Scholarly investigations related to the relationship between geopolitical risk (GPR) and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance can be categorized into two streams. The first strand focuses directly on the impact of GPR on corporate ESG performance. This body of literature provides extensive empirical evidence, revealing that GPR can either hinder or motivate ESG engagement. However, these studies often overlook the heterogeneity of multinational enterprises, particularly in terms of their resource endowments, internationalization strategies, and institutional environments, and offer limited insight into the underlying mechanisms that shape this relationship. The second strand emphasizes the heterogeneity of MNEs, focusing on the different motivations and capabilities firms possess in pursuing ESG initiatives. This line of research provides an explanatory framework that distinguishes firm-specific and country-specific determinants of ESG performance. Nevertheless, empirical applications of this framework remain limited.

This study bridges these two strands of literature by integrating insights from both. Drawing on the FSA–CSA framework, we develop a comprehensive model that explains how geopolitical risk influences the ESG performance of MNEs, while accounting for firm characteristics and external environmental conditions.

2.1. The Impact of GPR on Corporate ESG

The concept of ESG was introduced by the United Nations in 2004 as a framework for evaluating corporate sustainability practices [

6], and was further reinforced by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. ESG includes a wide range of corporate practices aimed at environmental responsibility, social equity, and sound governance. These include efforts in emission reductions [

9], product and service innovation through eco-innovation [

10], and waste management [

11,

12]; social initiatives such as employee well-being [

13], occupational health and safety, training and development [

14], workforce diversity and promotion opportunities [

15], and community engagement [

16]; and governance strategies such as board diversity [

11], executive alignment with sustainability goals [

17], and climate risk disclosure [

18].

At the same time, geopolitical risk (GPR)–defined as the political, economic, and environmental threats emerging from conflicts, violence, power struggles, and international tensions—has been identified as a major disruptor of ESG progress [

19]. According to the Global Risks Report published by the World Economic Forum, GPR has surpassed environmental degradation to become the foremost global concern. In the context of multinational enterprises, GPR introduces operational uncertainty, supply chain vulnerability, and financial volatility-factors that can significantly reshape corporate ESG behavior.

Empirical studies present two opposing yet not mutually exclusive perspectives on how firms respond to GPR. On the one hand, GPR may deter ESG investments, as firms seek to minimize risk and conserve resources amid heightened uncertainty [

20]. On the other hand, GPR may stimulate ESG performance, as firms attempt to strengthen legitimacy, appease stakeholders, and hedge against reputational or regulatory fallout [

21].

Numerous empirical findings support the former argument. Clance et al. (2019) [

22], using a dataset of 17 developed countries from 1899 to 2013, found that geopolitical conflict increased the risk of economic recessions, which in turn discouraged long-term corporate investments. Amosh et al. (2024) [

23], analyzing panel data from 5082 MNEs between 2011 and 2020, found that terrorist incidents had a significant negative effect on ESG performance. Sabbaghi (2024) [

24] demonstrated that ESG-rated stocks in emerging markets were particularly vulnerable to GPR shocks, with slower market response compared to developed markets. Similarly, Basnet et al. (2022) [

25] showed that, during the Russia–Ukraine conflict, high-ESG firms were more likely to exit the Russian market. The average ESG score of firms that exited was 68.44, suggesting that geopolitical crises may force the withdrawal of more responsible firms, leading to a scenario of “bad money driving out good.”

Conversely, a growing body of research supports the view that MNEs may intensify ESG practices as a strategic response to geopolitical threats. Fiorillo et al. (2024) [

21] argued that well-structured ESG strategies can enhance firm legitimacy and mitigate reputational damage in volatile environments. Belcaid (2024) [

1], using a non-linear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model, found that ESG investment served as a risk-hedging mechanism in Morocco, with ESG-related performance improving during periods of elevated GPR. This is especially pertinent for MNEs operating in environmentally or socially sensitive sectors, where proactive ESG initiatives–such as adopting clean energy or promoting human rights–can contribute to geopolitical conflict de-escalation and foster better diplomatic relations between host and home countries.

Recent empirical evidence also highlights the financial and operational resilience of firms with high ESG performance during geopolitical crises. Tsang et al. (2023) [

7] examined the financial impact of three major Russia–Ukraine war events on the top 100 firms in the S&P 500 Index, finding that firms with strong ESG scores exhibited greater supply chain resilience and experienced smaller declines in stock returns, averaging a 5% drop during the event windows. Similarly, Fiorillo et al. (2024) [

21] found that high ESG performance firms in the U.S., Japan, and the U.K. were better able to weather stock price crashes during times of geopolitical stress.

Firm-level studies also suggest that ESG engagement tends to increase under high-GPR conditions. Chun et al. (2024) [

26], in a study of Korean conglomerates from 2011 to 2019, found that firms increased ESG activities during periods of geopolitical instability, particularly those investing more heavily in R&D and marketing. Reyad (2024) [

27] observed a similar trend among firms in Eastern European, while Kuai and Wang (2024) [

28] reported that Chinese MNEs improved ESG transparency during periods of political tension, thereby reducing information asymmetry and attracting socially responsible investors. These findings emphasize the dual role of ESG as both vulnerability and a strategic asset in political unstable environment. High-ESG firms may be more exposed to international scrutiny and stakeholder expectations, yet they also tend to benefit from greater investor confidence, enhanced legitimacy, and access to diversified financing [

29,

30].

Overall, while the empirical findings on the relationship between GPR and ESG performance in MNEs are rich and diverse, they also pose challenges for forming a unified understanding of how GPR influences corporate ESG outcomes.

2.2. Heterogeneity of Multinational Enterprise and ESG Investment Strategies

The theoretical foundation of ESG performance in MNEs is primarily grounded in stakeholder theory, institutional theory, and the resource-based view. These frameworks provide an explanatory basis for understanding both the motivations behind ESG investment and the mechanisms through which GPR influences ESG outcomes. Stakeholder theory posits that corporations are accountable not only to shareholders but to a broader range of stakeholders, including employees, local communities, regulators, and civil society. For MNEs, particularly those operating in diverse and often volatile host-country environments, ESG engagement becomes a strategic mechanism to secure support of these stakeholders. High ESG performance can mitigate internal and external conflicts, enhance corporate reputation and reduce operational risks [

31]. The resource-based view emphasizes the importance of intangible assets—such as brand reputation, relational capital, and trust—as sources of sustained competitive advantage. ESG performance contributes significantly to the development and protection of these strategic assets [

32]. Firms with strong ESG profiles are better positioned to build long-term relational advantages that are difficult for competitors to imitate. Meanwhile, institutional theory emphasizes the role of regulatory frameworks, normative pressures, and cultural expectations in shaping corporate behavior. ESG performance is therefore influenced by legal requirements, social norms, and international standards, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Moreover, MNEs are not only passive recipients of institutional pressures but also active agents, capable of diffusing ESG practices into host-country institutions. High-ESG performance firms may serve as role models, shaping the expectations and behaviors of local firms through demonstrated effects.

While these three theoretical perspectives provide a comprehensive foundation for the strategic significance of ESG performance, they often overlook the dimension of firm-level heterogeneity. Not all MNEs possess the same motivations, resources, or capabilities to pursue ESG objectives, especially under the influence of GPR. This heterogeneity becomes particularly pronounced among MNEs from emerging markets, such as China, where firms differ widely in ownership structure, strategic orientation, international experience, and position within the global value chain. For example, Chinese MNEs include state-owned enterprises, large private enterprises, suppliers embedded in the global value chain, and entrepreneurial firms pursuing expansion to access strategic assets. Some firms—often referred to as “natural global MNEs”—possess strong internal capabilities and international orientation from inception, while others are small and medium-sized enterprises focusing on niche markets.

Taxonomies developed within international business literature help conceptualize these differences. OLI paradigm typology divides multinational corporations into resource-seeking, market-seeking, efficiency-seeking, and strategic asset-seeking types based on their investment motivations [

33]. Mathews (2006) [

34] introduced the Linkage–Leverage–Learning (LLL) paradigm to explain the behavior of emerging market MNEs, which often lack traditional ownership advantages and seek to compensate through internationalization. From this view, many Chinese MNEs engage in internationalization, not to exploit, but to build capabilities [

35]. Evidence includes Geely’s acquisition of Volvo and Lenovo’s acquisition of IBM’s PC division. Another influential framework is provided by Rugman and Verbeke (2011) [

36], who classify MNEs according to the interplay between firm-specific advantages (FSAs) and country-specific advantages (CSAs). Their typology includes four categories: high FSA–high CSA, high FSA–low CSA, low FSA–high CSA, and low FSA–low CSA firms.

Despite the richness of these theoretical models, ESG-related research has not fully integrated these taxonomies into empirical analyses of GPR effects. There remains a significant gap in understanding of how MNE heterogeneity influences ESG behavior under geopolitical uncertainty.

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Theoretical systems such as stakeholder theory, institutional theory (Ghoul et al., 2017) [

37], and the resource-based view provide systematic explanations for the necessity of ESG strategy (

Figure 1). These frameworks emphasize several reasons for the importance of ESG performance, including but not limited to the following: (1) ESG performance is closely related to the risks faced by MNEs in host countries. MNEs with high ESG performance are more likely to build mutually beneficial relationships with their stakeholders, enhancing their legitimacy (Ellili and Daoud, 2022) [

38]. On the other hand, moderate ESG performance can lead to ongoing tensions with local stakeholders, posing long-term operational risks in host countries. (2) ESG disclosure can reduce information asymmetry between investors and firms (Amir and Serafeim, 2018) [

39]. MNEs with high ESG performance may face fewer financing constraints as they are more attractive to investors. (3) Good ESG performance is associated with higher productivity, stronger competitive advantage, and improved financial performance (Eduardo and Caracuel, 2021; Ferraz et al., 2016) [

14,

40]. In such firms, stakeholders often share common values, which foster a unified strategic vision and greater motivation for sustainable development. As such, ESG investment can be seen as a strategic tool for achieving long-term, stable growth in host countries.

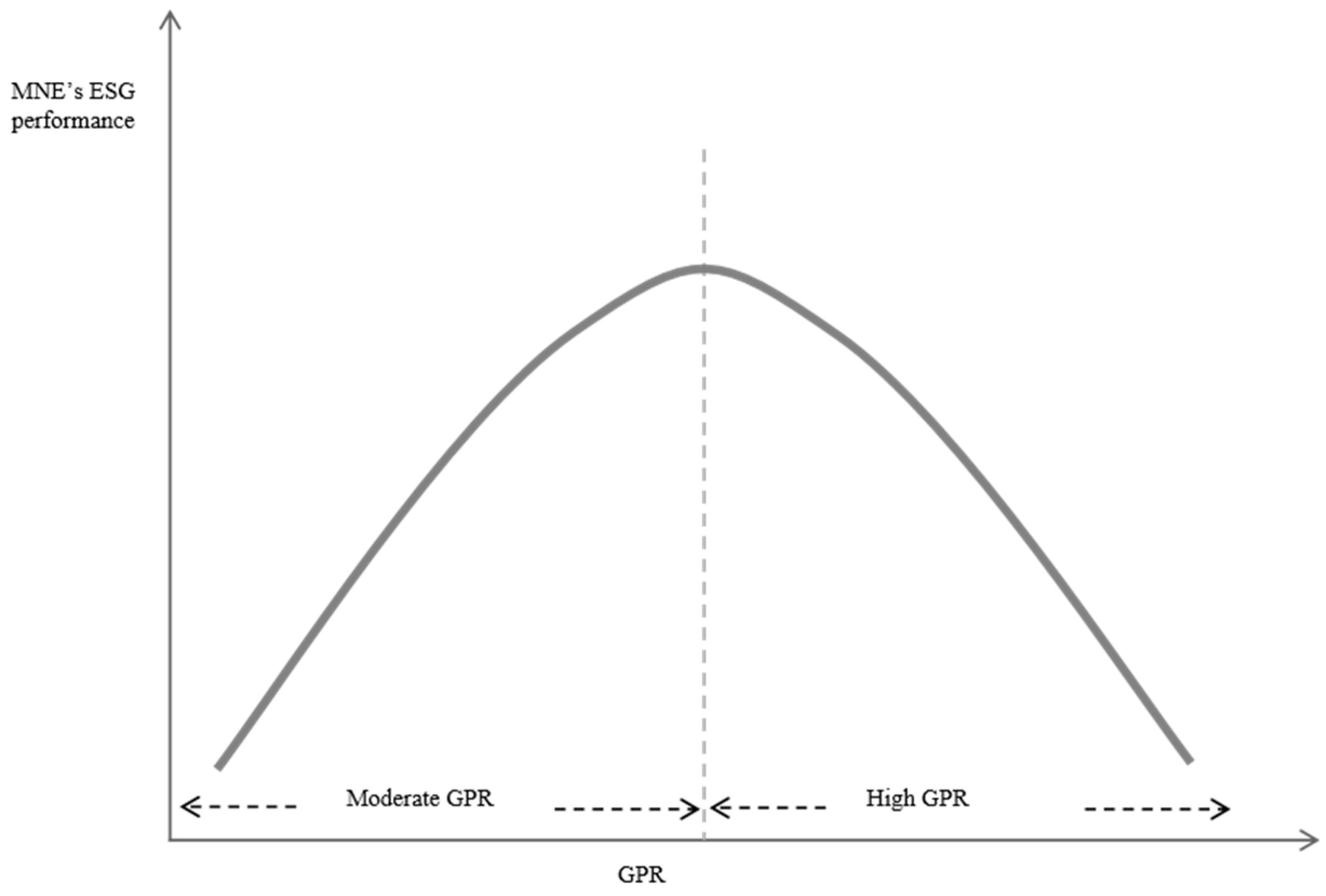

However, GPR can introduce significant uncertainty for MNEs [

2,

41], thereby influencing ESG decision-making. It is important to emphasize that the level of GPR can determine the extent of its impact. International events reflect GPR range from political reform and diplomatic negotiations to military confrontations and non-traditional large-scale violence. Under moderate-level GPR, MNEs may face increased pressure from the host country to demonstrate legitimacy. In response, firms may improve their ESG performance to mitigate investment risks—for example, by improving labor standards, reducing carbon emissions, or enhancing community engagement. In such scenarios, GPR and the ESG performance are positively correlated.

However, in cases of high-level GPR—such as armed conflict, violent protests, or military standoffs between home and host countries—this strategy may no longer be effective. Even strong ESG commitments may not prevent backlash from the host government or the public. In these circumstances, firms may reduce ESG investment or withdraw from the market entirely.

Based on the above analysis, we propose hypothesis H1:

H1. Geopolitical risk and ESG performance of multinational enterprises exhibit an inverted U-shaped relationship.

To further refine our theoretical framework, we draw on the FSA–CSA matrix developed by Rugman and Verbeke (2003) [

42], which has become a widely accepted model for analyzing MNEs’ behavior. In this framework, FSAs refer to unique, inimitable resources and capabilities that enable firms to overcome the “liability of foreignness” (LOF) in host markets. CSAs refer to location-based advantages rooted in either the home or host country—such as resource endowments, market size, or institutional quality. An MNE’s international investment strategy depends on both its motivation and capability to invest, both of which are shaped by its FSAs and CSAs of the host country.

Strong ESG performance can enhance productivity and competitive advantages, and can reduce investment risks in host countries. MNEs with large FSAs are typically better equipped to allocate resources toward ESG improvement. In turn, better ESG outcomes help internalize the locational advantages of host countries as part of the firm’s overall competitive advantage.

Moreover, host countries with higher standards for environmental protection, labor rights, and governance tend to encourage stronger ESG commitments from MNEs. Emerging market MNEs, which may lack the ownership advantages of developed-country counterparts, often use international expansion to acquire or leverage host-country CSAs. In such cases, CSAs become particularly critical, and host markets with stronger CSAs often demand higher ESG compliance. To establish legitimacy and market access, these MNEs may be especially motivated to improve their ESG performance. In short, FSAs determine the firm’s capability to enhance ESG performance, while CSAs shape their motivation to do so.

From a corporate strategy perspective, ESG investment reduces information asymmetry with investors, builds legitimacy, and strengthens stakeholder relationships. However, ESG efforts are not risk-free. When MNEs encounter opposition from host-country governments or the public—such as during nationalization, labor disputes, or other crises—even strong ESG performance may fail to alleviate tensions. In such cases, ESG strategies may prove ineffective.

As an exogenous factor, GPR indirectly affects corporate decision-making by shifting the risk–return profile of ESG performance. Under moderate GPR, the returns of ESG efforts increase due to enhanced legitimacy and reduced exposure to external shocks. In contrast, under high GPR, risks outweigh benefits, potentially discouraging firms from committing further resources—even when ESG investments align with strategic intentions (

Figure 2).

Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a. FSA is positively correlated with the ESG performance of multinational enterprises.

H2b. CSA is positively correlated with the ESG performance of multinational enterprises.

During periods of GPR, MNEs may adopt different strategies to manage risks. For example, under conditions of moderate geopolitical risk, firms may enhance ESG performance to ease pressure from host-country stakeholders and strengthen their legitimacy. Conversely, under high geopolitical risk, firms may adopt a contraction strategy.

FSA influence not only an MNE’s ability to improve ESG performance, but also its capacity to withstand geopolitical risks. High-FSA firms generally exhibit stronger risk resistance. They possess greater resource reserves, allowing them to maintain or improve ESG efforts during moderate levels of GPR. In addition, such firms tend to be more competitive and less replaceable in host-country markets, which strengthens their bargaining power. As a result, they are less likely to exit markets during periods of heightened geopolitical tension and are more likely to invest in ESG initiatives for long-term strategic reasons. Finally, high-FSA firms often have more international experience, making them better equipped to coordinate global resources and minimize the losses resulting from GPR.

CSA, by contrast, relates to the driving force behind ESG investment. In host countries with high CSA, MNEs are more inclined to invest in ESG performance, especially during periods of moderate geopolitical risk. Conversely, during high-risk periods, firms are more likely to exit low-CSA markets, which are often perceived as less stable or strategically valuable.

High-CSA host countries tend to offer greater political stability, encouraging MNEs to maintain long-term commitments and improve ESG performance. In contrast, low-CSA countries often present a more volatile geopolitical environment, discouraging firms from making substantial ESG investments during times of risk. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following additional hypotheses:

H3a. FSA positively moderates the relationship between GPR and the ESG performance of multinational enterprises.

H3b. CSA positively moderates the relationship between GPR on the ESG performance of multinational enterprises.