1. Introduction

Ports are critical nodes in global supply chains [

1] and are of significant importance to global trade and economic development. They are key infrastructures for the ‘Blue Economy’ [

2], along with maritime transport, fisheries, offshore energy development, sea tourism, and many economic activities in coastal zones. Over 80–90% of world trade volume is carried by sea (and more than 70% in terms of value) [

3]. With 4% annual growth in maritime trade over the coming five years [

4], ports are crucial hubs of strategic importance to future trade and development prospects. However, their location in the coastal zone (low coasts and/or deltaic areas, rivers or lakes) makes them particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts. They are highly exposed to a variety of climate change hazards, i.e., sea level rise and extreme weather conditions, which are projected to become more frequent and severe [

5,

6]. These climate change pressures will have a profound impact on port infrastructures and operations and will pose a threat to coastal populations and to economic prospects at regional and even national levels, through port operation delays, supply chain disruptions, or damages [

7,

8,

9].

As most port infrastructures were constructed under different climate conditions, a re-examination of established practices is considered urgent [

10]. This is a challenge that—despite having been highlighted in many studies worldwide [

11,

12,

13] as being expected to determine the future vulnerability of ports [

14]—only few port authorities and operators have addressed. Enhancing port resilience to climate change constitutes both a strategic economic imperative and a fundamental component of sustainable development [

15].

Towards this goal, the adoption of the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate change in 2015 [

16] marked a significant step in strengthening global commitments to both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation refers to “

human intervention to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases” [

17], i.e., actions aiming to limit or prevent climate change by reducing the emission of greenhouse gases (e.g., from energy, transport, and industry) or by increasing carbon absorption (e.g., through forests, soils, or technologies like carbon capture and storage). Adaptation is defined as “

the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects” [

17], i.e., making changes in social, economic, and environmental practices to reduce vulnerability/increase adaptive capacity to cope with the impacts of climate change, such as rising sea levels, extreme weather, or shifts in ecosystems. Notably, climate change adaptation strategies are assumed to be more effective than mitigation approaches, as these can focus on local–regional spatial and short–medium-sized scales; moreover, such strategies can enable national–regional cooperation and can be proactive if they are based on climate impact projections [

18]. Port adaptation planning involves the following measures: (a) climate risks assessments; (b) the evaluation of the expected impact on port infrastructures, superstructures and operations; (c) the development of necessary proactive processes and measures (i.e., technical, institutional, education); (d) the application of these measures. Enhancing adaptive capacity-building is vital to protecting these critical infrastructures and ensuring their long-term operational sustainability [

19].

Based on the above, the present paper focus on Greece’s port system and, through some case studies, aims to set the scene regarding the potential climate change impacts on Greek ports, the existing policies and strategies vis à vis tackling these impacts, and potential steps towards a more comprehensive framework for climate change adaptation through relevant state policies and port strategies. Specifically, it seeks to address the following research questions:

- ○

How do stakeholders in Greek ports perceive the risks and impacts of climate change on port operations and infrastructures?

- ○

What is the current level of preparedness and adaptive capacity of Greek ports to address climate-related challenges?

- ○

What institutional, governance, and policy gaps jeopardize the effective implementation of climate adaptation strategies in Greek ports?

- ○

How is climate change prioritized in comparison to other environmental challenges within Greek port authorities?

- ○

How do stakeholder roles and governance structures influence decision making and the integration of climate adaptation measures in port management?

The paper contributes to discussions regarding the impacts of climate change on ports, providing insights from an insular country. Also, it sheds light on port stakeholders’ perceptions of climate change as an environmental challenge for Greek ports and the existing barriers towards a more comprehensive approach to port climate adaptation and mitigation measures. Moreover, the research results can be used for the formation of relevant state policies and port authority strategies aiming to tackle CC impacts on port infrastructures, superstructures, and operations. This is important, especially for Greek ports; many Greek ports facilitate the activities of island communities, serving as the only connections they have to the mainland, and thus playing a crucial role in maintaining social cohesion. In addition, there is a governmental strategy for supporting the attraction of private operators to Greek ports, mainly through the sale of the majority of shares of Greek port authorities. In some cases, these privatizations are accompanied by compulsory investments. As a result, CC adaptation and/or mitigation investments could be considered under this privatization scheme.

To address these questions, the paper is organized as follows: The next section presents a comprehensive literature review. This is followed by the Methodology Section, which outlines the research design and analytical methods used.

Section 4 presents the outputs of the findings of both the quantitative and qualitative analyses, identifying perceptions, priorities, and institutional preparedness. The Discussion Section interprets these findings in light of broader environmental, financial, and policy challenges; finally, the Conclusion synthesizes the main insights derived from this study.

2. Literature Review

Climate change adaptation in ports is increasingly being framed as an essential dimension of sustainability rather than a standalone challenge. Looking beyond 2050, all ports will need to adapt to climate change challenges, and this will require additional funding. The potential adverse impacts of climate change may be wide-ranging, but they vary considerably by physical setting, climate forcing, mode of transport, and other factors. In the light of recent projections and given the potential for a broad range of impacts due to climate change, all stakeholders involved in port planning, development, and operations will need to consider climate change implications in their decision-making processes. Contemporary port governance recognizes that addressing climate risks such as rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and temperature variability can prevent port damage (e.g., port defense overtopping, pier and quay inundation) and/or significant disruptions in port related operations (e.g., restrict access, ship maneuvering and birthing) [

13,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Enhancing the adaptive capacity of ports is fundamental in achieving sustainable development, ensuring that economic growth, environmental protection, and social well-being are jointly advanced, in addition to amplifying overall returns on investment by preventing losses and generating substantial long-term benefits [

24]. This approach encompasses the development of a resilient infrastructure that minimizes environmental impacts, supports the development of green building standards [

25,

26,

27], and aids the systematic reduction in carbon footprints through energy efficiency and renewable energy adoption [

28,

29,

30]. By embedding climate resilience within the sustainability agenda, ports can not only safeguard their operational continuity but can also become aligned with global commitments to sustainable development and decarbonization, reinforcing their role as sustainable and responsible nodes in the maritime supply chain [

31,

32,

33].

Ports operate within complex socio-technical systems where multiple stakeholders (e.g., port authorities, local communities, state, shipping companies) share overlapping responsibilities in port governance [

34] and climate adaptation management. Collaboration among stakeholders constitutes a recurrent theme in the literature, focusing on the need for stakeholder participation in vulnerability assessment processes, the value of critical data and information exchange, and cooperative engagement [

7,

35]. The literature underscores that the success of resilience strategies largely depends on the extent to which the actors participate in systematic and well-coordinated collaboration, supported by transparent governance and shared decision-making protocols [

36]. However, empirical evidence reveals persistent challenges: fragmented communication channels, unclear role allocation, and tensions between centralized and decentralized governance modes. Centralization offers unified responses but risks rigidity, whereas decentralization enhances adaptability yet complicates coordination [

37]. Conflicts often arise from the contradictory character of economic growth and environmental protection, while synergies emerge in initiatives that align operational efficiency with sustainability goals as in the case of port greening programs and renewable energy adoption.

On a research level, studies focus on the assessment of the perceived risks [

22,

38], exposure [

39], and vulnerability indicators [

13,

40]. Other studies estimate the regional economic impacts following the consequences of port disruptions due to extreme wind events [

41], overtopping [

42], sea level rise [

23,

43], or tropical cyclones [

44]. Recently introduced tools propose the integration of both technical and governance dimensions to assess ports’ resilience to climate hazards [

45]. Key to increasing climatic port resilience is the active engagement of port stakeholders, including among others port authorities, local governments, private operators, and community representatives. Thus, increasing awareness toward climate change will enable all relevant stakeholders to better understand the potential consequences of climate change on port infrastructure, as well as the impacts in the broader socioeconomic context. Port authorities and governments need to re-evaluate port planning and operational strategies, ensuring they are robust, flexible, and capable of withstanding evolving environmental challenges [

31].

Within a broader international framework, growing awareness of climate risks in the maritime sector has prompted targeted initiatives aiming to enhance port resilience. Notable examples include the World Ports Climate Declaration and the World Ports Climate Initiative, which underscore the sector’s recognition of the need for coordinated adaptation efforts. In addition, the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (adopted in September 2015), a “plan of action” with 17 “integrated and invisible, global in nature and universally applicable” Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), accounts for the port adaptation strategy in SDGs 13, 9, 14, and 15. These state the following intentions, respectively: to take action to combat climate change and its impacts; to build resilient infrastructures; to conserve and sustainably use the ocean; and to build the resilience of poor populations and those in vulnerable situations, reducing their exposure and vulnerability to climate- related extreme events [

46].

In the European Union, binding legal frameworks and accompanying technical guidance have been established to ensure that new infrastructure developments, including ports, are designed to withstand current and future climate risks. Their application aims to strengthen the adaptive capacity and preparedness of ports and systematically integrate climate resilience considerations into infrastructure planning and implementation [

47]. Additionally, climate change is assumed as the top concern in the environmental priorities of the European port industry [

48]. The European Climate Law [

2], mandates resilience-building measures and regular progress reviews (Art. 5), whilst the EU Climate Adaptation Strategy [

49] reinforces this objective by setting the vision of a climate-resilient EU by 2050. For ports, these frameworks translate into operational mandates through sectoral legislation, forcing port authorities and operators to integrate climate risk considerations into port planning, design, and maintenance. Such integration is essential for sustaining port operability, ensuring safe berthing, and maintaining supply chain continuity under intensifying climatic hazards [

15].

Several EU-level instruments have direct implications for Greek ports, imposing obligations that extend beyond environmental stewardship to systemic resilience. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive [

50] requires that port projects assess vulnerabilities to climate hazards such as sea-level rise and flooding, mandating consideration of both the direct and indirect impacts on infrastructure, human health, and ecosystems (Art. 3; Annex III 1(f)). Similarly, the Floods Directive [

51] compels Member States to identify flood-prone areas and implement coordinated risk-reduction measures, a critical safeguard for low-lying port facilities. In the transport domain, revisions to the TEN-T Regulation and adoption of the Directive on the Resilience of Critical Entities [

52] establish obligations for climate-proofing and disaster risk reduction across key nodes of transport networks, explicitly including ports. These legal frameworks position climate adaptation as a regulatory imperative rather than a discretionary practice, embedding resilience obligations within the operational and financial planning of port authorities.

Despite robust EU-level frameworks, implementation at the national and local scales remains uneven, revealing persistent governance gaps. This can be attributed to several reasons, including delays in transposing EU directives into national law, the absence of technical design standards for sea-level rise in port planning, and insufficient localized risk assessments for extreme weather and flooding. Without proactive measures to embed climate resilience into legal and governance systems, ports risk operational disruptions with cascading impacts on trade, energy security, and coastal communities [

15].

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Structured Questionnaire

4.1.1. Respondents’ Profiles

The majority of respondents are aged between 46–50 years (27.7%) and over 55 years (26.2%). Regarding education, 41.5% hold higher education degrees, and 40% have postgraduate qualifications (

Table 2). Most respondents (38.5%) have worked for their organization for less than 5 years, with 20% having over 20 years of service. Approximately 24.6% were employed for 16–20 years, while smaller percentages were noted for those with 6–10 or 11–15 years of employment. A significant portion of respondents (64.6%) work for municipal port funds and the rest (35.4%) are employed by port authorities. Additionally, 76.9% are part of public port entities, whilst 23.1% work for private port entities. Among them, 21.5% are members of port associations, 57.1% of which are members of the European Sea Ports Organization (ESPO), 21.4% belong to the Hellenic Ports Association (ELIME), 14.3% are part of both, and 7.1% are members of ESPO and MEDCRUISE (the Association of Mediterranean Cruise Ports).

4.1.2. Perception of Climate Change

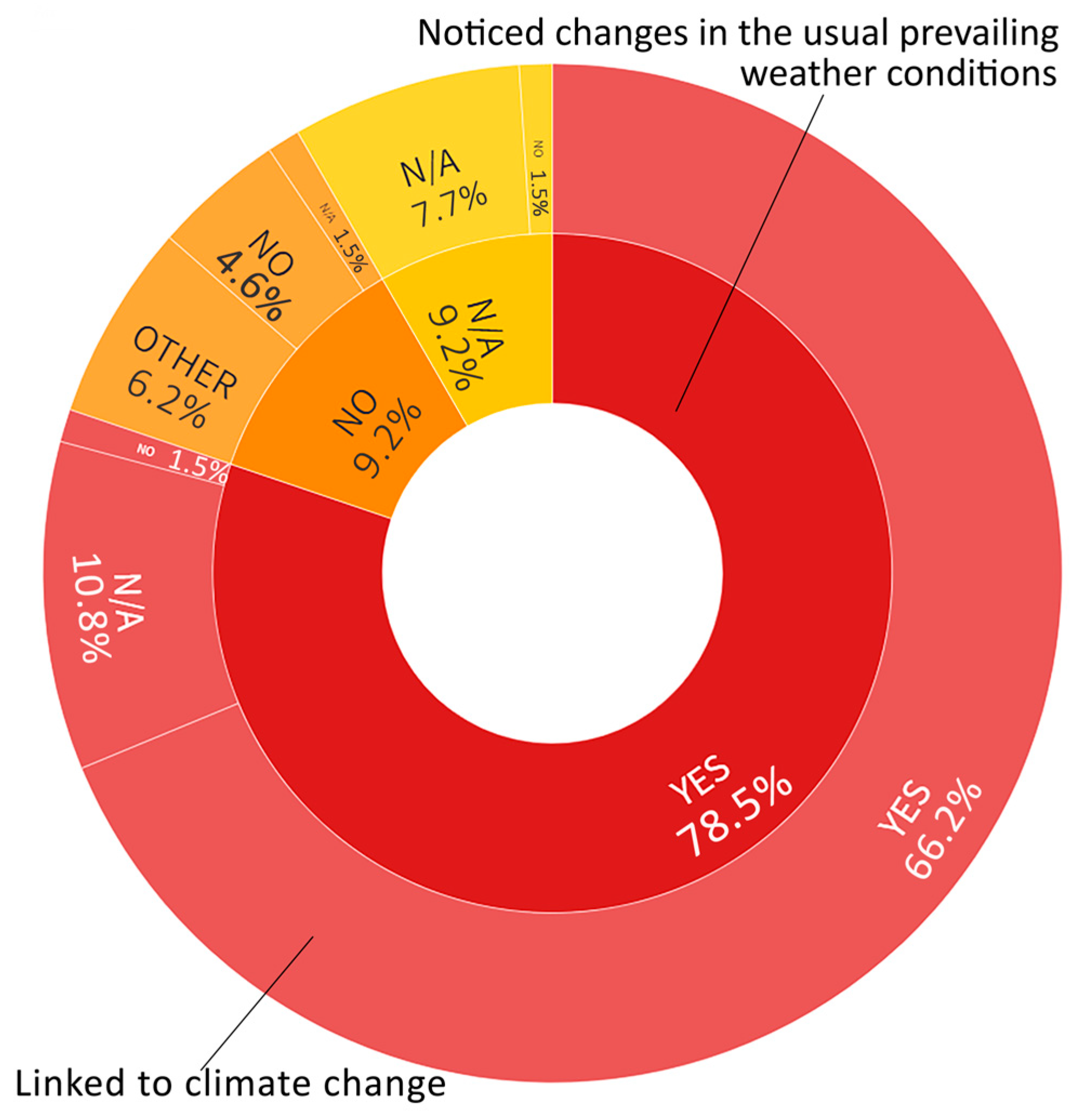

Based on participants’ responses regarding changes in weather conditions and the climate, the survey revealed that the majority (78.5%) acknowledged significant shifts in the climate (

Figure 2). A smaller portion (12.3%) stated that they had not observed any changes, while 9.2% were unsure or preferred not to answer. Amongst participants who observed changes in weather conditions, 69.8% agreed that these were indeed connected to climate change. A minority (3.2%) disagreed with this assessment, and 27% were uncertain or could not provide an answer. Lastly, 96.9% affirmed a belief in the reality of climate change, demonstrating an overwhelming consensus that climate change is a significant and ongoing issue, highlighting the broad recognition of its importance. Only 3.1% questioned its existence.

Based on the findings, 10.8% of participants do not associate observed changes in weather conditions with climate change. A closer look at this group reveals that all participants are employed in municipal port funds, indicating that uncertainty is more prevalent in smaller-scale port environments, whilst none of these respondents are employed in larger port authorities, suggesting a better-informed status with mainstream climate science narratives.

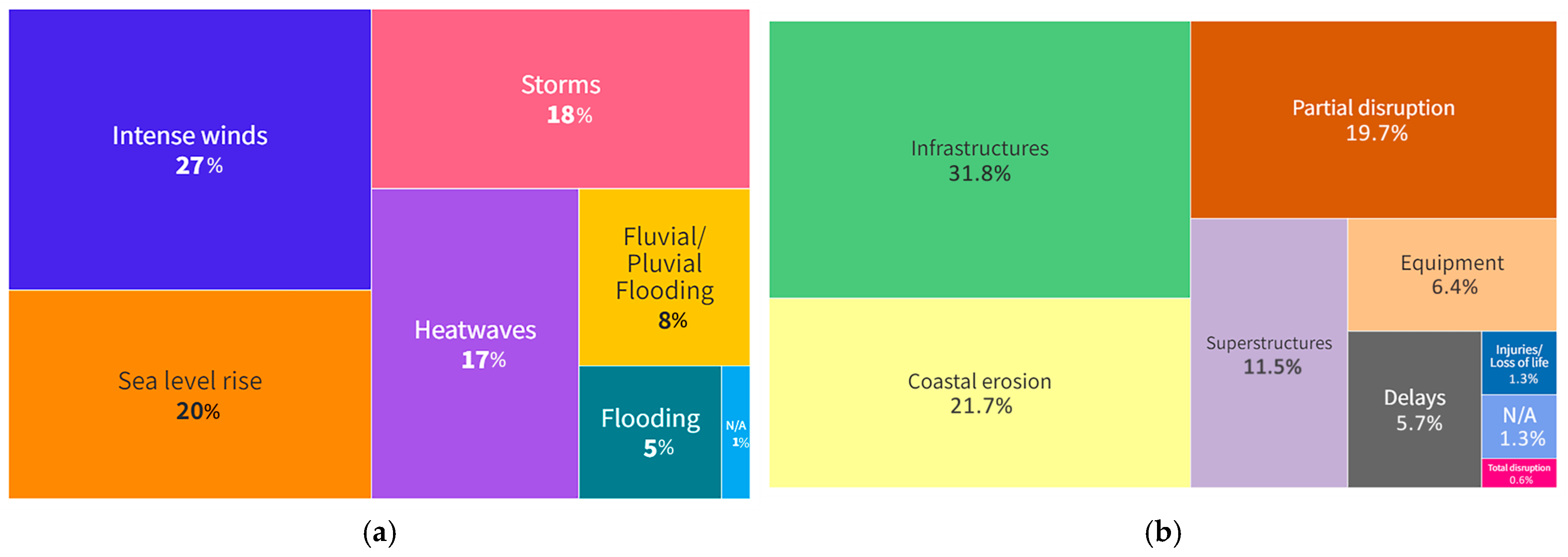

With respect to climate forcings (

Figure 3a), participants identified the increase in strong winds (27%) as the most concerning climate change effect on ports, followed by rising sea levels (20%), storms (18%), and heatwaves (17%). Fewer respondents highlighted flooding from inland sources (8%) or the sea (5%). Key concerns of the participants regarding the impact of climate change on ports included damage to infrastructure (31.8%) and coastal erosion (21.7%). Other issues included disruptions to port operations (19.7%), damage to superstructures (11.5%), and mechanical equipment failures (6.4%). None of the respondents argued that there would be no impact (

Figure 3b).

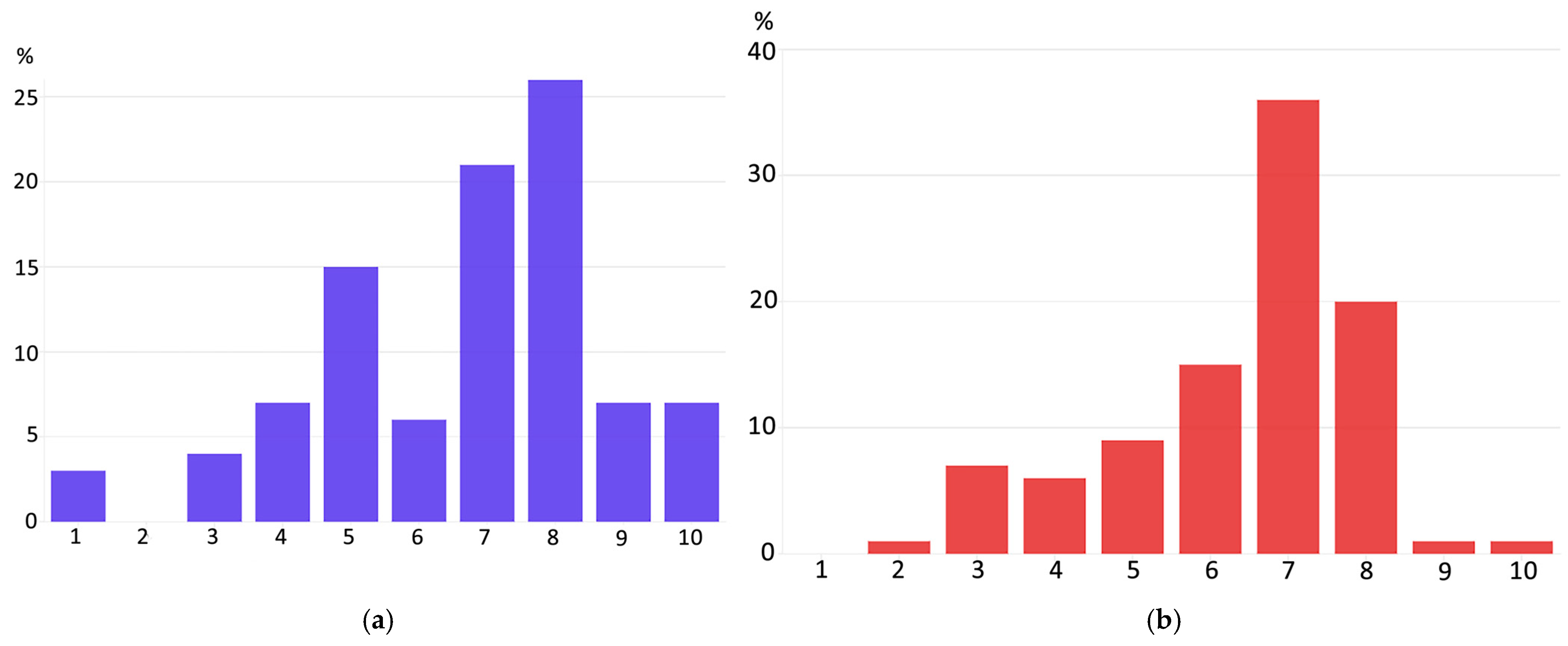

When asked to rate the potential impact of climate change on their ports, 26.2% assigned a score of 8 out of 10, indicating that the port is perceived as highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, while 21.5% gave a rating of 7, reflecting a moderate level of concern (

Figure 4a). Regarding the ability to address climate change impacts (

Figure 4b), 36.9% believed these could be moderately addressed (rated as 7 out of 10), whilst another 20% perceived a high potential to address them effectively (

Figure 4b).

Respondents were asked about their perspectives on the most appropriate solution approach for addressing climate change. Here, 58.5% favored mitigation efforts focused on reducing the causes of climate change, whilst 26.2% supported adaptation measures to help societies adjust. However, 12.3% felt climate change could not be addressed, and 15.4% were unsure (

Figure 5). Regarding fit-for-purpose investments, 78.5% of the respondents were not aware whether forthcoming port infrastructure plans account for the possible expected impacts of weather or climatic factors; 16.9% declared that adaptation measures are included, and 4.6% responded that there has not yet been any relevant work.

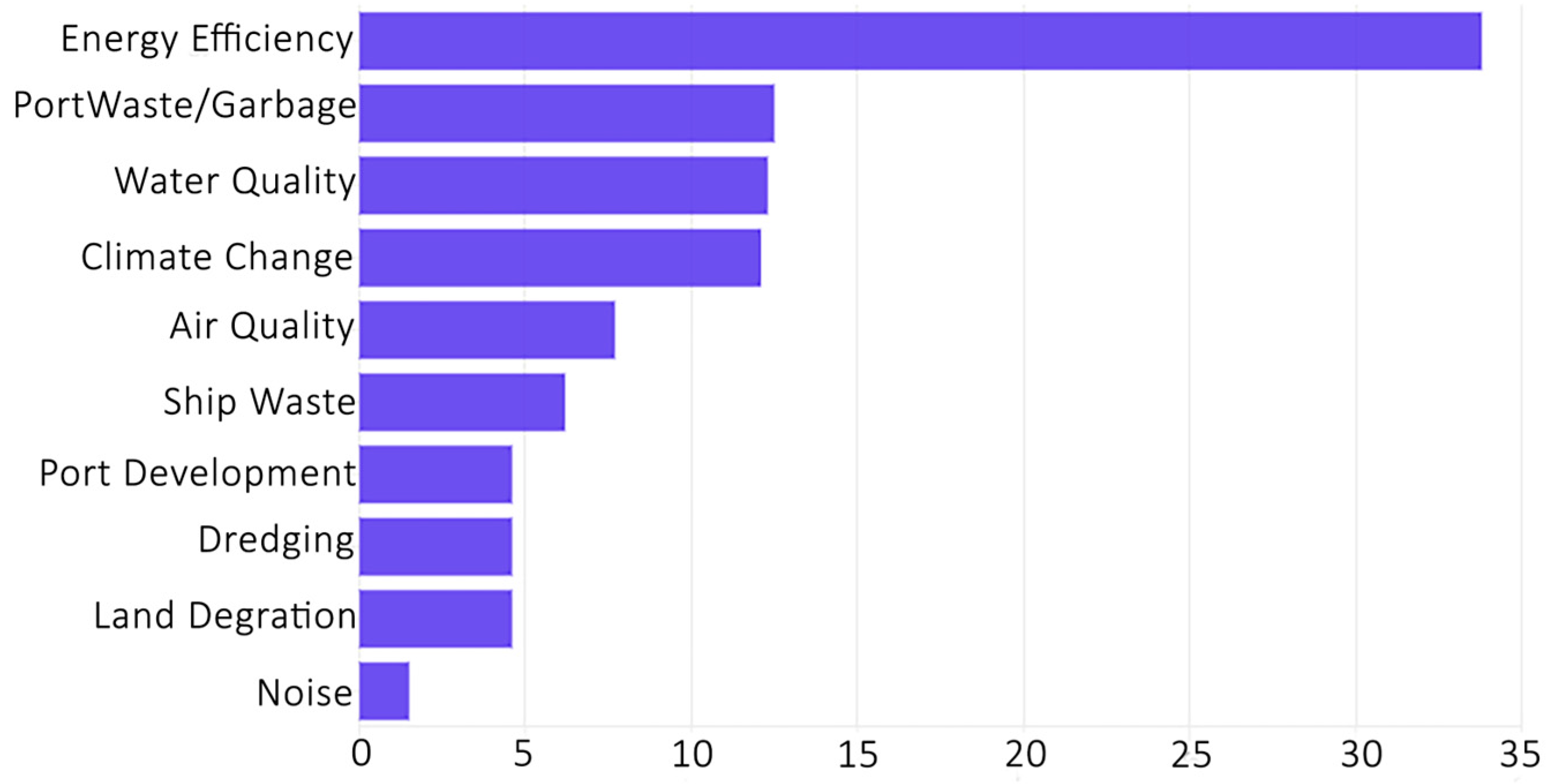

4.1.3. Analysis of Prioritization of Environmental Concerns

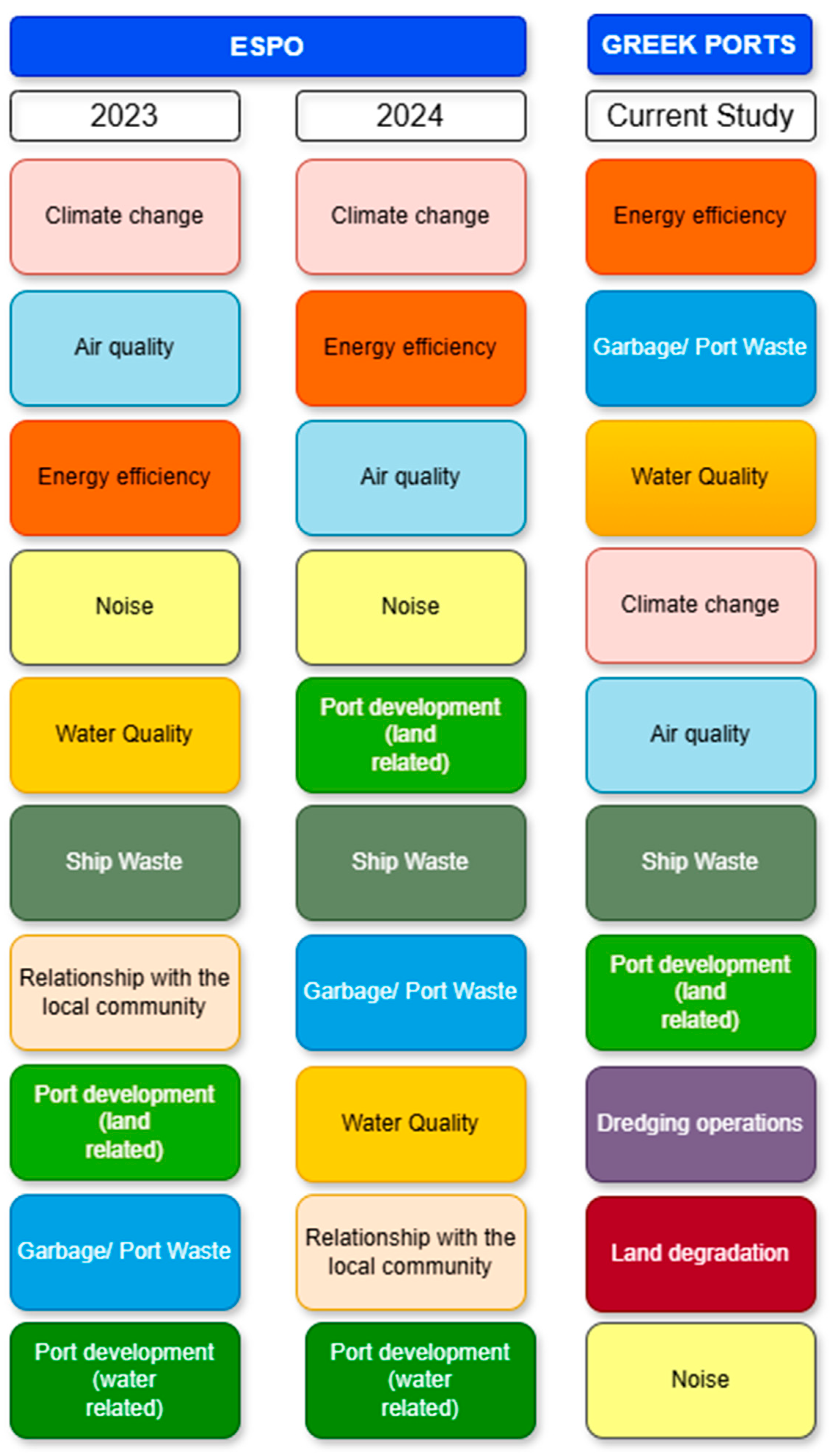

When ranking the responses to environmental concerns, energy efficiency was identified as the top priority by 24.6% of the responses, followed by port waste (12.3%), water quality, specifically pollution (12.2%), and climate change (12.1%) (see

Figure 6). Therefore, it seems that, although climate change is widely acknowledged as a serious threat, its prioritization as an environmental concern remains relatively low, ranking fourth overall— this is in contrast to the higher emphasis seen in European contexts overall, where climate change has been the port sector’s foremost environmental priority since 2022 [

48] (

Figure 7).

Amongst all environmental concerns, energy efficiency emerged as a primary concern and a top strategic priority, as evidenced by findings from both interviews and the questionnaire survey. In the port sector, improving energy efficiency has become a top priority, particularly in light of Directive 2014/94/EU on the deployment of alternative fuels infrastructures [

58]. A central requirement of this Directive is the provision of shore-side electricity, commonly referred to as “cold ironing”, to reduce emissions from vessels at berth. The directive obliges EU Member States to establish minimum infrastructure standards for alternative fuels such as electricity, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and hydrogen, through the development of national policy frameworks, technical specifications, and user information provisions (Article 1). In response, port authorities are actively implementing energy efficiency measures to comply with regulatory requirements of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, enhancing environmental performance, and supporting long-term economic resilience. These efforts support the broader climate change mitigation objectives, as they aim to lower energy consumption and minimize the environmental footprint associated with energy production and use in the port environment.

Port waste management, identified as the second-highest priority, emphasizes the need for systematic monitoring of the waste generated in ports. This aligns with the objectives of the Waste Framework Directive 2018/851/EU, which amends Directive 2008/98/EC [

59]. The directive introduces a comprehensive framework aiming to safeguard human health and the environment by minimizing waste production and its harmful effects, enhancing resource efficiency, and facilitating the transition toward a circular economy. Within the port sector, efficient handling and reduction in port-generated waste not only contributes to improved environmental outcomes but also supports compliance with regulatory standards and reinforces port commitments to sustainable development.

Water quality ranks just behind climate change as a critical environmental priority for the port sector and encompasses a range of parameters—chemical, physical, biological, and radiological—that define the condition of water bodies, including coastal and marine environments where ports are typically located. Due to their strategic location and operational footprint, ports have a significant responsibility to protect water quality and prevent marine pollution. The monitoring and management of water resources in this context are governed by the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) [

60], which aims to achieve good ecological and chemical status of inland surface waters, transitional waters, coastal waters, and groundwater and seeks to prevent and reduce pollution, promote sustainable water use, and mitigate the impacts of floods and droughts. The implementation of the Water Framework Directive introduced several provisions of direct relevance to port operations, navigation, and dredging activities, notably under Articles 16 and 4 (7), which address the regulation of priority substances and exemptions for activities with overriding public interest, respectively.

Ship-generated waste encompasses a wide range of materials, substances, and operational byproducts produced during a vessel’s normal activities. Proper management of these wastes is essential to prevent adverse impacts on the marine environment and public health. The revised Directive (EU) 2019/883 on port reception facilities [

61], which came into force in 2021, addresses this issue by aiming to reduce the discharge of ship-generated waste and cargo residues into the sea. It establishes a harmonized framework to ensure that ships deliver their waste to adequate reception facilities available in ports rather than resorting to illegal disposal at sea. The directive strengthens the obligation for waste delivery, improves enforcement mechanisms, and enhances cost-recovery systems to incentivize compliance. By mandating more effective waste handling and monitoring systems at ports, the directive plays a key role in supporting the broader goals of marine environmental protection under international conventions, such as MARPOL.

4.1.4. Stakeholders’ Engagement and Policy Making

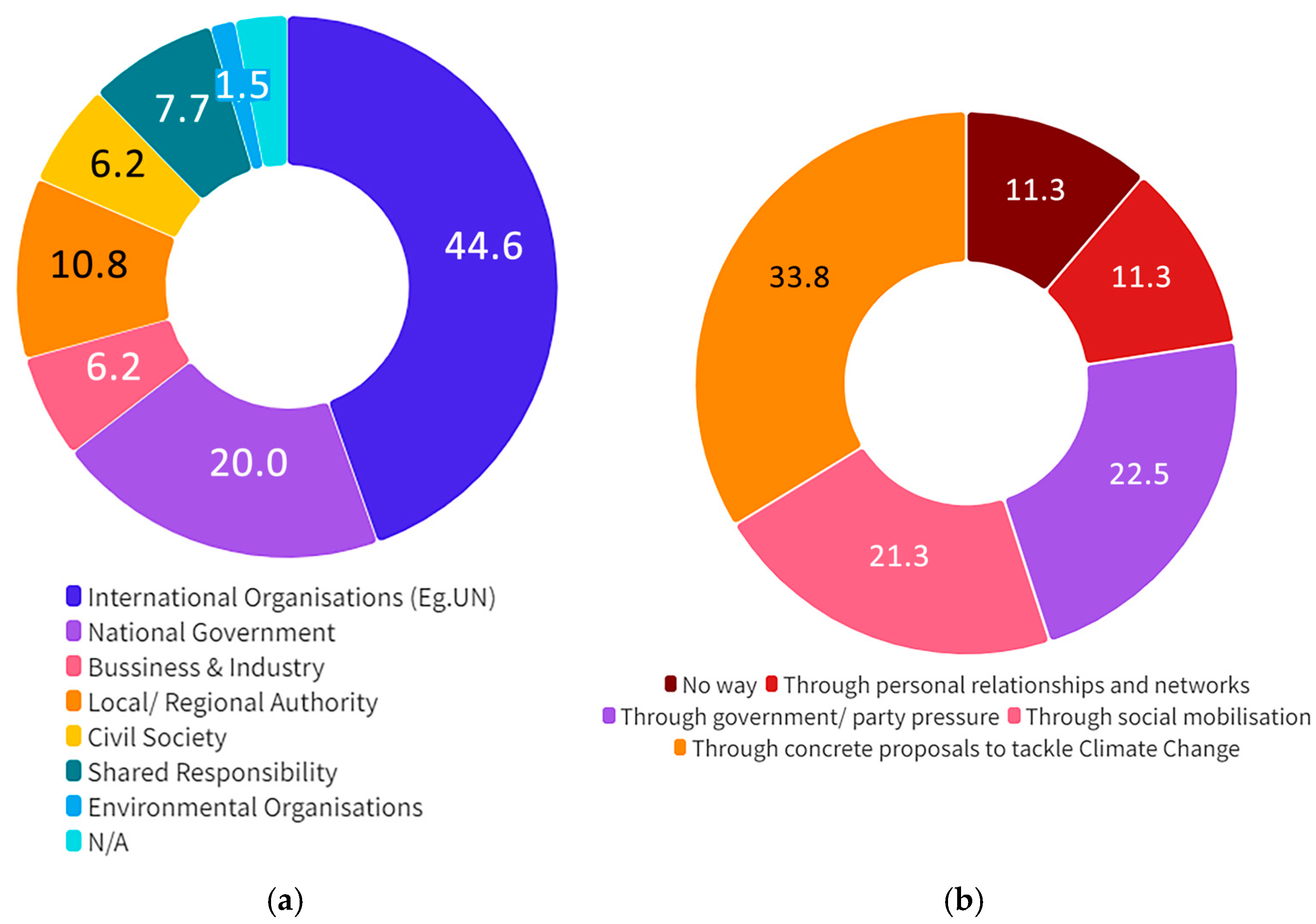

When respondents asked who should lead efforts to combat climate change, 44.6% pointed to international organizations, such as the United Nations, emphasizing the need for a global approach. National governments were cited by 20%, with smaller percentages attributing responsibility to businesses (6.2%), local governments (10.8%), and civil society (6.2%). Some (7.7%) believed responsibility should be shared among all groups (

Figure 8a). Moreover, amongst the sample respondents, 33.8% felt that local governments influenced port environmental policies through specific climate change proposals. Another 22.5% cited government or political pressure, and 21.3% pointed to social mobilization. However, 11.3% believed local governments had no influence (

Figure 8b).

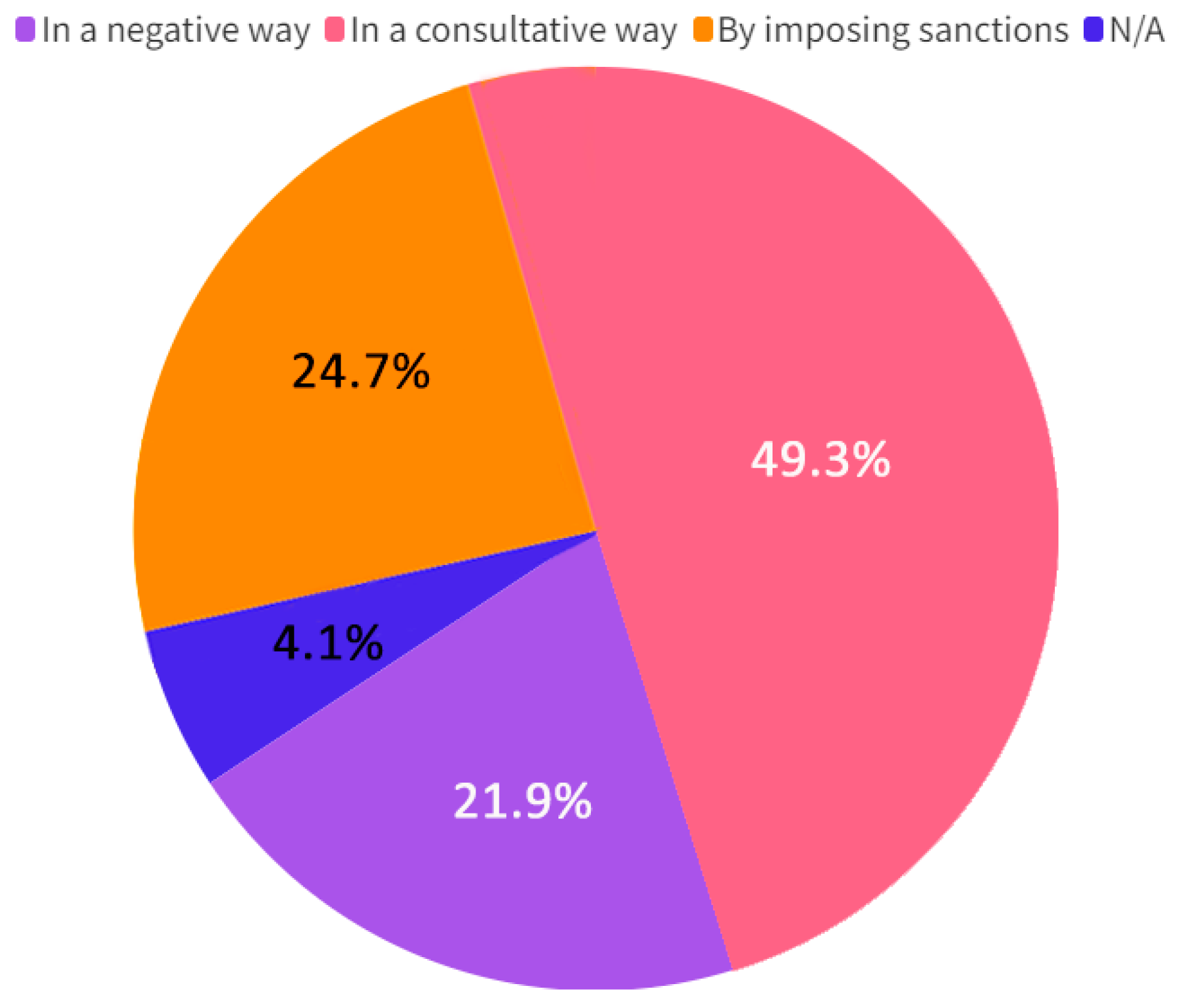

Regarding the role of international organizations in shaping port environmental policy, 49.3% believed they provided guidance in an advisory capacity, while 24.7% viewed them as enforcers of sanctions (

Figure 9). Another 21.9% felt their involvement added unnecessary bureaucracy influencing in a negative way, and 4.1% were undecided. The European Union was seen as the most influential body in port regulations (31.4%), followed by the International Maritime Organization (24.8%) and the European Sea Ports Organization (13.3%); however, the ESPO does not produce regulations but rather provides guidance on good practices and roadmaps for environmental issues. Other organizations, such as the UN and Hellenic Ports Association, were seen as less influential.

Stakeholders were seen as influential in shaping port environmental policies by 75.4% of respondents, while 18.5% believed they had no impact, and 6.2% were uncertain. The analysis revealed that conflicts of interest exerting influence on port environmental policies were predominantly attributed to domestic private capital (43.1%), followed by international state interests (18.5%) and national state interests (15.4%). Foreign private capital was noted by 12.3% of the respondents, while 7.7% of respondents indicated that they were unsure.

With regard to environmental decision making, 81.5% of respondents identified the board of directors as the primary decision-maker, 13.8% cited the president or CEO as the main decision-maker, and 1.5% identified the head of the environmental department as the key decision-maker.

Amongst the participating ports, 63.1% were described as having no specialized environmental departments at its premises, suggesting a potential gap in organized environmental management. Conversely, 33.8% of respondents, mainly those from port authorities, indicated the presence of such departments, reflecting growing recognition of their importance.

An overwhelming majority (96.9%) agreed that enhanced stakeholder awareness regarding climate change in port settings is imperative; seminars and conferences were identified as the most effective method for raising environmental awareness (51%), followed by electronic media (34%). A smaller percentage of respondents mentioned written materials (12%) and rule enforcement tools (1%).

4.2. Cluster Analysis Outputs

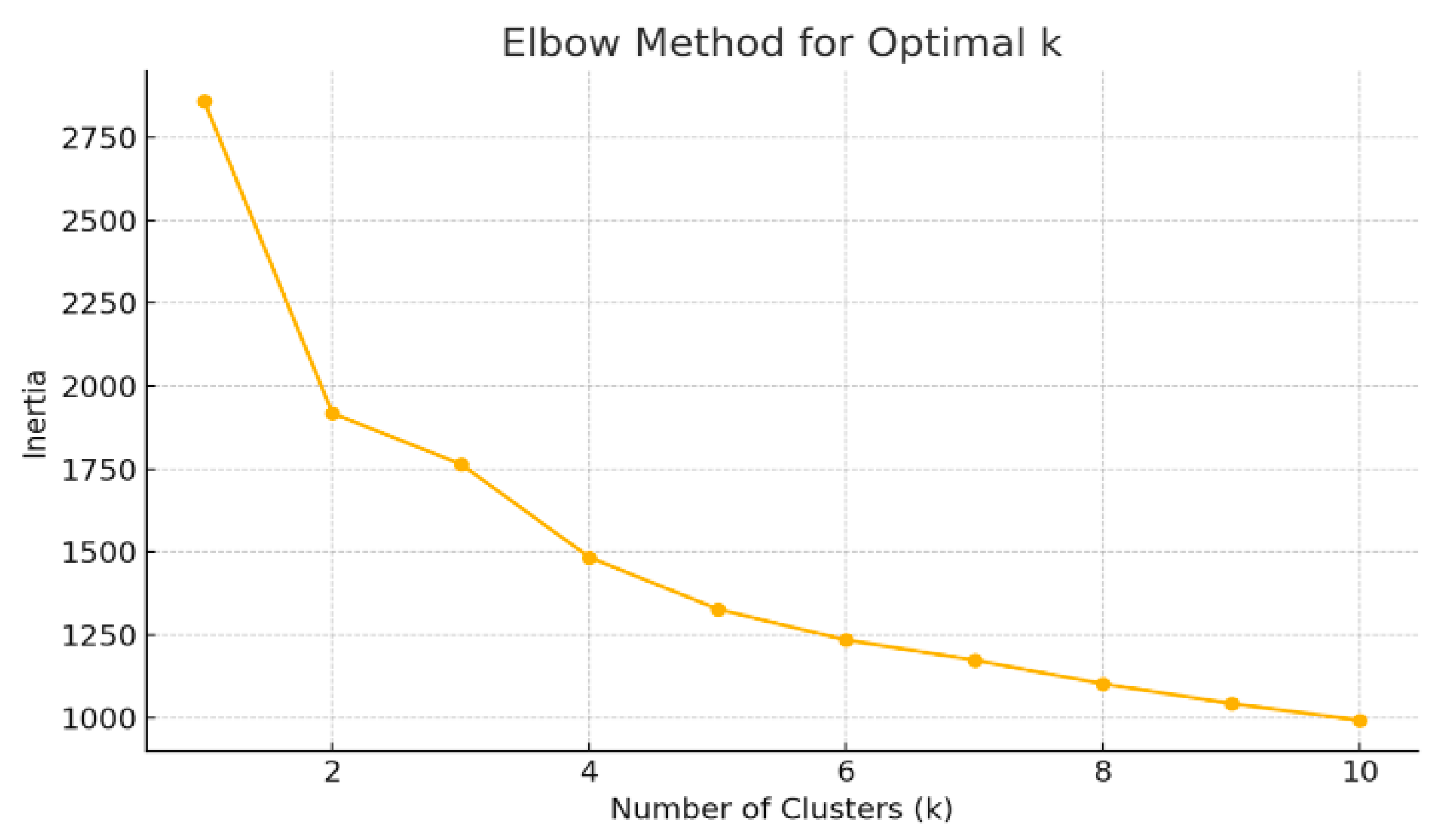

The cluster analysis was used to determine that three clusters provided the best balance between complexity and explanatory power. Additionally, the hierarchical diagram confirmed this conclusion, supporting the decision to segment the data into three distinct clusters. The within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) plot, as shown in

Figure 10, exhibits a clear inflection point, or “elbow,” at k = 3, where the variance decrease starts to flatten noticeably. By showing that adding more clusters would only slightly enhance model fit, this point illustrates the ideal trade-off between explanatory accuracy and model simplicity. The selection of three clusters is supported by the visual break between k = 2 and k = 3, indicating that this structure effectively reflects the primary heterogeneity in the data without overfitting [

54].

The first cluster, which represents a substantial portion (n = 48, 73.8%) of the sample, consists primarily of professionals aged 46–50. Within this cluster, 41.2% hold tertiary education qualifications, and 31% have less than five years of experience in their current organization. These individuals are likely to hold roles related to environmental management or planning. They appear to be engaged with climate-related issues but may be constrained by organizational inertia or external decision-making processes. This group reports experiencing significant impacts from extreme weather events and acknowledges the influence of stakeholders in shaping environmental policy. However, despite expressing confidence in addressing climate challenges, respondents in this cluster indicated that climate-related risks are currently not factored into port infrastructure investment decisions, highlighting a notable disconnect between awareness and institutional action. A large portion of this group works for municipal port funds (66.7%), suggesting that, while these authorities are environmentally aware and actively engaged in daily operations, they may lack the institutional frameworks, funding tools, or long-term planning capacity to transform awareness into formal climate adaptation strategies.

The second cluster (n = 6, 9.2% of the total sample) is dominated by senior professionals, with 66.7% aged of the cluster members being over 55 years old, 66.7% holding postgraduate degrees, and 66.7% having fewer than five years of experience in their current roles. Despite their academic background and leadership status, this group appears more hesitant about the urgency of climate action, as 66.7% report that climate risks are integrated into infrastructure investment decisions. Participants also cite limited access to environmental data as a barrier, suggesting a degree of fragmentation in information flow. This may contribute to a more cautious or skeptical approach to proactive climate planning.

In the third cluster (n = 10, 16.9% of the total sample), most members are aged between 41 and 45 (27.5%), with 45.5% having a tertiary education and organizational experience of under 5 years (63.6%). They are aware of climate-related hazards and generally open to integrating adaptation strategies. In this cluster, 82% of respondents confirmed that climate risks are considered in infrastructure planning, although they also reported that they had not experienced the impacts of CC yet, making them the most investment-forward of the three groups. However, their responses still suggest uneven data availability and moderate institutional support, pointing to a group of concerned professionals who are ready to act but may struggle with resource- or authority-related constraints.

A summary of the clusters’ characteristics based on respondents’ demographic and attitudinal variables is provided in

Table 3.

A further elaboration on the three different clusters identified through K-means analysis reflected demographic and organizational diversity and embody distinct governance and institutional orientations toward climate action. Cluster 0 (mid-career professionals in municipal port funds) represents an awareness–action gap: respondents recognize climate risks yet operate within entities constrained by limited institutional capacity, fragmented funding instruments, and short planning horizons. Their conservative management approach reveals the structural weaknesses of decentralized port governance in Greece, where local entities often lack specialized environmental departments or technical guidance.

Cluster 1, composed mainly of senior professionals in higher administrative positions of port authorities, illustrates a more strategic but hesitant orientation. Their postgraduate qualifications suggest strong theoretical understanding but their lower integration of climate risks into investment decisions reveals the influence of institutional inertia, political accountability concerns, and risk-averse decision cultures. These findings imply broader governance issues such as a fragmentation in information flow and the absence of coherent national coordination mechanisms, which hinder the translation of awareness into concrete adaptation measures.

Cluster 2 demonstrates a pragmatic, action-oriented approach: younger and mid-career professionals exhibit openness to incorporating adaptation measures, aligning their attitudes with EU-level policy framework on energy transition and port resilience. Yet, their implementation capacity remains limited by resource constraints and unclear policy guidance from the state.

The interpretation of these results through a governance perspective provides a structural insight beyond the descriptive analysis. The clustering outcomes reveal that differences in institutional scale, leadership structure, and access to policy information directly shape the degree of adaptation readiness. They point to a multi-level governance challenge where regulatory compliance dominates over strategic foresight. Embedding these clusters as interpretive categories in subsequent analyses (e.g., prioritization of environmental concerns or stakeholder engagement) underscores how governance fragmentation and resource asymmetry explain the uneven diffusion of climate awareness across the Greek port system.

Further elaboration on the different patterns based on the working environment showed that personnel in port authorities tend to be more adequately educated (57% hold postgraduate degrees) and experienced, yet only 22% report integrating climate risks into infrastructure planning, emphasizing a potential disconnect between institutional capacity and environmental responsiveness. On the other hand, employees of municipal port funds are generally newer in their roles (42% with less than 5 years of experience), with moderate educational backgrounds (45% tertiary education), and an even lower rate (16%) of reported climate investment consideration, pointing to resource constraints despite evident awareness.

Moreover, a deeper insight into the small group (10.6%) who expressed skepticism regarding the connection of the observed environmental changes to climate change revealed that this group appears to correspond mainly to Cluster 1 or to fringe elements within Cluster 0; in these clusters, climate awareness is less systematized or is challenged by a lack of technical exposure. Looking at the professional backgrounds of the people expressing these opinions, all of them are employed in municipal port funds; notably, no respondents from port authorities fell into this group, possibly indicating a stronger alignment between larger ports and mainstream climate change narratives. With regard to the relative de-prioritization of climate change as an environmental issue, the findings reveal a connection between Clusters 0 and 2, linked to high awareness but low strategic readiness to act on climate concerns. In relation to the remaining environmental concerns, waste management issues seem to be mainly a component of Cluster 0, water quality issues seem to be mainly a component of Cluster 1, and energy efficiency and ship waste issues seem to be mainly a component of Cluster 2.

4.3. Output of the Interviews

As noted in

Section 4.1, at the methodological level, the semi-structured interviews followed a specific thematic axis. The main themes that were discussed, analyzed, and interpreted are outlined in the following subsections.

4.3.1. Ideological Framework

As expected, the respondents, all of whom hold significant, organic roles within their respective organizations, shared common worldview assumptions regarding the impact of climate change on ports. All of them consider climate change to be a given and real issue, now perceived with a pronounced sense of urgency. This sense of urgency was, by almost unanimous admission, decisively shaped by the recent disasters in the city and port of Volos (5 and 30 September 2023). Within this perspective, a purely economic approach to the relationship between climate change and ports is of fundamental importance. At both a personal level and as a prevailing perception of the general climate within Greek ports, any notion or mentality concerning “environmental ethics” (i.e., the environment as an end in itself) is downgraded; instead, the focus is placed on the economic factor: specifically, the cost–benefit relationship of the port in relation to climate change. Within this framework, there is a unanimous perception of an unwavering yet general goal: the transformation of ports into “smart” and “green” entities. However, this goal is not accompanied by the adoption of concrete policies, directives, or strategic planning.

4.3.2. Cold Ironing (Shore-Side Electricity)

The only shared, direct objective related to mitigating climate change is so-called “Cold Ironing,” which refers to the process of providing shore-side electrical power to ships at berth while their main and auxiliary engines are turned off. “Cold Ironing” stands for the EU Directive 2014/94/EU [

58], which must be implemented by all major ports in the country by 1 January 2030. All three (3) port organizations under examination have moved toward implementing this program, having completed and obtained approval for the necessary technical and scientific studies. At this stage, although the organizations are seeking funding sources for “Cold Ironing,” the situation remains uncertain due to the privatization of the ports and the pending arrival of new investors.

There is a common understanding that the implementation of “Cold Ironing” cannot be realized autonomously by the organizations, as it is an extremely high-cost investment. It is taken for granted that European and/or state subsidies will be necessary. Absolute consensus also exists regarding both the obligation of the organizations to secure funding independently and the necessity of implementing “Cold Ironing.” Beyond the binding EU requirement, the rationale aligns with market economy dynamics: ports that fail to implement “Cold Ironing” will be “automatically” excluded from the market, as the shipping industry is also in a green transition process, seeking green ports as its partners. Consequently, the economic loss for any such port would be substantial.

4.3.3. Challenges and Barriers to Adaptation

According to the research participants, there are several key issues hindering the immediate adaptation of ports to the challenges posed by climate change, which can be grouped into two categories: those related to the existing institutional and legal framework, involving the role of the Greek state, and those linked to individual or personal factors.

All respondents expressed a strong criticism of the current institutional framework concerning energy issues in ports. Although compliance is required within a proposed timeline, the Greek state has not addressed the major problem of financing port organizations. The port authorities are public limited companies (Sociétés Anonymes) classified under the EU regulatory framework as large enterprises, resulting in relatively low levels of European funding. At the same time, there are significant constraints in the energy sector, as the current legal framework prohibits the sale of water and electricity. The participants, especially the CEOs of the three (3) organizations, consider it essential to liberalize the energy market so that ports can become genuine and dynamic “energy players” which are able to manage their own dealing rooms and engage in energy trading through forward contracts. Within this perspective, there is a shared belief that any procrastination by the Greek state in this area will prove, in the medium term, disastrous for port organizations.

At another level, bureaucracy emerges as a critical issue within the broader interactions between ports and the state. Although the research participants were not more specific about this matter, it is important to underline that they directly associate bureaucracy with procrastination, lack of political will, and avoidance of personal accountability, especially within the boards of directors of ports. The picture of deferral and/or stagnation is reinforced by criticism that many board members are appointed solely on partisan criteria. Finally, there was an expressed view regarding the profoundly problematic mentality governing citizen–state relations. According to this perspective, it is preferred that the state, as an impersonal institution, pay any potential fines imposed by international or regional organizations (especially the EU) rather than for any individual to assume personal responsibility for the necessary, sometimes radical, changes society must undertake to confront the challenges of climate change.

5. Discussion

Climate hazards are anticipated to increasingly affect ports worldwide, with escalating consequences as time progresses. Adapting to climate change and building resilience in ports is widely recognized by international society as an urgent priority and a matter of strategic economic importance. Enhancing the climate resilience of ports is a matter of strategic socioeconomic importance, crucial for safeguarding trade and coastal communities.

The research results highlight the complex and multi-level governance landscape shaping climate change policy in ports amongst other environmental policies. The field research results reveal a tendency toward recognizing significant changes in the climate over recent years, with a consensus on the link between harshening weather conditions. A great percentage of stakeholders acknowledge these noticeable shifts in climatic conditions and express concern regarding their impact. Therefore, there is nearly a consensus that climate change is both present and consequential, underscoring the increased concern of its potential impact on ports’ infrastructure, operations, and services in the future. With respect to adaptation measures, participants perceive education as a vital yet challenging component in addressing climate change. They express a clear preference for preventive and educational strategies to promote environmental awareness, placing particular value on exchanging knowledge through industry and academia conferences and digital platforms.

Further elaboration through cluster analysis identified three clusters which served as interpretive lenses throughout the integrated analyses, allowing the discussion to distinguish how governance structures, professional hierarchies, and institutional capacity shape the observed variation in perceptions and policy readiness. Moreover, clustering outcomes identify both individual attitudes and structural imbalances in governance, linking personal perceptions to the policies and institutions shaping port climate resilience in Greece. In particular, the relatively proactive Cluster 2 demonstrates new professional generations and engagement with EU sustainability frameworks encourage openness to adaptation but is limited by the lack of established mechanisms for knowledge sharing. On the other hand, senior professionals (Cluster 1) are cautious or skeptical because, under state control and organization, they usually follow established routines and try to avoid risk. Likewise, they prioritize regulatory compliance and financial caution over innovation, making adaptation planning appear to be a difficult, proactive action. The observed ‘fragmented information flow’ implies a gap between EU policy-making and the way in which local ports implement these policies. Smaller port entities (Cluster 0), operating with limited staff and funding autonomy, depend heavily on central guidance yet receive insufficient technical or financial support, resulting in operational awareness without strategic capacity.

The results of the discourse corpus analysis gave insights into emphatic details. Despite acknowledging climate change concerns, it is revealed that, to some extent, there is a lack of a deeper and broader ‘culture’ of knowledge and awareness regarding the importance of addressing climate change and its impact on ports. For example, in a view that is descriptive rather than normative, climate change in ports is predominantly approached in economic terms, particularly through the framework of cost–benefit analyses.

Through the consolidated analysis, it is noteworthy that, although climate change is acknowledged as a serious threat, its prioritization as an environmental concern remains relatively low, ranking fourth overall, in contrast with the higher emphasis seen in European contexts where climate change has been the port sector’s foremost environmental priority since 2022 [

48]. The latter has also been implied by previous studies in which climate change is not considered to be amongst the crucial environmental issues affecting Greek ports [

62]. Evidence from the statistical analyses of both the questionnaires and the interviews indicates that, in environmental prioritization, impact-mitigation strategies are viewed as the most critical course of action, whilst climate change is predominantly interpreted as a call for energy transition, closely linked to the obligation of complying with the institutional framework for shore-side electricity provision. Specifically, while energy efficiency ranks high, the most proactive stance appears in Cluster 2, which is primarily composed of well-educated, highly aware professionals, indicating their intent to align with EU instruments. Seaport strategies prioritize mitigation and compliance measures over adaptation because these are linked to regulatory obligations and immediate reputational benefits, whereas adaptation is framed as a discretionary expense [

63], indicating that ports are under pressure to maintain throughput and efficiency, which competes with long-term resilience investments [

64]. With respect to the rest environmental issues, waste management constitutes mainly a concern of the smaller ports of Cluster 0, who express environmental concern but often lack mechanisms for integrating the legislative framework, let alone more abstract challenges like climate resilience into strategic planning. On the other hand, Cluster 1, with higher seniority and presence in centralized ports, demonstrates awareness but lower engagement, possibly due to their focus on infrastructure over local environmental performance.

These findings highlight the decisive role that international and, in particular, European organizations play in national policy formation, with EU directives establishing a framework for key decisions; port sector priorities are strongly defined by these policy instruments and their subsequent incorporation into national legislation. Environmental issues such as energy efficiency, waste management, water quality, and ship-generated waste frequently appear higher on the environmental agenda, reflecting a divergence between European-level strategic emphasis on climate adaptation and its comparatively modest prioritization within the Greek port system. In this environmental prioritization, regulatory compliance with European legislation emerges as the top driver of port investments in environmental performance, with ports being primarily motivated by the need to meet international and EU environmental obligations [

65] rather by strategic adaptation planning. Politically, limited strategic guidance has hindered the institutionalization of climate adaptation as a policy priority. Consequently, climate change is perceived in instrumental and reactive terms, addressed mainly through compliance with existing regulatory frameworks rather than as a systemic governance challenge requiring long-term institutional integration.

Moreover, the need for adequate funding for ports is by far the top hierarchical issue in addressing the impacts of climate change. For instance, it was stated that the economic crises of the decade 2010–2020 has had substantial impacts on the financial capacity of ports to meet the goals of climate impacts adaptation, as the energy transition constitutes a long-term process with extremely high costs. Economically, port administrations continue to operate under strong short–medium-term financial constraints and performance pressures, which orient management priorities toward operational efficiency and revenue generation rather than proactive climate adaptation [

14,

19,

66]. This economic framing reinforces the perception of adaptation planning and measures implementation as a cost rather than an investment [

67]; meanwhile, adaptation projects are assumed to be valuable mainly in the case of extreme disasters, contributing minimal value under normal weather conditions [

68]. A fragmented state of readiness at the infrastructure-planning stages, despite broad recognition of climate-related issues, has long been indicated in the UNCTAD port industry survey [

3]. Therefore, regardless the highlighted strategic importance of ports and the severe economic consequences of climate-related disruptions, which stress the need for resilience despite limited resources [

68,

69,

70], adaptation finance flows remain small compared to mitigation; private sector actors often lack incentives because adaptation benefits are diffuse and long-term, making them harder to justify under the current financial performance metrics. Apparently, this inertia goes beyond any skepticism that large-scale adaptation may create environmental trade-offs, calling for systemic and policy-level evaluation [

71].

What is further underscored is the lack of a proactive approach in addressing the issue, especially from the perspective of the Greek state. Although a majority of port stakeholders report having been affected by an extreme weather event, the implementation of tailored and effective measures at the national level is advancing at a slow pace. Many ports have yet to engage in the essential preparatory steps—largely due to financial constraints—that are critical for effective adaptation, such as specialized research or systematic risk assessments; these would support informed and effective adaptation planning. It is noteworthy that smaller ports, despite being more exposed to climate change impacts, have not yet incorporated these concerns into upcoming port planning—this is a trend that appears to be closely associated with responses from participants representing major port authorities.

Furthermore, a central consideration of the role played by local authorities and stakeholders in shaping environmental policies is identified. The most characteristic problem that emerged from the interviews is the absence of a clear decision-making role and collaborative process among port authorities, the Greek state, and the EU; inclusive stakeholder participation and effective information dissemination are essential in improving cooperation and addressing vulnerabilities in port governance [

7,

35]. The existing institutional gap becomes rather apparent here, and seems to stem mainly from the lack of an organizing role by the Greek state. At the same time, participants perceive that the primary responsibility for addressing climate change should reside within global political institutions, emphasizing the necessity of a coordinated international approach to effectively combating the phenomenon. This lack of a clear coordination system highlights the need for governance quality as a key determinant of resilience [

72]. Effective port management depends on clear organizational structures, stakeholder collaboration, and mechanisms for resource monitoring, all of which strengthen adaptive capacity and preparedness [

36,

37,

73,

74]. Conversely, fragmented governance, poor communication, and limited institutional alignment are shown to undermine resilience, particularly in complex, multi-level systems such as ports. The results point to a critical need for greater transparency, improved access to information, and more effective mechanisms for addressing conflicts of interest—particularly those arising from the involvement of private capital in port development and operations. Transparency and active stakeholder participation are widely recognized as key components in effective and accountable decision making in climate change adaptation [

75,

76]. Considering that the boards of directors are the primary decision-makers for environmental decisions in ports, with minimal involvement of specialized departments, a disconnect between strategic commitments and operational capacity is highlighted; this underscores the need to strengthen institutional frameworks and establish dedicated environmental units. Last but not least, the matter of bureaucracy emerged as a critical problem, which carries at least two important dimensions. On the one hand, the complexity of bureaucratic procedures and their entanglement with the existing legal framework—which has not been modified in line with the new needs that arise from climate change—lead to a serious slowdown in mitigation and/or adaptation efforts [

77]. At another level, some interviewees highlighted the longstanding challenge faced by the Greek public administration: the appointment of staff to key positions in port authorities based more on non-technical criteria. This practice has implications for ports’ environmental policy; limited technical knowledge and, in some cases, a lack of engagement with job responsibilities hinder effective adaptation to the challenges posed by climate change. Understandably, the avoidance of taking such initiatives and the responsibilities they entail leads to procedures that are either excessively delayed or remain in a state of limbo.

Institutional and governance issues are stated as major obstacles to making ports climate-resilient; unclear rules, fragmented responsibilities, and lack of legal guidance slow down decisions and make adaptation seem optional. In the absence of clear institutional accountability policy mechanisms, many strategic initiatives remain unimplemented [

78,

79]. To move forward, ports need better coordination among stakeholders, including all operators, regulators, and local communities, so that adaptation becomes part of core planning [

66]. Inclusive engagement strengthens governance by reducing fragmentation and clarifying roles, which accelerates decision making [

79]. It also builds adaptive capacity through knowledge sharing, as local actors contribute context-specific insights that improve risk assessments and planning [

66]. Moreover, stakeholder participation enhances legitimacy and social acceptance, making it easier to implement costly measures and comply with EU climate directives. Finally, participatory processes often unlock access to climate finance, as international donors and IFIs increasingly require evidence of stakeholder-informed strategies [

69,

78]. Together, these factors show that SP is both a procedural step and a structural enabler of resilient port governance.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the perceptions, preparedness, and institutional regime influencing climate change adaptation across Greek ports. Using a mixed-methods approach—including structured questionnaires and targeted interviews—the analysis revealed significant variations in awareness and adaptive readiness among ports of different sizes, governance models, and resource capacities.

The key findings indicate that, while port stakeholders broadly recognize the tangible risks posed by climate hazards—particularly extreme wind events—this awareness does not consistently translate into strategic adaptation planning. For most participants, climate change remains a secondary concern relative to other environmental priorities, especially in smaller, locally managed ports. Adaptation actions are primarily guided by compliance with existing institutional frameworks rather than proactive, forward-looking strategies.

Financial constraints emerged as a central barrier, determining the extent and timing of adaptation actions. Limited access to funding, fragmented governance, and constrained institutional capacities further impede the integration of climate adaptation into port planning, particularly within municipal and state port funds. Structural challenges, including appointments to key port authority positions without technical expertise, exacerbate delays in implementing necessary adaptation measures.

European and international regulatory frameworks play an influential role in shaping national port policies, highlighting the dependence of climate strategies on EU-level guidance and support. Current institutional priorities focus largely on energy efficiency, waste management, and water quality, leaving climate adaptation underemphasized.

Based on the research outcomes, a set of actions and policies can be proposed which might lead to an increase in port stakeholders’ awareness, enabling us to confront the revealed shortages and knowledge gaps. At a national level, an understanding of the impacts of climate change should be systematically incorporated into the formulation and implementation of port policies. While some progress has been made, such as the inclusion of climate change impact assessments in Port Master Plan studies, a coherent and comprehensive national policy has yet to be established. The existing port governance scheme also poses a barrier, as multiple ministries are involved in and supervise different aspects of port operations, which in turn affects the financing schemes of port investments. Regarding the financing potentials of climate change adaptation and mitigation measures, the Greek port system shows different levels of financing ability. On the one hand, the two major Greek ports—Piraeus and Thessaloniki—have the capacity to finance the necessary investments independently, either through their own capital resources or via loans. On the other hand, the port authorities responsible for medium-sized ports operate with constrained financial resources, with ownership structures varying between private entities and the state. Finally, there are smaller ports, which operate as municipal or state port funds, which lack the financial capacity to support almost any investment related to climate change adaptation or mitigation. As such—taking into account the pivotal role of ports in supporting the national economy and preserving social cohesion—the establishment of a comprehensive state intervention mechanism is imperative. Such a framework should aim to safeguard the financial sustainability of smaller ports, with particular priority given to those located on the islands; these are often the most vulnerable to isolation and climate-related risks. At a port level, port authorities must implement the following measures:

- ○

Develop specialized environmental and climate units within port authorities to oversee adaptation planning and implementation.

- ○

Establish funding mechanisms to support climate adaptation investments, prioritizing smaller and island ports that lack financial autonomy.

- ○

Incorporate climate change resilience considerations in Port Master Plans, business plans, and broader national port policies to support systematic, long-term resilience planning.

- ○

Initiate a social dialogue at a local level with port stakeholders, aiming to increase awareness about the impacts of climate change and foster cooperation between authorities and society.

Moreover, cooperation and synergies between port authorities are required, which should aim to achieve the following goals:

- ○

Develop a common general strategy regarding climate change.

- ○

Exchange good practices in support of port resilience to the impacts of climate change.

- ○

Develop educational and training programs for port personnel.

Τhe aforementioned measures are expected to provide a framework for a preliminary approach to climate change, addressing both port-level and national-level actions with the objective of strengthening port resilience.