1. Introduction

Fossil fuels have multiple uses, including for heating, transportation, road asphalt, propane, clothing, carpets, electronics, plastic, medicines and tools. According to BP [

1], approximately 57% of global energy was sourced from oil and gas in 2018. Crude oil and natural gas (the two raw materials) are transformed into liquefied natural gas, gasoline, diesel, and a range of energy sources and petrochemical products [

2]. Historically, oil and gas companies have been implicated in serious catastrophic events [

3,

4]. All industry processes from exploration to final product consumption are associated with serious risks and potentially serious environmental damages [

2,

3,

4]. The oil and gas industry has been subject to constant criticism from environmental protection agencies, the media, communities, and other institutions and stakeholders [

3,

5] due to its environmental impacts.

During the pandemic’s peak, it was expected that post-pandemic, climate and environmental debate would not dissipate [

6]. Innovations, which have led to lower costs for wind, solar, and batteries, will continue, and decarbonization will remain an imperative for the industry [

6]. Opposing the pressure for better environmental performance (EP), the sector has been found to face increased demand for global gas, which is expected to peak in the late 2030s due to high customer demand. Despite the wave of bankruptcies and restructuring after 2014, a new wave of business and supply chain reconfiguration, technological acceleration, and customer partnerships [

6] is expected in the post-pandemic era.

In early 2025, the United States President signed an executive order declaring a national energy emergency, with a directive to roll back regulations on the oil and gas sector [

7]. The United States has been the world’s top crude oil and natural gas producer; this directive supports further drilling and production by the United States [

7]. Nevertheless, this strong government support for the sector continues to meet resistance from environmental groups (NGOs) [

7].

Resistance from environmental groups (NGOs) is based on multiple negative environmental impacts relating to fossil fuel consumption. According to IEA [

8], from 1988 to 2015, the 60 largest oil and gas companies were responsible for more than 40% of the cumulative industrial emissions worldwide, and the ten largest oil and gas companies’ contribution was around 22% of global emissions. The pandemic resulted in a major reduction in petroleum consumption (by 25%), and it was expected that post-pandemic, in the long term, there would be 30% to 40% reduction in CAPEX and R&D investments in the Oil and Gas market [

9]. Nevertheless, this outlook is expected to change. Due to increased power consumption, demand for natural gas is anticipated to rise significantly from 2024 [

8]. Nations such as China and India accounted for over 90% of the total annual increase (of one percent) in coal consumption globally in 2024 [

8]. An additional critical factor is political support for the sector, which bears a high risk of a lack of progress relating to the sector’s environmental performance.

In the recent past, there has been an increasing call from stakeholders, including NGOs, for policymakers to formulate judicial regulatory frameworks for oil and gas industry firms, to adopt environmental management systems (EMS) and to make their operations more environmentally friendly [

10]. Various stakeholders continue to exert pressure for better environmental performance (EP) from oil and gas companies, including consumers, NGOs, the public [

11], shareholders [

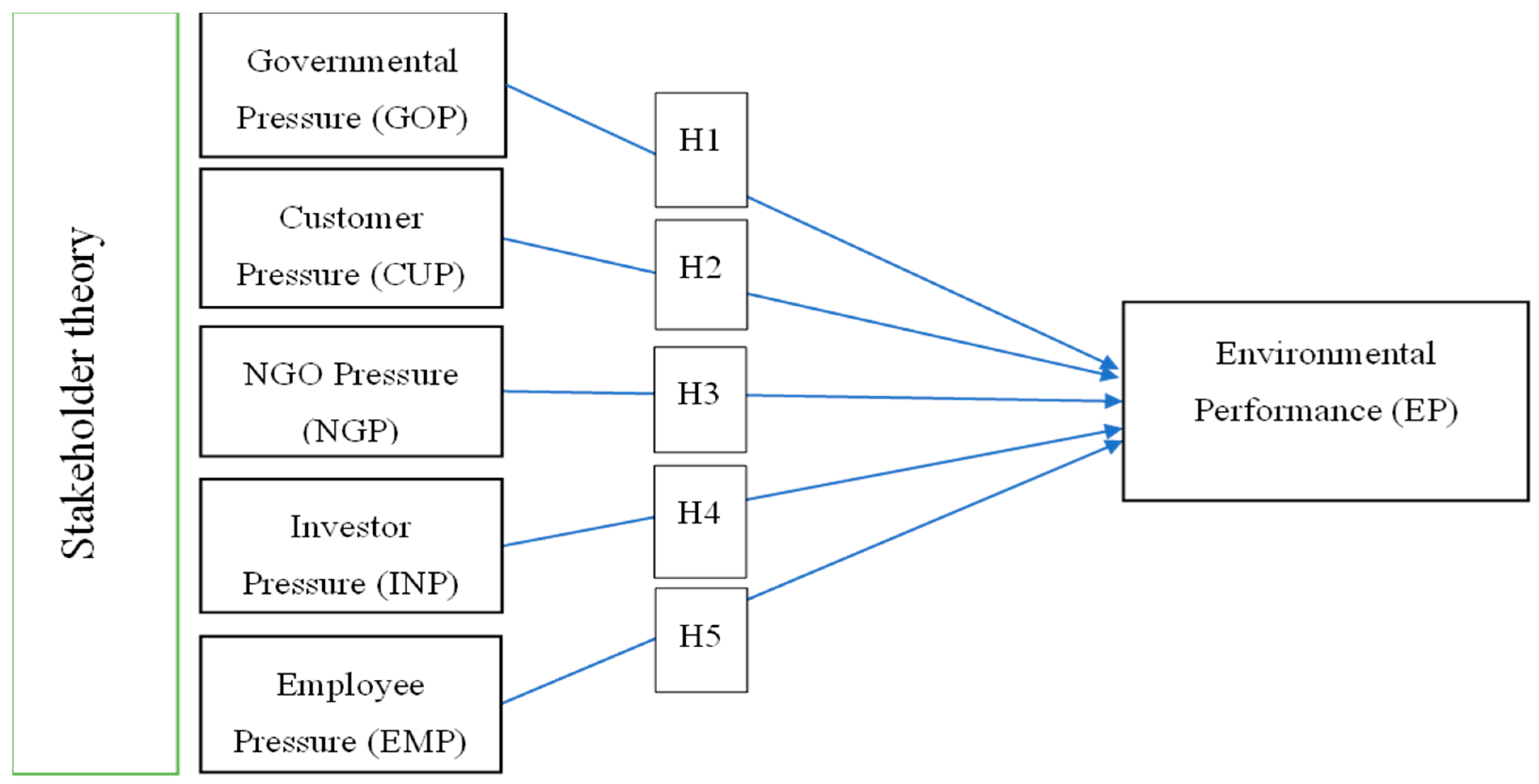

11], and, to a lesser degree, employees. We aim to address types of stakeholder pressures/influences, considering that various stakeholder pressures/influences are applied for and against the oil and gas sector’s environmental performance. Our research questions based on this aim are: Which of the stakeholder pressures exert a significant influence on oil and gas companies regarding their EP (or lack of it)? And what are the potential implications of conflicting stakeholder pressures/influences on the oil and gas sector’s environmental performance? By providing our analysis of contradictory stakeholder pressures/influences, our article adds to the literature by shedding light on the complicated current state of stakeholder influence on the oil and gas sector. Since various stakeholder influences are opposing and not uniform in one direction (i.e., to improve environmental performance), our key finding highlights an uncertain path for the oil and gas sector regarding its environmental performance.

Our findings support a high risk of business as usual for the sector, continued greenwashing, while sustained global environmental damage from fossil fuel consumption continues to occur in the long run. Dominant governments, such as the United States, have a strong tendency to exacerbate oil and gas sector related climate risks. Our contribution to stakeholder theory, as contradictory and volatile significant stakeholder influence, serves as a novel contribution to relevant literature.

The article is organized as follows: in the next section, we review prior literature, with a general focus on EP, followed by a specific focus on the oil and gas industry. We also expand on our contribution to existing literature in this section. A coverage of stakeholder theory, methodology, findings, discussion and conclusion follows this section.

2. Literature Review

EP has three elements: strategy, implementation, and disclosures [

12]. EP is a precursor to environmental disclosures [

13]. EP encompasses the measurement of the level of pollution created by a business and its hazardous emissions [

12,

14]. Indicators of EP include reduced greenhouse gas emissions, energy efficiency, water efficiency, recycling, and resource consumption [

13,

15,

16,

17].

Numerous studies have employed a survey-based method to assess EP and environmental practices [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Key elements employed included reducing environmental accidents, implementing environmental improvements, promoting recycling, enhancing stakeholder perceptions, conducting independent audits, minimizing waste, reducing resource consumption, and achieving cost savings.

Researchers have investigated various implementations of practice, management projects, and performance, including those of environmentally sensitive industries (for example, the mining, oil, and chemical industries), which can be highly damaging to natural habitats [

22,

23].

There are multiple forms of pressure exerted on companies regarding their environmental performance. One potential form of pressure is international institutional pressure [

21]. Another pressure comes from customers who can significantly influence green supply chain management [

24]. This is referred to as normative pressure, which typically originates from suppliers, customers, the media, and other societal groups [

25,

26]. Pressure from media and financial investors is positively associated with carbon management efficiency [

27].

2.1. Oil and Gas Sector Environmental Performance Overview

The oil and gas sector has been facing increased pressure regarding its environmental performance [

23]. According to Simpa et al. [

28], oil and gas companies have made significant strides towards environmental stewardship in recent years, mainly due to regulatory requirements, corporate initiatives, and stakeholder pressure. Key areas of improvement have included reducing greenhouse gas emissions related to processes, implementing carbon capture and storage technologies, investing in renewable energy sources, implementing energy efficiency measures, promoting more responsible water consumption, and implementing biodiversity conservation initiatives [

28]. Nevertheless, environmental stewardship performance of the oil and gas sector remains poor.

The sector still faces serious environmental challenges, including environmental risks associated with fossil fuel extraction and transportation [

29]. Another risk relates to stranded assets resulting from decarbonization efforts, which can nonetheless cause significant environmental damages [

30]. The most prominent risk is the lack of uniform environmental standards and regulations across jurisdictions, combined with inadequate implementation due to corruption and weak governance, which creates inconsistencies in environmental performance (EP) and accountability [

28,

31] for the sector. United States currently presents a strong government support for the sector and its profitability, with absolute disregard for its environmental impacts.

2.2. Stakeholder Pressure and Environmental Performance

Stakeholder theory posits that firms must meet the demands of their stakeholders to ensure their continued existence [

32,

33]. Thus, stakeholder pressure can influence the procedures and practices of an organisation either directly or indirectly. Environmental concerns from stakeholders have necessitated greater responsibility from businesses towards the environment [

34,

35,

36]. Government pressure, through enforced legislation and regulations, is one of the most apparent pressures that may influence a company to adopt responsible environmental practices [

37]. He et al. [

35] found that both external pressure (government pressure) and internal pressure (including pressure from management and employees) have a significant positive impact on corporate environmental behavior. The parent company (an internal stakeholder), the government, NGOs, and the media (external stakeholders) all wield significant positive influence over the environmentally responsible management of a multinational enterprise’s subsidiaries [

38]. External and internal stakeholder pressure from shareholders, marketing departments, media, and communities has influenced environmental remediation carried out by manufacturing companies in the UK [

19]. Foreign partner’s auditing pressure and NGO pressure have also been considered as main factors affecting a company’s sustainability practices [

39].

Nevertheless, it is important to note that stakeholder pressure for better environmental performance is not a straightforward implementation. Political factors play a significant role in obstructing, hindering, or reversing the environmental performance and related accountabilities of companies. Thus, although a hypothesis may suggest a positive impact of a factor on environmental performance, in the real world, these pressures or impacts encompass variability, fluidity or reversibility, which are not captured in stakeholder theory, in its fundamental form.

Further expanding on the point of fluidity/volatility, we would like to highlight (and thus add to stakeholder theory), our related conceptualization that stakeholder pressure is not a constant. It can change, also in its direction, in some instances, quite dramatically. We provide the example of U.S government pressure, which has taken a 360 degrees turn in this respect. This dramatic shift from government pressure to government support has occurred abruptly for the oil and gas sector (although there were strong indicators of this occurring during the prior election campaign). In addition, the U.S. government’s current stance, demonstrated within a matter of weeks, represents a complete rapid dismissal of government effort towards tackling climate change and undertaking climate risk management.

2.3. Environmental Performance of the Oil and Gas Industry

Oil and gas companies are among the most polluting due to environmental damages from operations, emissions, and oil spills [

4,

5,

34]. Harmful operations cause upstream and downstream impacts [

17,

40]. Upstream activities encompass all processes preceding refining oil, including drilling, exploration, production, and shipping, whereas downstream activities involve refining crude oil into usable products [

40].

Catastrophic environmental oil and gas disasters, such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, have caught the attention of academics, researchers, and the public, who claim that the total cost of environmental and economic damage was approximately

$36.9 billion in 2010 [

41]. In South Louisiana, 4.9 million barrels were released into the Gulf of Mexico, marking one of the worst oil spills in U.S. history [

41]. Environmental damage of this nature has led to demands from institutions and stakeholders for improvements in oil and gas sector practices. Patterson et al. [

42] suggest that developing regulatory requirements for the sector can prevent or minimize severe environmental damage relating to upstream and downstream activities.

A controversial practice relating to upstream activities is hydraulic fracturing (fracking), which means injecting water and chemicals into oil and gas wells under high pressure for extraction, a practice with severe environmental implications [

41]. This technique has been employed since 1947 and necessitates substantial amounts of water and chemical injections [

41]. Oil and gas companies that use hydraulic fracturing in their extraction process can improve future production needs by refilling the wells using recycled wastewater rather than fresh water [

43]. Sources of fresh water are currently under great stress worldwide, and this kind of improvement will help curtail environmentally harmful activities [

43]. Hydraulic fracturing is predominantly used in the United States to produce shale gas or oil [

44].

Numerous factors have been considered when developing EP measurements employed by oil and gas companies. For instance, a framework to assess EP in the oil and gas industry, comprises of five categories: environmental management, inputs, operations, outputs, and outcomes [

45]. In another instance, EP in oil and gas companies has been measured using five indicators: greenhouse gas emissions, natural gas flaring, use of natural water, oil spills, and waste reduction [

40].

A key element utilized as a measure of EP is carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions, which are a primary cause of climate change and global warming [

46]. Oil and gas companies have attempted to develop new technologies to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. For example, ExxonMobil purports that it has developed new processes to reduce CO

2 emissions associated with its gas production at the LaBarge Field in Wyoming, USA [

47]. Due to strong political influence of the oil and gas sector, multiple instances of green washing from the sector remain. Please see Scanlan’s analysis of manipulations to downplay environmental risks and misleading positive representations of hydraulic fracturing by oil and gas companies [

48]. Similar findings of green washing by oil and gas companies have been presented by Jamil et al. [

49], and Cherry and Sneirson [

50]. Political clout and leveraging of political ties by oil and gas companies have been discussed by different authors [

51], also in the United States context [

52].

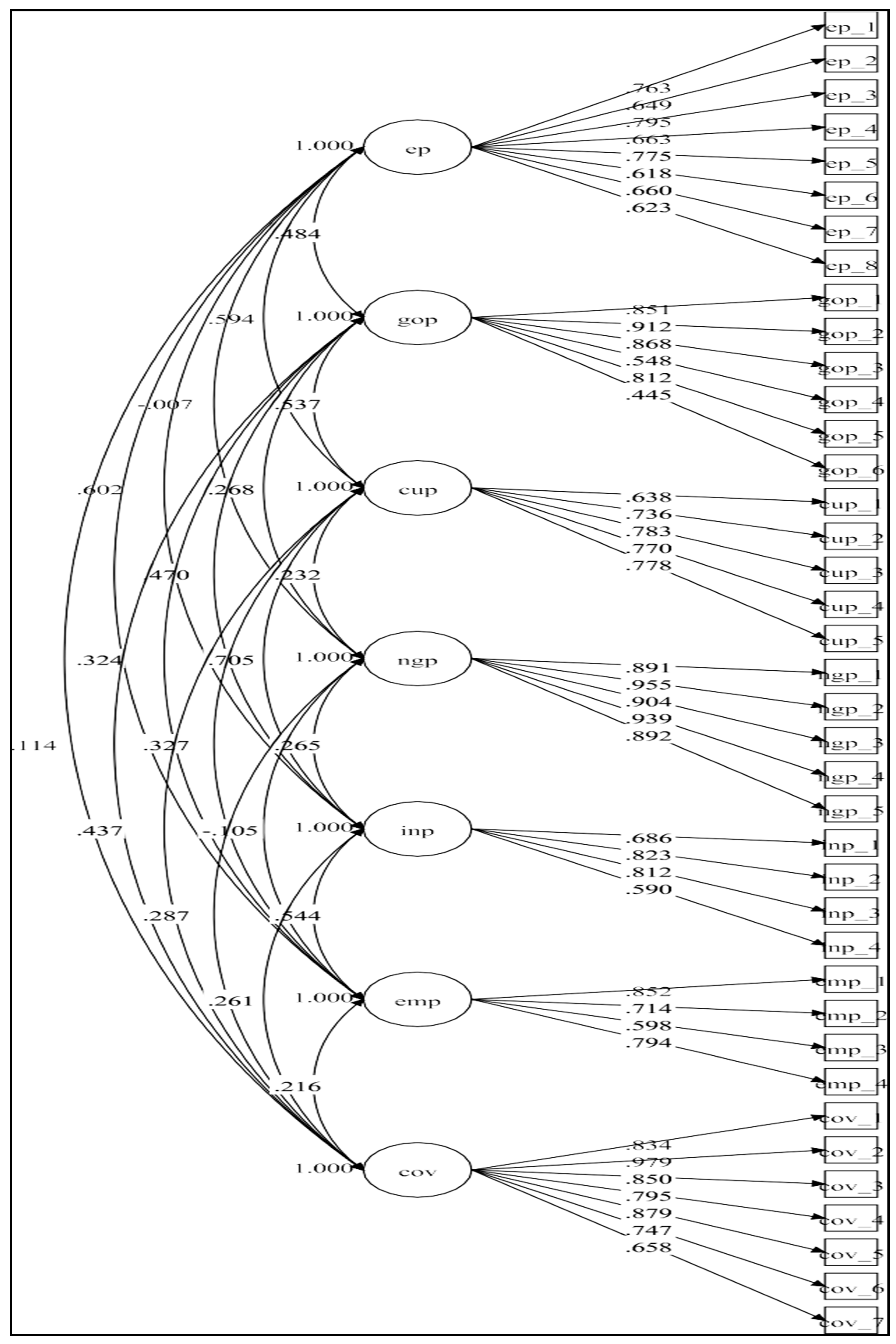

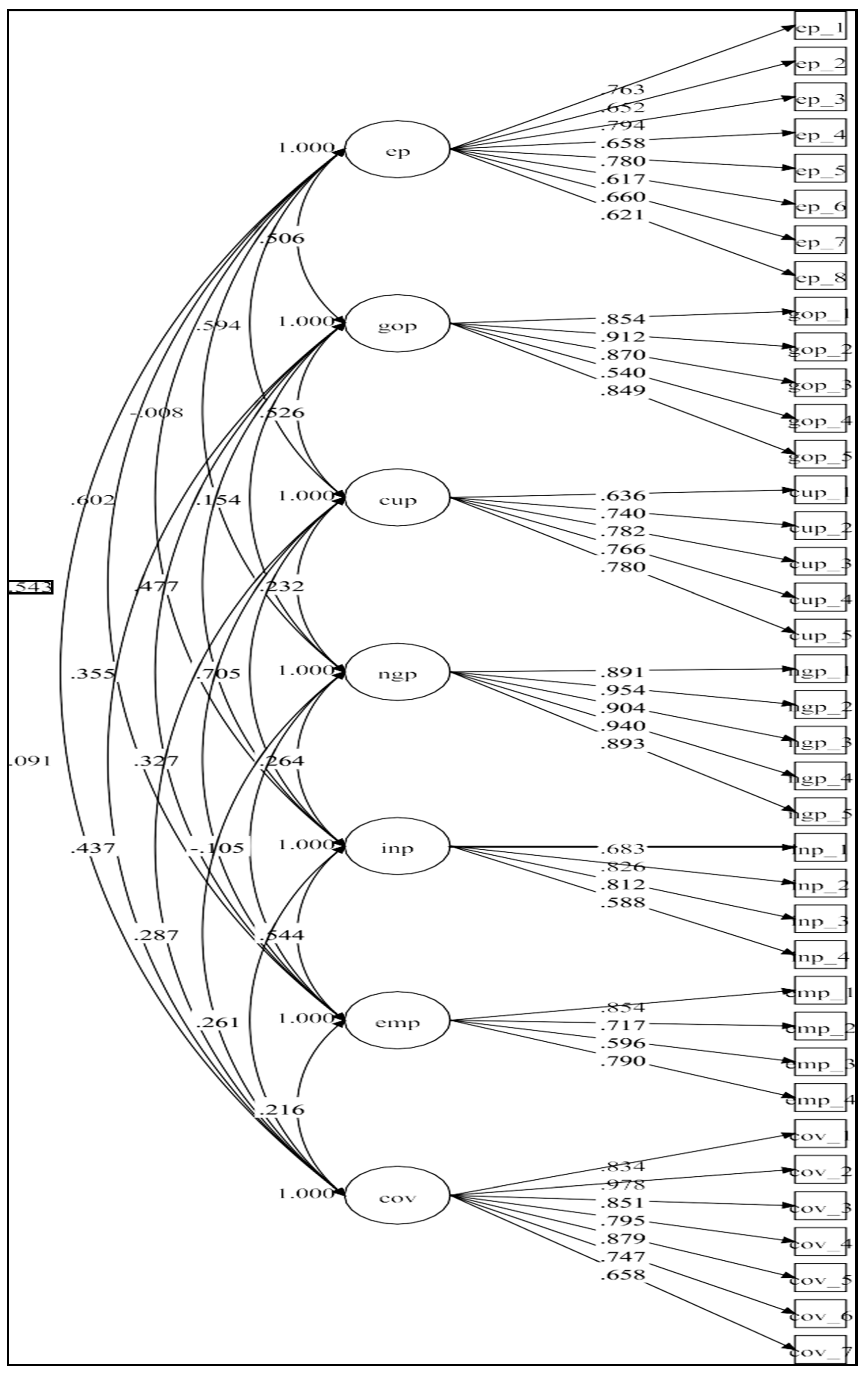

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The study finds that governmental pressure has a significant impact on the EP of oil and gas companies. This result is confirmed by the findings of [

26,

35,

87]. Companies tend to unconditionally comply with rules and regulations imposed by governments to avoid facing punishment/penalties. More recently, substantial steps towards making sustainability (including climate-related risks and opportunities) mandatory through legislation had been undertaken, prior to 2025. For example, the European Sustainability standards (ESRS) were adopted for use by companies subject to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) [

88]. Companies comply with governmental regulations and policies to gain benefits such as access to resources and tax deductions [

26,

52]. For the oil and gas sector, despite international calls, such as by the United Nations, to reduce subsidies for the oil and gas sector, the opposite has been occurring. For example, in Australia, subsidies for producers and users of fossil fuels have increased by 31% in 2022–2023 [

89]. Globally, in 2022, subsidies for fossil fuel consumption exceeded

$1 trillion U.S. [

8]. Further measures to support the oil and gas sector are underway in the United States.

The study finds that customer pressure has a significant positive influence on EP. This finding is consistent with other studies [

26,

35,

87]. However, this finding is inconsistent with the results of Cherry and Sneirson [

50] who found no significant impact of customer pressure on EP. Customers can pressure companies to improve their environmental practices [

90]. Reputational risk pressure can play an important role to influence minimization of the risk of harm and to promote redress in case of caused harm [

11].

The study finds that NGO pressure has a nonsignificant impact on the EP of oil and gas companies. This result is in coherence with [

35,

69,

91]. However, these findings are inconsistent with the results presented by [

53,

92]. Their findings supported the hypothesis that NGOs would have a significant impact on EP. NGOs undertake indirect approaches to influence a firm’s activities [

19,

92]. NGOs, as external stakeholders, tend to rely on developing public opinion to oppose an organization’s activities [

93]. Their impact might not be directly noticeable to the decision-makers in companies. Nevertheless, NGOs might influence a company’s more influential stakeholders (such as investors) who could pressure companies to improve their EP.

Previous research has found that shareholders want more action from companies (especially in the Oil and Gas sector) to improve their environmental practices [

19,

94]. Thus, we hypothesized that investor pressure would significantly impact EP in oil and gas companies. Surprisingly, our results did not reveal a significant association between investor pressure and EP in the oil and gas industry. This finding is similar to [

95,

96]. However, this finding contradicts [

19,

26] who claim a significant positive association between investor pressure and environmental practices. In relation to high-polluting industries such as oil and gas, investors are more concerned with profitability than EP, and some shareholders might feel that environmental practices will negatively impact their financial wealth [

97].

The study finds that employee pressure has the highest positive significant impact on EP in oil and gas companies. This finding is supported by [

20,

63,

97]. However, it is inconsistent with the outcome of Studer et al. [

98], who found a weak relationship between employees and EP. In the current (political) environment, this finding might not hold.

Employees are directly involved in the firm’s activities, including financial, environmental, and social practices. Employees are critical internal stakeholders who can significantly contribute to a firm’s success and are considered influential [

93,

99,

100]. Nevertheless, corporate power may significantly dilute any employee’s say in relation to corporate activities and environmental impacts.

In relation to political influence, a major recent occurrence is the staunch support for the oil and gas sector by the United States government. There is a rapid reversal of environmental accountability (in the form of legislative measures) and thus a complete reversal of government pressure for better EP of United States’ Oil and Gas companies. Currently, a key aim is for the United States to be the major exporter of natural gas to Europe, thus weakening (and perhaps removing Russia) from the EU market. Not only that, strong ties between the U.S. government and the oil and gas sector are evident in administrative roles, including senior positions, being assigned to individuals who have worked for oil and gas companies [

101,

102]. These individuals are responsible for influencing U.S. environmental, climate and energy policies [

101].

More recently, Trump has urged the World Bank to reverse the 2019 restrictions on financing of new fossil fuel projects [

103]. Trump’s billions of dollars’ worth of handouts to the oil and gas sector are a form of policy reward for the sector’s

$450 million contribution to Trump’s election [

104]. These handouts comprise of increased depreciations (worth billions), tax exemptions, delays in fees, reduced royalties and waiver of climate related liabilities, amongst other handouts [

104]. These current U.S. government practices are examples of reversal of government pressure, and greater corporate power/influence resulting in, in this case a win and gain situation for the U.S. oil and gas sector.

There has been conflicting pressure from governments, civil society, and international bodies on the oil and gas sector to improve its EP [

28]. Governments (and legislators) seem to be demonstrating increased leniency towards the sector and NGO, and customer pressure seems to be weakening.

Our results suggest the need for differential strategies to effect meaningful changes in the oil and gas sector, such as implementing legislative measures to enhance the EP of oil and gas companies. Recent developments in the legislative space have included the implementation of ESG criteria, which require oil and gas companies to consider social and environmental factors in their decision-making in Europe [

97]. Nevertheless, requirements by the EU are becoming more relaxed.

Regulations and policies aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote cleaner energy technologies, prevent accidents, manage risks, and ensure the responsible extraction of fossil fuels [

105]. At the same time, there seem to be complexities around government pressure on oil and gas companies. For example, consider this quote from Environment Victoria [

106]: “Amendments to the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Legislation Amendment (Safety and Other Measures) Bill 2024 would effectively grant the offshore oil and gas industry a free pass from national environmental laws.” The implication is that of corporate lobbying, reverse pressure on governments from companies (corporate power), in this case, to relax legislative requirements for environmental protection.

In relation to our findings that government pressure has a significant influence on corporate EP, U.S represents a potential case of reverse causality, which adds further complexity to the understanding of government pressure. It also indicates the exercise of corporate power [

107] over governments. The oil and gas sector has immense power in this regard. Corporate influence by the U.S. oil and gas sector, has resulted in current complete disregard for environment and climate change associated risks, by the U.S. government. The current situation is a quintessential example of reverse pressure on the U.S. government. Implications are dire in relation to the environmental performance of U.S. oil and gas companies. Resulting risk of irreversible environmental damage, not restricted to the United States, but in multiple parts of the world, from U.S. oil and gas companies, is extremely high.

Corporate power, as in this case, tends to weaken other stakeholders’ pressure for better corporate environmental performance, from a highly environmentally sensitive industry, such as the oil and gas sector. Such situations thus lead towards sole dominance of one stakeholder (such as government) and cause a chain reaction, not just restricted to one region. In the context under consideration, relaxing of environmental protection policies in other jurisdictions (such as currently in European Union) has commenced. It is possible that EU is following in the steps of U.S., not in entirety, definitely to a degree, where government pressure is facing counter industry lobbying from the oil and gas sector.

Although mandatory reporting on EP is necessary to demonstrate accountability in the oil and gas sector, governments’ current requirements for this form of accountability appear to be reversing, rapidly in some instances. Further research is required from the angles of EP, environmental reporting and accountability (including from policy and implementation perspectives) and strategizing for more effective NGO pressure for better corporate EP.