Reimagining Heritage Tourism Through Co-Creation: Insights from Prenggan Tourism Village, Yogyakarta

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can the cultural heritage identity and characteristics of Prenggan Village be authentically integrated into meaningful tourist experiences?

- How do tourists perceive and experience elements of local wisdom during their visits?

- What local-wisdom-based management strategies can enhance tourist experience quality and support cultural preservation?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Heritage Identity

2.2. Co-Creation of Tourist Experience

2.3. Tourist Experience in Heritage-Based Destinations

2.4. Sustainable Heritage Tourism and SDG Linkages

2.5. Cultural Identity Theory and Tourism Experience Design

2.6. Hypothesis Development

2.6.1. Cultural Heritage Identity and Local Wisdom

2.6.2. Co-Creation Value and Local Wisdom

2.6.3. Local Wisdom and Tourist Heritage Experience

2.6.4. Mediating Role of Local Wisdom

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

- Local community members and artisans involved in cultural preservation and tourism activities;

- Village tourism managers and guides responsible for heritage interpretation and visitor engagement;

- Domestic tourists (n = 208) who have visited Prenggan Village within the past 12 months.

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

3.3.1. Qualitative Analysis

3.3.2. Quantitative Analysis

- Measurement Model Assessment

- 2.

- Structural Model Assessment

3.4. Triangulation and Validation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Measurement (Outer) Model Evaluation

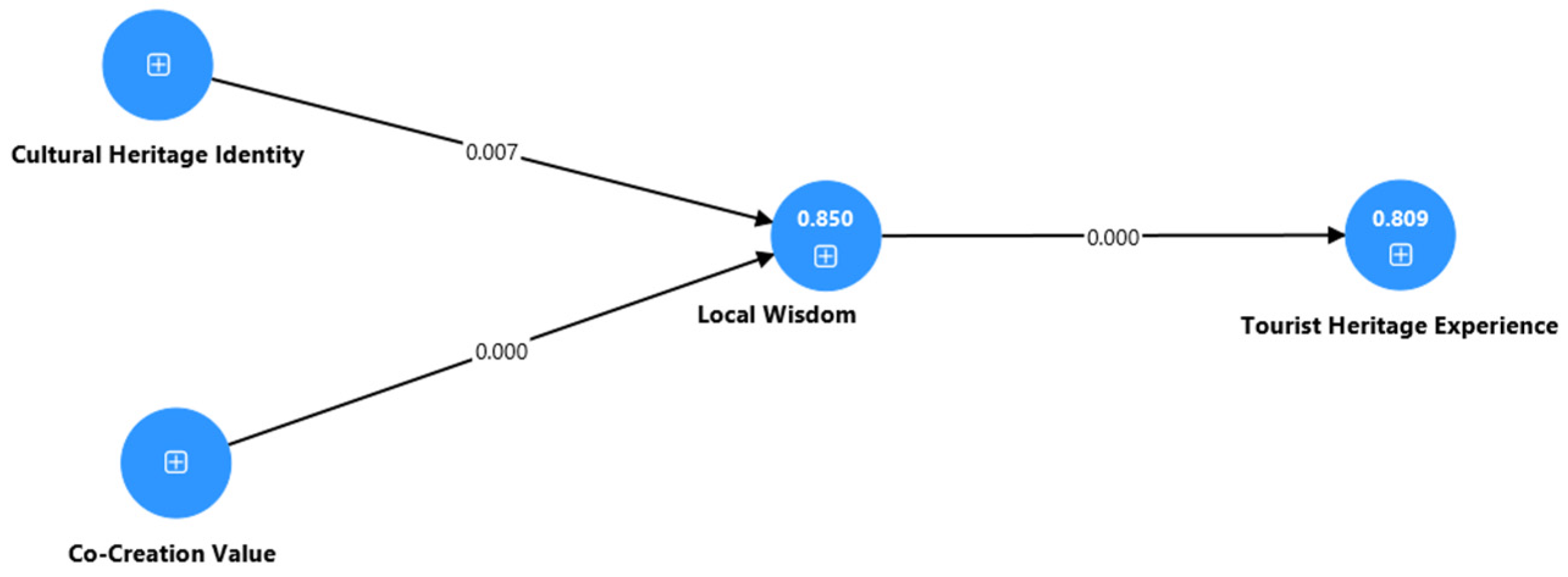

4.3. Inner Model Evaluation

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Recommendations

7. Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arumugam, A.; Nakkeeran, S.; Subramaniam, R. Exploring the Factors Influencing Heritage Tourism Development: A Model Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, S.; Vandini, M. Resilience and Sustainable Territorial Development: Safeguarding Cultural Heritage at Risk for Promoting Awareness and Cohesiveness Among Next-Generation Society. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaonkar, S.; Sukthankar, S.V. Measuring and evaluating the influence of cultural sustainability indicators on sustainable cultural tourism development: Scale development and validation. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Oancea, O.A. Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage 2024, 7, 4354–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Sihombing, S.O.; Antonio, F. Unveiling memorable tourism experiences effect on positive EWOM: Focus on the role of positive and negative emotion. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2557073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicu, I.C.; Fatorić, S. Climate change impacts on immovable cultural heritage in polar regions: A systematic bibliometric review. WIREs Clim. Change 2023, 14, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Tong, Y.; Li, Q.; Wall, G.; Wu, X. Interaction Rituals and Social Relationships in a Rural Tourism Destination. J. Travel Res. 2022, 62, 1480–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, X. Identification Model of Traditional Village Cultural Landscape Elements and Its Application from the Perspective of Living Heritage—A Case Study of Chentian Village in Wuhan. Buildings 2024, 14, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, H. Integrating Community Fabric and Cultural Values into Sustainable Landscape Planning: A Case Study on Heritage Revitalization in Selected Guangzhou Urban Villages. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Sihombing, S.O.; Antonio, F.; Sijabat, R.; Bernarto, I. The Role of Tourist Experience in Shaping Memorable Tourism Experiences and Behavioral Intentions. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 1319–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemy, D.M.; Pramono, R. Juliana Acceleration of Environmental Sustainability in Tourism Village. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemy, D.M.; Pramezwary, A.; Juliana, P.R.; Qurotadini, L.N. Explorative Study of Tourist Behavior in Seeking Information to Travel Planning. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Pramezwary, A.; Djakasaputra, A.; Anwar, M.M.; Jie, F. The missing link in urban tourism: Connecting leisure, accessibility and resident participation for enhanced value. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2556473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, Z. Heritage Tourism and Nation-Building: Politics of the Production of Chinese National Identity at the Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Li, Z. Cultural ecology cognition and heritage value of huizhou traditional villages. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Shu, Z.; Liu, Y. Exploring the role of place attachment in shaping sustainable behaviors toward marine cultural heritage: A case study of Dongmen village in Fujian Province, China. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1476308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, J. Recognition of Values of Traditional Villages in Southwest China for Sustainable Development: A Case Study of Liufang Village. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Toukoumidis, A.; Marín-Gutiérrez, I.; Hinojosa-Becerra, M. Ancestral Rituals Heritage as Community-Based Tourism—Case of the Ecuadorian Andes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.-C.M.; French, J.A.; Lee, C.; Watabe, M. The symbolism of international tourism in national identity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Stoffelen, A.; Bolderman, L.; Groote, P. Place agency and visitor hybridity in place-making processes at sacred heritage sites. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, P.; Song, H. Multiple Effects of Agricultural Cultural Heritage Identity on Residents’ Value Co-Creation—A Host–Guest Interaction Perspective on Tea Culture Tourism in China. Agriculture 2024, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, I.; Hubner, B.; Sianipar, R.; Indra, F.; Djakasaputra, A. Systematic Literature Review: Combining Foodscape and Touristcape for International Tourism Marketing in Singapore and Batam. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control. 2024, 545, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Pramezwary, A.; Lemy, D.M.; Teguh, F.; Djakasaputra, A.; Sianipar, R. Antecedents Experiential Commitment and Consequences in Willingness to Post Photo and Behavioral Intention Toward the Destination. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2022, 17, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Nagoya, R.; Bangkara, B.A.; Purba, J.T.; Fachrurazi, F. The role of supply chain on the competitiveness and the performance of restaurants. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 10, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Sianipar, R.; Lemy, D.M.; Pramezwary, A.; Pramono, R.; Djakasaputra, A. Factors Influencing Visitor Satisfaction and Revisit Intention in Lombok Tourism: The Role of Holistic Experience, Experience Quality, and Vivid Memory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 2503–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Hubner, I.B.; Lemy, D.M.; Pramezwary, A.; Djakasaputra, A. Antecedents of Happiness and Tourism Servicescape Satisfaction and the Influence on Promoting Rural Tourism. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 4041–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; 515p, Available online: https://worldcat.org/title/1414174647 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; 291p, Available online: https://worldcat.org/title/1334726603 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswel, J.D. Research Design. In Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, M.; Sezerel, H.; Uzuner, Y. Sharing experiences and interpretation of experiences: A phenomenological research on Instagram influencers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 3034–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Rather, R.A.; Hall, C.M. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N. Theoretical linkages between well-being and tourism: The case of self-determination theory and spiritual tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, W. Cultural Perception of Tourism Heritage Landscapes via Multi-Label Deep Learning: A Study of Jingdezhen, the Porcelain Capital. Land 2025, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.H.-Y.; Lin, S.-C.; Lai, S.-C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Yi-Fong, C.; Lee, Y.-T.; Berkes, F. Taiwanese Indigenous Cultural Heritage and Revitalization: Community Practices and Local Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.A.R.; Villalobos, L.G.; de Oliveira, C.P.T.; González, E.M.P. Cultural Identity: A Case Study in The Celebration of the San Antonio De Padua (Lajas, Perú). Heritage 2022, 6, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settimini, E. Cultural landscapes: Exploring local people’s understanding of cultural practices as “heritage”. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Singh, S.; Bhutoria, A.; Doğan, H.A. Placemaking Through Time in Nepal: Conceptualising the Historic Urban-Rural Landscape of Kathmandu. Urban Plan. 2025, 10, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ryan, C.; Deng, Z.; Gong, J. Creating a softening cultural-landscape to enhance tourist experiencescapes: The case of Lu Village. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Gu, X.; Fu, T.; Ren, Y.; Sun, Y. Trends and Future Directions in Research on the Protection of Traditional Village Cultural Heritage in Urban Renewal. Buildings 2024, 14, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwandi, E.; Sabana, S.; Kusmara, A.R.; Sanjaya, T. Urban villages as living gallery: Shaping place identity with participatory art in Java, Indonesia. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2023, 10, 2247671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddapati, J.R. Preserving Tradition Amidst Modern Schooling: The Interplay of Education and Cultural Identity in the Lisu (Yobin) Tribe. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 7, 35650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Buranaut, I. Study on the Interaction Between Agricultural Practices, Religious Activities, and Cultural Relics. Nakhara J. Environ. Des. Plan. 2025, 24, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, C.; Qiu, B. Effects of Urban Landmark Landscapes on Residents’ Place Identity: The Moderating Role of Residence Duration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Shen, Z.; Bhatta, K.D. Cultural Heritage Deterioration in the Historical Town ‘Thimi’. Buildings 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lu, Y.; Martin, J. A Review of the Role of Social Media for the Cultural Heritage Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parani, R. Juliana A Storytelling-Based Marketing Strategy Using the Sigale-Gale Storynomics as a Communication Tool for Promoting Toba Tourism. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Sihombing, S.O.; Antonio, F. What Drives Memorable Rural Tourism Experience: Evidence from Indonesian Travelers. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 2401–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silitonga, P.; Juliana, J.; Rini, G.P.; Sitohang, A.P.S. Unveiling the Outcome of the Implementation of Experiential Value Co-Creation on the Behavioral Intention of Online Travelers. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, T.; Al Isra, A.B.; Tiro, S. Cultural Resilience and Syncretism: The Towani Tolotang Community’s Journey in Indonesia’s Religious Landscape. J. Ethn. Cult. Stud. 2023, 10, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M. Influences of Rural Heritage on Resident Participation in Community Activities: A Case Study of the Villages of Jeoji-ri and Handong-ri on Jeju Island, South Korea. J. People Plants Environ. 2022, 25, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. Understanding the influencing factors of tourists’ revisit intention in traditional villages. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Smith, L. Bonding and dissonance: Rethinking the Interrelations Among Stakeholders in Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamawati, I.G.A.; Jie, F.; Hatane, S.E. Cultural Change Shapes the Sustainable Development of Religious Ecotourism Villages in Bali, Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The use of heritage in the place-making of a culture and leisure community: Liangzhu Culture Village in Hangzhou, China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2024, 30, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsurang, P.; Kiatthanawat, A.; Sanoamuang, P.; Kraseain, A.; Pinijvarasin, W.; Hamid, N. Community-based tourism and heritage consumption in Thailand: An upside-down classification based on heritage consumption. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2096531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Research on the Cultural Landscape Features and Regional Variations of Traditional Villages and Dwellings in Multicultural Blending Areas: A Case Study of the Jiangxi-Anhui Junction Region. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Aoki, N.; Chen, P. Reappropriating the communal past: Lineage tradition revival as a way of constructing collective identity in Huizhou, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baan, A.; Allo, M.D.G.; Patak, A.A. The cultural attitudes of a funeral ritual discourse in the indigenous Torajan, Indonesia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, L.; Xiang, C.; Dai, W. Revitalizing Rural Landscapes: Applying Cultural Landscape Gene Theory for Sustainable Spatial Planning in Linpu Village. Buildings 2024, 14, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurgó, B.; Smith, M.K. The value of cultural ecosystem services in a rural landscape context. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.; Waterton, E.; Saul, H.; Renzaho, A. Exploring the relationships between heritage tourism, sustainable community development and host communities’ health and wellbeing: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenzer, M. Social Landscape Characterisation: A people-centred, place-based approach to inclusive and transparent heritage and landscape management. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 30, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Parji; Maruti, E.S.; Wahyuni, R.S. Cultural resilience study: The role of the temanten mandi ritual in Sendang Modo on the survival of the surrounding community. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2024, 11, 2304401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Fan, W. Formulating sustainable planning for Goulan Yao Village based on the integration of cultural landscape gene theory and spatial analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyasapwatthana, D. Study on Cultural Identity and Tourism Transformation in Santichon Village. Int. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2025, 10, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimache, A.; Qiu, Z. Reading the Identity of Dark Heritage Sites: A Peircean Semiotic Methodology. J. Travel Res. 2023, 63, 1411–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, S.; Guan, B.; Sun, J.; Chen, H. Evaluating the sustainability of rural complex ecosystems during the development of traditional farming villages into tourism destinations: A diachronic emergy approach. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presti, O.L.; Carli, M.R. Italian Catacombs and Their Digital Presence for Underground Heritage Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Trillo, C.; Makore, B.N. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development Targets: A Possible Harmonisation? Insights from the European Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Kukreja, V.; Bordoloi, D. Heritage Coin Identification using Convolutional Neural Networks: A Multi-Classification Approach for Numismatic Research. In Proceedings of the 2023 Second International Conference on Augmented Intelligence and Sustainable Systems (ICAISS), Trichy, India, 23–25 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, A.M.; Dezsi, Ș.; Pop, F.; Cecilia, P. Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania). Sustainability 2022, 14, 16295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemy, D.M.; Juliana, J.; Pramezwary, A. Cultural Value in the Digital Age: Combining Smart Travel Technology with Traveler Satisfaction and Loyalty. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2025, 20, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favargiotti, S.; Pianegonda, A. The Foodscape as Ecological System. Landscape Resources for R-Urban Metabolism, Social Empowerment and Cultural Production. In Urban Services to Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Cultural Memories and Sense of Place in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Masrah Al Salam, the Demolished Theatre Context in Alexandria, Egypt. Land 2020, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P.; Dias, A.L.; Patuleia, M. The Impacts of Tourism on Cultural Identity on Lisbon Historic Neighbourhoods. J. Ethn. Cult. Stud. 2020, 8, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M. Elevating Shunde cultural heritage through dining; A case study of Holiday Inn Shunde in Zhongshan, China. Gulf J. Adv. Bus. Res. 2024, 2, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Parani, R.; Sitorus, N.I.B.; Pramono, R.; Maleachi, S. Study of Community Based Tourism in the District West Java. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qin, J. From digital museuming to on-site visiting: The mediation of cultural identity and perceived value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchumnong, A.; Kozak, M. Impacts of tourism on cultural infiltration at a spiritual destination: A study of Ban Wangka, Thailand. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 15, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutberlet, M. Geopolitical imaginaries and Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) in the desert. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 24, 549–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Zagalo, N.; Vairinhos, M. Towards participatory activities with augmented reality for cultural heritage: A literature review. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2023, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C. Beyond cultural competence: Transforming teacher professional learning through Aboriginal community-controlled cultural immersion. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2019, 60, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryllakis, N.; Matsiola, M. Digital audiovisual content in marketing and distributing cultural products during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Arts Mark. 2023, 13, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage—A Review of Recurrent and Interlinked Themes. Geosciences 2022, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, C.M.R.M.S.; Ray, N.P.D.S. Review of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriuchi, E.; Landers, V.M.; Colton, D.; Hair, N. Engagement with chatbots versus augmented reality interactive technology in e-commerce. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 29, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Xie, G.; Liu, C. Assessment of Society’s Perceptions on Cultural Ecosystem Services in a Cultural Landscape in Nanchang, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, K. The Heritage Given: Cultural Landscape and Heritage of the Vistula Delta Mennonites as Perceived by the Contemporary Residents of the Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.D.; Creswell, J.W.D.; Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research and Design Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; Salmon, H., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781506386768. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Method for Business Textbook: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazali, R.M.; Radha, J.Z.R.R.R.; Mokhtar, M.F. Tourists’ Emotional Experiences At Tourism Destinations: Analysis of Social Media Reviews. J. Event Tour. Hosp. Stud. 2021, 1, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Lee, S.K.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Kiatkawsin, K. Tourist-Perceived Quality and Loyalty Intentions towards Rural Tourism in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skavronskaya, L.; Moyle, B.; Scott, N.; Schaffer, V. Collecting Memorable Tourism Experiences: How Do ‘wechat’? J. China Tour. Res. 2020, 16, 424–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifci, I. Testing self-congruity theory in Bektashi faith destinations: The roles of memorable tourism experience and destination attachment. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widianingsih, I.; Abdillah, A.; Herawati, E.; Dewi, A.U.; Miftah, A.Z.; Adikancana, Q.M.; Pratama, M.N.; Sasmono, S. Sport Tourism, Regional Development, and Urban Resilience: A Focus on Regional Economic Development in Lake Toba District, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramono, R.; Hidayat, J.; Dharmawan, C. Juliana Hybrid Bamboo and Batik Handicraft Development as Creative Tourism Product. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2021, 16, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parani, R.; Hubner, I.B.; Juliana; Purba, H. The Kebo Ketan ritual art as a communication process in delivering the message of social cohesiveness in the Sekaralas village community, Ngawi, East-Java. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2297724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Joseph, F. Essentials of Business Research Methods; Routledge Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basco, R.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Advancing family business research through modeling nonlinear relationships: Comparing PLS-SEM and multiple regression. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 2022, 13, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, M.; Ringle, J.F.; Sarstedt, C.M. PLS-SEM: Indeed A Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2018, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, G.; Hult, M.; Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Juliana; Hubner, I.B.; Pramono, R.; Lemy, D.M.; Pramezwary, A.; Djakasaputra, A. Ecotourism Empowerment and Sustainable Tourism BT—Opportunities and Risks in AI for Business Development: Volume 1; Alareeni, B., Elgedawy, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Swizerland, 2024; pp. 161–172. ISBN 978-3-031-65203-5. [Google Scholar]

- Geçikli, R.M.; Turan, O.; Lachytová, L.; Dağlı, E.; Kasalak, M.A.; Uğur, S.B.; Guven, Y. Cultural Heritage Tourism and Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazanova, M.; Silva, F.M.; de Freitas, I.V. Tourists’ Views on Sustainable Heritage Management in Porto, Portugal: Balancing Heritage Preservation and Tourism. Heritage 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G. Driving Sustainable Cultural Heritage Tourism in China through Heritage Building Information Modeling. Buildings 2024, 14, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, S.; Mittal, A.; Tandon, U. Accessing vicarious nostalgia and memorable tourism experiences in the context of heritage tourism with the moderating influence of social return. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 860–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Garrod, B.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Seyfi, S.; Cifci, I.; Vo-Thanh, T. Antecedents of memorable heritage tourism experiences: An application of stimuli–organism–response theory. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Aditi, B.; Nagoya, R.; Wisnalmawati, W.; Nurcholifah, I. Tourist visiting interests: The role of social media marketing and perceived value. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Djakasaputra, A.; Pramezwary, A.; Lemy, D.M.; Hubner, I.B. Fachrurazi Halal Awareness and Lifestyle on Purchase Intention; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 927. [Google Scholar]

- Goeltom, V.A.H.; Kristiana, Y.; Juliana; Pramono, R.; Purwanto, A. The influence of intrinsic, extrinsic, and consumer attitudes towards intention to stay at a Budget Hotel. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Parta, I.B.M.W.; Maharani, I.A.K. Cultural Tourism In Indonesia: Systematic Literature Review. Vidyottama Sanatana Int. J. Hindu Sci. Relig. Stud. 2023, 7, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Sun, Y.; Wall, G.; Min, Q. Agricultural heritage conservation, tourism and community livelihood in the process of urbanization—Xuanhua Grape Garden, Hebei Province, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 25, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Ma, J.; Xiong, X. Touristic experience at a nomadic sporting event: Craving cultural connection, sacredness, authenticity, and nostalgia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Bogicevic, V.; Bujisic, M. The effect of nostalgia on hotel brand attachment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Lorenzo, A.; Lyu, J.; Babar, Z.U. Tourism and Development in Developing Economies: A Policy Implication Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Lyu, J.; Alam, M.; Khan, M.M.; Nurunnabi, M. The quest of tourism and overall well-being: The developing economy of Pakistan. PSU Res. Rev. 2020, 5, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Cocreation of tourism experiences: Are food-related activities being explored? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Bhandari, H.; Chand, P.K. Anticipated positive evaluation of social media posts: Social return, revisit intention, recommend intention and mediating role of memorable tourism experience. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 16, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Sihombing, S.O.; Suwu, S.E. Community-Based Ecotourism in Sawarna Tourism Village. Enrich. J. Manag. 2023, 13, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapidi, I. Heritage policy meets community praxis: Widening conservation approaches in the traditional villages of central Greece. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 81, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana; Sihombing, S.O.; Antonio, F. Determinants and Consequences of Memorable Tourism Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review BT—Achieving Sustainable Business Through AI, Technology Education and Computer Science: Volume 1: Computer Science, Business Sustainability, and Competitive; Hamdan, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Juliana, J. The effect of supplier performance and transformational supply chain leadership style on supply chain performance in manufacturing companies. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 10, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | R-Square | R-Square Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| Local Wisdom | 0.850 | 0.849 |

| Tourist Heritage Experience | 0.809 | 0.808 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Creation Value | 0.948 | 0.949 | 0.960 | 0.828 |

| Cultural Heritage Identity | 0.920 | 0.924 | 0.940 | 0.759 |

| Local Wisdom | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.958 | 0.851 |

| Tourist Heritage Experience | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.965 | 0.820 |

| Co-Creation Value | Cultural Heritage Identity | Local Wisdom | Tourist Heritage Experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Creation Value | ||||

| Cultural Heritage Identity | 0.742 | |||

| Local Wisdom | 0.813 | 0.769 | ||

| Tourist Heritage Experience | 0.825 | 0.861 | 0.804 |

| VIF | |

|---|---|

| CCV → LW | 3.619 |

| CHI → LW | 3.619 |

| LW → THE | 1.000 |

| Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-Values | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCV → LW | 0.742 | 0.080 | 9.321 | 0.000 | Hypothesis Supported |

| CHI → LW | 0.204 | 0.083 | 2.468 | 0.007 | Hypothesis Supported |

| LW → THE | 0.899 | 0.022 | 41.751 | 0.000 | Hypothesis Supported |

| Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCV → THE | 0.667 | 0.076 | 8.832 | 0.000 | Hypothesis Supported |

| CHI → THE | 0.184 | 0.075 | 2.465 | 0.007 | Hypothesis Supported |

| CCV → LW → THE | 0.667 | 0.076 | 8.832 | 0.000 | Hypothesis Supported |

| CHI → LW → THE | 0.184 | 0.075 | 2.465 | 0.007 | Hypothesis Supported |

| CCV → LW | 0.742 | 0.080 | 9.321 | 0.000 | Hypothesis Supported |

| CHI → LW | 0.204 | 0.083 | 2.468 | 0.007 | Hypothesis Supported |

| LW → THE | 0.899 | 0.022 | 41.751 | 0.000 | Hypothesis Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juliana, J.; Indra, F.; Sianipar, R.; Djakasaputra, A.; Effendy, L. Reimagining Heritage Tourism Through Co-Creation: Insights from Prenggan Tourism Village, Yogyakarta. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411112

Juliana J, Indra F, Sianipar R, Djakasaputra A, Effendy L. Reimagining Heritage Tourism Through Co-Creation: Insights from Prenggan Tourism Village, Yogyakarta. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411112

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuliana, Juliana, Febryola Indra, Rosianna Sianipar, Arifin Djakasaputra, and Linda Effendy. 2025. "Reimagining Heritage Tourism Through Co-Creation: Insights from Prenggan Tourism Village, Yogyakarta" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411112

APA StyleJuliana, J., Indra, F., Sianipar, R., Djakasaputra, A., & Effendy, L. (2025). Reimagining Heritage Tourism Through Co-Creation: Insights from Prenggan Tourism Village, Yogyakarta. Sustainability, 17(24), 11112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411112