption that individual prosperity can be achieved independently of community welfare.

3.1.1. Cultural Identity, Ancestral Knowledge, and Interculturality

The literature highlights the relevance of the social, cultural, political, and symbolic positioning of Indigenous youth in contemporary—particularly capitalist and neoliberal—societies, emphasizing persistent inequalities related to culture and language. In this context, Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) emerges as an alternative capable of reducing such inequalities [

14], especially in Latin America, where the integration of elements from Sustainable Development and Sumak Kawsay may contribute to the construction of more equitable and just social realities [

2]. Moreover, the incorporation of cultural and philosophical approaches that address well-being and happiness is essential for understanding Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) as a model applicable to contemporary Western contexts. In this regard, Aristotelian eudaimonia—associated with happiness, well-being, and human flourishing—constitutes a fundamental concept directly related to the essence of Sumak Kawsay [

15]. Through this integration of cultural perspectives, the epistemological and practical richness of subjective well-being is recognized, particularly in relation to sustainable human development, which should be incorporated into its assessment and measurement [

16].

At this point, it is important to highlight the contributions of José Carlos Mariátegui, who, from a historical and dialectical materialist perspective, established a critical engagement with Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay). Mariátegui challenged dominant notions of progress, culture, religion, history, and myth in Latin American societies by proposing the integration of Indigenous collectivism and Andean religiosity. Practices such as the minga—a millenary institution grounded in redistribution and reciprocity—illustrate the potential of these principles to inform political and economic structures [

17]. Despite the philosophical and practical relevance of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay), the literature also identifies significant challenges in consolidating it as a transformative paradigm in Latin America. In several cases, political actors have adopted Buen Vivir as a rhetorical device to capitalize on moments of social or economic tension. Consequently, it is essential to contextualize the concept and incorporate new perspectives that ensure its viability at both political and social levels [

7].

An essential aspect of this process is the recognition of community struggles to maintain autonomy and identity, thereby resisting cultural homogenization that threatens collective well-being [

8]. The understanding of Sumak Kawsay as a political, cultural, and decolonial project—rooted in the everyday lived experiences of Indigenous communities—aims to preserve their ways of life and promote collective welfare [

18]. Likewise, the dissemination of Indigenous languages and cultures contributes to valuing and respecting traditional knowledge systems within contemporary contexts [

19]. In this sense, Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities employ Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) to strengthen their resistance to extractivist capitalism, asserting that land is not merely a resource but an essential component of life [

20]. Their livelihoods are inherently linked to their territories, positioning Sumak Kawsay as a guiding framework for constructing more just and equitable societies through active community participation in environmental decision-making [

21].

3.1.2. Women, Indigenous Leadership, and Territorial Struggles

These dynamics are reflected in communal life practices—often described as practices of living well or living in happiness—based on collective labor, service, and natural principles. Such practices emphasize the interdependence between humanity and nature, encompassing cultural and spiritual dimensions that sustain both individual and collective well-being. These processes are often reinforced through public policies and community programs aimed at strengthening participatory planning [

22]. A crucial dimension of these social struggles is the participation of women in decision-making processes, given their central role in promoting social transformation through gender equality, leadership, and governance [

23]. Indigenous and rural women have led anti-mining and environmental movements, establishing epistemological dialogues with urban and mestizo feminist movements. These interactions contribute to the construction of a pluriverse of perspectives, enriching feminist thought in countries such as Peru [

24].

Women also play a fundamental role in education. Persistent inequalities continue to limit women’s access to educational opportunities, making it necessary to implement educational models that enable women to learn, share knowledge, and strengthen autonomy through both formal and non-formal education. Such models foster entrepreneurial and professional skills that contribute to family income and community well-being. These processes embody the principles of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) through participatory research approaches and the combined use of qualitative and quantitative methods, ensuring inclusion and cultural representation within local contexts [

25].

3.1.3. Education, Arts, and Community Well-Being

Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay), understood as a model of learning and social relations grounded in complementarity and reciprocity, promotes the transformation of education, ethics, and politics through epistemic diversity, fostering solidarity and justice within communities [

26]. Inclusive and equitable education informed by Buen Vivir seeks to transform pedagogical practices by integrating environmental and social justice, civic participation, and decolonial pedagogies [

27]. Education grounded in philosophical personalism further contributes by valuing human dignity and diversity through intercultural dialogue, thereby challenging reductionist or welfare-oriented approaches [

28]. Educational approaches inspired by Sumak Kawsay encourage the integration of community, cultural, and spiritual elements to reinforce respect for life, justice, and solidarity through the arts. These practices connect Latin American contexts with cultural identity [

29] while respecting Indigenous worldviews through education and intercultural dialogue [

30].

Intercultural education must therefore include the teaching of both foreign languages and ancestral languages in order to foster respect for local cultures, recognize diversity, and reduce cultural barriers that perpetuate discrimination against Indigenous communities [

31]. The National University of Education (UNAE) in Ecuador exemplifies this approach through intercultural bilingual education programs that recover ancestral knowledge and promote inclusion and equity. Guided by principles of unity, complementarity, communal power, and harmony with nature, these programs value linguistic and cultural diversity [

32]. Consequently, intercultural education that integrates ancestral and scientific knowledge emerges as an alternative capable of promoting regenerative development and ecological restoration [

33].

Education that fosters care and reciprocity between human and non-human beings—through eco-territorial and eco-media practices such as poetry and music—strengthens social and environmental justice [

34]. Artistic initiatives guided by Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) improve physical and mental health, strengthen social bonds through inclusion, and broaden understandings of well-being and development [

35]. In this sense, Sumak Kawsay contributes to the training of educators in the arts and humanities by enhancing both artistic and pedagogical competencies, grounded in philosophical and anthropological principles such as interculturality, decoloniality, transdisciplinarity, complexity, sustainability, equity, participation, and well-being [

36].

Within higher education, university extension projects have incorporated Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) as a framework for engaging with local communities. Through these initiatives, teaching and research practices are transformed by contextualizing academic processes and overcoming paternalistic models through solidarity and co-creation [

37]. Moreover, the implementation of Buen Vivir in schools and universities contributes to strengthening psychological and social support services for students, teachers, and staff, emphasizing holistic well-being [

38]. In psychology, Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) serves as a guiding framework for promoting mental health, self-determination, and emotional and social well-being by integrating ancestral knowledge into both individual and collective dimensions of community life [

39].

3.1.4. Epistemological Contributions of Buen Vivir

A central challenge for education from the perspective of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) is the digital divide, particularly in Latin America. Inclusive pedagogies that combine technical skills, ecological awareness, and cultural consciousness are essential for reducing this gap [

40]. At the intersection of Buen Vivir and information technologies, socioinformatics emphasizes the interdependence between nature and technology, highlighting their ethical and social implications. Technology should therefore be used responsibly and sustainably, in ways that respect social and planetary well-being. Education and public policy must promote collaboration among government, academia, and industry to foster sustainability-oriented technological development grounded in the principles of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) [

41]. At the same time, technology functions as a powerful communication tool for Indigenous communities, enabling them to share their struggles, human rights claims, and ancestral worldviews with broader audiences, thereby strengthening autonomy and collective agency [

42]. Environmental education inspired by Buen Vivir contributes to raising awareness of conservation and environmental care—particularly in relation to deforestation and its impacts—by engaging communities in educational processes that move beyond clearly defined legislation toward a deeper understanding of ecological stewardship [

43]. Overall, these findings highlight Buen Vivir as an epistemology grounded in relationality, in which knowledge emerges from coexistence, reciprocity, and community experience rather than from individual accumulation. Knowledge is generated through collective praxis, the intergenerational transmission of ancestral wisdom, and holistic interpretations of territory and life. These contributions demonstrate that Buen Vivir is not only a philosophical or political proposal but also a decolonial framework for knowledge production, in contrast to Western paradigms rooted in informational extractivism and the separation between subject and object.

3.2. Environmental Contributions of Buen Vivir

Another group of publications (n = 27) argues that sustainability cannot be achieved without harmony between human beings and nature. From this perspective, the ecological dimension of Buen Vivir encompasses the rights of nature, ecological reciprocity, and the protection of biodiversity and ecosystems as essential conditions for collective well-being. Nature is therefore understood not as a resource but as a living entity whose integrity sustains life.

3.2.1. Harmony with Nature and Rights of Nature

Buen Vivir proposes a development model in which respect for nature and community values is prioritized over economic growth. This perspective emphasizes the regulation and control of natural resources, food sovereignty, and the recognition of water as a fundamental human right [

44]. Consequently, guaranteeing free access to water—particularly for low-income families and Indigenous communities—is essential to ensure the minimum vital resource required for a healthy and dignified life [

45].

Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) further emphasizes the recognition of nature as a subject of rights, promoting an equitable model of human development that seeks to reduce poverty without degrading ecosystems. This approach critically challenges the commodification of social and natural life characteristic of the economistic and productivist logic of Western modernity. Accordingly, Sumak Kawsay emerges as an alternative grounded in Indigenous worldviews that promote harmony between humanity and nature while reducing environmental exploitation [

46]. Within this framework, the recognition of nature as a subject of rights [

47,

48], together with the application of corrective mechanisms through environmental criminal law, highlights the need to educate and sensitize judges, prosecutors, and other judicial actors—as well as the broader public—regarding environmental protection. In addition, the promotion of international cooperation and partnerships for the exchange of resources and knowledge is considered essential for strengthening global environmental protection efforts [

49].

3.2.2. Community Environmental Governance

Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) also functions as a reference framework for environmental and territorial governance, fostering an integrated approach that promotes environmental responsibility through both community-based and institutional participation. Although education plays a central role in this process, it must be complemented by adequate infrastructure and effective state oversight to ensure biodiversity protection, ecological restoration, and conservation [

50]. Traditional and ancestral knowledge further contributes to the sustainable management of nature by promoting preservation practices and harmonious relationships between communities and their environments. This approach emphasizes the active participation of local populations in the planning and implementation of policies and projects affecting their territories [

51].

The incorporation of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) into the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia institutionalizes principles of social justice, equity, and sustainability [

52]. Indigenous justice and its influence on political and social structures in these countries seek to reduce inequalities between metropolitan and historically colonized populations, fostering plurinational states and intercultural justice [

53]. Alongside these processes, legal pluralism and decolonial perspectives have enabled the integration of diverse and holistic visions into constitutional frameworks [

54].

The influence of Sumak Kawsay on public policies, development plans, and constitutional, academic, and scientific discourses is well documented [

55], particularly in relation to plurinationality, multiethnicity, and the rights of nature [

5]. Political–environmental debates play a decisive role in addressing environmental conflicts, as intercultural and plurinational perspectives complicate understandings of resource extraction—especially in contexts marked by poverty and extractivism [

56].

An illustrative example of its applicability can be found in Colombia’s transitional justice process, where Sumak Kawsay has been proposed as a framework for promoting inclusion and equity in reconciliation efforts by prioritizing the participation of local communities and their specific territorial needs [

57]. Moreover, the historically constructed dichotomy between nature and society characteristic of Western thought can be overcome through Sumak Kawsay, which draws on ancestral principles of complexity, interculturality, community, and transdisciplinarity to inform inclusive research and practice. This approach contributes to ecological economics by integrating Indigenous worldviews into sustainability-oriented frameworks [

58]. From a cultural perspective, Buen Vivir—linked to territorial planning—offers a holistic vision that fosters creative and sustainable economic practices rooted in identity and social cohesion, thereby enhancing local well-being [

59].

3.2.3. Extractivism, Food Sovereignty, and Socio-Environmental Conflict

From the perspective of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay), multiple intellectual currents—including socialist, post-structuralist, indigenist, and neo-developmentalist approaches—shape public policy debates and the construction of alternative development paradigms [

60]. A central concern within this context is extractivism and the policies that sustain it, which disproportionately affect Indigenous peoples and rural communities. It is therefore essential not only to recognize their needs but also to integrate their perspectives into policymaking processes in order to ensure inclusive and genuinely beneficial outcomes [

61]. The meaningful inclusion of Indigenous peoples—particularly in addressing poverty and inequality—has the potential to improve access to healthcare and overall quality of life through the recognition of collective rights, traditions, and territorial identities [

62]. In contrast, institutional structures often reproduce exclusion through colonial legacies. Buen Vivir thus emerges as an alternative framework that directly addresses inequalities related to territory, gender, and ethnicity, contributing to decolonial and intercultural approaches to sustainability [

63].

Peasant and Indigenous movements play a crucial role in expanding democratic spaces and acting as political agents guided by the values of Sumak Kawsay [

64]. The right to self-determination, especially for Indigenous communities, becomes a key instrument in struggles for human rights and social emancipation [

65]. The constitutional recognition of Sumak Kawsay in Ecuador and Bolivia enables Indigenous communities to define their own visions of society, nationhood, and collective well-being through territorial defense [

66]. This constitutional shift signals a broader reconfiguration of sovereignty. Rather than adhering to post-Westphalian, state-centered models, sovereignty is articulated through localized and community-based practices that reclaim control over territory, food systems, and ways of life. This perspective aligns with food sovereignty scholarship, which conceptualizes sovereignty as emerging from grassroots struggles against neoliberal governance and global homogenization, emphasizing collective autonomy, solidarity-based economies, and sustainable territorial practices [

67].

Legal and political challenges related to food sovereignty further require the development of policies that integrate sustainable food production and equitable distribution systems [

68]. In this regard, Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) operates simultaneously as a critique of conventional development models and as a viable alternative grounded in social justice and sustainability [

4]. It advances a holistic understanding of development that integrates cultural, environmental, social, and economic dimensions, incorporating ancestral visions of collective well-being in which food sovereignty occupies a central place [

69].

3.3. Economic Contributions of Buen Vivir

A third group of publications (n = 9) addresses alternative economic models. These studies emphasize solidarity economies, local markets, food sovereignty, non-extractivist development pathways, and limits to economic growth as core principles. Buen Vivir does not reject economic activity; rather, it reframes it as a means to strengthen collective well-being instead of individual accumulation.

3.3.1. Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Local Economies

Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) highlights the relevance of community-based, solidarity-oriented, and agroecological economies, as well as rural cooperatives, peasant networks [

70], and Indigenous entrepreneurship. These initiatives strengthen community participation, reinforce food sovereignty, and contribute to poverty reduction. They emphasize the sustainability of Indigenous productive projects and the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in the formulation of public policies that support entrepreneurship grounded in reciprocity, community, and harmony with nature—constituting a clear alternative to conventional economic development models [

71].

3.3.2. Social and Solidarity Economy as a Pathway for Ecological Transition

The solidarity economy constitutes a key instrument for local development, particularly by prioritizing collective work, reinforcing the role of women, and promoting progress that is not solely economic but also social [

72]. Social and solidarity economies foster cooperation and economic reciprocity, strengthening community self-determination and sovereignty while revaluing Indigenous cultures and knowledge systems [

73]. From this perspective, Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) can be operationalized as an alternative to capitalism through processes of decommodification, regulation, resizing, and redistribution of economic activities aimed at social justice, equity, and sustainability. These processes support local economies [

74] and small-scale family farming based on ecological practices that preserve soil and water quality while advancing food sovereignty. Such sovereignty is increasingly threatened by extractivist policies that generate displacement, restrict access to land and resources, and promote the use of agrotoxins that contaminate water and soil [

75].

Overall, the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) not only upholds the ethical principles of Buen Vivir but also strengthens community well-being and facilitates ecological transition by reducing dependence on extractivism. Cooperative production models, community markets, and agroecological initiatives demonstrate that environmental sustainability and economic autonomy can operate synergistically rather than in opposition.

3.3.3. Community-Based Tourism as a Sustainable Alternative

Community-based tourism represents a concrete expression of these dynamics and has significant potential to contribute to sustainable development at the local level. When integrated within the framework of Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay), tourism adopts a degrowth-oriented approach that prioritizes environmental protection, cultural revitalization, and community well-being over profit maximization [

76]. Community tourism also generates employment opportunities for local populations, strengthening local economies while preserving environmental and cultural values [

77].

Buen Vivir thus emerges as a comprehensive alternative to capitalism through its articulation with degrowth, solidarity, social, local, and feminist economies, influencing both public policy and academic production—particularly in Latin America [

3].

The complementarity of the social, environmental, and economic dimensions demonstrates that Buen Vivir does not operate in isolated sectors but rather constitutes a holistic paradigm rooted in community life, environmental responsibility, and solidarity-based economies.

The distribution of findings across sustainability dimensions is summarized in

Table 2. Of the 69 analyzed publications, 33 (48%) primarily address the social dimension, 27 (39%) the environmental dimension, and 9 (13%) the economic dimension. Although most studies focus on a single dimension, 19 publications (27%) explicitly examine intersections between two or more dimensions.

4. Discussion

The findings of this systematic review show that Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) emerges as a Latin American alternative that challenges the dominant global sustainability model. Although international sustainability frameworks call for balance among social, environmental, and economic criteria, this equilibrium often breaks down in practice and tends to shift toward productivism. Across the 69 documents analyzed, Buen Vivir integrates principles such as reciprocity, harmony with nature, cultural identity, and community life within a holistic perspective. A particularly strong contribution is observed in the social dimension, where collective well-being and culture are identified as foundational for sustainable territorial development [

14,

16,

32]. These elements are further reinforced through their epistemological significance, rooted in community autonomy, ancestral knowledge, and the political and symbolic positioning of Indigenous communities [

19,

23].

Importantly, Buen Vivir does not merely add cultural or community considerations to sustainability; it calls into question the epistemological foundations of sustainability itself. The reviewed publications suggest that knowledge is generated through intergenerational transmission, coexistence, and collective practices rather than through individual accumulation [

36]. This relational epistemology challenges Western perspectives grounded in the separation between subject and object and the extraction of information. Such a divergence has direct implications for education, requiring pedagogical transformation through curriculum design and teacher training rooted in solidarity, environmental ethics, and interculturality, with the aim of strengthening collective well-being [

24,

29]. The review also shows that artistic, psychological, and mental health approaches inspired by Buen Vivir can reinforce well-being through forms of community life that extend beyond material conditions and incorporate spiritual, affective, and cultural dimensions [

75]. This ontological shift has been described as a move toward relational and commons-based understandings of sustainability within current debates on Buen Vivir [

78].

The environmental dimension aligns with the biocentric orientation of Buen Vivir. Nature is not framed as a resource but as a living being whose integrity sustains life, consistent with ethical and legal principles that recognize nature as a subject of rights [

46,

47]. This orientation is not limited to declarative commitments; it is reflected in concrete priorities such as water sovereignty, biodiversity conservation, and environmental responsibility as necessary conditions for well-being [

49,

53]. However, these principles remain fragile in extractivist national contexts. In countries such as Ecuador and Bolivia, where Buen Vivir has been incorporated into constitutional frameworks, political tensions continue to emerge when plurinationality and the rights of nature coexist with the expansion of extractive industries [

50,

51]. These contradictions suggest that the transformative potential of Buen Vivir cannot rely solely on ethical principles; it also requires sustained institutional and state commitment to ensure the effective protection of community and territorial rights.

Despite these tensions, Buen Vivir enables forms of environmental governance grounded in territories through the integration of ancestral and scientific knowledge and by prioritizing community participation in decision-making [

61,

75]. Community practices related to conservation and intercultural justice appear as mechanisms that combine environmental care with social equity [

47,

61]. Furthermore, the review highlights that socio-environmental conflicts associated with extractive projects, agribusiness, and land dispossession must be addressed by recognizing the role of Indigenous, peasant, and local communities. Their territorial struggles for the defense of nature contribute significantly to democratization and sustainability [

49,

50].

In the economic dimension, Buen Vivir reframes the economy as a means to advance community well-being rather than as an end in itself. Agroecological, solidarity-based, and cooperative economies emerge as viable alternatives to capitalism grounded in autonomy, redistribution, and reciprocity [

3,

74]. The findings also suggest that degrowth and sustainability can reinforce one another, strengthening economic practices rooted in ecological responsibility and territorial identity [

72]. Likewise, peasant and Indigenous entrepreneurship is presented as a pathway to poverty reduction while fostering economic autonomy and food sovereignty—understood as the right of peoples to define their own food and agricultural systems in culturally appropriate and sustainable ways [

76,

79]. Community-based tourism represents another relevant example of an economic practice aligned with Buen Vivir, capable of generating employment and strengthening local economies while preserving environmental and cultural values [

76,

77].

Taken together, the three dimensions confirm that the theoretical and practical contributions of Buen Vivir operate in interdependent rather than isolated ways. Community life, ecological reciprocity, and solidarity-based economies mutually reinforce one another and shape a coherent sustainability paradigm. Nonetheless, the reviewed studies also reveal limitations. While the social and environmental dimensions show strong theoretical development, the economic dimension remains less explored and requires further empirical documentation. In addition, most publications focus on the Andean region; therefore, future research could examine the applicability of these principles across diverse sociocultural settings. Finally, although conceptual advances are evident, studies analyzing policy implementation or long-term community outcomes remain limited.

Overall, this systematic review highlights that Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) makes a significant contribution to global sustainability by foregrounding epistemological, ethical, and territorial foundations that have historically been overlooked in international agendas. Buen Vivir calls for a profound transformation in how sustainability is conceptualized and practiced, placing community life, territorial autonomy, and ecological responsibility at the core of development. In this sense, sustainability is not merely a technical challenge but a civilizational decision.

From a broader perspective, the contributions of Buen Vivir can also be situated within ongoing debates on eco-social transitions in the Andean region. These debates emphasize the need to move beyond growth-centered development models toward alternatives grounded in social justice, ecological integrity, and collective well-being. In this context, Buen Vivir aligns with and enriches discussions on post-extractivist transitions, community-based territorial governance, and relational approaches to human–nature interactions across Andean countries [

80,

81].

The reviewed literature suggests that Buen Vivir does not function as an isolated normative proposal but as part of a constellation of Andean and Latin American alternatives that challenge dominant development paradigms. Its emphasis on reciprocity, communal life, cultural identity, and the recognition of nature as a subject of rights resonates with broader eco-social transition frameworks that seek to integrate environmental sustainability with social inclusion and political transformation. By articulating sustainability as a relational and culturally embedded process, Buen Vivir contributes to a richer understanding of eco-social transitions grounded in territorial realities and epistemologies of the Global South.

From a broader decolonial perspective, the principles underlying Buen Vivir resonate with other Indigenous and relational worldviews beyond Latin America. African philosophies such as Ubuntu, for instance, emphasize interconnectedness, reciprocity, and collective responsibility as ethical foundations for social organization and ecological balance. Recent scholarship highlights how Ubuntu can offer a transformative framework for addressing contemporary crises, including climate change, by foregrounding solidarity, harmony, and relationality as core principles for sustainable development [

82]. This comparative perspective reinforces the argument that Buen Vivir is not an isolated normative proposal but part of a wider constellation of Indigenous epistemologies that challenge Western individualism, extractivist development models, and homogenizing global paradigms. By situating Sumak Kawsay alongside kindred philosophies such as Ubuntu, the discussion underscores the global relevance of relational ontologies rooted in Indigenous knowledge systems.

In this context, Buen Vivir can be understood as fostering exemplary ethical communities—collective forms of social organization grounded in reciprocity, care, and ecological responsibility—that offer concrete alternatives to dominant development paradigms. At the same time, these community-based practices give rise to forms of survival cosmopolitanism, through which local actors build translocal connections not based on cultural homogenization but on shared struggles for dignity, resilience, and ecological continuity. Together, these notions highlight how Buen Vivir operates across scales, anchoring ethical sustainability in territorial practice while enabling solidarities that transcend national and cultural boundaries.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review, based on the analysis of 69 selected documents, demonstrates that Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay) constitutes a multidimensional paradigm that enables a rethinking of global sustainability debates. While conventional approaches to sustainability emphasize, in theory, a balance among social, environmental, and economic dimensions, in practice they tend to gravitate toward productivism. In contrast, Buen Vivir advances a holistic orientation grounded in community life, cultural identity, reciprocity, and respectful coexistence with nature, underscoring the interdependence of these dimensions. Its contribution lies in the integration of ethical, epistemological, and territorial principles that make it possible to reconceptualize the relationship between human societies and nature from a relational perspective.

From this standpoint, Buen Vivir can be understood as a civilizational proposal for sustainability, centered on territory, communities, and the flourishing of life, rather than on purely technical or instrumental approaches. The synthesis presented in this review contributes to organizing a broad and fragmented body of literature, offering insights that strengthen theoretical debates and can inform decision-making in public policy and community-based practices.

At the same time, this review identifies important gaps in the existing body of research. The economic dimension remains less developed than its social and environmental dimensions, indicating the need for further theoretical refinement and empirical investigation. In addition, the predominance of studies focused on Andean contexts highlights the importance of conducting comparative research across diverse sociocultural settings. Although conceptual advances are evident, empirical evidence regarding institutional implementation, long-term community outcomes, and the sustained impacts of public policies remains limited.

In light of these findings, strengthening empirical research is essential to consolidating Buen Vivir as both a theoretical and practical framework for sustainability. Future studies could examine and compare experiences of implementation across different institutional arrangements and community contexts, as well as assess long-term social, environmental, and economic outcomes. Advancing these lines of inquiry will contribute to positioning Buen Vivir as a robust and relevant reference within global sustainability agendas.