Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Drivers of Shipping Service Industry Agglomeration and Port–City Synergy: Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Methods

2.1. Study Area

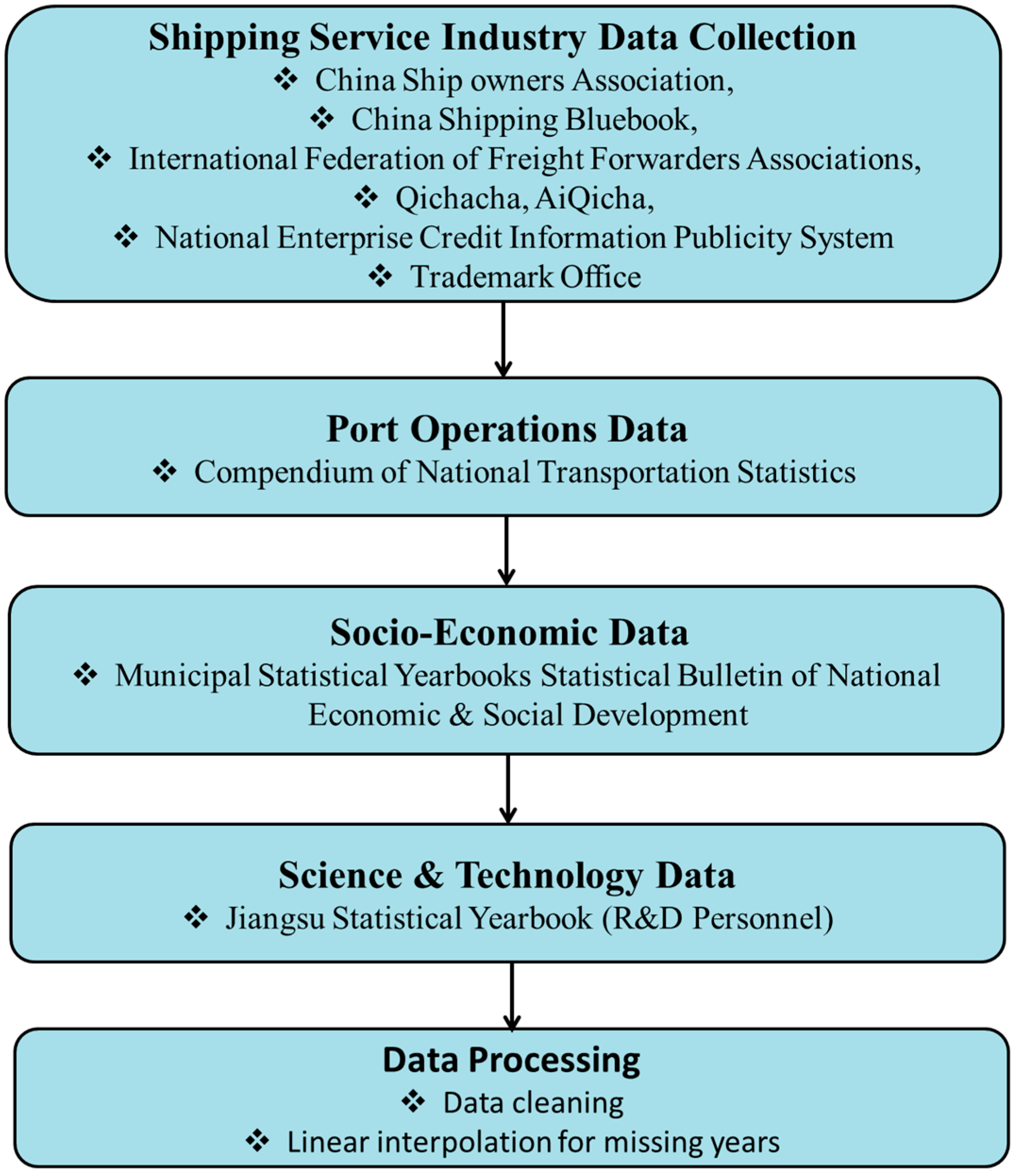

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Construction of the Evaluation Index System

2.3.1. Evaluation Index System for Port Operations and Urban Economic Development

2.3.2. Evaluation Index System for the Agglomeration Level of the Shipping Service Industry

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Entropy Method

2.4.2. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

2.4.3. Relative Development Model

2.4.4. Panel Tobit Model

3. Empirical Analysis

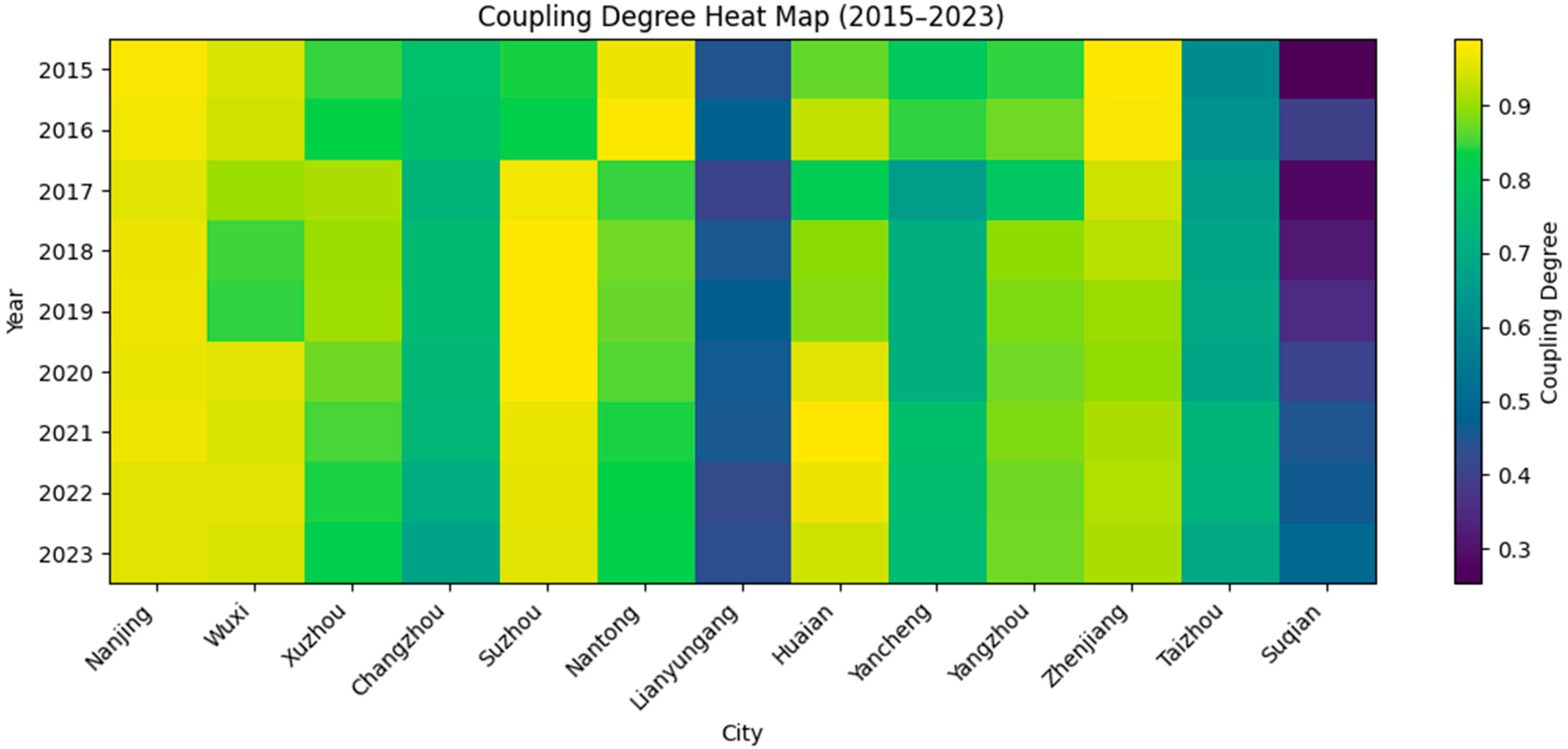

3.1. Coupling Degree Analysis

3.2. Analysis of Coupling Coordination Development

3.2.1. Temporal Evolution of Coupling Coordination Degree

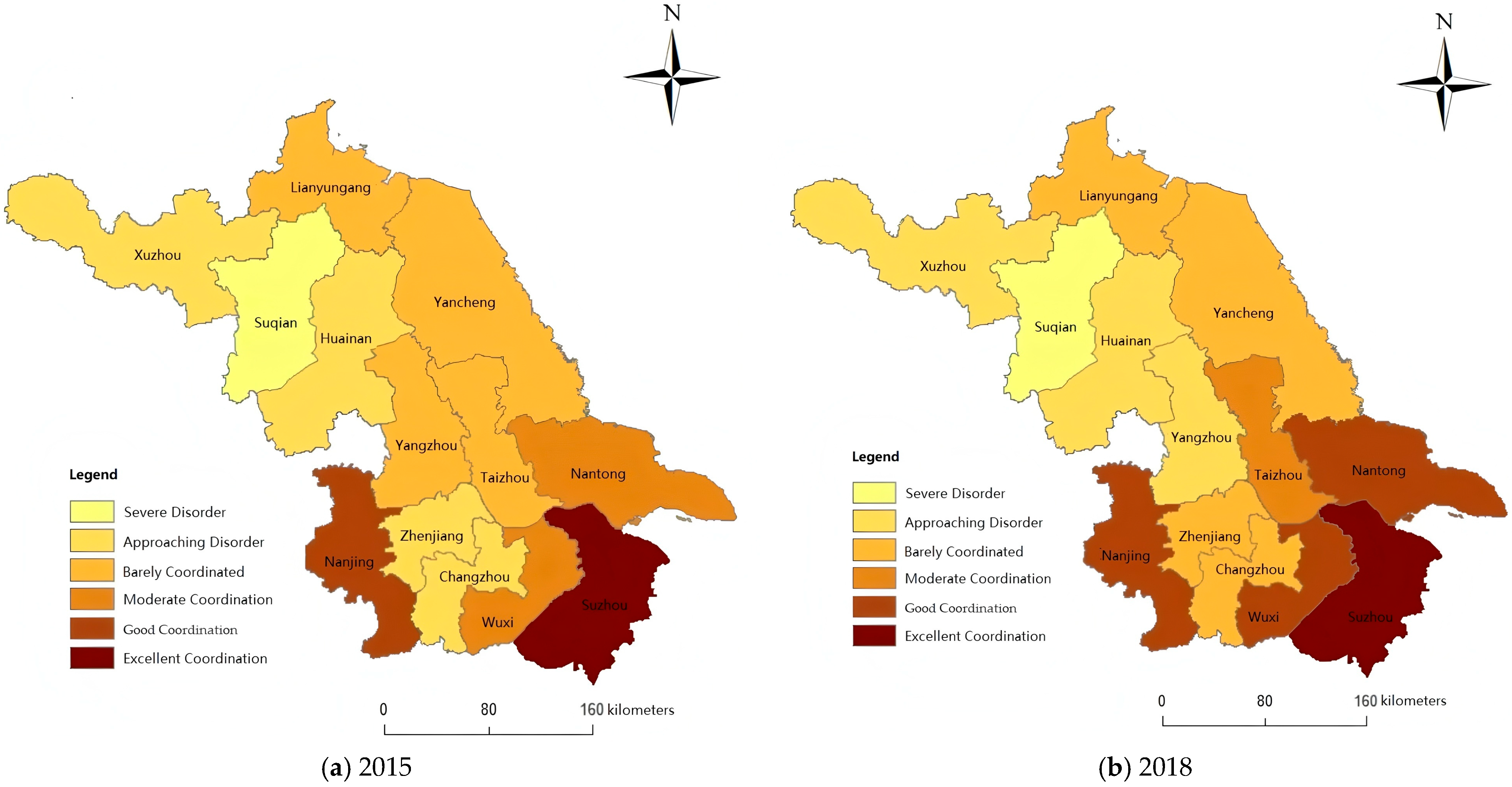

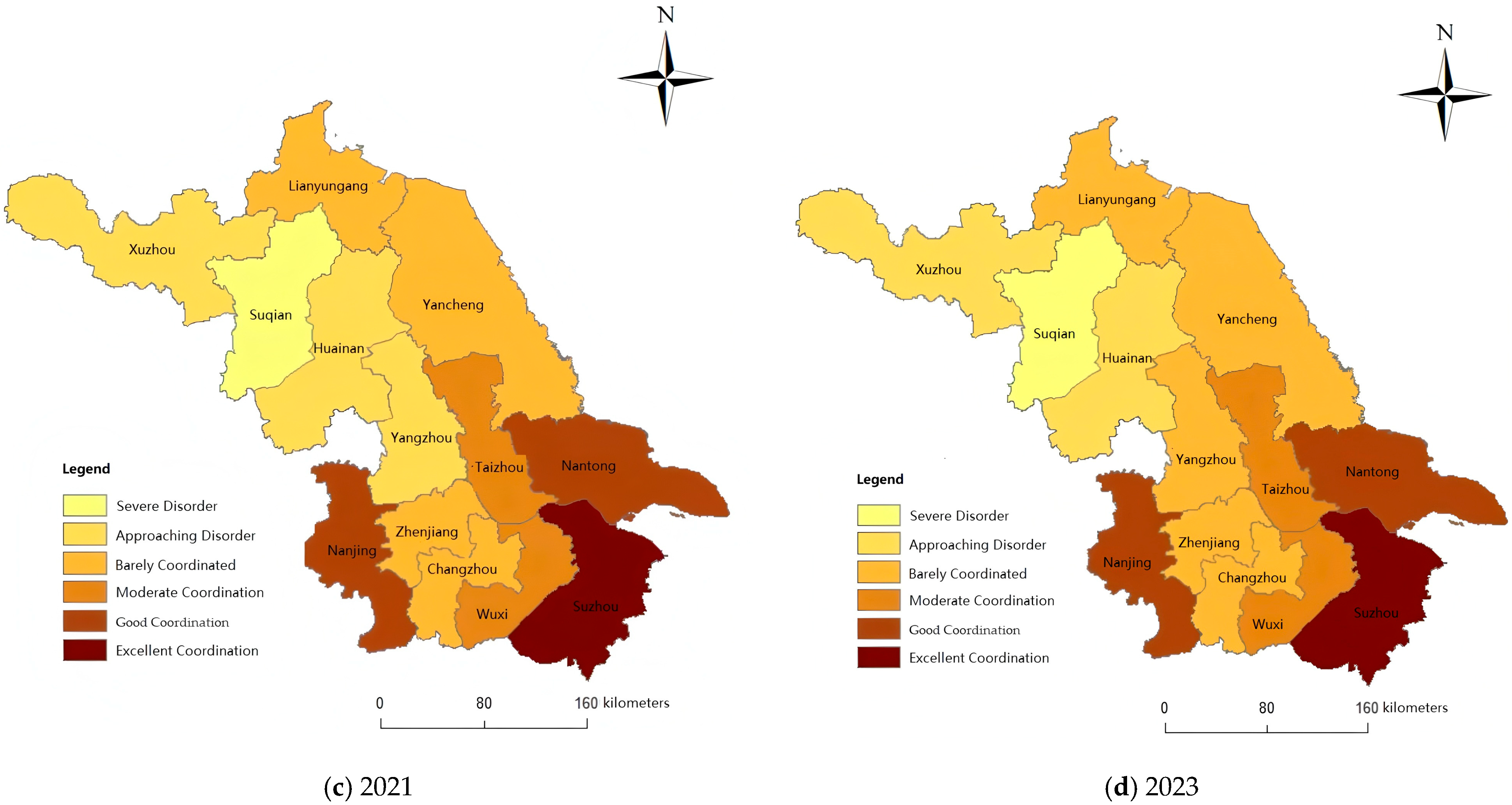

3.2.2. Spatial Evolution of the Coupling Coordination Degree

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Relative Development

3.3. Analysis of Driving Factors

3.3.1. Regression Results Analysis

3.3.2. Robustness Test

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Q.; Jia, P.; She, X.; Haralambides, H.; Kuang, H. Port integration and regional economic development: Lessons from China. Transp. Policy 2021, 110, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, E. Pursue the coordinated development of port–city economic construction and ecological environment: A case of the eight major ports in China. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 242, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, R. Analysis of environmental performance and interactivity of ports and regions. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.S.; Chen, X.; Du, L.N. Integration and coordinated relationship between port logistics and urban industrial economy in inland river port cities. Navig. China 2024, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W. Synergistic development of port–city complex systems: Empirical study of the Chengdu–Chongqing region. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 38, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Ye, J.; Gong, J. Evolution of competition pattern of inland container ports along the Yangtze River in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 109, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lan, Y.; Li, H.; Jing, X.; Lu, S.; Deng, K. Spatial-temporal differentiation and prediction of the coupling coordination degree between port environmental efficiency and urban economy. Land 2024, 13, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Beaverstock, J.V. Subcontracting the accountant! Professional labour markets, migration, and organisational networks in the global accountancy industry. Environ. Plan. A 1996, 28, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Derudder, B.; Faulconbridge, J.; Hoyler, M.; Ni, P. Advanced producer service firms as strategic networks, global cities as strategic places. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 90, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, P.; Zhang, N. Spatial pattern and influencing factors of the shipping service industry. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 913–929. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, N.; Lin, Y. Spatial evolution and influencing factors of the global advanced maritime service industry. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 708–724. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.H.; Su, H.; Zheng, Y.B. Spatial evolution of maritime producer services and high-quality integration of ports in the Yangtze River Delta. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2022, 31, 725–737. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Jiao, H.; Guan, J. Spatial distribution and functional evolution of shipping service industry in Shanghai. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2021, 41, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Tang, Q.R. Economic contribution of modern shipping service industry: Evidence from Guangzhou. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2014, 19, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Li, Q. High-end shipping service cluster in Tianjin based on symbiosis theory. J. Shanghai Marit. Univ. 2014, 35, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.H.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Jiang, J.L. Dynamic mechanism of the Yangtze River shipping service industry agglomeration based on Bayesian ridge regression. Navig. China 2024, 47, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Notteboom, T. Adaptive capacity of container ports in the era of mega vessels: Case of Antwerp and Hamburg. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 54, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Chen, S.; Gao, M.; Liu, H. Spatial heterogeneity and coupling coordination of cultural ecosystem service supply and demand: Case of Taiyuan City, China. Land 2025, 14, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.V.; Jacobs, W. Why are maritime ports (still) urban, and why should policymakers care? Marit. Policy Manag. 2012, 39, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Y. Upgrading port-originated maritime clusters: Insights from Shanghai. Transp. Policy 2020, 87, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook 2023; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Wan, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhou, W.; Liu, M. Evaluation of the coupling synergy degree of inland ports and industries along the Yangtze River. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Woo, S.H.; Li, K.X. Port–city synergism and regional development policy: Evidence from the Yangtze River Region. Transp. Res. Part E 2024, 192, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Jiang, S.; Gu, J.; Zhang, J. Coupling coordination and spatial correlation between logistics and the regional economy in the Yangtze River Delta. Sustainability 2023, 15, 992. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Qin, Y. Coupling characteristics of coastal ports and urban network systems based on flow space theory: Evidence from China. Habitat Int. 2022, 126, 102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.L.; Liu, S. Coordinated development evaluation and influencing factors of the digital economy and new energy battery industry agglomeration: The Pan-Pearl River Delta Region. J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 49, 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Ma, M.; Wen, W.; Qu, L. Relationship between the synergy degree of port–city systems and urban economic growth. China Soft Sci. 2015, 9, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Lei, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Ye, S. Spatiotemporal evolution and location factors of port and shipping service enterprises in the Yangtze River Delta. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, Y.; Liao, D.; Chang, V. Service function chain orchestration across multiple domains: A full mesh aggregation approach. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2018, 15, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, K.; Wang, Z.; Xu, A. Evolution of China’s wind power innovation network from the perspective of multidimensional proximity. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Xie, Z. Concentration in cross-border research collaborations and MNCs’ knowledge creation in host countries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Lü, J.; Liu, K.; Zhu, A.; Snoussi, H.; Zhang, B. Synchronous spatiotemporal graph transformer: A new framework for traffic data prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 10589–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Xu, Z.; Wei, M.; Wang, X. Strategic behavior of players in air–rail intermodal transportation: An evolutionary game approach. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2025, 126, 102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Category Level | Indicator Level | Indicator Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Port Operations | Infrastructure | Length of operational berths (m) | + |

| Number of berths | + | ||

| Number of 10,000-ton-class berths | + | ||

| Transport Services | Cargo throughput (10,000 tons) | + | |

| Foreign trade cargo throughput (10,000 tons) | + | ||

| Container throughput (10,000 TEUs) | + | ||

| Foreign trade container throughput (10,000 TEUs) | + | ||

| Urban Economy | Economic Scale | GDP (100 million yuan) | + |

| GDP per capita (yuan) | + | ||

| Total fixed asset investment (100 million yuan) | + | ||

| Industrial Structure | Industrial added value (100 million yuan) | + | |

| Balance of deposits in financial institutions (100 million yuan) | + | ||

| Domestic and Foreign Trade | Total retail sales of consumer goods (100 million yuan) | + | |

| Total value of foreign trade (100 million USD) | + |

| Coupling Degree | Coupling Stage |

|---|---|

| Disordered | |

| Low-level Coupling | |

| Antagonistic | |

| Transitional (Adjustment) | |

| High-level Coupling | |

| Ordered |

| Coupling Coordination Degree | Coordination Type |

|---|---|

| Severe Disorder | |

| Approaching Disorder | |

| Barely Coordinated | |

| Moderate Coordination | |

| Good Coordination | |

| Excellent Coordination |

| Category | Selected Driving Factor Indicator | Rationale for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Port Construction Level | Number of Berths () | Reflects the level of port infrastructure construction |

| Port Operation Level | Cargo Throughput () | Reflects port scale and service capacity |

| Container Throughput () | ||

| Economic Development Level | Per Capita GDP () | Reflects the degree of factor input |

| Degree of Openness | Foreign Trade Volume () | Reflects the level of economic openness |

| Government Regulation | Total Fixed Asset Investment () | Reflects social development guarantees |

| Service Industry Resource Agglomeration | Resident Population () | Reflects population concentration scale |

| Proportion of Tertiary Industry Employment () | Reflects employment absorption capacity | |

| Science and Technology | Proportion of R&D Personnel in Each City to Provincial Total () | Reflects the level of technological innovation |

| Year | Nanjing | Wuxi | Xuzhou | Changzhou | Suzhou | Nantong | Lianyungang | Huaian | Yancheng | Yangzhou | Zhenjiang | Taizhou | Suqian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 0.9774 | 0.9488 | 0.8463 | 0.7707 | 0.8377 | 0.9661 | 0.4442 | 0.8657 | 0.7991 | 0.8430 | 0.9829 | 0.6051 | 0.2528 |

| 2016 | 0.9718 | 0.9415 | 0.8345 | 0.7677 | 0.8315 | 0.9783 | 0.4886 | 0.9297 | 0.8454 | 0.8758 | 0.9770 | 0.6298 | 0.3947 |

| 2017 | 0.9539 | 0.9009 | 0.9128 | 0.7278 | 0.9704 | 0.8479 | 0.4054 | 0.8194 | 0.6573 | 0.7941 | 0.9390 | 0.6664 | 0.2816 |

| 2018 | 0.9647 | 0.8499 | 0.9005 | 0.7449 | 0.9870 | 0.8763 | 0.4594 | 0.8892 | 0.7173 | 0.8941 | 0.9215 | 0.6797 | 0.3134 |

| 2019 | 0.9676 | 0.8440 | 0.9040 | 0.7470 | 0.9894 | 0.8689 | 0.4692 | 0.8878 | 0.7158 | 0.8852 | 0.9012 | 0.6913 | 0.3551 |

| 2020 | 0.9617 | 0.9521 | 0.8721 | 0.7427 | 0.9855 | 0.8592 | 0.4645 | 0.9534 | 0.7152 | 0.8760 | 0.8950 | 0.6815 | 0.4065 |

| 2021 | 0.9673 | 0.9473 | 0.8533 | 0.7338 | 0.9619 | 0.8418 | 0.4584 | 0.9813 | 0.7715 | 0.8843 | 0.9143 | 0.7308 | 0.4487 |

| 2022 | 0.9532 | 0.9552 | 0.8412 | 0.7030 | 0.9599 | 0.8342 | 0.4234 | 0.9644 | 0.7600 | 0.8727 | 0.9187 | 0.7219 | 0.4607 |

| 2023 | 0.9534 | 0.9488 | 0.8246 | 0.6755 | 0.9559 | 0.8324 | 0.4337 | 0.9399 | 0.7557 | 0.8750 | 0.9137 | 0.6905 | 0.5060 |

| Average | 0.9634 | 0.9209 | 0.8655 | 0.7348 | 0.9421 | 0.8784 | 0.4497 | 0.9145 | 0.7486 | 0.8667 | 0.9293 | 0.6774 | 0.3799 |

| City | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanjing | 0.7286 | 0.7219 | 0.7722 | 0.7820 | 0.7939 | 0.7733 | 0.7247 | 0.7143 | 0.7092 | 0.7467 |

| Wuxi | 0.5619 | 0.5551 | 0.6352 | 0.6545 | 0.6456 | 0.5743 | 0.5508 | 0.5878 | 0.5956 | 0.5956 |

| Xuzhou | 0.3293 | 0.3405 | 0.3652 | 0.3575 | 0.3661 | 0.3422 | 0.3352 | 0.3333 | 0.3286 | 0.3442 |

| Changzhou | 0.3694 | 0.3511 | 0.4022 | 0.4214 | 0.4317 | 0.4270 | 0.4199 | 0.4108 | 0.4085 | 0.4002 |

| Suzhou | 0.8289 | 0.8300 | 0.9468 | 0.9658 | 0.9769 | 0.9721 | 0.9401 | 0.9332 | 0.9289 | 0.9248 |

| Nantong | 0.5904 | 0.5955 | 0.6540 | 0.6567 | 0.6745 | 0.6937 | 0.6767 | 0.6703 | 0.6624 | 0.6527 |

| Lianyungang | 0.4837 | 0.4553 | 0.4494 | 0.4519 | 0.4658 | 0.4586 | 0.4436 | 0.4383 | 0.4562 | 0.4559 |

| Huaian | 0.3222 | 0.3282 | 0.3701 | 0.3712 | 0.3550 | 0.3232 | 0.3014 | 0.3038 | 0.3020 | 0.3308 |

| Yancheng | 0.4024 | 0.4093 | 0.4496 | 0.4380 | 0.4537 | 0.4456 | 0.4492 | 0.4458 | 0.4452 | 0.4376 |

| Yangzhou | 0.4084 | 0.3984 | 0.4265 | 0.3962 | 0.4048 | 0.4107 | 0.3966 | 0.4028 | 0.4122 | 0.4063 |

| Zhenjiang | 0.3909 | 0.3903 | 0.4320 | 0.4160 | 0.4333 | 0.4329 | 0.4175 | 0.4099 | 0.4101 | 0.4148 |

| Taizhou | 0.4952 | 0.5107 | 0.5349 | 0.5447 | 0.5536 | 0.5459 | 0.5354 | 0.5395 | 0.5507 | 0.5345 |

| Suqian | 0.1764 | 0.1612 | 0.1614 | 0.1508 | 0.1415 | 0.1392 | 0.1379 | 0.1404 | 0.1437 | 0.1503 |

| Average | 0.4683 | 0.4652 | 0.5076 | 0.5082 | 0.5151 | 0.5030 | 0.4869 | 0.4869 | 0.4887 |

| Year | Port Operations Lagging | Synchronized Development | Shipping Service Industry Lagging |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Wuxi, Changzhou, Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Taizhou, Suqian | Nanjing | Xuzhou, Suzhou, Zhenjiang |

| 2018 | Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Nantong, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Taizhou, Suqian | Lianyungang, Zhenjiang | Suzhou |

| 2021 | Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Nantong, Lianyungang, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Taizhou, Suqian | Huaian, Zhenjiang | Suzhou |

| 2023 | Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Suqian | None | Suzhou |

| Year | Urban Economy Lagging | Synchronized Development | Shipping Service Industry Lagging |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Taizhou, Suqian | Zhenjiang | Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Suzhou |

| 2018 | Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Suqian | None | Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Suzhou |

| 2021 | Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Suqian | Nanjing, Changzhou | Wuxi, Xuzhou, Suzhou |

| 2023 | Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Suqian | Nanjing, Changzhou | Wuxi, Xuzhou, Suzhou |

| Category | Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | z | P > |z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Construction Level | Number of berths () | 2.19 × 10−4 *** | 3.10 × 10−5 | 7.04 | 0.000 |

| Port Operation Level | Cargo throughput () | 7.42 × 10−6 *** | 7.25 × 10−7 | 10.24 | 0.000 |

| Container throughput () | 1.22 × 10−8 ** | 5.56 × 10−9 | 2.19 | 0.030 | |

| Economic Development Level | Per capita GDP () | 7.13 × 10−7 *** | 2.34 × 10−7 | 3.04 | 0.003 |

| Degree of Openness | Total foreign trade volume () | 4.62 × 10−5 *** | 1.46 × 10−5 | 3.15 | 0.002 |

| Government Regulation | Total fixed asset investment in the whole society () | 2.66 × 10−5 *** | 5.56 × 10−6 | 4.8 | 0.000 |

| Agglomeration of Service Industry Resources | Permanent resident population () | 2.49 × 10−4 *** | 4.36 × 10−5 | 5.7 | 0.000 |

| Proportion of employment in the tertiary industry () | 0.0019 * | 0.0011 | 1.72 | 0.078 | |

| Science and Technology | Proportion of R&D personnel in each city relative to the province () | 0.0466 | 0.1236 | 0.38 | 0.707 |

| Other | _cons | 0.1012 *** | 0.0361 | 2.8 | 0.006 |

| Category | Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | z | P > |z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Construction Level | Number of berths () | 2.09 × 10−4 *** | 3.08 × 10−5 | 6.78 | 0.000 |

| Port Operation Level | Cargo throughput () | 7.17 × 10−6 *** | 7.21 × 10−7 | 9.94 | 0.000 |

| Container throughput () | 1.47 × 10−8 *** | 5.58 × 10−9 | 2.64 | 0.009 | |

| Economic Development Level | Per capita GDP () | 9.302 × 10−7 *** | 3.06 × 10−7 | 3.04 | 0.000 |

| Degree of Openness | Total foreign trade volume () | 4.349 × 10−6 *** | 1.30 × 10−6 | 3.34 | 0.003 |

| Government Regulation | Total fixed asset investment in the whole society () | 3.00 × 10−5 *** | 5.66 × 10−6 | 5.3 | 0.000 |

| Agglomeration of Service Industry Resources | Permanent resident population () | 2.66 × 10−4 *** | 4.36 × 10−5 | 6.11 | 0.000 |

| Proportion of employment in the tertiary industry () | 2.03 × 10−3 * | 0.001124 | 1.81 | 0.082 | |

| Science and Technology | Proportion of R&D personnel in each city relative to the province () | 0.081046 | 0.122598 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| Industrial Development | Industrial added value | 2.01 × 10−5 | 8.76 × 10−6 | 2.3 | 0.113 |

| Other | _cons | 0.1023969 *** | 0.03555 | 2.88 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Du, L.; Xing, H.; Tang, J.; Ma, C. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Drivers of Shipping Service Industry Agglomeration and Port–City Synergy: Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411366

Zhang T, Du L, Xing H, Tang J, Ma C. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Drivers of Shipping Service Industry Agglomeration and Port–City Synergy: Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411366

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Tong, Linan Du, Husong Xing, Jimeng Tang, and Cunrui Ma. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Drivers of Shipping Service Industry Agglomeration and Port–City Synergy: Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411366

APA StyleZhang, T., Du, L., Xing, H., Tang, J., & Ma, C. (2025). Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Drivers of Shipping Service Industry Agglomeration and Port–City Synergy: Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability, 17(24), 11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411366