How Warm Glow and Altruistic Values Drive Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Meal-Kit Brands

Abstract

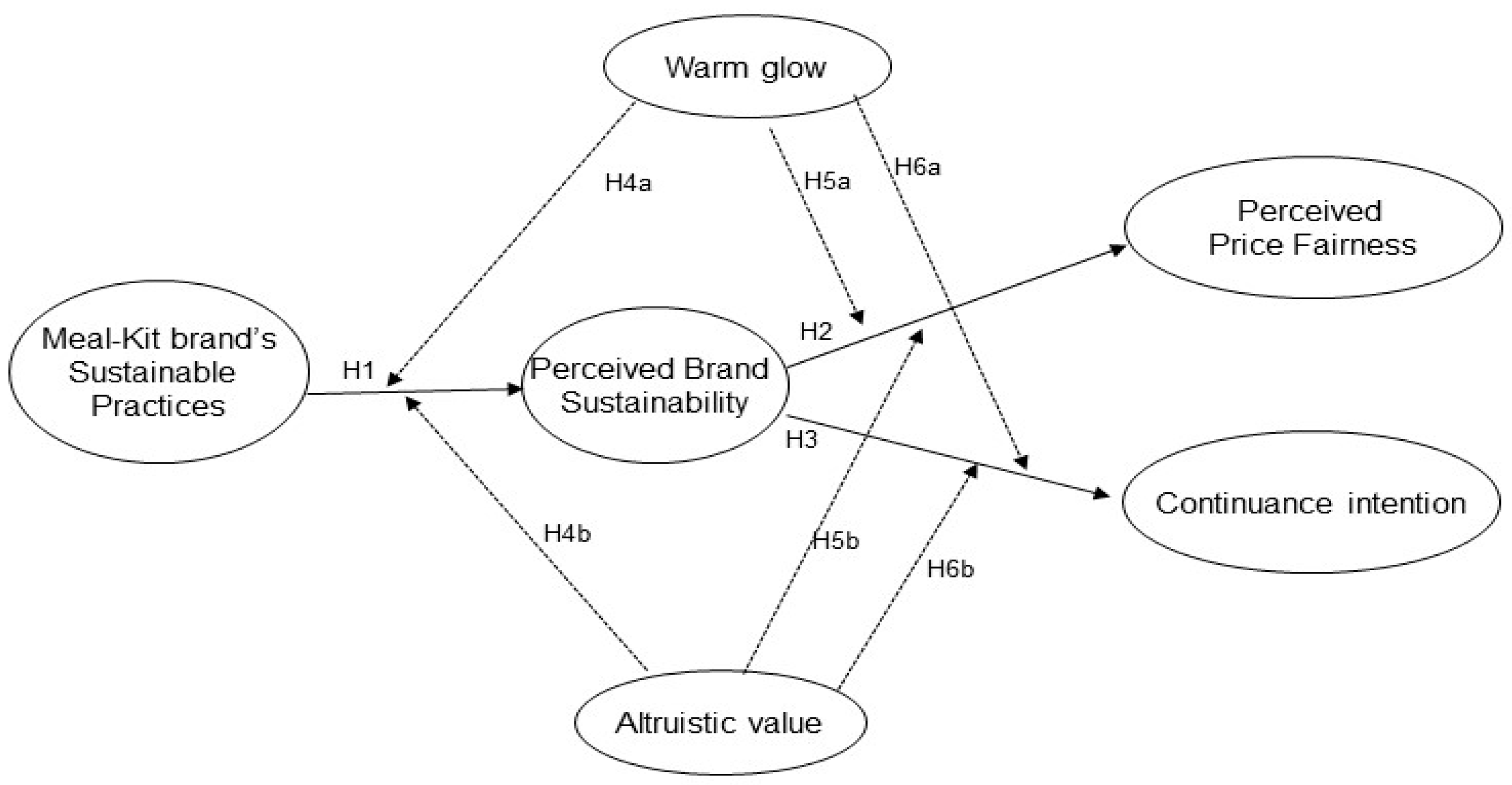

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Meal-Kit Brands’ Sustainable Practices and Perceived Brand Sustainability

2.2. Moderating Role of Warm Glow and Altruistic Value in the Relationship Between Sustainable Practices and Perceived Brand Sustainability

2.3. Moderating Role of Warm Glow and Altruistic Value in the Relationship Between Perceived Brand Sustainability and Perceive Price Fairness

2.4. Moderating Role of Warm Glow and Altruistic Value in the Relationship Between Perceived Brand Sustainability and Continuance Intention

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection, Measurement and Analysis

3.2. Sample Profile

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Assessments

4.2. Analysis of Main Effects

4.3. Assessment of Moderation Hypotheses

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Facts and Figures about Materials, Waste and Recycling. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Khan, S.A.; Sowards, S.K. It’s Not Just Dinner: Meal Delivery Kits as Food Media for Food Citizens. Front. Commun. 2018, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, J. Sunbasket Review: Healthy, Sustainable Meal Delivery. EcoWatch, 16 December 2020. Available online: https://www.ecowatch.com/sunbasket-reviews-2649520242.html (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Fenton, K.L. Unpacking the Sustainability of Meal Kit Delivery: A Comparative Analysis of Energy Use, Carbon Emissions, and Related Costs for Meal Kit Services and Grocery Stores. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, K. The Truth About Meal-Kit Freezer Packs. Mother Jones, 4 June 2017. Available online: https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2017/06/meal-kit-freezer-packs-blue-apron-hello-fresh/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Jia, L.; Linden, S. Green but not altruistic: Warm-glow predicts conservation behavior. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Econ. J. 1990, 100, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaraa, D.A.; Mahrous, A.A.; Elsharnouby, M.H. How manipulating incentives and participation in green programs affect satisfaction: The mediating role of warm glow. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebelhausen, M.; Chun, H.H.; Cronin, J.J.; Hult, G.T.M. Adjusting the warm-glow thermostat: How incentivizing participation in voluntary green programs moderates their impact on service satisfaction. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Shi, K.; Xu, S.; Wu, A. Will tourists’ pro-environmental behavior influence their well-being? An examination from the perspective of warm glow theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1453–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Hustvedt, G. Building trust between consumers and corporations: The role of consumer perceptions of transparency and social responsibility. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2014, 32, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Bijmolt, T.H.; Tribó, J.A.; Verhoef, P.C. Generating global brand equity through corporate social responsibility to key stakeholders. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Chang, C.C.A. Double standard: The role of environmental consciousness in green product usage. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.C. Perceptions of price unfairness: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Kledal, P.R.; Sulitang, T. Organic food consumers’ trade-offs between local or imported, conventional or organic products: A qualitative study in Shanghai. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Ng, A. Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S. Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, D.Z.; Ridgway, N.M.; Basil, M.D. Guilt and giving: A process model of empathy and efficacy. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Cho, S.B.; Kim, W. Consequences of psychological benefits of using eco-friendly services in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, T. Perceived green psychological benefits and customer pro-environment behavior in the value-belief-norm theory: The moderating role of perceived green CSR. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmentally significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Pure Altruism or Warm-Glow Altruism? Altruistic Motivation and Gender Differences in Socially Responsible Investment. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means–end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Relationships among green image, consumer attitudes, desire, and customer citizenship behavior in the airline industry. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. Internalized values as motivators of altruism. In Development and Maintenance of Prosocial Behavior; Staub, E., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 229–255. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, P.; Burke, P.F.; Devinney, T.M.; Louviere, J.J. What will consumers pay for social product features? J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 42, 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L. The malleable self: The role of self-expression in persuasion. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Lee, H.Y. Coffee shop consumers’ emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chieng, M.H. Building consumer–brand relationship: A cross-cultural experiential view. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 927–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, E. How self-identity and social identity grow environmentally sustainable restaurants’ brand communities via social rewards. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 516–532. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Eisend, M.; Apaolaza, V.; D’Souza, C. Warm glow vs. altruistic values: How important is intrinsic emotional reward in pro-environmental behavior? J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Guo, R. The effect of a green brand story on perceived brand authenticity and brand trust: The role of narrative rhetoric. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, E.; Baloglu, S.; Tanford, S. Building loyalty through reward programs: The influence of perceptions of brand attachment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Lacy, T. The warm glow effect and sustainability: Emotional drivers of consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for green products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2019, 29, 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Habel, J.; Schons, L.M.; Alavi, S.; Wieseke, J. Warm Glow or Extra Charge? The Ambivalent Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Activities on Customers’ Perceived Price Fairness. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, D.; Taylor, S., Jr. Nutrition and nature: Means-End Theory in crafting sustainable and health-conscious meal kit experiences. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweala, S.; Spiller, A.; Meyerding, S.G.H. Buy good, feel good? The influence of the warm glow of giving on the evaluation of food items with ethical claims in the UK and Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 207 | 65.3 |

| Female | 110 | 34.7 | |

| Age | 20–24 | 52 | 16.4 |

| 25–34 | 166 | 52.4 | |

| 35–44 | 63 | 19.9 | |

| 45–54 | 32 | 10.1 | |

| 55–64 | 3 | 0.9 | |

| 65 and above | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian, non-Hispanic | 276 | 87.1 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 25 | 7.9 | |

| African American | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Asian | 7 | 2.2 | |

| Other (specify below) | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Marital status | Married | 282 | 89.0 |

| Never Married | 33 | 10.4 | |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Education | High school diploma or below | 44 | 13.9 |

| Some college | 5 | 1.6 | |

| 2-year college | 14 | 4.4 | |

| 4-year college | 176 | 55.5 | |

| Post graduate | 16 | 5.0 | |

| Professional degree | 61 | 19.2 | |

| Others (specify) | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Occupation | Technical/Administrator | 58 | 34.7 |

| Sales/Service | 68 | 25.7 | |

| Professional | 77 | 24.3 | |

| Managerial | 95 | 12.4 | |

| Operator/Fabricator/Laborer | 7 | 2.0 | |

| Homemaker | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Student | 7 | 2.2 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.9 | |

| Annual household income | Less than $50,000 | 24 | 7.6 |

| $50,000~$74,999 | 108 | 34.1 | |

| $75,000~$99,999 | 151 | 47.6 | |

| $100,000~$149,999 | 25 | 7.9 | |

| Over $150,000 | 9 | 2.8 | |

| Total | 317 | 100 |

| Factor Loading | Eigen Value | Variance (%) | Cronbach’α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Practices | The shipping box is readily recyclable. | 0.787 | 2.661 | 29.567 | 0.826 |

| The meal-kit brand uses packaging and containers made from recyclable materials. | 0.828 | ||||

| The meal-kit brand implements a rewards program to promote green behavior, such as discounts for using reusable bags. | 0.764 | ||||

| Brand Sustainability | The meal-kit brand takes an interest in and pays attention to matters that affect the general public, such as social or environmental issues. | 0.821 | 1.540 | 17.109 | 0.795 |

| Meal-kit brand assumes social responsibility. | 0.708 | ||||

| Price Fairness | The meal-kit brand justifies higher prices. | 0.738 | 1.496 | 16.627 | 0.715 |

| A higher price for the meal-kit brand is fair. | 0.849 | ||||

| Continuance Intent | In the future, I would continue to use the meal-kit brand. | 0.786 | 1.394 | 15.491 | 0.728 |

| I will use the meal-kit brand next time with pleasure. | 0.844 | ||||

| Total variance(%) | 78.794 | ||||

| KMO | 0.914 | ||||

| Bartlett test | 1410.026 (36) sig 0.000 (<0.001) |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t-Value | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||||

| H1 | Brand Sustainability | Sustainable Practices | 0.688 | 0.049 | 0.622 | 14.092 | <0.001 |

| R = 0.622, R2 = 0.387, Adjusted R2 = 0.385 F = 198.595 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| H2 | Price Fairness | Brand Sustainability | 0.588 | 0.044 | 0.598 | 13.243 | <0.001 |

| R = 0.598, R2 = 0.358, Adjusted R2 = 0.356 F = 175.385 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| H3 | Continuance Intention | Brand Sustainability | 0.588 | 0.043 | 0.610 | 13.671 | <0.001 |

| R = 0.610, R2 = 0.372, Adjusted R2 = 0.370 F = 186.890 p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Dependent Variable | Brand Sustainability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

| Sustainable Practices | 0.622 *** | 0.019 | 0.020 *** |

| Warm Glow | 0.483 *** | 0.532 *** | |

| Altruistic value | 0.359 *** | 0.328 *** | |

| Sustainable Practice × Warm Glow | 0.134 * | ||

| Sustainable Practice × Altruistic Value | 0.095 * | ||

| R2 | 0.387 | 0.622 | 0.629 |

| ΔR2 | 0.235 *** | 0.007 * | |

| F | 198.595 *** | 171.752 *** | 105.656 *** |

| Dependent Variable | Perceived Price Fairness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

| Brand Sustainability | 0.598 *** | 0.099 | 0.052 |

| Warm Glow | 0.296 *** | 0.271 *** | |

| Altruism | 0.369 *** | 0.367 *** | |

| Brand Sustainability × Warm Glow | 0.071 | ||

| Brand Sustainability × Altruistic Value | 0.053 | ||

| R2 | 0.358 | 0.512 | 0.521 |

| ΔR2 | 0.154 *** | 0.010 * | |

| F | 175.385 *** | 109.246 *** | 67.701 *** |

| Dependent Variable | Continuance Intent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

| Brand Sustainability | 0.610 *** | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| Warm Glow | 0.339 *** | 0.385 *** | |

| Altruism | 0.462 *** | 0.406 *** | |

| Brand Sustainability × Warm Glow | 0.151 * | ||

| Brand Sustainability × Altruistic Value | 0.192 * | ||

| R2 | 0.372 | 0.597 | 0.604 |

| ΔR2 | 0.225 *** | 0.007 * | |

| F | 186.890 *** | 154.575 *** | 94.901 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, Y.J. How Warm Glow and Altruistic Values Drive Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Meal-Kit Brands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198780

Jang YJ. How Warm Glow and Altruistic Values Drive Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Meal-Kit Brands. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198780

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Yoon Jung. 2025. "How Warm Glow and Altruistic Values Drive Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Meal-Kit Brands" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198780

APA StyleJang, Y. J. (2025). How Warm Glow and Altruistic Values Drive Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Meal-Kit Brands. Sustainability, 17(19), 8780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198780