1. Introduction

Recent catastrophic climate-related events recorded worldwide—such as floods, landslides, and coastal erosion—have highlighted critical shortcomings in traditional top-down disaster management and risk communication strategies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These events, increasingly intensified by climate change, have amplified the necessity of effective, inclusive, and participatory risk governance processes [

6,

7,

8]. Indeed, risk communication, risk perception, and community behaviours are the foundations of any successful disaster risk reduction strategy [

9,

10,

11]. Among others, Adger et al. [

12] and Biesbroek et al. [

13] have emphasised that informed and adaptive communities are essential in responding effectively to climate-driven risks. Examples of risks amplified by climate change are sea level rise and coastal erosion; extreme precipitation and flooding; and wildfires, heatwaves and drought [

14,

15,

16].

Effective risk communication depends heavily on trust and clarity, necessitating meaningful interactions between citizens, stakeholders, and decision-makers [

8,

17]. Nonetheless, the translation of scientific knowledge into actionable community practices remains challenging, often hindered by fragmented communication strategies and insufficient stakeholder engagement [

4,

18,

19].

In this context, public consultations, defined by the United Nations [

20] as constitutional processes actively seeking input from citizens and organised groups, represent crucial mechanisms for integrating diverse perspectives into risk governance, particularly in the design and implementation of climate adaptation policies. Building upon this conceptual framework, it can be assumed that successful risk preparedness and response strategies must actively engage all community segments, including local authorities, scientific experts, stakeholders, and citizens [

8,

21]. Such comprehensive participation can be achieved through diverse methodologies, including surveys, focus groups, structured interviews, workshops, and innovative online platforms [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Engaging different representatives of a community can enhance the legitimacy, equity, and effectiveness of climate policies by incorporating local knowledge and fostering a sense of ownership [

12].

However, despite increasing emphasis on public participation in environmental and disaster governance, significant challenges remain.

Not all participatory processes lead to real influence, often being symbolic and lacking executive power [

8,

26]. This fact undermines effectiveness, fairness, and legitimacy of participatory processes, especially when local knowledge is ignored or involvement is poorly implemented. Social inequalities—such as socio-economic barriers, digital exclusion, and lack of awareness—can restrict access and representation, reinforcing vulnerability [

27,

28,

29]. Scholars warn that participation may become merely an “illusion of inclusion” if structural inequalities and power imbalances aren’t addressed [

27]. In the context of geo-hydrological risks, citizen engagement is further hindered by technical complexity and distrust in institutions, especially in communities with negative past experiences [

29,

30].

Therefore, while public participation is widely promoted as a pillar of resilience and adaptive governance, its implementation must go beyond procedural inclusion to foster genuine co-production, shared responsibility, and empowered deliberation. This requires clear communication, mutual trust, and institutional frameworks that support the continuity, transparency, and effectiveness of participatory risk governance.

While public consultation is a well-established approach in risk governance, its effectiveness is strongly tied to the inclusion of communities in emergency management processes, the enhancement of public preparedness and the development of population resilience [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Despite its recognised value, the assessment of the relative performance of the various consultation methods—including the tools and communication channels involved—remains a significant challenge. The effectiveness of any given method is context-dependent, varying according to regional characteristics such as topography, hazard typology, and the distribution of exposed and vulnerable elements [

36,

37,

38,

39].

This paper is an output of a broader Italian research project titled “REFOCUSING—Fostering climate change adaptation of local communities through a participatory risk communication strategy”, which aims at enhancing local risk communication strategies by improving stakeholder interactions, community engagement, and resilience to climate change. The scientific literature currently lacks a comprehensive and up-to-date review of the most effective public consultation methods applicable to geo-hydrological risk and its associated hazards. Indeed, the term “geo-hydrological risk” refers to the potential for damage caused by phenomena such as landslides, floods, and soil erosion, which result from the combined action of geological (geo) and hydrological (hydro) factors. It appears to be particularly prevalent in the Italian technical language, likely reflecting the country’s high susceptibility to combined processes due to its complex geological and hydrological setting [

40,

41]. This context-specific use of the term underscores the need for geographically nuanced approaches to risk communication and community engagement.

To this end, a systematic review on participatory methods, consultation tools and dissemination channels used in climate-related risk preparedness and response, was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [

42,

43]. More specifically, the objectives of the review were (i) assessing the state of the art on participatory processes, (ii) identifying strengths and weaknesses of the current risk communication processes, and (iii) recommending effective participatory practices that can be adapted and applied in local Italian contexts, thus facilitating better alignment between scientific knowledge, community perceptions, and policy actions. Two distinct but complementary streams of analysis were conducted. The first stream focused on a review of international scientific literature to identify overarching trends, theoretical models, and best practices concerning participatory approaches to climate change adaptation. The second one focused on the Italian context, through an in-depth exploration of national platforms dedicated to public consultation and participatory governance.

Ultimately, this research aspires to foster robust dialogues and collaborations between citizens and policymakers, urging communities to become active and informed participants in climate change adaptation and disaster risk management. The findings will be shared with the local administrations involved in the project’s case studies and made accessible to anyone interested in consulting them.

2. Materials and Methods

The review process focused on three interconnected thematic areas: climate change, geo-hydrological risks, and participatory consultation methodologies. The aim was to identify and collect peer-reviewed scientific articles, research studies, book chapters, reviews, and practical examples of participatory processes.

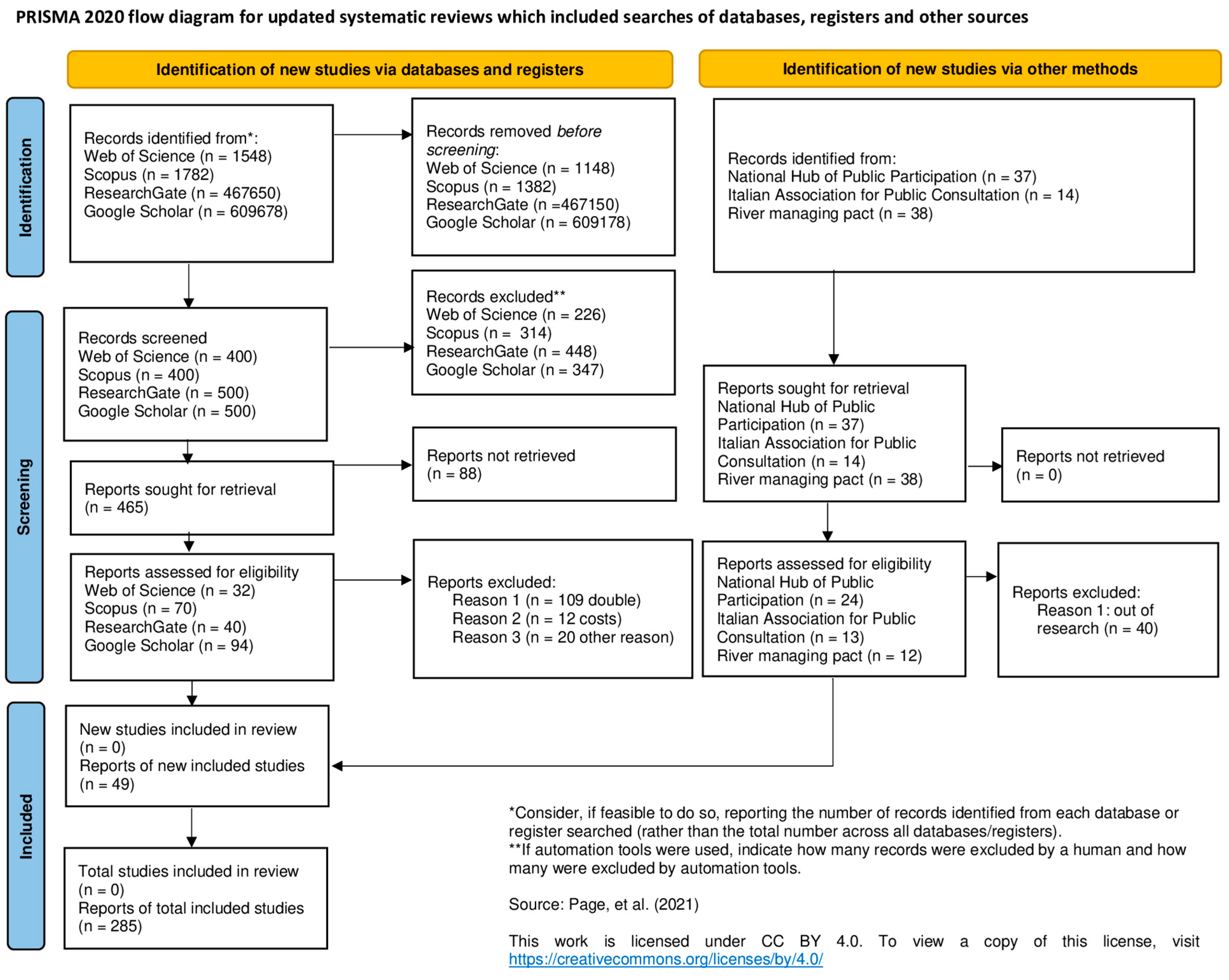

To ensure transparency, replicability, and methodological rigour, a systematic review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the PRISMA methodology. As outlined in

Figure 1, this approach comprises three sequential stages: identification, screening, and final inclusion of relevant studies. In the identification stage, comprehensive searches are conducted across selected databases and national public platforms, generating an initial set of records. During the screening phase, these records undergo preliminary examination of titles and abstracts to eliminate clearly irrelevant studies. In this phase, an eligibility assessment is also carried out which involves detailed evaluations of the remaining studies by reviewing introductions and conclusions, followed by full-text analyses to ascertain their alignment with the defined criteria. Finally, in the inclusion stage, studies that fully meet the eligibility requirements, namely contributing new knowledge on the subject of stakeholder engagement, are selected to undergo fully analysis. Each phase of the study is extensively described in the following paragraphs.

2.1. Identification of the Studies

A systematic search, updated to September 2024, was conducted across a wide range of academic and grey-literature sources to map participatory approaches to climate-related risks. The enquiry focused on three intertwined dimensions: climate change adaptation as a comprehensive multi-hazard framework; the specific geo-hydrological threats of floods, landslides and coastal erosion; and the consultation methodologies used to engage stakeholders.

To capture the relevant literature without inflating off-topic results, the identification phase adopted a controlled set of topic terms, each paired in Boolean AND with participatory qualifiers. Specifically, every core topic keyword was combined with both “Participatory Processes” and “Stakeholder Consultation” (e.g., “Flood” AND “Participatory Processes”; “Flood” AND “Stakeholder Consultation”), as reported in

Table 1. Two choices merit clarification. First, we included “Geo-hydrological Risk” because in Italy the term is widely used in both technical and scientific discourse and predominantly paired with risk rather than hazard; omitting it from search strings and eligibility criteria would have excluded relevant peer-reviewed contributions and practice-oriented case studies framed under this label. In our protocol, “geo-hydrological risk” denotes integrated treatments of floods and landslides. Second, we used “Climate Change Adaptation” (instead of the broader “climate change”) to constrain scope to adaptation-oriented participatory governance and avoid generic climate topics unrelated to preparedness and response. This structured syntax ensured that both conceptual and applied studies were retrieved across disciplines, while maintaining thematic precision (

Table 1).

Four interdisciplinary academic databases, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, Scopus, and Web of Science, were selected for their relevance to environmental, social, and applied research. Combined queries produced 1,020,658 records (

Table 1). Then, to privilege recency, citation weight and topicality, the selection was limited to the first five results pages per engine, with duplicates deleted and obviously off-topic items discarded. The process yielded 1800 unique academic references: 500 from Google Scholar, 500 from ResearchGate, and 400 each from Scopus and Web of Science. Frequency analysis confirmed a strong skew towards flood-related research, moderate attention to landslides and coastal erosion, and an interesting absence of papers linking “geo-hydrological risk” with participatory keywords in Scopus and Web of Science. Such gap is partially offset by broader phrases such as “flood” or “landslide” combined with “participatory processes”. All records were compiled into a collaboratively managed online database, which was constantly refined to remove residual duplicates and track inclusion or exclusion decisions.

Recognising that peer-reviewed literature seldom captures the full spectrum of on-the-ground practices, we extended the searches by selecting the three most relevant Italian national forums of stakeholder consultation: (i) the Italian Association for Public Consultation (Associazione Italiana per la Partecipazione Pubblica—IAPC,

https://www.aip2italia.org/, accessed on 23 September 2025), a nationwide archive of public engagement examples addressing territorial issues related to climate change, (ii) the River Contracts (Contratti di Fiume—RC,

https://www.contrattidifiume.it/, accessed on 23 September 2025), which documents stakeholder platforms focused on flood-risk governance along river basins, and (iii) the National Hub of Public Participation (ParteciPa—PP,

https://partecipa.gov.it/, accessed on 23 September 2025), which is focussed on land and cultural heritage preservation. These portals exemplify deliberative democracy in Italy by showcasing protocols, toolkits and case studies where citizens and institutions co-manage public concerns. They play a crucial role in involving both citizens and institutions in decision-making processes related to the public interests, especially in the areas of sustainable resource management and local development. Eighty-nine grey records passed a preliminary relevance filter and were merged with the academic corpus: 38 from RC, 37 from PP and 14 from IAPC. Their addition brings the working dataset to 1889 entries, offering a balanced view of scholarly discourse and operational reality. Accordingly, subsequent screening, eligibility assessment and coding processes apply thematic, temporal and geographic filters aimed at distilling transferable insights while retaining sufficient diversity for cross-hazard comparison.

2.2. Defining Eligibility Criteria

The selection of the studies followed a predetermined set of eligibility criteria aimed at ensuring both methodological consistency and thematic alignment with the objectives of the research, namely extracting participatory strategies for climate change adaptation that can be realistically deployed in the Italian context, where the two case studies of the PRIN project are situated. First, the review of international scientific literature retrieved from major academic databases was conducted considering English-language peer-reviewed articles. In this way, the review captured a broad and diverse body of evidence, offering comparative insights and supporting the generalisation of findings within the broader European context. Conversely, grey literature originating from the national public platforms dedicated to participatory governance are often available only in Italian. Thus, the inclusion of Italian language documents was necessary not only for linguistic accessibility but also for capturing the richness and specificity of national practices that are directly relevant to local realities. Another eligibility criterion was the geographic focus, which was confined to Europe. Governance systems, legal regimes and socio-cultural norms in other continents differ markedly from those in Italy, which would compromise transferability. By excluding extra-European case studies, we can ensure analytical relevance and avoid misleading extrapolations. Moreover, temporal boundaries were set between 2000 and 2024. This 25-year window captures the period during which participatory governance moved to the centre of international risk-management agendas, spanning the Hyogo Framework for Action, the Sendai Framework and the European Green Deal, while filtering out obsolete approaches that may no longer reflect current technological standards, regulatory environments, or institutional practices. Furthermore, only documents available in open-access repositories or on institutional websites were retained, ensuring that practitioners and policymakers can consult the underlying evidence without subscription barriers and thereby facilitating knowledge transfer beyond academia. Another key inclusion criteria guiding the selection process was the breadth of stakeholder engagement. Eligible records had to describe consultation processes open to a wide constituency: municipal administrations, civil protection and emergency services, technical offices, researchers, local media, business representatives, educators, NGOs and citizens. Such diversity is crucial for mainstreaming adaptation because it mirrors the fragmented competencies typical of Italian risk governance. Conversely, studies exclusively targeting narrow subgroups (e.g., people with rare diseases or highly specialised professions) were discarded, as their insights cannot readily inform community-wide planning. Finally, each record was reviewed by at least two researchers; disagreements were settled by consensus, and decisions logged in a shared repository.

2.3. Implementation of the Analysis

The analytical process of the review was conducted following a structured, multi-step protocol designed to ensure methodological transparency, reproducibility, and relevance. After the identification phase, which generated 1800 records from academic databases and an additional 89 from grey literature sources, all documents were processed through two main stages: screening and inclusion.

The screening phase began with a review of titles and abstracts, resulting in the removal of clearly ineligible records. The reasons for exclusion at this stage were extrapolated from the eligibility criteria (irrelevance, redundancy, a non-European focus, paywall restrictions and language). Documents that passed this first filter were then assessed based on their introductions and conclusions. Full-text analysis was conducted only in the subsequent phase. During this phase, 448 records from ResearchGate, 347 from Google Scholar, 314 from Scopus, and 226 from Web of Science were excluded, retaining a total of 465 academic records for detailed scrutiny. Parallel screening was applied to 89 dossiers from Italian stakeholder portals, which formats differ from journal articles, thus bespoke criteria were used: explicit climate-risk focus, participatory objective, and documentation of at least one completed activity rather than an aspirational plan. All 89 met these basic checks and progressed.

The inclusion phase involved an in-depth reading conducted by two independent reviewers to verify alignment with the following dimensions of evidence quality: (i) design limitations, (ii) internal coherence, (iii) precision of reported outcomes, (iv) contextual fit with Italian governance, and (v) publication bias (e.g., project websites reporting only successes). Consistent with the scope of a PRISMA review, we did not carry out a formal risk-of-bias scoring or a detailed re-assessment of each study’s research design, sample representativeness, or statistical analysis. Peer-reviewed articles were assumed to have already undergone basic scientific scrutiny in their original publication venues. Our evidence-quality checks therefore served primarily to determine eligibility and to inform the narrative weighting of studies, rather than to rank or rate individual designs. Where disagreement arose, discussion led to a final decision, which was systematically logged in a continually updated and shared database. Where applicable, researchers provided justifications for downgrading or upgrading the certainty of the evidence, clearly documenting their reasoning in footnotes and annotations. This rigorous peer assessment process enhanced the scientific reliability and robustness of the review outcomes. After this refinements, 94 studies from Google Scholar, 70 from Scopus, 40 from ResearchGate, and 32 from Web of Science, were assessed for eligibility. From the grey literature, 24 participatory cases from National Hub of Public Participation, 13 from the Italian Association for Public Consultation, and 12 from River Contracts were also included in the eligibility check. Altogether, 285 documents (including both academic and grey literature sources) passed the full eligibility check and were included in the final analysis. The final pool of included documents represented a balance of international academic literature and nationally grounded examples. A full bibliographic list is available in the

Supplementary Materials.

Once included, all records were systematically catalogued in a relational database with core bibliographic metadata (year, title, reference) complemented by several analytical fields covering topic, objective, thematic focus, methods and tools of consultation, types of stakeholders involved, scale of implementation, communication channels, expected results, and critical issues encountered (

Table 2). To ensure consistency and comparability of data, several methodological conventions were adopted for classifying consultation methods, tools, and dissemination channels from the reviewed scientific articles. For instance, workshops were classified under either the methodological category “survey” or “public event”, based on their organisational setup and the type of participants involved. Other volunteer-based data collection initiatives (such as participatory mapping, video games or e-learning platforms) were treated as “surveys” and/or “online” tools, since they primarily rely on structured reporting by participants. Where original texts were vague, coders met to agree on the most plausible classification; persistent ambiguity triggered assignment to “other” with an explanatory note. This allowed us to capture the diversity of practices while maintaining a coherent analytical framework across regions and hazards.

During full-text screening and extraction, we also inspected whether sources reported the number of participants involved. Reporting proved highly inconsistent across records (many studies did not specify sample sizes, reported only partial figures, or used incomparable units). To avoid selection bias and misleading cross-tabulations, participant counts were not included in the quantitative synthesis and are not part of the analytical fields listed in

Table 2.

The analysis of the review’s outcome employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques. Thematic content analysis was used to identify trends, emerging approaches and methodological gaps. Meanwhile, frequency analysis allowed key elements, such as the prevalence of specific consultation tools or communication channels, to be quantified. To further ensure data comparability, the results were normalised using relative percentages. This integrated approach provides a nuanced understanding of participatory practices in different contexts and helps to identify best practices for stakeholder consultation in climate change adaptation and geo-hydrological risk reduction.

3. Results

A total of 285 documents passed the multi-stage eligibility filter: 236 peer-reviewed papers and 49 practice-oriented case studies harvested from three national engagement portals (Italian Association for Public Consultation, River Contracts, and National Hub of Public Participation). The final dataset reflects a well-balanced integration of theoretical frameworks, empirical research, and real-world applications. Such multifaceted corpus enables the identification of methodological patterns, context-specific innovations, and replicable practices across different domains of environmental governance. To ensure comparability and transparency, and in consistency with the PRISMA review framework, this section is intentionally structured to analyse aggregated patterns across hazards, participatory methods, and stakeholder groups, rather than individual case narratives.

3.1. Thematic Categorisation and Scope of the Analysed Literature

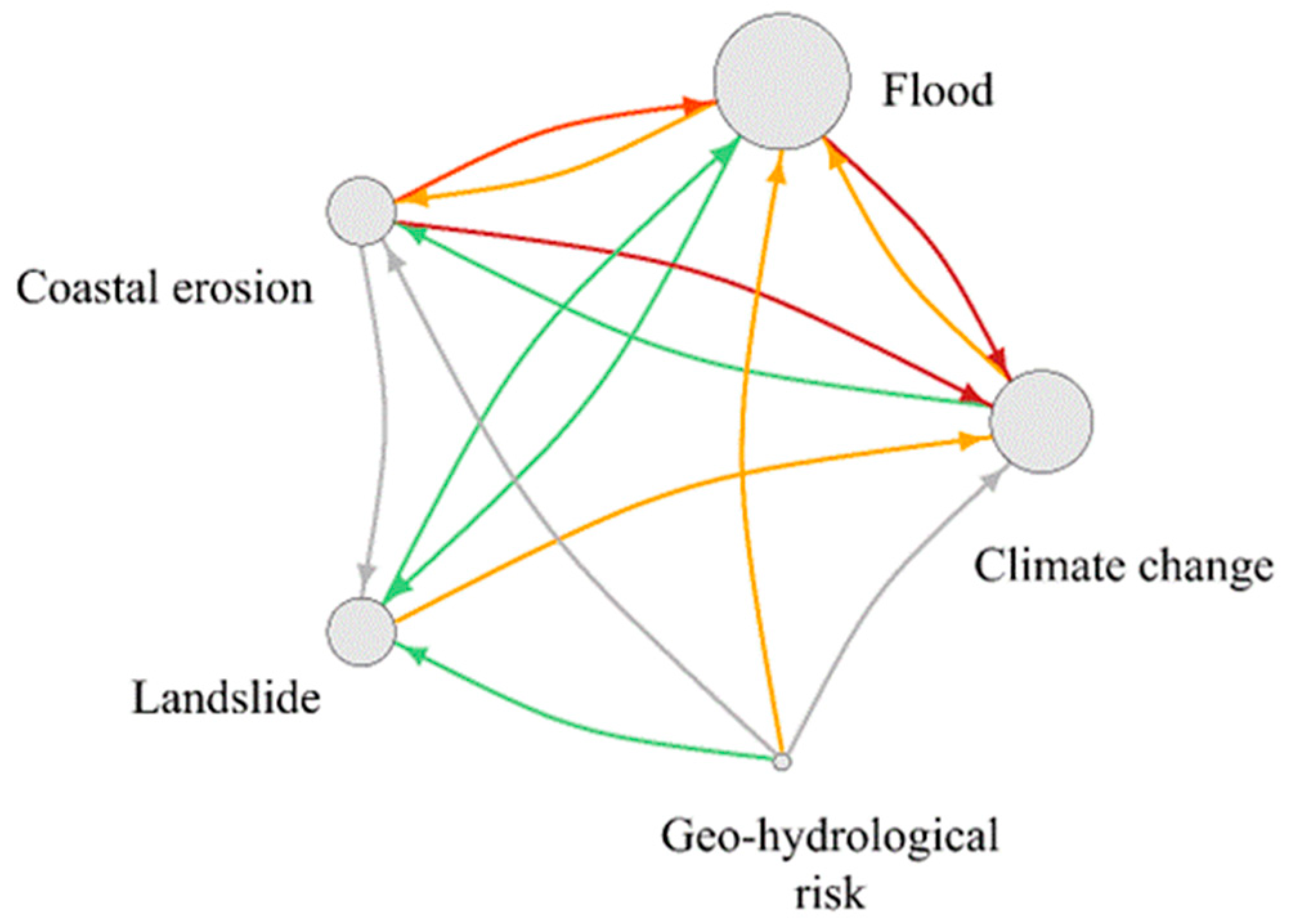

The academic component of the review was organised around the five-hazard domain introduced in the methodological section: floods, landslides, coastal erosion, geo-hydrological risk and climate change. Scholarly attention proved markedly uneven: 41% of the papers (96) concentrated on floods (see

Supplementary Materials Table S1) and 28% (67) on climate change (see

Supplementary Materials Table S2), while coastal erosion (34) (see

Supplementary Materials Table S3), landslides (27) (see

Supplementary Materials Table S4) and integrated geo-hydrological risk (12) (see

Supplementary Materials Table S5) accounted for progressively smaller shares. These categories, however, are not mutually exclusive. Not only does the term “geo-hydrological risk” denote an integrated approach to floods and landslides, but a significant portion of the literature also addresses multiple hazards simultaneously. For instance, numerous climate change articles frequently analyse flood management or shoreline retreat, while studies on landslides regularly invoke the broader construct of geo-hydrological risk. A network analysis visualised in

Figure 2 renders these interconnections graphically: red arrows denote the prolific co-occurrence of the climate change keyword in more than 20 articles covering the topics of flood and coastal erosion, while orange, yellow, green, and grey lines indicate progressively weaker overlaps (respectively, 15–20, 10–15, 5–10, and less than 5 articles). This clustering pattern thus confirms the high degree of thematic integration in the literature, particularly between flood risk and climate change and between coastal erosion and climate change. However, it also highlights the relative scarcity of papers linking integrated geo-hydrological perspectives to climate change. The peripheral position of multi-hazard thinking suggests conceptual silos that future research would do well to breach.

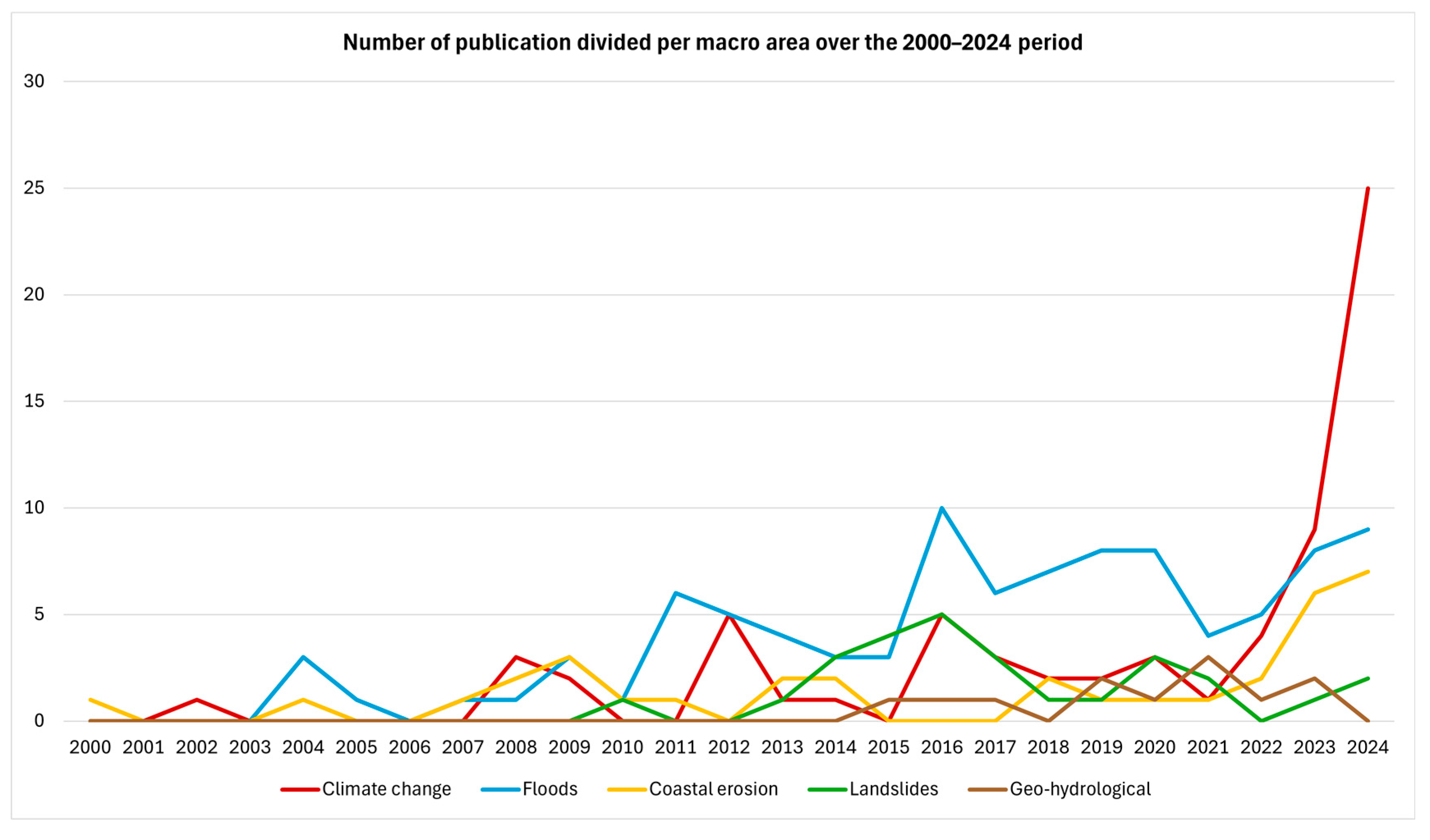

A diachronic reading of the literature reinforces this impression.

Figure 3 shows publication numbers over the period 2000–2024 and reveals two steep curves: the first for flood studies, which increased rapidly in 2016; and the second for climate change adaptation studies, which accelerated in 2023 and almost tripled the following year. Steady but smaller gains in the number of papers on landslides and coastal erosion hint at growing interest in these topics, yet the gentle slope also signals that significant knowledge gaps persist. A different path is discernible for geo-hydrological risk: the term only begins to appear alongside community engagement and participatory processes in 2015 but does not increase in subsequent years. The smaller but still increasing number of studies on coastal erosion, landslides, and geo-hydrological risks points to areas where further scholarly attention may be warranted. Indeed, this figure serves not only as a quantitative representation of the publication volume, but also as an indicator of shifting research priorities over time. The steep curve in flood-related publications corresponds to the growing recognition of hydrological extremes as central components of climate adaptation. Similarly, the rise in climate change-related literature aligns with global policy milestones (e.g., the 2015 Paris Agreement) and an increased demand for participatory approaches in mitigation and resilience planning.

In contrast, the participatory case studies identified from the three Italian institutional platforms did not always provide thematic classifications comparable to academic indexing (see

Supplementary Materials Table S6). Specifically, 24 examples from the ParteciPa gravitate towards land use planning, social inclusion, green infrastructure, and sustainable urban development. River Contracts 12 case studies predominantly focus on flood management and watershed governance. The Italian Association for Public Consultation provided 13 projects emphasising cultural heritage, sustainable development, public health, and community resilience. Hence, unlike in academic literature, the thematic overlap is less pronounced. In other words, each portal tends to specialise in particular domains, i.e., RC water-related issues, PP social and environmental sustainability, and IAPC cultural and institutional engagement. This thematic divergence reflects the platforms’ institutional missions and target audiences, reminding that scholarly agendas and practical priorities do not always coincide and that any effort to translate research insights into policy must be sensitive to the varied mandates of implementation programmes.

3.2. Participatory Methods, Tools and Channels

Across the corpus a variety of methods, tools, and dissemination channels are employed to facilitate stakeholder participation in geo-hydrological risk preparedness and response. These participatory approaches reflect diverse strategies intended to foster inclusive dialogue, empower communities, and ensure informed decision-making processes.

Observing the outputs of the academic literature, surveys emerge as the dominant consultation method in every hazard category, accounting for 43% to 67% of reported activities (

Table 3). They offer significant advantages due to their scalability, structured or semi-structured approach, and potential to gather quantifiable and comparable data. Nonetheless, their effectiveness heavily depends on questionnaire design and sample representativeness, factors occasionally overlooked in practice. Focus groups and discussion forums stand as the next most common options, valued for their capacity to facilitate interactive exchange and allow nuanced exploration of stakeholders’ perspectives, values, and priorities. Despite being less prevalent, public events and meetings are critical for fostering transparency and community trust, although their lower frequency of use might be attributable to logistical challenges or limited financial and human resources.

In terms of consultation tools, semi-structured interviews stand out as the most prevalent across various thematic areas, accounting for between 44% and 53% of preferences (

Table 4). Workshops can also be classified as semi-structured interviews, as long as they are methodologically flexible enough to explore specific themes without biasing participant responses. This preference underscores the need for flexibility in discussions, accommodating unforeseen stakeholder insights while maintaining structured data collection. Interestingly, however, geo-hydrological risk studies deviate from this pattern. In fact, only twelve papers in the entire corpus address this multi-hazard category, and three-quarters of these rely on highly standardised instruments, favouring structured questionnaires (55%) and structured interviews (27%). This preference for tightly predefined formats likely stems from the need to compare responses across multiple hazard types (e.g., floods and landslides). The preference for these formats may be linked to the heightened need for consistency, comparability and objectivity in data collection, which is probably more essential in geo-hydrological risk contexts where accurate assessment underpins hazard modelling and policy development. Conversely, less structured methods such as unstructured questionnaires and unstructured interviews were notably rare, presumably because the analytical effort required to transform rich narrative data into actionable insights is seldom matched by available resources.

Communication channels mirror these methodological preferences. Analysis reveals a clear preference for face-to-face (33–63%) and online (25–40%) approaches (

Table 5), demonstrating the dual tendency to build trust through direct interaction and to use digital communication for greater efficiency and a broader reach. Face-to-face approaches dominate in all hazard areas, especially coastal erosion and landslides, where direct community interaction is essential to convey urgency and ensure comprehensive understanding of the issue, which is often geographically bounded. Online methods, including e-mails, mobile apps, social media platforms and interactive websites, have grown steadily, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic normalised remote engagement, and now constitute the second pillar of participatory communication. However, traditional media such as newspapers, radio, and television, feature only sporadically. This could undermine outreach to older or less digitally connected demographics. Notably, a residual “other” category comprising innovative participatory approaches and channels has started to gain attention. These include organised field visits to areas identified as being at risk as well as creative workshops designed to be accessible to participants across all age groups. Such activities not only facilitate knowledge exchange but also promote deeper, place-based understanding of geo-hydrological risks. In parallel, recent studies have begun to investigate more indirect methods of data collection and public engagement. For instance, the analysis of citizen-generated content, such as comments, mentions, and discussions on social media platforms, has emerged as a valuable source of insight into public perception and behaviours related to risk preparedness and response. Such innovative practices signal a shift towards experiential and playful formats intended to broaden appeal across age groups and social strata.

The Italian case studies emerging from the national public platforms broadly mirror the academic patterns yet push them further. Although details on methods, tools and channels are not always reported systematically in the portal documents, the available information points to clear convergences: surveys and public events emerge as the most employed consultation methods; structured questionnaires and semi-structured interviews are the most frequently data collection tools; and communication relies mainly on a face-to-face/online mix. What distinguishes the portals is the breadth of their “other” category for dissemination—ranging from open calls for comments and proposals, to creative laboratories, world cafés, bar camps and guided field trips. This experimental inclination is consistent with their mandate as laboratories of public engagement and underscores a fertile interface where academic rigour can meet practitioner ingenuity.

Table 6 synthesises these distributions across the three platforms (IAPC = Italian Association for Public Consultation; RC = River Contracts; PP = ParteciPa).

In such a diverse and multifaceted scenario, consultation effectiveness hinges not only on the selection of techniques but also on whom those techniques reach and at what geographical scale they are deployed. The next section therefore interrogates stakeholder composition and implementation scales to clarify how participation is configured in practice and how these choices condition outcomes.

3.3. Stakeholder Involvement and Scale of Implementation

The review of scientific articles revealed a consistent pattern in the categories of stakeholders involved in participatory processes (

Table 7). The most frequently engaged groups across all thematic areas (climate change, coastal erosion, flooding, geo-hydrological risk and landslides) were citizens, municipal authorities, municipal technical offices, specialists or professional experts, universities and research institutes, and voluntary associations. Their involvement indicates widespread recognition that effective risk governance must combine institutional authority, technical competence and community legitimacy into participatory processes. Yet, several potentially influential groups show consistently lower levels of engagement across thematic areas. These include local media, religious organisations, district councils, cultural institutions such as museums, insurance agencies, health and emergency services, and local industry representatives. This lower level of engagement may be due to the perception that these groups are less directly affected by or relevant to the risks. However, excluding these groups could also foregoes the communicative power of trusted intermediaries, the social capital of faith-based networks and the financial leverage of risk-pooling mechanisms. For example, local media outlets can amplify risk awareness messages significantly, religious organisations often have strong community relationships and cultural institutions can facilitate innovative engagement and educational activities. Strategically including these underrepresented stakeholders could therefore improve the effectiveness, diversity and cultural appropriateness of participatory processes.

The grey-literature cases display some differences compared to the academic literature, demonstrating greater diversity and inclusiveness in stakeholder involvement (

Table 8). Specifically, whereas citizens, municipal authorities, municipal technical offices, specialists or professional experts, and voluntary associations were similarly prominent, the national platforms show higher frequencies for stakeholder categories that are peripheral in academic studies: mayors, local industries, religious associations, district councils and cultural/recreational groups appear more often, particularly in the Italian Association for Public Consultation (IAPC) and ParteciPa (PP) datasets. This broader inclusiveness likely reflects the platforms’ bottom-up orientation, which aims to encourage extensive community engagement and represent a more diverse range of local interests, as opposed to the predominantly expert-oriented focus observed in the academic literature.

Nonetheless, even within these practice cases, some actors continue to be scarcely involved. Local media, insurance agencies, museums, police forces and health services register very low values across all three portals, indicating that their marginalisation is not merely an artefact of academic sampling but a broader systemic pattern. Therefore, key communicative, cultural and financial intermediaries remain at the margins in both tables. A further divergence concerns universities and research institutes: while they are highly visible in the academic corpus, they appear far less often in the national participation platforms. This likely reflects a tendency for universities and research groups to engage primarily in processes they initiate or in which they are formal partners; when projects originate from administrations or civic networks, academia tends to remain in the background, often confined to ad-hoc advisory roles. Recognising who is repeatedly absent is as important as cataloguing who is present. Bringing these “quiet stakeholders” into the process, not only as recipients of information but as co-designers of strategies, could substantially improve the diversity, legitimacy and practical effectiveness of participatory initiatives.

Scale of implementation further differentiates academic and practical endeavours. More than half of peer-reviewed interventions operate at municipal level (

Table 9), suggesting that participatory processes primarily focus on local governance structures and community-specific interventions. A logical choice given that municipalities control land-use planning, emergency management and public-works budgets. Conversely, individual-scale pilots and district-level experiments are scarce, likely reflecting administrative, logistical, or resource-related constraints. Furthermore, a considerable number of cases were classified under the “other” category, typically indicating implementation at an inter-municipal, regional, or national scale, particularly for climate change adaptation. Such implementations are typically reserved for initiatives that require extensive regulatory frameworks or substantial financial resources and that often address broader geographical challenges.

Different trends emerge from the analysis of national platforms (

Table 10). The scale of implementation within these platforms varied significantly: while the Italian Association for Public Consultation included initiatives at individual (31%) and municipal (23%) scales, nearly half (46%) utilised alternative scales categorised as “other”, predominantly representing regional or national implementation. In contrast, River Contracts and the National Hub of Public Participation exclusively adopted broader territorial scales (100% categorised as “other”), such as river basin, inter-municipal, regional, or national frameworks. This preference for larger territorial frameworks likely reflects the platforms missions oriented toward holistic governance of shared resources, inter-municipal cooperation, and integrated territorial planning, rather than isolated local interventions.

The significant difference in scale of implementation between the academic literature, which focuses on municipalities, and the Italian platforms, which operate at a broader territorial scale, highlights contrasting governance logics. Researchers prioritise contextual specificity, whereas institutional platforms pursue multi-level coordination to address transboundary dynamics and financially demanding interventions. Recognising these distinctions is crucial for designing participatory strategies that are both inclusive and fit for purpose. Methods must align with data needs and community capacities; stakeholder range should be widened to incorporate communicative and cultural intermediaries. The spatial scope of engagement must mirror the geographical footprint of the hazard under consideration. In the discussion that follows, we draw on these empirical insights to outline design principles capable of enhancing the legitimacy, effectiveness and scalability of participatory climate risk governance strategies.

4. Discussion

The systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of participatory approaches within the context of climate-related geo-hydrological risks. A significant strength of this study lies in the balanced integration of theoretical frameworks, empirical research, and practice-oriented cases, thereby offering a robust foundation for practical and policy recommendations [

8,

44,

45,

46]. The growing interest among researchers and institutions in these issues is likely due to the intensifying effects of climate change and the increasing frequency of catastrophic events. While researchers focus primarily on the causes of these phenomena and strategies for adapting to the effects of climate change, institutions are interested in updating emergency response plans within their jurisdiction, enhancing territorial protection measures and gaining a scientific understanding of ongoing environmental transformations. Nevertheless, the review highlights several common trends and a number of critical gaps and asymmetries in the current body of literature.

Firstly, the pronounced thematic concentration on flood risks, evident from the majority of academic studies, aligns closely with recent increases in European flooding events post-2016 [

47,

48]. Such heightened attention is likely attributable to the visibility of flood events and their substantial socio-economic impacts, thus directing both research funding and public engagement efforts predominantly toward this hazard type [

49,

50,

51,

52]. Moreover, in many large-scale studies, floods have exhibited higher or more readily observable fatality impacts than other hazards, including landslides and coastal erosion [

53], which may further explain the disproportionate academic focus and policy interest toward flood-related studies. Similarly, the growing body of climate change-related literature reflects the influence of global policy milestones (e.g., the 2015 Paris Agreement) and an increased societal and institutional demand for participatory approaches in mitigation and resilience planning (IPCC, 2022). However, as the results clearly indicate, this thematic bias raises concerns about the relative neglect of other significant hazards, such as landslides and coastal erosion, which equally require participatory engagement but remain underrepresented [

27,

54,

55,

56]. Addressing these research imbalances is critical, as other hazards pose equally significant threats and demand tailored participatory frameworks responsive to their specific impacts [

57,

58,

59]. Moreover, the limited integration of multi-hazard frameworks within participatory studies constitutes a significant conceptual shortfall. Only twelve articles explicitly focused on geo-hydrological risks, indicating a conceptual gap that limits comprehensive risk governance [

60,

61,

62]. Given that geo-hydrological risks inherently involve interconnected phenomena like floods and landslides, the scarcity of multi-hazard assessments represents a missed opportunity to develop comprehensive management strategies [

63,

64,

65]. Integrating multi-hazard perspectives into participatory governance strategies is increasingly recognised as essential for holistic disaster risk reduction [

66,

67].

Secondly, the various solutions adopted for the development of effective and up-to-date participatory strategies appear to be broadly similar across the studies reviewed. In general, surveys in the academia and surveys and public events in the national platforms emerge as the most frequently applied and effective approaches. These methods are likely perceived as highly engaging for community-wide involvement, or, alternatively, they may be favoured due to their relatively low demands in terms of financial and human resources [

44,

68]. In fact, the review also highlights that financial aspects of consultation activities are seldom detailed in the analysed literature. Only a limited number of studies explicitly address the costs associated with stakeholder engagement. Nevertheless, there is a clear preference for cost-effective methods that rely on existing personnel, infrastructure, and institutional capacities. This tendency suggests a pragmatic approach, whereby consultation strategies are shaped by available resources and implemented with minimal financial burden. However, there is a notable lack of detailed cost–benefit analyses of the participatory methods in the literature, underscoring a significant gap that future studies should address to better inform resource allocation in participatory risk governance [

69]. A systematic comparison of the relative effectiveness of individual participatory methods across regions and hazard types would require more consistent outcome reporting than is currently available and therefore remains an important task for future evaluation-focused studies.

Regarding participatory tools, the dominance of semi-structured interviews across thematic areas and literature corpus underscores the importance of methodological flexibility [

24,

70]. Such flexibility allows the accommodation of diverse stakeholder insights, enhancing the adaptability of participatory methods. Nevertheless, within the limited geo-hydrological risk studies, there is a clear preference for structured questionnaires and structured interviews, reflecting the necessity for precise and comparable data collection when addressing multiple interconnected hazards [

71]. This divergence highlights a crucial consideration for practitioners: participatory processes must balance stakeholder inclusiveness with the need for structured, actionable data suitable for comparative hazard analyses and effective policy formulation. Future research could explore how methodological rigour in structured approaches can complement the qualitative richness offered by more flexible methods [

44,

72,

73].

In terms of consultation channels, both online and face-to-face formats are frequently adopted. These channels likely offer the advantage of reaching a broad demographic, from younger to older members of the community, while also facilitating direct and meaningful engagement. The case studies derived from Italian national participation platforms reinforce these methodological patterns while simultaneously introducing innovative practices rarely documented in the academic literature. Examples such as creative laboratories, world cafés, bar camps, guided field trips, and social media storytelling highlight practitioner ingenuity and suggest fertile ground for methodological cross-pollination. Nonetheless, systematic documentation and evaluation of these innovative practices remain limited. Future research should systematically document these approaches, enriching the evidence base and informing the development of novel participatory methods [

24,

60,

73].

The stakeholder engagement analysis further illuminates critical issues regarding inclusivity and representation. The most frequently involved stakeholders in participatory processes are generally citizens, volunteer associations, researchers (including those from universities and research institutes), and representatives of local administration, such as mayors and municipal authorities and technical offices. Their prominent role reflects a general consensus on engaging actors with direct institutional responsibilities or scientific expertise. However, there is a tendency to involve citizens as a broad, generalised group, rather than identifying and engaging with specific stakeholder categories. Stakeholders who are consistently underrepresented, including local media, insurance agencies, health services, museums, cultural institutions and local industries, remain marginalised despite their potential as influential intermediaries [

67]. Their limited participation is striking, given their ability to amplify risk communication, enhance social capital, and provide financial and organisational resources. This lack of stakeholder differentiation may limit the effectiveness of communication strategies by overlooking the unique capacities of certain groups to act as trusted intermediaries and disseminators of risk-related information. A more strategic approach, targeting specific stakeholder categories and assigning them clearly defined communication roles could substantially enhance the reach, clarity, and credibility of emergency communication efforts. Such an approach would support the development of tailored engagement strategies, strengthen local networks, and foster community resilience in the face of geo-hydrological risks. Furthermore, despite their visibility in academic literature, universities and research institutes exhibit significantly lower engagement in national participatory platforms, highlighting academia’s tendency to participate mainly in projects they initiate or lead directly [

24,

74,

75]. Encouraging proactive academic involvement in externally driven initiatives could substantially enhance methodological rigour and innovative engagement strategies.

It is also worth noting that, across the corpus, the reporting of participant numbers is sparse and uneven. Many papers either omit sample sizes or provide partial figures that are not comparable across hazards, scales and methods. To avoid selection bias and misleading cross-tabulations, we therefore did not include participant counts in the quantitative synthesis. This lack of consistent documentation limits external validity checks and hinders cross-study comparability of participatory outcomes. We recommend that journals and institutional portals standardise minimal reporting for participatory studies, including (i) total participants and stakeholder composition, (ii) recruitment/sampling strategy, and (iii) response rates where applicable, to enable robust quality appraisal and evidence accumulation.

Finally, the review identifies the municipal scale as dominant within the research corpus, reflecting local governance structures’ crucial role in risk management. In contrast, national platforms frequently adopt broader territorial scales, reflecting strategic priorities for multi-level governance and integrated territorial management. This marked difference in scale emphasises the necessity of tailoring participatory processes to specific governance contexts and territorial challenges [

21,

76]. Municipalities offer localised responsiveness, while broader territorial scales facilitate essential coordination and management of cross-boundary hazards. Future participatory strategies should thus carefully align their methodologies with the specific governance scale and territorial context.

Certainly, this systematic review is subject to a few limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the practical cases derive from three Italian participation platforms, which provide valuable insights but are not representative of all European experiences. Second, reporting inconsistencies in the number and characteristics of participants across the reviewed studies limited the possibility of more detailed comparative analyses. Third, most of the documents and case studies are not geo-referenced, preventing spatial exploration of participation patterns. These aspects may affect the generalisability and resolution of our findings but do not compromise their overall validity. Future work could address these constraints by expanding the analysis to European-scale participation platforms, improving metadata reporting standards, and promoting geo-referenced documentation of participatory practices.

5. Conclusions

The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly frequent and severe. Risk communication is a fundamental component of the emergency planning process, playing a crucial role in both the preparation phase and the emergency response phases. In this context, it is essential for the entire community to be informed at all levels about how to respond and adapt to climate-related risks. A literature review was carried out with the aim of providing critical insights into the current state of participatory governance strategies employed in addressing climate-related geo-hydrological risks in Europe, with a particular focus on practical Italian case studies. Through rigorous analysis following the PRISMA statement guidelines, the study identifies key thematic trends, methodological preferences, stakeholder involvement patterns, and implementation scales. These insights serve as foundational elements to advance both theoretical understanding and practical applications within the field of disaster risk management.

The review reveals a clear academic bias toward flood risk management and climate change adaptation, consistent with recent global events and policy responses such as the Paris Agreement. However, other significant geo-hydrological risks, including landslides, coastal erosion, and integrated multi-hazard frameworks, remain inadequately explored, presenting substantial gaps in participatory governance literature. Addressing these imbalances is critical, as comprehensive hazard management strategies necessitate inclusive, multi-risk approaches capable of capturing the complexity of interconnected hazards.

Surveys and semi-structured interviews emerged as primary tools due to their flexibility and capacity for engaging diverse stakeholders. However, structured methodologies were preferred for multi-hazard studies due to the necessity for standardised data collection. This methodological divergence emphasises the need for balancing flexibility with analytical rigour, ensuring both rich qualitative insights and comparable quantitative data for robust policy formulation. Additionally, the prominence of face-to-face and digital communication channels underscores the need for versatile dissemination strategies to maximise stakeholder reach, especially within increasingly digitalised societies.

Stakeholder involvement patterns identified citizens, local authorities, specialists, and voluntary organisations as central to participatory processes. Nonetheless, the recurrent marginalisation of critical intermediaries, such as local media, insurance companies, cultural institutions, and universities, highlights a strategic oversight. These stakeholders possess unique capacities for amplifying risk communication, mobilising resources, and enhancing community resilience. Particularly noteworthy is academia’s limited engagement in externally initiated participatory projects, suggesting that academic institutions could significantly enhance participatory governance through proactive involvement beyond research-driven initiatives.

Implementation scales also revealed significant differences between academic and institutional approaches. While academic literature predominantly emphasises municipal-scale interventions tailored to localised needs, national engagement platforms frequently adopt broader territorial scales. This divergence highlights contrasting strategic priorities, underscoring the importance of aligning participatory strategies with governance contexts and territorial challenges. Effective risk governance thus requires balancing localised responsiveness with multi-level coordination capable of addressing broader socio-environmental dynamics.

Building on these reflections, future research should focus on the practical integration of participatory risk-management frameworks across different hazard types. Comparative analyses could explore how participatory tools support the balancing of priorities and resources among floods, landslides, and coastal erosion, as well as how they can foster cross-sectoral coordination and adaptive resource allocation. Developing integrated multi-hazard governance models that connect participatory decision-making with technical risk assessment and cost–benefit evaluation would strengthen the operational relevance and inclusiveness of risk management strategies. In addition, future work should extend the geographical scope of the analysis to European-wide consultation platforms, promote the geo-referencing of participatory cases, and enhance reporting standards, especially regarding participant numbers, sampling strategies, and outcomes. These improvements would enable comparative assessments of participatory quality and effectiveness.

Overall, this review highlights four strategic research priorities: (i) thematic diversification beyond flood-dominated frameworks; (ii) methodological flexibility combined with robust comparability; (iii) broader stakeholder inclusivity, especially of cultural, media, and financial intermediaries; and (iv) coherent alignment between participatory approaches and governance scales. Addressing these priorities will significantly strengthen the legitimacy, efficiency, and scalability of participatory climate-risk governance in Europe and beyond, thereby fostering robust, adaptive governance systems capable of managing the complexities inherent in climate risk scenarios.