Developing a Simulation-Based Traffic Model for King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Datasets and Methods

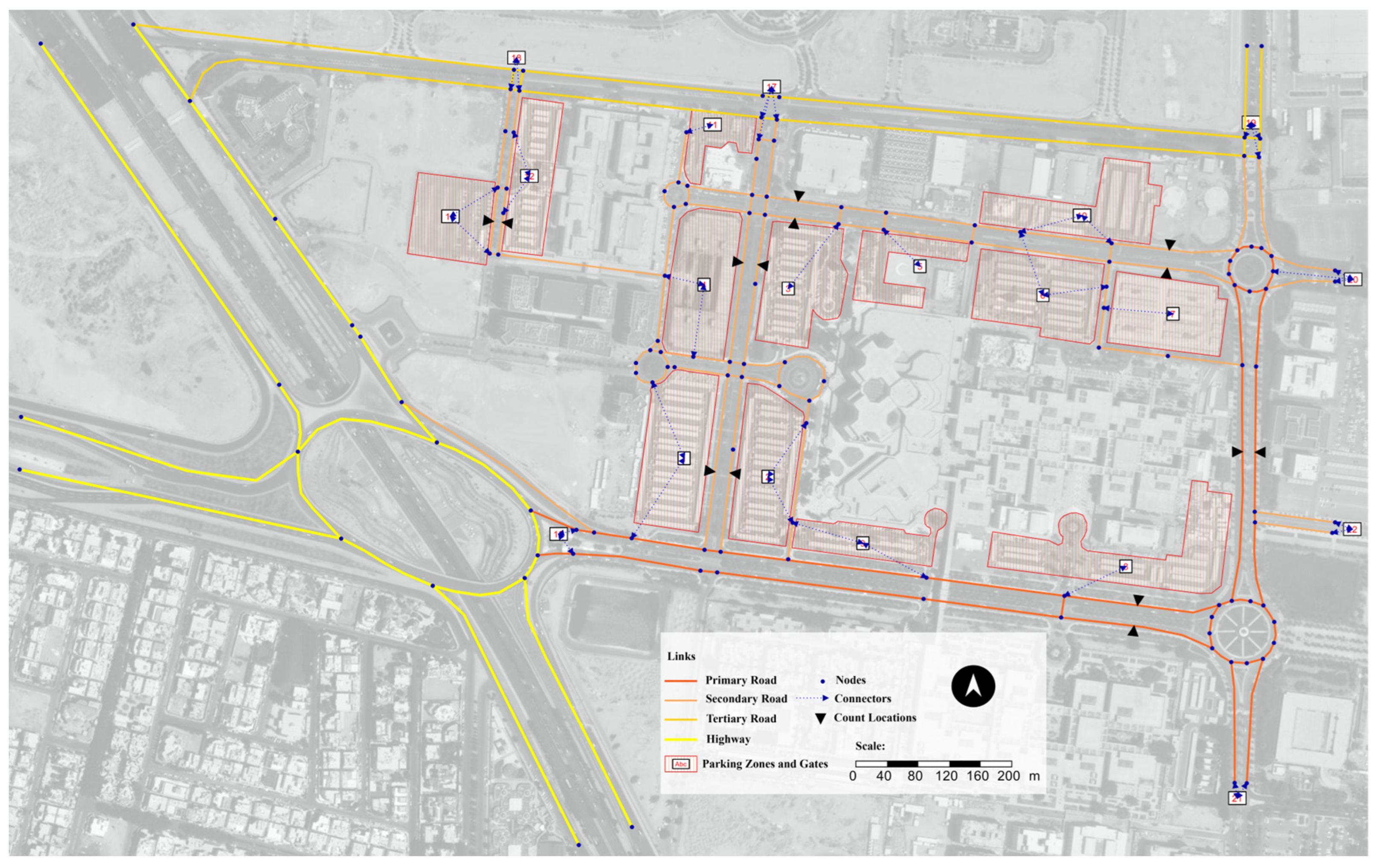

3.1. Data

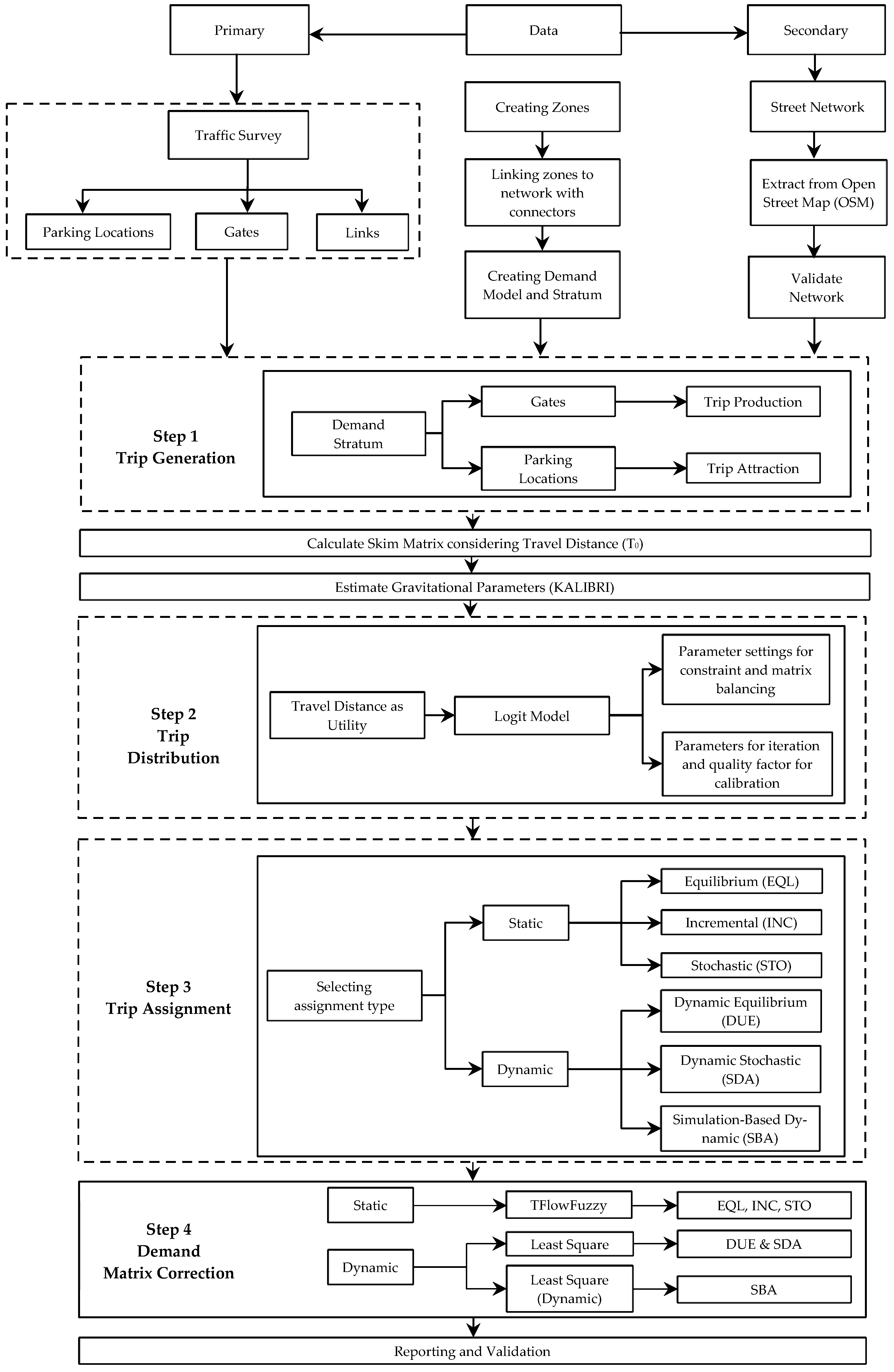

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Network Setup

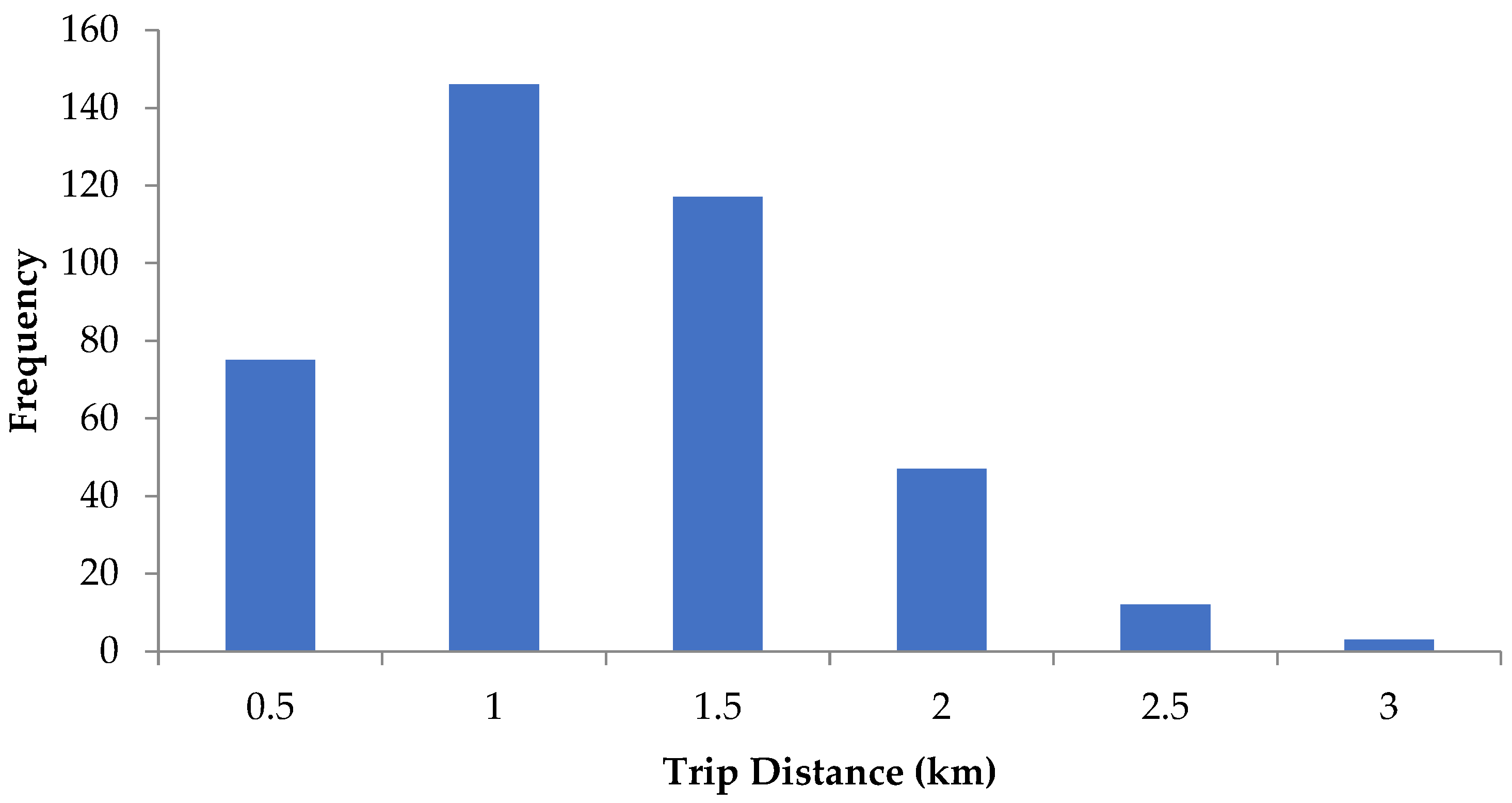

3.2.2. Trip Generation

3.2.3. Trip Distribution

3.2.4. Trip Assignment

- Static Traffic Assignment (STA)

- Dynamic Traffic Assignment (DTA)

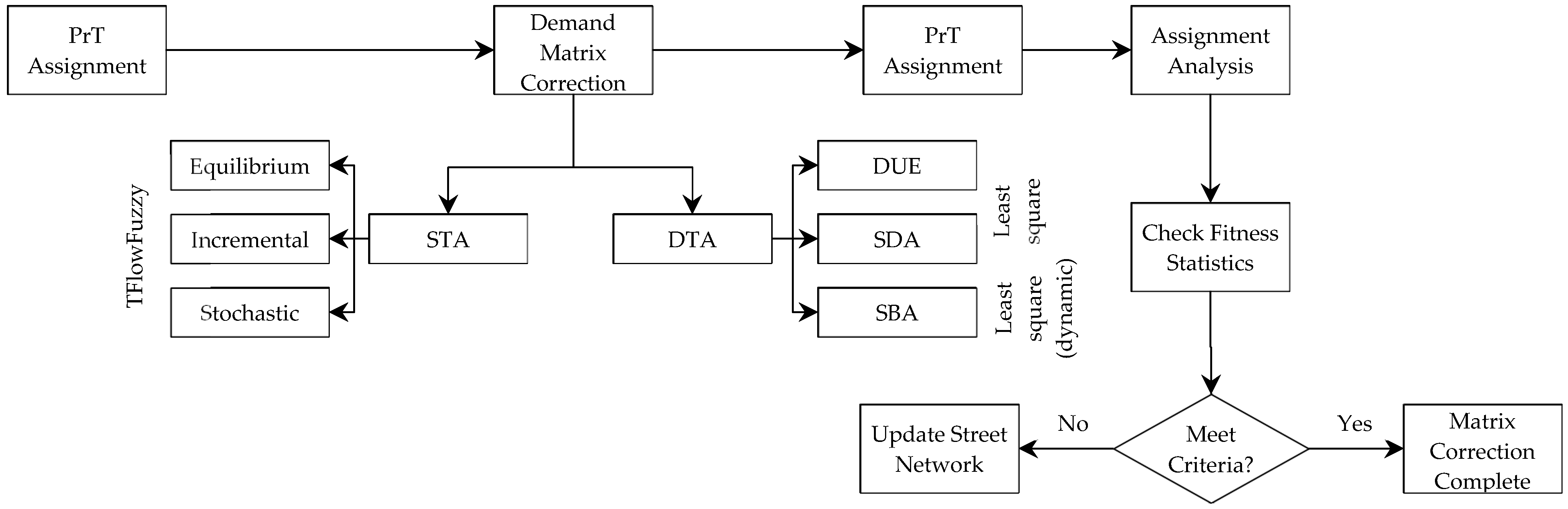

3.2.5. Origin–Destination Matrix Correction and Validation

4. Results

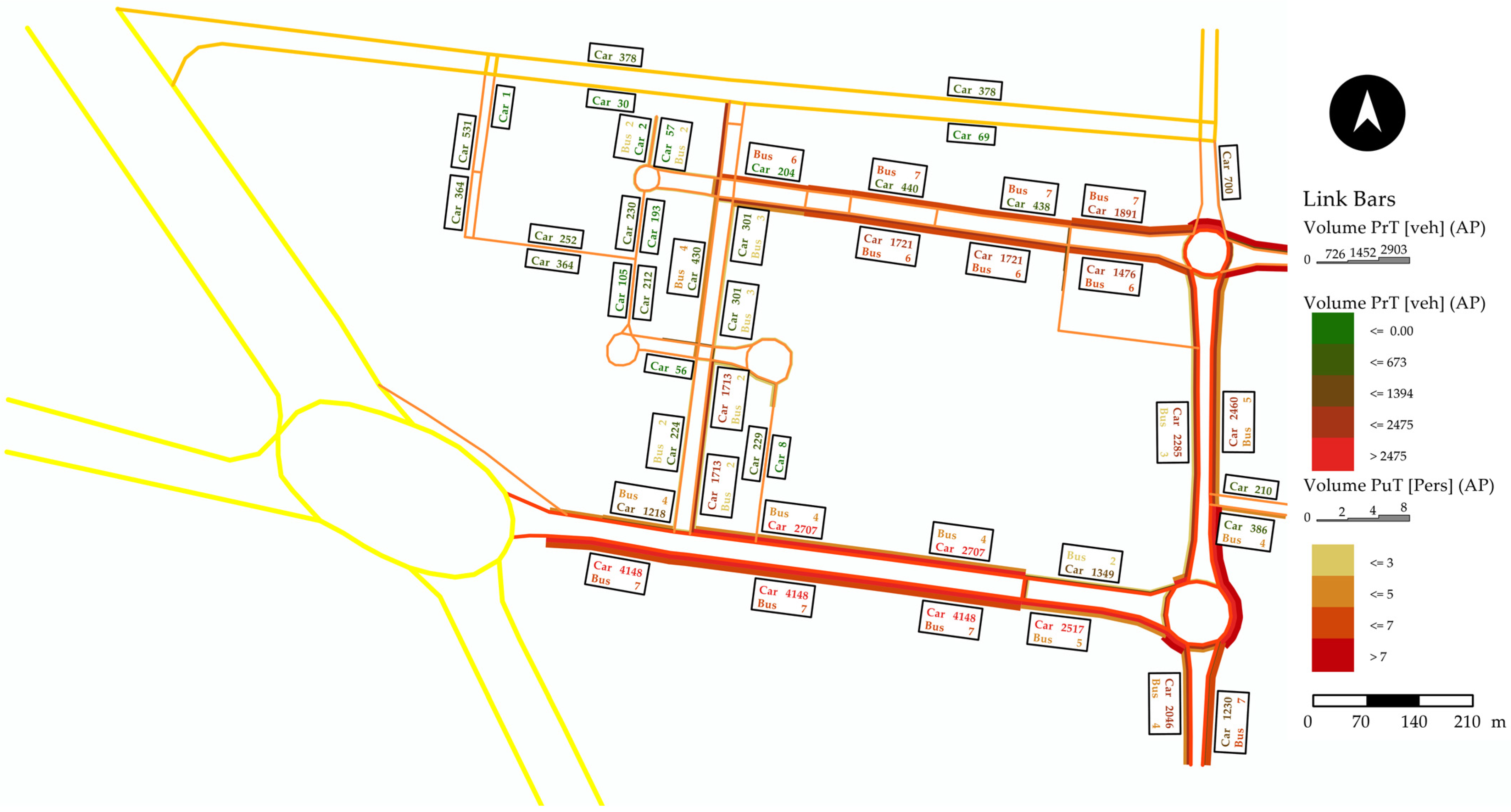

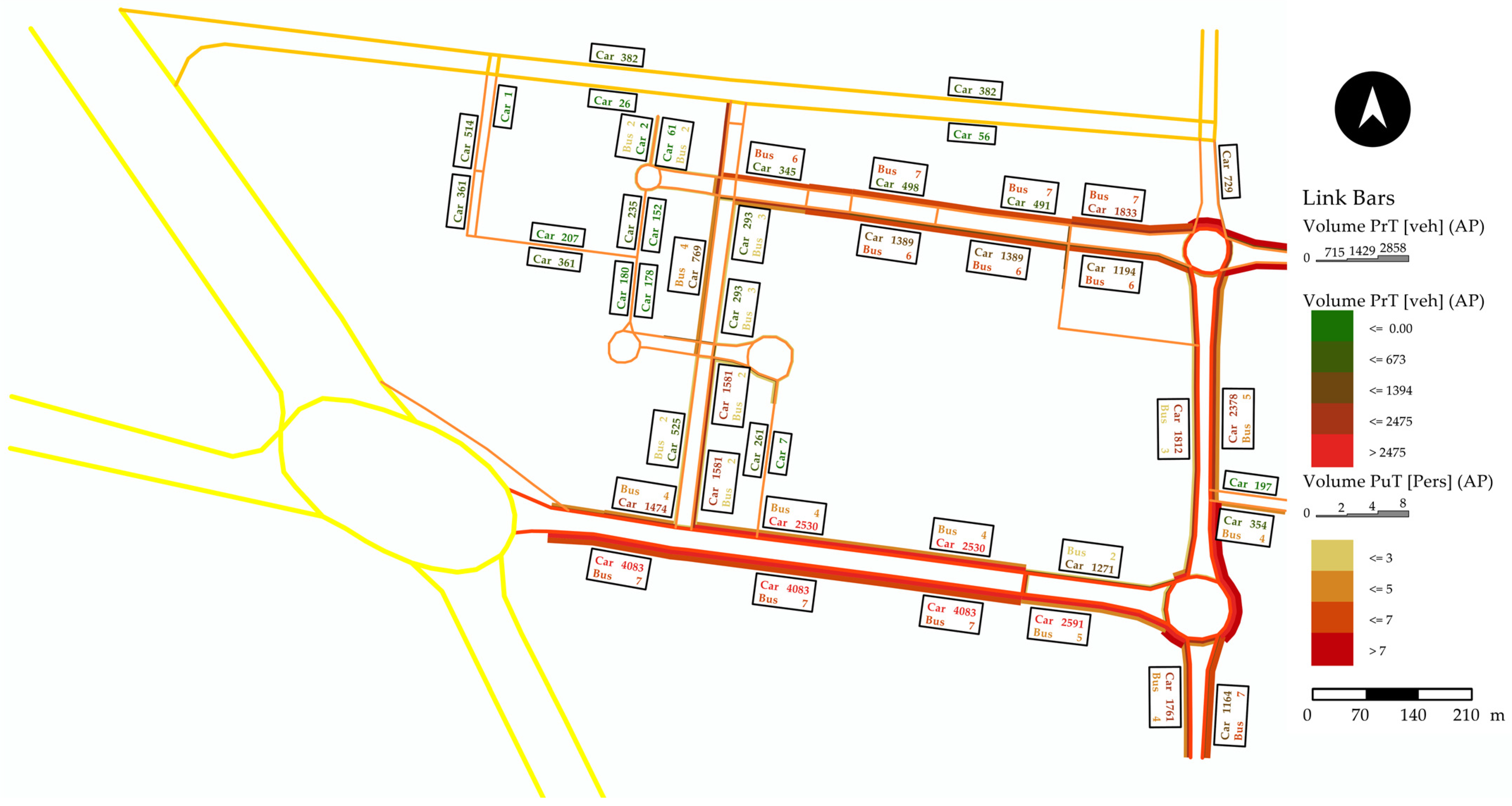

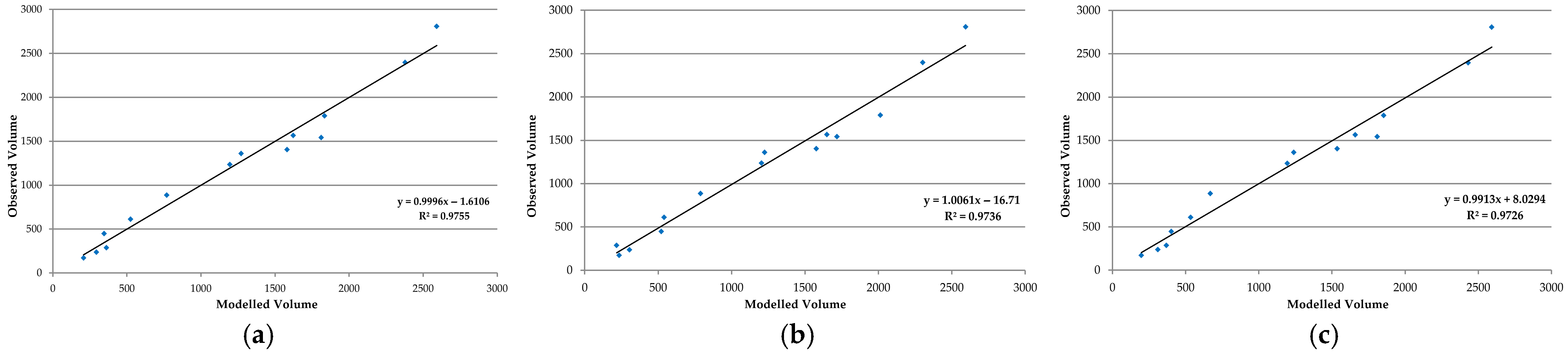

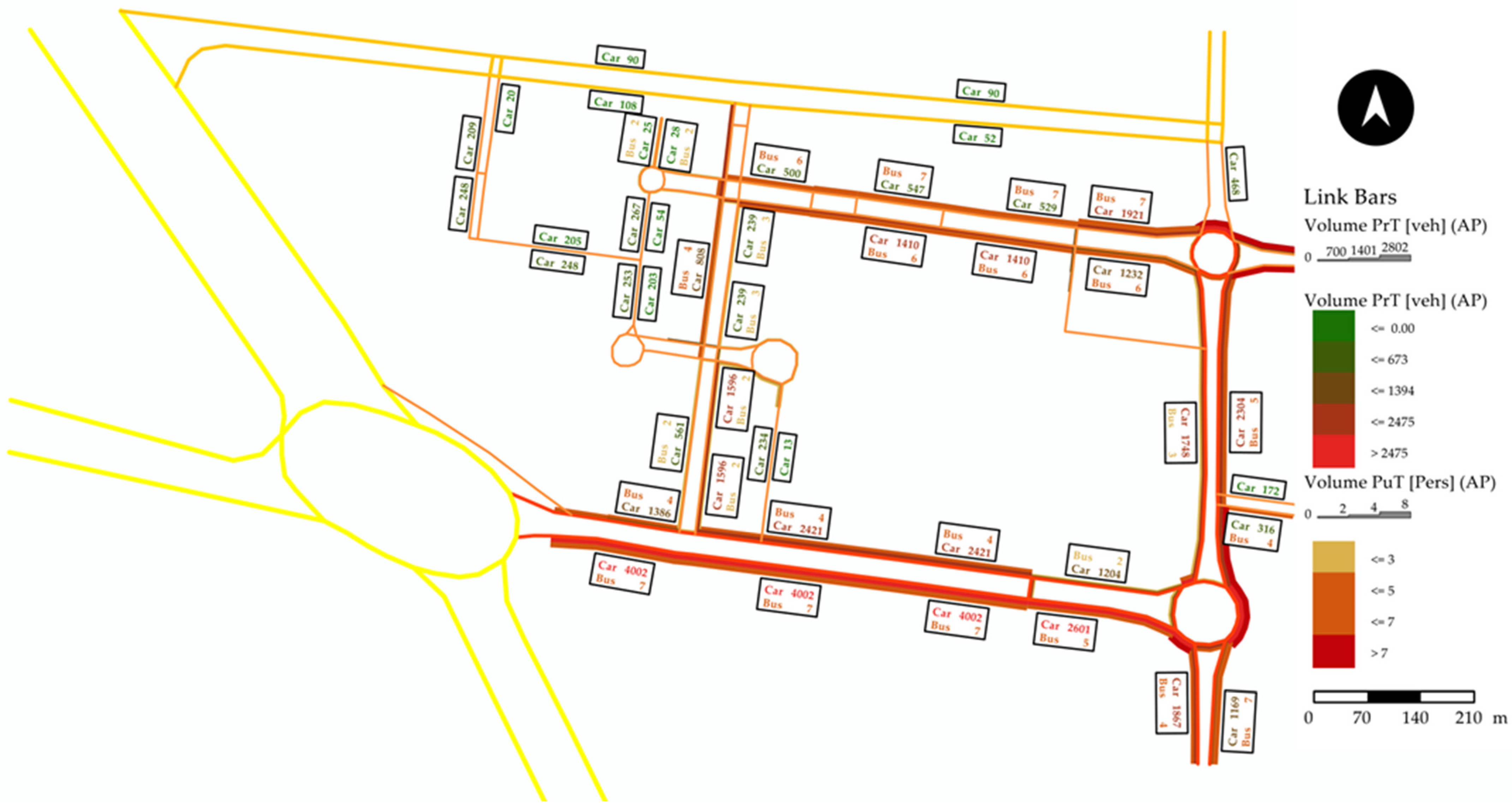

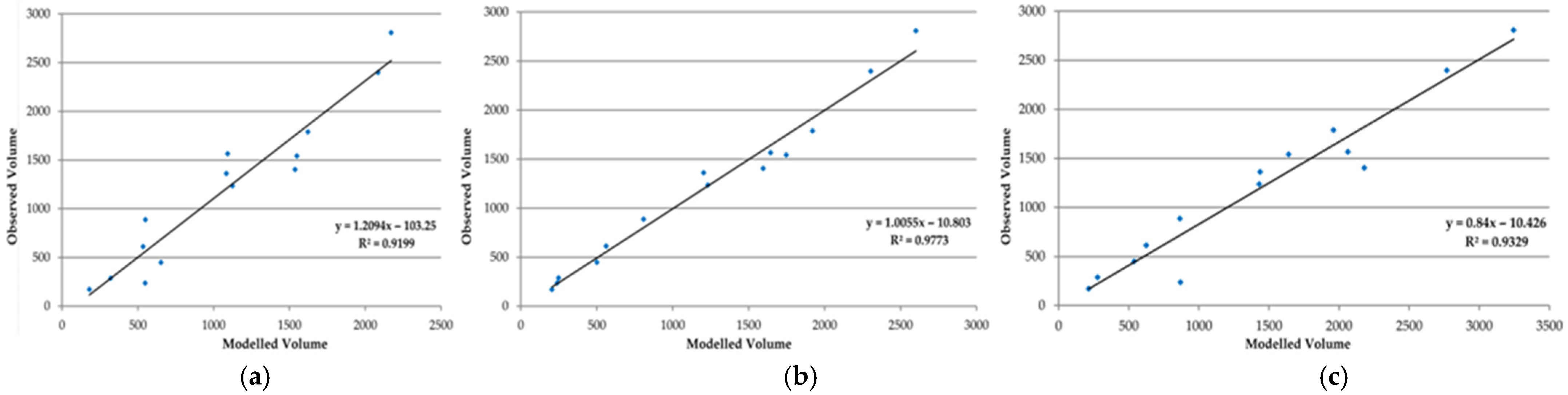

4.1. Static Traffic Assignments (STAs)

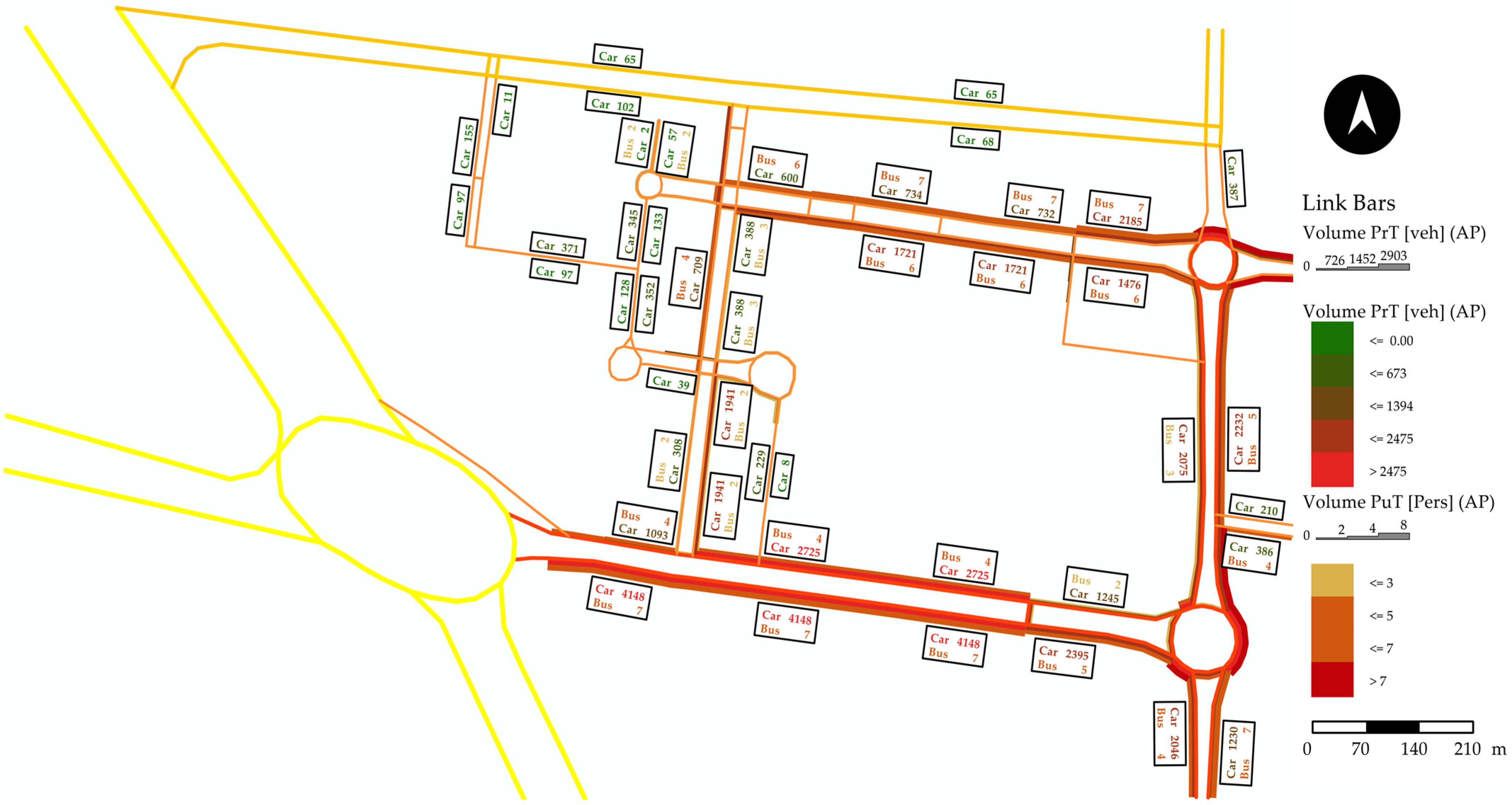

4.2. Dynamic Traffic Assignment (DTAs)

4.3. Comparative Evaluation of STAs and DTAs

5. Discussion, Limitation and Scope

6. Conclusions

- Use STA (EQL, followed by INC or STO if necessary) for baseline forecasting, scenario scoping, and rapid sensitivity testing.

- Apply SDA for operational design, including optimization of gate controls, signal timing, parking allocations, and scheduling adjustments during the 7:15–8:15 AM peak hour.

- Increase public transport usage by expanding bus frequency and routes to reduce private car dependence and improve network performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Station | Links | Observed Volume | Modelled Volume | Deviation (%) | GEH Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street Name | Direction | |||||

| S1 | Al Ehtifalat Street | EB | 2809 | 2395 | −15% | 8.1 |

| WB | 1362 | 1245 | −9% | 3.2 | ||

| S2 | Ali Al Murtada Street | SB | 1543 | 2075 | 26% | 12.5 |

| NB | 2398 | 2232 | −7% | 3.4 | ||

| S3 | Al-Malae’b Street | EB | 1789 | 2185 | 18% | 8.9 |

| WB | 1236 | 1476 | 16% | 6.5 | ||

| S4 | EB | 449 | 600 | 25% | 6.6 | |

| WB | 1566 | 2045 | 23% | 11.3 | ||

| S5 | Hospital Street | SB | 887 | 709 | −20% | 6.3 |

| NB | 238 | 388 | 39% | 8.5 | ||

| S6 | SB | 612 | 308 | −50% | 14.2 | |

| NB | 1404 | 1941 | 28% | 13.1 | ||

| S7 | Sahha Street | SB | 288 | 97 | −66% | 13.7 |

| NB | 172 | 371 | 54% | 12.1 | ||

| Station | Links | Observed Volume | Modelled Volume | Deviation (%) | GEH Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street Name | Direction | |||||

| S1 | Al Ehtifalat Street | EB | 2809 | 2517 | −10% | 5.7 |

| WB | 1362 | 1349 | −1% | 0.4 | ||

| S2 | Ali Al Murtada Street | SB | 1543 | 2285 | 32% | 17 |

| NB | 2398 | 2460 | 3% | 1.3 | ||

| S3 | Al-Malae’b Street | EB | 1789 | 1891 | 5% | 2.4 |

| WB | 1236 | 1476 | 16% | 6.5 | ||

| S4 | EB | 449 | 204 | −55% | 13.6 | |

| WB | 1566 | 1942 | 19% | 9 | ||

| S5 | Hospital Street | SB | 887 | 430 | −52% | 17.8 |

| NB | 238 | 301 | 21% | 3.8 | ||

| S6 | SB | 612 | 224 | −63% | 19 | |

| NB | 1404 | 1713 | 18% | 7.8 | ||

| S7 | Sahha Street | SB | 288 | 364 | 21% | 4.2 |

| NB | 172 | 252 | 32% | 5.5 | ||

References

- Göçer, O.; Göçer, K. The Effects of Transportation Modes on Campus Use: A Case Study of a Suburban Campus. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Casas, I.; Sadek, A. Dynamic Demand Estimation and Microscopic Traffic Simulation of a University Campus Transportation Network. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2012, 35, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.; Brown, R. University Campus Transportation Planning. In Proceedings of the Eighth University Planning Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 21–22 September 1978; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/215445216_University_Campus_Transportation_Planning (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Barnes, G.; Davis, G. Understanding Urban Travel Demand. Minneapolis: Center for Transportation Studies; University of Minnesota: Minnesota, MN, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ghodmare, S.; Yadav, G. Transportation Planning Using Conventional Four Stage Modeling. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 2891–2897. [Google Scholar]

- Salisu, U.; Oyesiku, O. Traffic Survey Analysis: Implications for Road Transport Planning in Nigeria. LOGI—Sci. J. Transp. Logist. 2020, 11, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhin, S.; Artemov, A.; Likhachev, D.; Novikov, A.; Starkov, E. Traffic simulation: An analytical review. In Proceedings of the VIII International Scientific Conference Transport of Siberia, Novosibirsk, Russia, 22–27 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Filali, I.; Abdulaal, R.; Melaibari, A. A Novel Green Ocean Strategy for Financial Sustainability (GOSFS) in Higher Education Institutions: King Abdulaziz University as a Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Jamalallail, F. GIS Based Traffic Flow Analysis in King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2019, 12, 688–696. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Sindi, A. Travel Demand Model for Universities—Case Study: King Abdulaziz University. In Proceedings of the International African Conference on Current Studies, Tripoli, Libya, 10–11 February 2023; pp. 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mosaind, M. Traffic Conditions in Emerging University Campuses: King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 7, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindi, A. Conceptual Intelligent Travel Demand Modelling Framework for Universities—Case Study: King Abdulaziz University. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Civil and Environmental Engineering (ICCEE 2022), Online, 6–7 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad, K.; Obaid, L. Tour-based Travel Demand Forecasting Model for a University Campus. Transp. Policy. 2022, 117, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbas, H.; Friedrich, B. Estimating Traffic Demand of Different Transportation Modes using Floating Smartphone Data. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King Abdulaziz University. KAU Traffic Model; King Abdulaziz University: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Atanasova, V.; Angjelevska, B.; Krstanoski, N.; Cvetanovski, I. Calculation of Transport Demand by Applying Software Package PTV Vision VISUM. Int. Sci. J. Mach. Technol. Mater. 2017, 11, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- ITE; Meyer, M. Transportation Planning Handbook, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Incorporated: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Available online: https://content.e-bookshelf.de/media/reading/L-7956797-0086b3b1b0.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- TRB Travel Demand Forecasting: Parameters and Techniques; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/14665/travel-demand-forecasting-parameters-and-techniques (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Tian, Y.; Chiu, Y.; Chai, C. Sunsetting Skim Matrices: A Trajectory-Mining Approach to Derive Travel Time Skim Matrix in Dynamic Traffic Assignment for Activity-Base Model Integration. J. Transp. Land Use 2020, 13, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PTV Group. PTV Visum Manual 2025; PTV Group: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbl, R. A Bio-Physical Model of Trip Generation/Trip Distribution; University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2000; Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/464173/1/755854.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Martinez, O.; Garcia, J.; Kumar, N. The Gravity Model as a Tool for Decision Making. Some Highlights for Indian Roads. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Transport Engineering, Online, 6–8 July 2021; pp. 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Flesser, M. Analysis of Traffic Flows Caused by Kingston Campus, University of Rhode Island. Master’s Thesis, University of Rhode Island, South Kingstown, RI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, G.; Ghodmare, S. Transportation Planning Using Conventional Four Stage Modeling: An Attempt for Identification of Problems in a Transportation System. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, T. A Dynamic Traffic Equilibrium Asignment Paradox. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2000, 34, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimadi, M.; Abbas-Turki, A.; Koukam, A.; Dridi, M.; Mualla, Y. Review of Traffic Assignment and Future Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, K.; Katti, B.; Joshi, G. Literature Review of Traffic Assignment: Static and Dynamic. Int. J. Transp. Eng. 2015, 2, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, D.; Smith, R.; Wunderlich, K. User-Equilibrium Properties of Fixed Points in Dynamic Traffic Assignment. Transp. Res. Part C 1998, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, E.; Oduor, P. Using Multi-Attribute Decision Factors for a Modified All-or-Nothing Traffic Assignment. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrier, H.; Arunakirinathan, V.; Hossain, F.; Habib, M. Developing an Integrated Activity-Based Travel Demand Model for Analyzing the Impact of Electric Vehicles on Traffic Networks and Vehicular Emissions. J. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2679, 1403–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.; Bottom, J.; Mahut, M.; Paz, A.; Balakrishna, R.; Waller, T.; Hicks, J. Dynamic Traffic Assignment: A Primer (Transportation Research Circular); Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Skarphedinsson, A. Evaluating a Simplified Process for Developing a Four-Step Transport Planning Model in VISUM—Application on the Capital Area of Reykjavik; Lunds University: Lund, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, O. The GEH Measure and Quality of the Highway Assignment Models. In Proceedings of the European Transport Conference 2012, Glasgow, UK, 8–10 October 2012; Available online: https://aetransport.org/public/downloads/V7AGa/5664-5218a2370407f.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Oketch, T.; Carrick, M. Calibration and Validation of a Micro-Simulation Model in Network Analysis. In Proceedings of the 84th Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: http://tsh.ca/pdf/TRB05_paper05_1938_final.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Klein, T.; Lowa, S. Applying Measures of Modelling Quality to a National Time Series: A Benchmark for Transport Demand Models. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2019, 42, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillos, B.; Shelton, J.; Chiu, Y. Urban University Campus Transportation and parking planning through a dynamic traffic. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2011, 34, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Types | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Street Network | Primary | 3 lanes |

| Secondary | 2 lanes | |

| Tertiary | 3 lanes | |

| Highway | 4 to 6 lanes | |

| Bus Routes | - | - |

| Gates | Entrances and exits | 7 |

| Parking Areas | Open and Multistoried | 13 |

| Survey Stations | Intermediate links in both directions | 7 |

| Parking Location | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 | P13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | 618 | 516 | 321 | 1167 | 146 | 352 | 968 | 368 | 194 | 422 | 51 | 284 | 358 |

| Gate | G1 | G2 | G2A | G3 | G5 | G7 | PRY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dir. | Ent | Ext | Ent | Ext | Ent | Ext | Ent | Ext | Ent | Ext | Ent | Ext | Ent | Ext |

| Time | 07:15 to 07:30 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 890 | 194 | 496 | 18 | 37 | 3 | 0 | 102 | 294 | 122 | 237 | 564 | 47 | 32 |

| Time | 07:30 to 07:45 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 974 | 388 | 599 | 20 | 64 | 2 | 0 | 117 | 347 | 112 | 342 | 617 | 74 | 49 |

| Time | 07:45 to 08:00 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 1144 | 361 | 475 | 16 | 50 | 2 | 0 | 112 | 374 | 127 | 356 | 725 | 124 | 67 |

| Time | 07:45 to 08:15 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 1228 | 444 | 496 | 14 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 156 | 321 | 147 | 382 | 778 | 144 | 63 |

| Time | 07:15 to 08:15 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 4236 | 1387 | 2066 | 68 | 194 | 8 | 0 | 487 | 1336 | 508 | 1317 | 2684 | 389 | 211 |

| Station | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | |||||||

| Dir. | WB | EB | SB | NB | WB | EB | WB | EB | SB | NB | SB | NB | SB | NB |

| Time | 07:15 to 07:30 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 191 | 646 | 324 | 336 | 429 | 272 | 90 | 368 | 195 | 52 | 116 | 407 | 61 | 40 |

| Time | 07:30 to 07:45 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 381 | 674 | 370 | 623 | 394 | 297 | 94 | 412 | 231 | 64 | 147 | 379 | 67 | 36 |

| Time | 07:45 to 08:00 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 354 | 702 | 355 | 863 | 501 | 321 | 121 | 401 | 213 | 60 | 190 | 295 | 89 | 50 |

| Time | 08:00 to 08:15 | |||||||||||||

| TC | 436 | 787 | 494 | 576 | 465 | 346 | 144 | 385 | 248 | 62 | 159 | 323 | 71 | 46 |

| Time | 07:15 to 08:15 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 1362 | 2809 | 1543 | 2398 | 1789 | 1236 | 449 | 1566 | 887 | 238 | 612 | 1404 | 288 | 172 |

| From | To | Share | Cumulative Share | Number of Trips |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 | 1788 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.365 | 0.555 | 3480 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.2925 | 0.845 | 2789 |

| 1.5 | 2 | 0.1175 | 0.96 | 1120 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 0.03 | 0.9925 | 286 |

| 2.5 | 3 | 0.0075 | 1 | 72 |

| Criteria | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| GEH ≤ 5.0 | Good Match—Indicates an excellent or good match between modelled and observed volumes (within acceptable calibration limits) |

| 5.0 < GEH < 10.0 | Reasonable Match—Indicates a moderate discrepancy. The fit is borderline acceptable and warrants investigation or model adjustment to improve accuracy |

| GEH > 10.0 | Needs Improvement—Indicates a poor match between model and reality indicates significant problem with the model or data that requires corrective action |

| Station | Links | Observed Volume | Modelled Volume | Deviation (%) | GEH Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street Name | Direction | EQL | INC | STO | EQL | INC | STO | EQL | INC | STO | ||

| S1 | Al Ehtifalat Street | EB | 2809 | 2591 | 2593 | 2591 | −8% | −8% | −8% | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| WB | 1362 | 1271 | 1225 | 1238 | −7% | −10% | −9% | 2.5 | 3.8 | 3.4 | ||

| S2 | Ali Al Murtada Street | SB | 1543 | 1812 | 1717 | 1808 | 15% | 10% | 15% | 6.6 | 4.3 | 6.5 |

| NB | 2398 | 2378 | 2301 | 2431 | −1% | −4% | 1% | 0.4 | 2 | 0.7 | ||

| S3 | Al-Malae’b Street | EB | 1789 | 1833 | 2013 | 1853 | 2% | 11% | 3% | 1 | 5.1 | 1.5 |

| WB | 1236 | 1194 | 1203 | 1194 | −3% | −3% | −3% | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.2 | ||

| S4 | EB | 449 | 345 | 521 | 401 | −23% | 14% | −11% | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.3 | |

| WB | 1566 | 1622 | 1648 | 1658 | 3% | 5% | 6% | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.3 | ||

| S5 | Hospital Street | SB | 887 | 769 | 789 | 668 | −13% | −11% | −25% | 4.1 | 3.4 | 7.9 |

| NB | 238 | 293 | 304 | 310 | 19% | 22% | 23% | 3.4 | 4 | 4.3 | ||

| S6 | SB | 612 | 525 | 541 | 534 | −14% | −12% | −13% | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.3 | |

| NB | 1404 | 1581 | 1577 | 1535 | 11% | 11% | 9% | 4.6 | 4.5 | 3.4 | ||

| S7 | Sahha Street | SB | 288 | 361 | 217 | 368 | 20% | −25% | 22% | 4 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

| NB | 172 | 207 | 235 | 197 | 17% | 27% | 13% | 2.5 | 4.4 | 1.8 | ||

| Station | Links | Observed Volume | Modelled Volume | Deviation (%) | GEH Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street Name | Direction | DUE | SDA | SBA | DUE | SDA | SBA | DUE | SDA | SBA | ||

| S1 | Al Ehtifalat Street | EB | 2809 | 2171 | 2601 | 3245 | −23% | −7% | 13% | 12.8 | 4 | 7.9 |

| WB | 1362 | 1084 | 1204 | 1437 | −20% | −12% | 5% | 7.9 | 4.4 | 2 | ||

| S2 | Ali Al Murtada Street | SB | 1543 | 1548 | 1748 | 1641 | 0% | 12% | 6% | 0.1 | 5.1 | 2.5 |

| NB | 2398 | 2085 | 2304 | 2769 | −13% | −4% | 13% | 6.6 | 1.9 | 7.3 | ||

| S3 | Al-Malae’b Street | EB | 1789 | 1621 | 1921 | 1961 | −9% | 7% | 9% | 4.1 | 3.1 | 4 |

| WB | 1236 | 1125 | 1232 | 1431 | −9% | 0% | 14% | 3.2 | 0.1 | 5.4 | ||

| S4 | EB | 449 | 653 | 500 | 539 | 31% | 10% | 17% | 8.7 | 2.3 | 4 | |

| WB | 1566 | 1092 | 1645 | 2063 | −30% | 5% | 24% | 13 | 2 | 11.7 | ||

| S5 | Hospital Street | SB | 887 | 549 | 808 | 865 | −38% | −9% | −2% | 12.6 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| NB | 238 | 548 | 239 | 869 | 57% | 0% | 73% | 15.6 | 0.1 | 26.8 | ||

| S6 | SB | 612 | 535 | 561 | 625 | −13% | −8% | 2% | 3.2 | 2.1 | 0.5 | |

| NB | 1404 | 1537 | 1596 | 2180 | 9% | 12% | 36% | 3.5 | 5 | 18.3 | ||

| S7 | Sahha Street | SB | 288 | 320 | 248 | 278 | 10% | −14% | −3% | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| NB | 172 | 180 | 205 | 215 | 4% | 16% | 20% | 0.6 | 2.4 | 3.1 | ||

| Station | Links | Observed Volume | Modelled Volume | Deviation (%) | GEH Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street Name | Direction | |||||

| S1 | Al Ehtifalat Street | EB | 4 | 5 | 20% | 0.5 |

| WB | 2 | 2 | 0% | 0 | ||

| S2 | Ali Al Murtada Street | SB | 3 | 3 | 0% | 0 |

| NB | 5 | 5 | 0% | 0 | ||

| S3 | Al-Malae’b Street | EB | 5 | 6 | 17% | 0.4 |

| WB | 6 | 7 | 14% | 0.4 | ||

| S4 | EB | 6 | 6 | 0% | 0 | |

| WB | 5 | 5 | 0% | 0 | ||

| S5 | Hospital Street | SB | 4 | 4 | 0% | 0 |

| NB | 2 | 3 | 33% | 0.6 | ||

| S6 | SB | 2 | 2 | 0% | 0 | |

| NB | 2 | 2 | 0% | 0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azmain, M.; Tiwari, A.; Abdulaal, J.A.E.; Gbban, A.M. Developing a Simulation-Based Traffic Model for King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410985

Azmain M, Tiwari A, Abdulaal JAE, Gbban AM. Developing a Simulation-Based Traffic Model for King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410985

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzmain, Mohaimin, Alok Tiwari, Jamal Abdulmohsen Eid Abdulaal, and Abdulrhman M. Gbban. 2025. "Developing a Simulation-Based Traffic Model for King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410985

APA StyleAzmain, M., Tiwari, A., Abdulaal, J. A. E., & Gbban, A. M. (2025). Developing a Simulation-Based Traffic Model for King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 17(24), 10985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410985