1. Introduction

In organizational research, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is widely recognized as a discretionary, prosocial behavior that critically enhances organizational efficiency and sustainability [

1,

2]. Encompassing behaviors that extend beyond formal job descriptions, OCB has become essential at the organizational level and within team-based collaboration contexts [

3]. In occupational settings characterized by emotional labor and hierarchical structures—such as airline cabin crews—examining the relational and psychological mechanisms that foster OCB is crucial [

4,

5].

While early research typically considered OCB to be a stable dispositional tendency, more recent studies have conceptualized it as a dynamic behavioral pattern shaped by relational contexts, organizational climates, and psychological resources [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Within this line of inquiry, rapport—defined as a form of relational harmony marked by mutual attentiveness, positive affect, and coordinated interaction [

10]—has been identified as a critical antecedent to trust and commitment in organizational settings [

11,

12,

13]. Nevertheless, limited empirical research has examined the multistage processes through which rapport develops into specific organizational behaviors. A parallel research stream emphasizes the importance of psychological capital (PsyCap), a personal resource comprising hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism, as an important driver of employee commitment and growth [

7,

14]. However, few studies have investigated how relational resources such as rapport and trust are transformed into personal resources like PsyCap [

15,

16].

The present study addresses this gap by integrating insights from the job demands–resources (JD-R) model and social exchange theory (SET). According to the JD-R model, job demands typically drain energy and induce strain, whereas job resources buffer these effects and foster engagement and prosocial behaviors [

17,

18]. Job resources extend beyond material support; they also include relational resources such as trust and rapport, as well as personal resources such as PsyCap [

7]. Conversely, SET posits that when employees experience positive interactions or receive resources from relationships, they reciprocate through voluntary behaviors guided by the norm of reciprocity [

19,

20,

21]. Taken together, these perspectives suggest that relational resources are transformed into personal resources, which in turn relate to OCB.

In the Korean cultural context, which is marked by high power distance and collectivism, rapport may manifest as hierarchical respect rather than peer-level emotional closeness [

22]. In such settings, the way rapport relates to trust may differ from Western contexts. Airline crews also face extreme emotional labor, where discretionary behavior such as OCB may be interpreted as normative obligation, raising ethical concerns [

23]. This study thus examined how relational resources help buffer job demands and protect personal psychological resources in emotionally taxing environments. Specifically, it examines the effects of rapport on trust and PsyCap, assessed the effects of trust on PsyCap and OCB, evaluated the impact of PsyCap on OCB, and investigated both the direct effect of rapport on OCB and its sequential mediation through trust and PsyCap. In addition, this study explored whether an employee’s hierarchical position moderates the relationship between rapport and trust, acknowledging that the strength of relational ties may vary across different organizational levels.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Job Demands–Resources Model and Social Exchange Theory

The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model offers a comprehensive framework for explaining how diverse job characteristics influence employee well-being, motivation, and performance through two parallel pathways: the health-impairment process and the motivational process [

17,

18].

Although the JD-R model has often been empirically operationalized through the interaction between job demands and resources, such an approach reflects only one facet of the theory. Recent scholarship argues that relying solely on the interaction pathway overlooks the broader motivational logic of JD-R, which encompasses resource-based mechanisms describing how different forms of resources accumulate, reinforce, and transform over time [

24,

25,

26].

From this resource-accumulation perspective, job, social, and personal resources interact dynamically to generate self-sustaining gain spirals that enhance engagement, resilience, and prosocial behavior [

27,

28]. This process highlights that resources do not function in isolation but evolve through continuous exchanges and reinforcements across levels.

Recent developments in JD-R theory underscore that employees’ positive psychological states—such as PsyCap, optimism, and self-efficacy—serve as crucial personal resources mediating the relationship between contextual resources and adaptive outcomes [

14,

27,

29]. Thus, focusing on the conversion of relational resources into psychological resources is consistent with the JD-R’s motivational process and reflects the model’s expanded explanatory potential in contemporary organizational contexts.

Nevertheless, prior JD-R studies incorporating relational dynamics have often neglected the underlying social and psychological mechanisms by which resources are internalized and maintained. To address this conceptual limitation, the present study integrates SET as a complementary lens.

SET posits that interpersonal relationships are governed by the norm of reciprocity, in which individuals respond to favorable treatment with prosocial and cooperative actions [

19,

20]. While this principle has been widely applied to explain organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), many studies have adopted a narrow, transactional perspective—assuming that employees merely reciprocate benefits with positive behaviors [

16,

30]. Although such an approach captures surface-level exchanges, it overlooks the psychological transformation through which social experiences evolve into enduring motivational states.

Recent extensions of SET have sought to overcome this limitation by introducing trust and psychological capital as exchange-stabilizing resources that transform episodic reciprocity into sustainable commitment and motivation [

14,

15,

31]. These works suggest that SET should not be confined to a theory of behavioral exchange but reinterpreted as a process of psychological internalization, wherein relational experiences generate intrinsic motivational resources [

19,

20]. Within this framework, rapport functions as an initiating social resource that facilitates the cognitive internalization of exchange experiences into trust, which subsequently develops into psychological resources such as PsyCap. Through this sequence, positive relational experiences are consolidated into motivational capital, sustaining long-term commitment and discretionary prosocial behavior.

By integrating JD-R and SET, this study provides a multi-level explanation of how external social interactions are connected to internal motivational capacities.

The JD-R model elucidates the structural process through which resources accumulate and expand, whereas SET explains the motivational rationale that drives individuals to internalize these resources into enduring commitment. Together, the two frameworks articulate a sequential relationship—rather than a causal one—between relational and psychological resources, positioning rapport, trust, and PsyCap as interdependent components within the broader system of sustainable organizational behavior.

Accordingly, this study adopts a resource-conversion perspective to examine how interpersonal rapport is linked to trust and PsyCap and, in turn, to OCB. This approach extends the JD-R model beyond its traditional interaction paradigm and reconceptualizes SET as a dynamic mechanism of psychological internalization that underpins sustainable, prosocial conduct in organizations.

2.2. OCB and Sustainability

OCB refers to voluntary actions that extend beyond formal job requirements and contribute to the ethical and social functioning of organizations [

1,

32]. Early studies primarily regarded OCB as a behavioral consequence of individual dispositions, work attitudes, or leadership perceptions [

33,

34]. Over time, scholars began to recognize that OCB plays a much broader role, functioning as a behavioral foundation for organizational sustainability. Rather than being a mere reflection of existing performance, OCB is now understood as a catalyst for long-term viability and ethical continuity within organizations [

35,

36].

In the traditional Human Resource Management (HRM) literature, OCB has often been discussed as a mechanism for improving short-term outcomes such as efficiency and employee commitment. In contrast, the emerging perspective of Sustainable HRM redefines human resources as renewable capital that should be nurtured and replenished instead of depleted [

35,

36,

37]. Bowen and Ostroff [

36] argued that the strength of an HRM system—its consistency, distinctiveness, and internal alignment—creates shared interpretations among employees that sustain cooperative and prosocial behavior over time. Bansal and Song [

37] expanded this discussion by differentiating sustainability from corporate social responsibility, emphasizing that true sustainability rests upon the preservation of psychological resources and the maintenance of ethical conduct across time. Building on this framework, Bučiūnienė and Goštautaitė [

35] found that sustainable HRM practices in educational institutions enhance both employee well-being and citizenship behaviors, suggesting that supportive human resource systems cultivate enduring organizational health. Taken together, these studies indicate that OCB should not be interpreted as a by-product of performance but as a dynamic process through which social and psychological resources are renewed and circulated within the organization.

The social capital perspective adds another dimension to this argument by emphasizing the relational mechanisms underlying OCB. Trust, reciprocity, and organizational identification enable employees to internalize shared goals and norms, thereby fostering discretionary cooperation [

38,

39]. Despite this, many prior studies have treated social capital merely as a precursor to citizenship behavior without examining the reciprocal dynamic in which OCB regenerates and expands the very social capital it depends on. Recent research has begun to recognize this cyclical process. For instance, studies in hospitality and education settings show that when organizations provide supportive and fair environments, psychological resources and OCB become central channels through which human resource practices contribute to sustainable employee well-being and organizational outcomes [

8,

29]. Similarly, Abdou et al. [

40] showed that green citizenship behaviors strengthen employees’ sense of belonging and lead to sustainable competitive advantage in the hospitality industry. These findings collectively highlight that citizenship behavior not only draws from but also reproduces social capital through a self-reinforcing mechanism that lies at the heart of social sustainability. The concept of sustainability has progressively evolved beyond environmental and economic dimensions to encompass psychological and ethical aspects as well [

35,

37]. However, many studies still overlook how employees’ moral identity, intrinsic motivation, and resilience contribute to the long-term endurance of organizations.

Recent sustainable HRM research demonstrates that supportive and ethically oriented management practices build trust and strengthen employees’ sense of identification, which in turn promotes behavioral continuity and resilience over time [

35,

36]. Consistent with this view, Varga et al. [

41] found that wellness programs and OCB interact to mitigate burnout and enhance psychological resilience, ultimately improving collective well-being and cohesion.

Together, these insights suggest that citizenship behaviors are embedded within a broader ethical system of sustainability—one that sustains organizational integrity and vitality over time. OCB therefore represents a behavioral expression of organizational sustainability.

It reinforces social relationships that form the foundation of cooperative work, cultivates community resilience grounded in trust and shared identity, and accumulates moral and psychological capital that ensures long-term ethical and emotional stability. In this sense, OCB serves as a central mechanism through which organizations sustain their social, ethical, and psychological well-being.

By integrating Sustainable HRM and Social Capital Theory, this study positions OCB as the conceptual bridge linking individual motivation with collective sustainability, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of how organizations preserve both performance and humanity [

35,

36,

37,

41,

42].

2.3. Rapport

Rapport represents a relational resource characterized by emotional closeness and mutual understanding between individuals. Such rapport is central to shaping the quality of social interactions within organizations and service contexts [

10,

43].

Prior studies have consistently shown that rapport strengthens trust, satisfaction, and commitment [

11,

44]; however, most have treated rapport merely as a by-product of affective warmth, offering limited insight into how it operates as a motivational resource or under which conditions its effects vary. This narrow treatment restricts theoretical understanding of how rapport functions as a resource and through which mechanisms it contributes to behavioral outcomes.

Some scholars have argued that rapport should be viewed not as a derivative of positive emotion but as an antecedent resource that cultivates psychological safety and efficacy [

13,

15,

30]. Through trust-based interactions, rapport facilitates the development of optimism, resilience, and hope—key dimensions of PsyCap—and thereby acts as a psychological conduit linking social experience to intrinsic motivation [

4].

However, other researchers have cautioned that rapport can have ambivalent effects. Barry, Olekalns, and Rees [

43] highlighted that sustained interpersonal engagement can intensify emotional labor and ethical tension in service work, while Yagil and Medler-Liraz [

45] demonstrated that maintaining authenticity in service encounters may heighten emotional fatigue. Similarly, Park and Kim [

46] found that among nursing professionals, rapport may increase the demand for emotional labor and foster excessive relational expectations, ultimately leading to exhaustion.

These contrasting findings suggest that rapport’s outcomes are contingent on individual emotional capacity and organizational context, underscoring the need to conceptualize rapport as a context-sensitive, dual-valence resource rather than a uniformly positive phenomenon.

From a JD-R perspective, rapport functions as a relational resource that buffers the adverse influence of job demands [

17], while from a SET standpoint, it serves as a social catalyst that activates reciprocity norms reinforcing trust and discretionary behavior [

20]. Together, these perspectives suggest that rapport operates simultaneously as a protective and motivational resource, shaping how employees respond to both pressures and relational expectations in organizational settings. Yet most prior studies have treated these frameworks in parallel, overlooking how rapport is converted from a social to a psychological resource—a dynamic mechanism central to understanding sustainable motivation.

Accordingly, the present study reinterprets rapport not as an emotional outcome but as a starting point of motivational resource conversion. Rapport initiates a sequential process in which interpersonal exchanges are internalized into trust and subsequently transformed into psychological capital, ultimately linked to OCB. This approach reframes rapport as a strategic relational asset that sustains both social and psychological dimensions of organizational sustainability.

By empirically examining rapport’s indirect influence on OCB through trust and PsyCap, this study aims to contribute to an expanded integration of JD-R and SET, demonstrating how relational experiences evolve into enduring motivational and prosocial engagement within organizations.

2.4. Trust

Trust constitutes a core relational capital grounded in the belief that others’ intentions and actions are benevolent, reliable, and oriented toward mutual benefit [

39,

47]. Within organizations, trust operates at multiple levels—between supervisors and subordinates, among colleagues, and across teams—and serves as the foundation for cooperation, communication efficiency, and psychological safety [

16,

35]. Although trust is widely recognized as a catalyst for collaboration and performance, prior studies have tended to emphasize its beneficial effects rather than examine its underlying mechanisms or the conditions under which those effects may vary.

From an integrative theoretical standpoint, trust represents both a social and psychological resource that links interpersonal experience to sustainable behavioral engagement. Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated its positive role: trust fosters information sharing, reduces defensive communication, and enhances organizational identification [

15,

48]. Employees who trust their leaders and peers are more inclined to engage in OCB because trust activates reciprocity norms that motivate voluntary and cooperative actions [

20,

21]. Similarly, in service and hospitality contexts, trust has been shown to mediate the relationship between responsible corporate practices and prosocial intentions, reinforcing long-term organizational commitment [

3,

25,

49].

However, a purely affirmative view of trust overlooks its dual nature. As Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman [

31] argued, trust inherently involves vulnerability—a willingness to accept potential risk in pursuit of relational gains. When such vulnerability is misplaced or unreciprocated, trust can evolve into dependency or complacency, suppressing constructive dissent and reducing adaptive capacity [

20].

Meta-analytic evidence shows that the attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of trust are highly sensitive to perceptions of fairness and contextual cues [

30,

50]. Empirical studies in service settings similarly indicate that when employees experience low organizational justice or feel unfairly treated, trust erodes and OCB tends to decline rather than flourish [

38,

39]. These findings suggest that trust’s outcomes are context-dependent, moderated by relational climate and organizational justice.

Viewed through the JD-R framework, trust acts as a motivational resource that enhances engagement and buffers stress by creating psychological safety [

17,

48]. It helps employees interpret work demands as challenges rather than threats, thereby sustaining their well-being and energy. From the SET perspective, trust functions as an exchange stabilizer: perceptions of fairness and support reinforce prosocial reciprocity, transforming situational exchanges into enduring relational commitments [

19,

20].

Trust thus bridges the external (social) and internal (psychological) dimensions of motivation, facilitating the accumulation of PsyCap—optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy [

29]. This psychological enrichment contributes to employees’ persistence and adaptability, aligning trust with the principles of organizational sustainability. Nevertheless, excessive or blind trust may hinder innovation and accountability. Overreliance on interpersonal goodwill can obscure performance issues, foster conformity, and inhibit learning from failure [

20]. Accordingly, trust should not be idealized as an inherently positive construct but instead understood as a conditional and dynamic resource that requires balance between confidence and critical vigilance. Recognizing this complexity, the present study conceptualizes trust as both a mediating psychological mechanism and a contextual moderator that determines whether relational experiences translate into sustained motivational capital and discretionary behavior.

By situating trust at the intersection of JD-R and SET, this study extends existing theory by illustrating how trust operates as a conversion node—transforming social resources into internalized psychological strength that supports long-term, prosocial engagement.

2.5. Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

PsyCap represents an internal positive resource that enables employees to navigate challenges and uncertainties inherent in contemporary work environments. Comprising hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism [

7,

31], PsyCap embodies a proactive mindset that fosters sustainable motivation and engagement without reliance on external rewards [

22,

51]. Unlike stable personality traits, it is state-like and developable, cultivated through experience and training, which positions it as a central construct in sustainable human resource management (HRM) and positive organizational behavior [

52,

53].

Earlier studies consistently demonstrated that PsyCap is positively related to job satisfaction, commitment, and performance [

14,

54], while mediating the mitigation of stress and burnout [

55]. At a broader level, it also enhances collective optimism and resilience, reinforcing trust and social sustainability within organizations [

8]. These findings suggest that PsyCap acts not merely as an individual coping mechanism but as a transformational conduit linking social and psychological sustainability. Through this perspective, PsyCap can be understood as the psychological manifestation of accumulated social exchanges, representing the internalized form of support, recognition, and trust developed through ongoing interpersonal interactions.

Nevertheless, the recent literature cautions against an uncritical acceptance of PsyCap’s benefits. For example, Bogler and Somech [

56] showed that OCB is jointly shaped by employees’ psychological capital and team-level resources, suggesting that the behavioral impact of PsyCap depends on the surrounding social and structural context rather than operating in isolation. Moreover, Mielly et al. [

57] warn that overemphasis on PsyCap may inadvertently pressure employees to internalize emotional norms, thereby legitimizing exploitative emotional labor and masking systemic stressors. These findings underscore the need for a balanced understanding of PsyCap that incorporates both its motivational potential and its ethical boundaries. Thus, PsyCap should not be viewed as an unquestioned remedy for organizational strain, but as a conditional psychological resource whose impact depends on the surrounding relational and cultural environment.

From a JD-R perspective, PsyCap functions as the key mechanism through which relational resources such as rapport and trust are transformed into personal resources [

18]. This process captures how social support and mutual confidence evolve into self-efficacy and optimism, forming a chain of resource conversion that sustains engagement and discretionary behavior. Through this lens, PsyCap serves as the psychological embodiment of the JD-R’s motivational process, facilitating the reinforcement and renewal of internal resources that sustain organizational vitality [

57,

58].

Meanwhile, within the framework of SET, PsyCap represents the culmination of internalized reciprocity, meaning that the experience of being trusted and supported crystallizes into intrinsic motivation. In this way, PsyCap functions as the psychological link that connects the affective warmth generated through rapport and the cognitive stability provided by trust to sustained pro-organizational behavior such as OCB. Accordingly, this study positions PsyCap as the central mediator in the sequential pathway from rapport to trust and ultimately to OCB. By examining how psychological resources develop through the internalization of social exchanges, the present model offers a holistic view of resource dynamics that integrate personal well-being with broader organizational sustainability.

2.6. Relationships Among Rapport, Trust, and Psychological Capital

Rapport represents a key relational resource that is associated with psychological safety and mutual respect within organizations [

10]. In service environments characterized by frequent emotional exchanges, rapport enhances affective stability and predictability, thereby serving as the emotional basis for trust [

11,

44]. Trust, defined as a cognitive belief in another’s reliability, integrity, and benevolence [

47], facilitates long-term collaboration and discretionary behaviors that sustain organizational functioning [

38].

However, several scholars have criticized the conceptual overlap between rapport and trust, arguing that empirical studies often conflate these constructs, blurring their temporal and functional distinction [

59,

60]. In service contexts, affect-based rapport and cognition-based trust may operate within the same measurement domain, producing spurious correlations. To address this limitation, the present study delineates the temporal, functional, and cognitive distinctions between the two. Rapport is an affective, short-term connection that emerges in the early phase of interaction, evoking expectations of goodwill [

61]. In contrast, trust develops through repeated evaluations of consistency and reliability, functioning as a higher-order relational capital essential for enduring cooperation [

62,

63]. Thus, rapport is positioned as an emotional antecedent that triggers the cognitive accumulation of trust.

From the JD-R perspective, rapport operates as a relational resource that is associated with the development of personal resources such as PsyCap [

18,

64]. Yet, JD-R theory itself does not prescribe the causal ordering among resources [

65], necessitating complementary theoretical grounding. Applying Social Exchange Theory (SET), this study conceptualizes rapport as an emotional resource that precedes trust, reinforcing reciprocal motivation through the norm of reciprocity [

27]. In this view, positive relational experiences generated by rapport elicit reciprocal cognitive assurance manifested as trust.

Beyond its association with trust, rapport has been linked to psychological capital—a composite of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy—by cultivating a psychologically supportive environment [

41,

66,

67]. Nevertheless, some scholars have cautioned that relational experiences do not automatically enhance PsyCap; rather, their quality and persistence moderate this effect [

68]. Transient rapport may improve emotional comfort but may fall short in generating cognitive resources like efficacy or resilience [

69]. Consequently, this study positions rapport’s sustained and consistent quality as a precondition for PsyCap development, interpreting this process as a resource conversion mechanism within the JD-R framework.

Collectively, the sequential pathway of rapport–trust–PsyCap explicates how relational resources are internalized as psychological resources, promoting sustainable organizational functioning and human resource well-being. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. Rapport will be significantly and positively related to trust.

H2. Rapport will be significantly and positively related to psychological capital.

2.7. Rapport and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Rapport improves coworker interactions, a sense of belonging, and willingness to collaborate. These relational foundations can serve as motivational drivers of OCB, such as organizational attachment and team orientation [

70,

71]. In service industries with high levels of emotional labor, rapport helps mitigate emotional fatigue, preserving psychological resources that facilitate discretionary behaviors [

12,

72].

Nelson et al. [

11] further observed that rapport-based interactions provide an “optimal organizational experience,” reflected in voluntary commitment and prosocial engagement. However, other studies have argued that rapport may not exert a direct effect on OCB, but rather functions through mediating variables such as trust or psychological capital [

29,

46]. This perspective implies that the emotional quality of interpersonal relationships alone may not sufficiently explain discretionary behaviors unless these interactions also foster a sense of security and internal psychological resources over time.

Moreover, the temporal nature of rapport—its variability and potential fragility—raises concerns about its sustainability as a sole predictor of OCB. Short-term rapport may elicit immediate positive affect but may be insufficient to generate the stable behavioral commitment required for consistent organizational citizenship [

41]. For this reason, some scholars have emphasized the importance of rapport continuity and depth as a prerequisite for sustained prosocial behaviors, particularly when aligned with broader relational constructs such as trust and psychological capital [

55,

58].

From the perspective of the JD-R model, rapport functions as a relational resource that mitigates the negative effects of job demands and promotes constructive behaviors [

73]. Furthermore, according to the norm of reciprocity in SET, positive experiences derived from rapport can trigger reciprocal trust and voluntary contributions [

27]. Taken together, these findings suggest that while rapport may not independently account for all forms of OCB, it acts as a crucial relational enabler that supports the development of trust, psychological resources, and ultimately sustainable extra-role behavior.

H3. Rapport will be significantly and positively related to OCB.

2.8. Trust, Psychological Capital, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Trust is closely associated with OCB, encouraging employees to collaborate voluntarily and pursue collective goals [

16,

39]. According to SET, employees who experience positive relationships built on trust reciprocate through behaviors that exceed formal job duties, consistent with the norm of reciprocity [

20,

21]. Trust is grounded in mutual respect, fairness, and care, motivating employees to align their interests with organizational objectives and contribute voluntarily [

16,

32,

42]

In addition, PsyCap, encompassing hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism, has emerged as a salient personal resource that facilitates the enactment of OCB [

29,

66]. Employees with high PsyCap tend to approach challenges proactively and maintain sustained effort toward work goals, making them more likely to engage in constructive, cooperative behaviors [

38]. Trust and PsyCap are conceptually distinct but functionally complementary in shaping OCB: while trust promotes relational safety, PsyCap reflects internalized confidence to act beyond required duties.

However, this association warrants a more critical perspective. Some studies suggest that trust alone may not be directly related to sustained OCB unless employees perceive alignment with organizational values or fairness in reward systems [

50,

74]. Similarly, PsyCap’s impact on OCB can diminish under high work strain or resource depletion, indicating a conditional pathway [

30]. Thus, trust and PsyCap may not be sufficient conditions but rather necessary precursors whose effectiveness depends on contextual moderators such as leadership climate or perceived organizational support.

H4. Trust will be significantly and positively related to OCB.

H5. Psychological capital will be significantly and positively related to OCB.

2.9. Trust and Psychological Capital

Trust is closely associated with higher levels of PsyCap. When employees experience trust, they feel psychologically safe, which boosts their hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and resilience [

29,

43,

67]. In research on the hospitality sector, Wang and Guan [

29] demonstrated an indirect relationship between workplace trust and OCB through PsyCap This finding supports for the sequential mediation path proposed in this study, in which rapport fosters trust, trust enhances PsyCap, and PsyCap ultimately facilitates OCB.

Similarly, Yildiz, H. (2019) [

75] empirically validated the relationship between trust and PsyCap, as well as its association with OCB in service settings. Notably, their study suggested that downward trust (from leaders to employees) and upward trust (from employees to leaders) may function through distinct mechanisms, underscoring the interactive and multi-dimensional nature of trust. Liu et al. (2022) [

76], focusing on public-sector educators, found that higher levels of PsyCap significantly increased OCB, with organizational trust serving as a reinforcing moderator in this relationship.

However, this relationship is not without critical qualifications. Hobfoll et al. (2018) [

77] cautioned that contextual factors such as leadership quality or perceptions of organizational justice may influence the strength of the relationship between trust and PsyCap or weaken the motivational linkage from PsyCap to OCB. This implies that trust and PsyCap should be treated as contingent resources rather than assuming a direct, linear progression.

In this regard, the present study conceptualized trust as a key relational precursor of PsyCap while acknowledging potential boundary conditions that may affect resource internalization. The integration of the JD-R model and SET offers a robust framework for examining the conditions under which trust facilitates PsyCap development.

H6. Trust will be significantly and positively related to psychological capital.

2.10. Moderating Role of Position on the Rapport–Trust Relationship

Rapport and trust are widely recognized as positively associated in organizational contexts. However, the strength of this association may vary by hierarchical position, especially in emotionally intensive service environments. Prior research suggests that lower-ranking employees tend to interpret rapport through relational cues such as psychological safety and warmth, whereas higher-ranking individuals prioritize task-relevant cues—competence, consistency, and strategic alignment—when forming trust [

20]. These differences may indicate that rapport is more closely associated with trust among those in subordinate positions.

Cultural dynamics further shape this relationship. In high power distance cultures such as South Korea, hierarchical structures often entail psychological distance and communication restraint, which may inhibit emotional exchanges from fostering trust, particularly among senior personnel [

22]. For example, Korean organizational culture has been shown to emphasize silence and deference in high-power relationships, reducing the likelihood that rapport is openly expressed or reciprocated [

18]. Even when rapport is felt, such norms may limit its internalization as trust, especially for those in positions of authority.

Nevertheless, some scholars caution that position may not act as a deterministic moderator in this relationship. Given that both rapport and trust are perceptual and affective constructs, their association is susceptible to subjective interpretation and response biases, particularly in self-reported surveys [

77]. Therefore, while the role of position is theoretically grounded, it must be interpreted with an understanding of both cognitive and cultural variability.

Despite these caveats, a growing body of research in organizational behavior and cultural psychology supports the idea that status affects how social cues are perceived and interpreted, particularly in non-Western cultural contexts [

78]. Accordingly, this study examines whether the strength of the rapport–trust association differs by position.

H7. The positive relationship between rapport and trust will be stronger among lower-position employees than among higher-position employees.

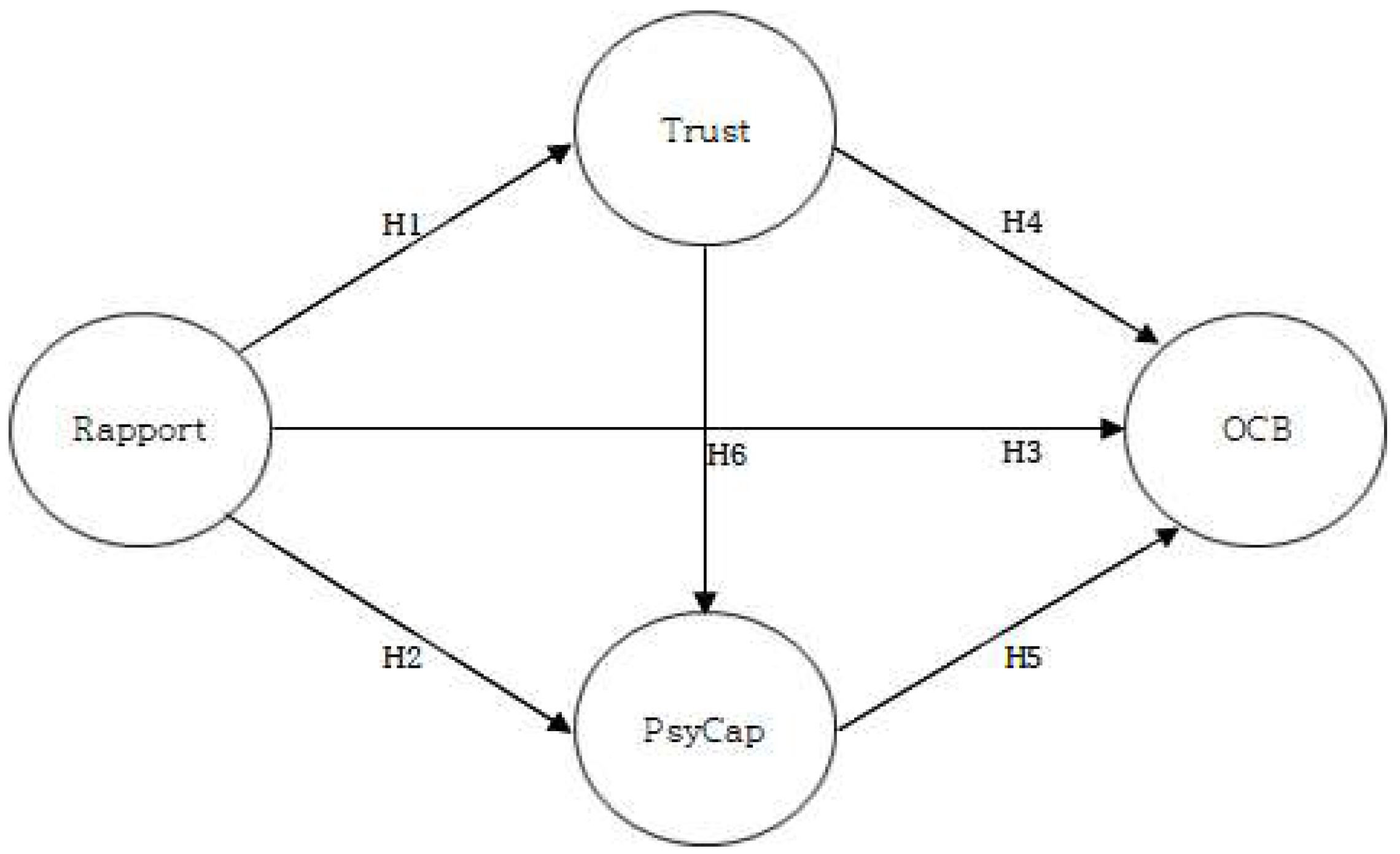

Based on this theoretical framework, the research model illustrated in

Figure 1 was developed. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test six hypotheses (H1–H6) concerning the causal and sequential mediation pathways among rapport, trust, PsyCap, and OCB. Additionally, to assess the moderating role of hierarchical position (H7) on the relationship between rapport and trust, a multigroup analysis was conducted by comparing path coefficients across different position levels, thereby examining the statistical significance of moderation effects.

5. Discussion

This study examined how rapport, trust, and PsyCap jointly shape OCB in a high-intensity emotional labor setting. The findings offer a deeper theoretical interpretation of how relational and psychological resources unfold into behavioral outcomes in service organizations.

First, the absence of a direct relationship between rapport and OCB contrasts with prior research that presumed an immediate link between relational warmth and prosocial behavior [

49,

88]. This suggests that rapport functions not as a direct behavioral trigger but as an early-stage relational resource that establishes emotional safety and interpersonal ease. Rather than activating behavior on its own, rapport provides the affective foundation upon which trust can be formed. This reframes rapport as a relational base rather than a behavioral antecedent, prompting a reinterpretation of earlier linear models of relational influence.

Second, the validated sequential pathway from rapport to trust and subsequently to PsyCap demonstrates that relational resources must be transformed into internal psychological resources before they can meaningfully influence behavior. Unlike studies that treated rapport or trust as immediate predictors of OCB [

12], the present findings extend the resource-gain perspective of the JD-R model [

17,

25]. Specifically, the study provides empirical clarity regarding which social resources and through what mechanisms they translate into psychological capacities that support citizenship behaviors.

Third, the significant effect of PsyCap on OCB highlights PsyCap’s role not merely as a predictor of performance and well-being [

7,

14] but as a key psychological mechanism through which relational experiences shape behavior. This finding aligns with perspectives suggesting that positive relational experiences cultivate PsyCap [

51] and deepens understanding of the psychological underpinnings of discretionary service behavior.

Fourth, the indirect effect of rapport is interpretable within the structural context of Korean airlines, characterized by high power distance and strict emotion regulation norms. Employees in higher-ranking positions tend to rely less on emotional cues and more on task competence and consistency when forming trust [

22]. Consequently, the strength of the rapport–trust pathway varies across hierarchical levels. This indicates that organizational culture and power structures meaningfully shape how relational resources are converted into psychological ones.

Finally, this study clarifies the intersection between the JD-R framework and SET. JD-R outlines the structural logic of resource accumulation, whereas SET explains how interpersonal experiences become internalized as cognitive assurance [

19,

20]. Integrating these perspectives yields a coherent resource-transition sequence in which affective resources (rapport) develop into cognitive resources (trust), which then contribute to PsyCap, culminating in behavior (OCB). This multi-layered pathway enhances understanding of how sustainable OCB emerges—OCB that supports long-term service quality, team functioning, and organizational resilience [

1,

89].

Taken together, the findings establish rapport as a foundational relational resource that initiates the development of psychological and behavioral resources in service organizations. This offers a refined theoretical explanation of how relational experiences are translated into OCB and contributes to understanding sustainable citizenship behavior in emotional labor environments.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, by empirically validating the sequential pathway from rapport to trust, PsyCap, and OCB, this study demonstrates that the influence of relational resources on behavior is not immediate but unfolds through a multi-stage psychological mechanism. This challenges prior assumptions of a direct rapport–behavior link [

10] and repositions OCB within a broader resource-based developmental process.

Second, the study advances theoretical integration between the JD-R model and Social Exchange Theory. While the JD-R framework emphasizes resource accumulation [

17,

24], it has been less explicit about how social resources convert into psychological ones. By showing that rapport leads to trust and subsequently to PsyCap, the study operationalizes the resource-conversion pathway and anchors it in SET’s principle of reciprocity [

19,

20]. This integration provides a more complete model of how resources evolve across relational, cognitive, and psychological domains.

Third, the study extends PsyCap research by identifying everyday relational interactions—rather than structural factors such as leadership [

64] or organizational support [

14]—as meaningful antecedents of PsyCap. This reinforces contemporary views of PsyCap as a state-like, developable psychological resource [

51] and highlights the relational foundations of psychological growth in service settings.

Fourth, the multi-group analysis demonstrates that organizational hierarchy moderates the conversion of relational resources. The stronger rapport–trust linkage among lower-ranking employees aligns with cultural and structural explanations of power distance [

22] and shows that relational cues are interpreted differently across hierarchical levels. This finding contributes to theory by illuminating how organizational culture shapes relational dynamics.

Fifth, the study reframes OCB as a component of organizational sustainability. Drawing on prior research showing that OCB supports long-term service quality, safety, and organizational resilience [

89], the resource-transition model presented here clarifies the psychological foundations of sustainable OCB. By identifying PsyCap as a key psychological resource enabling the persistence of citizenship behavior, the study strengthens theoretical understanding of how service organizations can maintain sustainability in emotionally demanding environments.

5.2. Practical Implications

First, the findings indicate that rapport is directly associated with trust and PsyCap. This suggests that managers should move beyond fostering interpersonal closeness and instead cultivate processes that are related to the development of relational resources into personal psychological assets. In other words, relational interactions should be recognized as critical pathways for supporting psychological resources, rather than as immediate behavioral triggers [

15,

29].

Second, trust’s positive relationship with both PsyCap and OCB underscores the importance of fairness and transparency in organizational culture and systems for establishing the essential foundation for sustainable behaviors. It highlights the need for strategies that prioritize long-term human resource sustainability over short-term performance [

30,

39].

Third, PsyCap emerges as a central mediator of behavioral outcomes, suggesting that organizations should view it not as a fixed trait but as a state-like resource that may be cultivated through relational and contextual resources [

7,

67]. This insight offers new directions for Human Resource Development research on psychological capital development and for OB research on multilevel mechanisms that link relationships, psychological resources, and behaviors.

Fourth, the multi-group findings also suggest that relational interventions may be particularly impactful for lower-ranking or junior staff. Managers should therefore tailor their support strategies based on employee rank or tenure, focusing more intensively on rapport-building and trust development for those with limited structural power or organizational influence [

76].

Finally, in addition to the airline industry, these implications are relevant to other service sectors characterized by emotionally charged labor demands, including the hospitality, tourism, healthcare, and education domains. Thus, this study offers academic and practical guidance for designing sustainable HRM strategies in service industries, demonstrating how relational resources are understood to be linked to psychological resources, ultimately being associated with sustainable organizational behaviors.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study empirically examined the relationships among rapport, trust, PsyCap, and OCB in airline cabin crews and derived theoretical and practical implications. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the sample was limited to a specific country (South Korea) and industry (airline services), which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Given the emotionally intense and hierarchical nature of the airline industry, future studies should explore similar service sectors (e.g., hospitality, healthcare, education) across diverse cultural contexts to enable broader comparative validation. Cultural factors such as collectivism, emotional restraint, and high-power distance may uniquely influence interpersonal rapport, trust-building, and psychological resource development in East Asian contexts. Hence, future research should explicitly account for these cultural dimensions.

Second, the cross-sectional design constrains the ability to identify causal relationships and temporal sequencing among the variables. Longitudinal or experimental designs are necessary to trace the dynamic unfolding of the rapport–trust–PsyCap–OCB pathway over time.

Third, reliance on self-reported data raises the risk of social desirability and common method bias. Subsequent studies should employ multisource data collection methods, including supervisor ratings, peer evaluations, behavioral observation, or objective performance data to enhance construct validity.

Fourth, although the JD-R model was used to theorize the resource conversion mechanism, the interaction effect between demands and resources, which the JD-R model fundamentally assumes, was not tested. High job demands (e.g., emotional labor or work stress) may moderate the impact of rapport or trust on psychological capital. Future research should incorporate such interaction terms into the structural model to capture the conditional nature of the resource effects.

Fifth, although demographic variables (e.g., age, tenure, position) were collected, they were not included as control variables in the model. Future studies should examine the extent to which individual differences moderate or confound the relationships among the core variables to enhance internal validity.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights by empirically identifying rapport as a foundational factor that fosters trust and enhances psychological resources, ultimately driving sustainable discretionary behaviors in service organizations.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the structural relationships among rapport, trust, PsyCap, and OCB, contributing to research on positive organizational psychology and sustainable human resource management. Focusing on working flight attendants—who operate in emotionally charged and hierarchical team environments—this study empirically validated the pathway through which relational resources are converted into personal resources and, subsequently, into discretionary organizational behaviors.

The main finding is that rapport is indirectly associated with OCB through the sequential mediation of trust and PsyCap. This suggests that rapport serves less as an immediate behavioral driver and more as a relational foundation that fosters trust, which then enhances personal psychological resources. Consequently, OCB emerges from a multilayered and refined mechanism that extends beyond simplified models. Incorporating such moderating dynamics could further enrich the explanatory power of the model.

The study explains how relational resources (rapport and trust) are converted into personal resources (PsyCap), which foster OCB, a form of sustainable organizational behavior. This pathway not only enriches theoretical understandings but also offers practical insights into how relational capital can enhance human resource and social sustainability. These findings may be extended beyond the airline context to other service industries characterized by emotionally charged work, such as hospitality, tourism, healthcare, and education, providing valuable guidelines for designing sustainable Human Resource Management strategies.