Tourist Adaptation to Environmental Change: Evidence from Gangshika Glacier for Sustainable Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do environmental changes in glacier tourism affect tourists’ preferences and decision-making?

- (2)

- How does the economic value of glacier tourism evolve under different environmental change scenarios?

2. Materials and Methods

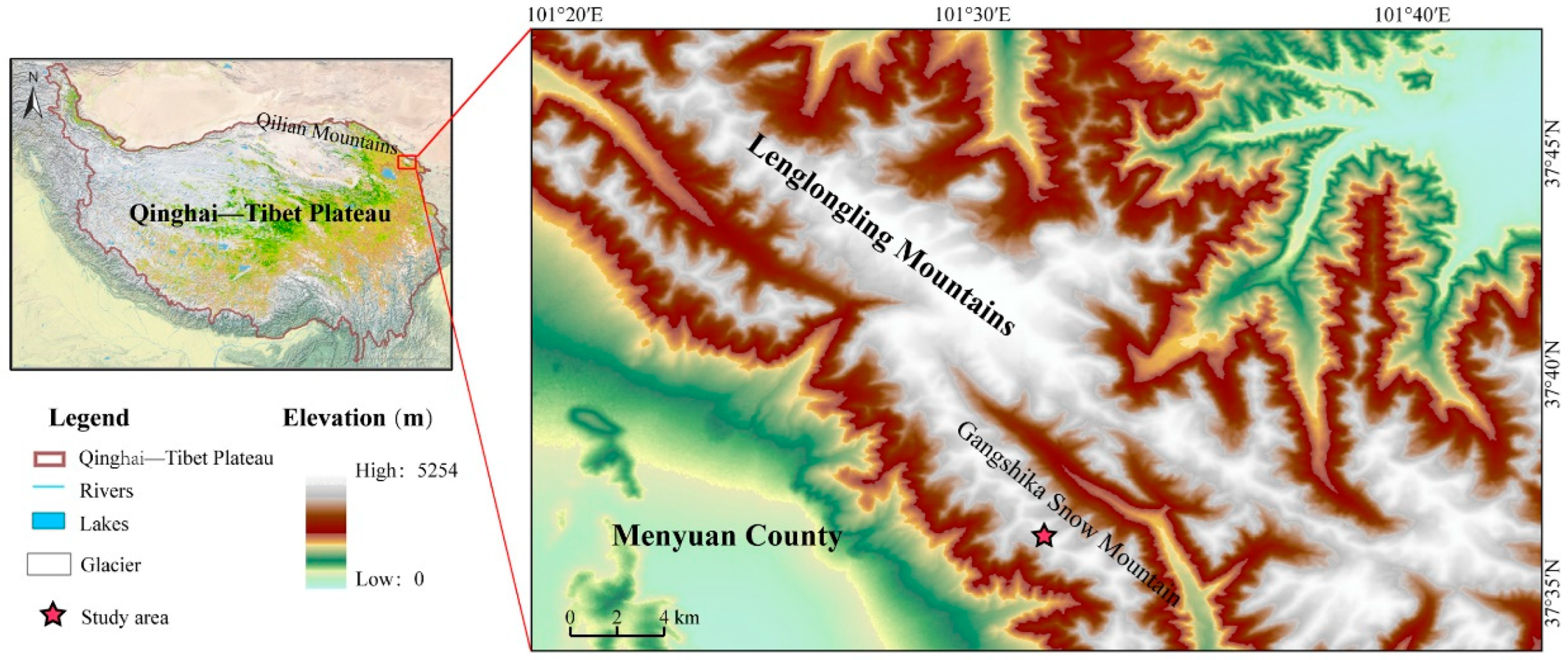

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Sample Size and Sampling Method

2.2.2. Travel Cost Composition and Parameter Settings

- (1)

- Composition of Total Travel Cost

- (2)

- Calculation of Tourist Rate and Spatial Unit Division

- (3)

- Demand Model Construction and Value Assessment

2.2.3. TC-CB Model Construction

- (1)

- Travel Willingness Index and Visit Frequency Prediction

- (2)

- Model Estimation Method and Robustness Handling

- (3)

- CS Estimation

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

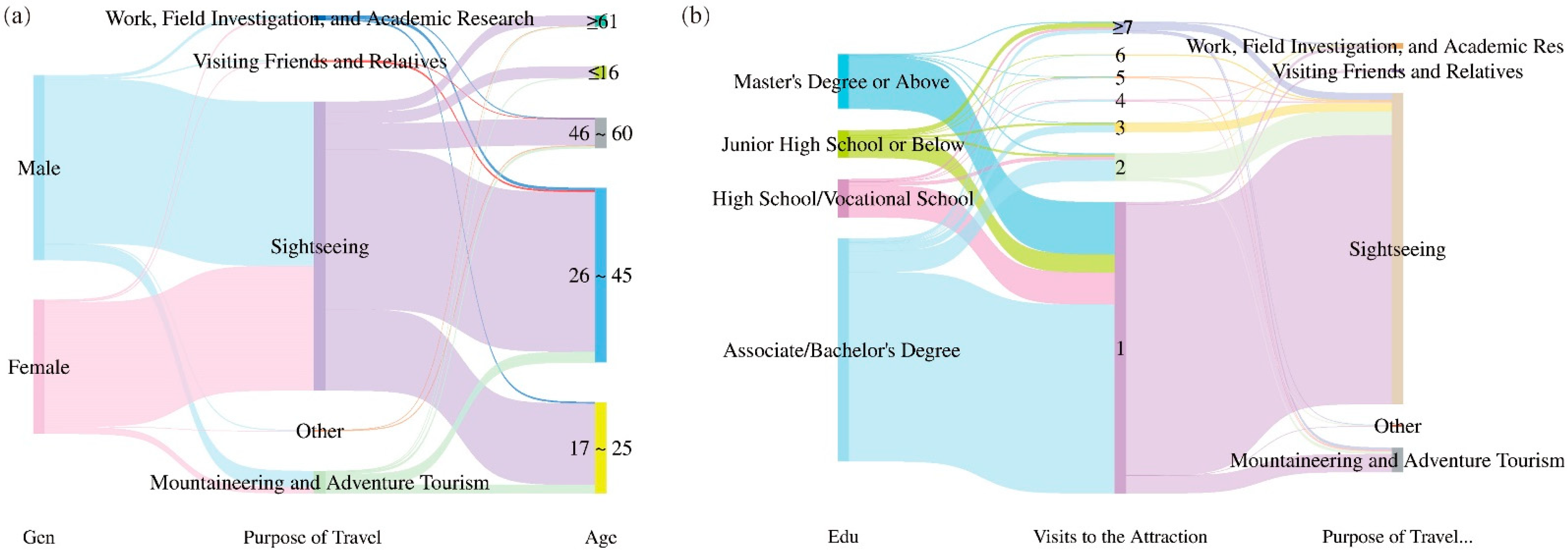

3.1. Questionnaire Survey

3.2. Model Estimation Results

3.2.1. Results of the TCM

3.2.2. Tourist WTP and Environmental Preferences

3.2.3. TC-CB Model Estimation Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance of Findings

4.2. Contributions and Methodological Value

4.3. Methodological Innovation

4.4. Policy Recommendations

- Implementing Differential Pricing and Visitor Capacity Regulation Strategies.

- Strengthening Environmental Quality Maintenance and Climate Adaptation Capacity.

- Establishing an Ecological Compensation Mechanism and Community Co-Governance System.

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

- Sample representativeness and data coverage.

- Limitations of SP data and model assumptions.

- Limitations in Model Structure and Variable Expansion.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TC-CB | Travel Cost-Contingent Behavior model |

| RP | Revealed Preferences |

| SP | Stated Preferences |

| TCM | Travel Cost Method |

| WTP | visitors’ Willingness To Pay |

| CS | Consumer Surplus |

| CVM | Contingent Valuation Method |

| CP | Cost Proportion |

| DWP | Decision Weight Proportion |

| TV | the Total annual tourism Value |

| TWI | Travel Willingness Index |

Appendix A

| Transportation from Your Place of Departure to the First Stop ① Your primary mode of transportation: □Airplane/By Air □Train/High-Speed Rail (HSR) □Motorcycle □On Foot □Self-drive Car (including rented car for self-driving) □Coach/Long-Distance Bus □Public Transportation at the Destination □Other (Please specify): ________ ② Total travel time spent on the road: □Within 30 min □0.5–2 h □2–4 h □4–6 h □6–8 h □Other (Please specify): ________ ③ One-way transportation cost per person (CNY): □0–100 CNY/person (inclusive) □100–200 CNY/person (inclusive) □200–300 CNY/person (inclusive) □300–400 CNY/person (inclusive) □400–500 CNY/person (inclusive) □500–600 CNY/person (inclusive) □600–700 CNY/person (inclusive) □700–800 CNY/person (inclusive) □Other (Please specify): ________ From your previous stop to this scenic area/attraction. ① Your primary mode of transportation: □Airplane/By Air □Train/High-Speed Rail (HSR) □Motorcycle □On Foot □Self-drive Car (including rented car for self-driving) □Coach/Long-Distance Bus □Public Transportation at the Destination □Other (Please specify): ________ ② Total travel time spent on the road: □Within 30 min □0.5–2 h □2–4 h □4–6 h □6–8 h □Other (Please specify): ________ ③ One-way transportation cost per person (CNY): □0–100 CNY/person (inclusive) □100–200 CNY/person (inclusive) □200–300 CNY/person (inclusive) □300–400 CNY/person (inclusive) □400–500 CNY/person (inclusive) □500–600 CNY/person (inclusive) □600–700 CNY/person (inclusive) □700–800 CNY/person (inclusive) □Other (Please specify): ________ |

| Gender | □male □female |

| Age | □≤16 □17–25 □26–45 □46–60 □≥61 |

| Education Level | □Junior secondary school or below □Senior secondary school/vocational secondary education □College diploma or bachelor’s degree □Postgraduate degree or above |

| Occupation | □Student □Manual worker/Skilled labourer □Farmer or herdsman (agricultural and pastoral worker) □Military or police personnel □Civil servant/Government official □Teacher and professional/technical staff □Employee in enterprise or public institution □Self-employed individual (private business owner) □Healthcare practitioner □Service industry worker □Retired person/Pensioner □Other |

| Monthlv lncome (CNY) | □≤3000 □3000~5000 (inclusive) □5000~8000 (inclusive) □8000~10,000 (inclusive) □10,000~20,000 (inclusive) □20,000~30,000 (inclusive) □30,000~50,000 (inclusive) □40,000~50,000 (inclusive) □>50,000 |

References

- Pedersen, V.K.; Egholm, D.L. Glaciations in Response to Climate Variations Preconditioned by Evolving Topography. Nature 2013, 493, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, D.; Yao, T.; Ding, Y.; Ren, J. Introduction to Cryospheric Science; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018; ISBN 978-7-03-058622-3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Jiao, S.; Niu, H. Development patterns and countermeasures of glacier tourism resources in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2012, 27, 1276–1285. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhong, L.; Yu, H. Progress of glacier tourism research and implications. Prog. Geogr. 2019, 38, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, J.T.; Árnason, Þ.; Ólafsdottír, R. Glacier Tourism: A Scoping Review. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 635–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wang, S. Recreational Value of Glacier Tourism Resources: A Travel Cost Analysis for Yulong Snow Mountain. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 1446–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Zhou, L. China’s Glacier Tourism: Potential Evaluation and Spatial Planning. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Park Service. Tourism to Glacier National Park Contributes $548 M to Local Economy; News Release, 23 August 2023. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/news/tourism-to-glacier-national-park-contributes-548m-to-local-economy.htm (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Wang, S.; Che, Y.; Pang, H.; Du, J.; Zhang, Z. Accelerated Changes of Glaciers in the Yulong Snow Mountain, Southeast Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdie, H. Glacier Retreat and Tourism: Insights from New Zealand. Mt. Res. Dev. 2013, 33, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tang, F.; Guo, X.; Chen, H. Development modes and system establishments of ice and snow tourism in China. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2023, 45, 1923–1939. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hugonnet, R.; McNabb, R.; Berthier, E.; Menounos, B.; Nuth, C.; Girod, L.; Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Dussaillant, I.; Brun, F.; et al. Accelerated Global Glacier Mass Loss in the Early Twenty-First Century. Nature 2021, 592, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, M.; Jakob, L.; Dussaillant, I.; Nussbaumer, S.U.; Gourmelen, N.; Dubber, S.; Geruo, A.; Abdullahi, S.; Andreassen, L.M.; Berthier, E.; et al. Community Estimate of Global Glacier Mass Changes from 2000 to 2023. Nature 2025, 639, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFee, M.; Carrivick, J.L.; Quincey, D.J. Rising Snowline Altitudes across Southern Hemisphere Glaciers from 2000 to 2023. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltagliati, L. The Wild Dance of Snow-Lines. Nat. Astron. 2020, 4, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.N.; Marshall, S.J.; Menounos, B. Temperature Mediated Albedo Decline Portends Acceleration of North American Glacier Mass Loss. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Vlug, A.; Piao, S.; Li, F.; Wang, T.; Krinner, G.; Li, L.Z.X.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Li, Y.; et al. Regional and Tele-Connected Impacts of the Tibetan Plateau Surface Darkening. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnajot, A.; Salim, E. The Hauntology of Climate Change: Glacier Retreat and Dark Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Xiao, C.; Chen, D.; Qin, D.; Ding, Y. Cryosphere Services and Human Well-Being. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, E. Travel demand model estimation and its application based on the combined stated and revealed preference methods. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2016, 25, 270–277. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, I.J. Valuing Preferences for Non-Market Goods and Resources. In Sustainable Resource Use and Economic Dynamics; The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 1571-487X. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A.M., III; Joseph, A.H.; Kling, C.L. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-78091-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hanemann, W.M. Valuing the Environment Through Contingent Valuation. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Pattanayak, S.K.; Van Houtven, G.L.; Gelso, B.R. Combining Revealed and Stated Preference Data to Estimate the Nonmarket Value of Ecological Services: An Assessment of the State of the Science. J. Econ. Surv. 2008, 22, 872–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J. Is Hypothetical Bias Universal? Validating Contingent Valuation Responses Using a Binding Public Referendum. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2006, 52, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, R.S.; Loomis, J.B. The Value of Ranch Open Space to Tourists: Combining Observed and Contingent Behavior Data. Growth Change 1999, 30, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandro, P.; De Meo, I.; Grilli, G.; Notaro, S. Valuing Nature-Based Recreation in Forest Areas in Italy: An Application of Travel Cost Method (TCM). J. Leis. Res. 2023, 54, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazka, P.; Abrham, J. Evaluation of Environmental Assets Value on Borneo Using the Travel Cost Method. BioResources 2024, 19, 5811–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haab, T.C.; McConnell, K.E. Valuing Environmental and Natural Resources: The Econometrics of Non-Market Valuation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-84376-543-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wubalem, A.; Woldeamanuel, T.; Nigussie, Z. Economic Valuation of Lake Tana: A Recreational Use Value Estimation through the Travel Cost Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Dupras, J.; Poder, T.G. The Value of Wetlands in Quebec: A Comparison between Contingent Valuation and Choice Experiment. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, L. The Contingent Valuation Method: A Review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Cao, M.; Tang, C.; Ma, Q.; Cao, Y.; Xue, J. Non-use value assessment of the Chongming Dongtan wetland based on the contingent valuation method. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 41, 21–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Z.; Wang, E.; Qiu, Y. The Impact of Environmental Quality Changes on Tourists’ Welfare: Based on Travel Cost and Contingent Behavior Data. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 38, 123–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feuillet, T.; Sourp, E. Geomorphological Heritage of the Pyrenees National Park (France): Assessment, Clustering, and Promotion of Geomorphosites. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.J.; Wilson, J.; Espiner, S.; Purdie, H.; Lemieux, C.; Dawson, J. Implications of Climate Change for Glacier Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). NASADEM Merged DEM Global 1 Arc Second V001 [Data Set]; NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, W.; Xu, J. The Second Glacier Inventory Dataset of China (Version 1.0) (2006-2011) [Data Set]; National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Yang, Y.; Xu, S.; Song, H. Happy without accompaniment? A study of the effect of inter-generational support on psychological well-being of offspring and relatives in filial tourism. Tour. Sci. 2025, 1–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, Q. Scale Development of Tourists’ Time Perception and Its Impact on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Tour. Trib. 2025, 1–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. The Influence Mechanism of Social Contact on Latent Conflicts in Tourist Destinations: A Comparative Analysis Based on Multi-Stakeholder Perceptions. Master’s Thesis, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, C.G. Sampling Strategies for On-Site Recreation Counts. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2017, 5, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madow, W.G. Elementary Sampling Theory. Technometrics 1968, 10, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezzi, C.; Bateman, I.J.; Ferrini, S. Using Revealed Preferences to Estimate the Value of Travel Time to Recreation Sites. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 67, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesario, F.J. Value of Time in Recreation Benefit Studies. Land Econ. 1976, 52, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, E.; Von Haefen, R.H.; Herriges, J.; Leggett, C.; Lupi, F.; McConnell, K.; Welsh, M.; Domanski, A.; Meade, N. Estimating the Value of Lost Recreation Days from the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 91, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ge, Q. Analysis of the Image of Global Glacier Tourism Destinations from the Perspective of Tourists. Land 2022, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, N. Tourism resource valuation: A case study of Dunhuang. J. Nat. Resour. 2004, 19, 811–817. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhao, T.; Xiang, C. Evaluation on the economic value of ancient city tourist attractions based onTCM-CVM integrated model: A case of Langzhong Ancient City. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 196–201. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, S.; Greene, W. Preference Heterogeneity in Contingent Behaviour Travel Cost Models with On-Site Samples: A Random Parameter vs. a Latent Class Approach. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression Analysis of Count Data, 2nd ed.; Econometric Society Monographs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-107-01416-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe, J.M. Negative Binomial Regression, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-521-19815-8. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh, P. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-203-75373-6. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann, R. (Ed.) Poisson Regression. In Econometric Analysis of Count Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 63–126. ISBN 978-3-540-78389-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the Issuance of the “Measures for the Ethical Review of Science and Technology (Trial Implementation)”; Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023. (In Chinese)

- Chen, F.; Zhang, J. Analysis on capitalization accounting of travel value: A case study of Jiuzhaigou scenic spot. J. Nanjing Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2001, 37, 296–303. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Frauman, E.; Banks, S. Gateway Community Resident Perceptions of Tourism Development: Incorporating Importance-Performance Analysis into a Limits of Acceptable Change Framework. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Herriges, J.A. Convergent Validity of Contingent Behavior Responses in Models of Recreation Demand. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 45, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tourist Characteristics | Description | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 537 | 57.99 |

| female | 389 | 42.01 | |

| Age | ≤16 | 35 | 3.78 |

| 17~25 | 265 | 28.62 | |

| 26~45 | 506 | 54.64 | |

| 46~60 | 87 | 9.40 | |

| ≥61 | 33 | 3.56 | |

| Monthlv lncome (CNY) | ≤3000 | 214 | 23.11 |

| 3000~5000 (inclusive) | 165 | 17.82 | |

| 5000~8000 (inclusive) | 219 | 23.65 | |

| 8000~10,000 (inclusive) | 112 | 12.10 | |

| 10,000~20,000 (inclusive) | 143 | 15.44 | |

| 20,000~30,000 (inclusive) | 47 | 5.08 | |

| 30,000~40,000 (inclusive) | 15 | 1.62 | |

| 40,000~50,000 (inclusive) | 6 | 0.65 | |

| >50,000 | 5 | 0.54 | |

| Education Level | Junior secondary school or below | 74 | 7.99 |

| Senior secondary school/vocational secondary education | 103 | 11.12 | |

| College diploma or bachelor’s degree | 601 | 64.90 | |

| Postgraduate degree or above | 148 | 15.98 | |

| Occupation | Student | 186 | 20.09 |

| Manual worker/Skilled labourer | 17 | 1.84 | |

| Farmer or herdsman (agricultural and pastoral worker) | 18 | 1.94 | |

| Military or police personnel | 11 | 1.19 | |

| Civil servant/Government official | 38 | 4.10 | |

| Teacher and professional/technical staff | 104 | 11.23 | |

| Employee in enterprise or public institution | 307 | 33.15 | |

| Self-employed individual (private business owner) | 65 | 7.02 | |

| Healthcare practitioner | 28 | 3.02 | |

| Service industry worker | 26 | 2.81 | |

| Retired person/Pensioner | 39 | 4.21 | |

| Other | 87 | 9.40 |

| Contrast | Mean Difference | SE | p-Value | 95% CI [Lower, Upper] | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A vs. B | 2.822 | 0.651 | <0.001 | [1.10, 4.54] | Significant |

| A vs. C | 3.781 | 0.526 | <0.001 | [2.39, 5.17] | Significant |

| A vs. D | 3.845 | 0.608 | <0.001 | [2.24, 5.45] | Significant |

| B vs. C | 0.960 | 0.456 | 0.213 | [−0.24, 2.16] | Not significant |

| B vs. D | 1.023 | 0.548 | 0.374 | [−0.43, 2.47] | Not significant |

| C vs. D | 0.063 | 0.392 | 1.000 | [−0.97, 1.10] | Not significant |

| Variable | Type | Min | Max | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual expenses (CNY) | Continuous | 124.70 | 8855.45 | 1105.13 |

| Time Cost (CNY) | Continuous | 7.00 | 18,467.87 | 267.15 |

| Combined/total travel cost (CNY) | Continuous | 144.13 | 26711.54 | 1357.28 |

| Income | Continuous | 2900.00 | 80,000.00 | 9070.09 |

| Age | Continuous | 16.00 | 65.00 | 33.28 |

| Peo | Continuous | 1.00 | 120.00 | 4.69 |

| Gen | Dummy | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.58 |

| Edu | Dummy | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Hrs | Continuous | 0.25 | 735.00 | 7.17 |

| Visits to the Attraction (annual visit count) | Continuous | 1.00 | 30.00 | 1.91 |

| Indicator | Poisson Regression | Negative Binomial Regression | Model Evaluation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient Estimates | −12.1 × 10−5 | −8.6 × 10−5 | NB model coefficients are more stable (lower standard errors) |

| Overdispersion Test | χ2/df = 3.2 | χ2/df = 1.830 | NB model resolves over-dispersion (threshold > 1.5) |

| Residual Std. Deviation | 0.56 | 0.48 | NB model provides a better fit with smaller residual fluctuations |

| AIC/BIC | 1245.7 | 1189.3 | NB model has lower information criteria (indicating a more parsimonious model) |

| p-value | p < 0.05 | p < 0.01 | NB model demonstrates greater coefficient significance |

| pseudo-R2 | 0.121 | 0.208 |

| Payment Rate | Willing | Unwilling | |

| 83.91% | 16.09% | ||

| Payment Motivation | Existence | Heritage | Option Value |

| 62.11% | 30.02% | 7.87% | |

| WTP | Mean (CNY) | Median (CNY) | |

| 40 | 50 | ||

| Indicator Dimension | Glacier Area | Snowline Elevation | Solid Waste in Tourist Site | Shuttle Service Fee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.1 |

| Variable | SP-NB | Pooled-NB | RE-NB | Revealed-NB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | |

| Intercept | 1.162 *** | 0.000 | 1.083 *** | 0.000 | 1.017 *** | 0.000 | 0.925 *** | 0.000 |

| Income | −0.600 × 10−5 | 0.161 | −6.393 × 10−6 | 0.161 | −6.352 × 10−6 ** | 0.005 | −6.309 × 10−6 ** | 0.006 |

| Age | 0.006 * | 0.074 | 0.006 * | 0.074 | 0.006 ** | 0.016 | 0.006 ** | 0.015 |

| Peo | −0.005 | 0.500 | −0.005 | 0.500 | −0.006 | 0.468 | −0.006 | 0.468 |

| Gen | 0.606 *** | 0.000 | 0.606 *** | 0.000 | 0.608 *** | 0.001 | 0.609 *** | 0.001 |

| Edu | −0.961 *** | 0.000 | −0.961 *** | 0.000 | −0.961 *** | 0.000 | −0.961 *** | 0.000 |

| TCD1 | −1.270 × 10−4 ** | 0.006 | −1.183 × 10−4 ** | 0.006 | −1.624 × 10−4 ** | 0.020 | −1.384 × 10−4 | 0.115 |

| EQI × TCD1 | −3.600 × 10−5 ** | 0.006 | −4.732 × 10−5 ** | 0.006 | −3.443 × 10−6 | 0.596 | - | - |

| AIC | 3591.819 | 3591.819 | 6909.410 | 3327.590 | ||||

| Log PL | −1788.910 | −1788.910 | −3445.710 | −1656.800 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Variable | SP-NB | Pooled-NB | RE-NB | Revealed-NB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | |

| Intercept | 0.680 *** | 0.000 | 0.785 *** | 0.000 | 0.809 *** | 0.000 | 0.925 *** | 0.000 |

| Income | −4.261 × 10−6 | 0.403 | −4.000 × 10−6 | 0.403 | −5.074 ×10−6 | 0.142 | −6.309 × 10−6 ** | 0.006 |

| Age | 0.007 * | 0.078 | 0.007 * | 0.077 | 0.006 ** | 0.012 | 0.006 ** | 0.015 |

| Peo | −0.007 | 0.454 | −0.007 | 0.454 | −0.006 | 0.452 | −0.006 | 0.468 |

| Gen | 0.616 *** | 0.000 | 0.616 *** | 0.000 | 0.613 *** | 0.000 | 0.609 *** | 0.001 |

| Edu | −0.968 *** | 0.000 | −0.968 *** | 0.000 | −0.964 *** | 0.000 | −0.961 *** | 0.000 |

| TCD2 | −5.359 ×10−5 * | 0.082 | −6.200 × 10−5 * | 0.083 | −2.001 × 10−4 ** | 0.019 | −1.384 × 10−4 | 0.115 |

| EQI × TCD2 | −2.143 ×10−5 * | 0.083 | −4.000 ×10−6 | 0.126 | −1.956 × 10−4 | 0.096 | - | - |

| AIC | 3041.840 | 3041.840 | 6359.532 | 3327.590 | ||||

| Log PL | −1513.920 | −1513.920 | −3170.766 | −1656.800 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Scenario | Annual Visit Frequency (Visits/Year) | CS (104 CNY/Visit) |

|---|---|---|

| Observed | 1.91 | 1.16 |

| TC-CB model Scenario D1 | 2.29 | 1.41 |

| TC-CB model Scenario D2 | 1.56 | 0.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, N. Tourist Adaptation to Environmental Change: Evidence from Gangshika Glacier for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310808

Lu R, Wang Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Yang D, Jiang Y, Zhao X, Zhao L, Wang N. Tourist Adaptation to Environmental Change: Evidence from Gangshika Glacier for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310808

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Rongzhu, Yixin Wang, Jinqiao Liu, Yuchen Wang, Dan Yang, Yan Jiang, Xiaoyang Zhao, Liqiang Zhao, and Naiang Wang. 2025. "Tourist Adaptation to Environmental Change: Evidence from Gangshika Glacier for Sustainable Tourism" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310808

APA StyleLu, R., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Wang, Y., Yang, D., Jiang, Y., Zhao, X., Zhao, L., & Wang, N. (2025). Tourist Adaptation to Environmental Change: Evidence from Gangshika Glacier for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability, 17(23), 10808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310808