Research on Effect of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emission Reduction-Based on the Moderating Effect of Institutional Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mechanisms of the Digital Economy’s Impact on Agricultural Carbon Emissions

2.2. Impact of Institutional Arrangements on Agricultural Carbon Emissions

2.3. Critical Analysis

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Institutional Context

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.2.1. Mechanisms by Which the Digital Economy Improves Agricultural Carbon Emissions

3.2.2. Direct and Indirect Effects of Institutional Quality Improvement on Agricultural Carbon Emissions

3.2.3. The Regulatory Effect of Institutional Quality on Agricultural Carbon Emissions

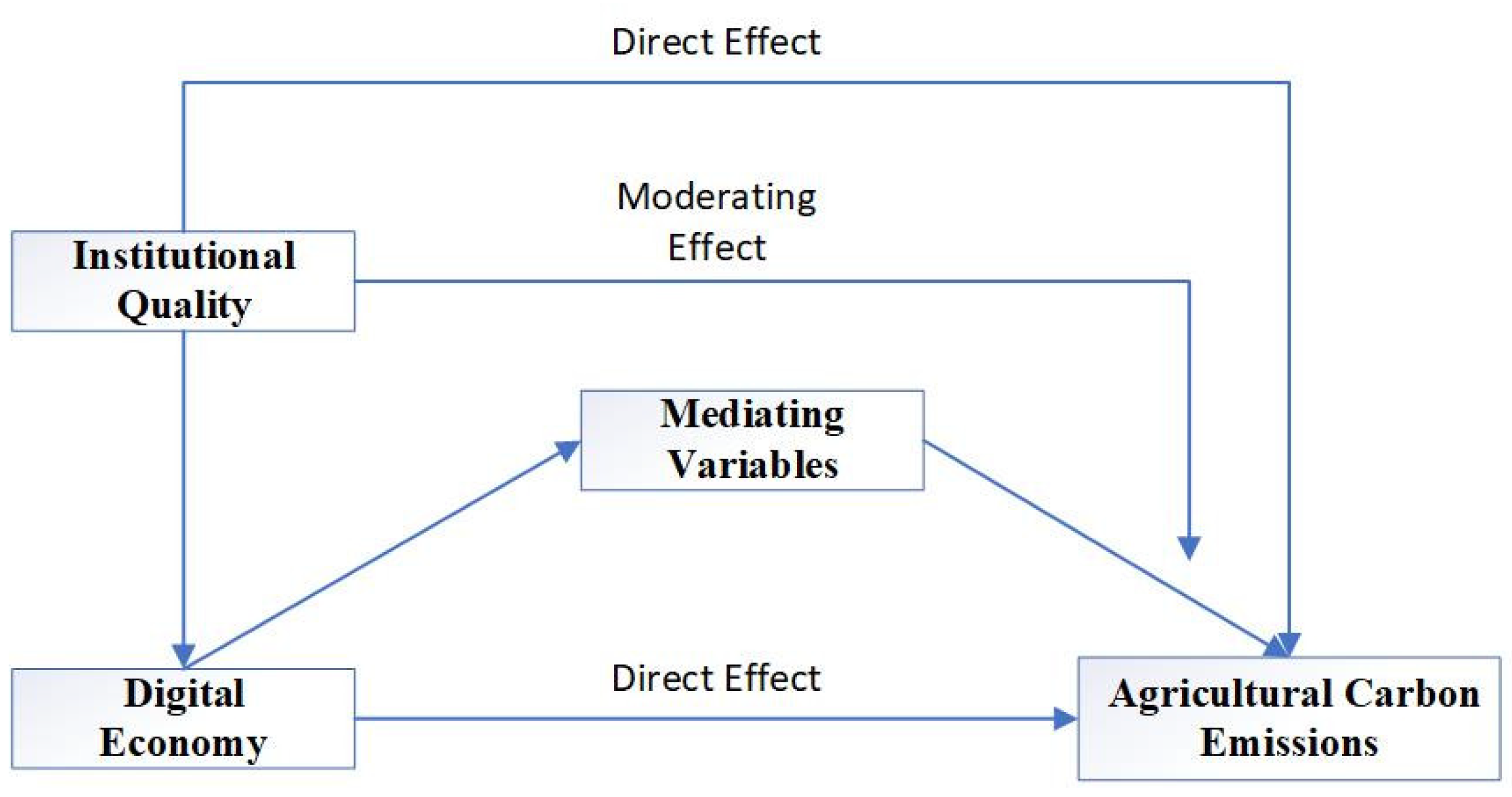

3.3. Model Diagram

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample Selection

4.2. Model Specification and Variable Definition

4.2.1. Model Specification

4.2.2. Variable Definitions

4.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

5. Empirical Research

5.1. The Basic Empirical Model Results

5.2. Mechanism Analysis

5.2.1. Role of the Digital Economy

5.2.2. The Role of Institutional Quality

5.2.3. The Moderating Role of Institutional Quality

5.3. Robustness Test Analysis

5.3.1. Dynamic Panel Model

5.3.2. Incorporating Province-Time Fixed Effects

5.3.3. Random 50% Sampling

5.3.4. Adjusting the Time Window

5.3.5. Truncating the 5th Percentile

6. Further Discussion: The Nonlinear Impact of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emissions

6.1. The Test of Direct Impact Concerning Digital Economy

6.2. Testing the Mediating Effect of Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emissions

6.3. Testing the Intermediary Effect on the Digital Economy

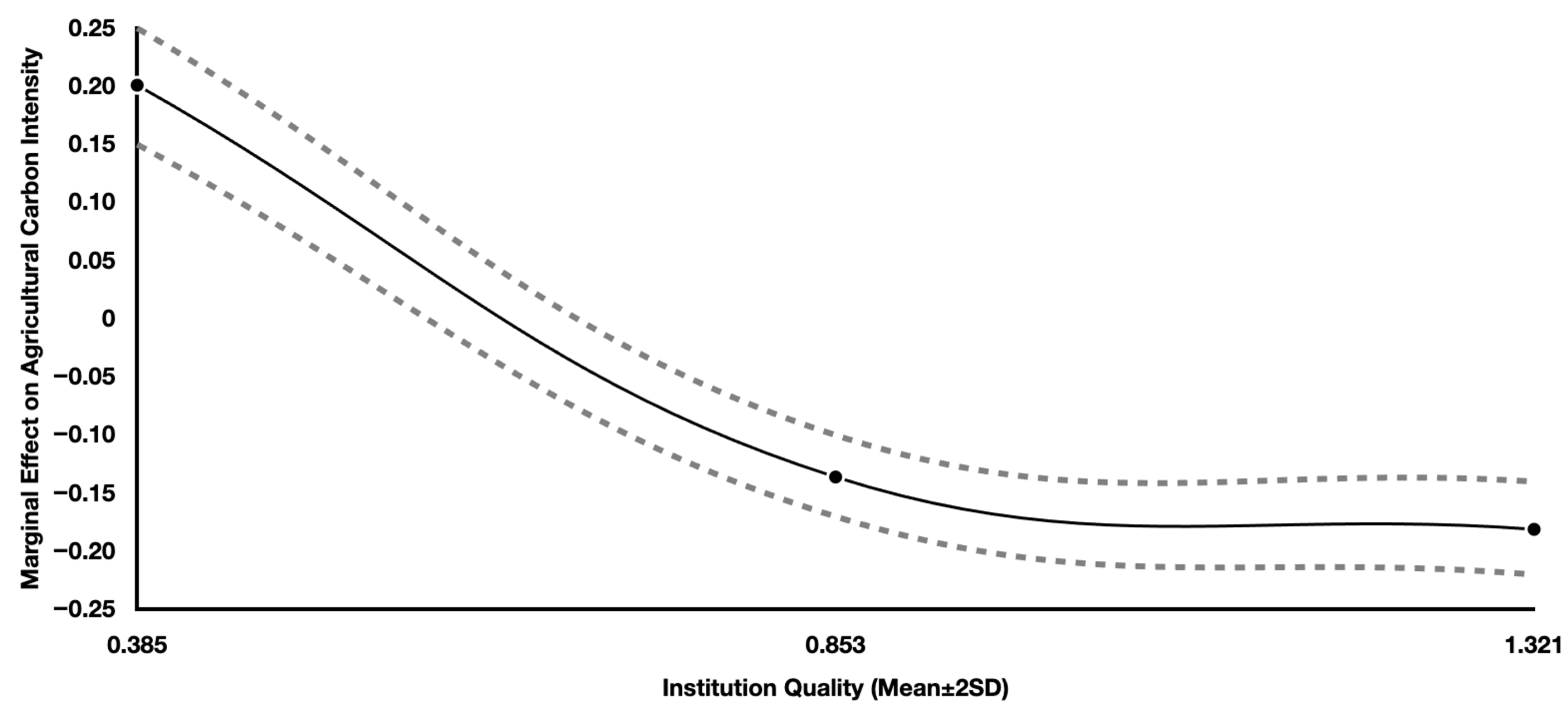

6.4. Testing the Moderating Effect of Institutional Quality

7. Conclusions and Shortage

7.1. Research Conclusions

7.2. Policy Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Dynamic Panel (1) | Province-Time Variable (2) | Random 50% (3) | Adjust Time (4) | Shrinkage (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon emission intensity | −0.064 *** | ||||

| First-order lag | |||||

| (0.021) | |||||

| Digital Economy | −0.299 ** | −0.340 ** | −0.348 ** | −0.375 ** | −0.406 *** |

| (0.137) | (0.138) | (0.141) | (0.146) | (0.139) | |

| Institutional Quality | −0.179 ** | −0.199 ** | −0.188 *** | −0.202 *** | −0.214 *** |

| (0.076) | (0.096) | (0.065) | (0.069) | (0.055) | |

| Digital Economy × Institutional Quality | −0.059 ** | −0.046 *** | −0.061 ** | −0.073 ** | −0.088 *** |

| (0.023) | (0.016) | (0.027) | (0.031) | (0.021) | |

| Constant | 2.985 *** | 1.874 * | 3.654 * | 3.984 | 4.033 |

| (0.867) | (1.106) | (2.156) | (3.511) | (3.621) | |

| Control Variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual Effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time Effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Endogeneity test F value | 15.334 | 22.364 | - | - | 34.845 |

| Weak instrumental variable test F value | 28.765 | 26.432 | - | - | 16.872 |

Appendix B

| Test | Value | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) Test | 0.892 | - | - |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | 18,247.33 | 66 | 0.000 |

| Component | Eigenvalue | Proportion of Variance Explained | Cumulative Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 7.952 | 88.40% | 88.40% |

| Factor 2 | 0.613 | 6.80% | 95.20% |

| Factor 3 | 0.287 | 3.20% | 98.40% |

| Factor 4 | 0.098 | 1.10% | 99.50% |

| Other | <0.05 | <0.6% each | 100.00% |

References

- Yu, W. Spatial spillover effects and heterogeneity analysis of digital economy on regional carbon emission reduction performance. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2024, 43, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Ren, Y.; Chai, Z. Digital infrastructure construction and urban carbon emissions under the “dual carbon” goals: A quasi-natural experiment based on the “Broadband China” pilot policy. China’s Econ. Probl. 2023, 5, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Guo, J. Digital economy empowers the carbon emission reduction effect of green agricultural development. J. Jiangxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 3, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Xv, J. Intermediate goods trade liberalization, institutional environment, and productivity evolution. World Econ. 2015, 38, 80–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Song, Y.; Lin, X.; Fu, C. Discussion on Several Issues in China’s Digital Village Construction. China’s Rural. Econ. 2021, 4, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wu, Y. Digital economy development, digital divide and income gap between urban and rural residents. South. Econ. 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, Y. Digital Economy Theoretical System and Research Outlook. Manag. World 2022, 38, 208–224+213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Zhang, X. Digital economy, non-agricultural employment and social division of labor. Manag. World 2022, 38, 72–84+311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Chen, Y. The integrated development of digital economy and agricultural and rural economy: Practical models, practical obstacles and breakthrough paths. Agric. Econ. Issues 2020, 7, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, J. Research on digital new productivity and high-quality development of my country’s agriculture. J. Shaanxi Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 52, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.A. Big data insights into pest spread. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 955–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Alam, P.; Kumar, P.; Kaur, S. Internet of things for precision agriculture applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 Fifth International Conference on Image Information Processing (ICIIP), Shimla, India, 15–17 November 2019; pp. 420–424. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wei, W. The Impact of Rural Digital Economy Development on Agricultural Carbon Emissions: A Panel Data Analysis Based on 29 Provinces. J. Jiangsu Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 25, 20–32+47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, S. Research on the impact of digital economy development on China’s agricultural carbon emissions. China’s Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2025, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. The impact and mechanism of digital rural development on agricultural carbon emission intensity. Stat. Decis. Mak. 2023, 39, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hong, C. Digital inclusive finance and green and low-carbon development of agriculture: Level measurement and mechanism testing. Financ. Theory Pract. 2023, 1, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Wang, B.; Lu, M.; Irfan, M.; Miao, X.; Luo, S.; Hao, Y. The strategy to achieve zero-carbon in agricultural sector: Does digitalization matter under the background of COP26 targets? Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 106916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, J.; Pata, U.K.; Li, R.; Kartal, M.T. Digital economy and carbon dioxide emissions: Examining the role of threshold variables. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Darabidarabkhani, Y.; Shah, A.; Memon, J. Evaluating power efficient algorithms for efficiency and carbon emissions in cloud data centers: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, R.; Roy, S.; Mondal, H.; Chowdhury, D.R.; Chakraborty, S. Energy-efficient approach to lower the carbon emissions of data centers. Computing 2021, 103, 1703–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhanag, Y. Mechanism and Empirical Study on the Impact of Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emissions. J. South-Cent. Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 44, 139–148+187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Chi, J.; Wang, Y. Study on the spatial spillover and threshold effect of rural digitalization on agricultural carbon emission intensity. J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 49, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W. The impact mechanism of rural digital economy on agricultural carbon emissions: An empirical study on the mediating effect of rural industrial integration development. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 18, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.H.; Geng, F.Y.; Zhang, H.S. Research on the impact of digital economic development on carbon emission efficiency of planting industry: Empirical test based on mediation and threshold effects. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. (Chin. Engl.) 2024, 32, 919–931. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Ji, X.; Cheng, C.; Liao, S.; Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y. Digital economy empowers sustainable agriculture: Implications for farmers’ adoption of ecological agricultural technologies. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tan, C. The impact of digital economic development on agricultural carbon emissions and its temporal and spatial effects. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2023, 43, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Liao, H. Research on the impact and mechanism of digital economy on agricultural carbon emissions. Reform 2024, 9, 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, J.; Sow, Y.; Cui, X.; Chen, H.; Shen, Q. The impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions from cultivated land use. Land 2023, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; He, Q.; Qi, Y. Digital economy, agricultural technological progress, and agricultural carbon intensity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Wang, L. Spatial effects and mechanisms of digital inclusive finance’s impact on China’s agricultural carbon emission intensity. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 593–608. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Song, J.; Ma, W. Impact path of digital economy on carbon emission efficiency: Mediating effect based on technological innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; You, Y. The Impact of the Rural Digital Economy on Agricultural Green Development and Its Mechanism: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M. Study on the Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Low-Carbon Agricultural Development in Guizhou Province—Empirical analysis based on two-way fixed effects model and mediated effects model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 242, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D. The Impact of the Digital Economy on Energy Utilization Efficiency in Chinese Cities: A Perspective Based on Technological Empowerment and Spillover Effects. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Chang, C.; Zhang, Y. The impact of the development of digital economy industry in the Yangtze River Economic Belt on innovation efficiency—Based on the perspective of technological diversification and technological spillover. Econ. Syst. Reform 2024, 2, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Gong, Q. Development strategy and economic system selection. Manag. World 2010, 3, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Lu, W. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Advantages of High-Tech Industrial Agglomeration—Based on Empirical Data from 30 Provinces and Cities in China. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2017, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Gao, N.; Wei, W. Research on the impact of new energy industry agglomeration on economic growth. J. Xihua Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2016, 35, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.A. A reconsideration of agricultural law: A call for the law of food, farming, and sustainability. William Mary Environ. Law Policy Rev. 2009, 34, 935. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, D.E.; Barton, J.H. Environmental regulation for agriculture: Towards a framework to promote sustainable intensive agriculture. Stanf. Environ. Law J. 2002, 21, 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.D.; Rishi, M.; Bae, J.H. Green official development Aid and carbon emissions: Do institutions matter? Environ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 26, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Research on Digital Economy Empowering Urban-Rural Integration Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Tui, Z.; Ma, C. Digital Economic Development and Rural Revitalization: From the Perspective of Factor Flow and Absorption Capacity. Bus. Econ. Res. 2024, 14, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Fan, Z.; Yu, S. Digital Economy and Agricultural and Rural Modernization: A Study Based on the Prefectural-Level City Level. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2024, 4, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, R.; Kapelianis, D.; Montoya, M.-J.R.; Vora, G. The creative economy, innovation and entrepreneurship: An empirical examination. Creat. Ind. J. 2021, 14, 23–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, T.; Li, Z. Digital inclusive finance, economic growth and innovative development. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 3064–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wan, G.; Zhang, J.; He, Z. Digital economy, financial inclusion and inclusive growth. China Econ. 2020, 15, 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, J. Synergies of technological and institutional innovation driving manufacturing transformation: Insights from northeast China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 1014–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottemann, J.E. Technological-Institutional Synergy and the Extent of National E-Governments. Int. J. Public Adm. 2011, 34, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dhaliwal, J. An investigation of resource-based and institutional theoretic factors in technology adoption for operations and supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 120, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J.; Barley, S.R. Technology and institutions: What can research on information technology and research on organizations learn from each other? MIS Q. 2001, 25, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, F.; Seamans, R.; Tadelis, S. Transaction cost economics in the digital economy: A research agenda. Strateg. Organ. 2025, 23, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofin, O.P. Digital economy, institutional quality and economic growth in selected countries. Central Bank Niger. J. Appl. Stat. 2023, 14, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Ren, Y. Digital Economy Development, Institutional Quality and Upstreamness of Global Value Chains. Front. Econ. China 2022, 17, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M.; Dyson, A.; Goldrick, S.; West, M. Developing Equitable Education Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Annual report 2000: Marketization index for China’s provinces. China World Econ. 2001, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Panchasara, H.; Samrat, N.H.; Islam, N. Greenhouse gas emissions trends and mitigation measures in Australian agriculture sector—A review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Feng, X. Research on the Design of a Digital Economy Indicator System for Rural Areas from the Perspective of Digital Village Construction. Agric. Mod. Res. 2020, 41, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.L.; Zhu, H.P. China Marketization Index—2011 Report on the Relative Progress of Marketization in Various Regions; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, N.; Katz, J.N. What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1995, 89, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bover, O. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S.; Windmeijer, F. Estimation in dynamic panel data models: Improving on the performance of the standard GMM estimator. In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels; Elsevier Science: Kidlington, UK, 2001; pp. 53–91. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Li, Y. Government fiscal decentralization and haze and carbon reduction: Evidence from the fiscal Province-Managing-County reform. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 119020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Definition | Sign | Note. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained Variable | Carbon Emission Intensity | Total carbon emissions divided by total agricultural output value | |

| Explanatory Variable | Digital Economy | Regional digital economy development level, obtained by reducing the dimensionality of a series of indicators. | |

| Institutional Quality | Referencing the marketization index published by Fan Gang et al. (2011), the same indicators were used to calculate the data [58]. | ||

| Mediating Variable | Years of Education Per Capita | Average years of education per farmer. Data for some prefectures and cities is unavailable, so provincial data is used instead. | |

| Agricultural Loans Per Capita | Total agricultural loans/rural population | ||

| Average Total Power of Agricultural Machinery | Total agricultural machinery power divided by total agricultural output value | ||

| Control Variable | Per Capita Income of Farmers | Per capita income of farmers | |

| Financial Support for Agriculture | Total agricultural, forestry and water expenditure |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicators | Measuring Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Infrastructure | Internet penetration rate | Number of Internet Access Users |

| Mobile phone ownership | Number of Mobile Phone Users | |

| Rural radio and television coverage | Percentage of Population with Access to Radio and Television | |

| Digital Industry | Information Industry | Number of Employees in Information Transmission, Computer Services, and Software |

| Telecommunications industry | Total Telecommunications Business Volume | |

| Digital Innovation | New technology R&D capability | Number of Intellectual Property Applications |

| R&D investment | Expenditure on Science and Technology | |

| Digital Financial Inclusion | Digital finance coverage breadth | Digital Inclusive Finance Coverage Index |

| Digital finance usage depth | Digital Inclusive Finance Penetration Index | |

| Digitalization level | Digital Inclusive Finance Digitalization Level |

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Std | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Emission Intensity | 6048 | 1.813 | 0.987 | 0.136 | 7.789 |

| Digital Economy | 6048 | 5.629 | 1.369 | 1.433 | 10.369 |

| Institutional Quality | 6048 | 0.853 | 0.234 | 0.126 | 2.331 |

| Average Years of Education per Capita | 6048 | 6.663 | 1.069 | 3.211 | 12.69 |

| Average Agricultural Loan Amount per Farmer | 6048 | 7.621 | 1.986 | 0.553 | 15.698 |

| Average Agricultural Total Power | 6048 | 1.987 | 0.369 | 0.201 | 4.965 |

| Average Income Level per Farmer | 6048 | 8566.123 | 2136.781 | 1569.32 | 18,954.36 |

| Fiscal Support for Agriculture | 6048 | 6123.669 | 1875.691 | 369.233 | 14,256.98 |

| Variables | FE (1) | PCSE (2) | FE (3) | PCSE (4) | FE (5) | PCSE (4) | FE (7) | PCSE (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Economy | −0.385 *** | −0.365 *** | −0.323 *** | −0.336 *** | −0.357 *** | −0.396 *** | ||

| (0.081) | (0.126) | (0.116) | (0.124) | (0.121) | (0.133) | |||

| Institutional Quality | −0.155 ** | −0.183 ** | −0.179 ** | −0.183 * | −0.195 ** | −0.201 ** | ||

| (0.074) | (0.089) | (0.091) | (0.109) | (0.097) | (0.101) | |||

| Digital Economy × Institutional Quality | −0.043 ** | −0.068 ** | ||||||

| (0.021) | (0.030) | |||||||

| Constant | 2.541 * | −2.227 ** | 1.323 | 2.361 * | 2.087 * | −1.851 ** | 1.794 ** | 2.169 * |

| (1.365) | (1.087) | (1.021) | (1.333) | (1.087) | (0.774) | (0.811) | (1.185) | |

| Control Variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual Effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time Effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Obs | 6048 | 6048 | 6048 | 6048 | 6048 | 6048 | 6048 | 6048 |

| R2 | 0.612 | 0.597 | 0.609 | 0.613 | 0.701 | 0.655 | 0.634 | 0.695 |

| Variables | IV REG (1) | Province-Time Variable (2) | Winsorize (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Economy | −0.202 *** | −0.198 *** | −0.185 *** |

| (0.055) | (0.065) | (0.036) | |

| Institutional Quality | −0.152 *** | −0.163 *** | −0.155 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.054) | (0.017) | |

| Digital Economy × Institutional Quality | −0.069 ** | −0.081 ** | −0.097 *** |

| (0.033) | (0.0413) | (0.026) | |

| Constant | 1.845 ** | 2.361 ** | 3.339 * |

| (0.851) | (0.949) | (2.013) | |

| Control Variables | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual Effect | Control | Control | Control |

| Time Effect | Control | Control | Control |

| Endogeneity test F value | 15.698 | 22.694 | 36.325 |

| Weak instrumental variable test F value | 32.688 | 17.698 | 19.846 |

| Explanatory Variable | Mediating Variable | Functional Decomposition | Observation Coefficient | Bootstrap Std | Z Value | p Value | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Up | |||||||

| Digital Economy | Average years of Education per capita | Direct Effect | −0.257 | 0.032 | −8.006 | 0.000 | −0.320 | −0.194 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.136 | 0.101 | −1.347 | 0.362 | −0.334 | 0.062 | ||

| Agricultural loans per capita | Direct Effect | −0.186 | 0.069 | −2.715 | 0.000 | −0.320 | −0.052 | |

| Indirect Effect | −0.277 | 0.122 | −2.270 | 0.000 | −0.516 | −0.038 | ||

| Average Agricultural Total Mechanical Power | Direct Effect | −0.192 | 0.071 | −2.704 | 0.000 | −0.331 | −0.053 | |

| Indirect Effect | −0.223 | 0.098 | −2.276 | 0.000 | −0.415 | −0.031 | ||

| Explanatory Variable | Functional Decomposition | Coefficient | Bootstrap Std | Z Value | p-Value | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Up | ||||||

| Institutional Quality | Total Effect | −0.179 | 0.029 | −6.172 | 0.000 | −0.236 | −0.122 |

| Direct Effect | −0.146 | 0.047 | −3.106 | 0.000 | −0.238 | −0.054 | |

| Explanatory Variable | Computing Node | Computing Value | Coefficient | Bootstrap Std | Z-Value | p-Value | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Up | |||||||

| Institutional Quality | mean − 2 × sd | 0.385 | 0.201 | 0.034 | 5.924 | 0.000 | 0.135 | 0.268 |

| mean | 0.853 | −0.136 | 0.016 | −8.500 | 0.000 | −0.167 | −0.105 | |

| Mean + 2 × sd | 1.321 | −0.181 | 0.029 | −6.241 | 0.000 | −0.238 | −0.124 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Guan, B. Research on Effect of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emission Reduction-Based on the Moderating Effect of Institutional Quality. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410984

Wang Z, Guan B. Research on Effect of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emission Reduction-Based on the Moderating Effect of Institutional Quality. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410984

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhaoyang, and Bin Guan. 2025. "Research on Effect of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emission Reduction-Based on the Moderating Effect of Institutional Quality" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410984

APA StyleWang, Z., & Guan, B. (2025). Research on Effect of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Carbon Emission Reduction-Based on the Moderating Effect of Institutional Quality. Sustainability, 17(24), 10984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410984