Distribution of the Land Value Increment in the Context of Rural Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

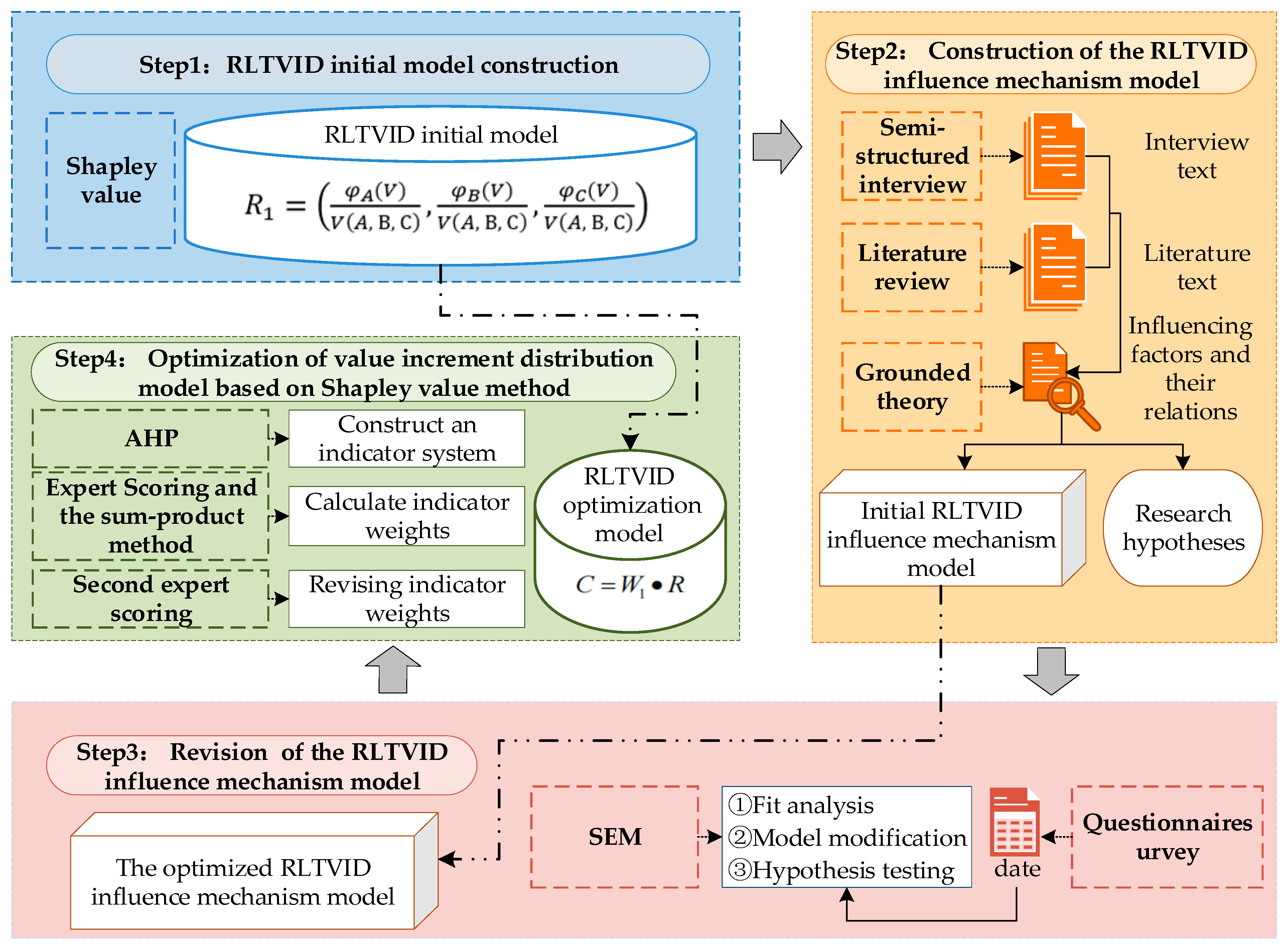

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Mechanism and Research Design

3.1.1. Theoretical Mechanism

- (1)

- Model Selection

- (2)

- Distribution Principles and Their Operationalization

3.1.2. Research Design

3.2. Study Area

3.3. Data Collection

4. Model Construction

4.1. RLTVID Initial Model Construction

- (1)

- S = {A}: Government participation alone. Since land ownership belongs to the village collective, the government cannot undertake the project without the collective’s cooperation. Therefore, the value increment V(A) = 0.

- (2)

- S = {B}: The village collective and villagers contribute land and labor, obtaining value increment V(B) through transfer, circulation, or self-operation.

- (3)

- S = {C}: Developer participation alone. Without the cooperation of the village collective and government support, the developer cannot obtain land use rights. Therefore, the value increment V(C) = 0.

- (4)

- S = {A, B}: The local government coordinates and collaborates with the village collective and villagers. The collective provides land for tourism development, while the government offers policy guidance and infrastructure support. The resulting value increment is denoted as V(A, B).

- (5)

- S = {A, C}: The local government cooperates with the investment developer. Without the participation of the land-owning village collective, land use rights cannot be obtained. Therefore, the land value increment V(A, C) = 0.

- (6)

- S = {B, C}: The village collective and villagers cooperate with the developer. The villagers and the collective provide land and labor, while the developer supplies capital and technology. Although government support is absent, cooperation between land and capital still takes place. Therefore, the land value increment is V(B, C).

- (7)

- S = {A, B, C}: Three-party cooperation. The government provides policy support; the villagers and the collective provide land; and the developer provides capital and technology. The land value increment is denoted as V(A, B, C).

4.2. Construction and Revision of the RLTVID Influence Mechanism Model

4.2.1. Identification of Influencing Factors for Value Increment Distribution

- (1)

- Open Coding Results

- (2)

- Axial Coding Results

- (3)

- Selective Coding Results

- (4)

- Saturation Testing

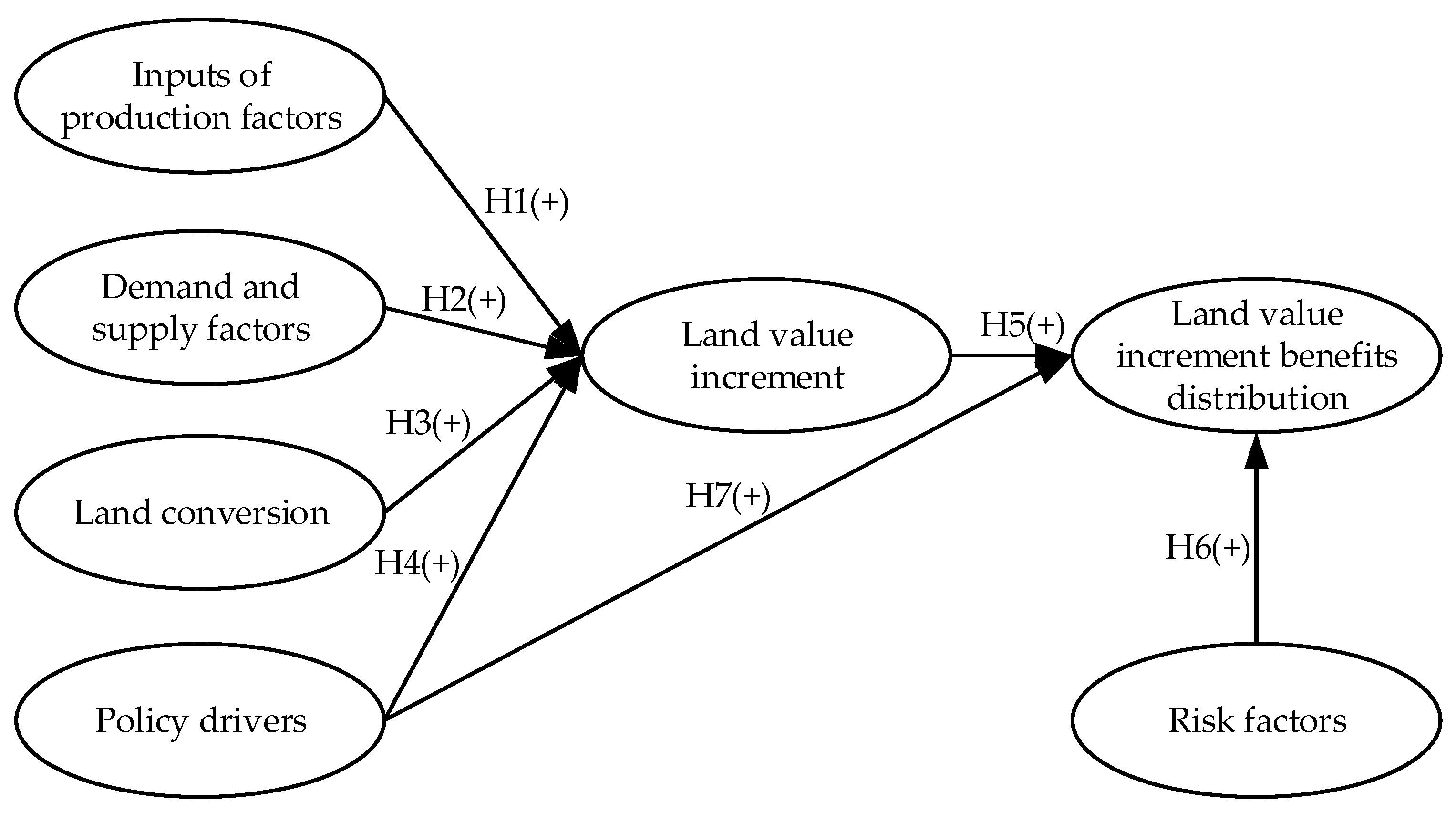

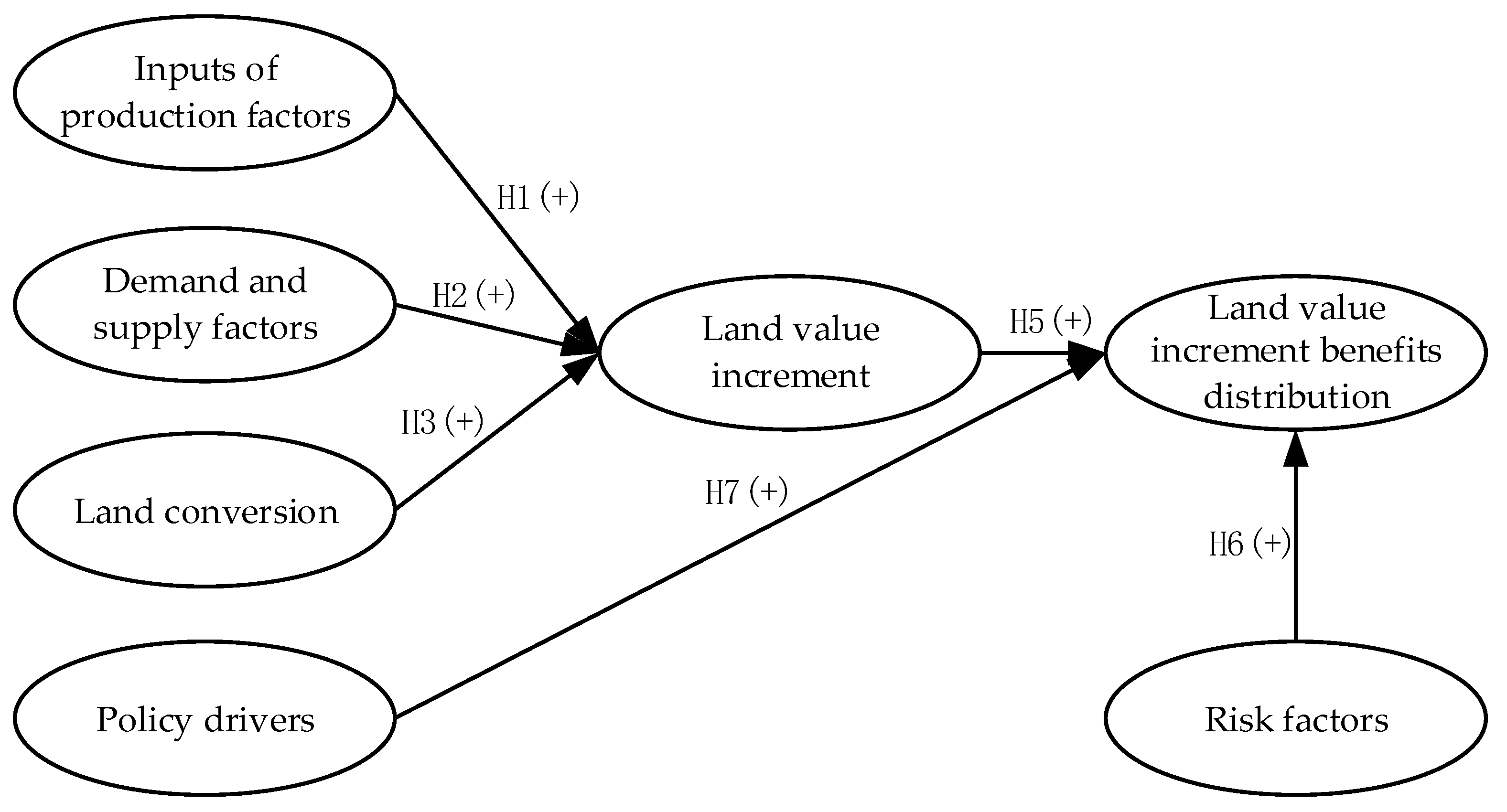

4.2.2. Construction of the Initial RLTVID Influence Mechanism Model and Research Hypotheses

4.2.3. Questionnaire Design

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Measurement Model Analysis

5.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.3. Structural Model Analysis

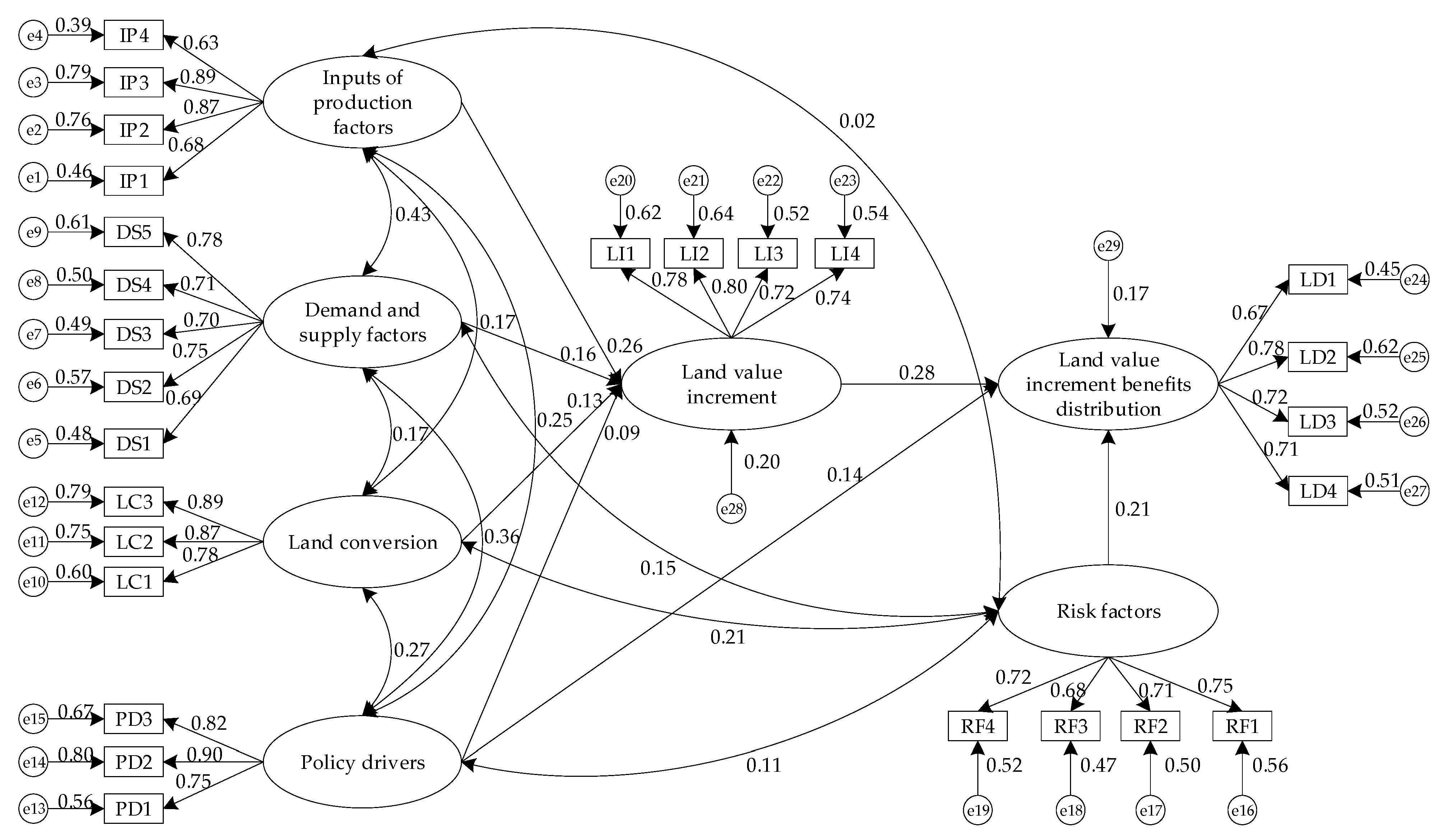

5.3.1. Initial Construction of the Structural Equation Model and Fit Analysis

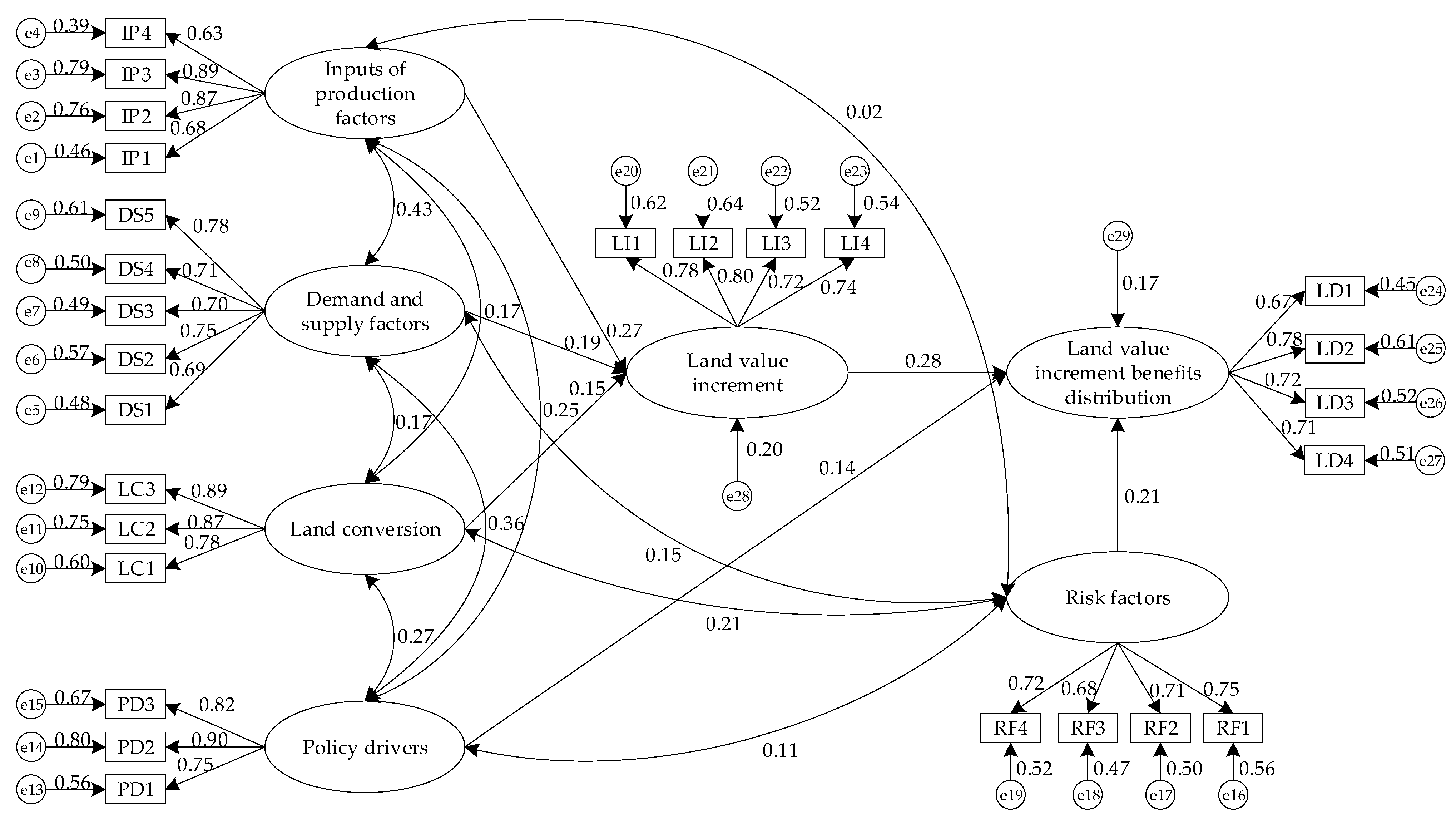

5.3.2. Model Modification

5.3.3. Hypothesis Testing

5.4. Optimization of Value Increment Distribution Model Based on Shapley Value Method

5.4.1. Weight Determination Based on AHP

- (1)

- Constructing the Hierarchical Structure Model

- (2)

- Constructing the Judgment Matrix

- (3)

- Calculation of Indicator Weights and Consistency Check

5.4.2. Calculation of Indicator Weights Using the Sum-Product Method

5.4.3. Determination of Indicator Threshold Values

5.4.4. Modification of the Value Increment Distribution Model

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.1.1. Further Discussion of Results

6.1.2. Theoretical Implications

6.1.3. Managerial Implications

6.1.4. Limitations and Future Research Prospects

- (1)

- Limited generalizability due to a single case study. This research selected only Zhongyuan Township as the study area. While representative, China’s vast territory exhibits significant differences in regional economic development levels, land policy systems, and rural tourism models; thus, the generalizability of the findings needs further verification with broader samples. Future research should test the model’s stability and transferability by applying it to multiple case studies across diverse contexts within and beyond China, which would also reveal how varying institutional and cultural settings influence the distribution outcomes.

- (2)

- Inability to capture dynamic processes. The reliance on cross-sectional data means this study provides a static snapshot, unable to observe how distribution relationships and stakeholder perceptions evolve as a tourism destination matures. Future research would benefit from longitudinal studies tracking the dynamics of land value distribution over time.

- (3)

- Potential for methodological biases. Firstly, the face-to-face interview approach, though necessary for our respondent pool, carries a risk of social desirability bias. Future work could mitigate this by employing mixed methods, such as anonymous surveys combined with qualitative interviews. Secondly, the reliance on the AHP for weight determination introduces an element of subjectivity. Enhancing this with objective data, like regional economic indicators or historical land value data, would improve the model’s robustness.

- (4)

- Simplified treatment of complex factors. The model’s quantification of policy drivers is relatively simplified, whereas actual policy implementation is complex. Future research could combine more granular policy data and in-depth field investigations to deeply analyze the mechanism of policy in value increment distribution and further optimize the model.

6.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interview Topics | Interview Questions |

|---|---|

| Perceptions regarding the development of rural tourism in rural areas | In your opinion, what specific contributions and efforts have the government, villagers, and investor-developers, respectively, made towards the development of rural tourism? |

| What positive and negative impacts do you believe the development of rural tourism in rural areas has brought to local regional development, individual villagers, village collectives, and the government? | |

| Perceptions regarding rural land transfer for developing rural tourism | To date, how much land in Zhongyuan Township has been transferred for developing rural tourism, and what are the specific processes involved in this land transfer? |

| What positive impacts do you think the transfer of rural land for developing rural tourism has had on individuals and local social development? | |

| What risks and pressures do you believe the local government, villagers, and developers need to bear during the process of transferring rural land for tourism development? | |

| Perceptions regarding the development of rural tourism in rural areas | In your view, what factors contribute to the generation of land value increment during the development of rural tourism? |

| How is the value increment generated by rural tourism development currently distributed? Do you consider this distribution model and its outcomes to be reasonable? | |

| Whose interests do you think should be prioritized in the distribution of value increment from rural tourism development, and how should the interests of all parties be balanced? | |

| What other important influencing factors do you believe should be considered to achieve a fair distribution of land value increment? |

References

- Qi, P.W.; Sun, Y.Y.; Chen, P. Evaluation of Farmers’ Livelihood Vulnerability in Border Rural Tourism Destination and Its Influencing Factors-Take Tumen City, Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, Jilin Province, as an Example. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zou, Y.G.; Chai, S.S.; Chen, P.Y. The Evolution Mechanism of Implicit Conflict in Rural Tourism Communities: From the Perspective of Community Residents. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 52–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.B.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.Y. The Spatial Characteristics and Formation Mechanism of Conflicts in Tourism Community Under the Background of Landscape-village Integration: A Case Study of Dong Village in Zhaoxing. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 216–224. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Liu, L. Evolution Mechanism of Tourism Islanding Effect: A Case Study of Puzhehei Tourist Attraction. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 41, 22–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.F.; Cao, H. Tourism Development and Rural Land Transfer-Out: Evidence from China Family Panel Studies. Land 2024, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Dai, M.L.; Fan, D.X.F. Cooperation or Confrontation? Exploring Stakeholder Relationships in Rural Tourism Land Expropriation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1841–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Legal System for the Value-Added Income Distribution of Rural Homesteads from the Perspective of Common Prosperity—Taking the Theory of Sharing Land Development Rights as an Analytical Framework. Henan Soc. Sci. 2024, 32, 85–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.B.; Liu, X.M. Discussion on Value-added Income Distribution of Collective Operational Construction Land’s Entering the Market: Taking the Pilot Reform of Rural Land System as Example. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2018, 40, 41–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.M.; Yuan, S.F.; Li, S.N.; Xia, H. Study on Incremental Revenue Distribution of Rural Residential Land based on Land Development Right and Function Loss: Taking the “Land Coupons” in Yiwu as an Example. China Land Sci. 2017, 31, 37–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Dong, Q.Y.; Li, C.J. Research on Realization Mechanism of Land Value-Added Benefit Distribution Justice in Rural Homestead Disputes in China-Based on the Perspective of Judicial Governance. Land 2023, 12, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kan, X.; Jiang, X.R. Imbalance and Balance: The Distribution of Land Value-added Benefits in Postmining Land Use. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 13, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.L.; Huang, S.S.; Huang, Y.C. Rural Tourism Development in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.C.; Zhao, M.F.; Ge, Q.S.; Kong, Q.Q. Changes in Land Use of a Village Driven by over 25 Years of Tourism: The Case of Gougezhuang Village, China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.T.; Nyaupane, G.P. Protected areas, tourism and community livelihoods linkages: A comprehensive analysis approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.F. The Logic of Land Rights: Where Is China’s Rural Land System Heading; China University of Political Science & Law Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.M. On the Reform of China’s Land System; China Financial & Economic Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z.X. A Study on the Operation Mechanism and Social Effects of Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives in China; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. The Practice and Dilemmas of “Profit from Appreciation to the Public”: From Ideal to Reality. Sociol. Stud. 2021, 36, 23–46+225–226. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.G. On the Principle of Value Added Income Distribution in Real Estate Land. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2018, 3, 32–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; He, M.Y.; Gao, Y. An Empirical Study on Land Revenue Distribution in Agricultural Land Conversion in China: A Sampling Survey Analysis Based on Kunshan, Tongcheng, and Xindu. J. Manag. World 2006, 10, 62–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y. On the Distribution of Revenue from the Market Entry and Circulation of Rural Collective Business Construction Land. Rural. Econ. 2014, 10, 3–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.R.; Zhu, D.L. A Spatial and Temporal Analysis on Land Incremental Values Coupled with Land Rights in China. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B.; Zhou, Y.P. The Marketization of Rural Collective Construction Land in Northeastern China: The Mechanism Exploration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.X.; Dries, L.; Heijman, W.; Zhang, A.L. Land Value Creation and Benefit Distribution in the Process of Rural-urban Land Conversion: A Case Study in Wuhan City, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 109, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Xu, S.G.; Gao, J. Value-added Income Distribution of Homestead Exit Compensation in Major Grain Producing Areas in Northeast China from the Perspective of Land Development Right. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 1883–1891. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Shen, K.J. Just Compensation and Distribution of Land Added Value in Eminent Domain. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 19, 142–149. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.F.; Thill, J.C.; Feng, C.C.; Zhu, G.Y. Land Wealth Generation and Distribution in the Process of Land Expropriation and Development in Beijing, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. The Current Status and Causes of Farmers’ Sharing in Land Appreciation Benefits in Rural Tourism Development. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 72–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J. Land Value Increment Distribution of Collective Operational Construction Land: Summary of Pilot Projects and Design of System. Law Sci. Mag. 2019, 40, 45–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wan, J. Distribution of Rural Land Appreciation Gains from the Perspective of “Empowerment and Restriction”: Evolutionary Trajectory and Basic Experience. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2023, 335, 120–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, Y.F.; Li, S.J. Empirical Study of Distribution of Incremental Land Revenue: Case Study of Jiutai District in Northeast China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 05021037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Hong, K.R.; Li, H. Transfer of Land Use Rights in Rural China and Farmers’ Utility: How to Select an Optimal Payment Mode of Land Increment Income. Land 2021, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Y. Tourism—Based Community: A New Perspective of the Justice of the Distribution of Tourism—Based Interests in Traditional Villages. J. Yunnan Minzu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 38, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solan, E.; Vieille, N. Stochastic Games. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13743–13746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.W.; Guo, S.F.; Zeng, L.; Li, X.Y. Formation Mechanisms of Rural Summer Health Destination Loyalty: Exploration and Comparison of Low- and High-Aged Elderly Leisure Vacation Tourists. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Tao, Z.M.; Liu, J.M.; Tao, H.; Lu, M.; Song, H.F. Spatial Characteristics of Rural Tourism Employment Promotion in Mountainous Areas. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 153–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.W.; Huang, X.; Yue, H. The High-quality Development of Rural Tourism: Connotative Features, Key Issues and Countermeasures. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2020, 8, 27–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Valeri, M.; Shekhar. Understanding the Relationship Among Factors Influencing Rural Tourism: A Hierarchical Approach. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2022, 35, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in Rural Tourism: Do Lifestyle Motivations Contribute to Management Practices that Enhance Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.L.; Cheng, L. Tourism-driven Rural Spatial Restructuring in the Metropolitan Fringe: An Empirical Observation. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, W.; Wu, Z.J.; Su, C.H.; Chen, M.H. Understanding Farm Households’ Participation in Nong Jia Le in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Ye, Y. Rural Tourism, Economic Growth, and Environmental Sustainability: Empirical Evidence Based on County-Level Data in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.J. Performance Evaluation of Rural Tourism Land Transfer Based on DEA Model. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech 2017, 28, 347–351. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Y.; Hu, Y.J.; Wang, Q.X.; Chen, Y.W.; He, Q.S.; Ta, N. Exploring Value Capture Mechanisms for Heritage Protection under Public Leasehold Systems: A Case Study of West Lake Cultural Landscape. Cities 2019, 86, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, B.; Kiliç, S.E. Tourism-Led Rural Gentrification in Multi-Conservation Rural Settlements: Yazıköy/Datça Case. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liang, Y.J.; Fuller, A. Tracing Agricultural Land Transfer in China: Some Legal and Policy Issues. Land 2021, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.C.; Xu, Y.H.; Pang, X.C.; Yao, X.J.; Hao, M.J.; Jin, C.Y. Study on Land Incremental Value Distribution based on Contribution-Risk Analysis of Farmland Acquisition. China Land Sci. 2017, 31, 28–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L. Structural Equation Modeling: Operations and Applications of AMOS; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J.R. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bellato, L.; Pollock, A. Regenerative tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S | A | A, B | A, C | A, B, C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V(S) | 0 | V(A,B) | 0 | V(A,B,C) |

| V(S\{G}) | 0 | V(B) | 0 | V(B,C) |

| V(S) − V(S\{G}) | 0 | V(A,B) − V(B) | 0 | V(A,B,C) − V(B,C) |

| |S| | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| (n − |S|)!(|S| − 1)! | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| w(|S|) | 1/3 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/3 |

| Core Categories | Initial Categories | Concept Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs of production factors | Land resource input | Land, with its specific natural attributes and economic value, is utilized as a component of production factors to meet production or construction needs through development and use. |

| Infrastructure investment | This process enhances land development value by improving the completeness of public facilities and ancillary infrastructure in the area. | |

| Inputs of production factors | Labor input | The staffing of positions such as service, management, operation and maintenance strengthens the human resources system of the rural tourism industry. |

| Talent and technology investment | Introducing professional talent and advanced technologies drives the high-quality development of the tourism industry. | |

| Community governance investment | Enhancing systematic investment in rural communities across areas such as public security, environmental protection, regulated commercial operations, and public service delivery. | |

| Demand and supply factors | Increasing land demand | Population growth driven by tourism development leads to increased land demand. |

| limited land supply | Factors such as the scarcity of natural resources, policy constraints, and complexities in land development result in a limited supply of developable land. | |

| Land conversion | Land function transformation | The land’s use changes, but its fundamental nature remains, such as converting homesteads into homestays. |

| Change in land ownership | Legal entitlements such as land ownership and use rights are transacted through statutory procedures, resulting in their transfer, alteration, or reconfiguration among different entities. | |

| Change in land nature | Legal rights and interests such as land ownership and usufruct are transferred, changed, or reallocated among different entities through legal procedures. | |

| Policy drivers | Policy adjustment | The government has adjusted policies on regional planning and land transfer to promote tourism development. |

| Policy support | The government has introduced incentive policies, such as tax breaks and interest-free loans, to support the rural tourism industry. | |

| Policy restrictions | The government regulates, guides, and macro-manages social conduct and development directions in relevant fields through laws and policies. | |

| Risk factors | Social risk | The conversion of rural land for tourism-oriented development may lead to conflicts and fairness issues. |

| Economic risk | The rural tourism sector faces challenges such as market volatility, high investment risks, and unmet profit expectations. | |

| Environmental risk | Tourism-oriented rural land development may cause natural resource depletion and environmental pollution. | |

| Legal risk | Land development and tourism operations may involve collusion and regulatory violations. | |

| Land value increment distribution | Value increment distribution principle | Land value increment should be distributed reasonably based on principles that balance public and private interests while recognizing contributions and risk-sharing. |

| Entities involved in value increment distribution | The distribution of land value increment involves the government, villagers, village collectives, and investors. | |

| Value increment distribution ratio | Distribution shares are determined based on participants’ contributions and claims. |

| Dimension | Number | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs of production factors (IP) | IP1 | Villagers’ investment in assets and service quality improvement can drive land value increment. | Sun and Cao [5] interview text |

| IP2 | Government investment in infrastructure can enhance land prices. | Xie et al. [24] interview text | |

| IP3 | Multi-stakeholder resource investment and environmental improvements are significant factors contributing to rising land prices. | Li et al. [36] | |

| IP4 | Government initiatives in talent introduction and skill training to improve the business environment can attract tourists and investment, thereby increasing land value. | Yu et al. [37] | |

| IP5 | Government governance of community and commercial environments enhances regional attractiveness and drives up land prices. | Kumar et al. [38] | |

| Demand and supply factors (DS) | DS1 | Employment and income growth generated by the tourism service industry will increase land demand and prices. | Sun and Cao [5] interview text |

| DS2 | Rural tourism drives the development of related industries, thereby increasing land demand and prices. | Sun and Cao [5] interview text | |

| DS3 | The population agglomeration effect triggered by rural tourism, coupled with increasing land demand, promotes land price appreciation. | Sun and Cao [5] interview text | |

| DS4 | External investment attracted by tourism development increases land demand, leading to higher land prices. | Cunha et al. [39] | |

| DS5 | Transfer and consolidation of fragmented land parcels can improve land use efficiency and returns. | Gao and Cheng [40] | |

| Land conversion (LC) | LC1 | Assigning commercial functions to rural residential land can lead to increased land returns. | Wang et al. [41] interview text |

| LC2 | Change in land nature from collective to state-owned with transfer results in substantial land price increases. | Li et al. [42] | |

| LC3 | Expanding land uses and functions through transfer can generate higher land returns. | Tang [43] | |

| LC4 | Land function transformation from agricultural to tourism purposes promotes land price appreciation. | Tang [43] | |

| Policy drivers (PD) | PD1 | Policy adjustment in land policies influences land prices. | Ma et al. [6] |

| PD2 | Tourism industry support policies indirectly affect land prices. | Ma et al. [6] interview text | |

| PD3 | The introduction and adjustment of profit distribution policies impact interest allocation among different entities. | Wu et al. [44] | |

| Risk factors (RF) | RF1 | Unreasonable land resettlement compensation may widen rural income disparities and affect farmers’ livelihoods. | Ma et al. [6] |

| RF2 | The multitude of entities involved in profit distribution easily leads to interest conflicts and social issues due to unfair allocation. | Ma et al. [6] | |

| RF3 | Land tourismization transfer and development may cause environmental damage and loss of local cultural heritage. | Sözen and Kiliç [45] | |

| RF4 | Irregular construction and other improper practices may occur in tourism operations. | Sözen and Kiliç [45] | |

| Land value increment (LI) | LI1 | Land transfer or expropriation due to tourism development typically leads to price increases. | Sun and Cao [5] |

| LI2 | Market land demand and competition levels influence land value increment. | Sun and Cao [5] | |

| LI3 | Input of production factors and the extent of infrastructure development affect land prices. | Sun and Cao [5] | |

| LI4 | The adjustment and refinement of relevant policies contribute to achieving fair distribution of land value increment benefits. | Zhou et al. [46] | |

| Land value increment distribution (LD) | LD1 | Land value increment benefits distribution should balance the interests of the government, villagers, and developers. | Ma et al. [6] interview text |

| LD2 | Land value increment benefits distribution should balance stakeholder interests with public interests. | Ma et al. [6] | |

| LD3 | Land value increment benefits distribution needs to consider the contributions of various stakeholders. | Ma et al. [6] interview text | |

| LD4 | Land value increment benefits distribution should consider the risk-bearing of stakeholders. | Xu et al. [47] |

| Relational Architecture | Contextual Significance |

|---|---|

| Inputs of production factors → Land value increment | The input of production factors such as land resources, infrastructure development, and labor directly drives up land prices. |

| Demand and supply factors → Land value increment | Changes in land supply–demand dynamics directly influence land value appreciation. As tourism develops, rising demand for rural land creates market shortages, consequently pushing land prices upward. |

| Land conversion → Land value increment | Shifts in land function, ownership, or nature often lead to significant changes in land value. |

| Policy drivers → Land value increment | Land value appreciation is directly affected by policy-driven factors. Government decisions in regional planning and land transfer policies can substantially alter land prices. |

| Policy drivers → Land value increment distribution | The distribution of land value increment is directly influenced by policy interventions. Government-established land acquisition and compensation policies significantly shape allocation outcomes. |

| Land value increment → Land value increment distribution | Land value enhancement plays a decisive role in distributing the generated increment, establishing a causal relationship between the two. The source of value creation serves as key basis for allocation. |

| Risk factors → Land value increment distribution | Risk factors directly impact the distribution of land value increment, where stakeholders’ exposure to environmental, social, economic, and legal risks critically determines allocation outcomes. |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 329 | 49.47 |

| Female | 336 | 50.53 | |

| Age | ≤30 | 44 | 6.62 |

| 31–40 | 80 | 12.03 | |

| 41–50 | 175 | 26.32 | |

| 51–60 | 234 | 35.19 | |

| ≥61 | 132 | 19.85 | |

| Education level | Primary school or below | 220 | 33.08 |

| Junior high school | 298 | 44.81 | |

| High school/Vocational school | 81 | 12.18 | |

| Associate/Bachelor’s degree | 62 | 9.32 | |

| Master’s degree or above | 4 | 0.60 | |

| Stakeholder type | Villager operator | 249 | 37.44 |

| Other villager | 237 | 35.64 | |

| Local official | 74 | 11.13 | |

| Investor/Developer | 105 | 15.79 | |

| Annual income (CNY) | ≤10,000 | 108 | 16.24 |

| 10,000–50,000 | 201 | 30.23 | |

| 50,000–100,000 | 219 | 32.93 | |

| 100,000–150,000 | 87 | 13.08 | |

| ≥150,000 | 50 | 7.52 | |

| Total | 665 | 100.0 | |

| Item | Factor | Communality (h2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| IP1 | 0.746 | 0.160 | 0.076 | 0.128 | 0.031 | 0.083 | 0.072 | 0.617 |

| IP2 | 0.780 | 0.211 | 0.079 | 0.187 | 0.043 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.696 |

| IP3 | 0.794 | 0.180 | 0.090 | 0.206 | 0.020 | −0.006 | 0.082 | 0.721 |

| IP4 | 0.806 | 0.090 | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.019 | −0.022 | 0.050 | 0.667 |

| IP5 | 0.784 | 0.035 | 0.044 | −0.019 | −0.007 | −0.061 | 0.059 | 0.626 |

| DS1 | 0.159 | 0.745 | 0.056 | 0.094 | 0.024 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.593 |

| DS2 | 0.126 | 0.785 | 0.002 | 0.046 | 0.060 | −0.073 | 0.217 | 0.690 |

| DS3 | 0.065 | 0.768 | 0.041 | 0.019 | −0.004 | 0.118 | 0.124 | 0.625 |

| DS4 | 0.120 | 0.731 | −0.019 | 0.163 | 0.078 | 0.083 | 0.120 | 0.604 |

| DS5 | 0.175 | 0.787 | 0.175 | 0.096 | 0.051 | 0.079 | 0.030 | 0.699 |

| LC1 | 0.121 | 0.077 | 0.855 | 0.105 | 0.109 | 0.044 | 0.084 | 0.784 |

| LC2 | 0.015 | 0.027 | 0.873 | 0.082 | 0.084 | 0.084 | 0.113 | 0.797 |

| LC3 | 0.273 | 0.143 | 0.735 | 0.164 | 0.097 | 0.064 | 0.082 | 0.683 |

| LC4 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.862 | 0.006 | 0.118 | 0.072 | 0.119 | 0.776 |

| PD1 | 0.079 | 0.185 | 0.146 | 0.111 | 0.002 | 0.039 | 0.806 | 0.725 |

| PD2 | 0.117 | 0.138 | 0.067 | 0.041 | 0.077 | 0.016 | 0.896 | 0.847 |

| PD3 | 0.065 | 0.130 | 0.171 | 0.091 | 0.160 | 0.057 | 0.829 | 0.774 |

| RF1 | −0.102 | −0.001 | 0.055 | 0.028 | 0.232 | 0.785 | 0.072 | 0.690 |

| RF2 | 0.061 | 0.055 | 0.064 | −0.043 | −0.024 | 0.807 | −0.030 | 0.666 |

| RF3 | −0.018 | 0.028 | −0.007 | 0.056 | 0.043 | 0.777 | 0.050 | 0.612 |

| RF4 | 0.043 | 0.101 | 0.127 | 0.042 | 0.034 | 0.788 | 0.016 | 0.653 |

| LI1 | 0.091 | 0.135 | 0.087 | 0.789 | 0.110 | −0.045 | 0.113 | 0.683 |

| LI2 | 0.134 | 0.153 | 0.031 | 0.799 | 0.082 | 0.001 | 0.165 | 0.715 |

| LI3 | 0.115 | 0.052 | 0.041 | 0.812 | 0.047 | 0.076 | 0.028 | 0.685 |

| LI4 | 0.088 | 0.058 | 0.177 | 0.793 | 0.204 | 0.057 | −0.051 | 0.719 |

| LD1 | 0.083 | 0.095 | 0.015 | 0.105 | 0.763 | 0.020 | 0.129 | 0.626 |

| LD2 | −0.003 | 0.045 | 0.130 | 0.168 | 0.794 | 0.101 | 0.060 | 0.692 |

| LD3 | −0.065 | 0.060 | 0.200 | 0.127 | 0.771 | 0.110 | −0.061 | 0.674 |

| LD4 | 0.065 | −0.013 | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.807 | 0.037 | 0.090 | 0.669 |

| Fit Indices | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | RMR | IFI | TLI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance threshold | <3 | <0.08 | <0.05 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| Measurement model results | 2.103 | 0.057 | 0.030 | 0.921 | 0.908 | 0.921 |

| Initial model results | 2.104 | 0.057 | 0.032 | 0.920 | 0.908 | 0.919 |

| Modified model results | 2.103 | 0.057 | 0.032 | 0.920 | 0.908 | 0.919 |

| Estimate | S.E. | T | p | CR | AVE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP1 | ← | FP | 0.678 | 0.855 | 0.601 | |||

| FP2 | ← | FP | 0.873 | 0.088 | 13.758 | *** | ||

| FP3 | ← | FP | 0.887 | 0.089 | 13.856 | *** | ||

| FP4 | ← | FP | 0.628 | 0.083 | 10.431 | *** | ||

| DS1 | ← | DS | 0.690 | 0.848 | 0.528 | |||

| DS2 | ← | DS | 0.754 | 0.075 | 11.995 | *** | ||

| DS3 | ← | DS | 0.700 | 0.078 | 11.262 | *** | ||

| DS4 | ← | DS | 0.707 | 0.079 | 11.350 | *** | ||

| DS5 | ← | DS | 0.779 | 0.075 | 12.303 | *** | ||

| PT1 | ← | PT | 0.777 | 0.883 | 0.717 | |||

| PT2 | ← | PT | 0.865 | 0.095 | 16.509 | *** | ||

| PT3 | ← | PT | 0.894 | 0.084 | 16.772 | *** | ||

| PD1 | ← | PD | 0.749 | 0.862 | 0.677 | |||

| PD2 | ← | PD | 0.898 | 0.074 | 15.110 | *** | ||

| PD3 | ← | PD | 0.815 | 0.065 | 14.582 | *** | ||

| RF1 | ← | RF | 0.750 | 0.808 | 0.513 | |||

| RF2 | ← | RF | 0.709 | 0.084 | 11.302 | *** | ||

| RF3 | ← | RF | 0.685 | 0.080 | 10.994 | *** | ||

| RF4 | ← | RF | 0.718 | 0.086 | 11.414 | *** | ||

| LA1 | ← | LA | 0.786 | 0.855 | 0.601 | |||

| LA2 | ← | LA | 0.805 | 0.080 | 14.431 | *** | ||

| LA3 | ← | LA | 0.723 | 0.078 | 12.997 | *** | ||

| LA4 | ← | LA | 0.733 | 0.069 | 13.189 | *** | ||

| LD1 | ← | LD | 0.665 | 0.848 | 0.528 | |||

| LD2 | ← | LD | 0.785 | 0.090 | 11.275 | *** | ||

| LD3 | ← | LD | 0.729 | 0.114 | 10.783 | *** | ||

| LD4 | ← | LD | 0.709 | 0.086 | 10.577 | *** |

| LD | LI | RF | PD | LC | DS | IP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | 0.723 | ||||||

| LI | 0.328 | 0.763 | |||||

| RF | 0.244 | 0.098 | 0.716 | ||||

| PD | 0.222 | 0.247 | 0.112 | 0.823 | |||

| LC | 0.298 | 0.220 | 0.200 | 0.270 | 0.847 | ||

| DS | 0.167 | 0.326 | 0.151 | 0.362 | 0.172 | 0.727 | |

| IP | 0.115 | 0.375 | 0.025 | 0.246 | 0.171 | 0.426 | 0.775 |

| AVE | 0.523 | 0.582 | 0.513 | 0.677 | 0.717 | 0.528 | 0.601 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land value increment ← Inputs of production factors | 0.247 | 0.065 | 3.801 | *** |

| Land value increment ← Demand and supply factors | 0.126 | 0.056 | 2.243 | 0.025 |

| Land value increment ← Land conversion | 0.140 | 0.064 | 2.173 | 0.030 |

| Land value increment ← Land conversion | 0.084 | 0.063 | 1.339 | 0.181 |

| Land value increment distribution ← Policy drivers | 0.269 | 0.065 | 4.138 | *** |

| Land value increment distribution ← Land value increment | 0.152 | 0.048 | 3.184 | 0.001 |

| Land value increment distribution ← Risk factors | 0.125 | 0.059 | 2.116 | 0.034 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land value increment ← Inputs of production factors | 0.251 | 0.065 | 3.883 | *** |

| Land value increment ← Demand and supply factors | 0.147 | 0.054 | 2.740 | 0.006 |

| Land value increment ← Land conversion | 0.161 | 0.062 | 2.585 | 0.010 |

| Land value increment ← Land conversion | 0.274 | 0.065 | 4.244 | *** |

| Land value increment distribution ← Policy drivers | 0.151 | 0.048 | 3.173 | 0.002 |

| Land value increment distribution ← Land value increment | 0.128 | 0.058 | 2.205 | 0.027 |

| Land value increment distribution ← Risk factors | 0.251 | 0.065 | 3.883 | *** |

| Goal Level A | Criterion Level B | Indicator Level C |

|---|---|---|

| Rural land tourismization value increment distribution | Marginal contributions (B1) | Shapley value |

| Land value increment contribution (B2) | Land resource input | |

| Labor input | ||

| Direct capital input | ||

| Infrastructure development | ||

| Development of related industries | ||

| Increase in population density | ||

| change in land use | ||

| Policy drivers (B3) | Adjustment to regional planning | |

| Introduction of preferential policies | ||

| Adjustment to land transfer and use policies | ||

| Stipulation and adjustment of value increment distribution policies | ||

| Risk factors (B4) | Pressure on social security | |

| Intensification of interest conflicts | ||

| Rural environmental degradation | ||

| Risk of non-compliance |

| Matrix Dimension | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Zhao, T. Distribution of the Land Value Increment in the Context of Rural Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411024

Zhang P, Li J, Wang J, Li R, Zhao T. Distribution of the Land Value Increment in the Context of Rural Tourism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411024

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Puwei, Jiaming Li, Jia Wang, Rui Li, and Tengfei Zhao. 2025. "Distribution of the Land Value Increment in the Context of Rural Tourism" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411024

APA StyleZhang, P., Li, J., Wang, J., Li, R., & Zhao, T. (2025). Distribution of the Land Value Increment in the Context of Rural Tourism. Sustainability, 17(24), 11024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411024