Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) Protocols Used in Carbon Trading Applied to Dryland Nations in the Global South for Climate Change Mitigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Defining MRV Protocols

- (1)

- Monitoring: This involves using scientific methods and models to quantify the amount of CO2 removed by a project, and includes techniques appropriate for the specific carbon removal method.

- (2)

- Reporting: The measured data are compiled and reported according to established protocols, including detailed information about the project, methodology, and results.

- (3)

- Verification: A third-party verifier assesses the project’s data and methodology to ensure it meets the requirements of the specific MRV protocol, which includes an independent validation of carbon removal claims.

1.2. Background to MRVs

1.3. 2006 IPCC Guidelines

1.4. Rationale and Research Question

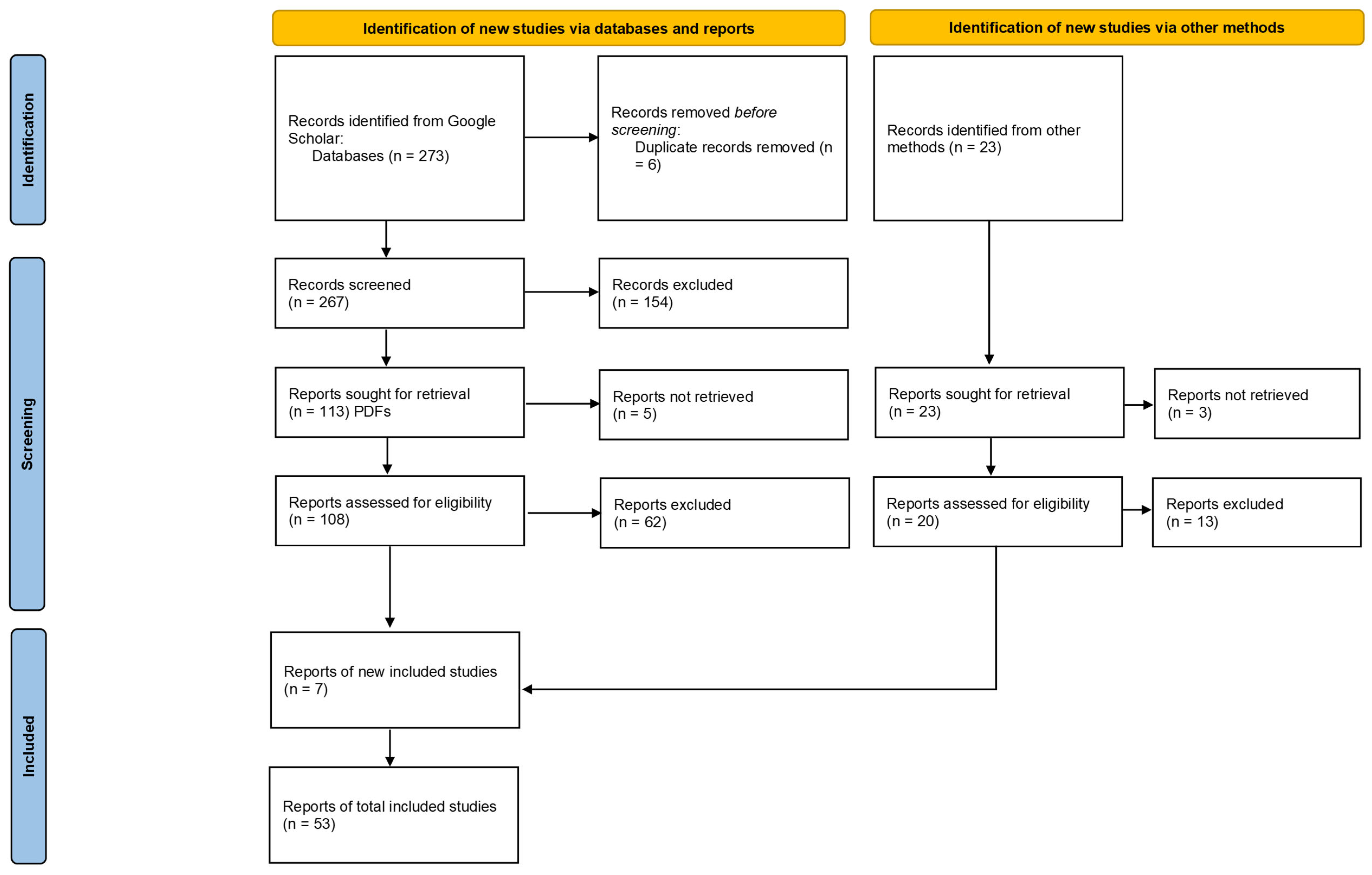

2. Materials and Methods

- “carbon sequestration” AND “agricultural land” AND “climate change mitigation” AND “Global South” AND “arid land” OR drylands.

3. Results

3.1. Challenges of SOC MRV Protocols and Some Suggestions for Improvement

3.1.1. Monitoring

- LBC, PVivo—discount tillage information.

- CFT, PVivo, the IPCC-based version of GStdmod—do not include crop rotation; the complexity of the rotation, together with the yield of each crop.

- GStdmod, CFI, PVivo—cover crops are not explicitly required to model SOC changes.

3.1.2. Reporting

3.1.3. Verification

3.2. The Case for Egypt

3.2.1. Egypt’s National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS) 2050

3.2.2. Egypt’s Second Updated Nationally Determined Contributions

3.2.3. First Biennial Update Report (BUR) and Fourth National Communication

- Direct N2O emissions—from agricultural soils, including nitrogen-fixing crops, crop residues, fertilizers, and animal waste;

- Direct N2O emissions—soil emissions from livestock production; and

- Indirect N2O emissions—runoff, nitrogen leaching, and volatilization from agricultural activities.

3.2.4. Egypt’s Carbon Trading Regulations and Guidelines

3.3. Lessons from (Other) Nontropical Dryland Nations

3.3.1. African Countries

3.3.2. China

3.3.3. India

4. Discussion

4.1. Improvements in the Global South

4.1.1. Improving SOC MRV Methods

4.1.2. Further Considerations for Dryland Regions

4.2. Contributions

4.2.1. Economic Viability of Carbon Projects in Arid Regions

4.2.2. Recommendations and Future Directions

- (1)

- Adopting AI technologies to automate the process to a fully integrated system requires building an end-to-end digital infrastructure. Investments are already being made by Verra with its registry digitalization that uses built-in algorithms to automate calculations. Such developments establish Verra as the leading GHG crediting program (https://verra.org/programs/verified-carbon-standard/, accessed on 9 July 2025).

- (2)

- Other suggestions are AI-optimized sampling point layouts, AI-automated and online accessible data entry (besides project registration), and enhanced reporting standardization.

- (3)

- Policy tools could be further deployed, such as carbon tax revenue reinvestment, to reduce MRV costs.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Most of the challenges for MRV protocols are in the monitoring phase of MRV protocols, and to a lesser extent, in reporting and verification. These challenges stem from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to measurements evident in current monitoring methods. Greater attention needs to be directed toward an international protocol that considers the global climate and its impact on the distribution of soils with different SOC content.

- (2)

- As demonstrated by the case for Egypt, although there are national-international attempts at addressing agriculture (and agricultural soils) within climate change strategies, VCMs need better integration into private-public legislative frameworks that help increase awareness among end-users and provide initial funding support to allow smallholder farmers to participate alongside large (commercial) farms.

- (3)

- MRV protocols are currently executed with assistance from nonprofits, and in some cases aggregation to the community level is required to make the process feasible. An end-to-end, accessible digital framework, with project developers set in motion to guide end-users through the entire process, may encourage more participation, especially in developing countries where carbon trading has only recently been introduced. Farmers turn to carbon programs like Verra because of its well-defined methodology and the direction it provides to end users.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFOLU | Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use |

| BEE | Bureau of Energy Efficiency |

| BUR | Biennial Update Report |

| CDR | Carbon dioxide removal |

| CERC | Carbon Emission Reduction Certificate |

| CERP | Carbon Emission Reduction Project |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| COMET | CarbOn Management Evaluation Tool |

| COP26 | The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference |

| CWANA | Central and West Asia and North Africa |

| DNDC | DeNitrification-DeComposition |

| EGX | Egyptian Stock Exchange |

| ESM | Equivalent soil mass calculation |

| ETF | Enhanced Transparency Framework |

| ETS | Emissions trading scheme |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FD | Fixed-depth |

| FRA | Financial Regulatory Authority |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| ICM | Indian Carbon Market |

| ICROA | International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa region |

| MIR | Mid infrared |

| MoEFCC | Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change |

| MRV | Monitoring, reporting, and verification |

| NAPCC | National Action Plan on Climate Change |

| NCCS | National Climate Change Strategy |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| NGOs | Nongovernmental organization |

| N2O | Nitrous oxide |

| NRCS | Natural Resources Conservation Service |

| NRT | Northern Rangeland Trust |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PEG | Private environmental governance |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SADS | Sustainable Agricultural Development Strategy |

| SAIL | Sustainable Agriculture Investments and Livelihoods |

| SLM | Sustainable Land Management |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| VCM | Voluntary Carbon Market |

| VCS | Verified Carbon Standard |

References

- Ingemarsson, M.L.; Wang-Erlandsson, L. Mitigation Measures in Land Systems; Stockholm International Water Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Everhart, S. Growing Carbon Credits: Strengthening the Agricultural Sector’s Participation in Voluntary Carbon Markets through Law and Policy. NYU Environ. Lett. J. 2023, 65, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Regulatory Authority Understanding the New Carbon Credit Trading Regulations in Egypt. Available online: https://shehatalaw.com/law-update/new-regulations-carbon-certificates/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Environmental Defense Fund. Agricultural Soil Carbon Credits: Making Sense of Protocols for Carbon Sequestration and Net Greenhouse Gas Removals; Environmental Defense Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, N.; Fuss, S.; Buck, H.; Schenuit, F.; Pongratz, J.; Schulte, I.; Lamb, W.F.; Probst, B.; Edwards, M.; Nemet, G.F.; et al. The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal, 2nd ed.; OSF: Peoria, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Batjes, N.H.; Ceschia, E.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Demenois, J.; Le Maire, G.; Cardinael, R.; Arias-Navarro, C.; Van Egmond, F. Towards a Modular, Multi-Ecosystem Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) Framework for Soil Organic Carbon Stock Change Assessment. Carbon Manag. 2024, 15, 2410812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, H.; Ernsting, A.; Semino, S.; Gura, S.; Lorch, A. Agriculture and Climate Change: Real Problems, False Solutions; Food and Agriculture Organization: Bangkok, Thailand, 2009; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Wissner, N.; Schneider, L.; Jung, H.; Orozco, E.H.; Kwamboka, E.; Johnson, F.X.; Bößner, S. Sustainable Development Impacts of Selected Project Types in the Voluntary Carbon Market; Oeko-Institut e.V.: Freiburg, Germany, 2022; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Dongre, D.; Jendre, A.; Mohanty, L.K.; Pradhan, K.; Wani, R.A.; Ashish, R.; Panotra, N.; Bhojani, S.H.; Soni, V.; Upadhyay, L. The Economics of Carbon Sequestration and Climate Change Mitigation Potential of Different Soil Management Practices. Arch. Curr. Res. Int. 2025, 25, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, A. A Review of Research on Farmers’ Perspectives and Attitudes Towards Carbon Farming as a Climate Change Mitigation Strategy; Urban and Rural Reports; Department of Urban and Rural Development, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2024; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, S.; Janoski, K. Economic Considerations for the Development of a Carbon Farming Scheme; Burleigh Dodds Series in Agricultural Science; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 809–828. ISBN 978–1-78676-969-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.A.; Eash, L.; Polussa, A.; Jevon, F.V.; Kuebbing, S.E.; Hammac, W.A.; Rosenzweig, S.; Oldfield, E.E. Testing the Feasibility of Quantifying Change in Agricultural Soil Carbon Stocks through Empirical Sampling. Geoderma 2023, 440, 116719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, P.; Spertus, J.; Chiartas, J.; Stark, P.B.; Bowles, T. Valid Inferences about Soil Carbon in Heterogeneous Landscapes. Geoderma 2023, 430, 116323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Collier, S.; Baldock, J.; Burgess, R.; Creque, J.; DeLonge, M.; Dungait, J.; Ellert, B.; Frank, S.; Goddard, T.; et al. Quantifying Carbon for Agricultural Soil Management: From the Current Status toward a Global Soil Information System. Carbon Manag. 2019, 10, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potash, E.; Bradford, M.A.; Oldfield, E.E.; Guan, K. Measure-and-Remeasure as an Economically Feasible Approach to Crediting Soil Organic Carbon at Scale. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 024025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Eagle, A.J.; Rubin, R.L.; Rudek, J.; Sanderman, J.; Gordon, D.R. Crediting Agricultural Soil Carbon Sequestration. Science 2022, 375, 1222–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, S.; Pronger, J.; Goodrich, J.; Allen, K.; Graham, S.; McNeill, S.; Roudier, P.; Norris, T.; Barnett, A.; Schipper, L.; et al. Reconciling Historic and Contemporary Sampling of Soil Organic Carbon Stocks: Does Sampling Approach Create Systematic Bias? Geoderma 2025, 458, 117338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffeld, A.M.; Bradford, M.A.; Jackson, R.D.; Rath, D.; Sanford, G.R.; Tautges, N.; Oldfield, E.E. The Importance of Accounting Method and Sampling Depth to Estimate Changes in Soil Carbon Stocks. Carbon Balance Manag. 2024, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupla, X.; Bonvin, E.; Deluz, C.; Lugassy, L.; Verrecchia, E.; Baveye, P.C.; Grand, S.; Boivin, P. Are Soil Carbon Credits Empty Promises? Shortcomings of Current Soil Carbon Quantification Methodologies and Improvement Avenues. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.; Paustian, K. Importance of On-Farm Research for Validating Process-Based Models of Climate-Smart Agriculture. Carbon Balance Manag. 2024, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnert, M.; Vetter, S.H.; Smith, P.; Institute of Biological & Environmental Sciences, University of Aberdeen, UK Measuring and Monitoring Soil Carbon Sequestration. Burleigh Dodds Series in Agricultural Science; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 305–322. ISBN 978-1-78676-969-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, C.; Black, C.K.; Segal, B.D.; Gurung, R.B.; Zhang, Y.; Easter, M.J.; Williams, S.; Motew, M.; Campbell, E.E.; Brummitt, C.D.; et al. Validating DayCent-CR for Cropland Soil Carbon Offset Reporting at a National Scale. Geoderma 2023, 438, 116647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, B. Life Cycle Assessment in the Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification of Land-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal: Gaps and Opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11950–11963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, F.; Baumüller, H.; Ecuru, J.; von Braun, J. Carbon Farming in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges for Engaging Smallholder Farmers; ZEF Working Paper Series, No. 221; University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF): Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderman, J.; Savage, K.; Dangal, S.R.S.; Duran, G.; Rivard, C.; Cavigelli, M.A.; Gollany, H.T.; Jin, V.L.; Liebig, M.A.; Omondi, E.C.; et al. Can Agricultural Management Induced Changes in Soil Organic Carbon Be Detected Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy? Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batjes, N.H. Total Carbon and Nitrogen in the Soils of the World. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1996, 47, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.; Jenkinson, D.S. RothC-26.3—A Model for the Turnover of Carbon in Soil. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models; Powlson, D.S., Smith, P., Smith, J.U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 237–246. ISBN 978-3-642-64692-8. [Google Scholar]

- Amelung, W.; Bossio, D.; De Vries, W.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Lehmann, J.; Amundson, R.; Bol, R.; Collins, C.; Lal, R.; Leifeld, J.; et al. Towards a Global-Scale Soil Climate Mitigation Strategy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, L.; Burke, J. Strengthening MRV Standards for Greenhouse Gas Removals to Improve Climate Change Governance; Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment: London, UK, 2023; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, L.; Burke, J.; Rodway-Dyer, S. Towards Improved Cost Estimates for Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Carbon Dioxide Removal; Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lou, R.; Qi, Z.; Madramootoo, C.A.; He, Y.; Jiang, Q. Optimization Strategies for Carbon Neutrality in a Maize-Soybean Rotation Production System from Farm to Gate. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 50, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Arcas, R.; Alghamdi, A.; Alharethi, M.; Aldoukhi, M. Carbon Markets, International Trade, and Climate Finance. Trade Law Dev. 2025, 16, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Lavallee, J.M.; Kyker-Snowman, E.; Sanderman, J. The Need for Knowledge Transfer and Communication among Stakeholders in the Voluntary Carbon Market. Biogeochemistry 2022, 161, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Qian, X.; Zhou, W. Transition to a Multi-Dimensional Carbon Emission Data Quality Assurance Scheme: Analysis Based on MLP Theory. Policy Sci. 2025, 42, 745–767. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelaty, H.; Weiss, D.; Mangelkramer, D. Climate Policy in Developing Countries: Analysis of Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Measures in Egypt. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyptian Environmental Affairs. Agency Summary for Policymakers: Egypt National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS) 2050; Egyptian Environmental Affairs; Agency: Giza, Egypt, 2022; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Egypt’s Updated Nationally Determined Contributions. 2023. p. 46. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2023-06/Egypts%20Updated%20First%20Nationally%20Determined%20Contribution%202030%20%28Second%20Update%29.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Tantawi, S. Egypt’s First Biennial Transparency Report. 2024. p. 299. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Egypt%20BTR1%20Final%20Master%20Report_v3_30DEC24%20AMR.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Lamboll, R.; Nelson, V.; Nathaniels, N. Emerging Approaches for Responding to Climate Change in African Agricultural Advisory Services: Challenges, Opportunities and Recommendations for an AFAAS Climate Change Response Strategy; African Forum for Agricultural Advisory Services: Kampala, Uganda, 2011; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Wattel, C.; Negede, B.; Desczka, S.; Pamuk, H.; van Asseldonk, M.; Castro Núñez, A.; Amahnui Amenchwi, G.; Borda Almanza, C.A.; Vanegas Cubillos, M.; Marulanda, J.L.; et al. Finance for Low-Emission Food Systems—Six Financial Instruments with Country Examples; CGIAR Research Initiative for Low-Emission Food Systems, Wageningen Economic Research; CGIAR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2024; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, S.; Wang, W. Overview of Climate Change Policies and Development of Emissions Trading in China; Information and Debates Series; Chaire Economie du Climat: Paris, France, 2014; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. Carbon Pricing Induces Innovation: Evidence from China’s Regional Carbon Market Pilots. AEA Pap. Proc. 2018, 108, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Ye, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Addressing Climate Change through a Market Mechanism: A Comparative Study of the Pilot Emission Trading Schemes in China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Law, Y.K.; Fong, C.S. Emerging Markets’ Carbon Pricing Development: A Comparative Analysis of China and South Korea’s Experience. World 2025, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, N.; Kumar, R.K. A Study on Carbon Credits Trading in Indian Context. Int. J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, A.; Keen, S.; Rennkamp, B. A Comparative Analysis of Emerging Institutional Arrangements for Domestic MRV in Developing Countries; Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN): Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Saha, A.; Kumar, S.; Pathania, S. Regenerative Agriculture for Sustainable Food Systems; Kumar, S., Meena, R.S., Sheoran, P., Jhariya, M.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; ISBN 978-981-97-6690-1. [Google Scholar]

- Girish, G.D.; Trivedi, R. Monetising Carbon Credits: How Indian Farmers Can Benefit. Available online: https://idronline.org/article/agriculture/monetising-carbon-credits-how-indian-farmers-can-benefit/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Blaufelder, C.; Levy, C.; Mannion, P.; Pinner, D. Carbon Credits: Scaling Voluntary Markets; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Ghosh, A.; Garg, A.; Avashia, V.; Vishwanathan, S.S.; Gupta, D.; Sinha, N.K.; Bhushan, C.; Banerjee, S.; Datt, D.; et al. India’s Pathway to Net Zero by 2070: Status, Challenges, and Way Forward. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 112501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VM0042; VM0042: Improved Agricultural Land Management. Verra: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Verified Carbon Standard.

- Tanveer, U.; Ishaq, S.; Hoang, T.G. Enhancing Carbon Trading Mechanisms through Innovative Collaboration: Case Studies from Developing Nations. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 482, 144122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N. Addressing Scandals and Greenwashing in Carbon Offset Markets: A Framework for Reform. Glob. Transit. 2025, 7, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Jr., C.; Seabaurer, M.; Schwarz, B.; Dittmer, K.; Wollenberg, E. Scaling Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration for Climate Change Mitigation; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, B.; Lankoski, J.; Flynn, E.; Sykes, A.; Payen, F.; MacLeod, M. Soil Carbon Sequestration by Agriculture: Policy Options; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; Volume 174, p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Thornbush, M.J. Current Approaches in the Characterization and Quantification of Soil Crusts. In Advances in Agronomy; Advances in Agronomy Series; Elsevier Science & Technology: London, UK, 2025; Volume 192, pp. 185–250. ISBN 978-0-443-31440-7. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Dis/Advantages |

|---|---|

| Biogeochemical models | Include errors and uncertainty based on the assumptions used and underlying concepts [22] Need to be calibrated and validated, which requires data [22] |

| Ecosystem models | Enable larger scales, but models need to be unbiased and adequately predict SOC changes with known uncertainty [23] DayCent-CR version of the DayCent ecosystem model is a credit-ready version that meets some guidelines, e.g., Climate Action Reserve’s Soil Enrichment Protocol [23] |

| Hybrid approach | Modeling in DeNitrification-DeComposition (DNDC) with life cycle carbon Footprint showed reduced GHG emissions with agricultural residue utilization |

| Life cycle assessment (LCA) | LCA can provide critical insights into baselines, uncertainty, additionality, multifunctionality, holistic emission factors, overlooked carbon pools, and environmental safeguards [24] |

| Remote sensing | Including (1) spaceborne, (2) airborne, and (3) terrestrial remote sensing based on imagery acquired using various methods—e.g., satellites, airplanes, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) like drones, respectively [25] Nondestructive and can cover large areas, including those that are inaccessible, but can be limited to the first few cm of topsoil and measurements can be obscured by vegetation cover, and unable to measure belowground biomass [25] Low prediction accuracy of soil carbon, although it can be deployed as a collection of auxiliary data used for model-based estimates of carbon sequestration [25] |

| Mid infrared (MIR) spectroscopy | MIR spectroscopy has excellent performance in SOC measurement, e.g., root mean square error (RMSE) 0.10–0.33% across seven sites, with the same level of statistical significance (p < 0.10) for management effect using both laboratory-based % SOC and MIR estimated % SOC [26] Large existing MIR special libraries, e.g., United States Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS) Kellogg Soil Survey Laboratory MIR spectral library—can be operationalized for carbon monitoring [26] |

| Method | Cost | Scale | Spatial Resolution | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional direct sampling | Field, laboratory | Local–regional | High | High variance |

| Modeling | Software, experts | Local–global | Medium | Uncertainty |

| Remote sensing, incl. spectroscopy | Data access | Regional–global | Low | 30 cm depth |

| FRA Decree No. | Year | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 57 | 2023 | Establishes a Carbon Credits Supervision and Control Committee |

| 163 | 2023 | Lists entities that verify and attest to CERPs |

| 30 | 2024 | Sets standards for transparency, data security, and governance in accrediting voluntary carbon registries; ensures unique identification and traceability of each CERP |

| 31 | 2024 | Outlines the rules for listing/delisting and trading CERCS on the EGX |

| 1732 | 2024 | Outlines the conditions for brokerage firms to trade CERCs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thornbush, M.; Govind, A. Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) Protocols Used in Carbon Trading Applied to Dryland Nations in the Global South for Climate Change Mitigation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411001

Thornbush M, Govind A. Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) Protocols Used in Carbon Trading Applied to Dryland Nations in the Global South for Climate Change Mitigation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411001

Chicago/Turabian StyleThornbush, Mary, and Ajit Govind. 2025. "Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) Protocols Used in Carbon Trading Applied to Dryland Nations in the Global South for Climate Change Mitigation" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411001

APA StyleThornbush, M., & Govind, A. (2025). Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) Protocols Used in Carbon Trading Applied to Dryland Nations in the Global South for Climate Change Mitigation. Sustainability, 17(24), 11001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411001