A Multi-Layered Framework for Circular Modular Timber Construction: Case Studies on Module Design and Reuse

Abstract

1. Introduction

- “What principles and design logics inform timber modularity across different scales, from discrete components to integrated units?”;

- “How do structural characteristics influence system selection in modular timber construction?”;

- “How do prefabrication levels and integrated modular units support efficient timber construction?”;

- “How can modular components be designed for reuse to enhance adaptability in construction?”

- “To identify the underlying design logics and modular principles that govern the generation of timber modules at different scales.”;

- “To determine how structural conditions influence the selection and configuration of modular systems.”;

- “To clarify how prefabrication levels and integrated modular units relate to systemization and construction efficiency.”;

- “To explore reuse-oriented design factors that influence the adaptability of modular systems.”

2. Methods

2.1. Case Selection Criteria

2.2. Case Studies Overview

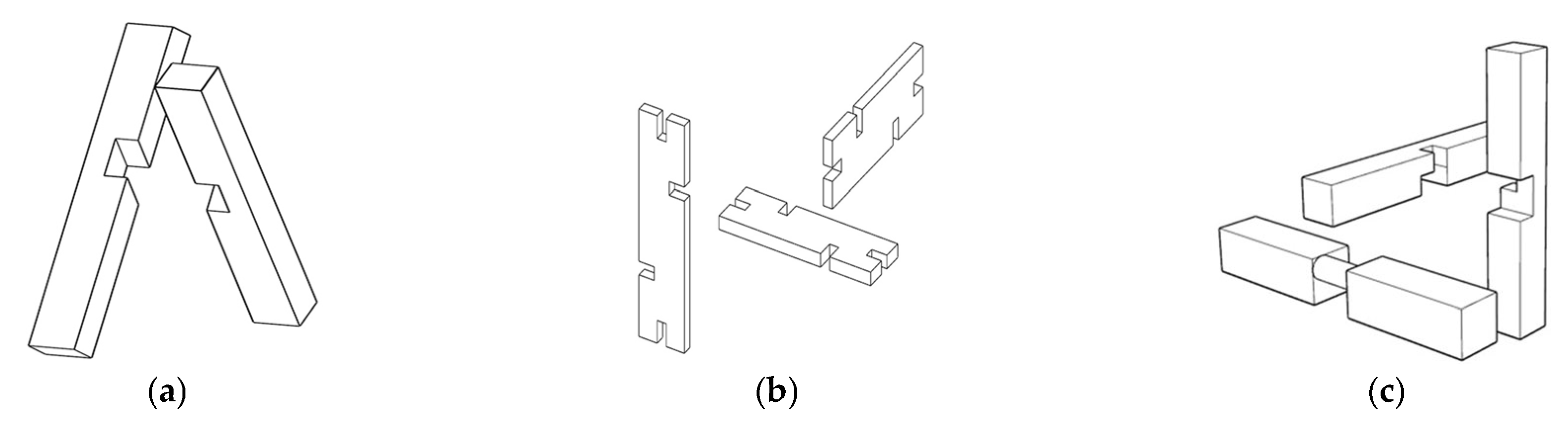

- (a)

- SunnyHills utilizes a modular approach in which individual timber components are assembled to form a cohesive structure and create a unique esthetic architectural form. The structure is primarily composed of linear timber elements, which are repeatable, resulting in a modular construction process. Based on the decision to design at a small scale to create a forest-like environment within the city, timber with a cross-section of 6 cm by 6 cm is joined using the traditional jigoku-gumi technique [37], enabling the construction of a three-story building without requiring large columns. The modularity in this case expresses the precision of manufacturing, and the joint connections resemble a type of mortise-and-tenon.

- (b)

- Cidori, meaning “one thousand birds [38],” is composed of numerous slender wooden elements vertically interwoven to form an inverted nest-like framework. The pieces are precisely notched to interlock with one an-other, Stability is achieved through the combination of compressive forces and friction generated at the carefully crafted joints.

- (c)

- Kodama employs a connection system based on vertical slot joints, whereby six identical notched wooden components interlock through precisely aligned grooves to form a basic unit [39]. This jointing method not only ensures structural stability without the need for additional fasteners, but also creates a distinctive esthetic language. The intermeshing slots allow the structure to grow into irregular and non-repetitive patterns, supporting architectural diversity while reflecting the craftsmanship and artistry of the construction process.

- (d)

- Nine Bridges Golf Resort integrates small-scale components modules into architectural design, with an emphasis on curved elements. The tree-shaped structural units consist of slender timber columns that bundle together in a ring configuration to support the roof [40]. The ends of these columns gradually curve and spread out near the roof plane. The pattern adapts to the shape of the canopy, undergoing a form transformation to align with its organic structure. These components are further broken down into modular sub-units to enable mass production and assembly.

- (e)

- Nest We Grow was realized as a design-build project responding to a competition that promoted the use of renewable materials. The structural system relies on assembling small timber components into larger composite columns, thereby enlarging the cross-section, and enhancing load-bearing capacity [41]. These columns are integrated with horizontal members to form a timber frame structure, in which metal connectors are incorporated at the joints to improve stability and ensure structural reliability. The resulting open framework not only provides support but also defines spaces for food storage and communal activities, exemplifying a timber construction approach that combines structural strength, spatial versatility, and the principles of sustainable practice.

- (f)

- In addition to linear elements, panelized components are commonly used as modular units for quickly building the envelope. A typical example is Jyubako [42], a trailer house whose exterior consists of different combinations of prefabricated panels. This panel-based strategy highlights mobility, speed, and ease of assembly, allowing the structure to be built in a short period. The case illustrates how panelized modular construction supports a lightweight, temporary system while retaining flexibility in spatial arrangement.

- (g)

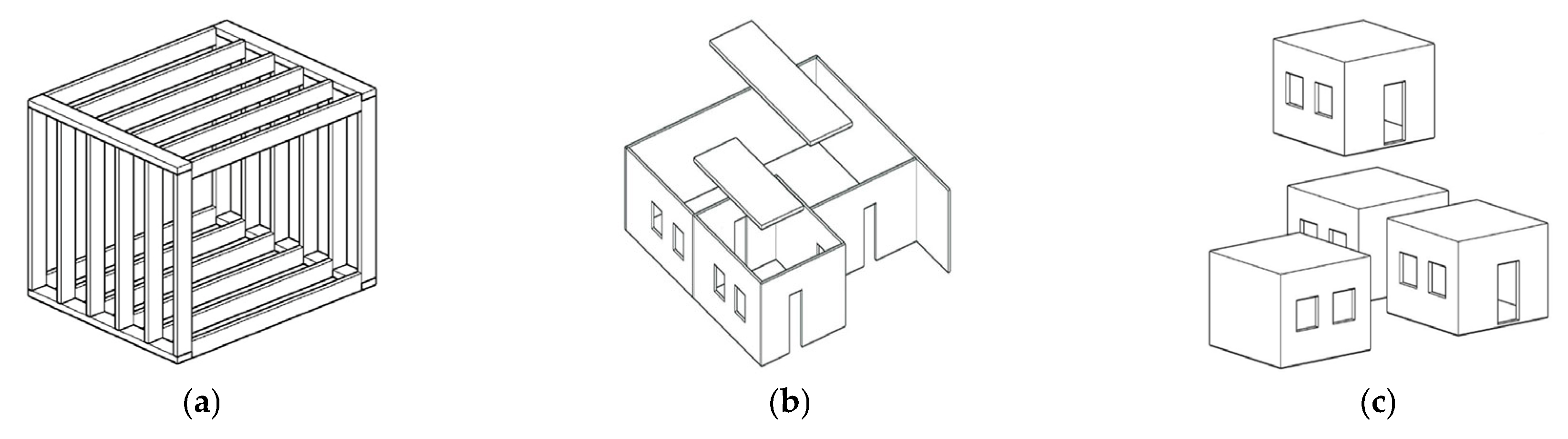

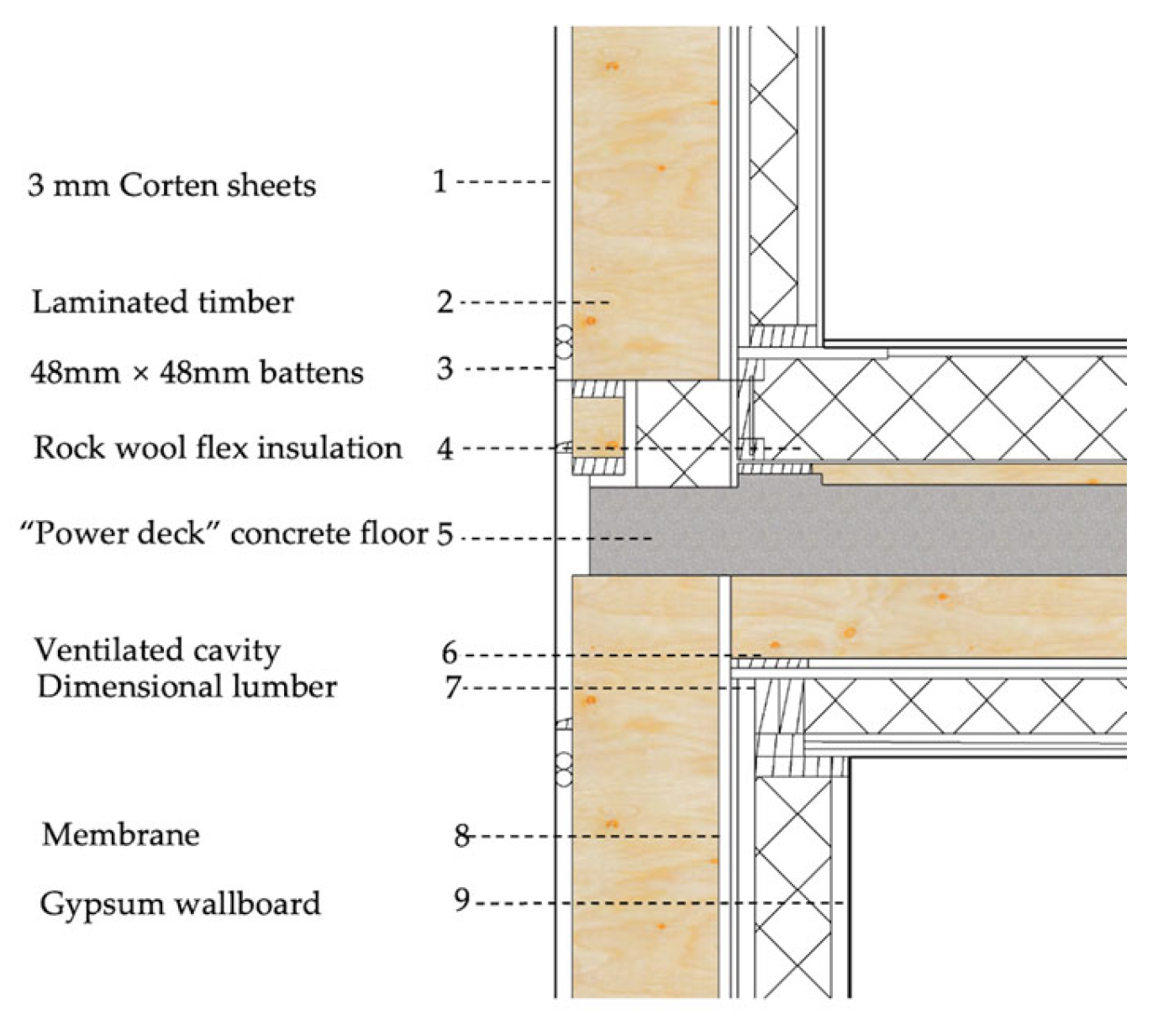

- Treet uses a combination of room modules and a structural framework, starting with four modules stacked vertically on a concrete foundation. The fifth-floor functions as a power deck, with smaller modules inserted. The composition of modules is formed in a stacked manner, displaying an ordered arrangement, with a glulam frame built around them to resist horizontal and vertical forces [43]. The entire building was completed by alternating between the load-bearing frame and the box modules. These room modules primarily serve to amplify functionality and are manufactured as integrated units in a factory. The prefabricated modules are then assembled on-site, improving construction speed and efficiency.

- (h)

- The Modular School provides flexible, temporary educational spaces through a prefabricated timber system. Two classrooms per floor are linked by a central corridor, forming a structure of up to three stories. Prefabricated façades, acoustic ceilings, and plasterboard-clad timber frames enhance comfort and construction efficiency, while individual foundations and large, square modules allow rapid on-site assembly [9].

- (i)

- Woodie Student Hostel comprises 371 prefabricated timber room modules measuring approximately 6.30 m by 3.30 m arranged in a comb-like structure with E-shaped floor plans. The production line manufactured four modules per day, with modules transported from Austria and delivered on demand to the site. Installation progressed at a rate of up to twelve modules per day, and the modular timber façade was added after module assembly. The entire on-site construction was completed within ten months, with timber structures dimensioned for fire resistance [9].

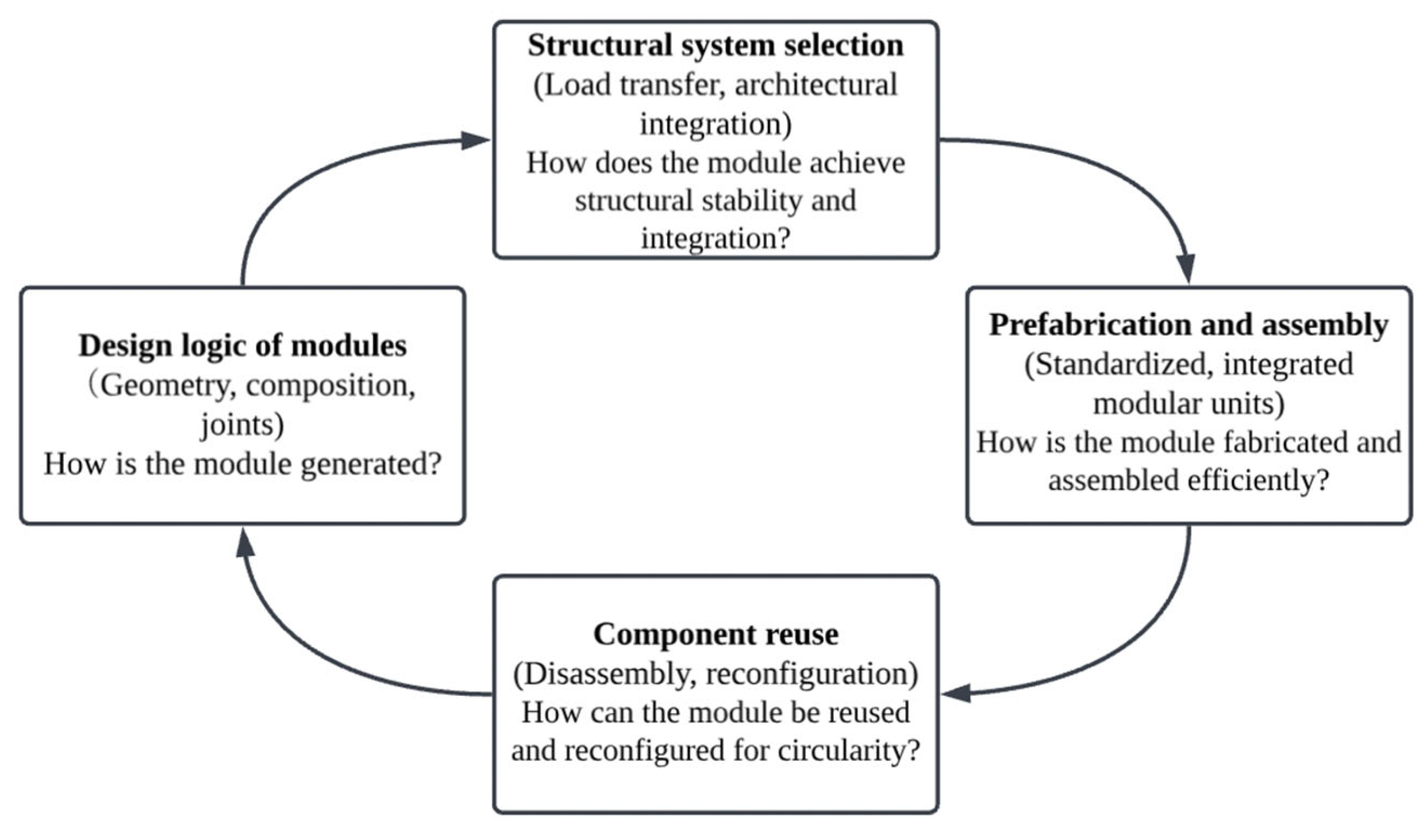

2.3. Analytical Framework

- (a)

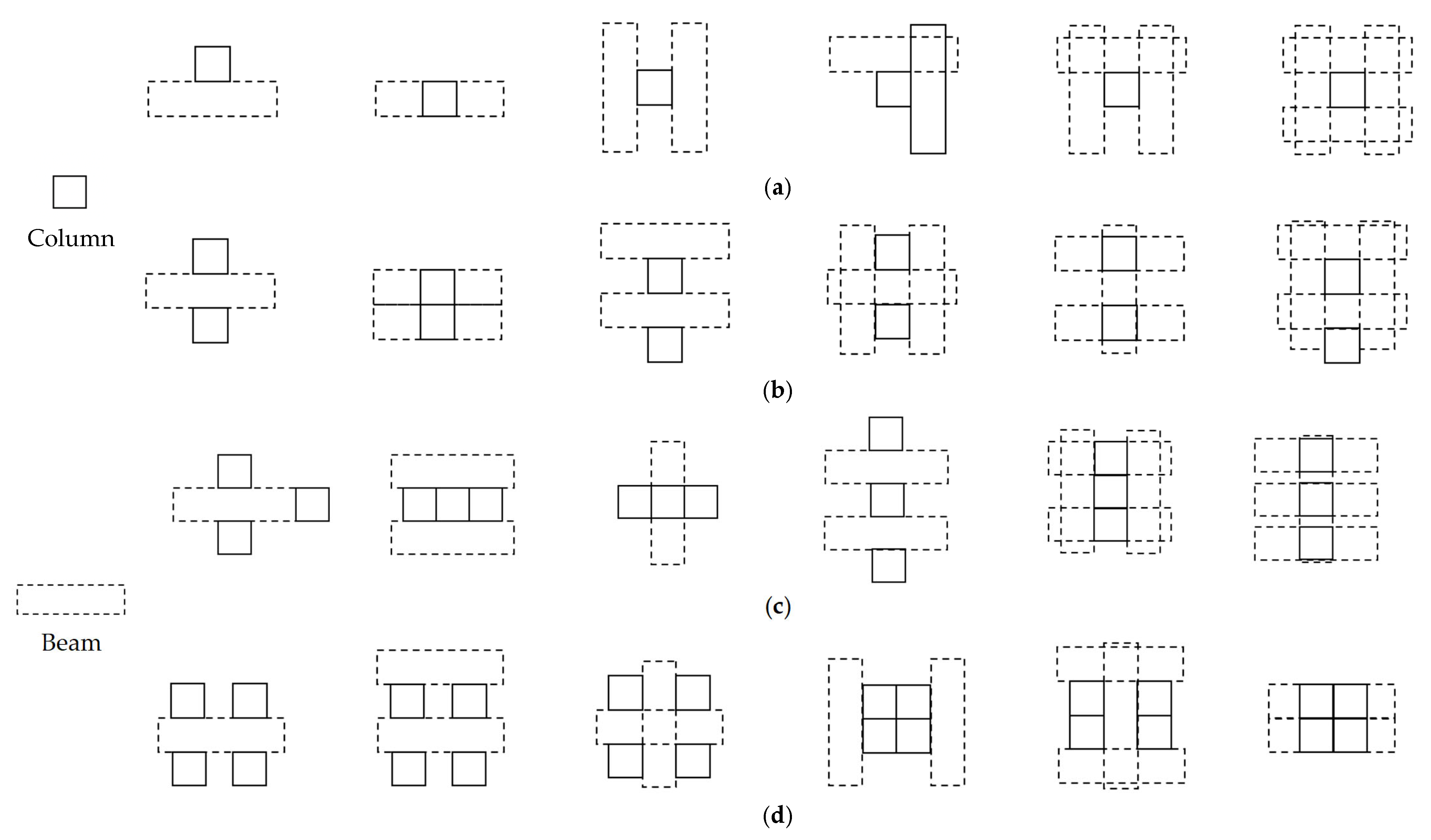

- Design logic of modulesThis dimension examines modules of different scales from distinct design perspectives, emphasizing dimensional and formal characteristics, considering geometric configuration, component articulation, and connection logic. It investigates how variations in geometry, proportion, and composition contribute to spatial adaptability, flexibility, and modular arrangement.

- (b)

- Structure system selectionThe structural system is a primary determinant of modular organization and architectural expression. This dimension analyzes how different structural configurations influence stability, integration, and adaptability through system typologies, load transfer mechanisms, and the correspondence between structural logic and spatial configuration.

- (c)

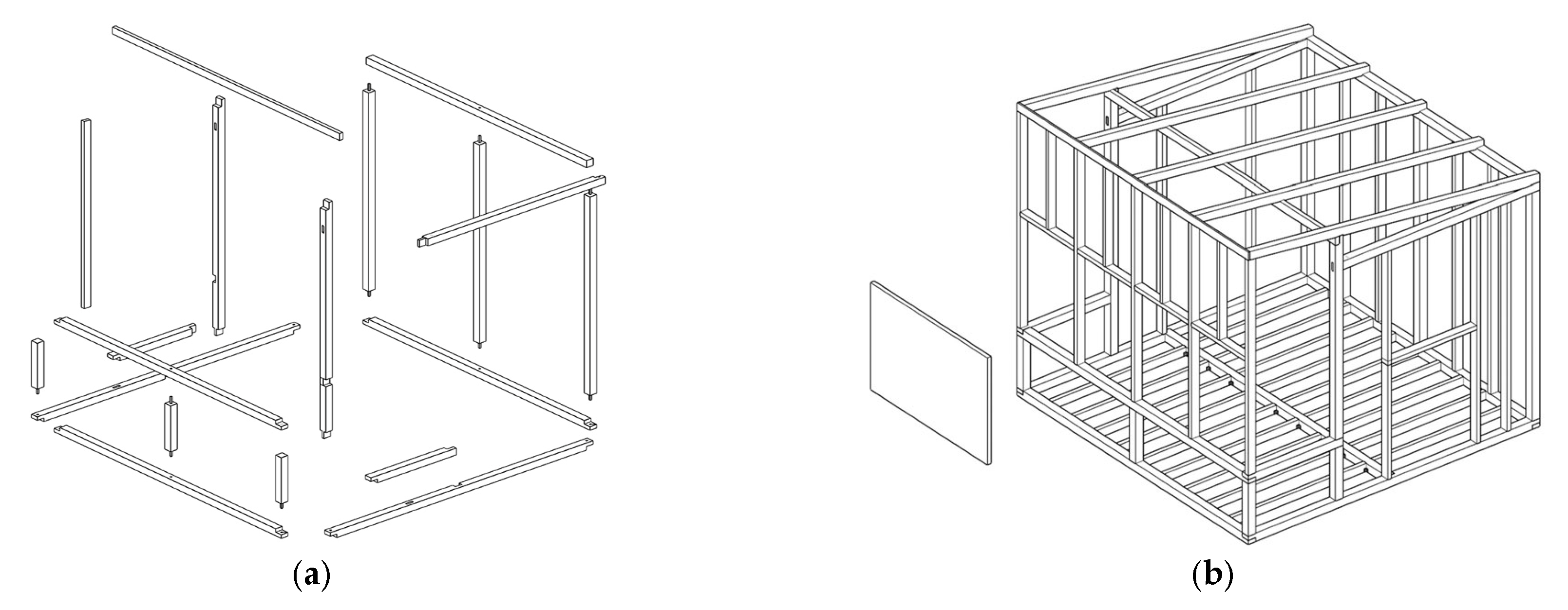

- Prefabrication and assembly efficiencyA systematic exploration of modular construction principles discusses the integration of modular logic into timber construction through standardized units and layered structures. Components are analyzed across levels of prefabrication, and an integrated wall unit representing the consolidation of materials and functional performance is considered in terms of constructability, functional performance, and assembly sustainability.

- (d)

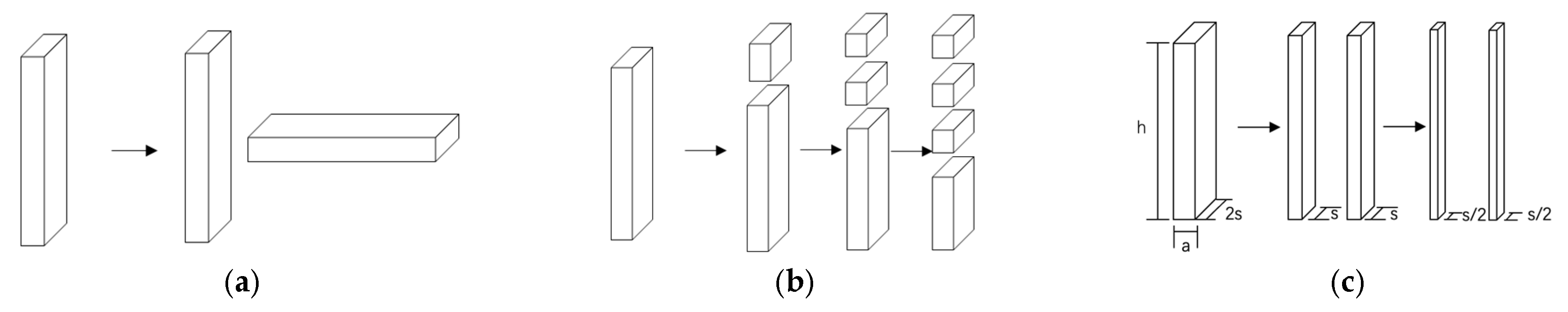

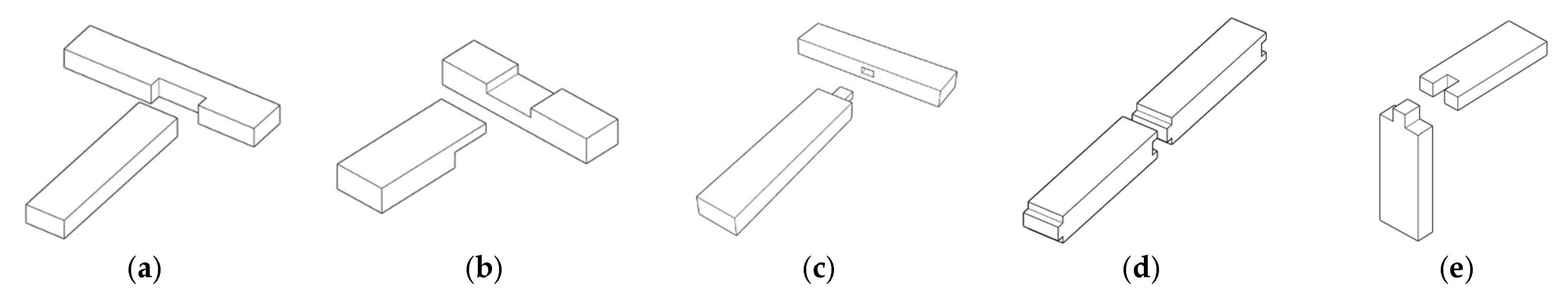

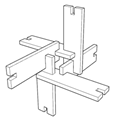

- Component reuseThis dimension presents a strategic response to the issue of component circularity. Three reuse strategies, including full reuse, length reduced reuse, and length preserving flexible reuse, are proposed to explore modular adaptability from the perspective of component length. Joint design, particularly at beam–column connections, is identified as essential for enabling reversibility and supporting circular mechanisms. Further, a modular structural system is conceived as a reflection on circular construction, incorporating standardized modules, detachable joints, and reconfigurable units to enhance adaptability and reuse potential.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Design and Formation Logic

3.1.1. Design with Flexibility

3.1.2. Emphasis on Construction Speed

3.1.3. Module Adaptability

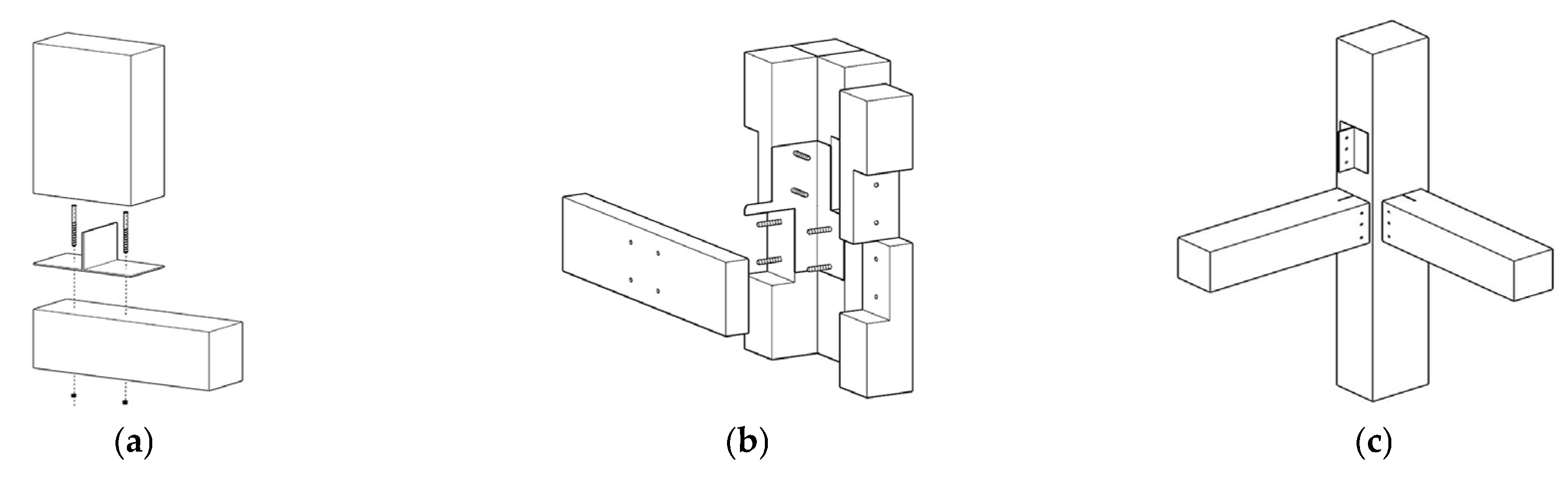

3.2. Joints Typology

3.2.1. Timber Joinery

3.2.2. Metallic Connection

3.2.3. Room-Sized Module Connection

3.3. Structural System Selection

3.4. Prefabrication and Assembly

3.4.1. Standardized Prefabricated Units

3.4.2. Muti-Layered Structure

3.5. Component Reuse

3.5.1. Dimensional Reuse Approaches

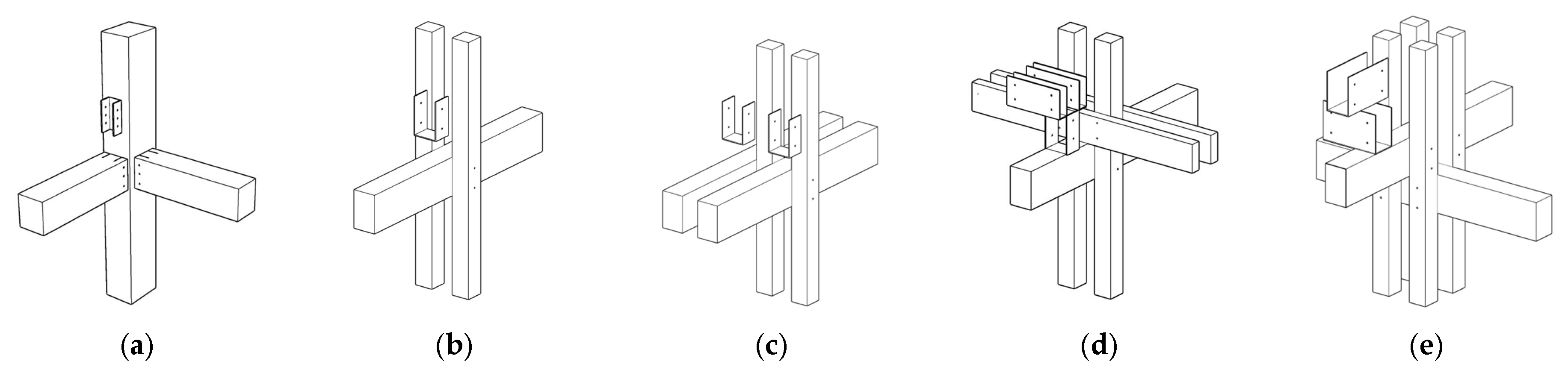

3.5.2. Design of Reusable Joints

3.5.3. Reuse in Timber Structure

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zwerger, K. Wood and Wood Joints: Building Traditions of Europe, Japan and China; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, J. Systems in Timber Engineering: Loadbearing Structures and Component Layers; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.; Kaufmann, J.; Krötsch, S.; Winter, S. Manual of Multistorey Timber Construction; Detail: München, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. Traditional Chinese Architecture: Twelve Essays; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, N.S. Chinese Architecture: A History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaldrake, W.H. Architecture and Authority in Japan; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchioni, N.; Degl’Innocenti, M.; Mannucci, F.; Stefani, I.; Lazzeri, S.; Caciagli, S. Timber structures of Florence cathedral: Wood species identification, technological implications and their forest origin. Forests 2023, 14, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieraad, I. Bringing nostalgia home: Switzerland and the Swiss chalet. Archit. Cult. 2018, 6, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huß, W.; Kaufmann, M.; Merz, K. Building in Timber-Room Modules; Detail: München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, K. Metabolism in architecture. In Metabolism in Architecture; Studio Vista: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Mao, C.; Li, Z.; Li, K. Life-cycle energy analysis of prefabricated building components: An input-output-based hybrid model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.V.; Craig, N. Wood in Construction—25 Cases of Nordic Good Practice; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.M.; Reynolds, T.P.S. Lightweighting with Timber: An opportunity for more sustainable urban densification. J. Archit. Eng. 2018, 24, 02518001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, I.C.; Farquhar, G.D.; Fasham, M.J.R.; Goulden, M.L.; Heimann, M.; Jaramillo, V.J.; Kheshgi, H.S.; Le Quere, C.; Scholes, R.J.; Wallace, D.W.R.; et al. The carbon cycle and atmospheric carbon dioxide. In Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxha, E.; Passer, A.; Saade, M.R.M.; Trigaux, D.; Shuttleworth, A.; Pittau, F.; Allacker, K.; Habert, G. Biogenic carbon in buildings: A critical overview of LCA methods. Build. Cities 2020, 1, 504–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.B.; Lam, F.C.F.; Cole, R.J. A comparative cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment of mid-rise office building construction alternatives: Laminated timber or reinforced concrete. Buildings 2012, 2, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñaloza, D.; Erlandsson, M.; Falk, A. Exploring the climate impact effects of increased use of bio-based materials in buildings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeska, S.; Pascha, K.S. Emergent Timber Technologies: Materials, Structures, Engineering, Projects; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staib, G.; Dörrhöfer, A.; Rosenthal, M. Components and Systems: Modular Construction–Design, Structure, New Technologies; Birkhäuser: München, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung-Klatte, S.; Hasselbach, R.; Knaack, U. Prefabricated Systems: Principles of Construction; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncheva, T.; Bradley, F. Multifaceted productivity comparison of off-site timber manufacturing strategies in mainland Europe and the United Kingdom. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.; Ogden, R.; Goodier, C. Design in Modular Construction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalova, E.M.; Generalov, V.P.; Kuznetsova, A.A. Modular buildings in modern construction. Procedia Eng. 2016, 153, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrazi, M.; Eldeib, S.; Prion, H. Experimental evaluation of an orthotropic, monolithic, modular wooden-dome structural system. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2008, 35, 1163–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E. Prefab Architecture: A Guide to Modular Design and Construction; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Andersen, L.V.; Hudert, M.M. The potential contribution of modular volumetric timber buildings to circular construction: A state-of-the-art review based on literature and 60 case studies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Su, S.; Li, L. Advancing timber construction: Historical growth, research frontiers, and time series forecasting. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 2479–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Riggio, M.; Jahedi, S.; Fischer, E.C.; Muszynski, L.; Luo, Z. A Review of Modular Cross Laminated Timber Construction: Implications for Temporary Housing in Seismic Areas. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, G.; Santi, G. Sustainability of temporary housing in post-disaster scenarios: A requirement-based design strategy. Buildings 2023, 13, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavric, I.; Fragiacomo, M.; Ceccotti, A. Cyclic behaviour of typical metal connectors for cross-laminated (CLT) structures. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 1841–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, M.; Bettarello, F.; Ferluga, A.; Marsich, L.; Schmid, C.; Fausti, P. Acoustic of lightweight timber buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, R.; Barber, D.; Wolski, A. Fire Safety Challenges of Tall Wood Buildings; National Fire Protection Research Foundation: Quincy, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Ottenhaus, L.-M.; Leardini, P.; Jockwer, R. Performance of reversible timber connections in Australian light timber framed panelised construction. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 61, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, C.; Gordon, M.; Muster, M.; Kastner, F.; Grönquist, P.; Frangi, A.; Langenberg, S.; De Wolf, C. Design for and from disassembly with timber elements: Strategies based on two case studies from Switzerland. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1307632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Gu, H.; Bergman, R.; Kelley, S.S. Comparative life-cycle assessment of a mass timber building and concrete alternative. Wood Fiber Sci. 2020, 52, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuma, K. The relativity of materials. JA Jpn. Archit. 2000, 38, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kuma, K. Kengo Kuma: My Life as an Architect in Tokyo; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bognar, B.; Kuma, K. Material Immaterial: The New Work of Kengo Kuma; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Imperadori, M.; Clozza, M.; Vanossi, A.; Brunone, F. Digital design and wooden architecture for arte sella land art park. In Digital Transformation of the Design, Construction and Management Processes of the Built Environment; Daniotti, B., Gianinetto, M., Della Torre, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasner, B.; Ott, S. Wonder Wood: A Favorite Material for Design, Architecture and Art; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengo Kuma & Associates; College of Environmental Design UC Berkeley. Nest We Grow. ArchDaily. 29 January 2015. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/592660/nest-we-grow-college-of-environmental-design-uc-berkeley-kengo-kuma-and-associates (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kengo Kuma & Associates. Jyubako. Available online: https://kkaa.co.jp/en/project/jyubako/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Malo, K.A.; Abrahamsen, R.B.; Bjertnæs, M.A. Some structural design issues of the 14-storey timber-framed building “Treet” in Norway. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2016, 74, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmisevic, E. Design for Disassembly as a Way to Introduce Sustainable Engineering to Building Design & Construction; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2006; Available online: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:9d2406e5-0cce-4788-8ee0-c19cbf38ea9a (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Fioravanti, A.; Cursi, S.; Piqué, T.; De Luca, F. (Eds.) Digital Wood Design: Innovative Techniques of Representation in Architectural Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantscharowitsch, M.; Kromoser, B. Robotic timber milling: Accuracy assessment for construction applications and comparison to a CNC machine. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 20, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Taggart, J. Tall Wood Buildings: Design, Construction and Performance; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacević, M.; Füssl, J.; Eberhardsteiner, J. A 3D model for knots and related fiber deviations in sawn timber for prediction of mechanical properties of boards. Mater. Des. 2019, 166, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, M.M.; Yıldırım, M.; Dündar, T. Effect of lumber quality grade on the mechanical properties and product costs of cross-laminated timber panels. BioResources 2025, 20, 3519–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, S. Reuse process for timber elements to optimise residual performances in subsequent life cycles. VITRUVIO—Int. J. Archit. Technol. Sustain. 2022, 7, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowledge Transfer Network. Design Innovation for the Circular Economy: The Materials and Design Exchange Project for End-of-Life Building Façades. Available online: https://www.arup.com/globalassets/downloads/insights/facade-design-for-the-circular-economy.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

| Case | Country | Year | Architect | Building Typology | Module Scale | Construction System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SunnyHills | Japan | 2013 | Kengo Kuma & Associates | Commercial | Component-scale | Joinery-based |

| Cidori | Italy | 2007 | Kengo Kuma & Associates | Pavilion/Exhibition | Component-scale | Joinery-based |

| Kodama | Italy | 2018 | Kengo Kuma & Associates | Pavilion/Exhibition | Component-scale | Joinery-based |

| Nine Bridges Golf Resort | South Korea | 2010 | Shigeru Ban Architects | Clubhouse | Component-scale | Hybrid |

| Nest We Grow | Japan | 2014 | Kengo Kuma & Associates (with UC Berkeley CED) | Pavilion/Residential | Component-scale | Hybrid |

| Jyubako | Japan | 2016 | Kengo Kuma & Associates | Pavilion/Residential | Component-scale | Industrial prefabrication |

| Treet | Norway | 2015 | Artec AS | Residential | Room-scale | Industrial prefabrication |

| Modular School | Switzerland | 2012 | Bauart Architekten und Planer AG | Educational | Room-scale | Industrial prefabrication |

| Woodie Student Hostel | Germany | 2017 | Sauerbruch Hutton | Residential | Room-scale | Industrial prefabrication |

| Component Types | Illustration | Designing Features | Advantages | Limitations | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagonal interlocking components |  | Inclined intersections creating complex timber joints | Enhanced structural stability and improved esthetic dynamic appearance | Small span capacity, high fabrication precision required | SunnyHills |

| Orthogonal interlocking components |  | Right-angle timber connections forming an organized framework | Easy to manufacture and standardize | Small span capacity, high fabrication precision required | Cidori |

| Vertical-slot components |  | Vertical slots or notches allow components to interlock perpendicularly | Enables fast assembly and allows disassembly and reuse | Weakened sections, precise slot alignment needed | Kodama |

| Composite components |  | Multiple timber elements joined to form larger cross-sectional units | Larger cross-sections improve the performance | Composite columns with complex joints, low recyclability | Nest We Grow |

| Panel components |  | Prefabricated timber panels of modular dimensions | Simple installation and quick for enclosing spaces and facades | Poor geometric adaptability | Jyubako |

| Curved components |  | Shaped or bent timber elements producing curved or arched geometry | Expressive architectural forms | Costly curved components, complex assembly | Nine Bridges Golf Resort |

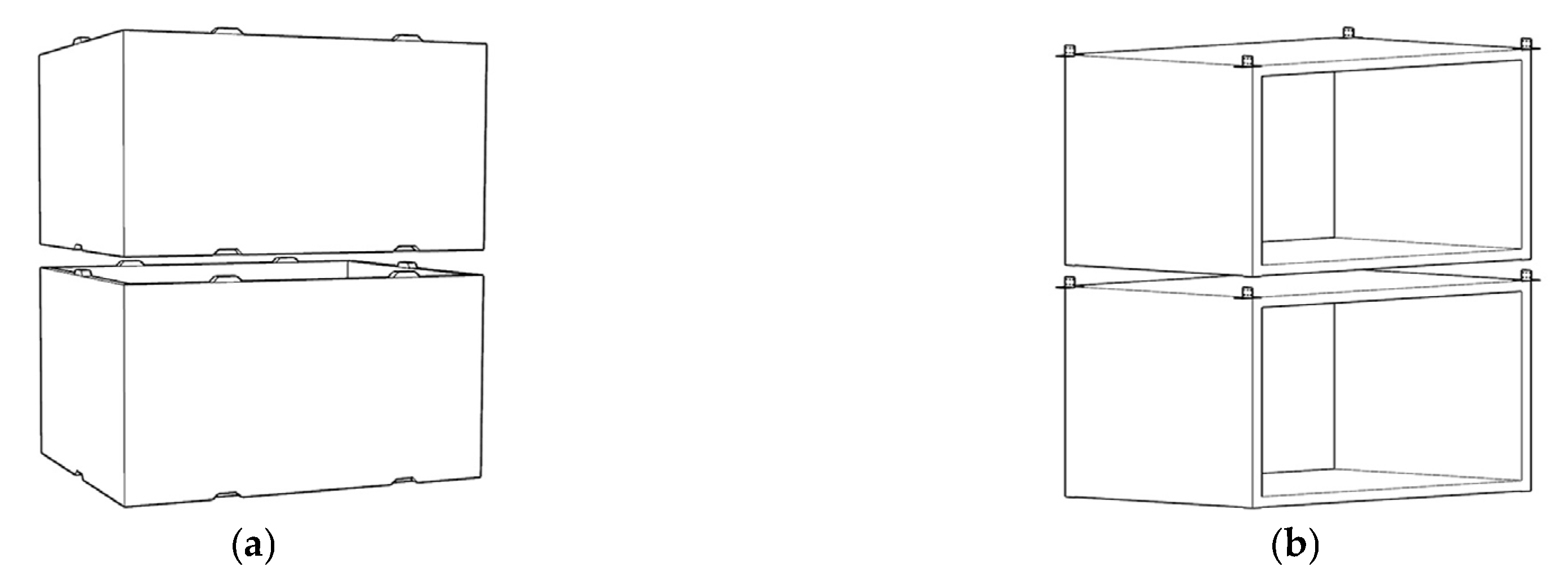

| Component Types | Illustration | Designing Features | Advantages | Limitations | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

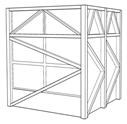

| Room-scale timber modules |  | Stabilized high-rise timber system using stacked prefabricated modules | Fast assembly while ensuring seismic and wind stability | Challenging frame–module coordination, demanding site accuracy | Treet |

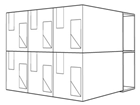

| Room-scale timber modules |  | Square-plan volumetric timber modules with pre-designed openings | Flexible temporary use with rapid assembly | High transport demand | Modular School |

| Room-scale timber modules |  | Room modules with an E-shaped layout and pre-cut façade openings for on-site exterior installation | Flexible module combinations for varied room types and efficient assembly | High transport demand | Woodie Student Hostel |

| Structural System Type | Load Transfer Mechanism | Integration with Architecture | Limitations | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line-supported | Loads distributed along linear components | Enables continuous lattice or grid-like esthetics | Compression-based multidirectional interlocks are less effective in resisting tensile and lateral forces | SunnyHills |

| Point-supported | Envelope itself acts as load-bearing structure | Seamless integration of structure and envelope | Press-fit joints tend to provide lower tensile performance | Cidori |

| Point-supported | Envelope itself acts as load-bearing structure | Interlocking timber components form both skin and structure | Slot-interlocking relies on bearing and frictional contact, and may show reduced tensile and lateral stability due to potential joint separation | Kodama |

| Point-supported | Multiple slender timber columns grouped to act as a structural unit | Organic forms for nature-inspired and complex roof geometries | Curved slender columns mainly carry vertical load, while lateral stability relies on the overall frame | Nine Bridges Golf Resort |

| Point-supported | Composite timber columns reinforced with steel connectors and combined with framing | Defines spatial organization and structural framework | Composite columns rely on joints and the overall frame for lateral stability | Nest We Grow |

| Line-supported | Prefabricated panels as load bearing or envelope elements | Facilitates lightweight, flexible, and temporary construction | Panelized modules provide limited structural stiffness, with stability depending on connectors and modular assembly | Jyubako |

| Hybrid | Modules stacked within a glulam frame which handles lateral and vertical loads | Frame defines building shape and resists forces and modules amplify function | Structural performance relies on the proper interaction between modules and the frame | Treet |

| Line-supported | Loads transferred through wall panels and floors to foundations | Clear spatial zoning and functional modular units | Horizontal resistance relies on module wall action with modest continuity across joints | Modular School |

| Point-supported | Prefabricated volumetric room modules supported at key points | Modular units establish a clear order on the façade | Lateral load transfer mainly relies on limited inter-module joints | Woodie Student Hostel |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Deng, G.; Santi, G.; Montalbano, G.; Liang, Z. A Multi-Layered Framework for Circular Modular Timber Construction: Case Studies on Module Design and Reuse. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410983

Zhang S, Deng G, Santi G, Montalbano G, Liang Z. A Multi-Layered Framework for Circular Modular Timber Construction: Case Studies on Module Design and Reuse. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410983

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Siyi, Guang Deng, Giovanni Santi, Giammarco Montalbano, and Zhihao Liang. 2025. "A Multi-Layered Framework for Circular Modular Timber Construction: Case Studies on Module Design and Reuse" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410983

APA StyleZhang, S., Deng, G., Santi, G., Montalbano, G., & Liang, Z. (2025). A Multi-Layered Framework for Circular Modular Timber Construction: Case Studies on Module Design and Reuse. Sustainability, 17(24), 10983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410983