Application of Long Short-Term Memory and XGBoost Model for Carbon Emission Reduction: Sustainable Travel Route Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contribution to Reducing Carbon Emissions

1.3. Sustainability Framework

1.4. Related Works

1.5. Paper Organization

2. Methods and Preliminaries

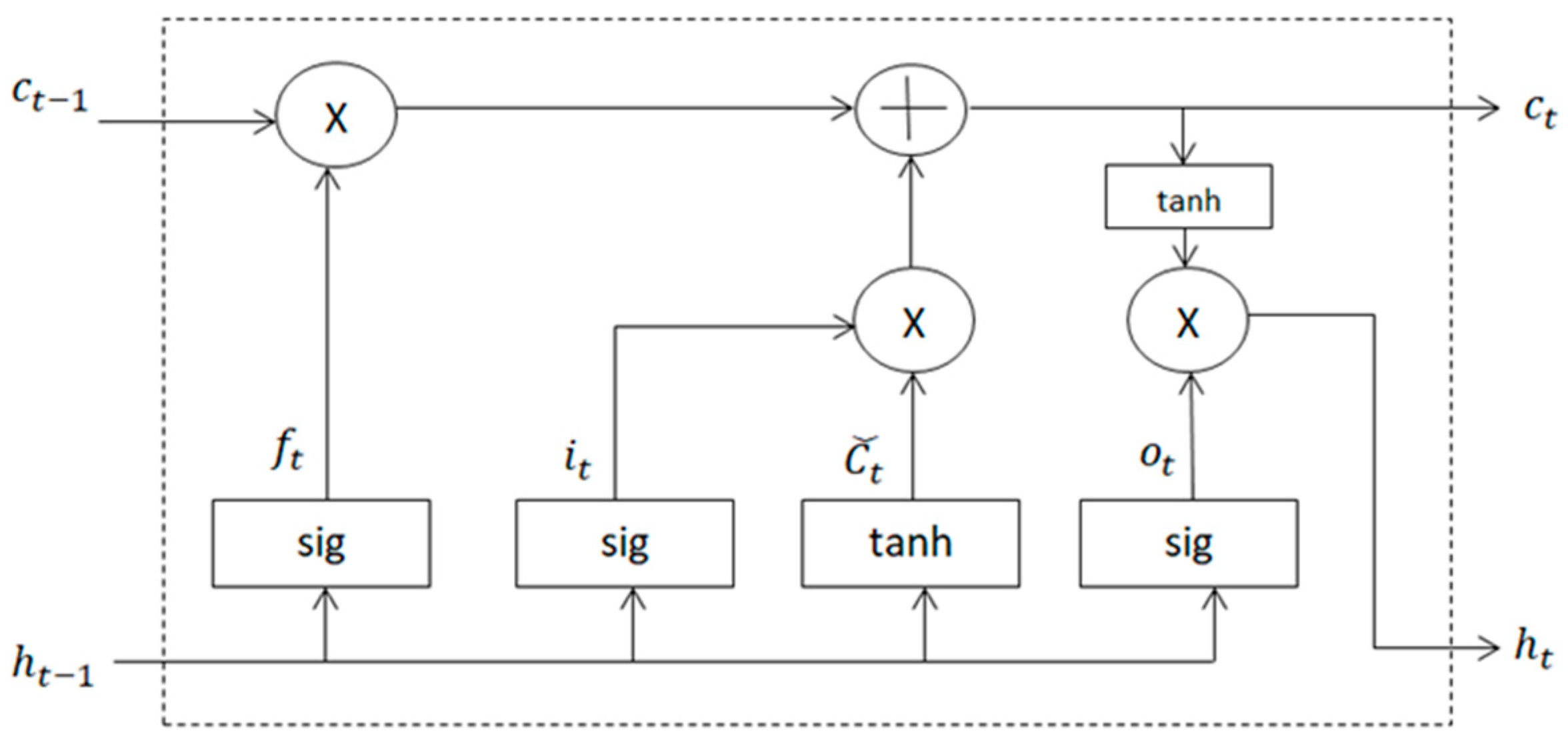

2.1. LSTM Model

2.2. XGBoost

2.3. Technical Infrastructure

2.4. Data Management and Integration

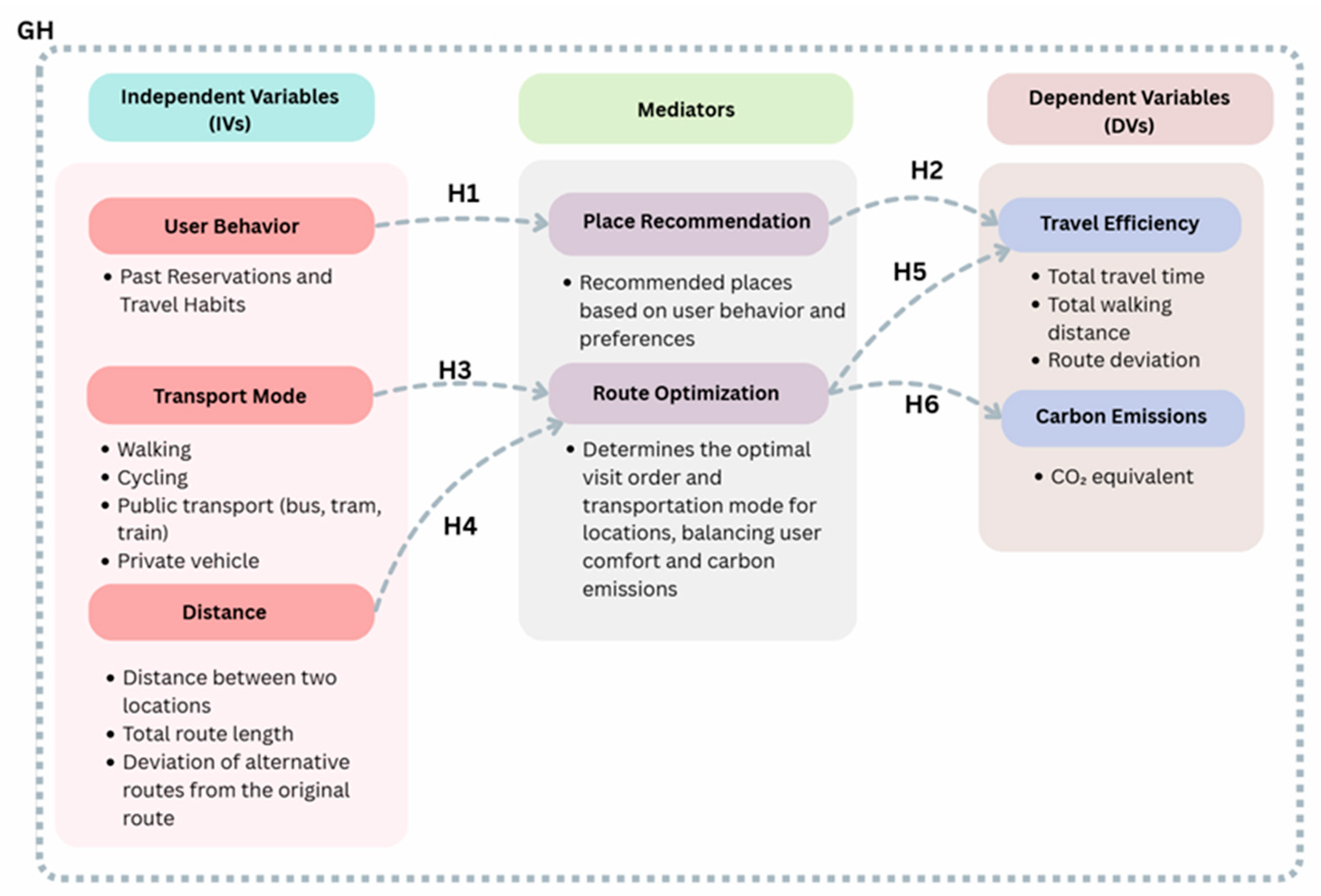

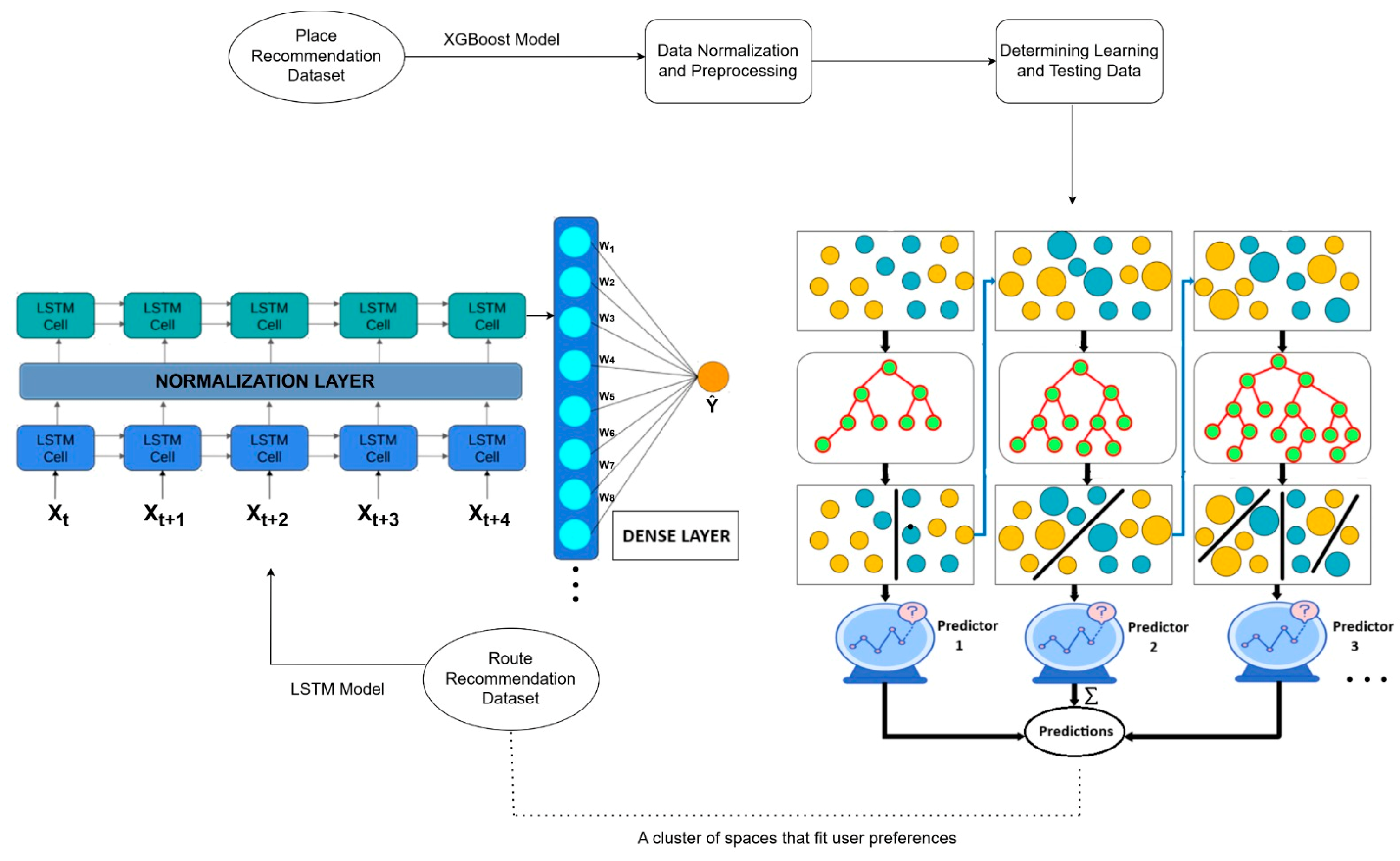

3. TRP Architecture

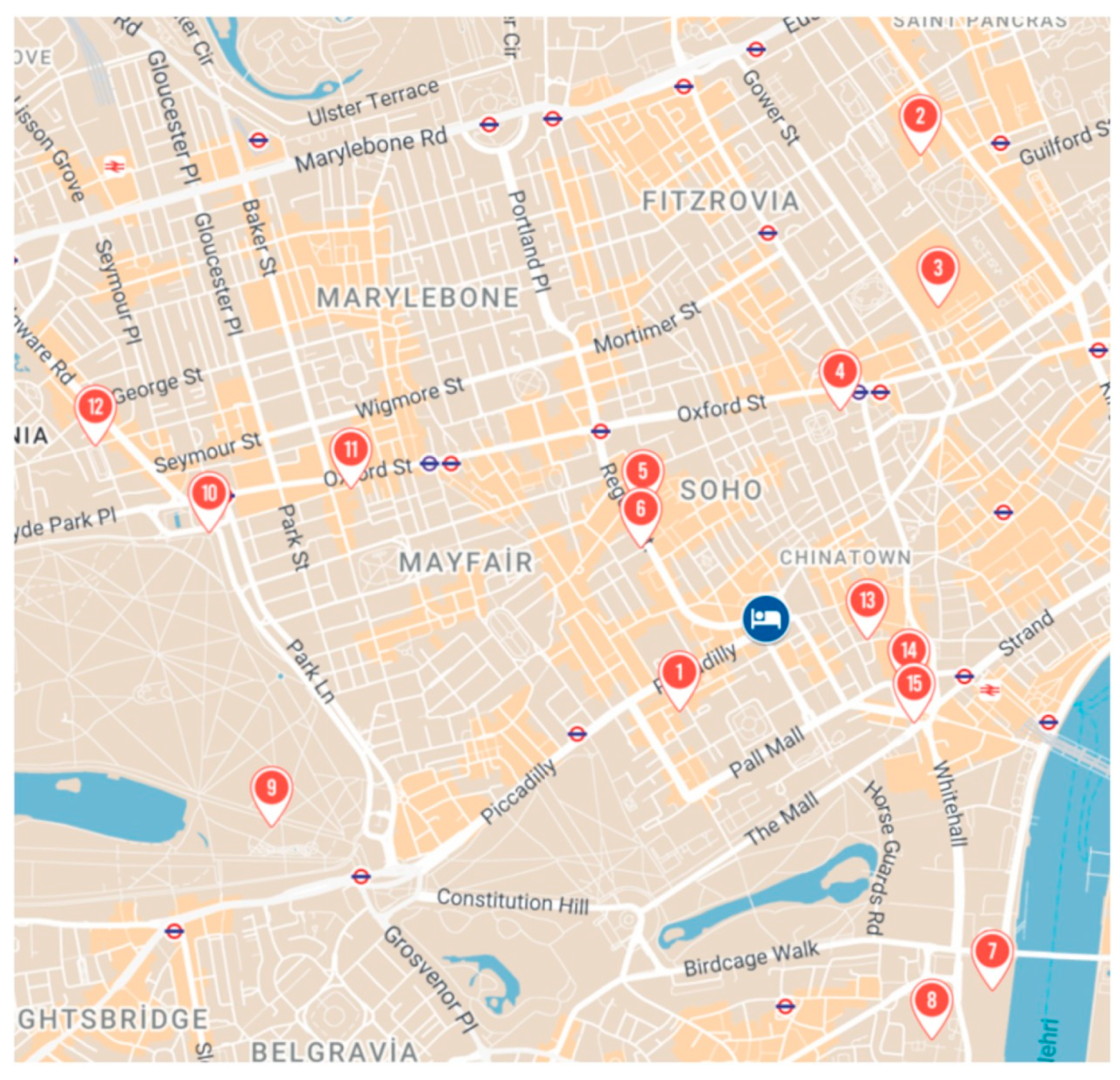

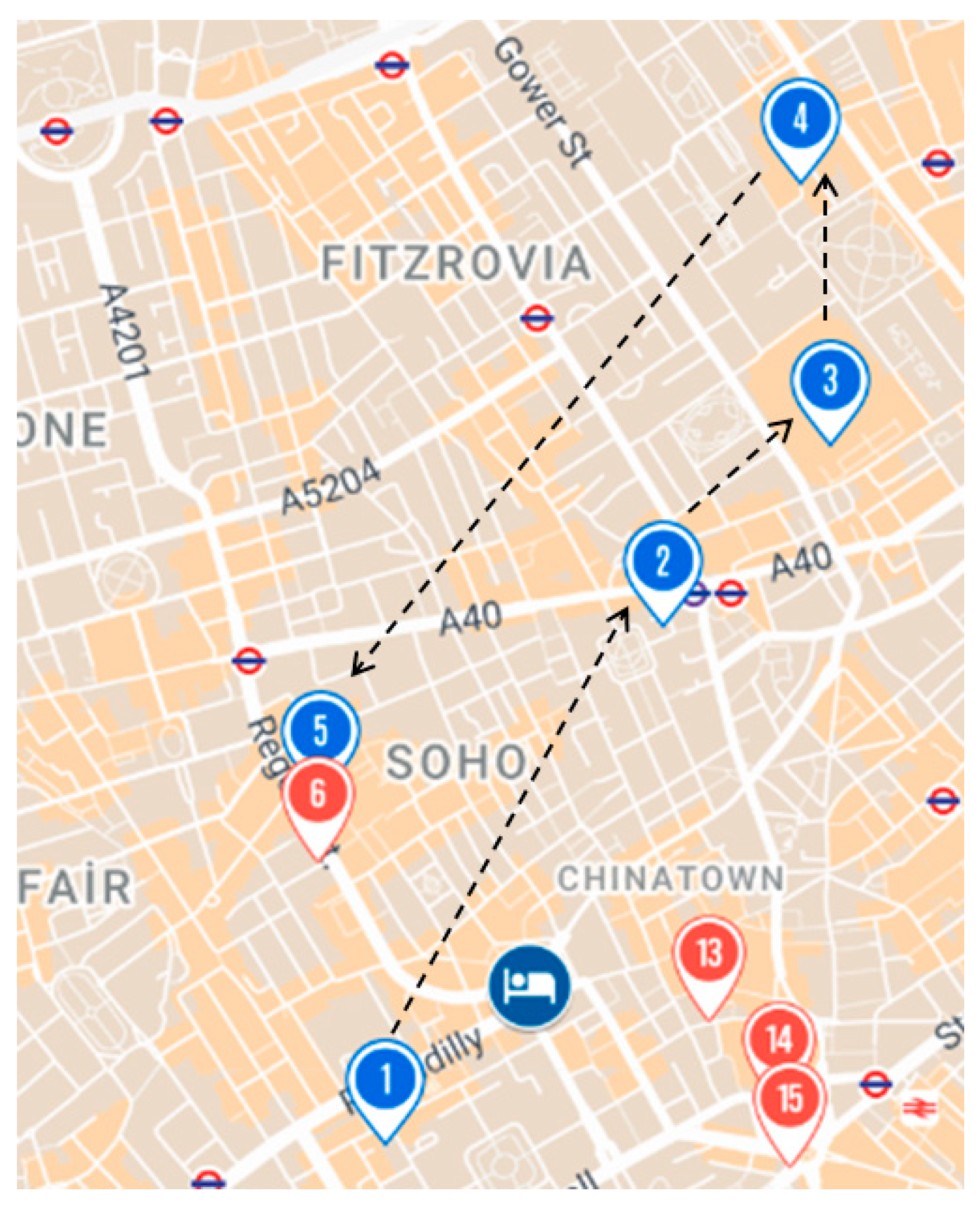

4. Implementation

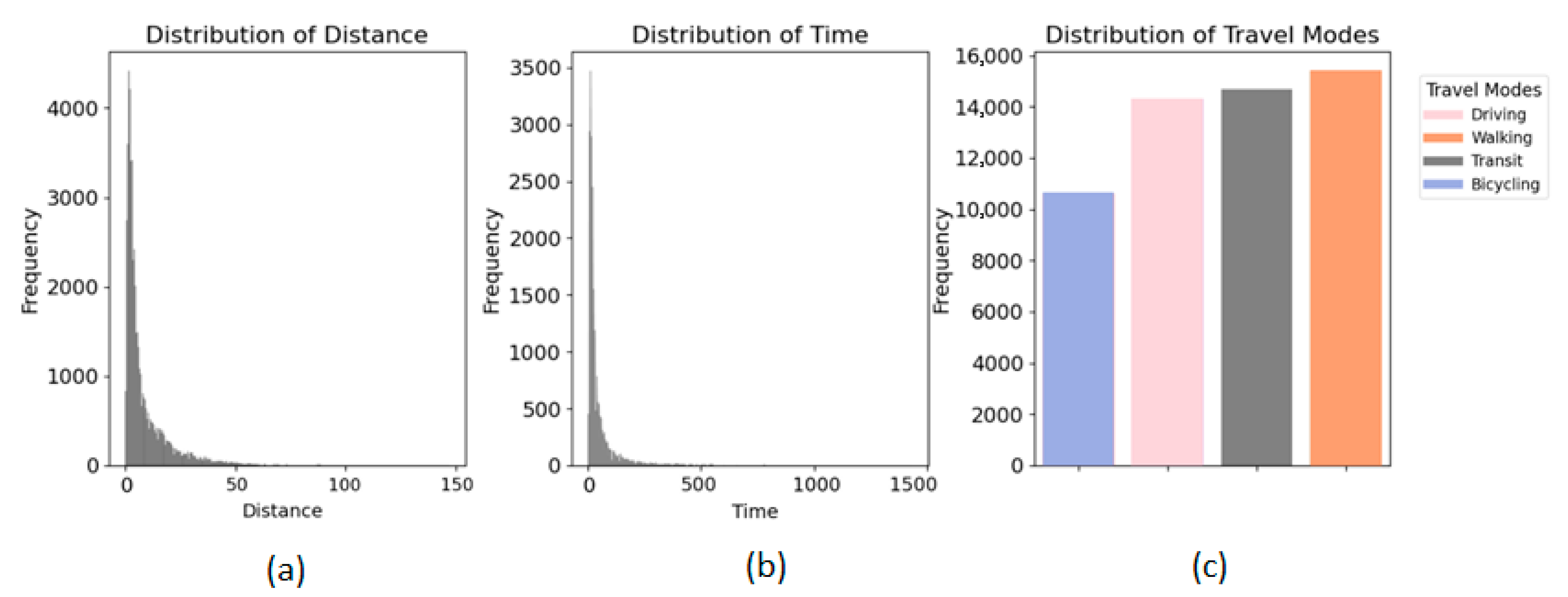

4.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

4.2. Data Transformations

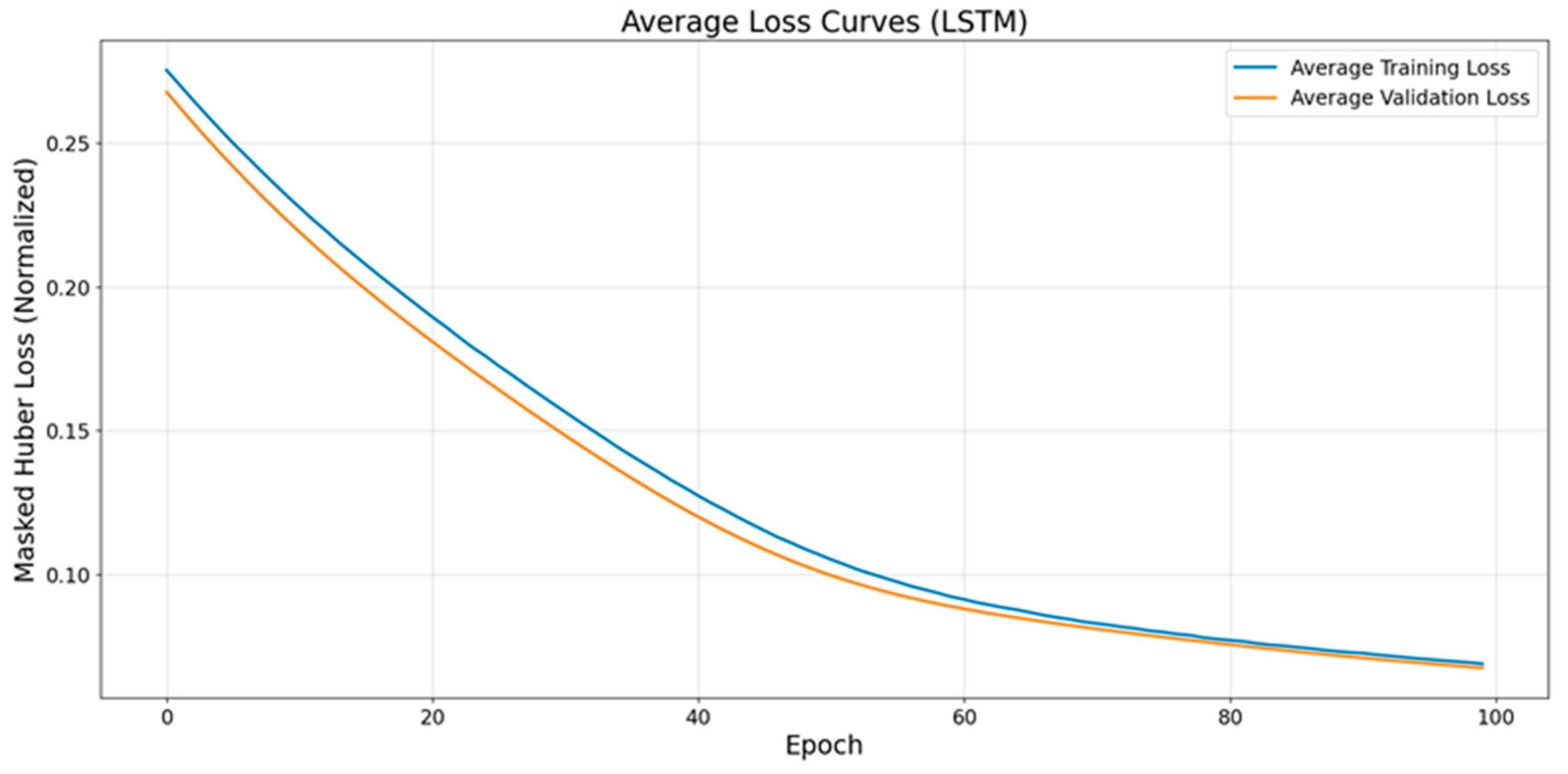

4.3. Route Data and LSTM Model Training

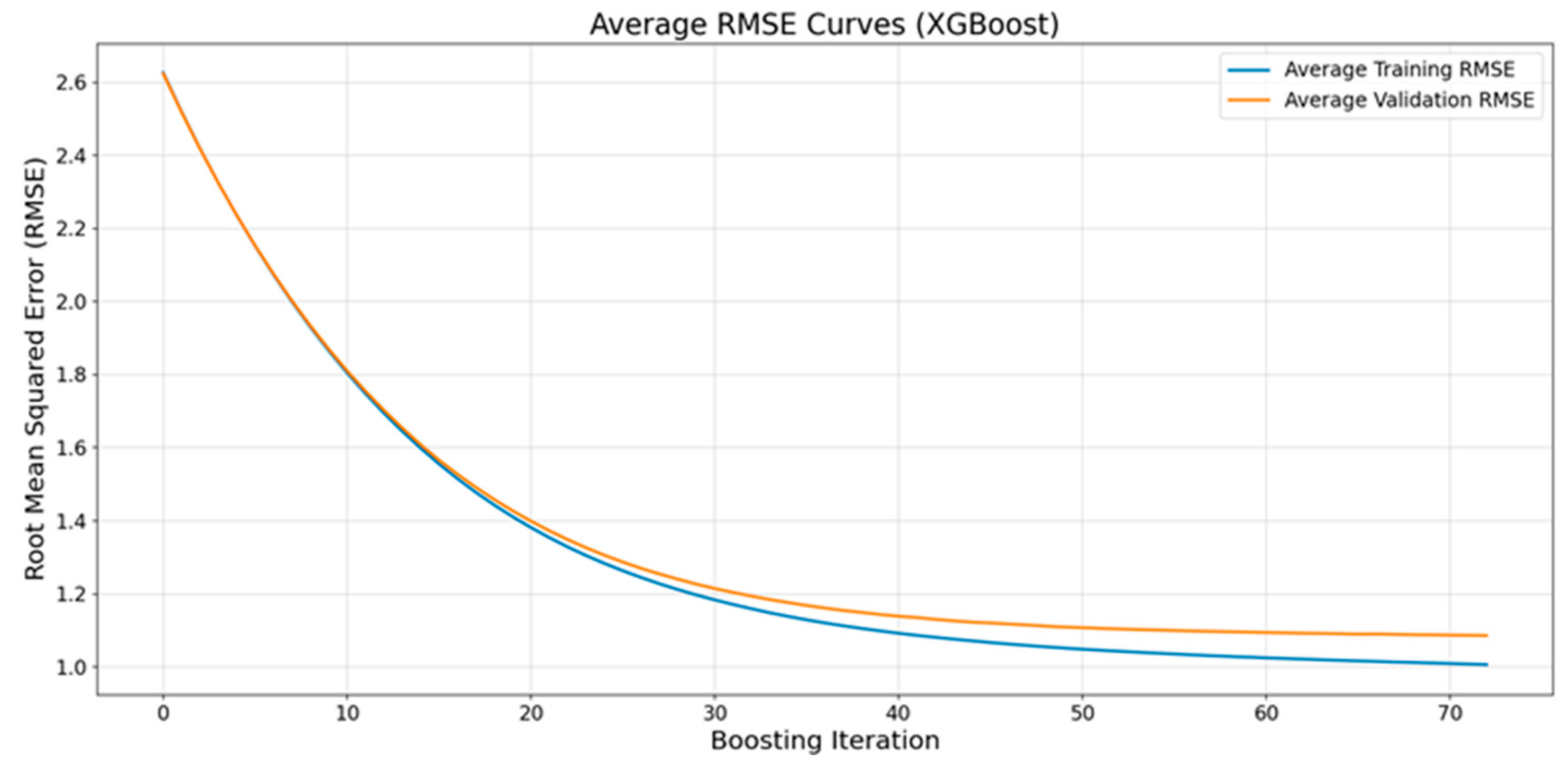

4.4. Proposed LSTM Model and XGBoost

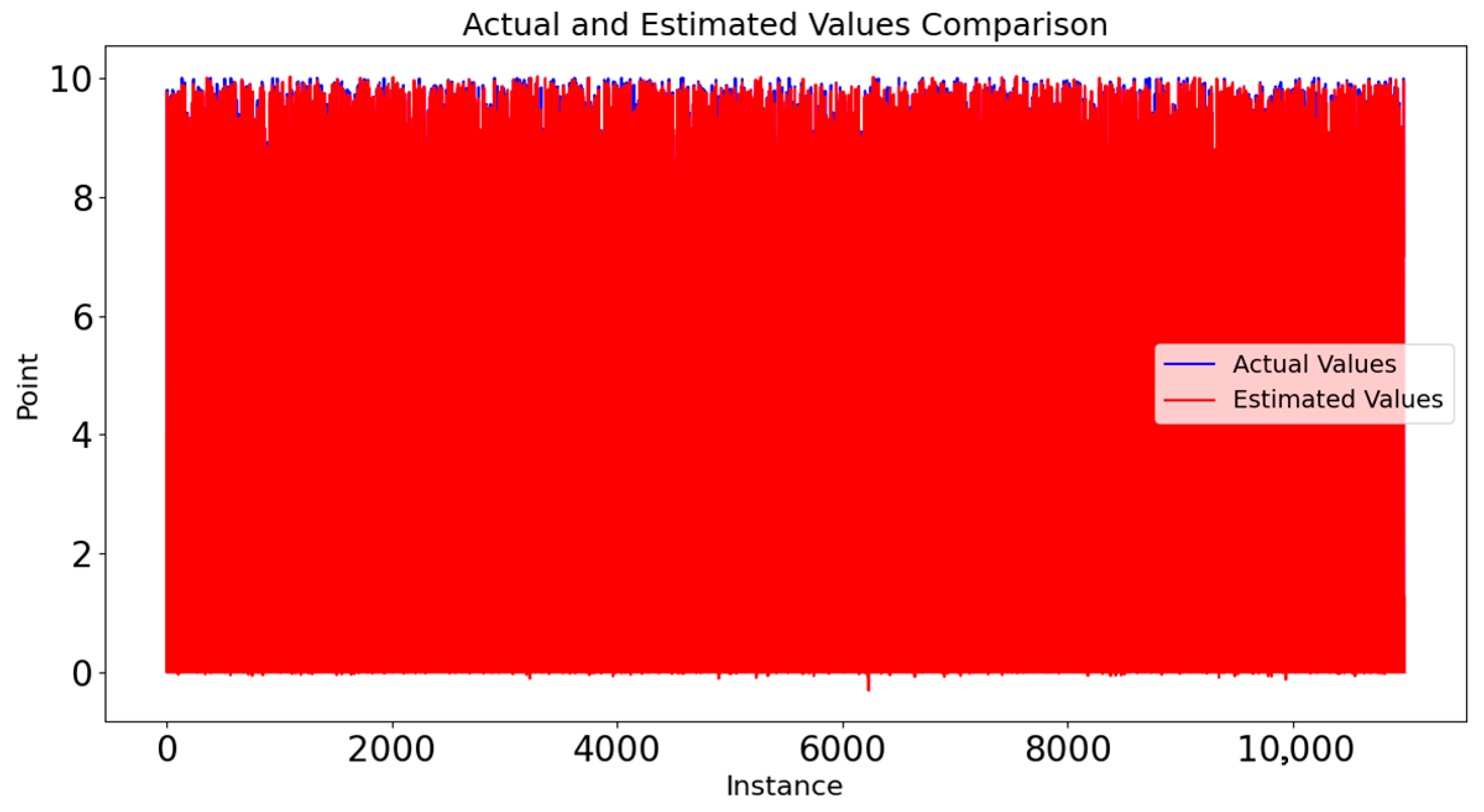

4.5. Comparison of Estimated and Actual Values

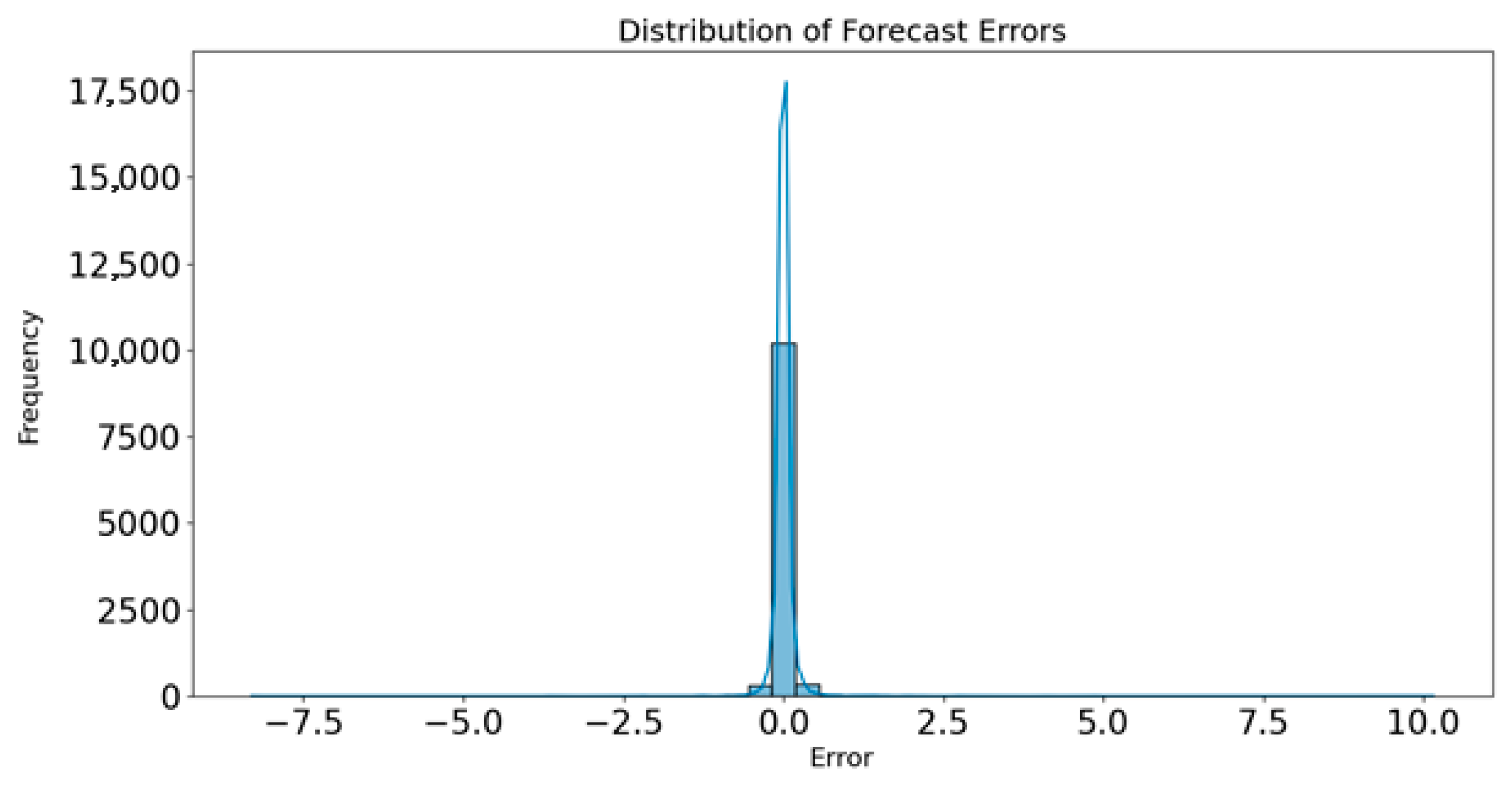

4.6. Distribution of Forecast Errors

4.7. Statistical Analysis

4.8. Distribution of Futures

5. Performance Metrics

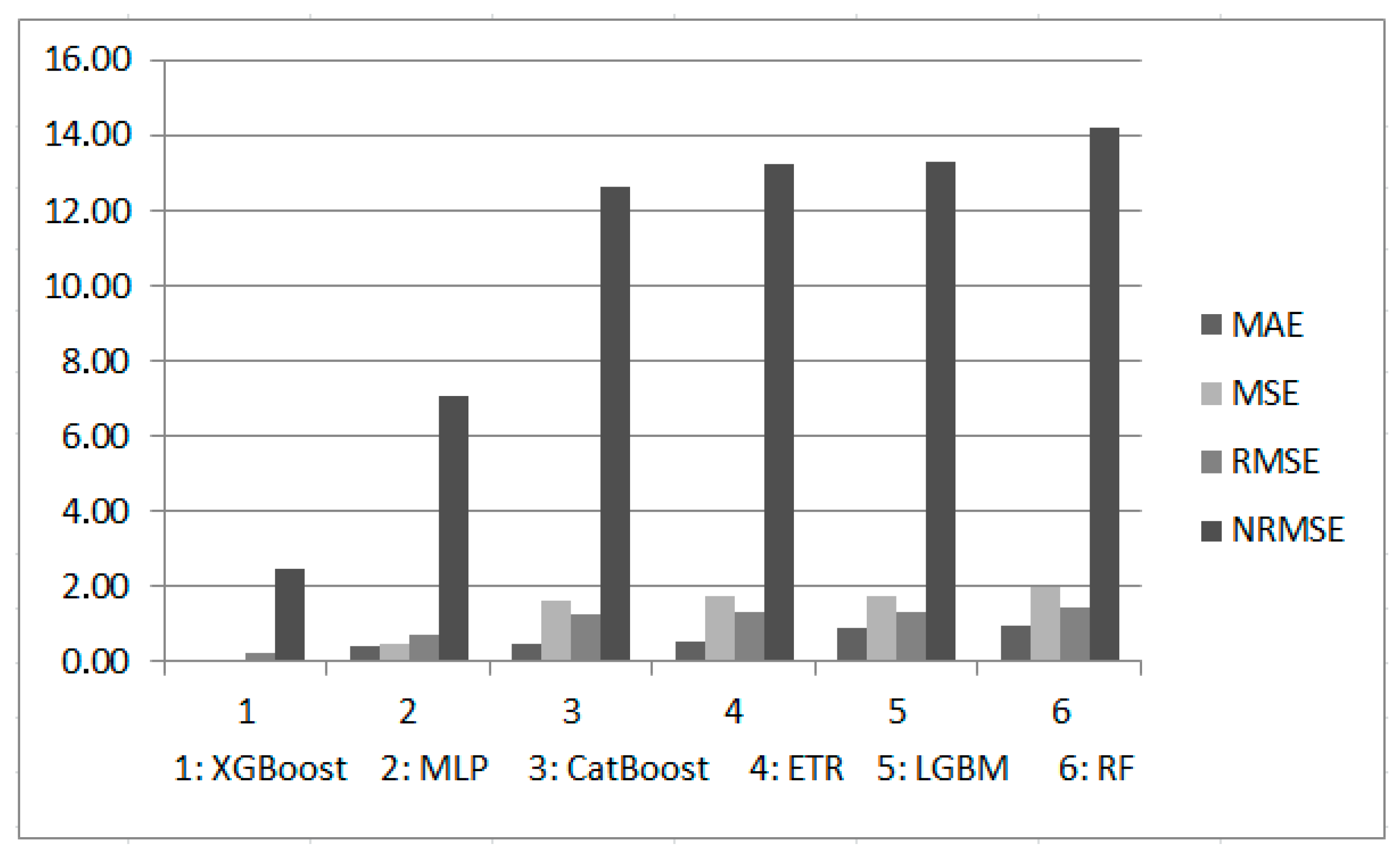

5.1. Comparison of XGBoost and Other Algorithms

- MLP is a type of artificial neural network consisting of input, hidden, and output layers that can learn nonlinear models. Activation functions are typically used in the hidden layers, while the output layer does not use them. MLPs are trained using the backpropagation method and work with loss functions such as mean squared error. They provide an effective solution for applications requiring multiple outputs [42,43].

- RF is a method used in classification and regression problems. It creates multiple decision trees and combines their results to make the final decision. At each split, random features are selected, which helps reduce variance. It can work with both categorical and continuous data and provides effective results even in cases of missing or corrupted data. Additionally, it can be successfully applied to complex datasets with many variables [42,44].

- ETR is an algorithm consisting of multiple decision trees that operates on the entire training data. The trees are constructed by selecting random subsets of features and split points. This approach increases generalization performance by ensuring independence and delivers successful results in both classification and regression problems [45].

- LightGBM is a histogram-based algorithm that can handle categorical features and provides fast training time with low resource usage. The decision trees are split based on leaf information, which leads to lower loss and better results compared to other algorithms in terms of accuracy. Moreover, it is an optimized algorithm that works effectively with large datasets [46].

- CatBoost is an algorithm which quickly processes categorical data by using the GBDT algorithm. It can achieve effective results even with limited data compared to deep learning models. This algorithm improves performance by working with categorical features during the training process, rather than during preprocessing as in traditional GBDT. Additionally, it uses special methods to prevent overfitting and prediction bias, improving prediction accuracy [47].

5.2. Comparison of LSTM and Other Algorithms

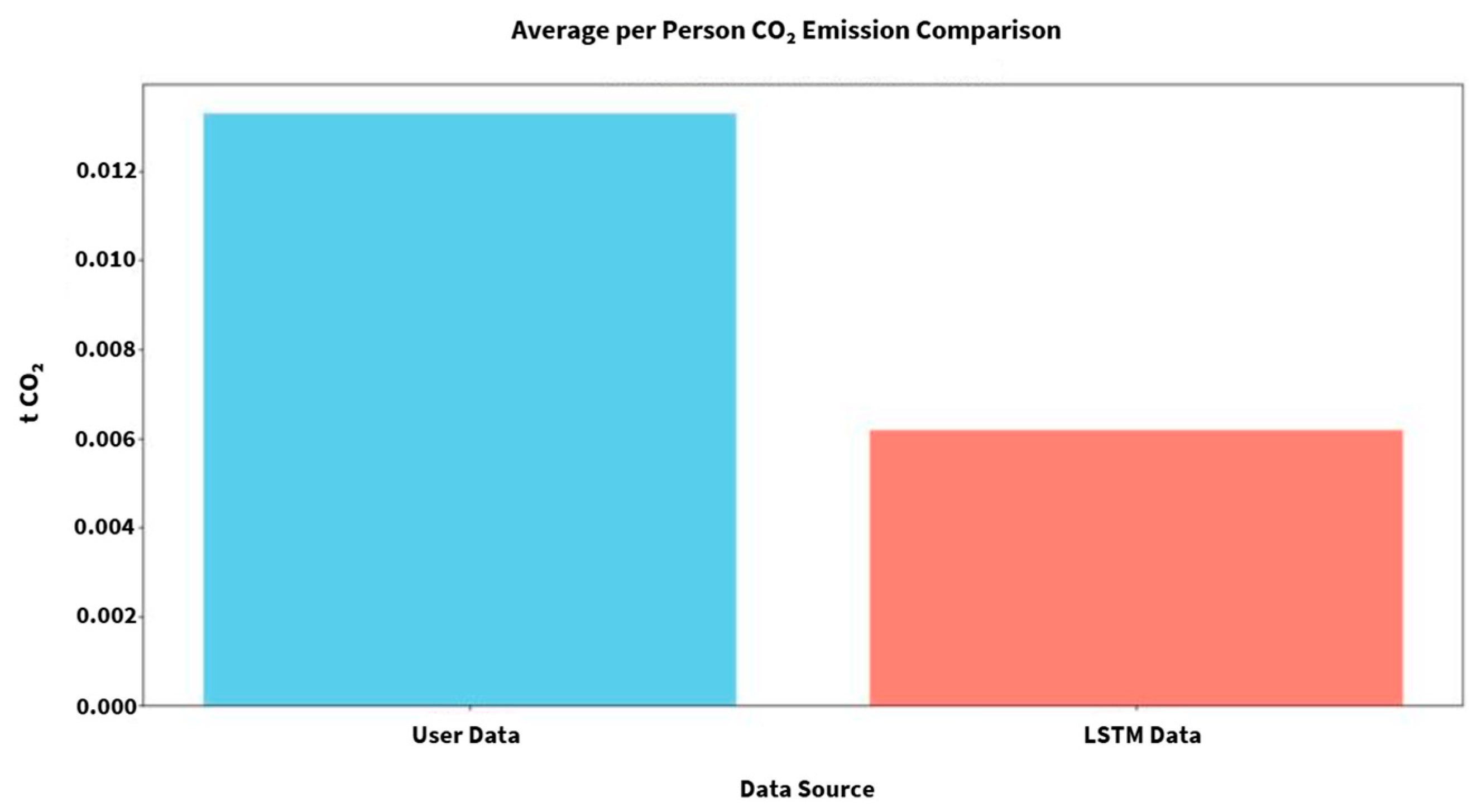

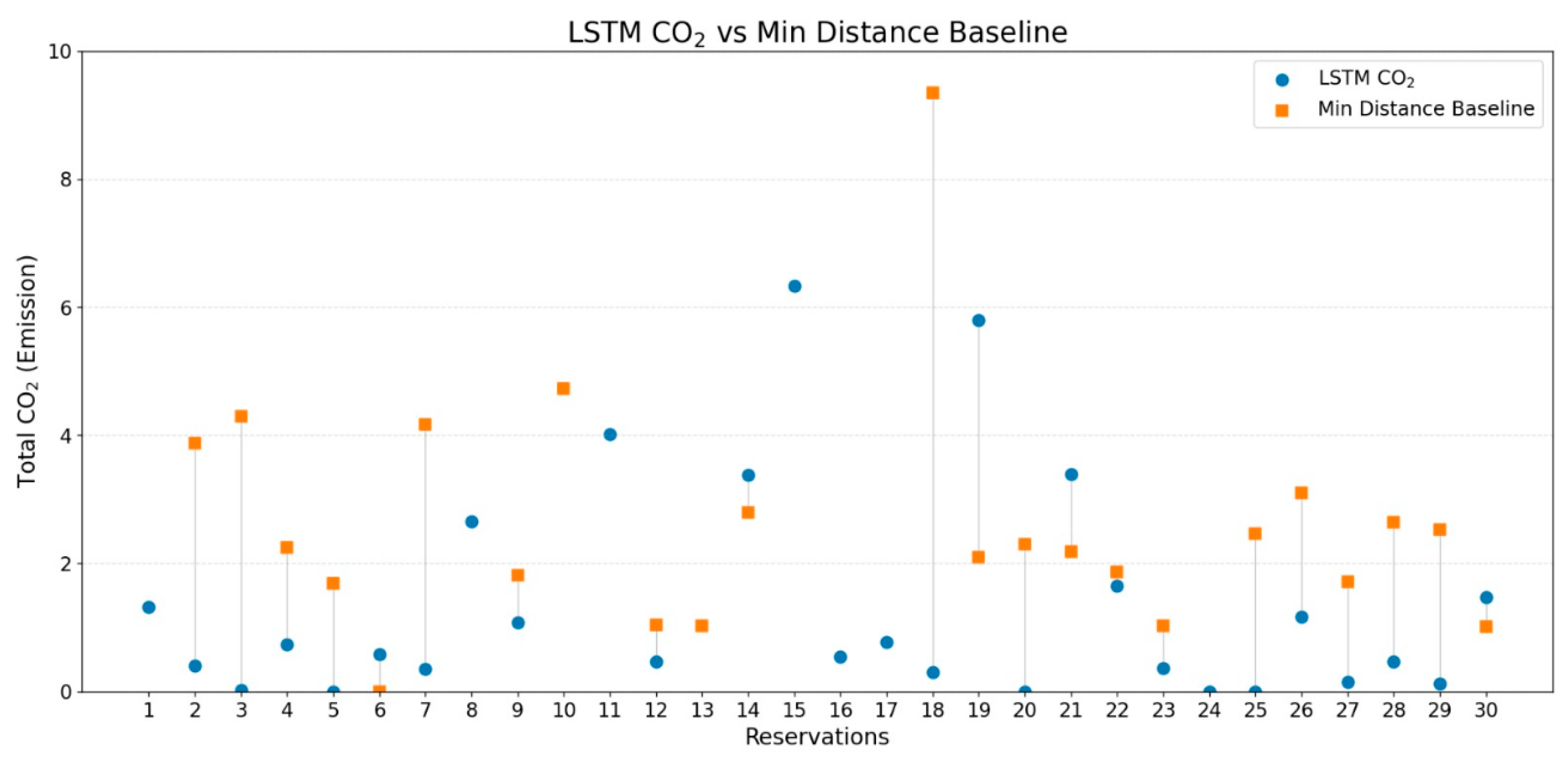

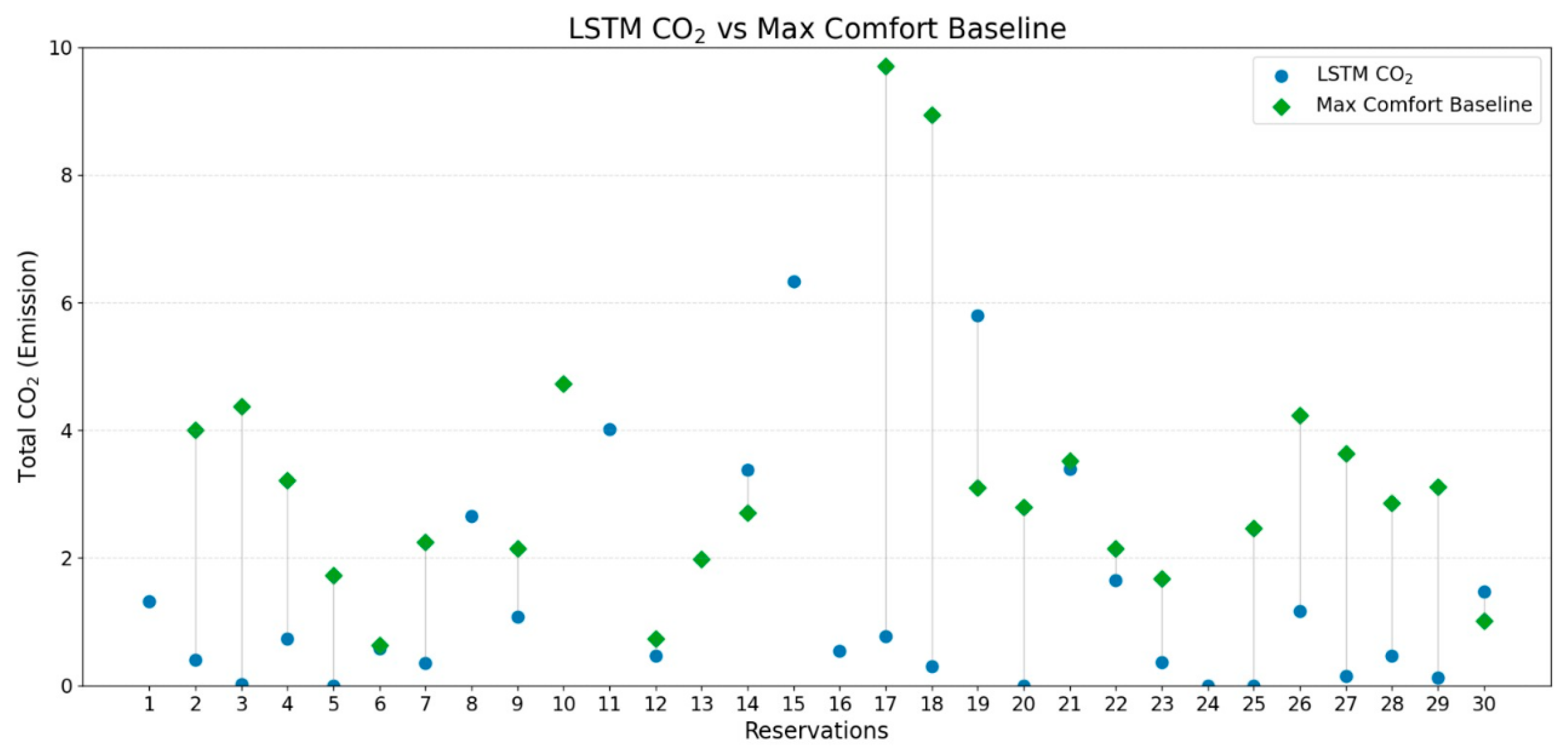

6. Impact of TRP on Carbon Emission

7. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| ETR | Extra Trees Regressor |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| Gg | Gigagram |

| GHGs | Greenhouse Gas emissions |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| GtCO2e | Gigatons of CO2 equivalent |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perception |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| TRP | Travel Route Planning |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Sadollah, A.; Nasir, M.; Geem, Z.W. Sustainability and Optimization: From Conceptual Fundamentals to Applications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouakkaz, A.; Mena, A.J.G.; Haddad, S.; Ferrari, M.L. Efficient Energy Scheduling Considering Cost Reduction and Energy Saving in Hybrid Energy System with Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylejmani, K.; Abdurrahmani, V.; Ahmeti, A.; Gashi, E. Solving the Tourist Trip Planning Problem with Attraction Patterns Using Meta-Heuristic Techniques. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2024, 26, 633–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.F.; Rodriquez, P.D. Tourism as a Challenge; WIT Series on Tourism Today; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aribas, E.; Daglarli, E. Transforming Personalized Travel Recommendations: Integrating Generative AI with Personality Models. Electronics 2024, 13, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Emissions Gap Report 2024: No More Hot Air … Please! With a Massive Gap between Rhetoric and Reality, Countries Draft New Climate Commitments; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/46404 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The Carbon Footprint of Global Tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization; International Transport Forum. Transport-Related CO2 Emissions of the Tourism Sector–Modelling Results; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, J.-P.; Daudens, F. Deploying a Cost-Effective and Production-Ready Deep News Recommender System in the Media Crisis Context. In Proceedings of the ORSUM@ACM RecSys 2020, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 25 September 2020. Virtual Event. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Developing Deep LSTM Model for Real-Time Path Planning in Unknown Environments. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Dependable Systems and Their Applications (DSA), Xi’an, China, 28–29 November 2020; pp. 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, F.; Peng, D.; Zhang, C.; Hong, B. Route Planning by Merging Local Edges into Domains with LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; pp. 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, P. Path Planning of a Mobile Robot for a Dynamic Indoor Environment Based on an SAC-LSTM Algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-W.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, J.-H. Path Planning for Multi-Arm Manipulators Using Soft Actor–Critic Algorithm with Position Prediction of Moving Obstacles via LSTM. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Deng, H.; Gong, J.; Chen, H. RNN-Based Default Logic for Route Planning in Urban Environments. Neurocomputing 2019, 338, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.-T.; Tong, V.; Tran, H.A.; Duong, C.S.; Nguyen, T.L.T. LSTM-Based Server and Route Selection in Distributed and Heterogeneous SDN Network. J. Comput. Sci. Cybern. 2023, 39, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanagavarapu, S.; Sridhar, S. SDPredictNet—A Topology-Based SDN Neural Routing Framework with Traffic Prediction Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 January 2021; pp. 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Azzouni, A.; Boutaba, R.; Pujolle, G. Neuroute: Predictive Dynamic Routing for Software-Defined Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Tokyo, Japan, 26–30 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Li, T. Optimizing Logistics in Forestry Supply Chains: A Vehicle Routing Problem Based on Carbon Emission Reduction. Forests 2025, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, B.M. AI-Driven Optimization of Urban Logistics in Smart Cities: Integrating Autonomous Vehicles and IoT for Efficient Delivery Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, C.; Zheng, S.; Ma, G.; Chen, Z. Multimodal Transportation Route Optimization of Emergency Supplies under Uncertain Conditions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, X. Optimum Route and Transport Mode Selection of Multimodal Transport with Time Window under Uncertain Conditions. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Bauer, P.H. Optimal Stochastic Eco-routing Solutions for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 3807–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owais, M.; Alshehri, A. Pareto Optimal Path Generation Algorithm in Stochastic Transportation Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 58970–58981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.; Owais, M. Reliable Vehicle Routing Problem Using Traffic Sensors Augmented Information. Sensors 2025, 25, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champahom, T.; Banyong, C.; Janhuaton, T.; Se, C.; Watcharamaisakul, F.; Ratanavaraha, V.; Jomnonkwao, S. Deep Learning vs. Gradient Boosting: Optimizing Transport Energy Forecasts in Thailand Through LSTM and XGBoost. Energies 2025, 18, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko, T.; Akindeji, K. Hybrid Forecasting for Energy Consumption in South Africa: LSTM and XGBoost Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınarer, G.; Yeşilyurt, M.K.; Ağbulut, Ü.; Yılbaşı, Z.; Kılıç, K. Application of various machine learning algorithms in view of predicting the CO2 emissions in the transportation sector. Sci. Technol. Energy Transit. 2024, 79, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Climate Change, October 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Singer, M. Climate Change and Social Inequality: The Health and Social Costs of Global Warming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 152, pp. 1–247. [Google Scholar]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Burke, M. Global Warming Has Increased Global Economic Inequality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9808–9813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Houdt, G.; Mosquera, C.; Nápoles, G. A Review on the Long Short-Term Memory Model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 5929–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaja, S.; Shakshuki, E.M.; Yasar, A. Long Short-Term Memory Approach for Routing Optimization in Cloud ACKnowledgement Scheme for Node Network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 184, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, B.; Müller, T.; Vietz, H.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. A Survey on Long Short-Term Memory Networks for Time Series Prediction. Procedia CIRP 2021, 99, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Tai, L.-Y.; Lo, C.-C. An LSTM-Based Personalized Travel Route Recommendation System. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, J.; Ahmed, U.; Amin, A.; Alharbi, T.; Alharbi, A.; Aziz, I.; Khan, A.R.; Mahmood, A. Electric Vehicle Charging Station Load Forecasting with an Integrated DeepBoost Approach. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 116, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H. Establishing a soil carbon flux monitoring system based on support vector machine and XGBoost. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, J. The Onion Architecture: Part 1. Jeffrey Palermo Blog 2008. Available online: https://jeffreypalermo.com/2008/07/the-onion-architecture-part-1/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Sun, H.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Y.; Cui, J.; Xing, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L. A Linear Interpolation and Curvature-Controlled Gradient Optimization Strategy Based on Adam. Algorithms 2024, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Chatterjee, M.; Kaur, G.; Vavilala, S. Deep Learning Applications for Disease Diagnosis. In Deep Learning for Medical Applications with Unique Data; Gupta, D., Kose, U., Khanna, A., Balas, V.E., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, N.; Ozturk, O.; Beken, M. Estimation of Gas Emission Values on Highways in Turkey with Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 10th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Istanbul, Turkey, 26–29 September 2021; pp. 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, M.; Yesilbudak, M.; Bayindir, R. Forecasting of Daily Total Horizontal Solar Radiation Using Grey Wolf Optimizer and Multilayer Perceptron Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Brasov, Romania, 3–6 November 2019; pp. 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Camana, M.R.; Garcia, C.E.; Hwang, T.; Koo, I. REM-Based Indoor Localization with an Extra-Trees Regressor. Electronics 2023, 12, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Huang, H.; Sun, G.; Li, Z.; Ouyang, C. Advancing Predictive Models: Unveiling LightGBM Machine Learning for Data Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computer, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICCBD+AI), Guiyang, China, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.S.; Dhanalakshmi, R. Performance Analysis of CatBoost Algorithm and XGBoost Algorithm for Prediction of CO2 Emission Rating. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 14–16 December 2023; pp. 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Ge, Q. State of Energy Estimation of Electric Vehicle Based on GRU-RNN. In Proceedings of the 2022 37th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Beijing, China, 19–20 November 2022; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, O.S.; Alshehri, O.M.; Samma, H. Blood Glucose Prediction Using RNN, LSTM, and GRU: A Comparative Study. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Systems and Emergent Technologies (IC_ASET), Hammamet, Tunisia, 27–29 April 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routray, N.; Rout, S.K.; Sahu, B. Breast Cancer Prediction Using Deep Learning Technique RNN and GRU. In Proceedings of the 2022 Second International Conference on Computer Science, Engineering and Applications (ICCSEA), Gunupur, India, 8 September 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Weidema, B.P. Comparison of the Requirements of the GHG Protocol Product Life Cycle Standard and the ISO 14040 Series; 2.-0 LCA Consultants: Aalborg, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, P.; Ranganathan, J.; World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard, Revised Edition; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hünerli, E.; Karaca Dolgun, G.; Ural, T.; Güllüce, H.; Karabacak, D. Calculation of Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University’s Carbon Footprint with IPCC Tier 1 Approach and DEFRA Method. Kırklareli Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kardeş Selimoğlu, S.; Poroy Arsoy, A.; Bora Kılınçarslan, T. Creating Assurance on Greenhouse Gas Statements According to the International Assurance Standard 3410 within the Context of Elements of Assurance Engagement. J. Account. Financ. 2022, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, E.; Önler, E. A Study on the Calculation of the Carbon Footprint of Public Transport in Çorlu District of Tekirdağ Province. Eur. J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 41, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Revised 1996 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Volume III: Reference Manual, Chapter 1: Energy; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kiliç, M.Y.; Dönmez, T.; Adalı, S. Change of Carbon Footprint Due to Fuel Consumption: Çanakkale Case Study. Gümüşhane Univ. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanseren, B.; Mercan, B.; Özdemir, B.; Kadıoğlu, H.H.; Sel, Ç. Carbon Footprint in Vehicle Routing and an Industrial Application. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2019, 11, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Indicators | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Carbon Emissions | CO2 emissions per person (Gg CO2) |

| Energy Efficiency | Change in total CO2 emissions before and after route optimization | |

| Economic | Time Efficiency | Changes in total travel time, transportation options |

| Social | Accessibility | Route optimization, time planning |

| Technological | Model Performance | Evaluation of LSTM and XGBoost models using RMSE, MAE, MSE, and NRMSE metrics |

| Data Integration | Incorporation of user interaction and Google API map |

| Training Component | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Cross-Validation | GroupKFold (N_SPLITS = 5) |

| Seed Ensemble | ENSEMBLE_SEEDS = [42, 43, 44, 45, 46] |

| Batch Size | 64 |

| Epochs | 100 |

| EarlyStopping | patience = 8, restore_best_weights = True |

| Learning Rate Scheduling | ReduceLROnPlateau (factor = 0.5, patience = 3, min_lr = 1 × 10−7) |

| Training Component | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Max Depth | 4 |

| Learning Rate | 0.05 |

| N Estimators (Boosting Rounds) | 500 |

| Early Stopping | early_stopping_rounds = 20 |

| L2 Regularization (reg_lambda) | 1.0 |

| Cross-Validation | GroupKFold (N_SPLITS = 10) |

| Seed/Random State | 42 |

| Training Component | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Embeddings | (e.g., TravelMode represented with 6 dimensions, with mask_zero = True) |

| Layer Normalization | Applied after feature fusion |

| LSTM Stack | Two layers (50 units + 50 units, return_sequences = True) |

| Dropout | 0.15 |

| L2 Regularization | λ = 1 × 10−4 |

| Output Layer | TimeDistributed(Dense(1)) |

| Loss Function | Masked Huber (δ = 0.5) |

| Optimizer | Adam (lr = 2 × 10−4, clipnorm = 1.0) |

| Route | Time (min.) | Distance (km) | Vehicle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Location | Second Location | |||

| 1 (Housing) | 2 | 17 | 2.6 | Bus |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.8 | Bicycle |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 0.6 | Bicycle |

| 4 | 5 | 3 | 0.8 | Bicycle |

| Route | Time (min.) | Distance (km) | Vehicle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Location | Second Location | |||

| 1 (Housing) | 2 | 13 | 1.4 | Bus |

| 2 | 3 | 11 | 1.2 | Bus |

| 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.5 | Walking |

| 4 | 5 | 11 | 2.8 | Bicycling |

| Model | Wilcoxon Tests | Bootstrap Confidence Interval | Effect Size Rank-Biserial r_rb |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM (RMSE) | W = 0.0000, p = 2.386 × 10−10 | Mean difference = 1.6305 95% CI = [1.4843, 1.7873] | −0.8701 |

| LSTM (MAE) | W = 0.0000, p = 2.386 × 10−10 | Mean difference = 1.6273 95% CI = [1.5086, 1.7523] | −0.8701 |

| XGBoost (RMSE) | W = 0.0000, p = 1.9531× 10−3 | Mean difference = 0.101084 95% CI = [0.060589, 0.146333] | −1.0000 |

| XGBoost (MAE) | W = 3.0000, p = 9.766 × 10−3 | Mean difference = 0.080994 95% CI = [0.040150, 0.119400] | −0.8909 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MSE | NRMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2.48 |

| RF | 1.42 | 0.95 | 2.02 | 14.21 |

| CatBoost | 1.27 | 0.50 | 1.61 | 12.67 |

| LightGBM | 1.33 | 0.89 | 1.77 | 13.29 |

| ETR | 1.32 | 0.54 | 1.75 | 13.22 |

| MLP | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 7.07 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MSE | NRMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2.42 |

| RNN | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 4.14 |

| GRU | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 3.13 |

| Fuel Type | Intensity (kg/L) | Conversion Factor (TJ/Gg) (Total CO2) | Carbon Emission Factors (tC/TJ) | Oxidation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | 0.820 | 43.33 | 20.2 | 0.99 |

| Substance | Molar Mass (g/mol) |

|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 12 |

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Emek, S.; Ildırar, G.; Gürbüzer, Y. Application of Long Short-Term Memory and XGBoost Model for Carbon Emission Reduction: Sustainable Travel Route Planning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310802

Emek S, Ildırar G, Gürbüzer Y. Application of Long Short-Term Memory and XGBoost Model for Carbon Emission Reduction: Sustainable Travel Route Planning. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310802

Chicago/Turabian StyleEmek, Sevcan, Gizem Ildırar, and Yeşim Gürbüzer. 2025. "Application of Long Short-Term Memory and XGBoost Model for Carbon Emission Reduction: Sustainable Travel Route Planning" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310802

APA StyleEmek, S., Ildırar, G., & Gürbüzer, Y. (2025). Application of Long Short-Term Memory and XGBoost Model for Carbon Emission Reduction: Sustainable Travel Route Planning. Sustainability, 17(23), 10802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310802