1. Introduction

Human capital is a key driver of long-term productivity and sustainable growth. Globally, its measurement and monitoring have been institutionalized through the World Bank’s Human Capital Project and the SDG agenda, where Goals 4 (“Quality Education”) and 8 (“Decent Work and Economic Growth”) explicitly link investments in education and health to inclusive development. In the wake of the COVID-19 post-pandemic shifts, the risk of eroding accumulated human-capital gains remains high, heightening the demand for analytical tools that can identify territorial bottlenecks and support targeted capacity building [

1].

At the same time, measuring human capital at the subnational level entails methodological choices regarding the set of indicators, normalization, weighting, and aggregation. Composite indices are convenient for interregional comparisons, but they require transparent procedures and robustness checks to ensure that results are stable under alternative specifications [

2,

3,

4].

International studies based on large-scale subnational datasets provide compelling evidence that disparities in human capital are closely linked to regional differences in development and productivity. A seminal global study by Gennaioli et al. [

5] demonstrates that human capital disparities are one of the strongest predictors of regional income and productivity gaps. For China, Fraumeni et al. [

6] show substantial interprovincial inequalities in human capital stocks, which are directly linked to differences in long-term economic performance. Recent evidence from Indonesia’s Subnational Human Capital Index [

7] highlights pronounced spatial variation in human capital across provinces and districts, with consequences for future productivity and labor market outcomes. Spatial panel studies for China [

8] further indicate that upgrading the structure of human capital significantly improves the quality of economic development, revealing clear regional differentiation. Similar patterns are observed in low- and middle-income countries, where subnational disparities in education and human capital are strongly associated with life-expectancy differences and broader development inequalities [

9]. Together, these findings form a consistent body of evidence linking territorial human-capital disparities with uneven regional development trajectories. Local knowledge spillovers and the quality of the workforce account for a substantial share of interregional differentiation. However, Kazakhstan remains underrepresented in this literature at the regional level, particularly with respect to reproducible, methodologically consistent assessments over a long time horizon. As a result, a gap persists between national-level human capital indices and the practical demands of regional policy, where decisions are made at the level of oblasts and urban agglomerations [

5].

Central Asia as a macro-region exhibits structural challenges that make subnational human capital assessments particularly relevant. Despite overall improvements in education and health indicators, the region remains characterized by pronounced economic heterogeneity, persistent rural–urban divides, rapid demographic change, and significant environmental pressures linked to water scarcity, air pollution, and climate vulnerability. Countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan demonstrate similar internal disparities, where capitals and major urban agglomerations accumulate skilled labor, while remote regions experience depopulation, lower accessibility of social services, and labor market instability. These conditions underscore the importance of moving beyond national averages to regionalized assessments, which remain extremely limited in the Central Asian context. By placing Kazakhstan within this broader regional landscape, the study addresses a critical empirical gap in Central Asian scholarship on spatial inequality in human capital.

Over the past decades, Kazakhstan has achieved steady progress on aggregate human development indicators; however, gaps in the quality and accessibility of educational services—and across components of human capital—persist within the country. In several regions, including areas with intensive resource extraction, the most severe constraints involve shortages of preschool places, and problems with education quality remain, driven by rapid demographic growth and infrastructure deficits [

10]. At the same time, the national human capital index remains below the OECD average and is sensitive to whether and how the quality of higher education is taken into account. UNDP updates for 2023–2025 likewise confirm the country’s high overall level of human development alongside substantial inequalities that call for targeted policies. In this context, spatially detailed assessments and maps of human capital become an essential tool for prioritizing investments and advancing SDGs 4 and 8 [

11].

The focus on regional human capital is justified by the fact that economic growth, labor productivity, and demographic sustainability manifest unevenly across subnational territories. National aggregates mask territorial contrasts that directly influence regional competitiveness, labor market supply, and long-term development resilience. Human capital is accumulated, maintained, and utilized locally; therefore, regions differ not only in levels of education and health, but also in their ability to convert these resources into economic performance. Assessing human capital at the regional level is therefore essential for formulating targeted and SDG-aligned policies in a geographically diverse country such as Kazakhstan.

The aim of this article is to develop a composite human capital index for Kazakhstan’s regions and to analyze its spatial differentiation over 2000–2020. Based on a harmonized set of indicators covering education, health, and demographic–labor characteristics, we construct a composite index using transparent normalization procedures. The spatial analysis relies on cartographic visualization of the subindices and the composite measure, enabling clear identification of territorial clusters and disparities. This approach ensures temporal comparability of results and their practical applicability to regional cohesion and equalization policies [

12]. The research hypothesis is that human capital in Kazakhstan is unevenly distributed, with persistent spatial disparities shaped by demographic dynamics and access to social services, which in turn largely determine the prospects for achieving the SDG.

The contribution of this study is threefold. First, it proposes a unified methodology for measuring human capital at the regional level in Kazakhstan, enabling comparable assessments and composite indicators. Second, it conducts a cartographic analysis of the subindices and the composite index, paving the way for formulating targeted policy actions. Third, it demonstrates how subnational assessment results can be embedded in the SDG agenda and national strategies by prioritizing investments in education and health, as well as by monitoring regional trajectories with due regard for interregional linkages. Taken together, this provides a foundation for systemic, future-oriented human capital governance that minimizes the risks of spatial polarization and strengthens the potential for sustainable growth.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Human Capital in the Global Development Agenda

Human capital has traditionally been viewed as a key driver of long-term economic growth, social resilience, and inclusive development. In economics, the concept was formalized in the works of Schultz and Becker, who demonstrated that investments in education and health yield effects comparable to physical investments in productive capacity [

13,

14]. The further development of human capital ideas is associated with endogenous growth models, in which knowledge and skills serve as the primary drivers of productivity gains [

15,

16]. The central implication of these theories is that economic dynamics are determined not only by the accumulation of physical factors of production but also by the qualitative characteristics of the labor force.

At the global level, the institutionalization of human capital measurement has advanced through the World Bank’s Human Capital Project initiative [

17]. Within this initiative, the Human Capital Index (HCI) is calculated, integrating indicators of child survival, expected years of schooling and education quality, as well as the expected productivity of health. The project’s goal is to show countries how the level of human capital today determines the possibilities of their economies tomorrow. This initiative has become one of the most ambitious attempts to introduce into practice a comparable quantitative tool for monitoring “human assets” in international development policy.

A special place is occupied by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the United Nations in 2015. Among the 17 SDGs, SDG 4 and SDG 8 directly reflect the measurement and advancement of human capital. SDG 4, “Quality Education,” emphasizes ensuring universal access to education and improving its quality. SDG 8, “Decent Work and Economic Growth,” underscores the need to invest in skills, raise labor productivity, and expand employment.

Unlike earlier international development frameworks that focused primarily on macroeconomic indicators, the SDGs integrate social, demographic, and educational components into a single system of goals, thereby institutionalizing the role of human capital as a global priority.

At the same time, contemporary discourse highlights the risks of eroding accumulated gains. The COVID-19 pandemic posed a major challenge, with many countries experiencing setbacks in educational and health outcomes. Studies by the World Bank [

11], UNESCO [

18], and UNICEF [

19] document a loss of up to two years of learning in primary school in developing countries, a rise in the share of children who have not reached a minimum level of literacy by age 10 (“learning poverty”), and a decline in coverage of preventive health services. These developments have intensified the demand for new analytical tools capable of identifying territorial bottlenecks and supporting targeted interventions.

An important strand of the international discussion has been the development of methodologies for composite indices that integrate diverse indicators of education, health, and demographic structure. The OECD Handbook on Composite Indicators provides the conceptual foundations for indicator selection, normalization choices and weighting strategies, and emphasizes transparency and reproducibility as requirements for composite measures [

2]. The JRC methodological guidelines further formalize the technical steps of constructing robust indices, including dominance checks, correlation screening and consistency tests for normalization and aggregation procedures [

3]. In addition, the seminal contribution by Saisana, Saltelli and Tarantola introduced a systematic framework for sensitivity and uncertainty analysis, demonstrating how the stability of composite scores must be assessed under alternative specifications [

4]. Together, these sources define the international methodological standards that guided the design of the Regional Human Capital Index in this study.

Contemporary research confirms that disparities in human capital are closely linked to territorial differentiation in development. Using a large body of subnational data, Gennaioli, La Porta, López-de-Silanes, and Shleifer [

5] showed that differences in human capital account for a substantial share of interregional gaps in productivity and income levels. This conclusion has been corroborated by studies on Latin American countries [

20] and on China [

21]. Thus, human capital is viewed not only as a driver of macroeconomic growth but also as a key instrument for reducing regional inequality.

At the same time, the global literature notes the exceptionally limited representation of Central Asia—and Kazakhstan in particular—in comparable, reproducible studies. The presence of aggregated national indices (e.g., the HDI or the World Bank’s HCI) does not compensate for the absence of subnational assessments, which complicates the design of effective regional policy. This is the principal research gap underscored by UNDP [

22], the World Bank [

11], and regional analytical centers.

Accordingly, the global review confirms that human capital is entrenched in the international agenda as a key driver of sustainable development, requiring measurement through composite indices recognized by leading organizations and research centers. The spatial differentiation of human capital substantially explains regional disparities in productivity and growth rates, revealing clusters of advantage and zones of vulnerability. Against this backdrop, Kazakhstan and Central Asia remain under-studied, which justifies the present study, oriented toward developing index-based approach and GIS analytics to support targeted, long-term regional policy.

2.2. Approaches to Measuring Human Capital

Over recent decades, the measurement of human capital has evolved from aggregated national indicators to sophisticated composite indices that capture the phenomenon’s multidimensionality. Traditional approaches relied primarily on education metrics—literacy rates, school enrollment, or average years of schooling [

23]. Subsequent research, however, has demonstrated the limitations of such measures, as they fail to reflect education quality, population health, or socio-demographic characteristics that directly affect productivity and the sustainability of growth [

20].

The most widely used instrument has been the Human Development Index, developed by UNDP [

24]. It integrates indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income, enabling cross-country comparisons of human development levels. Despite its global recognition, the HDI has been criticized for the limited scope of its indicators and its low sensitivity to within-country disparities [

25].

Another important instrument is the World Bank’s HCI, introduced under the Human Capital Project [

17]. Unlike the HDI, the HCI focuses on the productivity of future workers, taking into account child mortality, expected years of schooling, education quality (based on international test scores), and health. The index is designed to capture the link between investments in human capital and future economic growth, which makes it a convenient policy tool; however, it remains an aggregate measure and does not account for regional disparities.

Methodological guidance in this field has been developed by the OECD and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). The classic Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators [

2] outlines the key steps in building indices, including sensitivity and robustness testing. Subsequent JRC publications—most notably Your 10-Step Pocket Guide to Composite Indicators & Scoreboards [

3]—place particular emphasis on the reproducibility of procedures and the transparency of methodological choices.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to subnational assessments of human capital, which make it possible to identify territorial disparities and design targeted policies. Examples include the European Regional Competitiveness Index [

26] where human capital is one of the key components, as well as regional indices in China [

21] and Latin America [

27]. These studies show that within-country differences in human capital often exceed cross-country disparities, making subnational assessments critically important for regional policy.

Thus, approaches to measuring human capital have evolved from simple education-based indicators to sophisticated composite indices that incorporate health and demographic characteristics. It is subnational assessments, however, that reveal spatial disparities and necessitate accounting for regional specificities—thereby directing the research toward an analysis of the spatial dimension of human capital.

In parallel with composite index methodologies, recent studies highlight the growing use of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) for evaluating the efficiency of human capital formation and related socio-economic processes. DEA provides an endogenous, non-parametric mechanism for deriving weights and benchmarking units based on the relative conversion of inputs into outputs. Notably, Ratner et al. [

28] applied a DEA-based framework to assess the efficiency of national innovation systems across post-Soviet countries, demonstrating the method’s suitability for human-capital-related inputs and outputs. Furthermore, Firsova [

29] employed a DEA–Malmquist model to evaluate the efficiency of regional sectors, confirming DEA’s capacity to capture multidimensional regional disparities. These studies illustrate that DEA represents a scientifically grounded complementary approach to composite indices, particularly in transition economies where territorial efficiency differences are pronounced.

2.3. Spatial Dimension of Human Capital

In recent decades, research on human capital has increasingly focused on its spatial differentiation. Regional disparities in educational attainment, access to healthcare, and demographic structure shape an uneven distribution of human capital, which directly influences the socio-economic dynamics of territories [

5]. The spatial approach makes it possible to identify not only average levels but also territorial clusters, areas of concentrated advantages or deficits, and interregional linkages that amplify—or, conversely, attenuate—the effects of policy.

International studies show that human capital exhibits pronounced spatial properties, including clustering and diffusion effects. In China [

21], regions with high levels of education and health form “growth belts” that attract investment and skilled labor. Similar results have been found for India and Latin America, where local knowledge spillovers strengthen the competitive positions of more developed regions and entrench the lag of less advantaged territories [

27].

Another structural determinant highlighted in recent empirical literature concerns the role of regional budget allocation mechanisms. Studies show that disparities in public expenditures on education, healthcare and social services reinforce spatial divergence in human capital outcomes, as regions with stronger fiscal capacity are able to sustain higher-quality human-capital investments over time. OECD identifies budget allocation asymmetry as a key driver of territorial inequality in human-capital formation across both developed and emerging economies [

30], while Libman and Vinokurov demonstrate that in post-Soviet countries fiscal centralization and concentration of resources in metropolitan areas systematically weaken peripheral regions’ ability to accumulate human capital [

31]. These findings indicate that regional fiscal architecture should be considered an integral factor shaping spatial differentiation in human capital.

An important complement to these findings is a growing body of research examining how effectively regions transform public expenditures into human-capital outcomes. DEA-based studies increasingly demonstrate that territorial differentiation is shaped not only by demographic and educational disparities but also by differences in budget utilization efficiency. For example, Firsova [

29] shows that regional sectors in transition economies exhibit substantial variation in input–output efficiency, which systematically influences human-capital dynamics.

Alongside statistics, cartographic methods are employed—including choropleth maps and typological classifications—which provide clarity and practical interpretability for regional policy. The spatial dimension of human capital is becoming a key element in shaping regional development strategies. In the European Union, the concept of “smart specialization” is directly linked to assessing regions’ educational and innovation potential [

32]. In OECD countries, the development of human capital is viewed as an instrument for reducing spatial inequality and stimulating “local growth” [

33]. Thus, human capital is no longer solely a macroeconomic category; it becomes a spatial indicator that is critically important for regional policy.

2.4. Central Asia and Kazakhstan: Current Evidence and Gaps

Research on human capital in Central Asia remains relatively limited compared to Europe, East Asia, or Latin America. Despite the efforts of international organizations—including the World Bank, UNDP, and UNICEF—the region is seldom examined within systematic comparative studies that emphasize the territorial differentiation of human capital. Most often, analysis focuses on the aggregate HDI, which records progress by Kazakhstan and neighboring countries on basic summary indicators but does not capture within-country disparities [

22]. Meanwhile, it is precisely the subnational level that is critically important, since regional imbalances in access to education and healthcare shape long-term differences in the renewal of the labor force and the sustainability of economic growth.

Central Asian countries exhibit similar trends: a high share of youth in the population structure, pronounced disparities between capitals and peripheral areas, and insufficient infrastructure in rural regions. According to the World Bank [

11], the quality of educational services in the region remains uneven, and preschool enrollment significantly lags behind OECD countries. UNDP [

22] notes that migration dynamics and regional imbalances exacerbate the risk of “losing” human capital, as working-age populations leave in search of higher incomes and depopulating areas lose their capacity for renewal.

Over recent decades, Kazakhstan has exhibited steady gains on aggregate human development indicators. By the HDI, the country falls into the high human development group, and according to the World Bank [

11] its Human Capital Index exceeds the regional average for Central Asian countries. However, a more granular examination reveals substantial regional disparities.

Studies by Nyussupova [

34,

35,

36] document that demographic processes—population aging, youth migration, and differences in fertility—shape territorial imbalances in labor resources. Aidarkhanova et al. [

10] show that rapid demographic growth in the southern and western regions is accompanied by a structural deficit of educational infrastructure, especially in preschool and primary education. These regions are simultaneously characterized by pronounced resource specialization, creating a “double gap”: high rates of child-population growth coupled with low provision of social services.

A study by Kiikova et al. [

37], conducted using the international ECERS-3 methodology, revealed low quality of preschool education in Kazakhstan, with differences observed irrespective of settlement type. This underscores the need not only to expand infrastructure but also to improve the quality of educational services.

Reports by the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies [

38] emphasize that the country’s “demographic window of opportunity” can be realized only if investments in human capital are made. Otherwise, rapid demographic growth will not translate into an economic dividend and will instead heighten social inequality. UNICEF and World Bank documents note that rural areas remain particularly vulnerable, characterized by low accessibility of healthcare services and a limited choice of educational institutions.

Moreover, Kazakhstan continues to face pronounced regional disparities in the quality of higher education. According to national studies, universities in major cities concentrate the best faculty and resources, while peripheral institutions do not provide a comparable level of training [

39,

40]. This leads to an outflow of applicants and graduates to the capital agglomerations, entrenching interregional inequality in human capital.

Despite accumulated data and individual empirical studies, systematic subnational assessments of human capital in Kazakhstan remain limited. First, most existing indices are constructed at the national level (HDI, HCI) and do not allow interregional differences to be identified. Second, even when regional analysis is conducted, it most often focuses on individual domains (education, healthcare, labor market) without integrating them into a single composite index. Third, there is a near absence of reproducible methodologies that could be applied for long-term monitoring and cross-regional comparison.

Recent advances in spatially oriented sustainability research further reinforce the need for subnational diagnostics. For example, Huang et al. [

41] demonstrate that regional disparities in development outcomes exhibit clear spatial clustering patterns, which supports our use of spatial dependence tests (Moran’s I) in this study.

Thus, a research gap persists despite the abundance of global and national indices, robust and comparable subnational assessments of human capital for Kazakhstan are lacking. Filling this gap has both scholarly and applied significance. Scholarly—because it enables Kazakhstan to be incorporated into the international literature on the spatial dimension of human capital. Applied—because it provides tools for targeted regional policy, investment prioritization, and the achievement of sustainable development goals at the level of oblasts and agglomerations.

Despite these advances, the empirical literature has not yet produced a coherent, reproducible subnational assessment of human capital for Kazakhstan that integrates demographic, social, economic and environmental dimensions into a unified analytical framework. Existing studies either rely on aggregated national indicators or examine individual components in isolation, which limits their diagnostic capacity. Accordingly, the present study addresses the following research gap: the absence of a multidimensional, methodologically transparent, and spatially explicit regional index of human capital for Kazakhstan.

Building on this gap, the study formulates the following working hypothesis: regions with stronger social and economic foundations—measured through education quality, healthcare capacity, labor market engagement and income structure—systematically outperform others on the composite human capital index, regardless of demographic size or geographic location. This hypothesis is tested empirically through a four-pillar composite framework and cross-regional comparisons over 2000–2020.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Framework and Object of the Study

This study adopts a composite approach to measuring human capital development at the regional level, ensuring territorial comparability, transparency of normalization and aggregation procedures, and reproducibility of results under the constraints of official statistics. Conceptually, it distinguishes between “human capital” and “human potential”: the former reflects realized knowledge, skills, and health that generate economic and social returns for individuals and society, whereas the latter denotes the stock of available resources that are not necessarily materialized in outcomes.

While “cost-based” and “income-based” valuations used in the classic literature and several international practices are important, their direct application at Kazakhstan’s subnational level faces challenges related to data completeness and comparability, as well as the treatment of non-monetary effects. Under these conditions, a composite index scheme is operationally preferable: it enables the measurement of a multidimensional construct through a harmonized set of statistical indicators, unified normalization rules, and transparent aggregation of subindices.

The territorial units of analysis are the regions of the Republic of Kazakhstan (oblasts and cities of republican significance), consistent with the availability and reliability of official statistics.

Although the empirical implementation relies on regional data from Kazakhstan, the structure of the Regional Human Capital Index (RHCI) was developed to be broadly applicable across different national contexts. The majority of indicators follow internationally recognized demographic, social, economic and environmental metrics, while only a limited subset reflects the specifics of Kazakhstan’s statistical system. In this sense, the empirical analysis demonstrates the operational feasibility of the framework in a real-world setting without limiting its applicability to other countries.

3.2. Data Sources and Indicators

The information base comprises the Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan [

42] and the Taldau portal [

43]; administrative data from line ministries—education, health, and labor [

44,

45,

46], the RSE “Kazhydromet” (Kazakhstan, Astana) [

47]; and, selectively, comparable indicators from international organizations [

48,

49].

Operationalization of human capital is implemented through a four-pillar indicator system that captures the key dimensions: the demographic foundation (reproduction, migration, population aging, and longevity); the social dimension (health and education, including the quality of educational attainment); the economic dimension (incomes, labor market participation, skill structure, and innovation activity as domains where capital is realized); and the environmental dimension (living-environment conditions as moderators of health and quality of life) (

Figure 1).

The principles for selecting indicators follow directly from the measurement objective: substantive relevance to the phenomenon of human capital; reliance on standard, officially published statistics; a preference for relative metrics to reduce scale and structural biases; and parsimony of the list while covering essential aspects. For several indicators, qualitative adjustments are applied to enhance validity: for example, the education component considers not only enrollment coverage but also learning outcomes (Unified National Testing, External Assessment of Learning Outcomes), which brings the measure closer to “effective years of schooling.”

Time series for all indicators are compiled as a continuous 2000–2020 panel without interpolation or extrapolation. The indicator set was chosen to ensure consistent dynamics of the subindices and the composite index over the entire observation period. The only exceptions are indicators from national knowledge-assessment systems: Unified National Testing (UNT), introduced in 2004, and the External Assessment of Learning Outcomes, introduced in 2012. Accordingly, UNT data are used for 2004–2019, and External Assessment data for 2012–2019; these indicators are neither extrapolated nor interpolated beyond their respective intervals. Aggregation of the social subindex (Equation (2)) takes into account the actual availability of UNT/External Assessment data, while the remaining indicators in this component ensure continuity of the overall dynamics for 2000–2020.

Extending the panel beyond 2020 would currently require combining fully observed pre-pandemic series with provisional and methodologically non-harmonized post-2020 data for several indicators, including income, morbidity, and educational quality measures. In addition, from 2022 onward the creation of new regions (Abai, Ulytau, Jetisu) complicates backward harmonization of regional statistics. To preserve temporal comparability and avoid structural breaks associated with COVID-19 shocks and administrative reorganization, the present study deliberately restricts the analysis to 2000–2020, while the extension of the index to the post-2020 period is left for follow-up research once a consistent time series becomes available.

Although the environmental pillar could in principle include a broader set of indicators (e.g., water quality, green space accessibility or soil degradation), the selection was constrained by data availability and temporal consistency across regions. For Kazakhstan, the Air Pollution Index and emissions-based metrics are the only environmental indicators that are systematically reported for all regions over the full study period. Moreover, many potentially relevant indicators are either unavailable at the regional scale, collected irregularly, or not harmonized across urban and rural areas. For these reasons, the environmental component is based on air quality–related proxies, which are the most consistent and comparable measures of environmental pressure affecting human capital in the Kazakhstani context.

All series are aligned to the administrative boundaries at the end of the period—17 regional units (14 oblasts plus the cities of Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent). Given that Shymkent was established as a separate administrative unit in 2018, its indicators are included within Turkistan region prior to 2018 and reported separately for the city of Shymkent from 2018 onward. Harmonization is based on officially recalculated data from the Bureau of National Statistics, ensuring comparability across time and space.

3.3. Normalization and Construction of Subindices

Normalization of individual indicators is performed using linear scaling, which ensures interpretability and reproducibility of results in interregional comparisons. Alternative techniques (rank-based and score-based normalization) are not employed here due to the loss of metric information in ranks and the heightened subjectivity inherent in choosing benchmarks for scores.

The selection of reference points combines fixed norms from international practice with empirical ranges from national data. For life expectancy at birth, lower and upper references of 25 and 85 years are used, consistent with the established Human Development Index methodology. For proportion indicators, the lower and upper bounds are naturally set at 0% and 100%, except for the gross enrollment rate in higher education (ages 18–22), which exceeds 100% in major centers due to interregional educational migration; in this case, the upper bound is taken as the actual regional maximum. Indicators lacking universal norms (e.g., natural increase, net migration, number of R&D personnel, per capita emissions, environmental protection expenditures, Air Pollution Index (API)) are normalized within the observed national range of values (

Table 1). For “reverse” indicators (e.g., infant mortality, morbidity/incidence, API, the share of persons aged 60+/65+ when interpreting aging as a risk), the scale is inverted.

The methodological choices applied in this study require explicit justification to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Linear min–max normalization was selected because it preserves the metric properties of the indicators and is widely recommended in the OECD–JRC Handbook on Composite Indicators for multidimensional regional comparisons. The 0–1 scaling facilitates the aggregation of heterogeneous indicators into harmonized subindices without distorting the relative contribution of each dimension. GIS-based mapping is used to capture spatial heterogeneity that cannot be adequately represented in numerical tables, while the five-level typology is derived using Sturges’ rule to ensure reproducible and statistically grounded classification thresholds. Finally, correlation analysis (Pearson and Spearman) is employed to assess internal consistency between subindices and the composite index and to identify the structural relationships among the components of human capital.

In addition, to validate whether regional variations in human capital exhibit a non-random spatial structure, we additionally computed the global Moran’s I statistic. This test is a standard methodological instrument in spatial econometrics and allows the detection of positive or negative spatial autocorrelation in the distribution of the composite index. Identifying significant spatial dependence is essential because it confirms that neighboring regions share similar trajectories, thereby justifying the use of spatially explicit diagnostics and providing a methodological foundation for future extensions of the model using spatial regression frameworks (e.g., SAR, SEM, SLX).

Subindices are computed as the arithmetic means of normalized indicators within each pillar, with an explicit adjustment for the education component. Specifically, when constructing indicators for secondary and higher education with a quality correction, we follow—by analogy—the HDI education index formula, where the learning-outcome index receives a weight of 2/3 and the enrollment index a weight of 1/3.

Accordingly, the subindices are defined as follows:

where

Dn,

Sn,

En, and

Eenv are the normalized indicators selected for the respective pillars. This construction preserves the internal logic of educational effectiveness (capturing not only access but also quality) and, in the economic block, balances the labor market dimension by jointly considering participation (labor force), employment, and qualification (the share of the employed with higher or incomplete higher education) while also accounting for firms’ innovation activity.

3.4. Composite Aggregation and Typology

The weighting scheme for composite aggregation reflects both the theoretical structure of human capital and the applied diagnostic objective. Greater weight is assigned to the social and economic pillars, where human capital is formed and realized; the demographic pillar captures the base of human-capital bearers and fundamental reproduction parameters; the environmental pillar acts as an important moderator of health and well-being, although, at the regional level, its operationalization partly relies on proxy indicators. The final Regional Human Capital Index is computed as a weighted sum of subindices:

where ∑

dem is the Demographic Subindex,

∑soc is the Social Subindex,

∑econom is the Economic Subindex,

∑env is the Environmental Subindex.

To ensure methodological transparency and address the reviewer’s concern regarding the weighting scheme, an explicit rationale and a full robustness check were incorporated. The chosen weights (0.20; 0.32; 0.32; 0.16) reflect the theoretical structure of human capital formation, where the social and economic pillars capture domains in which human capital is directly accumulated and realized, whereas the demographic pillar represents foundational conditions and the environmental pillar functions as a contextual moderator. This structure is aligned with established composite-indicator practice in the OECD–JRC framework, where dimension-specific conceptual roles justify asymmetric weights.

To verify that the weighting scheme does not drive the results, we conducted a multi-scenario sensitivity analysis.

Table S7 (Supplementary Material) reports regional RHCI values under three alternative weighting schemes: (i) equal weights; (ii) demographic–social emphasis; (iii) economic–environmental emphasis. Across all scenarios, regional ranks remain highly stable: no region shifts more than ±1 position. Deviations in RHCI values remain within a narrow corridor (0.008–0.021). This confirms that the composite index is structurally robust and not dominated by any single pillar. These results fully satisfy the OECD–JRC robustness criteria and validate the conceptual weighting structure adopted in Equation (5).

Each subindex is scaled to the [0, 1] range, and the composite (integral) index preserves the same metric.

Aggregation rules assume averaging at each level with the specified weights; geometric means are not used so as not to amplify the influence of zero or near-zero values and to keep interpretation straightforward. The final index range [0, 1] allows a direct reading: an increase in the value reflects an improvement in the state of human capital in the region relative to the adopted reference frame.

For analytical interpretation, typologization follows Sturges’ rule:

where

N is the number of regions. For

N = 17, we obtain

k = 5. Thresholds for the subindices and the composite index are set as equal-width intervals over the empirical range (

Table 2). These cut-off values are fixed and applied consistently in the typology and on the GIS maps.

The spatial implementation of the calculations is carried out using ArcGIS 10.8. A harmonized geocode base and a single map projection are used for all visualizations; choropleth maps of the composite index and subindices are produced with a unified legend and a fixed, direction-consistent color palette (improvement corresponds to higher values). The maps serve an analytic–illustrative function, supporting the interpretation of interregional differences and ensuring consistency with tabular results.

In addition to the methodological choices described above, further clarification is required to ensure full transparency and reproducibility of the graphical materials used in this study. The construction of maps and visual representations directly affects the interpretation of regional differences; therefore, the principles governing classification thresholds, color gradients, normalization ranges, and boundary harmonization must be explicitly stated.

To enhance the transparency and reproducibility of all graphical outputs, additional clarification regarding the construction of the figures is provided. The five-level classification applied in all maps is based on equal-width intervals derived from the empirical distribution of normalized subindex values. This approach ensures consistency and comparability across different pillars of the RHCI and across all years. Color gradients follow a sequential scheme recommended in statistical cartography, where lighter tones represent lower values of the indicator and darker tones correspond to higher levels.

All figures use a harmonized normalization range from 0 to 1, reflecting the min–max rescaling applied uniformly to the entire 2000–2020 period. This prevents shifts in classification thresholds between years and allows the analysis to focus on the spatial structure of disparities rather than scale changes. Administrative boundaries are unified to the post-2018 territorial division to avoid structural breaks, and all maps are produced using identical coordinate settings to guarantee visual comparability. Legends explicitly display interval thresholds, color scales, and units, enabling direct comparison across subindices and composite values.

Data quality is ensured through sequential control procedures: standardization of metadata and units of measurement prior to normalization; verification of extreme values for statistical and reporting anomalies; a strict completeness rule (the index is calculated only when values are available for all indicators within a block, or when an explicitly declared and methodologically justified imputation procedure is applied); and checks of inter-year comparability. Missing values that cannot be reliably reconstructed lead to exclusion of the corresponding observations from the subindex calculation, which is explicitly flagged in the analytical tables.

Taken together, the proposed methodology ensures substantive validity (a four-dimensional construct that accounts for the formation, realization, and context of human capital), statistical soundness (linear normalization, explicit references, transparent aggregation), and practical applicability (typology for policy reading and GIS visualization), making it suitable for regular monitoring and interregional comparison in Kazakhstan.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of the composite index, a sensitivity analysis was conducted following OECD–JRC recommendations for composite indicators. Three dimensions were tested:

Weight variation: alternative weighting schemes (equal weights; demographic–social emphasis; economic-environmental emphasis) were applied. Changes in regional ranking did not exceed 1–2 positions, indicating stability of results.

Normalization alternatives: z-score standardization and ranking-based normalization were compared to min–max scaling. The correlation between baseline and alternative composite indices remained high (Pearson R = 0.89–0.94), confirming robustness.

Indicator exclusion tests: sequential elimination of individual indicators showed that no single indicator drives the composite value; exclusion effects ranged from 1.5% to 4.3%. These tests demonstrate that the index is robust to methodological choices, and regional typology remains consistent across specifications.

4. Results

4.1. Dynamics of the Regional Human Capital Index

Over the twenty-year period from 2000 to 2020, Kazakhstan exhibits a positive trajectory in the composite Regional Human Capital Index, reflecting nationwide efforts to modernize the economy, improve social infrastructure, and raise living standards (

Figure 2).

The most pronounced gains are observed in the economic subindex, driven by investment in the extractive sector and growth in regional GRP. For example, in Atyrau region the economic subindex rose from 0.51 (2000) to 0.76 (2020), whereas in Kyzylorda region it increased from 0.45 to 0.58 (

Table S1). These differences underscore the uneven spatial pattern of economic growth (

Figure 3).

The social subindex also shows steady improvement, especially in the metropolitan areas and administrative centers, where physician and teacher availability and educational coverage have increased. The pace of growth, however, varies in Almaty and Astana the index rose by more than 20% (

Table S2), whereas in a number of peripheral regions it increased by less than 10% (

Figure 4).

The demographic subindex remains the most sensitive to regional disparities. For example, in Turkistan region over 2000–2020 there was a sustained predominance of high birth rates and net migration inflows, yielding stable subindex values (from 0.65 to 0.71) (

Table S3), whereas in the northern and eastern regions (North Kazakhstan and East Kazakhstan) declines were recorded, driven by population outflow and demographic aging (

Figure 5).

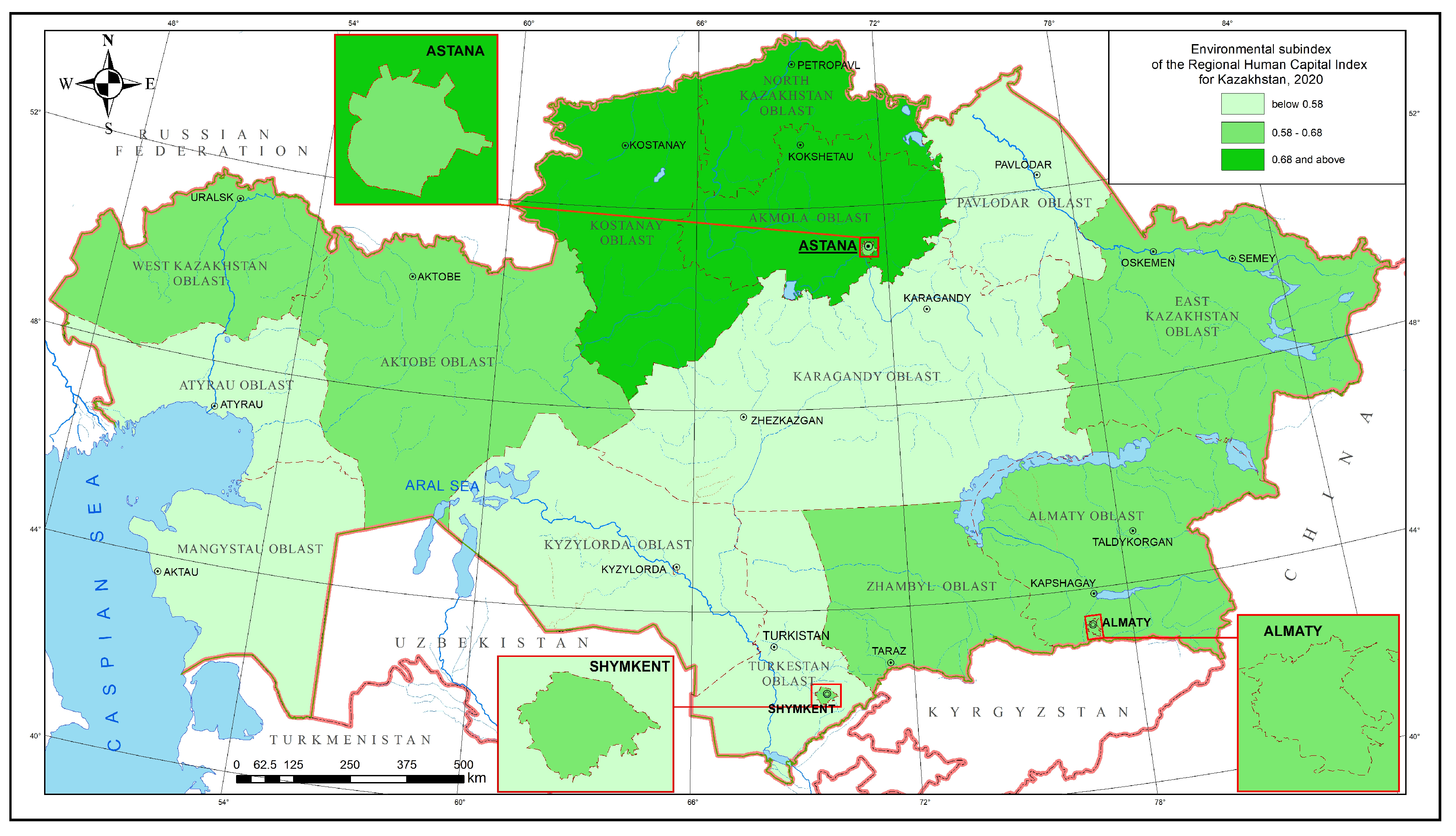

The environmental subindex presents a more complex picture. In some regions (Kostanay, North Kazakhstan) it remains relatively stable, whereas in heavily industrialized regions (Pavlodar, Karaganda) the environmental subindex declined, tempering gains in the composite index (

Table S4). In Pavlodar region, for instance, the environmental subindex fell from 0.66 in 2000 to 0.59 in 2020 (

Figure 6).

4.2. Spatial Typology of Regions by Human Capital Levels

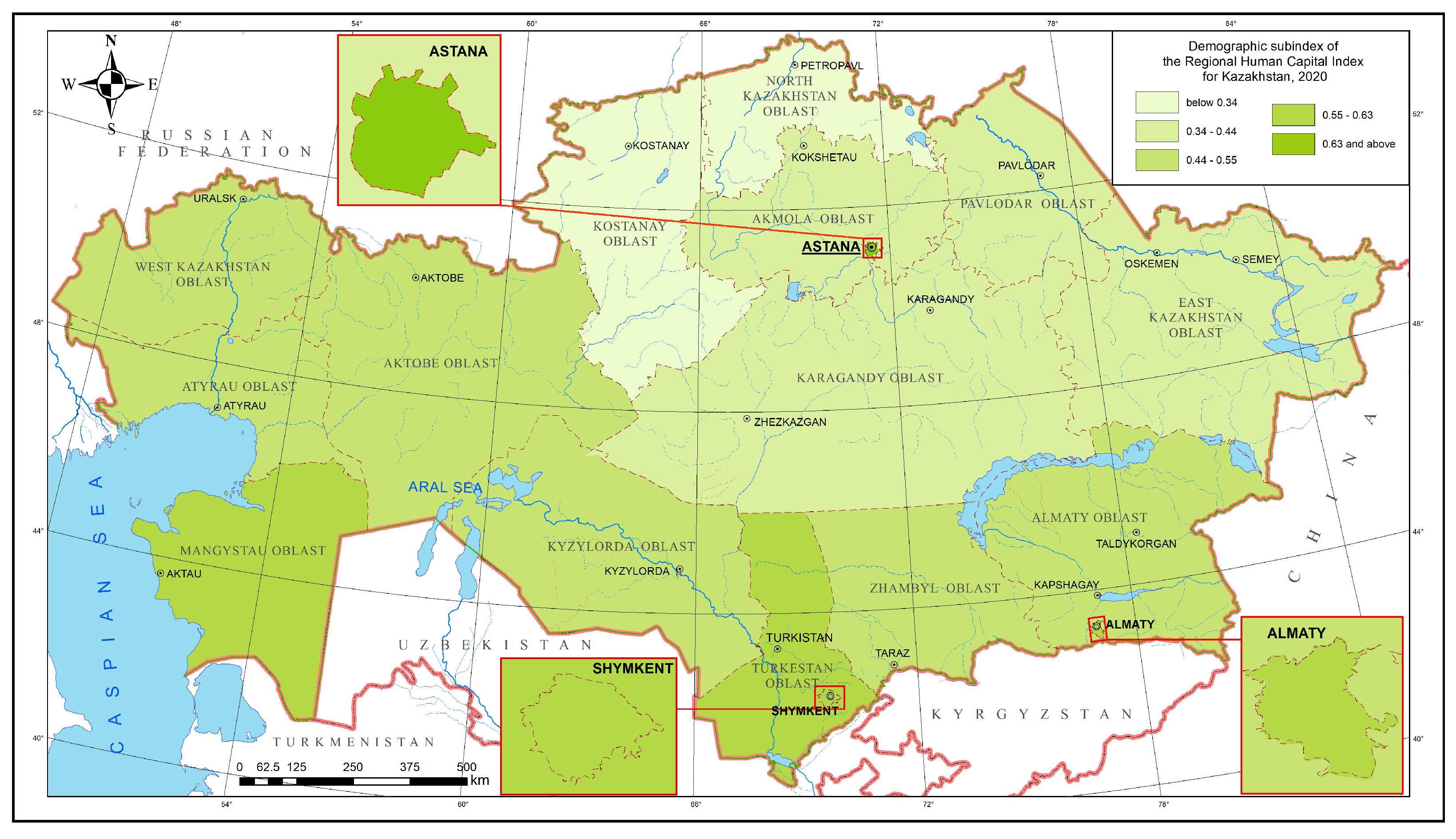

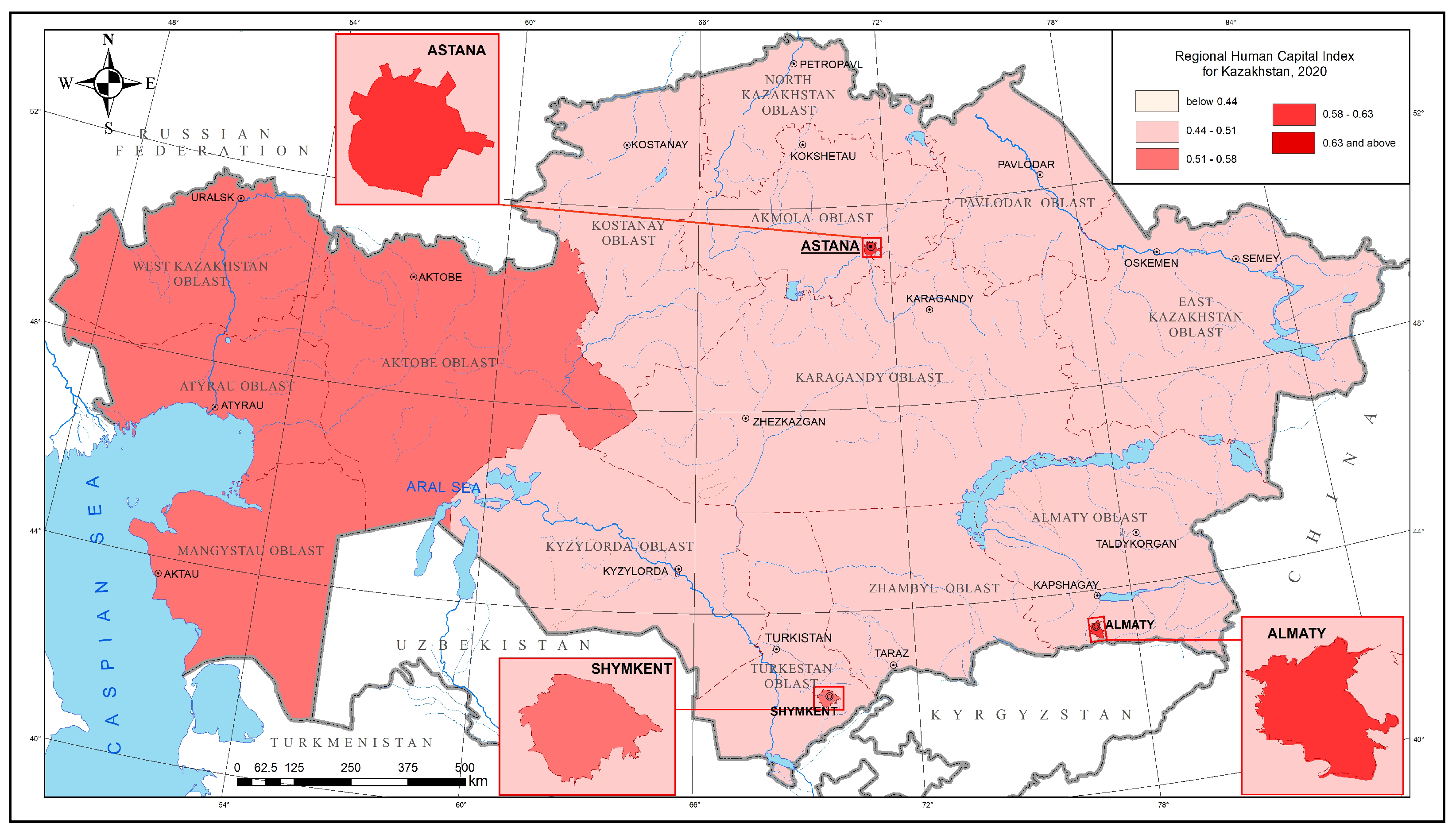

Spatial analysis of human capital development levels enabled a typology of all 17 regions of Kazakhstan, including the three cities of republican significance, based on the composite index for 2020. For analytical purposes, a five-level scale was delineated to capture interregional differences and stratification by the degree of comprehensive human capital development (

Figure 7).

A high level (≥0.720) is observed in three regions: the cities of Astana and Almaty, and Atyrau region. These regions exhibit sustained leadership across the index’s principal components—strong economic performance, well-developed health and education systems, positive demographic shifts, and a relatively favorable environmental situation. In Atyrau, economic dominance is particularly pronounced due to oil-and-gas specialization, whereas the two metropolitan cities constitute the core of the country’s intellectual and innovation potential.

An above-average level (0.680–0.719) is recorded in East Kazakhstan, Mangystau, Akmola, and Almaty regions. These territories are characterized by a relatively balanced structure of subindices and steady progress across most components. In Mangystau, economic potential is coupled with demographic growth, while in East Kazakhstan the social index has stabilized against a backdrop of moderate economic expansion.

An average level (0.640–0.679) typifies a set of industrial and agro-industrial regions—Zhambyl, Karaganda, Pavlodar, Turkistan—and the city of Shymkent (

Figure 7).

Despite relatively high fertility and demographic resources in the southern regions, challenges persist in social provision and environmental parameters. Industrial regions, in turn, post high GRP but face urbanization pressures and environmental burdens.

A below-average level (0.600–0.639) is reached by North Kazakhstan, Kostanay regions. These territories share demographic risks—natural population decline, a predominance of older age groups, and out-migration. Despite developed industrial infrastructure and production potential, low social and demographic subindices constrain the foundation for sustainable development.

A low level (<0.600) is found in Kyzylorda region—the most vulnerable profile in aggregate (

Table S5). Here, multiple weaknesses coincide: low coverage by education and health services, high pressure on the social support system, environmental degradation, and unstable economic dynamics. This configuration warrants priority policy support.

The resulting typology reveals pronounced territorial stratification: leading regions are concentrated in the west and south of the country, whereas lagging regions are located mainly in the central–northern belt. This underscores the uneven formation of human capital and points to the need for targeted territorial interventions aimed at reducing imbalances and strengthening the resilience of regions with vulnerable profiles.

To verify whether the spatial structure of human capital exhibits clustering patterns, we computed Global Moran’s I using a Queen contiguity matrix. The results confirm a statistically significant positive spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I = 0.312, p = 0.014), meaning that regions with similar RHCI values tend to be geographically grouped. Local indicators of spatial association (LISA) identify statistically significant clusters in the regional distribution of RHCI. The analysis reveals two high–high associations (Astana–Akmola and Almaty city–Almaty region) and a persistent low–low association in the northern belt (North Kazakhstan–Kostanay). These patterns indicate that regional human capital levels exhibit non-random spatial structure, which is consistent with the presence of localized spillovers and supports the application of spatial diagnostics in the present study.

As an additional validation step, we performed an unsupervised k-means clustering (k = 5) using the 2020 RHCI values. The resulting partition was highly consistent with the typology produced using Sturges’ rule: 14 out of 17 regions fell into the same class, and the remaining three differed by only one adjacent class. No region shifted across more than one category, confirming that the empirical distribution of RHCI values is naturally stratified into five clusters. This supports the statistical validity of the five-level typology adopted in this study.

Moreover, a high composite score does not always coincide with balanced subindices. Some regions display pronounced mismatches between strong economic potential and weaker environmental or demographic conditions. This calls for comprehensive adjustments to regional development strategies, emphasizing the balanced strengthening of all components of human capital.

4.3. Correlation Analysis of the Subindices and the Composite Index

Correlation analysis for 2019 indicates that variation in the composite index is driven primarily by the economic component: the Pearson correlation between the economic subindex and the composite index is R = 0.84, which denotes a very strong positive association. The contributions of the social (R = 0.87) and demographic (R = 0.74) subindices are statistically significant and substantial but comparatively lower; this suggests that, in interregional comparisons, economic differences most often determine a region’s position in the overall ranking. The environmental subindex warrants separate discussion, as it shows a weak negative correlation with the composite index (R = −0.24) (

Table 3). To verify robustness, Spearman rank correlations were also computed (

Table S6), which preserve the original ordering of associations.

This result is interpreted as the “cost” of industrial growth: regions with high economic activity and dense urbanization typically bear a greater environmental burden. Consequently, if the current structure of factors persists, efforts to raise human capital via economic drivers may entail environmental trade-offs unless offsetting mechanisms are built in (ecological modernization of production, green infrastructure, environmental quality standards).

Subindex profiles at the “points of influence” (major agglomerations and resource-rich regions) illustrate different architectures of association. In oil-and-gas regions, high economic scores coexist with moderate social metrics and vulnerable environmental parameters; in the capital agglomerations, strong economic and social positions are partially offset by the environmental constraints of the urban milieu. Conversely, some northern and eastern regions with more favorable environmental conditions exhibit average or below-average composite scores owing to demographic and economic constraints.

Thus, the economic subindex consistently shows the closest association with the composite index; the social and demographic subindices rank next; the environmental subindex is weakly negative. This does not imply causality, but rather the structure of joint variation across regions, and it reinforces the need for balanced policies: economic expansion without simultaneous improvements in social infrastructure, demographic resilience, and environmental conditions constrains long-run gains in the overall level of human capital.

The estimates confirm steady growth of the composite human capital index over 2000–2020 against the backdrop of pronounced interregional heterogeneity. The five-level typology records the sustained leadership of the two capital agglomerations and Atyrau region, while parts of the central–northern and southern regions remain vulnerable due to combinations of demographic, social, and/or environmental constraints. The correlation structure highlights the dominant role of the economic subindex in shaping the composite level, with the social and demographic components providing the “long trajectory” of human-capital accumulation, and the environmental component often acting as a brake in industry-intensive territories. The agglomeration effect consistently manifests itself in higher composite scores for large cities, but it is accompanied by elevated infrastructure and environmental pressures. For “demographic-growth” regions (the south), the key challenge is converting quantitative population gains into higher quality of education and employment; for the “industrial belt,” it is the modernization of environmental practices and the retention of the working-age population; for the “aging north,” compensatory migration and family-policy measures are paramount. Taken together, the results point to the need for differentiated regional policy aimed at alleviating the “bottlenecks” revealed by the subindices and balancing economic, social, demographic, and environmental priorities.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

The estimates confirm that growth in the composite Regional Human Capital Index over 2000–2020 is structural in nature and rests primarily on the economic component. The strong association between the composite measure and the economic subindex (R = 0.84) reflects the role of incomes, employment, and productivity as a rapid driver of interregional differentiation. At the same time, the social and demographic subindices shape the “long trajectory” of human-capital accumulation: they account for the long-run resilience of leaders and the vulnerability of lagging regions. The negative association with the environmental subindex points to a systemic risk: intensive industrial growth and population concentration without “green” modernization translate into environmental quality costs that, over the long term, constrain human-capital potential.

Beyond the empirical findings for Kazakhstan, the proposed methodological framework demonstrates broader applicability. Its four-pillar structure and normalization logic follow internationally recognized principles, enabling adaptation to other territorial systems where comparable regional statistics are available. This ensures that the empirical results presented here illustrate not only the spatial configuration of human capital in Kazakhstan but also the analytical potential of the framework in diverse national contexts.

The study has several limitations. First, the index depends on the completeness and reliability of official statistics, which vary across regions and years. Second, quality-oriented indicators of human capital (learning outcomes, health quality) remain only partially available and are represented through proxies. Third, administrative boundary harmonization may introduce structural breaks for Shymkent and Turkistan prior to 2018. Fourth, the analysis does not incorporate spatial econometric techniques, potentially underestimating spillover effects. Fifth, the temporal coverage is intentionally limited to 2000–2020, which is the last year for which a fully harmonized set of regional indicators is available prior to the combined effects of the COVID-19 shock and the 2022 administrative reorganization of regions. Incorporating 2021–2024 data would require mixing provisional and methodologically revised series, and is therefore reserved for a separate update of the index once stable, comparable statistics become available. These limitations do not undermine the core findings but suggest directions for further refinement.

A further limitation relates to the partial dependence of several indicators on the national statistical system. While the majority of components rely on internationally comparable demographic, social, economic and environmental metrics, certain education-related and environmental indicators reflect Kazakhstan’s reporting practices. When applying the framework in other contexts, such variables can be replaced with functionally equivalent measures. This ensures that the broader methodological architecture remains transferable while allowing for adaptation to country-specific data environments.

In addition to demographic and social dynamics, fiscal factors may also contribute to persistent spatial disparities. Regions with structurally lower budgetary capacity face constraints in sustaining investments in education, healthcare and social infrastructure, which may limit their long-term human-capital accumulation despite comparable demographic conditions.

Another methodological direction that merits further development is the use of efficiency-based approaches such as DEA. DEA allows regions to be evaluated according to how effectively they convert educational, demographic and health inputs into human-capital outputs, deriving weights endogenously rather than relying on fixed normative weights.

An additional methodological limitation concerns potential endogeneity between human capital and economic performance. The strong correlation observed (R = 0.84) may reflect bidirectional effects, whereby human capital both contributes to and depends on regional economic growth. Future studies should consider panel data models with instrumental variables or dynamic specifications to disentangle causal pathways.

The five-level typology records the sustained leadership of the two capital agglomerations and Atyrau region, a “zone of steady development” across parts of the eastern and Caspian regions, and vulnerable positions in the central–northern belt and Kyzylorda region. An important nuance is that a high composite level does not imply uniformity across subindices. In resource-producing regions, economic expansion is typically accompanied by weakening environmental sustainability: growth in extractive industries heightens anthropogenic pressures and risks of natural-system degradation. Southern regions follow a different path—intense demographic dynamics with high natural increase and net in-migration—yet social provision and infrastructure expansion lag behind population growth. In the country’s industrial belt, moderate economic growth is largely held back by demographic and environmental constraints: population aging, out-migration, and environmental pollution. This typology reflects divergent development paths, where a region’s sustainability is determined not only by the level of economic activity but by the balance among social, demographic, and environmental components. These configurations explain why similar composite levels can be reached via different trajectories and why identical policy measures yield heterogeneous effects.

Although the methodological framework was calibrated to Kazakhstan, the Regional Human Capital Index can be adapted to other Central Asian countries with minimal structural adjustment. The four-pillar system is fully transferable, while cross-country extension would primarily require harmonization of indicator definitions, alignment of administrative boundaries, and the unification of normalization ranges to ensure comparability. Given shared regional challenges—high demographic pressure, uneven accessibility of social services, and significant environmental stressors—the methodological template offers a scalable and conceptually coherent basis for cross-country diagnostics of human capital in Central Asia.

5.2. Alignment with International Approaches

The identified structure is consistent with international evidence: the contribution of economic factors to interregional variation in human capital is greater in the short run, whereas social and demographic determinants operate more slowly but more durably. Agglomeration externalities—concentrations of skilled labor, innovation, and complex services—push metropolitan areas upward on the composite index but are accompanied by environmental and infrastructure constraints. In resource-rich regions, a “dual gap” is confirmed: rapid economic growth alongside lagging environmental quality and social infrastructure. Thus, Kazakhstan’s pattern fits within the international picture while exhibiting its own emphases: a more pronounced role of southern demographic dynamics and a high dependence of several regions on commodity cycles.

A methodological comparison reinforces the added value of the proposed RHCI relative to the HDI and HCI. While the HDI captures long-term development outcomes across three dimensions and applies normative thresholds with geometric aggregation, it is designed exclusively for national-level comparisons and does not reflect spatial heterogeneity within countries. The HCI, in turn, focuses on the expected productivity of future workers, emphasizing years of schooling and health-adjusted survival, but similarly lacks subnational resolution and does not account for demographic pressure or environmental constraints.

In contrast, the RHCI expands the structure to four pillars—demographic, social, economic, and environmental—and integrates a significantly broader set of regionally measurable indicators. This allows the index to capture the mechanisms through which human capital is formed, realized, and conditioned by territorial externalities. The RHCI therefore complements global indices by translating their conceptual foundations into a spatially explicit, region-focused analytical framework that is essential for policy design in countries with pronounced regional disparities such as Kazakhstan.

5.3. Implications for Regional Policy

The results point to the need to move away from one-size-fits-all measures toward differentiated policies aligned with each region’s profile across the four subindices. A typological approach provides the most practical framework: for the “high/above-average” clusters, priorities are overheating prevention and ecological modernization; for the “average” cluster, the focus is on eliminating diagnosed bottlenecks in one or two subindices; for the “below-average/low” clusters, priorities are basic social infrastructure, demographic resilience, and the launch of primary economic drivers. Such stratification helps order interventions and target budgets without dissipating resources.

For agglomerations and leading regions, “smart growth” instruments are appropriate: density and mobility management (public transport, mixed-use development), standards for urban environmental and air quality, green regulations for industry and construction, and front-loaded investments in education and health quality. This strategy helps retain human capital and weaken the negative correlation between the composite index and the environmental subindex via technological and environmental upgrades rather than administrative curbs.

For resource-rich regions, the central task is diversification and localization of value chains: incentives for non-resource industries and oil-and-gas services, development of applied R&D and engineering skills, and modernization of environmental practices and monitoring. The strong economic pillar must be converted into durable social returns through targeted programs in primary healthcare, preschool and school education, and settlement/housing infrastructure for skilled workers.

For the southern “demographic-growth” regions, the priority is rapid conversion of quantitative population gains into human-capital quality. This implies accelerated expansion of preschool and school places; development of vocational education, dual programs, and early career guidance; support for female employment and care services. In the short run, logistical bottlenecks (transport, digital connectivity) should be addressed; in the medium term, job creation in manufacturing and modern services is needed to reduce risks of disguised unemployment and migration outflows.

For the industrial belt of the central–northern zone, retaining and renewing the labor force, reducing environmental loads, and improving urban environmental quality are critical. Effective bundles include reskilling programs and incentives to attract young specialists; targeted support for families with children; brownfield redevelopment with environmental remediation; and cultivation of high-tech niches within traditional sectors. For northern and parts of eastern regions with aging populations, policy should foster in-migration, expand access to core services, and upgrade the attractiveness of small and medium-sized cities as growth nodes.

Four cross-cutting blocks are common to all clusters. First, component balance: economic stimuli must be co-designed with binding commitments on social infrastructure, demography, and ecology; otherwise, gains in the composite index will be short-lived. Second, management by objectives and data: annual monitoring of subindices via public dashboards and GIS maps; matrix-style KPIs for regional programs (one key driver indicator per subindex); and a rule whereby priorities are automatically revised after evaluation. Third, institutional coordination: alignment of national, regional, and municipal instruments (budgets, grants, standards) and structured business participation via green investment agreements and social compacts. Fourth, financial architecture: use of conditional, purpose-tied transfers and competitive funds for projects that raise weak subindices; issuance of green and social bonds for infrastructure packages; and pay-for-results mechanisms where impacts are measurable.

The sequencing of implementation should follow the logic “bottlenecks first, multipliers next.” In low-performing regions, basic services and demographic incentives come first; in “average” regions, targeted investment in weak components; for leaders, quality retention, environmental upgrades, and innovation. This trajectory reduces interregional polarization, raises returns on public spending, and shifts human-capital growth from an extensive path to a sustainable, quality-driven one.

Results are sensitive to indicator selection, normalization/weighting procedures, and the retrospective alignment to end-period administrative boundaries. The 2020 cross-section partly reflects pandemic shocks. Correlations describe joint variation rather than causal links; endogeneity is possible (e.g., economic growth and migration reinforce each other). These limitations were acknowledged in interpretation and do not change the main conclusions, but they underscore the need for regular updates and an expanded indicator base.

Further work should move from descriptive diagnostics to causally informed estimates and explicit spatial effects: employ panels with quasi-experimental designs and embed spatial econometrics to account for spillovers. Priority should be given to enriching the indicator base with outcome metrics (education, health, environmental quality) validated against administrative registries and remote-sensing data. Systematic sensitivity checks to normalization, weights, and aggregation are needed, along with formal uncertainty intervals. In parallel, the scale of analysis should be deepened to districts/urban districts with explicit treatment of migration and population heterogeneity. Finally, scenario assessments for 2030–2050 and routine public monitoring (dashboards and GIS), under a rule whereby priorities are revised following evaluation, will enable timely recalibration of policy priorities.

6. Conclusions

The study develops a reproducible methodology for the subnational assessment of human capital in Kazakhstan and documents persistent interregional heterogeneity in levels and dynamics over 2000–2020. The results confirm that the composite indicator is most sensitive to the economic subindex, whereas the demographic and social components shape the long-run trajectory of human-capital accumulation, and the environmental component acts as a constraint in industry-intensive and agglomeration economies. Combining cartographic analysis with an index-based approach enabled a shift from simple ranking to an interpretation of the spatial structure of disparities and the identification of regional types with distinct deficit profiles.

The practical value lies in the direct embedment of the composite assessment into strategic planning and SDG monitoring. For leading regions, the priority is the “fine-tuning” of the investment mix: sustaining education and health quality, raising returns to R&D, and green modernization of infrastructure to prevent an environmental-subindex bottleneck. For regions with average index values, the priority is to eliminate one or two diagnosed bottlenecks—typically deficits in access to social services and selective shortfalls in demographic indicators—through targeted instruments: expanding capacity in preschool and primary education, disease-prevention programs, upskilling teachers and physicians, and improving transport and digital access to core services. For vulnerable territories—where economic and demographic weaknesses coincide—baseline equalization measures are required: a guaranteed package of social infrastructure, employment stimulation and youth retention, and minimum service-quality standards regardless of distance to the regional center; environmental constraints should be incorporated at early design stages to avoid locking in technologically outdated solutions.

The findings also have implications for climate-resilient development. Regions with industry-intensive profiles and metropolitan agglomerations demonstrate persistent environmental pressures, indicating that human-capital-oriented strategies should be integrated with national climate-governance frameworks. Strengthening air-quality regulation, promoting green infrastructure, and aligning regional investment programs with Kazakhstan’s low-carbon commitments are critical for mitigating long-term environmental constraints that directly affect human capital formation.

The proposed index should serve as a platform for regular public monitoring aligned with the annual budget cycle. In operational terms, this implies: deploying a dashboard with subindex maps and time series; setting transparent thresholds for policy triggers (e.g., automatic inclusion in targeted support if a region remains “below average” for two consecutive years); linking intergovernmental transfers and infrastructure investments to observed deficit profiles; and integrating results into regional human-capital programs with measurable three-year targets. Closing the loop between analytics and budgeting reduces the lag between diagnosis and intervention and establishes a basis for effectiveness evaluation.

Study limitations relate primarily to the constraints of the indicator system, the retrospective nature of regional statistics, and the limited availability of outcome-level metrics. Although the study incorporates correlation analysis, global Moran’s I, and a full sensitivity assessment (weighting, normalization, indicator-exclusion tests), several methodological extensions remain beyond the scope of the present work and represent directions for further research.

First, the composite RHCI is sensitive to the structure of the indicator set: enriching the database with direct measures of learning outcomes, health quality, and environmental conditions would increase diagnostic precision. Second, while global spatial autocorrelation was assessed, advanced spatial-econometric modeling (e.g., SAR, SEM, SLX) was not implemented; these models would allow quantifying spillover effects and disentangling causal interactions between neighboring regions. Third, using regional data limits the granularity of analysis: extending the RHCI to the district/urban-district scale would provide deeper insight into intra-regional heterogeneity. Finally, post-2020 data were not included due to methodological discontinuities, COVID-19-related structural shocks, and administrative reforms; the construction of a fully harmonized post-2020 time series is a necessary next step for longitudinal extension.

Although the empirical material is rooted in Kazakhstan, the methodological contribution of this study is universal. The RHCI offers a structured, transparent, and reproducible approach to assessing territorial human capital that can be applied in other national contexts as a diagnostic, comparative, and policy-oriented tool. Kazakhstan in this article functions as a test case validating its operational feasibility and demonstrating its analytical value. Future research may extend the RHCI methodology to other Central Asian countries or adapt it to broader international comparisons.

Overall, the primary contribution of this study lies in advancing a coherent methodological framework for subnational human-capital assessment rather than in generating country-specific policy prescriptions. By integrating a composite index, spatial analytics, and diagnostic typologies within a reproducible structure, the study provides new conceptual and empirical tools for interpreting territorial disparities. Kazakhstan serves as an illustrative case demonstrating how the framework operates in practice, while the methodological logic is transferable to broader comparative and theoretical research.

Beyond Kazakhstan, the findings carry broader implications for global debates on human-capital-driven development. Many countries exhibit similar spatial divides, where leading regions accumulate human capital and peripheral areas face demographic decline, aging, and weaker educational and health infrastructures. The patterns identified here mirror global evidence from Europe, China, and Latin America, where subnational disparities exceed cross-country differences. Therefore, Kazakhstan’s regional trajectory reflects a wider challenge: achieving sustainable development requires territorially differentiated human-capital strategies embedded within climate-resilient, environmentally responsible growth models.

Taken together, the findings indicate that human-capital policy must be differentiated, scenario-based, and environmentally responsible. Regular recomputation of the index and its disaggregation to the regional level create the conditions for targeted prioritization and the progressive narrowing of interregional gaps, consistent with the goals of sustainable and inclusive growth. The study provides a methodological foundation and a set of practical instruments for integration into the regional planning circuit, and it outlines a research roadmap to increase the validity and applied usefulness of the assessment.