Sustainable Maritime Decarbonization: A Review of Hydrogen and Ammonia as Future Clean Marine Energies

Abstract

1. Introduction

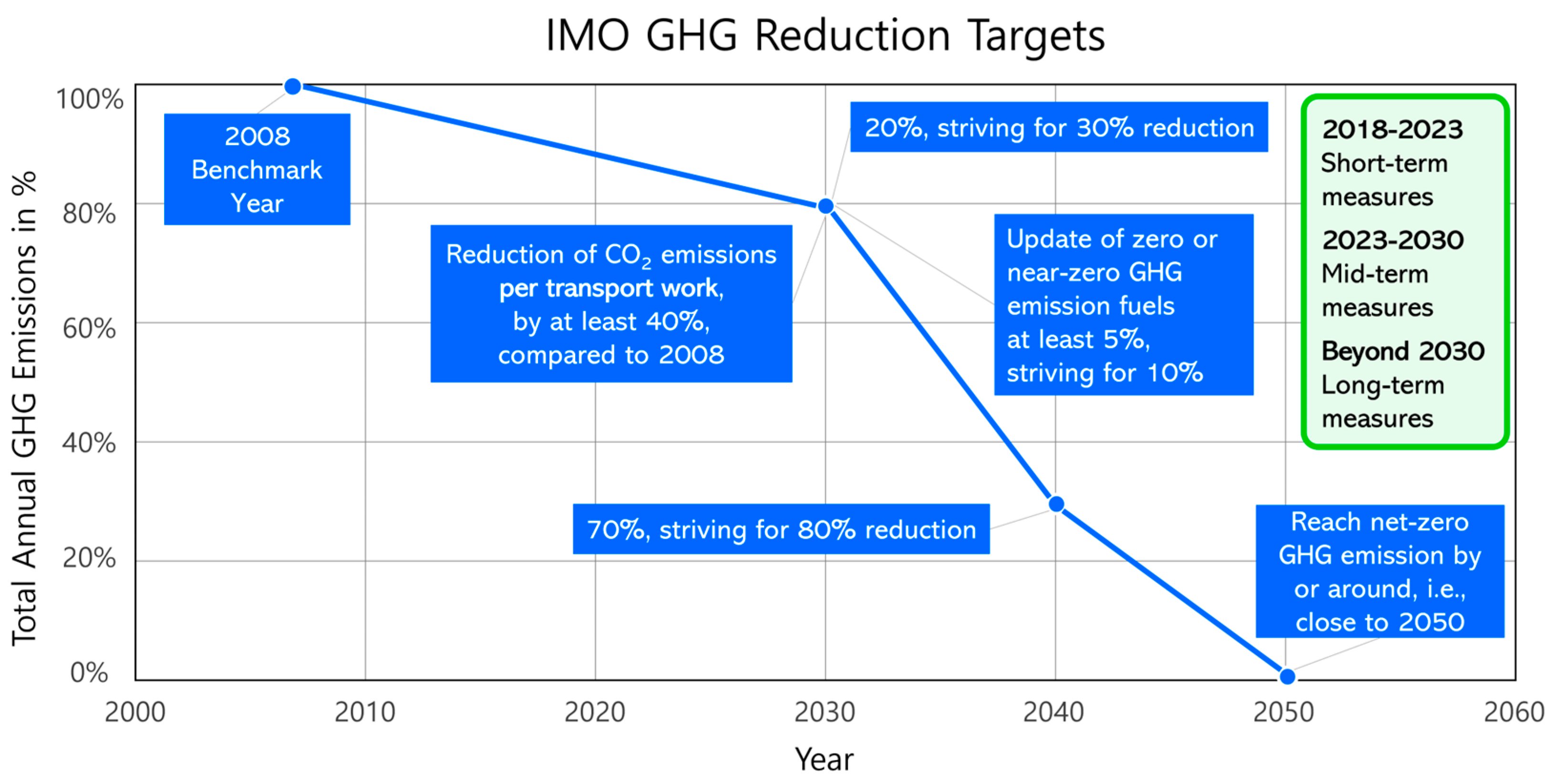

1.1. Background

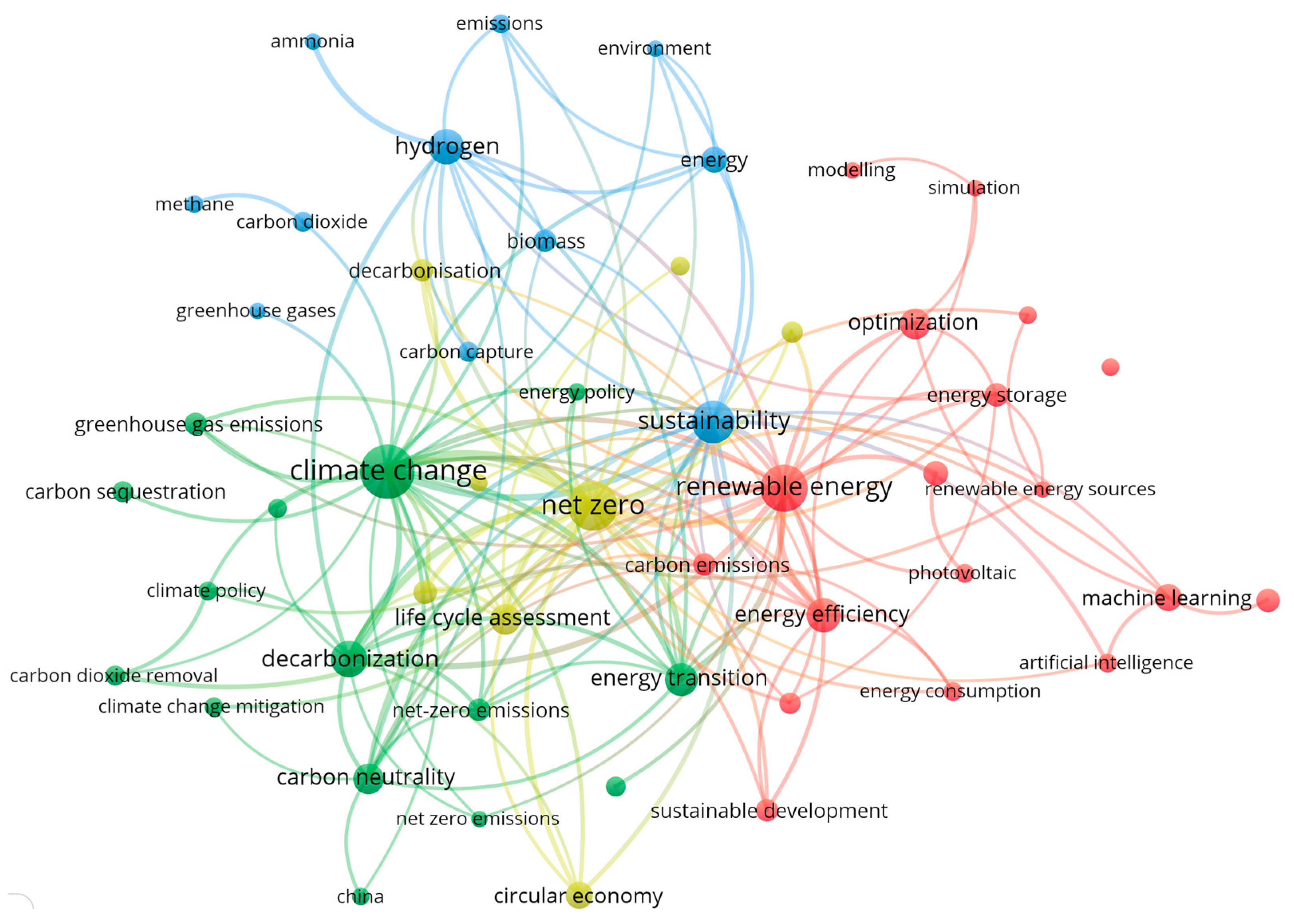

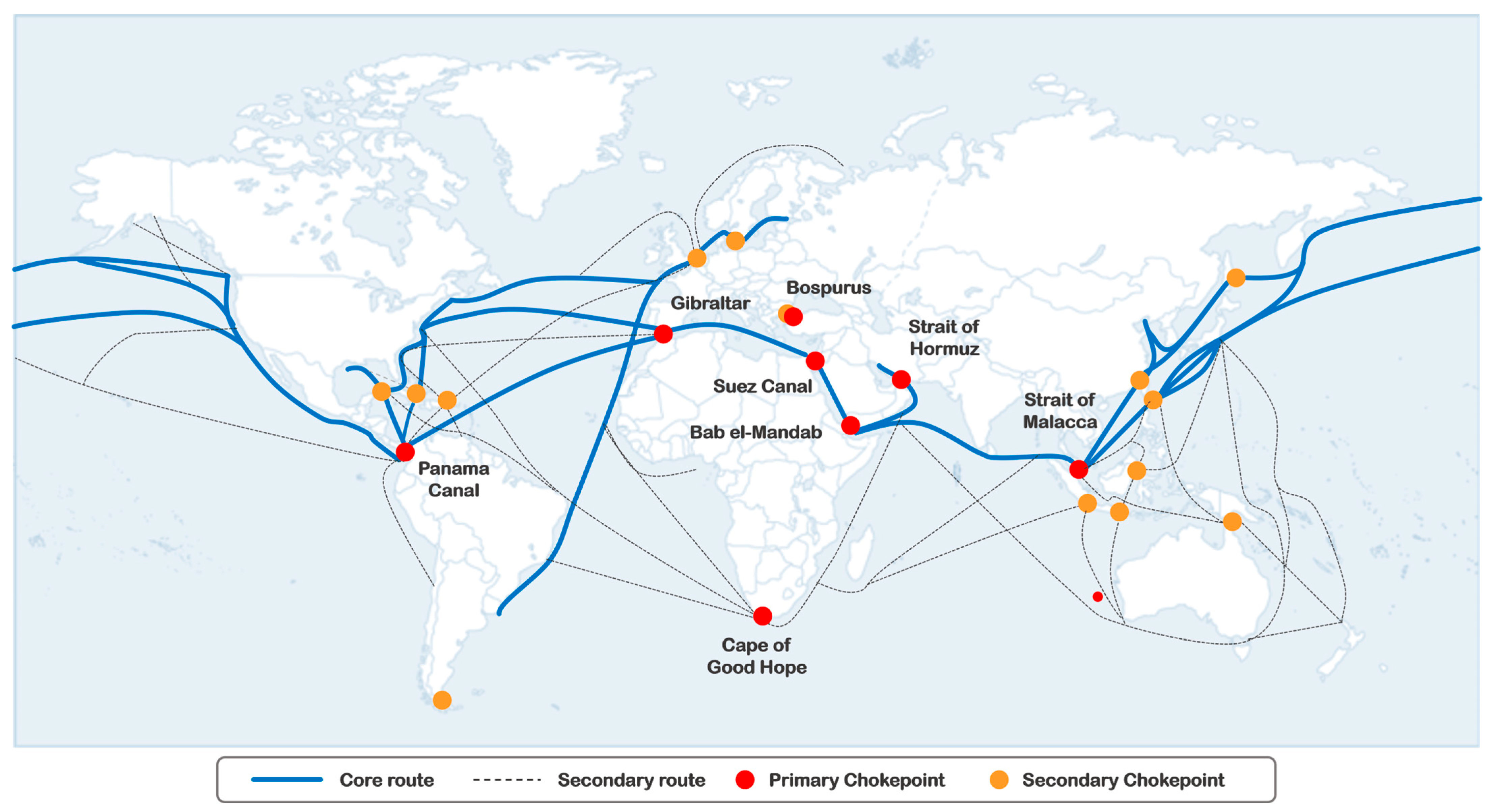

1.2. Bibliometric Analysis

1.3. Objective and Research Scope

1.4. Research Methodology

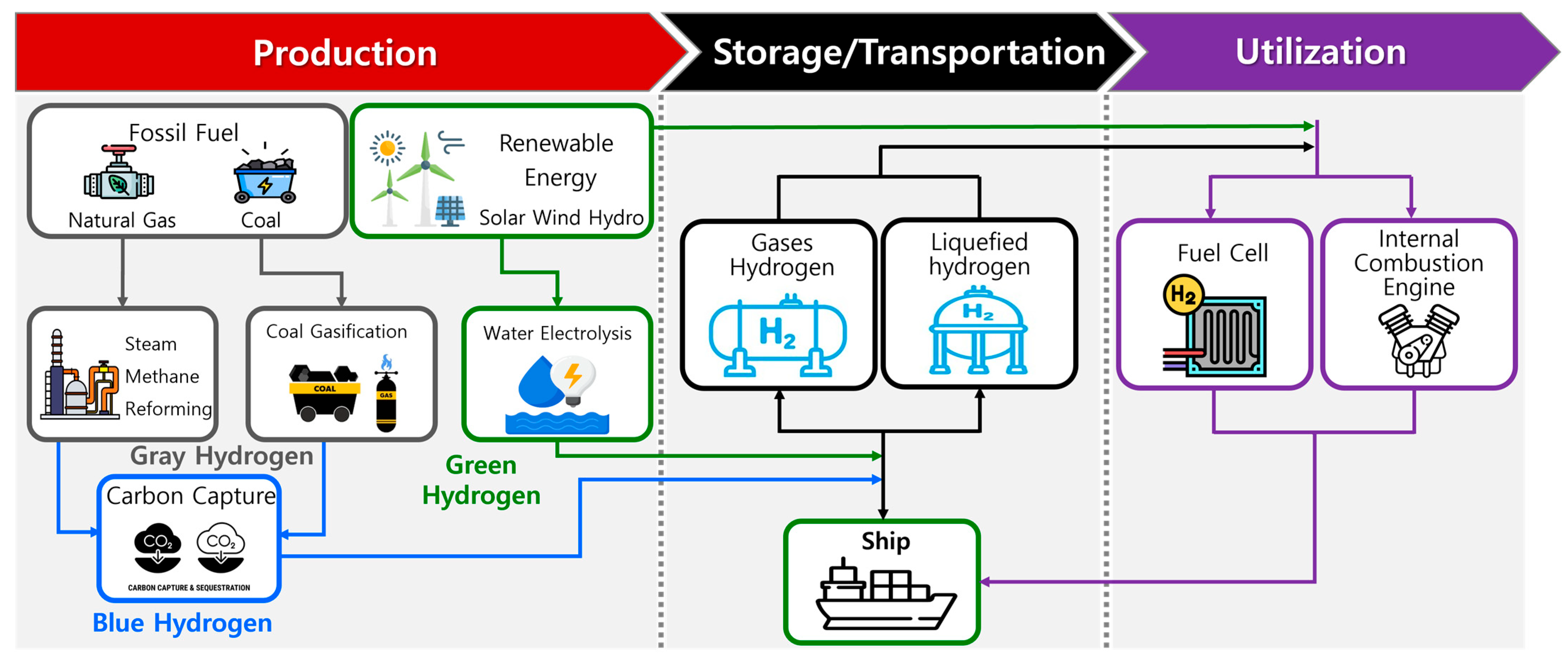

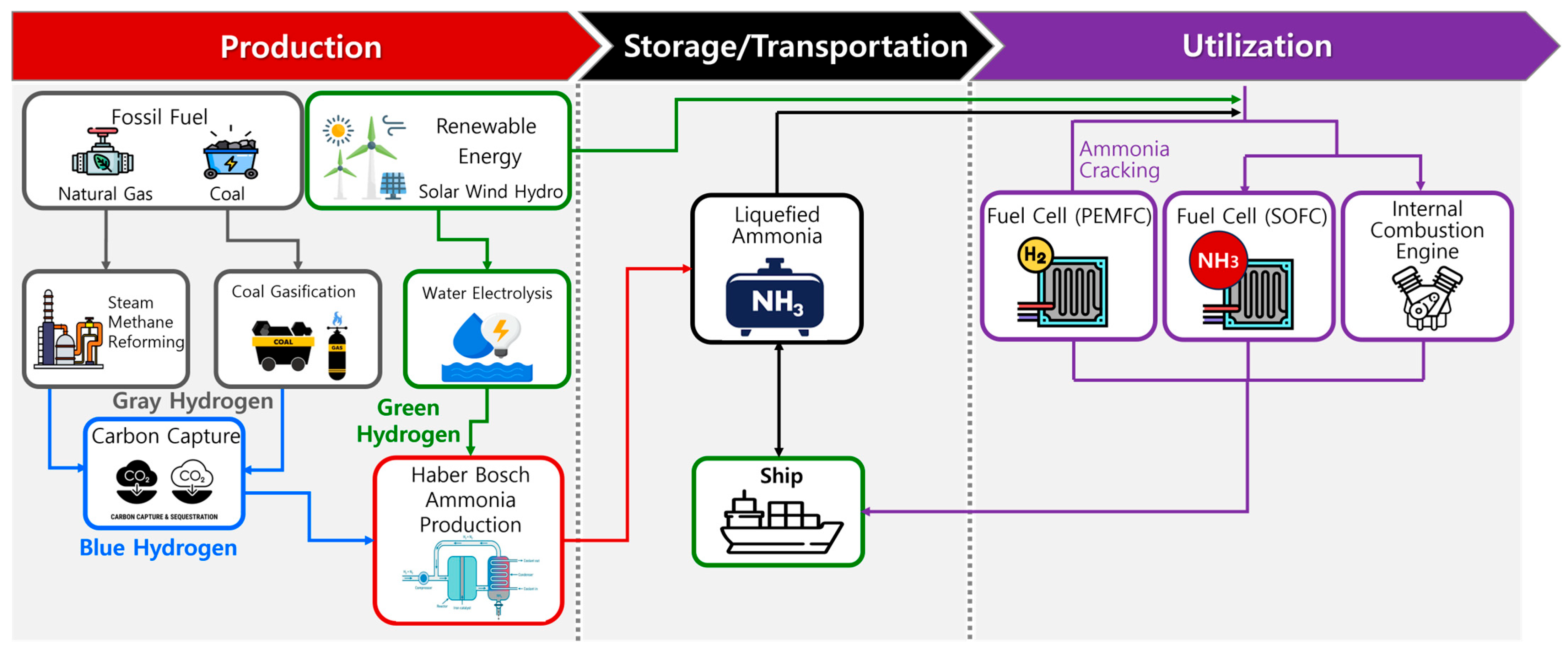

2. Methods of Hydrogen and Ammonia Production

2.1. Hydrogen Production Technologies

2.2. Ammonia Production Technologies

3. Utilization of Hydrogen and Ammonia in the Maritime Industry

3.1. Hydrogen Utilization

3.2. Ammonia Utilization

4. Potential Issues for Utilization of Hydrogen and Ammonia

4.1. Economics of Hydrogen and Ammonia

4.2. Policies Dealing with Hydrogen and Ammonia

- Revision of the interim guidelines for the safety of ships using methyl/ethyl alcohol as fuel (approval expected 2027)

- Revision of the interim guidelines for the safety of ships using fuel cell power installations (approval expected 2028)

- Development of the interim guidelines for the safety of ships using onboard carbon capture and storage systems (approval expected 2029)

4.3. Geopolitical Landscape and Energy Security

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks

- Energy density vs. safety: While ammonia offers superior energy logistics, its toxicity risks necessitate substantial investments in complex safety protocols and vessel design modifications; meanwhile, hydrogen faces extreme volumetric storage challenges at sea.

- Economic readiness: The current high production cost of clean fuels is the single greatest barrier to their widespread adoption. This economic gap underscores the critical need for a universal and robust carbon pricing mechanism to achieve cost parity with conventional fuels.

- Policy and regulation: Existing IMO regulations successfully drive the mandate for change, but they must be immediately complemented by decisive financial and governmental support policies to de-risk infrastructure investment and stabilize the nascent clean fuel market.

- Geopolitical shift: The transition will fundamentally restructure global energy supply chains, creating new geopolitical dependencies on regions with high renewable energy potential, and necessitating a proactive analysis of energy security along major shipping routes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Review of maritime transport 2023. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, New York, NY, USA, 27 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Balcombe, P.; Brierley, J.; Lewis, C.; Skatvedt, L.; Speirs, J.; Hawkes, A.; Staffell, I. How to decarbonise international shipping: Options for fuels, technologies and policies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, P.R.; Skea, J.; Slade, R.; Fradera, R.; Pathak, M.; Al Khourdajie, A.; Belkacemi, M.; van Diemen, R.; Hasija, A.; Lisboa, G.; et al. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: London, UK, 2022.

- Wang, Y.; Wright, L.A. A comparative review of alternative fuels for the maritime sector: Economic, technology, and policy challenges for clean energy implementation. World 2021, 2, 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheliotis, M.; Boulougouris, E.; Trivyza, N.L.; Theotokatos, G.; Livanos, G.; Mantalos, G.; Stubos, A.; Stamatakis, E.; Venetsanos, A. Review on the safe use of ammonia fuel cells in the maritime industry. Energies 2021, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fransen, T.; Welle, B.; Gorguinpour, C.; McCall, M.; Song, R.; Tankou, A. Enhancing NDCs: Opportunities in Transport; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doelle, M.; Chircop, A. Decarbonizing international shipping: An appraisal of the IMO’s Initial Strategy. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2019, 28, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. Initial IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships, Resolution MEPC. 304 (72); International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, S.; Mason, J.; Larkin, A. The urgent case for stronger climate targets for international shipping. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Xia, C. A prompt decarbonization pathway for shipping: Green hydrogen, ammonia, and methanol production and utilization in marine engines. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships, Resolution MEPC. 377 (80); International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. ABS Regulatory News—MEPC 80 Brief; American Bureau of Shipping: Spring, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, H.; Stuart, C.; Spence, S.; Chen, H. Alternative fuel options for low carbon maritime transportation: Pathways to 2050. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Dong, T.; Schönborn, A.; Ölçer, A.I.; Dalaklis, D. A cost-benefit analysis of the use of ammonia and hydrogen as marine fuels. In Proceedings of the International Maritime and Logistics Conference “Marlog 12”, Alexandria, Egypt, 12–14 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D.T.; Schönborn, A.; Christodoulou, A.; Ölcer, A.I.; González-Celis, J. Life cycle assessment of ammonia/hydrogen-driven marine propulsion. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2024, 238, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstad, E.; Lagemann, B.; Rialland, A.; Gamlem, G.M.; Valland, A. Reduction of maritime GHG emissions and the potential role of E-fuels. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 101, 103075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, G.; Finney, H.; Fischer, S.; Sikora, I.; McQuillen, J.; Ash, N.; Shakeel, H. Technological, Operational and Energy Pathways for Maritime Transport to Reduce Emissions Towards 2050; Ricardo Energy & Environment: West Sussex, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, T.I.; Weiss, N.D.; van Dyk, S.; van Thuijl, E.; Thomsen, S.T. Progress Towards Biofuels for Marine Shipping: Status and Identification of Barriers for Utilization of Advanced Biofuels in the Marine Sector; International Energy Agency Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni, G.; Scamardella, F.; Gualeni, P.; Canepa, E. Comparative analysis among different alternative fuels for ship propulsion in a well-to-wake perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: London, UK, 2021.

- Selvi Rajaram, P.; Kandasamy, A.; Arokiasamy Remigious, P. Effectiveness of oxygen enriched hydrogen-hho gas addition on direct injection diesel engine performance, emission and combustion characteristics. Therm. Sci. 2014, 18, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Green Hydrogen: A Guide to Policy Making; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DNV. Ammonia as a Marine Fuel: Safety Handbook; Det Norske Veritas: Høvik, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Ammonia as Marine Fuel; American Bureau of Shipping: Spring, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Atilhan, S.; Park, S.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Atilhan, M.; Moore, M.; Nielsen, R.B. Green hydrogen as an alternative fuel for the shipping industry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen Factor; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.-S.; Park, C.; Kim, B.; Vakili, S. Decarbonization Roadmap for the Domestic Fleet of the Republic of Korea; World Maritime University: Malmö, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A. Exploratory bibliometrics: Using VOSviewer as a preliminary research tool. Publications 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loe, P.Y.A.; Kim, M.; Jin, C.; Bakti, F.P.; Kim, D.K. Recent advances in Discrete-Module-Beam-based hydroelasticity method as an efficient tool approach for continuous very large floating structures. Ocean Eng. 2025, 340, 122229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV. Maritime Forecast to 2050; Det Norske Veritas: Høvik, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Global Hydrogen Review 2024; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aboosi, F.Y.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Moore, M.; Nielsen, R.B. Renewable ammonia as an alternative fuel for the shipping industry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-k.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-S. Simulation and analysis of a fuel supply system with vent control system for ammonia fueled ships. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 48, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.H.; Duong, P.A.; Ryu, B.R.; Kang, H. A study on performances of SOFC integrated system for hydrogen-fueled vessel. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2023, 47, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.-T.; Davies, P.; Wright, L. Ammonia as a marine fuel: Likelihood of ammonia releases. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2023, 47, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Charting a Course for Decarbonizing Maritime Transport; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MMMCZCS. Impact Report 2023/2024: Showing the World It Is Possible; Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DNV. Energy-Efficiency Measures and Technologies; Det Norske Veritas: Høvik, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Methanol Institute. Methanol Fuelled Vessels on the Water and on the Way; Methanol Institute: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ushakov, S.; Stenersen, D.; Einang, P.M. Methane slip from gas fuelled ships: A comprehensive summary based on measurement data. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 24, 1308–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, B.; Beecken, J.; Vermeulen, R.; Sturrup, E.; Paschinger, P.; Osipova, L.; Gore, K.; Delahaye, A.; Verhagen, V.; Knudsen, B. Fugitive and Unburned Methane Emissions from Ships (FUMES); International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, N.; Comer, B.; Zhou, Y.; Clark, N.; Rutherford, D. The Climate Implications of Using LNG as a Marine Fuel; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020.

- Gibson, J.; Eby, P.; Jaggi, A. Natural isotope fingerprinting of produced hydrogen and its potential applications to the hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 66, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersch, M.; Sunny, N.; Dejan, R.; Ku, A.Y.; Wilson, G.; O’Reilly, S.; Soloveichik, G.; Wyatt, J.; Mac Dowell, N. A comparative techno-economic assessment of blue, green, and hybrid ammonia production in the United States. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 1495–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzell, M.C. The colors of ammonia. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 2920–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incer-Valverde, J.; Korayem, A.; Tsatsaronis, G.; Morosuk, T. “Colors” of hydrogen: Definitions and carbon intensity. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, G.W.; Dresselhaus, M.S. The hydrogen fuel alternative. MRS Bull. 2008, 33, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadidi, B.; Najafi, G.; Yusaf, T. A review of hydrogen as a fuel in internal combustion engines. Energies 2021, 14, 6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeli, K.; Nachtane, M.; Faik, A.; Saifaoui, D.; Boulezhar, A. How green hydrogen and ammonia are revolutionizing the future of energy production: A comprehensive review of the latest developments and future prospects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Roccotelli, M.; Sahu, U.K. Hydrogen fuel for future mobility: Challenges and future aspects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, R.; Rosen, M.; Dincer, I. Assessment of CO2 capture options from various points in steam methane reforming for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 20266–20275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, L. Hydrogen Production: Overview and Issues for Congress; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Azim, R.M.; Torii, S. Exploring the potential of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for transportation. Open Eng. 2024, 14, 20240024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Su, J.; Somorjai, G.A. Catalytic hydrogen production from methane: A review on recent progress and prospect. Catalysts 2020, 10, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Zhang, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X. Recent progress on hydrogen-rich syngas production from coal gasification. Processes 2023, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midilli, A.; Kucuk, H.; Topal, M.E.; Akbulut, U.; Dincer, I. A comprehensive review on hydrogen production from coal gasification: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 25385–25412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlissel, D.; Wamsted, D.; Mattei, S.; Mawji, O. Reality Check on CO2 Emissions Capture at Hydrogen-From-Gas Plants; Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis: Valley City, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, U.Y. Future of hydrogen as an alternative fuel for next-generation industrial applications; challenges and expected opportunities. Energies 2022, 15, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, D.; Bertagni, M.; Porporato, A. The water footprint of hydrogen production. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Dincer, I. A comprehensive review on power-to-gas with hydrogen options for cleaner applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 31511–31522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, F.; Dincer, I. Assessment and optimization of an integrated wind power system for hydrogen and methane production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, J.; Turek, T. Alkaline water electrolysis powered by renewable energy: A review. Processes 2020, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, A.S.; Hamdan, M.O.; Abu-Nabah, B.A.; Elnajjar, E. A review on recent trends, challenges, and innovations in alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 64, 599–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.A. Green hydrogen from anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 36, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züttel, A.; Remhof, A.; Borgschulte, A.; Friedrichs, O. Hydrogen: The future energy carrier. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 3329–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicer, Y.; Dincer, I. Clean fuel options with hydrogen for sea transportation: A life cycle approach. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouhi, A.; Rehman, S.; Buker, M.S.; Said, Z. Up-to-date literature review on Solar PV systems: Technology progress, market status and R&D. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132339. [Google Scholar]

- Roga, S.; Bardhan, S.; Kumar, Y.; Dubey, S.K. Recent technology and challenges of wind energy generation: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jin, C.; Kim, M.-H. Systematic comparisons among OpenFAST, Charm3D-FAST simulations and DeepCWind model test for 5 MW OC4 semisubmersible offshore wind turbine. Ocean Syst. Eng. 2023, 13, 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.; Kim, M.; Jin, C. Impact of hull flexibility on the global performance of a 15 MW concrete-spar floating offshore wind turbine. Mar. Struct. 2025, 100, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin Surjadi, F.; Bakti, F.P.; Jin, C.; Simamora, P.K.P. Global response performance of HDPE based offshore floating solar farm by using beam-floater model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Singapore, 9–14 June 2024; p. V007T009A095. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Jin, C.; Jung, D.; Kim, S. Mooring tension estimation for multi-connected floating photovoltaic arrays via LSTM networks. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2025, 211, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Raimondi, P.P.; Scita, R.; Hafner, M. The role of green and blue hydrogen in the energy transition—A technological and geopolitical perspective. Sustainability 2020, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanovic, A.; Sayer, M.; Haas, R. The economics and the environmental benignity of different colors of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 24136–24154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurien, C.; Mittal, M. Review on the production and utilization of green ammonia as an alternate fuel in dual-fuel compression ignition engines. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 251, 114990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaj, K.; Kupecki, J.; Malecha, Z.; Morawski, A.; Skrzypkiewicz, M.; Stanclik, M.; Chorowski, M. Ammonia as a potential marine fuel: A review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 44, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, N.; Bañares-Alcántara, R. Green ammonia as a spatial energy vector: A review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 2814–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinks, H.; Hektor, E.A. Ammonia as a Marine Fuel; Det Norske Veritas and Germanischer Lloyd: Høvik, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Inal, O.B.; Zincir, B.; Deniz, C. Investigation on the decarbonization of shipping: An approach to hydrogen and ammonia. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 19888–19900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, V.; Noussan, M.; Chiaramonti, D. The potential role of ammonia for hydrogen storage and transport: A critical review of challenges and opportunities. Energies 2023, 16, 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlanés, N.; Katikaneni, S.P.; Paglieri, S.N.; Harale, A.; Solami, B.; Sarathy, S.M.; Gascon, J. A technological roadmap to the ammonia energy economy: Current state and missing technologies. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patonia, A.; Poudineh, R. Ammonia as a Storage Solution for Future Decarbonized Energy Systems; Oxford Institute for Energy Studies: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, R.H.; Anderson, J.E.; Wallington, T.J. Outlook for ammonia as a sustainable transportation fuel. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 4830–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Chen, X.; Qin, J.; Wu, P.; Jia, L. The state-of-the-art progress on the forms and modes of hydrogen and ammonia energy utilization in road transportation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zincir, B. A short review of ammonia as an alternative marine fuel for decarbonised maritime transportation. In Proceedings of the ICEESEN2020, Kayseri, Turkey, 19–21 November 2020; pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Hill, A.K.; Torrente-Murciano, L. Current and future role of Haber–Bosch ammonia in a carbon-free energy landscape. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Ammonia Technology Roadmap: Towards More Sustainable Nitrogen Fertiliser Production; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Roh, G.; Lee, S.; Choung, C.; Kang, H. Comparative life cycle assessments and economic analyses of alternative marine fuels: Insights for practical strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalaris, I.; Jeong, B.; Jang, H. Application of parametric trend life cycle assessment for investigating the carbon footprint of ammonia as marine fuel. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.S.; Silva, V.; Rocha, R.C.; Hall, M.J.; Costa, M.; Eusébio, D. Ammonia as an energy vector: Current and future prospects for low-carbon fuel applications in internal combustion engines. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjono, M.; Stevani, I.; Siswanto, G.A.; Adhitya, A.; Halim, I. Assessing the feasibility of gray, blue, and green ammonia productions in Indonesia: A techno-economic and environmental perspective. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2023, 12, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E.; Nwakile, C.; Hammed, V.O. Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies: Evaluating the effectiveness of advanced CCUS solutions for reducing CO2 emissions. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 18, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue Ammonia Fuel: Usage, Projects and Future. Available online: https://energytracker.asia/blue-ammonia-fuel (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Ammonia Energy Association. Global Project List: Low-Emission Ammonia Plants (LEAP); Ammonia Energy Association: Ashburn, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CF Industries Announces Joint Venture with JERA Co., Inc., and Mitsui & Co., Ltd., for Production and Offtake of Low-Carbon Ammonia. Available online: https://www.cfindustries.com/newsroom/2025/blue-point-joint-venture (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Lee, B.; Winter, L.R.; Lee, H.; Lim, D.; Lim, H.; Elimelech, M. Pathways to a green ammonia future. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 3032–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewable Hydrogen Plant at Herøya. Available online: https://www.yara.com/news-and-media/media-library/press-kits/renewable-hydrogen-plant-heroya-norway/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Envision Delivers on World’s Largest Green Hydrogen and Ammonia Plant with Off-Grid Renewable System. Available online: https://en.antaranews.com/news/367709/envision-delivers-on-worlds-largest-green-hydrogen-and-ammonia-plant-with-off-grid-renewable-system (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- NEOM Green Hydrogen Project. Available online: https://saudipedia.com/en/article/411/economy-and-business/projects/neom-green-hydrogen-project (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- First Ammonia and Uniper Announced Cooperation on Green Ammonia Project in Texas. Available online: https://www.uniper.energy/news/first-ammonia-and-uniper-announced-cooperation-on-green-ammonia-project-in-texas (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Seddiek, I.S.; Elgohary, M.M.; Ammar, N.R. The hydrogen-fuelled internal combustion engines for marine applications with a case study. Brodogr. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. Res. Dev. 2015, 66, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Di Micco, S.; Mastropasqua, L.; Cigolotti, V.; Minutillo, M.; Brouwer, J. A framework for the replacement analysis of a hydrogen-based polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell technology on board ships: A step towards decarbonization in the maritime sector. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 267, 115893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Feng, L. Optimization of injection system for a medium-speed four-stroke spark-ignition marine hydrogen engine. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 19289–19297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.N.; Sahu, K.B.; Ghadai, S.K.; Kumar, C.B. A review of performance and emissions of diesel engine operating on dual fuel mode with hydrogen as gaseous fuel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 27394–27407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A. A high-efficiency internal combustion engine using oxygen and hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 50, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernat, A.; Pana, C.; Negurescu, N.; Lazaroiu, G.; Nutu, C.; Fuiorescu, D. Hydrogen—An alternative fuel for automotive diesel engines used in transportation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, J.; Davíðsdóttir, B.; Fridell, E.; Jivén, K.; Yum, K.K.; Latapí, M.; Lundström, H.; Parsmo, R.; Stenersen, D.; Wimby, P.; et al. HOPE—Hydrogen Fuel Cells Solutions in Nordic Shipping; Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elkafas, A.G.; Rivarolo, M.; Gadducci, E.; Magistri, L.; Massardo, A.F. Fuel cell systems for maritime: A review of research development, commercial products, applications, and perspectives. Processes 2022, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, J. Integration of Hydrogen Fuel Cells in Marine Power Systems. Master’s Thesis, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard. Flagships Project: Hydrogen-Powered Container Vessel Completes Initial Waterway Trials. Available online: https://blog.ballard.com/marine/hydrogen-powered-container-vessel-completes-initial-waterway-trials#:~:text=Retrofitted%20with%20a%20new%20zero,2%7D%20annually (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Guan, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Ye, Q.; Fan, H. A 500 kW hydrogen fuel cell-powered vessel: From concept to sailing. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 89, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMSA. Potential of Hydrogen as Fuel for Shipping; European Maritime Safety Agency: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay, C.J.; Turnock, S.; Hudson, D. A Comparison of hydrogen and ammonia for future long distance shipping fuels. In Proceedings of the LNG/LPG and Alternative Fuel Ships, London, UK, 29–30 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Levikhin, A.; Boryaev, A. Low-carbon ammonia-based fuel for maritime transport. Results Eng. 2025, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, P.-C.; Yang, H. Alternative gaseous fuels for marine vessels towards zero-carbon emissions. Gases 2023, 3, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Full-Scale Ammonia Engine Runs at 100% Load. Available online: https://www.man-es.com/company/press-releases/press-details/2025/01/30/full-scale-ammonia-engine-runs-at--100--load (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Krook, T.; Engsbo, R.; Torrkulla, J.; Hattar, C. Ammonia-powered future: Introducing Wärtsilä 25. In Proceedings of the CIMAC Congress 25, Zurich, Switzerland, 19–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- HD Hyundai Develops Direct Injection Ammonia Dual-Fuel Engine. Available online: https://datamarnews.com/noticias/hd-hyundai-develops-direct-injection-ammonia-dual-fuel-engine/#:~:text=Since%20the%20examination%20and%20compliance,of%20the%20HiMSEN%20ammonia%20engine (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Successful Propulsion and Manoeuvrability Trials by Fortescue’s Dual-Fuelled Ammonia-Powered Vessel in the Port of Singapore. Available online: https://www.mpa.gov.sg/media-centre/details/successful-propulsion-and-manoeuvrability-trials--by-fortescue-s-dual-fuelled-ammonia-powered-vessel-in-the-port-of-singapore?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- DNV Awards Certificates for Fortescue’s Dual-Fuelled Ammonia-Powered Vessel During Singapore Maritime Week. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/news/2024/dnv-awards-certificates-for-fortescues-dual-fuelled-ammonia-powered-vessel-during-singapore-maritime-week/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- World’s First Commercial-Use Ammonia-Fueled Tugboat Completes Three-Month Demonstration Voyage. Available online: https://www.nyk.com/english/news/2025/20250328_02.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- LEAD: Ammonia-Fueled Vessels. Available online: https://ammoniaenergy.org/lead/vessels/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Jin, S.; Wu, B.; Zi, Z.; Yang, P.; Shi, T.; Zhang, J. Effects of fuel injection strategy and ammonia energy ratio on combustion and emissions of ammonia-diesel dual-fuel engine. Fuel 2023, 341, 127668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Shu, B. Recent progress on combustion characteristics of ammonia-based fuel blends and their potential in internal combustion engines. Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2023, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, T.; Chen, R.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, N.; Li, S.; Kuang, M.; Yang, W. Ammonia marine engine design for enhanced efficiency and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, A.J.; Kong, S.-C. Combustion and emissions characteristics of compression-ignition engine using dual ammonia-diesel fuel. Fuel 2011, 90, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Long, W.; Xie, C.; Tian, H. After-Treatment Technologies for Emissions of Low-Carbon Fuel Internal Combustion Engines: Current Status and Prospects. Energies 2025, 18, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veldhuizen, B.; Van Biert, L.; Aravind, P.V.; Visser, K. Solid oxide fuel cells for marine applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 5163448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, S.; Cigolotti, V.; Mastropasqua, L.; Brouwer, J.; Minutillo, M. Ammonia-powered ships: Concept design and feasibility assessment of powertrain systems for a sustainable approach in maritime industry. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Medina, A.; Amer-Hatem, F.; Azad, A.K.; Dedoussi, I.; De Joannon, M.; Fernandes, R.; Glarborg, P.; Hashemi, H.; He, X.; Mashruk, S. Review on ammonia as a potential fuel: From synthesis to economics. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 6964–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Pfeifer, M.; Holtz, D.; Müller, K. Comparison of green ammonia and green hydrogen pathways in terms of energy efficiency. Fuel 2024, 357, 129843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.; Abdulrahman, G.A. A recent comprehensive review of fuel cells: History, types, and applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 7271748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, J.M.M.; Santos, D.M. The hydrogen color spectrum: Techno-economic analysis of the available technologies for hydrogen production. Gases 2023, 3, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Green Hydrogen Auctions: A Guide to Design; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, A.; McStay, D.; Rooney, D.; Robertson, P.; Foley, A. Techno-economic analysis to identify the optimal conditions for green hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV. Hydrogen Forecast to 2050; Det Norske Veritas: Høvik, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Díaz, M.T.; Chávez Oróstica, H.; Guajardo, J. Economic analysis: Green hydrogen production systems. Processes 2023, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsted, D.; Feaster, S.; Mattei, S.; Sanzillo, T. Blue Hydrogen Has Extremely Limited Future in U.S. Energy Market; Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis: Valley City, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WEC. Hydrogen Demand and Cost Dynamics; World Energy Council: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pistolesi, C.; Giaconia, A.; Bassano, C.; De Falco, M. Flexible Green Ammonia Production: Impact of Process Design on the Levelized Cost of Ammonia. Fuels 2025, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA; AEA. Innovation Outlook: Renewable ammonia; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Souissi, N. Fueling the Future: A Techno-Economic Evaluation of e-Ammonia Production for Marine Applications; Oxford Institute for Energy Studies: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Walsh, S.D.; Longden, T.; Palmer, G.; Lutalo, I.; Dargaville, R. Optimising renewable generation configurations of off-grid green ammonia production systems considering Haber-Bosch flexibility. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 280, 116790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling Up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5 °C Climate Goal; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chavando, A.; Silva, V.; Cardoso, J.; Eusebio, D. Advancements and challenges of ammonia as a sustainable fuel for the maritime industry. Energies 2024, 17, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.J.; Oh, C. Simulation study on regulatory compliance costs of alternative marine fuels under IMO GHG mid-term measures. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2025, 49, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. Maritime Safety Committee (MSC 105), 20–29 April 2022. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/meetingsummaries/pages/msc-105th-session.aspx (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Fink, L.; Esfeh, S.K.; Depken, J.; Ehlers, S.; Kaltschmitt, M. Powerfuels and alternative fuels in the maritime sector. In Powerfuels: Status and Prospects; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 905–940. [Google Scholar]

- DNV. MO CCC 11: Interim Guidelines for Hydrogen as Fuel Completed. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/news/2025/imo-ccc-11-interim-guidelines-for-hydrogen-as-fuel-completed/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Bradshaw, M.J. Global energy dilemmas: A geographical perspective. Geogr. J. 2010, 176, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. A Pathway to Decarbonise the Shipping Sector by 2050; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Making the Breakthrough: Green Hydrogen Policies and Technology Costs; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vakulchuk, R.; Overland, I. Central Asia is a missing link in analyses of critical materials for the global clean energy transition. One Earth 2021, 4, 1678–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 4D Infrastructure. Global Matters: Green hydrogen—A European Case Study. Available online: https://www.4dinfra.com/insights/articles/global-matters-green-hydrogen-european-case-study?cookies_set=true (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Lee, J.; Sim, M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, C. Strategic pathways to alternative marine fuels: Empirical evidence from shipping practices in South Korea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleimann, D.; Poitiers, N.; Sapir, A.; Tagliapietra, S.; Véron, N.; Veugelers, R.; Zettelmeyer, J. How Europe Should Answer the US Inflation Reduction Act; Bruegel Policy Contribution: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W. Towards growth-driven environmentalism: The green energy transition and local state in China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 117, 103726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, D.; Tolstorebrov, I.; Iwamoto, Y.; Lamb, J.J. Hydrogen and Japan’s Energy Transition: A Blueprint for Carbon Neutrality. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocitarenco, N.; Aneziris, O.; Koromila, I.; Nivolianitou, Z.; Gerbec, M.; Maras, V.; Salzano, E. A Systematic Literature Review on Safety of Ammonia as a Marine Fuel. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2025, 116, 733–738. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Fernandes, R.J.; Turner, J.W.; Emberson, D.R. Life cycle assessment of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for marine internal combustion engines. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 112, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicer, Y.; Dincer, I. Environmental impact categories of hydrogen and ammonia driven transoceanic maritime vehicles: A comparative evaluation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 4583–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gu, B.; Mujeeb-Ahmed, M.; Zhou, P.; Jeong, B.; Wang, H.; Mesbahi, A.; Yang, I. Effectiveness of mechanical ventilation in mitigating ammonia leaks: A safety assessment for ammonia-fuelled ships. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 178, 151568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri Hosseinkhani, N. Green Finance and the Circular Economy Transition: Policy Frameworks, Financial Instruments, and Impact Metrics. Financ. Instrum. Impact Metr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

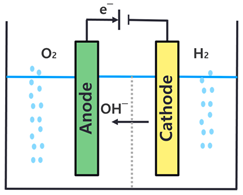

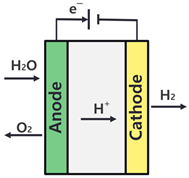

| Specification | AWE | PEMWE |

|---|---|---|

| Operation principle |  |  |

| Anodic reaction | ||

| Cathodic reaction | ||

| Electrolyte | KOH (Liquid) | Polymer (Solid) |

| Operating temperature (°C) | 60–90 | 50–90 |

| Operating pressure (bar) | 2–10 | 15–30 |

| Current density (A/cm2) | 0.2–0.4 | 0.6–2 |

| Cell voltage (V) | 1.8–2.4 | 1.8–2.2 |

| Technology status | Mature | Commercial |

| Hydrogen purity | >99.8 | 99.999 |

| Color | Process | Energy Source | CO2 Equivalent Per kg H2 | TRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray | SMR, POX, ATR, and Coal Gasification | Fossil fuel (Natural gas and coal) | 7.5–13 (SMR) [50,57] | 9 [50] |

| Blue | SMR (or other gray hydrogen production methods) and CCS or CCUS | Fossil fuel (Natural gas and coal) | 0.8–4.8 (95% capture) [50] | 7–8 [78] |

| Green | Water electrolysis (AWE, PEMWE, etc.) | Renewable Energy (Wind, solar, hydroelectric, etc.) | Nearly 0 [21] | 7–9 [79] |

| Item | Hydrogen | Ammonia | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| WtW emission | 120–155 (gray) | 86–172 (gray) | g CO2eq/MJ |

| Volumetric energy density | 7.6–8.5 at −253 °C (Liquefied) | 11.7 at −33 °C (Liquefied) | MJ/L |

| Utilization pathway |

|

| [-] |

| TRL [112] | Energy Efficiency | Main Challenges | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HICE | 5–6 | 15–34 [136] |

|

| AICE | 4–5 | 22–45 [136] |

|

| PEMFC | 6–7 (with hydrogen) 4–5 (with ammonia) | 30–60 [137] |

|

| SOFC | 3–4 (with ammonia) | 25–50 [137] |

| Fuel Type | Current | 2030 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gray hydrogen | 1.00–2.00 (2024) [139] 0.80–5.70 (2024) [35] 0.67–2.00 (2023) [138] 0.90–3.20 (2023) * [140] 0.8–4.1 (2022) [141] | 0.64–2.90 [35] | 1.5–2.4 [142] |

| Blue hydrogen | 1.20–6.70 (2024) [35] 2.40 (2022) [143] 0.99–2.05 (2023) [138] 1.3–5.2 (2022) [141] | 1.3–4.9/2.5 ** [141] 1.10–4.00 [35] | 1.3–4.9/2.2 ** [141] 1.5–2.7 [142] |

| Green hydrogen | 3.50–12.00 (2024) [35] 3.00–6.00 (2024) [139] 3.00–6.55 (2022) [143] 2.28–7.39 (2023) [138] 3.00–7.40 (2023) [140] 3.60–9.50 (2023) [142] 2.70–8.80 (2021) [144] | 2.00–10.50 [35] 2.28–7.39 [138] 2.00–6.00 [144] 1.70–7.00/2.4 ** [141] | 0.7–1.3 [142] 1.50–5.00 [144] 1.40–6.00/2.0 ** [141] |

| Gray ammonia | 0.25–0.30 (2025) [145] 0.11–0.34 (2022) [146] 0.30 (2023) [96] | none | none |

| Blue ammonia | 0.39 (2023) [96] 0.24–0.47 (2022) [146] | 0.24–0.47 [146] | 0.24–0.47 [146] |

| Green ammonia | 0.46–0.90 (2025) [145] 0.41–1.24 (2024) [147] 0.70–1.02 (2023) [96] 0.70–1.40 (2022) [146] | 0.26–0.70 [147] 0.44–0.52 *** [148] 0.48–0.95 [146] | 0.20–0.48 [147] 0.59 [145] 0.31–0.61 [146] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, C.; Choi, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, M. Sustainable Maritime Decarbonization: A Review of Hydrogen and Ammonia as Future Clean Marine Energies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411364

Jin C, Choi J, Lee C, Kim M. Sustainable Maritime Decarbonization: A Review of Hydrogen and Ammonia as Future Clean Marine Energies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411364

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Chungkuk, JungHwan Choi, Changhee Lee, and MooHyun Kim. 2025. "Sustainable Maritime Decarbonization: A Review of Hydrogen and Ammonia as Future Clean Marine Energies" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411364

APA StyleJin, C., Choi, J., Lee, C., & Kim, M. (2025). Sustainable Maritime Decarbonization: A Review of Hydrogen and Ammonia as Future Clean Marine Energies. Sustainability, 17(24), 11364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411364