A Life-Cycle Cost Analysis on Photovoltaic (PV) Modules for Türkiye: The Case of Eskisehir’s Solar Market Transactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Economics of PV Modules in the Conditions of the Turkish Economy, as Well as in the World

2.1. Renewable Energy Targets: The Case of Solar Energy

2.2. Renewable Energy in Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDC) or Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC)

2.3. Regulatory Policies

2.3.1. Feed-In Tariff (FiT)/Premium Payment

2.3.2. Electric Utility Quota Obligation/Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS)

2.3.3. Net Metering

2.3.4. Heat Obligation/Mandate

2.3.5. Tradable REC

2.3.6. Tendering

2.4. Fiscal Incentives and Public Financing

2.4.1. Investment or Production Tax Credits

2.4.2. Reductions in Sales, Energy, CO2, VAT, or Other Taxes

2.4.3. Energy Production Payment

2.4.4. Public Investment, Loans, Grants, Capital Subsidies, or Rebates

2.5. The Current Situation of the PV Modules Market in Türkiye and Eskisehir

2.6. The Role of Local Governments and Their Effects on Cities

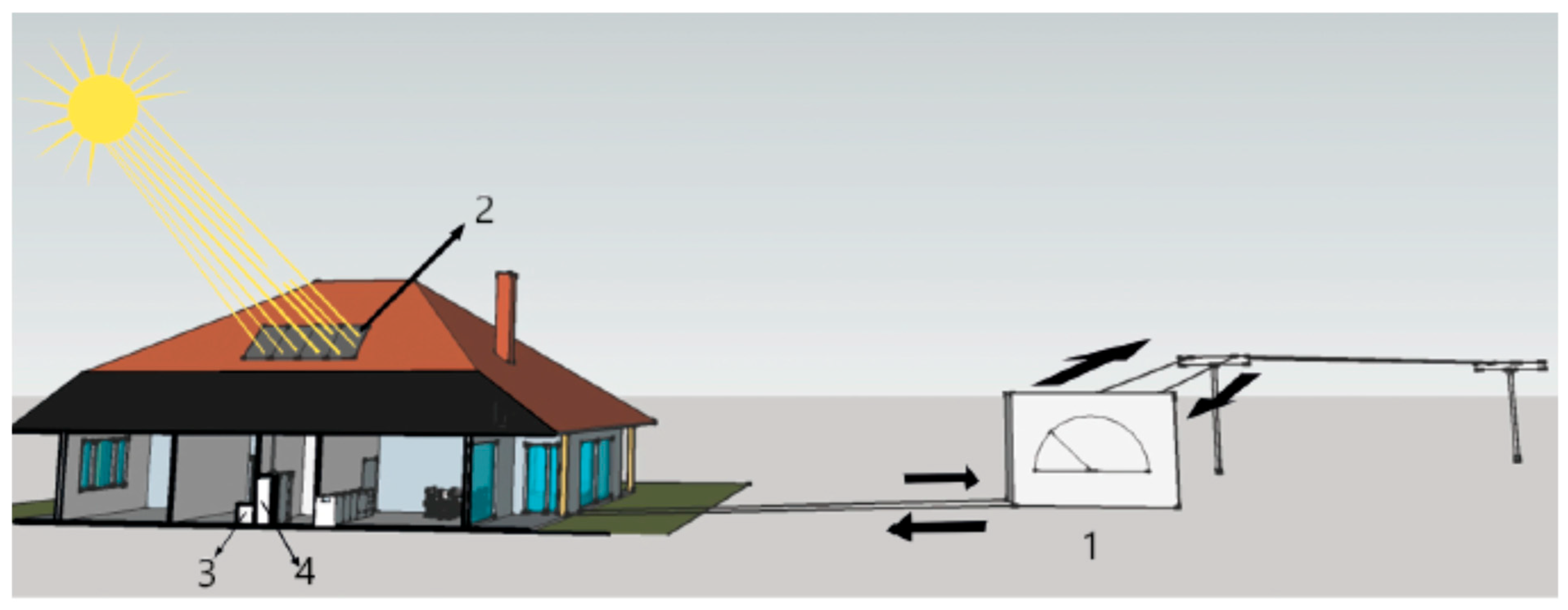

2.7. Technical Details and Financial Issues About PV Modules

3. Methodology: A Life-Cycle Cost Analysis with the Survey and Institutional Data

3.1. The Obtained Data from the Survey, Various Sources, Restrictions, and Assumptions for the Variables

3.2. Methods: Time Versus Money Dimension

3.2.1. Cost of PV Modules

- Cp: Total cost of installed PV equipment (€)

- Ca: Total area-dependent costs (€/m2)

- Ap: Panel area (m2)

- Ce: Total cost of PV equipment, which is independent of panel area (€).

- Yc: Yearly cost

- Fe: Fuel expense

- Mp: Mortgage payment

- Mi: Maintenance and insurance

- PEC: Parasitic energy costs

- PT: Property taxes

- ITS: Income tax savings.

3.2.2. Design for the Lowest Cost

3.3. Economic Approaches for Optimal Design

3.3.1. Least Cost Solar Energy

3.3.2. Life-Cycle Cost (LCC)

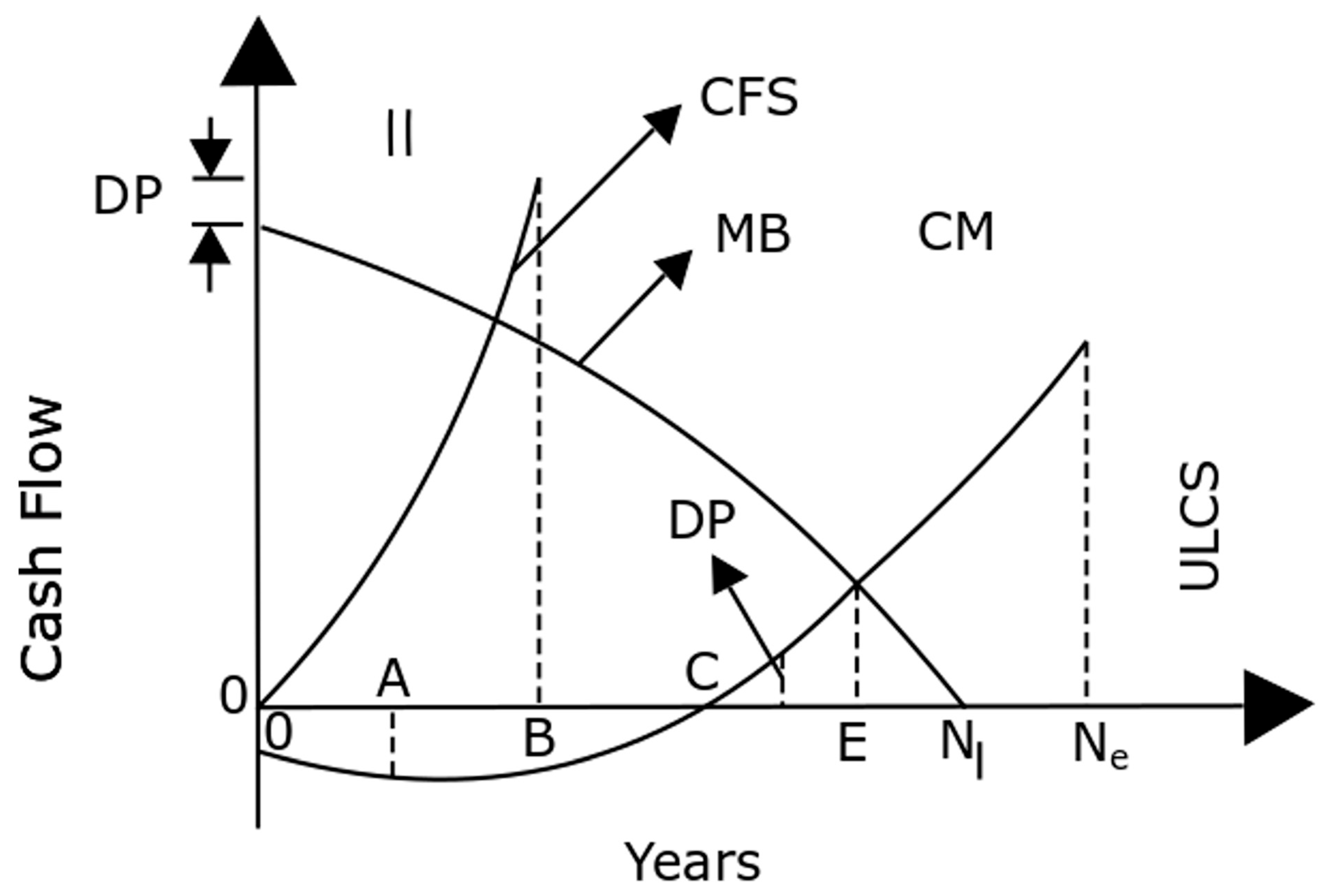

3.3.3. Life-Cycle Savings (LCS) (Net Present Worth)

3.3.4. Annualized Life-Cycle Cost (ALCC)

3.3.5. Payback Time

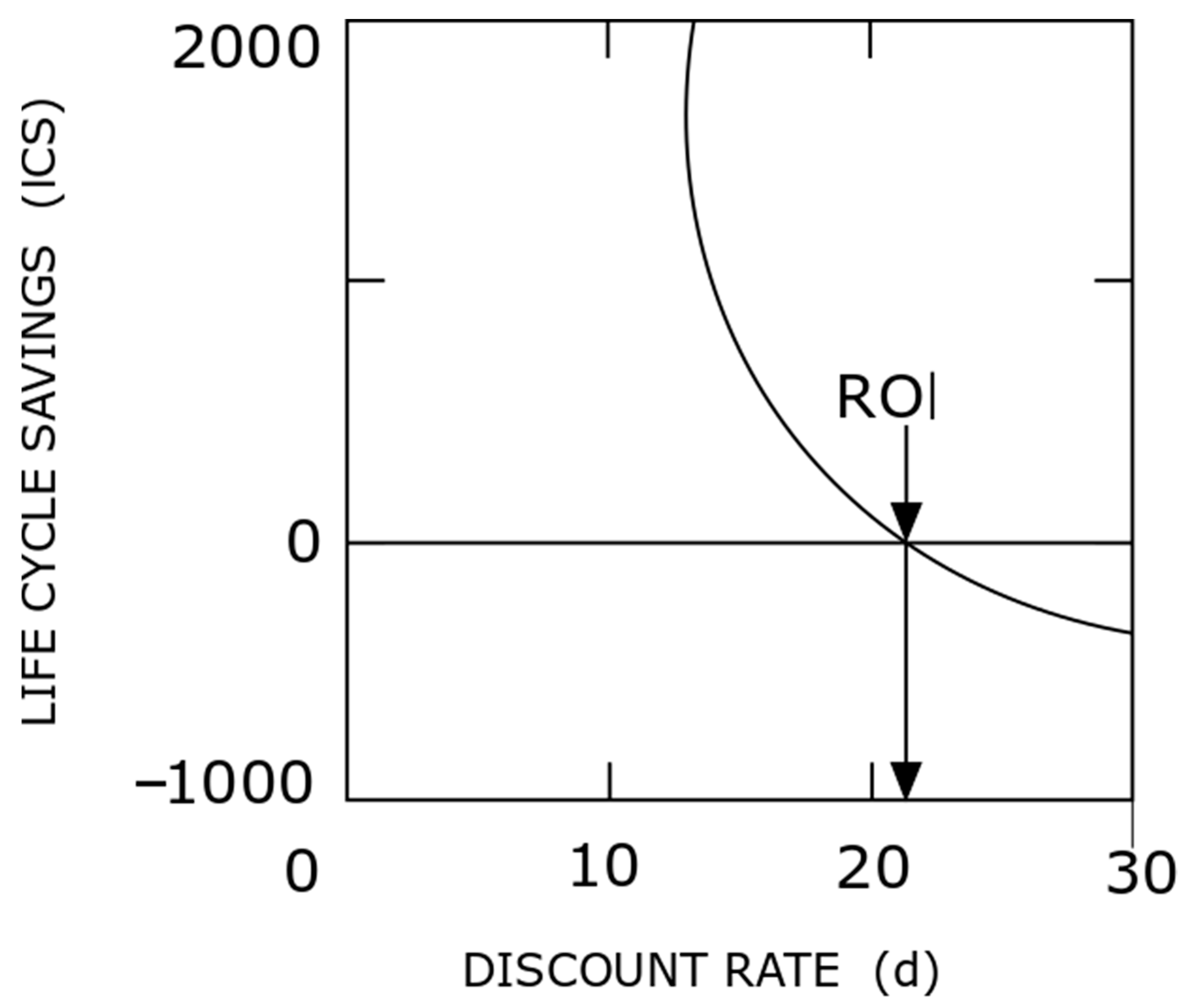

3.3.6. Return on Investment (ROI)

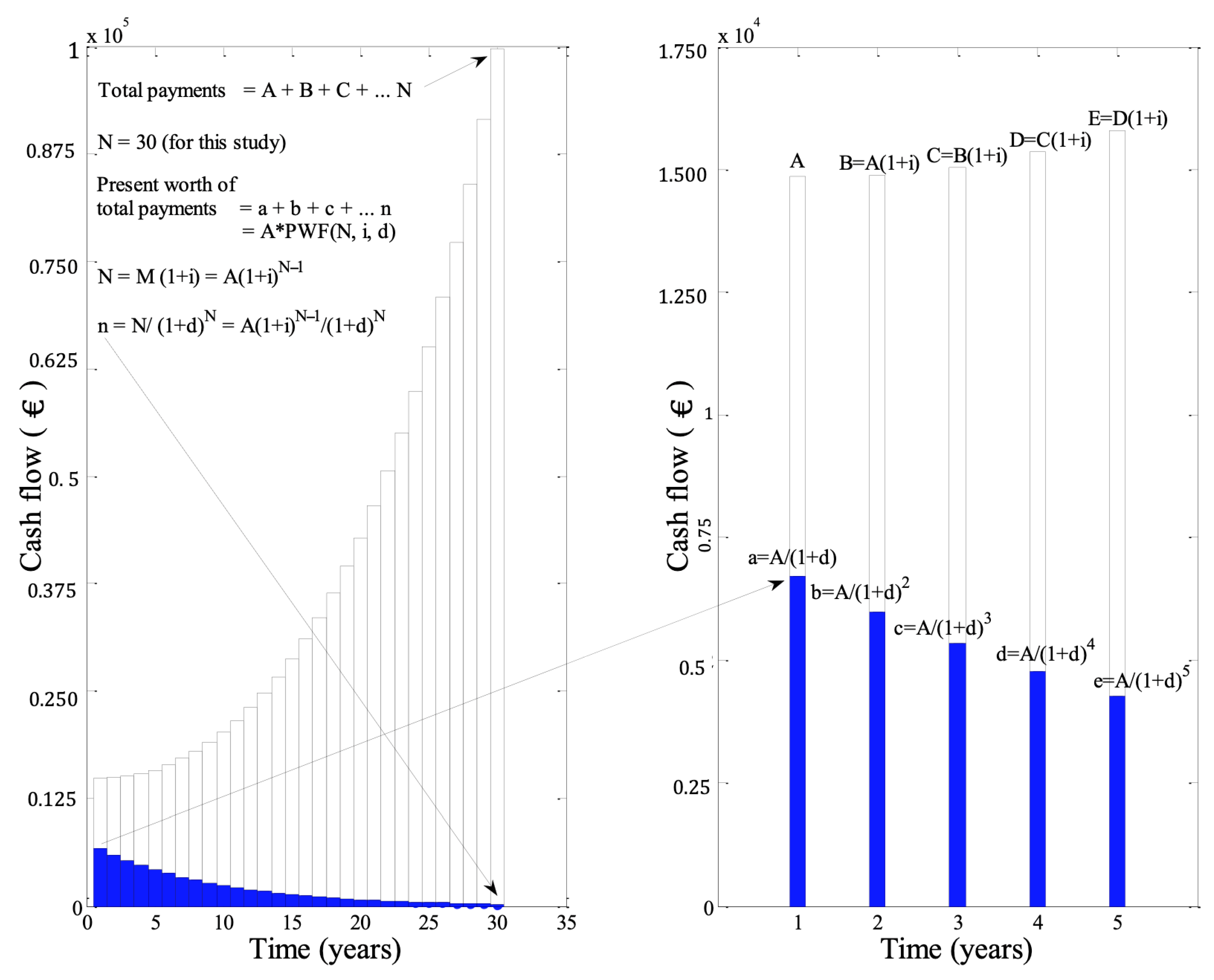

3.4. Discounting Factors and Inflation Rates

3.5. The Definition and Use of “Present-Worth Factor”

3.6. Life-Cycle Savings Method for Practical Applications

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.2. Application of Life-Cycle Saving Methods in Eskisehir’s Economy

4.3. A Critical Discussion: Combination of Solar and Conventional Energy Systems by Considering Future Savings or Costs in the Financial Conditions in the City of Eskisehir

4.4. Evaluation of Results for Different Scenarios

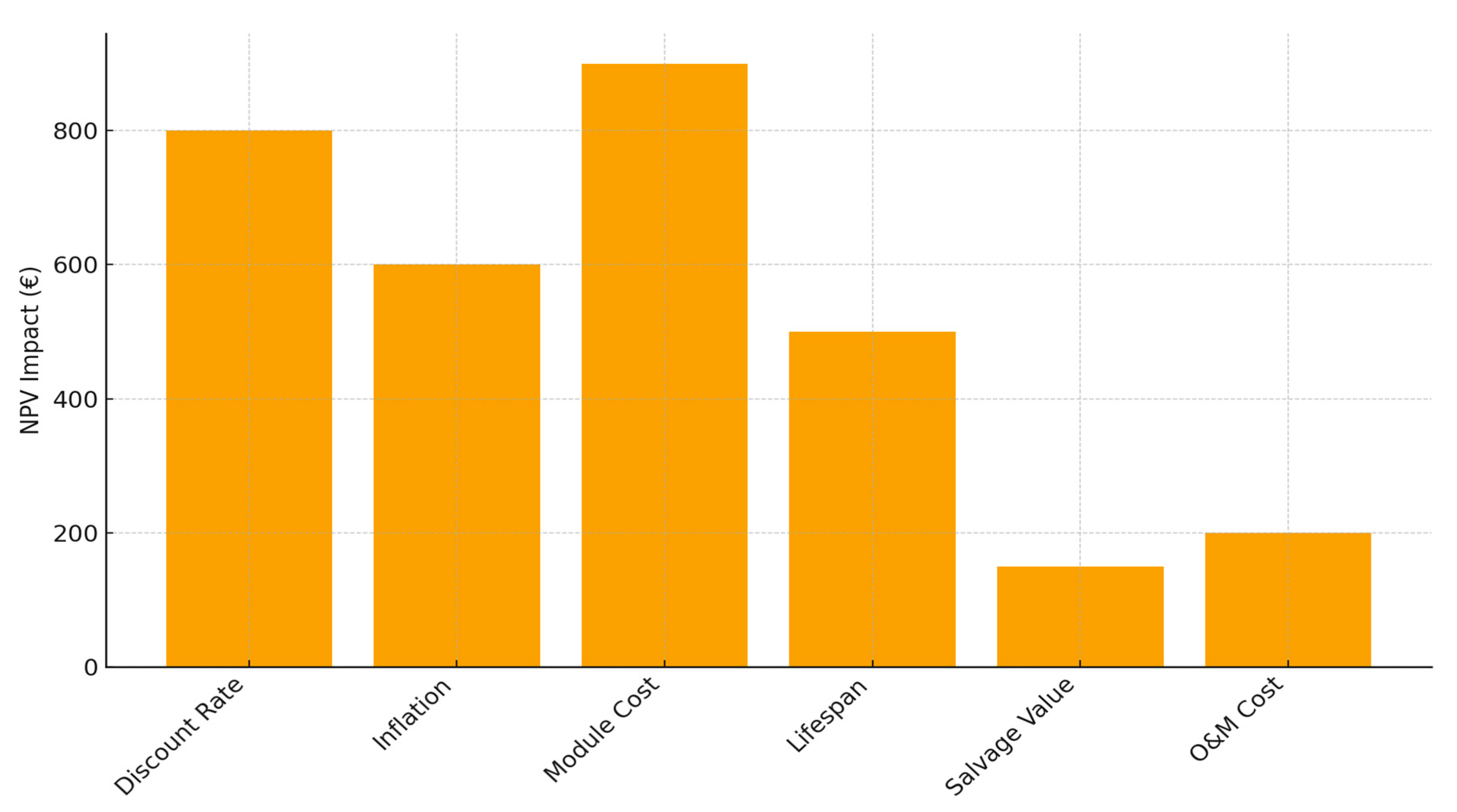

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis and Robustness Check

4.6. PV Performance Degradation

4.7. System Boundaries

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | Initial payment or cost |

| ALCC | Annualized Life-Cycle Cost |

| ALCS | Annualized Life-Cycle Savings |

| Ap | Panel area (m2) |

| BAU | Business-as-Usual |

| Ca | Total area-dependent costs (€/m2) |

| CBRT | Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye |

| Ce | Total cost of PV equipment which is independent of panel area (€) |

| CN | Cost value at Nth period |

| Cp | Total cost of installed PV equipment (€) |

| d | Discount rate |

| ECREEE | ECOWAS Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency |

| EFgrid | Grid emission factor |

| EPBT | Energy Payback Time |

| EPV | Electricity generated by the PV system |

| Fe | Fuel expense |

| FiPs | Feed-in Premiums |

| FiTs | Feed-in Tariffs |

| GHI | Global Horizontal Irradiation |

| i | Inflation rate |

| INDC | Intended Nationally Determined Contribution |

| ITS | Income tax savings |

| LCCA | Life-Cycle Cost Analysis |

| LCS | Life-Cycle Savings |

| m | Mortgage interest rate |

| M | Initial mortgage principle |

| M | Mortgage principle |

| Mi | Maintenance and insurance |

| Mp | Mortgage payment |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| Ne | Term for economic analysis |

| NL | Period of mortgage |

| NL | Mortgage term |

| Nmin | Lesser of NL or Ne |

| NPV | Net present value |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| PEC | Parasitic energy costs |

| PPL | Periodic payment of a loan |

| PT | Property taxes |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PVGIS | Photovoltaic Geographical Information System |

| PWF | Present-worth factor |

| PWN | Present worth of the Nth payment |

| REC | Renewable Energy Certificate |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| RPS | Renewable Portfolio Standard |

| TurkStat | Turkish Statistical Institute |

| TÜİK | Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu |

| VAT | Value-Added Tax |

| Yc | Yearly cost |

Appendix A

- Note 1:

- For 1 kW/h of energy, 6 modules are needed. Since 1 panel (180 W) is 1.58 m × 0.808 m dimensions and 1.27664 m2 area, a 6-module area is equal to (i.e., 6 × 1.27664 m2 = 7.7 m2) 7.7 m2. The price of this PV module, which has modules and the necessary equipment, is €2000. A 1 m2 PV module price is (i.e., from; (€2000 × 1)/7.7 m2 = €256.7 ≈ €260) €260. The 3 kW PV module area is 23.1 m2 (i.e., 7.7 m2 × 3 = 23.1 m2). Since a 1 kW system needs €250 maintenance cost 3 kW system needs (i.e., from; €250 × 3 = €750) €750 maintenance cost and since 1 kW system needs €200 inverter cost, 3 kW system needs (i.e., €200 × 3 = €600) €600 inverter cost. Thus, according to Equation (1), the total cost of equipment is approximately €7500 (i.e., €260 × 23.1 + (€750 + €600) = €7356 ≈ €7500).

- Note 2:

- PW15= €250 × (1 + 0.09)14/(1 + 0.10)15 ≈ €200

- Note 3:

- From Equation (13),

- PW = €250 × (1/(0.10 − 0.09)) × (1 − (1.09/1.10)30) ≈ €5991.25

- So, the present worth of the 30-year series is €5991.25.

- Note 4:

- €6375/PWF(30, 0, 0.10) ≈ €6375/9.43 ≈ €678.25

- Note 5:

- One should remember that the interest charge varies over time, because the mortgage payment includes both principal and interest. For our example, the interest payment for the first year is (i.e., 0.1 × €6375 = €637.5) €637.5. The annual payment is €678.25; thus, the principal payment is reduced by (i.e., €678.25 − €637.5 = €40.75) €40.75 to (i.e., €6334.25 × 0.10 = €633.425 ≈ €633.5) €633.5 and the principal payment is reduced by (i.e., €678.25 − €633.5 = €44.75) €44.75 to (i.e., €6334.25 − €44.75 = €6289.5) €6289.5. These are indicated in the following Table 2 (to the nearest €).

- Note 6:

- Here NL = Ne = 30 years, m = 0.1, d = 0.1, Nmin = Lesser of NL or Ne, M = €6375, PWF(Nmin, 0, d) → PWF(30, 0, 0.1) ≈ 9.4, PWF(NL, 0, m) → PWF(30, 0, 0.1) ≈ 9.4, PWF(Nmin, m, d) → PWF(30, 0.1, 0.1) ≈ 27.3.

- PWint = €6375 × → €6375 × [0.83] ≈ €5291.25

- Note that, while the worth of the interest payments is €5283.25 in Table 2, it is algebraically found as €5291.25. These two values are very close numerically. We can accept that the worth of the interest payment is around €5250. However, the sensitivity of digits, in other words, following the nearest first digit logic, creates this small difference!

- Note 7:

- year 1:

- Interest = 0.10 × €6750 = €675

- Principal payment = €715.75 − €675 = €40.75

- Principal balance = €6750 − €40.75 = €6709.25

- Tax savings = 0.45 × (€675 + €41.75) ≈ €322.5

- year 2:

- Interest = 0.10 × €6709.25 ≈ €671

- Principal payment = €715.75 − €671 = €44.75

- Principal balance = €6709.25 − €44.75 = €6664.5

- Tax savings = 0.45 × (€671 + €41.75 × (1.07)1 ≈ €322

References

- Chang, Z.; Jia, K.; Han, T.; Wei, Y.-M. Towards more reliable photovoltaic energy conversion systems: A weakly-supervised learning perspective on anomaly detection. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 316, 118845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Wan, Q.; Ming, J.; Shuai, C. Energy services for solar PV projects: Exploring the accessibility and affordability of clean energy for rural China. Energy 2024, 299, 131442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinna, P.; Laís, V.; Fernando, O.R.P.; Ricardo, R. Circular solar economy: PV modules decision-making framework for reuse. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Patel, M.K. Effect of tariffs on the performance and economic benefits of PV-coupled battery systems. Appl. Energy 2016, 164, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Liu, J.; Lin, X.; Li, M.; Kobashi, T. Assessing urban rooftop PV economics for regional deployment by integrating local socioeconomic, technological, and policy conditions. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.J.J. Virtuous cycle of solar photovoltaic development in new regions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayir Ervural, B.; Zaim, S.; Demirel, O.F.; Aydin, Z.; Delen, D. An ANP and fuzzy TOPSIS-based SWOT analysis for Turkey’s energy planning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1538–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, I.; Sari, R. The role of feed-in tariffs in emission mitigation: Turkish case. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agdas, D.; Barooah, P. On the economics of rooftop solar PV adoption. Energy Policy 2023, 178, 113611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, S.R.; Yousaf, H.; Irfan, M.; Rajala, A. Solar PV adoption at household level: Insights based on a systematic literature review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 50, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinta, A.A.; Sylla, A.Y.; Lankouande, E. Solar PV adoption in rural Burkina Faso. Energy 2023, 278, 127762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshurafa, A.M.; Hasanov, F.J.; Hunt, L.C. Macroeconomic, energy, and emission effects of solar PV deployment at utility and distributed scales in Saudi Arabia. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, F.; Aboagye, B.; Amo-Boateng, M.; Gyamfi, S.; Effah-Donyina, E. Economic evaluation of solar PV electricity prosumption in Ghana. Sol. Compass 2023, 5, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddari, N.; Derkyi, N.S.A.; Peprah, F. Towards sustainable and affordable energy for isolated communities: A technical and economic comparative assessment of grid and solar PV supply for Kyiriboja, Ghana. Sol. Compass 2024, 10, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Ruiz, R.; Martín-Martínez, S.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Ramírez, F.J.; Gómez-Lázaro, E. Solar PV power plant revamping: Technical and economic analysis of different alternatives for a Spanish case. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, L.F. Technocratic, techno-economic, and reactive: How media and parliamentary discourses on solar PV in Switzerland have formed over five decades and are shaping the future. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 108, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, H.A.; Simsek, N. Recent incentives for renewable energy in Turkey. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylu, O.B.; Turel, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Radulescu, M. Evaluating the impacts of renewable energy action plans: A synthetic control approach to the Turkish case. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Renewables 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2024 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Dawn, S.; Tiwari, P.K.; Goswami, A.K.; Mishra, M.K. Recent developments of solar energy in India: Perspectives, strategies and future goals. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ozoegwu, C.G.; Mgbemene, C.A.; Ozor, P.A. The status of solar energy integration and policy in Nigeria. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-B.; Yu, J.; Ma, L.; Luo, F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Q.; Xu, L. A study on solving the production process problems of the photovoltaic cell industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3546–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K.P.; Collier, J.M.; Ellingson, R.J.; Apul, D.S. Energy payback time (EPBT) and energy return on energy invested (EROI) of solar photovoltaic systems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.M.; Mateus, R.; Marques, L.; Ramos, M.; Almeida, M. Contribution of the solar systems to the nZEB and ZEB design concept in Portugal—Energy, economics and environmental life cycle analysis. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 156, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, R.; Doluweera, G.; Bergerson, J. Internalizing land use impacts for life cycle cost analysis of energy systems: A case of California’s photovoltaic implementation. Appl. Energy 2014, 116, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, D.L.; Muñoz-Cerón, E.; Ferrer-Rodríguez, J.P.; Nofuentes, G. Evolution of the cost and economic profitability of grid-connected PV investments in Spain: Long-term review according to the different regulatory frameworks approved. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo, H.F.; Udaeta, M.E.M.; Veiga Gimenes, A.L.; Grimoni, J.A.B. Assessment of photovoltaic distributed generation—Issues of grid connected systems through the consumer side applied to a case study of Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagani, A.; Mihelis, J.; Dedoussis, V. Techno-economic analysis and life-cycle environmental impacts of small-scale building-integrated PV systems in Greece. Energy Build. 2017, 139, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Le, K.N.; Zeng, S.X.; Wang, X.; Illankoon, I.M.C.S. Regenerative practice of using photovoltaic solar systems for residential dwellings: An empirical study in Australia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, N.I.; Dahlan, N.Y.; Hussin, M.Z. Optimizing solar PV investments: A comprehensive decision-making index using CRITIC and TOPSIS. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 49, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.M.; Gupta, R.P.; Mathew, M.; Jayakumar, A.; Singh, N.K. Performance, energy loss, and degradation prediction of roof-integrated crystalline solar PV system installed in Northern India. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 13, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acikgoz, F.; Yorulmaz, O. Renewable energy adoption among Türkiye’s future generation: What influences their intentions? Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 80, 101467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, B.; Gokcol, C. Impacts of the renewable energy law on the developments of wind energy in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, B.; Azapagic, A. Renewable electricity in Turkey: Life cycle environmental impacts. Renew. Energy 2016, 89, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi-Sahzabi, A.; Unlu-Yucesoy, E.; Sasaki, K.; Yuosefi, H.; Widiatmojo, A.; Sugai, Y. Turkish challenges for low-carbon society: Current status, government policies and social acceptance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.; Malandrino, O.; Supino, S.; Testa, M.; Lucchetti, M.C. Management of end-of-life photovoltaic panels as a step towards a circular economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2934–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tükenmez, M.; Demireli, E. Renewable energy policy in Turkey with the new legal regulations. Renew. Energy 2012, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topkaya, S.O. A discussion on recent developments in Turkey’s emerging solar power market. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3754–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozen, M. Renewable Energy Support Mechanism in Turkey: Financial Analysis and Recommendations to Policymakers. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2014, 4, 274–287. [Google Scholar]

- Basaran, S.T.; Dogru, A.O.; Balcik, F.B.; Ulugtekin, N.N.; Goksel, C.; Sozen, S. Assessment of renewable energy potential and policy in Turkey—Toward the acquisition period in European Union. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 46, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizamir, S.; de Véricourt, F.; Sun, P. Efficient Feed-In-Tariff Policies for Renewable Energy Technologies. Oper. Res. 2016, 64, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.R.; Easter, S.B.; Murphy-Mariscal, M.L.; Maestre, F.T.; Tavassoli, M.; Allen, E.B.; Barrows, C.W.; Belnap, J.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Ravi, S.; et al. Environmental impacts of utility-scale solar energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, H.; Trigoso, F.B.M.; Cavalcanti, J.A.M. Review of distributed generation with photovoltaic grid connected systems in Brazil: Challenges and prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punda, L.; Capuder, T.; Pandžić, H.; Delimar, M. Integration of renewable energy sources in southeast Europe: A review of incentive mechanisms and feasibility of investments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudisca, S.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Sgroi, F.; Testa, R.; Squatrito, R. Economic analysis of PV systems on buildings in Sicilian farms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Desideri, U. Do feed-in tariffs drive PV cost or viceversa? Appl. Energy 2014, 135, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Sumita, U.; Islam, A.; Bedja, I. Importance of policy for energy system transformation: Diffusion of PV technology in Japan and Germany. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numbi, B.P.; Malinga, S.J. Optimal energy cost and economic analysis of a residential grid-interactive solar PV system- case of eThekwini municipality in South Africa. Appl. Energy 2017, 186, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, M.; Tavoni, M. Are renewable energy subsidies effective? Evidence from Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, U.; Ur Rashid, T.; Khosa, A.A.; Khalil, M.S.; Rashid, M. An overview of implemented renewable energy policy of Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koussa, D.S.; Koussa, M. A feasibility and cost benefit prospection of grid connected hybrid power system (wind–photovoltaic)—Case study: An Algerian coastal site. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Yuksel, Y.E. Energy structure of Turkey for sustainable development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigter, J.; Vidican, G. Cost and optimal feed-in tariff for small scale photovoltaic systems in China. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6989–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo-Romero, M.d.P.; Sánchez-Braza, A.; Salvador-Ponce, J.; Sánchez-Labrador, N. An overview of feed-in tariffs, premiums and tenders to promote electricity from biogas in the EU-28. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REN21. Renewables 2017 Global Status Report; REN21 Secretariat: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/GSR2017_Full-Report_English.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Menanteau, P.; Finon, D.; Lamy, M.-L. Prices versus quantities: Choosing policies for promoting the development of renewable energy. Energy Policy 2003, 31, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finon, D. Incentives to invest in liberalised electricity industries in the North and South. Differences in the need for suitable institutional arrangements. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, D.R. An energy pricing scheme for the diffusion of decentralized renewable technology investment in developing countries. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 4284–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janko, S.A.; Arnold, M.R.; Johnson, N.G. Implications of high-penetration renewables for ratepayers and utilities in the residential solar photovoltaic (PV) market. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comello, S.; Reichelstein, S. Cost competitiveness of residential solar PV: The impact of net metering restrictions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y. Pricing electricity from residential photovoltaic systems: A comparison of feed-in tariffs, net metering, and net purchase and sale. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 2678–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeroni, P.; Olivero, S.; Repetto, M. Economic perspective for PV under new Italian regulatory framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boero, R.; Backhaus, S.N.; Edwards, B.K. The microeconomics of residential photovoltaics: Tariffs, network operation and maintenance, and ancillary services in distribution-level electricity markets. Sol. Energy 2016, 140, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECREEE. ECOWAS Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (ECREEE); ECREEE: Praia, Cabo Verde, 2015; Available online: https://www.ecreee.org/2015/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Thapar, S.; Sharma, S.; Verma, A. Economic and environmental effectiveness of renewable energy policy instruments: Best practices from India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydehell, H.; Lantz, B.; Mignon, I.; Lindahl, J. The impact of solar PV subsidies on investment over time—The case of Sweden. Energy Econ. 2024, 133, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-W. Using a system dynamics model to assess the effects of capital subsidies and feed-in tariffs on solar PV installations. Appl. Energy 2012, 100, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, D.L.; Nofuentes, G.; Aguilera, J. The internal rate of return of photovoltaic grid-connected systems: A comprehensive sensitivity analysis. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, G.; Grimm, M.; Huppertz, M.; Langbein, J.; Peters, J. Are promotion programs needed to establish off-grid solar energy markets? Evidence from rural Burkina Faso. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, M. The role of renewables in increasing Turkey’s self-sufficiency in electrical energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2629–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Negro, S.O.; Hekkert, M.P.; Bi, K. How China became a leader in solar PV: An innovation system analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.L. Influence of local environmental, social, economic and political variables on the spatial distribution of residential solar PV arrays across the United States. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Sagner, G.; Mata-Torres, C.; Pino, A.; Escobar, R.A. Economic feasibility of residential and commercial PV technology: The Chilean case. Renew. Energy 2017, 111, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varun; Prakash, R.; Bhat, I.K. Energy, economics and environmental impacts of renewable energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2716–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Roy, B. Solar energy market developments in India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acaroğlu, H.; Baykul, M.C. Economic guideline about financial utilization of flat-plate solar collectors (FPSCs) for the consumer segment in the city of Eskisehir. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2045–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.A.; Case, K.E.; Pratt, D.B. Principles of Engineering Economic Analysis; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo, E.P.; Sullivan, W.G.; Canada, J.R. Engineering Economy; Macmillan: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, W.A.; Klein, S.A.; Duffie, J.A. Solar Heating Design, by the F-Chart Method; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, M.; Joshi, H.; Panda, S.K. Energy payback time and life-cycle cost analysis of building integrated photovoltaic thermal system influenced by adverse effect of shadow. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acaroğlu, H.; Baykul, M.C. Economic analysis of flat-plate solar collectors (FPSCs): A solution to the unemployment problem in the city of Eskisehir. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Y.; Mulyadi, M.S. Income tax incentives on renewable energy industry: Case of USA, China, and Indonesia. Bus. Rev. Camb. 2011, 17, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024; Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2024/Sep/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2023 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Meneguzzo, F.; Ciriminna, R.; Albanese, L.; Pagliaro, M. The great solar boom: A global perspective into the far reaching impact of an unexpected energy revolution. Energy Sci. Eng. 2015, 3, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortop, H.S. Awareness and Misconceptions of High School Students about Renewable Energy Resources and Applications: Turkey Case. Energy Educ. Sci. Technol. Part B Soc. Educ. Stud. 2012, 4, 1829–1840. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED558211 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Regulatory Policies | Fiscal Incentives and Public Financing | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Renewable energy targets | Renewable energy in INDC or NDC | Feed-in tariff/ premium payment | Electric utility quota obligation/RPS | Net metering | Transport obligation/mandate | Heat obligation/mandate | Tradable REC | Tendering | Investment or production tax credits | Reductions in sales, energy, CO2, VAT, or other taxes | Energy production payment | Public investment, loans, or grants, capital subsidies or rebates |

| Türkiye | O | O | R | O | H | O | |||||||

| O—existing national (could also include sub-national) R—Revised (one or more policies of this type) H—Tenders held in 2016, as in past years | |||||||||||||

| Year | Mortgage Payment | Remaining Principle | Interest Payment | Present Worth of Interest Payment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 678 | 6334 | 638 | 580 |

| 2 | 678 | 6290 | 634 | 524 |

| 3 | 678 | 6240 | 629 | 473 |

| 4 | 678 | 6186 | 624 | 426 |

| 5 | 678 | 6127 | 619 | 384 |

| 6 | 678 | 6061 | 613 | 346 |

| 7 | 678 | 5989 | 606 | 311 |

| 8 | 678 | 5910 | 599 | 280 |

| 9 | 678 | 5823 | 591 | 251 |

| 10 | 678 | 5727 | 582 | 225 |

| 11 | 678 | 5621 | 573 | 201 |

| 12 | 678 | 5505 | 562 | 179 |

| 13 | 678 | 5377 | 551 | 160 |

| 14 | 678 | 5237 | 538 | 142 |

| 15 | 678 | 5082 | 524 | 125 |

| 16 | 678 | 4912 | 508 | 111 |

| 17 | 678 | 4725 | 491 | 97 |

| 18 | 678 | 4520 | 473 | 85 |

| 19 | 678 | 4293 | 452 | 74 |

| 20 | 678 | 4045 | 429 | 64 |

| 21 | 678 | 3771 | 405 | 55 |

| 22 | 678 | 3470 | 377 | 46 |

| 23 | 678 | 3138 | 347 | 39 |

| 24 | 678 | 2774 | 314 | 32 |

| 25 | 678 | 2373 | 278 | 26 |

| 26 | 678 | 1932 | 237 | 20 |

| 27 | 678 | 1447 | 193 | 15 |

| 28 | 678 | 914 | 145 | 10 |

| 29 | 678 | 327 | 92 | 6 |

| 30 | 678 | −319 | 33 | 2 |

| The worth of the interest payments | 5283.25 | |||

| Year | Fuel (Natural Gas) Cost | Present Worth of Fuel (Natural Gas) Cost |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 468 | 426 |

| 2 | 510 | 422 |

| 3 | 556 | 418 |

| 4 | 606 | 414 |

| 5 | 661 | 410 |

| 6 | 720 | 407 |

| 7 | 785 | 403 |

| 8 | 856 | 399 |

| 9 | 933 | 396 |

| 10 | 1017 | 392 |

| 11 | 1108 | 388 |

| 12 | 1208 | 385 |

| 13 | 1316 | 381 |

| 14 | 1435 | 378 |

| 15 | 1564 | 375 |

| 16 | 1705 | 371 |

| 17 | 1858 | 368 |

| 18 | 2025 | 364 |

| 19 | 2208 | 361 |

| 20 | 2406 | 358 |

| 21 | 2623 | 355 |

| 22 | 2859 | 351 |

| 23 | 3116 | 348 |

| 24 | 3397 | 345 |

| 25 | 3703 | 342 |

| 26 | 4036 | 339 |

| 27 | 4399 | 336 |

| 28 | 4795 | 333 |

| 29 | 5226 | 330 |

| 30 | 5697 | 327 |

| The worth of fuel (natural gas) cost | 11,215.5 | |

| Year | Fuel (Natural Gas) Cost | Present Worth of Fuel (Natural Gas) Cost |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 468 | 438 |

| 2 | 506 | 442 |

| 3 | 546 | 446 |

| 4 | 590 | 450 |

| 5 | 637 | 454 |

| 6 | 688 | 458 |

| 7 | 722 | 450 |

| 8 | 758 | 441 |

| 9 | 796 | 433 |

| 10 | 836 | 425 |

| 11 | 878 | 417 |

| 12 | 922 | 409 |

| 13 | 968 | 402 |

| 14 | 1016 | 394 |

| 15 | 1067 | 387 |

| Total | 11,394.75 | 6443.5 |

| Years | Fuel Savings | Extra Mortgage Payment | Extra Insurance Maintenance Energy | Extra Property Tax | Income Tax Savings | Solar Savings | Present Worth of Solar Savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | - | - | - | −750 | −750 |

| 1 | 281 | −716 | −33 | −42 | 323 | −188 | −171 |

| 2 | 306 | −716 | −36 | −45 | 322 | −168 | −139 |

| 3 | 334 | −716 | −38 | −48 | 322 | −147 | −110 |

| 4 | 364 | −716 | −41 | −51 | 321 | −123 | −84 |

| 5 | 396 | −716 | −44 | −55 | 320 | −98 | −61 |

| 6 | 432 | −716 | −47 | −59 | 319 | −70 | −40 |

| 7 | 471 | −716 | −50 | −63 | 318 | −40 | −20 |

| 8 | 513 | −716 | −54 | −67 | 317 | −6 | −3 |

| 9 | 560 | −716 | −57 | −72 | 315 | 30 | 13 |

| 10 | 610 | −716 | −61 | −77 | 314 | 70 | 27 |

| 11 | 665 | −716 | −66 | −82 | 312 | 113 | 40 |

| 12 | 725 | −716 | −70 | −88 | 309 | 160 | 51 |

| 13 | 790 | −716 | −75 | −94 | 307 | 212 | 62 |

| 14 | 861 | −716 | −80 | −101 | 304 | 269 | 71 |

| 15 | 938 | −716 | −86 | −108 | 301 | 330 | 79 |

| 16 | 1023 | −716 | −92 | −115 | 297 | 398 | 87 |

| 17 | 1115 | −716 | −98 | −123 | 293 | 471 | 93 |

| 18 | 1215 | −716 | −105 | −132 | 289 | 551 | 99 |

| 19 | 1325 | −716 | −113 | −141 | 284 | 639 | 105 |

| 20 | 1444 | −716 | −120 | −151 | 278 | 735 | 109 |

| 21 | 1574 | −716 | −129 | −162 | 272 | 839 | 114 |

| 22 | 1715 | −716 | −138 | −173 | 264 | 953 | 117 |

| 23 | 1870 | −716 | −147 | −185 | 256 | 1078 | 120 |

| 24 | 2038 | −716 | −158 | −198 | 247 | 1214 | 123 |

| 25 | 2222 | −716 | −169 | −212 | 237 | 1362 | 126 |

| 26 | 2421 | −716 | −181 | −227 | 225 | 1524 | 128 |

| 27 | 2639 | −716 | −193 | −243 | 213 | 1701 | 130 |

| 28 | 2877 | −716 | −207 | −260 | 199 | 1894 | 131 |

| 29 | 3136 | −716 | −221 | −278 | 183 | 2104 | 133 |

| 30 | 3418 | −716 | −237 | −297 | 165 | 2334 | 134 |

| 30 | 3000 | 172 | |||||

| Total present worth of solar savings = | 883.75 | ||||||

| Scenario | Key Assumptions (Summary) | Scaling Factor | Present Worth of PV Benefits | Change in Initial Investment Cost | Estimated NPV (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worst-case | −10% annual PV yield; net-metering benefits reduced by 50%; −10% present-worth effect; +10% installation cost | 0.405 | €357.92 | +€750 | €−392.08 |

| Business-as-Usual (BAU) | Baseline policy and economic assumptions (original model) | 1.00 | €883.75 | €0 | €883.75 |

| Optimistic | +10% PV yield; +20% policy/environmental incentive effect; +5% discount-rate effect; −15% installation cost | 1.386 | €1224.88 | −€1125 | €2349.88 |

| Parameter | Variation Range | Low Case NPV (€) | Base Case NPV (€) | High Case NPV (€) | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discount Rate | 7–12% | 430 | 884 | 1560 | High |

| Inflation | 7–12% | 610 | 884 | 1480 | High |

| Module Cost Change | −20% to +10% | 230 | 884 | 1540 | High |

| System Lifespan | 25–35 years | 650 | 884 | 1130 | Medium |

| Salvage Value | 0–10% | 860 | 884 | 925 | Low |

| O&M Costs | ±30% | 760 | 884 | 1020 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acaroğlu, H.; Baykul, M.C.; Kara, Ö. A Life-Cycle Cost Analysis on Photovoltaic (PV) Modules for Türkiye: The Case of Eskisehir’s Solar Market Transactions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411023

Acaroğlu H, Baykul MC, Kara Ö. A Life-Cycle Cost Analysis on Photovoltaic (PV) Modules for Türkiye: The Case of Eskisehir’s Solar Market Transactions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411023

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcaroğlu, Hakan, Mevlana Celalettin Baykul, and Ömer Kara. 2025. "A Life-Cycle Cost Analysis on Photovoltaic (PV) Modules for Türkiye: The Case of Eskisehir’s Solar Market Transactions" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411023

APA StyleAcaroğlu, H., Baykul, M. C., & Kara, Ö. (2025). A Life-Cycle Cost Analysis on Photovoltaic (PV) Modules for Türkiye: The Case of Eskisehir’s Solar Market Transactions. Sustainability, 17(24), 11023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411023