Experimental Investigation of Low-Carbon Concrete Using Biochar as Partial Cement Replacement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Research Objectives

- Characterise the physical properties of biochar and aggregates, including particle size, water absorption, and density.

- Develop and test concrete mixes incorporating different biochar replacement levels (0%, 5%, 15%, 30%, 45%, and 60%) and compare them with a control mix.

- Examine the fresh properties (workability and setting time) and hardened properties (compressive strength and dry density) of the mixes.

- Estimate the embodied carbon of each mix and assess the overall potential for carbon footprint reduction in biochar concrete.

1.3. Literature Review

1.3.1. Biochar Production and Its Properties

1.3.2. Impact of Biochar on Cement Hydration

1.3.3. Impact of Biochar on Properties of Fresh Concrete

1.3.4. Effect of Biochar on Properties of Hardened Concrete

1.3.5. Effect of Biochar on the Durability of Concrete

1.3.6. Effect of Biochar on the Internal Curing of Concrete

1.3.7. Use of Biochar for Internal Carbonation on Concrete

1.3.8. Use of Biochar on Concrete for Carbon Adsorption

1.3.9. Application of Biochar to Develop Low-Carbon Concrete

1.3.10. Summary

2. Methodology

2.1. Introduction

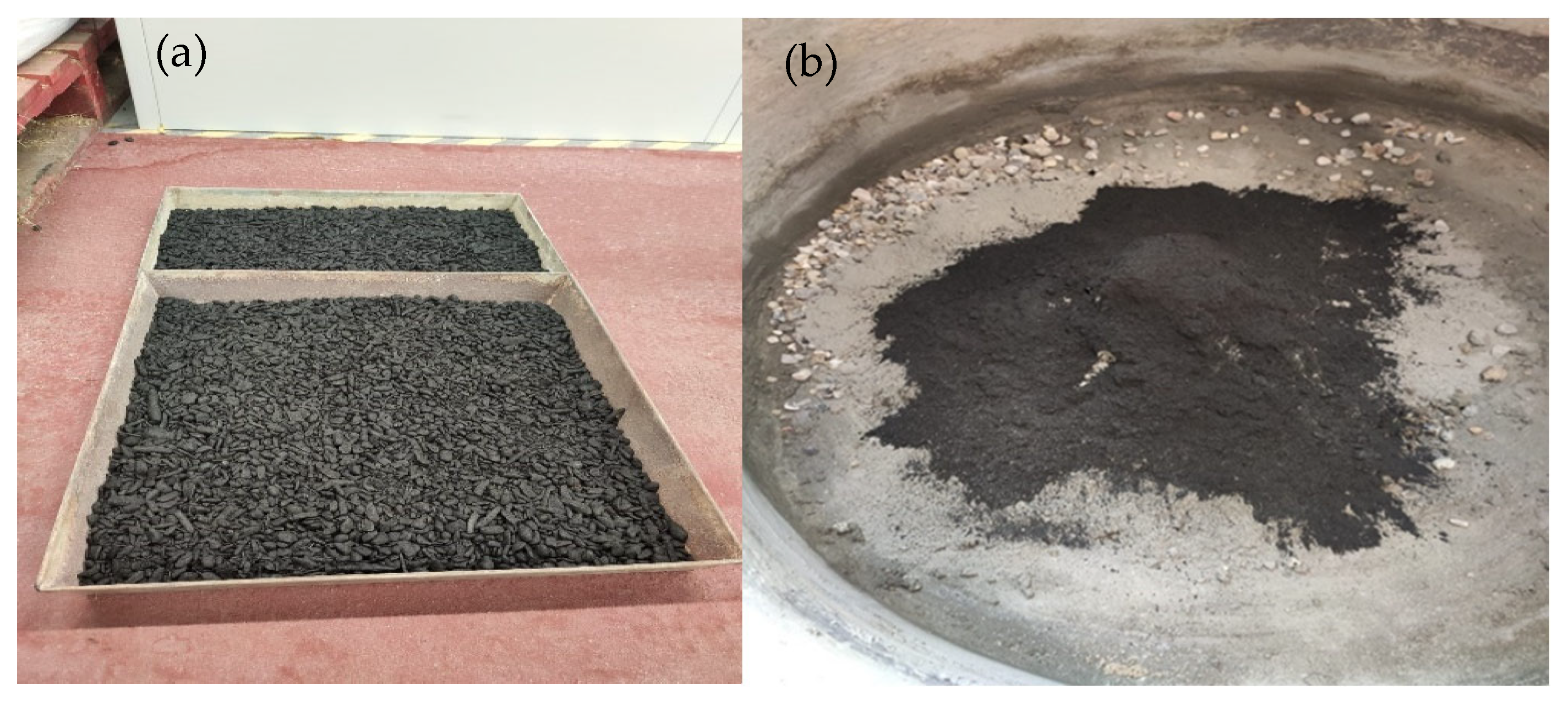

2.2. Materials and Their Characterisation Test

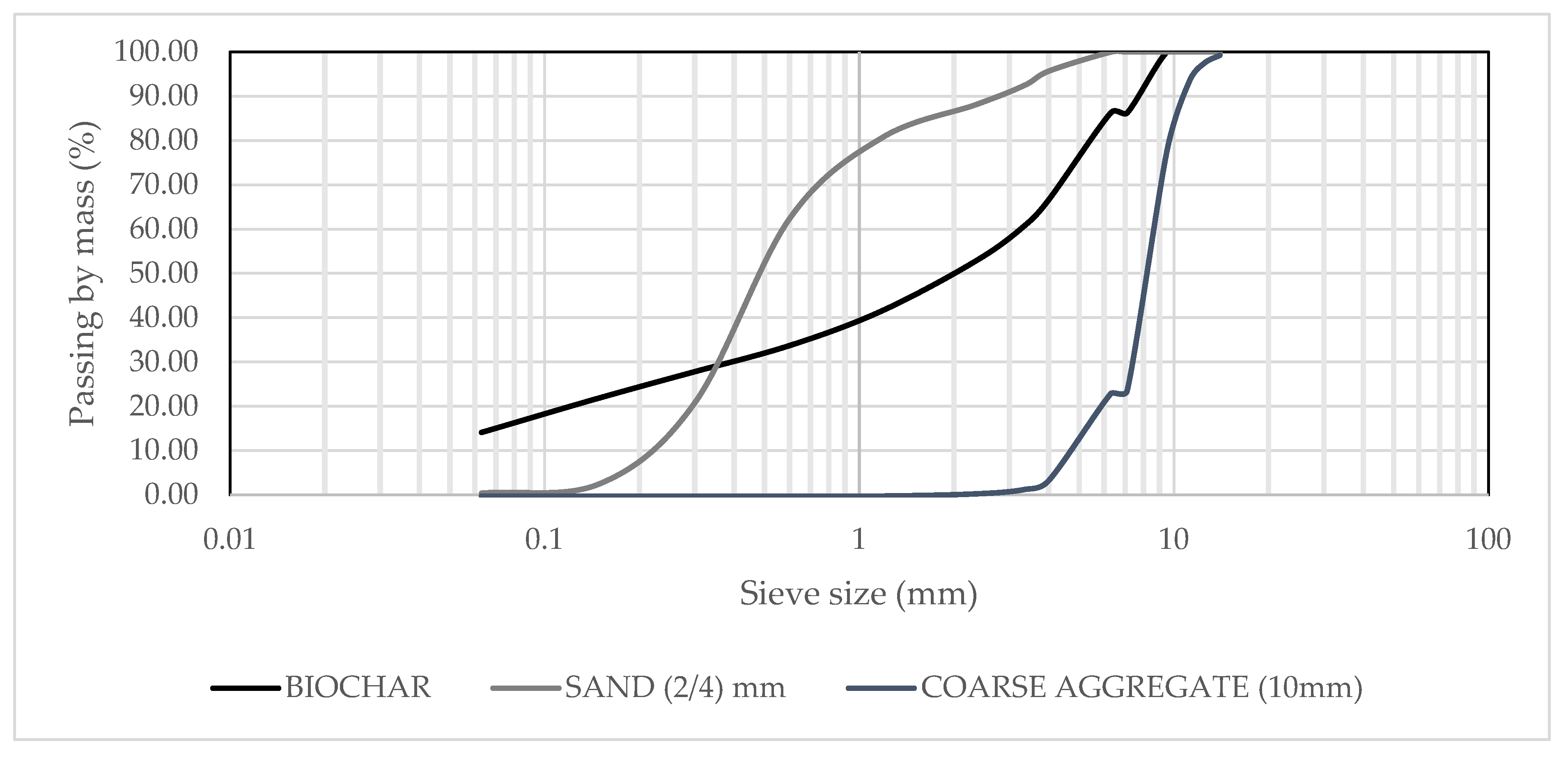

2.2.1. Sieve Analysis-Particle Size Distribution of Biochar and Aggregates

2.2.2. Determination of (Specific Gravity) and Water Absorption

2.3. Mix Design of Concrete

2.4. Fresh Concrete Properties

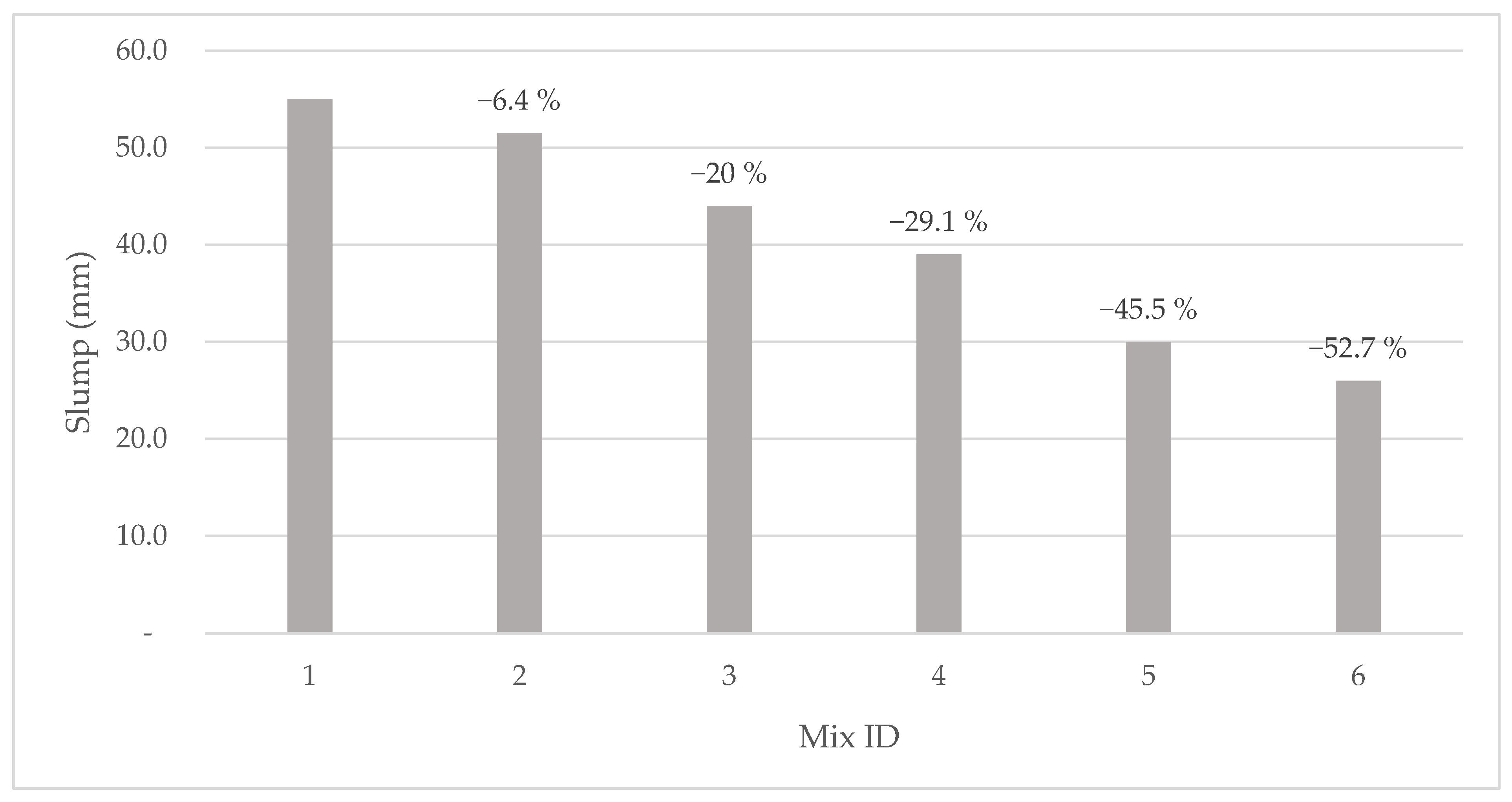

2.4.1. Slump Test

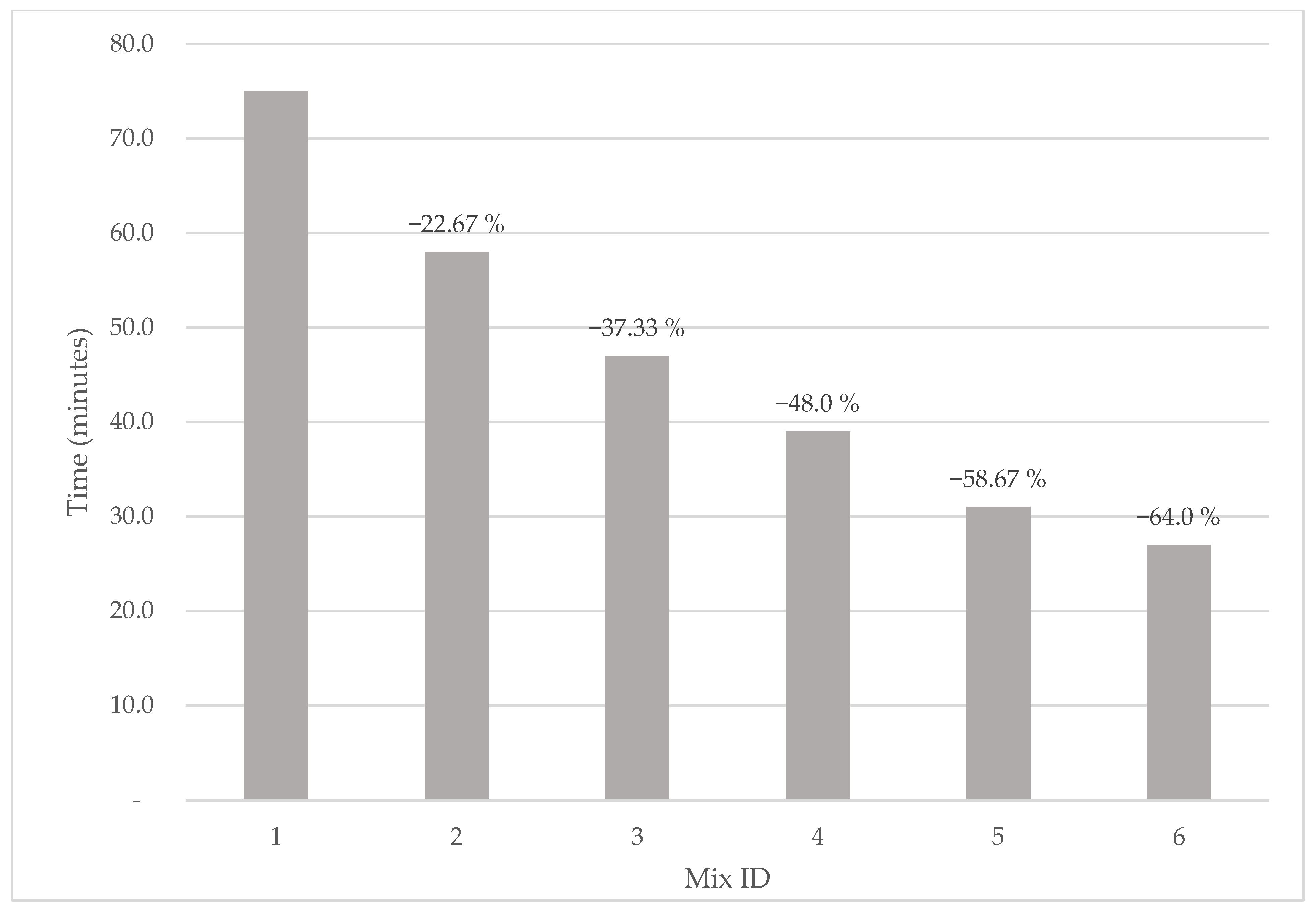

2.4.2. Initial Setting and Final Setting Time

2.5. Hardened Concrete Properties

2.5.1. Compressive Strength Test

2.5.2. Density

2.6. The Carbon Footprint of Concrete

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Size Distribution (PSD)

3.2. Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Water Absorption Value

3.3. Slump Test (Consistency of Concrete)

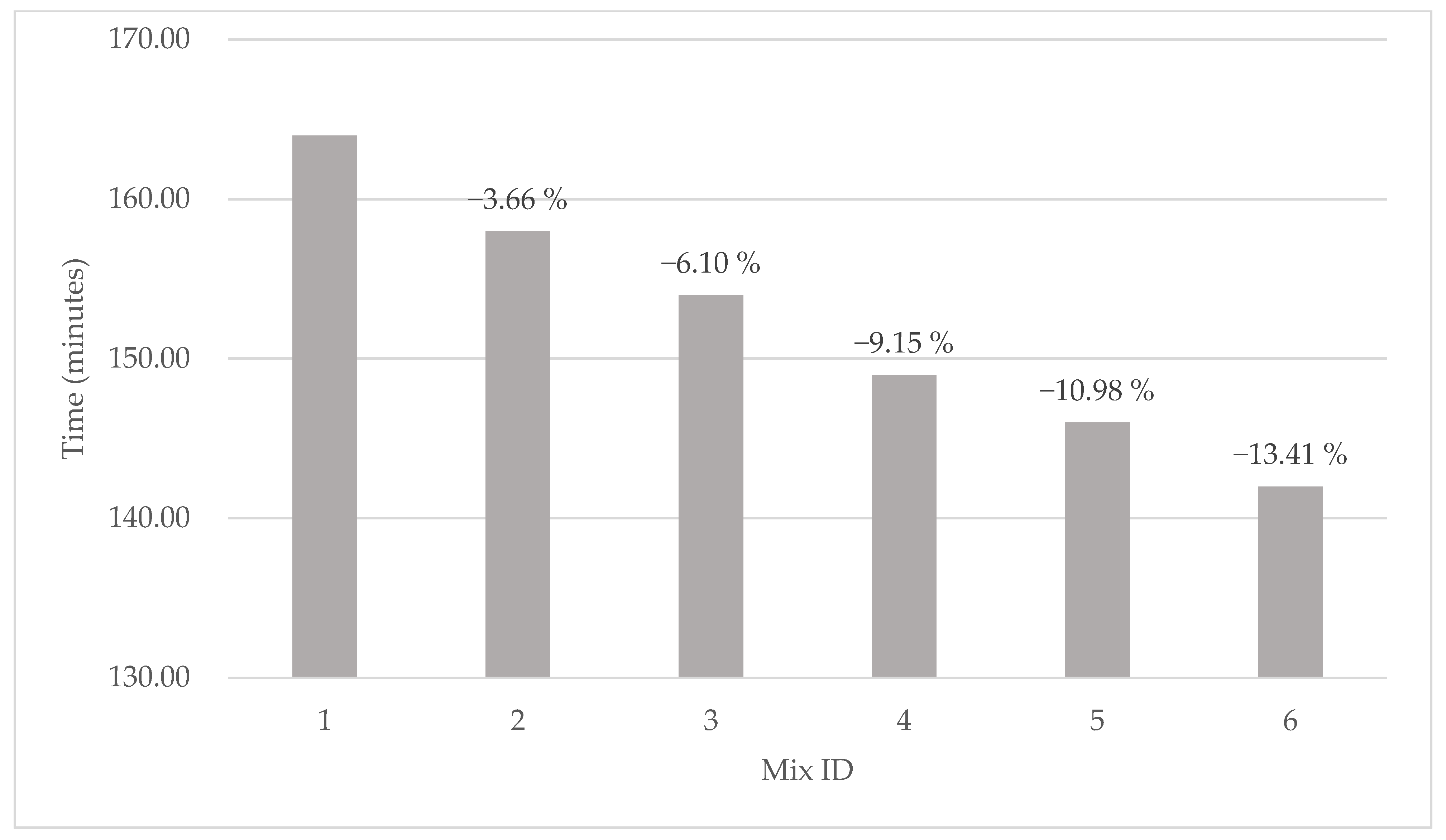

3.4. Initial Setting and Final Setting Time

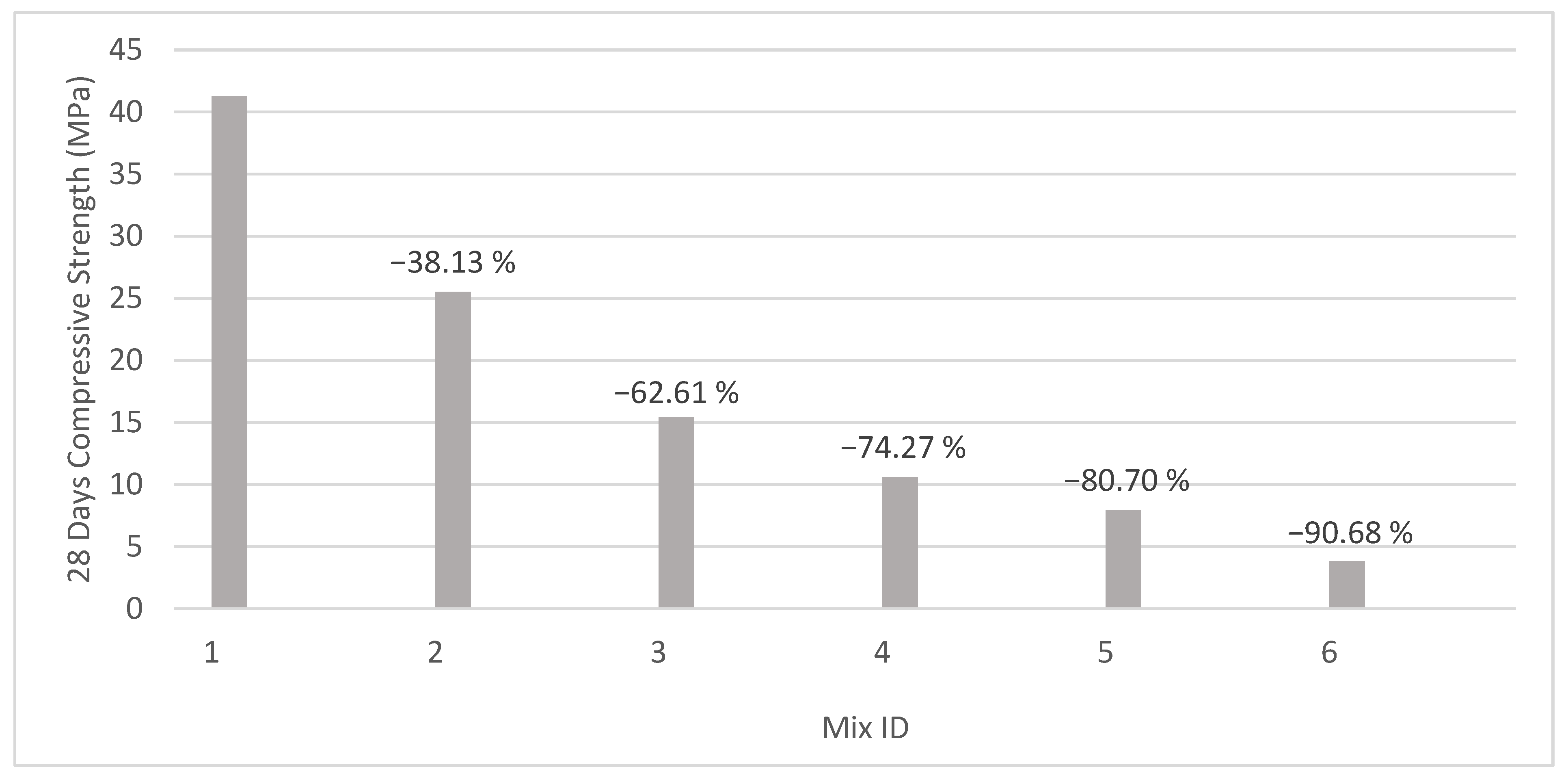

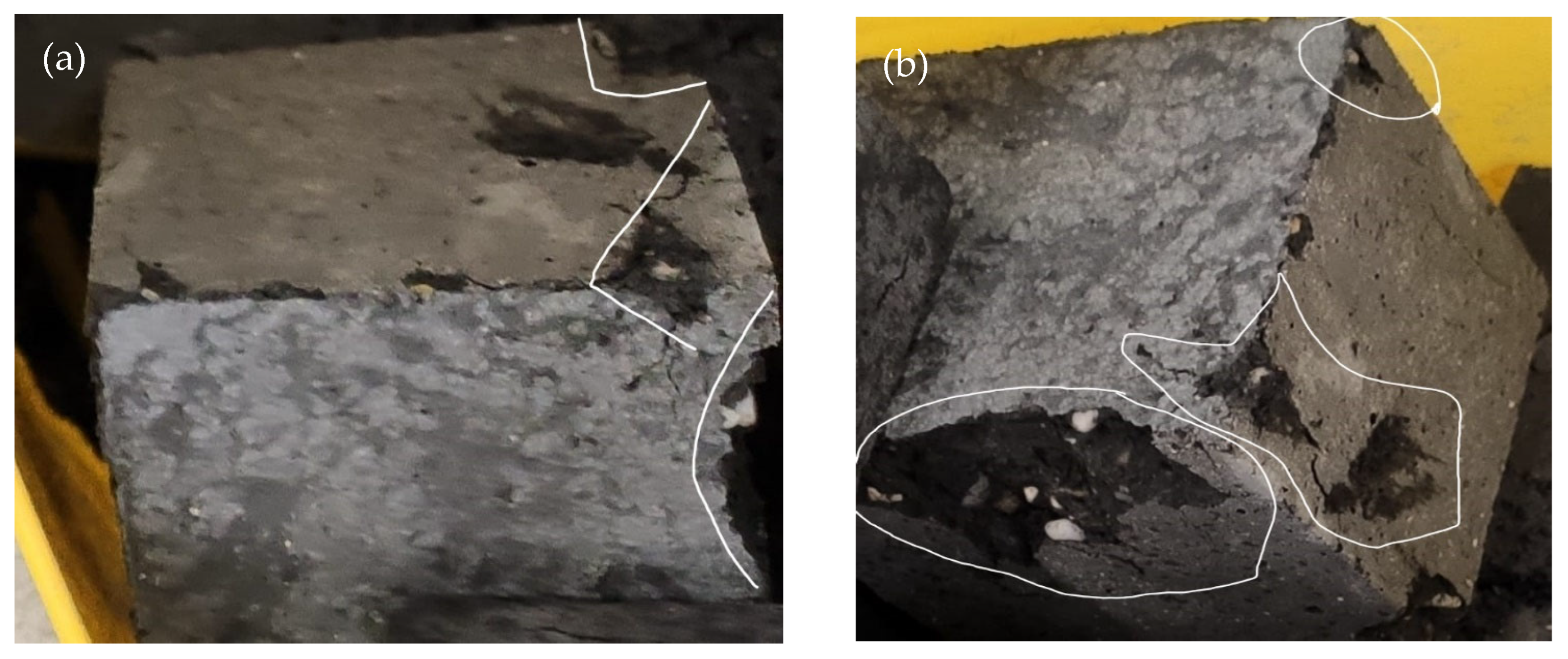

3.5. Compressive Strength

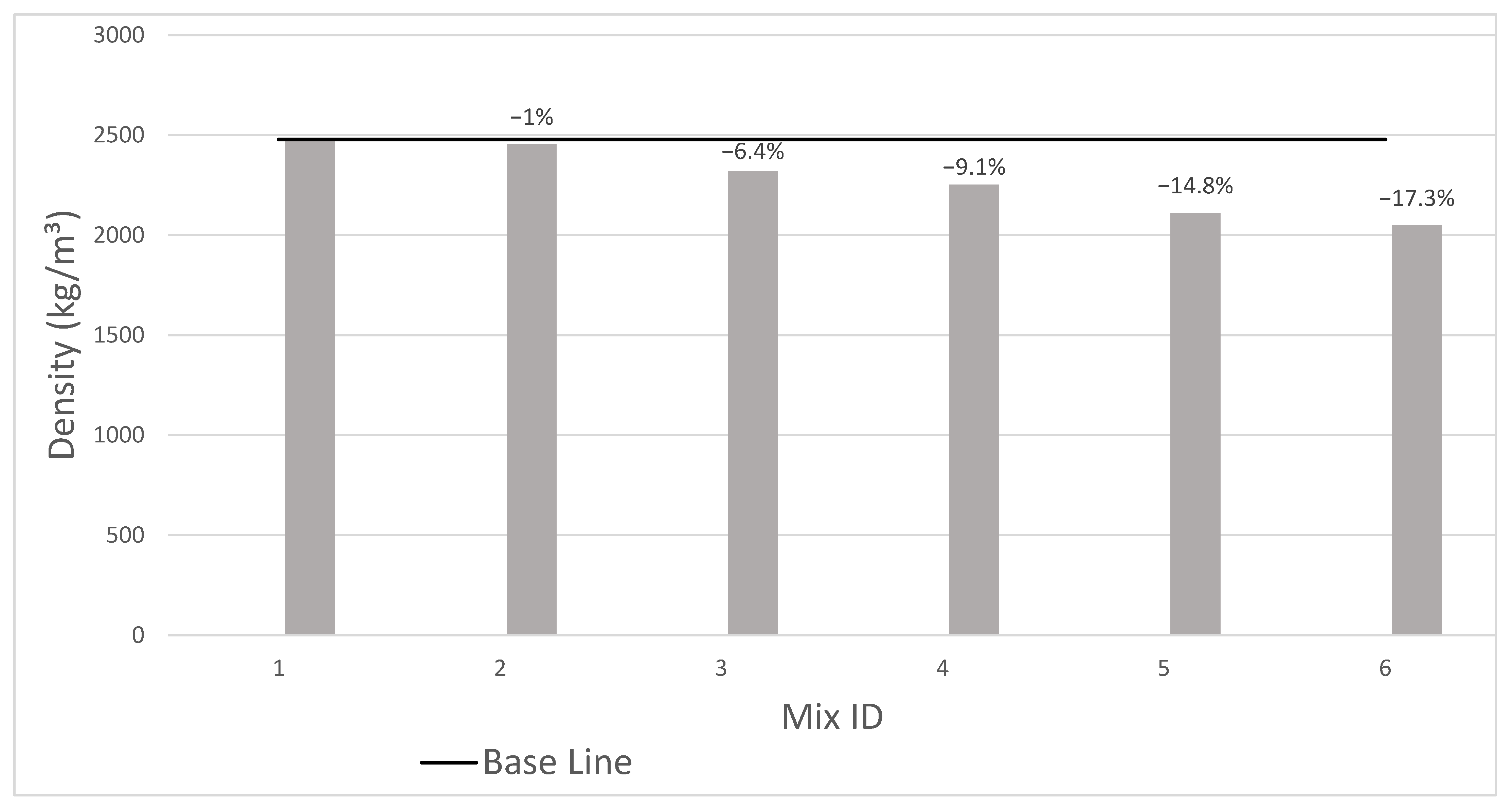

3.6. Density

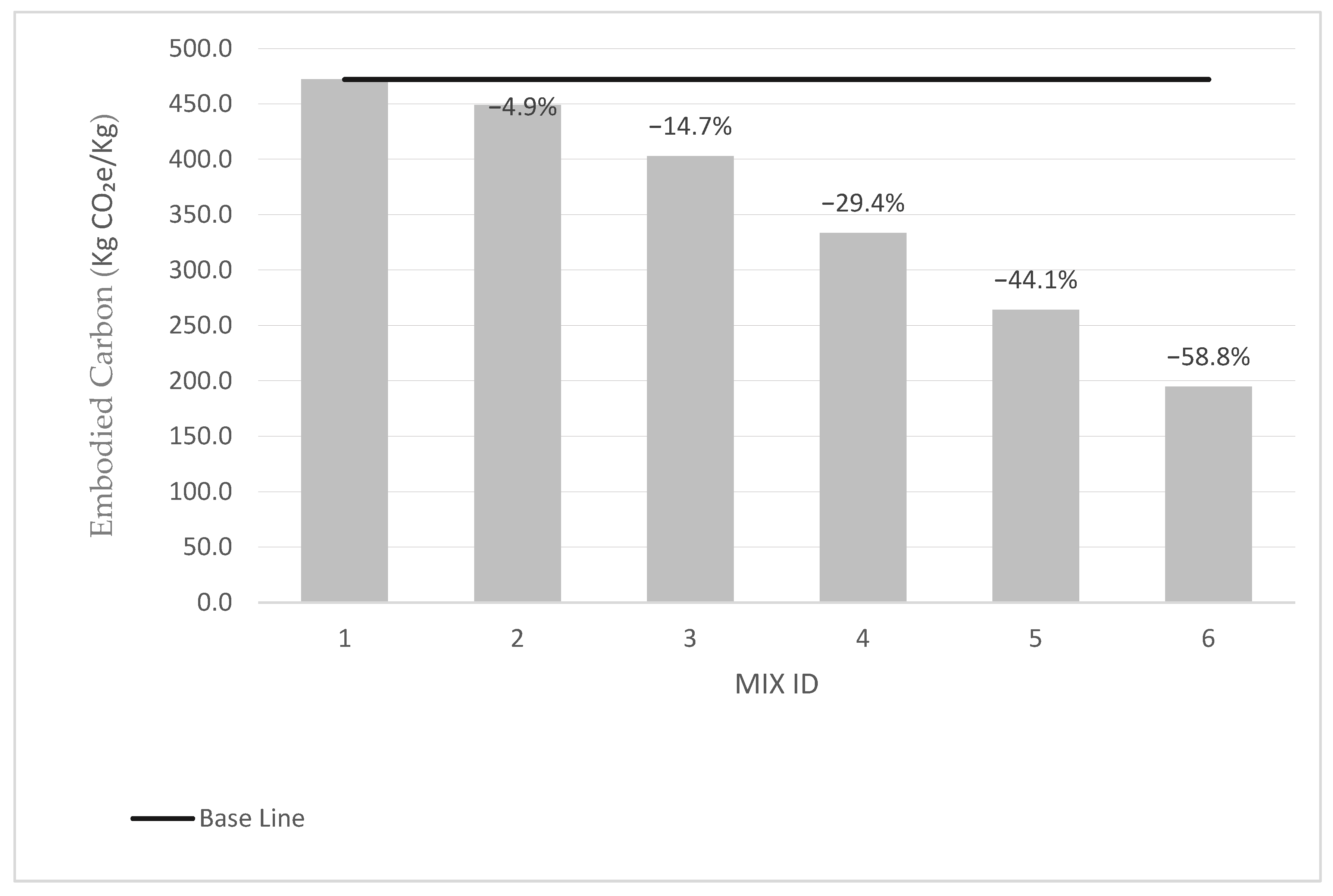

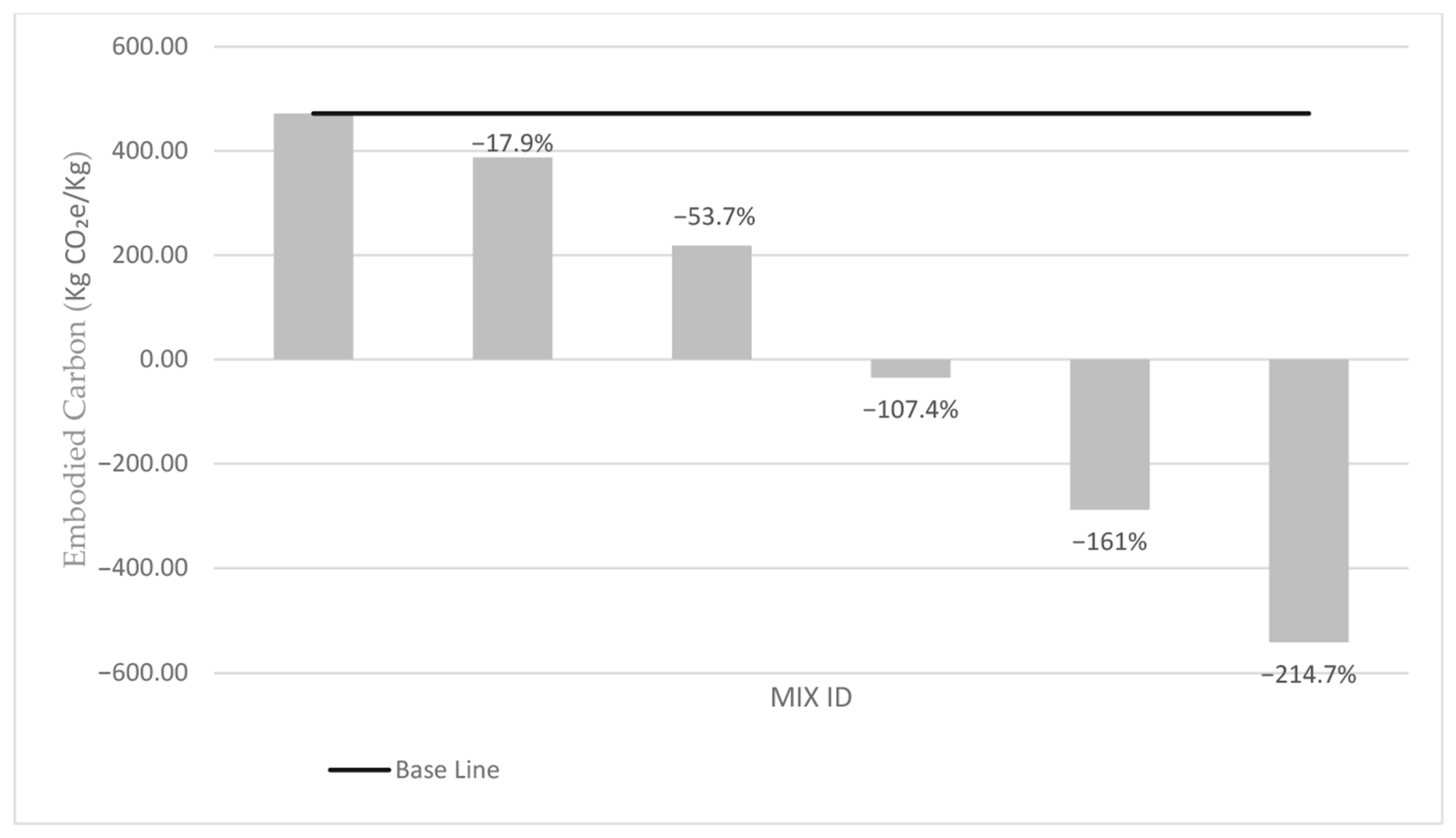

3.7. Carbon Footprint of Concrete

4. Conclusions

- Setting time: The incorporation of biochar accelerated the setting process. When cement was replaced with 60% biochar, the initial and final setting times decreased by 64% and 13.4%, respectively, compared to the control mix. At lower replacement levels (e.g., 5%), the variation was relatively minor, indicating that small additions (<5%) have a limited impact on workability time.

- Workability (Slump): Increasing biochar content led to a consistent reduction in slump value, with a 6.2% drop at 5% replacement and up to 52.7% at 60% replacement. This reduction is attributed to biochar’s high porosity and strong water absorption capacity, which reduces available mixing water.

- Compressive strength: A progressive decline in compressive strength was observed with increasing biochar content, with reductions of 38% at 5% and up to 90% at 60% replacement. The high-water absorption of biochar and its inert nature contribute to this loss of strength. Hence, higher replacement levels are not suitable for structural applications.

- Density: The density of concrete decreased proportionally with biochar addition due to the low specific gravity of biochar. A reduction ranging from 1% (at 5%) to 17.3% (at 60%) was observed.

- Embodied carbon: A significant reduction in embodied carbon was achieved, reaching up to 58.8% at 60% replacement (without accounting for carbon sequestration). When biochar’s carbon offset value was considered, mixes containing ≥ 30% biochar demonstrated a net carbon-negative footprint.

5. Recommendations for Further Studies

- Based on the physical characteristics of the hardwood biochar used in this study (high porosity, fine particle size, and low density), it is unlikely to be suitable as a partial replacement for coarse aggregates in structural concrete, which require materials with substantially higher strength and density.

- Biochar’s high-water absorption (217% in 24 h) reduces mix workability; hence, it should be used in a saturated surface dry (SSD) condition or with suitable admixtures.

- Dry grinding of the oven-dried biochar produced significant airborne dust during preparation. Wet grinding, followed by re-drying, is therefore recommended to reduce dust emissions and improve handling safety.

- Due to its low specific gravity, biochar tends to segregate during vibration; therefore, gentle compaction methods should be adopted.

- Further studies should include standardized carbon absorption tests to validate biochar’s CO2 sequestration capacity and establish quantitative models for embodied carbon reduction.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moon, D.H.; Park, S.S.; Kang, S.-P.; Lee, W.; Park, K.T.; Chun, D.H.; Rhim, G.B.; Hwang, S.-M.; Youn, M.H.; Jeong, S.K. Determination of kinetic factors of CO2 mineralization reaction for reducing CO2 emissions in cement industry and verification using CFD modelling. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. UK’s Path to Net Zero Set Out in Landmark Strategy. GOV.UK, 19 October 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uks-path-to-net-zero-set-out-in-landmark-strategy (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Ma, B.; Zhu, X.; Ok, Y.S.; Mechtcherine, V.; Tsang, D.C.W. Biochar as construction materials for achieving carbon neutrality. Biochar 2022, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.; Steiner, C.; Downie, A.; Lehmann, J. Biochar effects on nutrient leaching. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology; Lehmann, J., Joseph, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Chapter 7. Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass for Energy and Fuels; RSC Energy and Environment Series; Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 146–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Review of fast pyrolysis of biomass and product upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, A.; Crosky, A.; Munroe, P. Physical Properties of Biochar. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology; Lehmann, J., Joseph, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lua, A.C.; Yang, T.; Guo, J. Effects of pyrolysis conditions on the properties of activated carbons prepared from pistachio-nut shells. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2004, 72, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, W.A.W.A.K.; Mohd, A.; da Silva, G.; Bachmann, R.T.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Rashid, U.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H. Biochar production from waste rubber-wood-sawdust and its potential use in C sequestration: Chemical and physical characterization. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 44, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W.; Pang, S.D. Biochar-mortar composite: Manufacturing, evaluation of physical properties and economic viability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Sarmah, A.K. Novel biochar-concrete composites: Manufacturing, characterization and evaluation of the mechanical properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W.; Cynthia, S.Y.T. Use of biochar-coated polypropylene fibres for carbon sequestration and physical improvement of mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 83, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berodier, E.; Scrivener, K. Understanding the filler effect on the nucleation and growth of C-S-H. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 3764–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidabadi, Z.A.; Bakhtiari, S.; Abbaslou, H.; Ghanizadeh, A.R. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of biochar from agricultural waste biomass for use in building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 181, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.; Cyr, M.; Ringot, E. Mineral admixtures in mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, K.L.; Crumbie, A.K.; Laugesen, P. The interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) between cement paste and aggregate in concrete. Interface Sci. 2004, 12, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, P.; Restrepo-Baena, O.; Tobón, J.I. Microstructural analysis of interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and its impact on the compressive strength of lightweight concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 137, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, R.; Chehab, G. Mechanical and Microstructure Properties of Biochar-Based Mortar: An Internal Curing Agent for PCC. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Gupta, S.; Pang, S.D.; Kua, H.W. Waste Valorization using biochar for cement replacement and internal curing in ultra-high performance concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W. Carbonaceous micro-filler for cement: Effect of particle size and dosage of biochar on fresh and hardened properties of cement mortar. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 662, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Ahmad, S.; Restuccia, L.; Spoto, C.; Jagdale, P.; Tulliani, J.-M.; Ferro, G.A. Carbonized nano/microparticles for enhanced mechanical properties and electromagnetic interference shielding of cementitious materials. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2016, 10, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, L.; Ferro, G.A. Promising low cost carbon-based materials to improve strength and toughness in cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 126, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Pang, X.; Tan, K.; Bao, T. Evaluation of pervious concrete performance with pulverized biochar as cement replacement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 119, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, J.; Holm, N.; Chen, F. Mini-chunk biochar supercapacitors. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2014, 44, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-H.; Li, H. Pore structure and chloride permeability of concrete containing nano-particles for pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Holm, N.; Rajagopalan, K.; Chen, F.; Ma, S. Highly ordered microporous woody biochar with ultra-high carbon content as supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 113, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Lehmann, J. Biochar pH, electrical conductivity and liming potential. In Biochar: A Guide to Analytical Methods; Singh, B., Camps-Arbestain, M., Lehmann, J., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Chen, Y. Supercapacitor devices based on graphene materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 13103–13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabhi, R.S.; Kirk, D.W.; Jia, C.Q. Preliminary investigation of electrical conductivity of monolithic biochar. Carbon 2017, 116, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Wyrzykowski, M.; Tang, C.; Lehmann, E. Internal curing with lightweight aggregate produced from biomass-derived waste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 59, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Keiser, L.; Golias, M.; Weiss, J. Absorption and desorption properties of fine lightweight aggregate for application to internally cured concrete mixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wu, X.; Tan, K.; Zou, Z. Effect of Biochar Dosage and Fineness on Concrete Mechanical Properties and Durability of Concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Tsang, D.C.; Guo, B.; Yang, J.; Shen, Z.; Hou, D.; Ok, Y.S.; Poon, C.S. Biochar as green additives in cement-based composites with carbon dioxide curing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.-Y.; Chaney, R.C. Introduction to Environmental Geo Technology; CRC Press eBooks; CRC Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamdad, H.; Hawboldt, K.; MacQuarrie, S.; Papari, S. Application of biochar for acid gas removal: Experimental and statistical analysis using CO2. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 10902–10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, A.E.; Gao, B.; Zhang, M. Carbon dioxide capture using biochar produced from sugarcane bagasse and hickory wood. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 249, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, P.D.; You, S.; Igalavithana, A.D.; Xia, Y.; Bhatnagar, A.; Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W.; Kim, S.; Kwon, J.-H.; Tsang, D.C.; et al. Biochar-based adsorbents for carbon dioxide capture: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahijani, P.; Mohammadi, M.; Mohamed, A.R. Metal incorporated biochar as a potential adsorbent for high capacity CO2 capture at ambient condition. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 26, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ruan, S.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Mechtcherine, V.; Tsang, D.C. Biochar-augmented carbon-negative concrete. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Dong, W.; Castel, A.; Wang, K. Biochar-cement concrete toward decarbonization and sustainability for construction: Characteristic, performance and perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.I.; Khan, R.I.; Ashraf, W.; Pendse, H. Production of sustainable, low-permeable and self-sensing cementitious composites using biochar. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 28, e00279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Biochar Foundation (EBC). European Biochar Certificate—Guidelines for a Sustainable Production of Biochar, Version 10.1; European Biochar Foundation (EBC): Arbaz, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.european-biochar.org/en/download (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- BS EN 12620:2013; Aggregates for Concrete. BSI Standards Limited: London, UK, 2013.

- BS EN 933-1; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates. Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. Sieving Method. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2012.

- BS EN 1097-6; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates. Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2022.

- Design of Normal Concrete Mixes, 2nd ed.; Department of the Environment, Building Research Establishment: Garston, UK, 1992.

- BS EN 12350-2; Testing Fresh Concrete. Slump Test. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2009.

- BS EN 196-3; Methods of Testing Cement. Determination of Setting Times and Soundness. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2016.

- BS EN 197-1:2011; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2011.

- BS EN 12390-3; Testing Hardened Concrete. Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2019.

- BS EN 12350-6; Testing Fresh Concrete. Density. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2019.

- Gibbons, O.P.; Orr, J.J.; Archer Jones, C.; Arnold, W.; Green, C. How to Calculate Embodied Carbon, 2nd ed.; Institution of Structural Engineers (IStructE): London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kanavaris, F.; Gibbons, O.; Walport, E.; Shearer, E.; Abbas, A.; Orr, J.; Marsh, B. Reducing embodied carbon dioxide of structural concrete with lightweight aggregate. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Eng. Sustain. 2022, 175, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Mahadevan, M.; Prajapati, S.; Ayati, B.; Kanavaris, F. Development of low-carbon lightweight concrete using pumice as aggregate and cement replacement. In Proceedings of the RILEM International Conference on Synergising Expertise Towards Sustainability and Robustness of Cement-Based Materials and Concrete Structures (SynerCrete’23), Milos, Greece, 14–16 June 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Biomass | Temperature | Size of Particles | Relative Density | Carbon Percentage | Absorption Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Biochar as Wood sawdust | 300 °C | 3–200 Micrometer | 1.59 | 62.3% | 736% |

| 500 °C | 1.51 | 87.2% | 879% | |||

| [11] | Biochar as a Paper sludge | 500 °C | Not available | Not available | 30.0% | Not available |

| [12] | Biochar as Wood sawdust | 300 °C | 3 to 200 Micrometer | 1.54 | 68.3% | 246% |

| Reference | Biochar Type | Application | Biochar Percentage | Major Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | Biochar from Rice husk | Used as Cement replacement in mortar | Less or equal to 10% weight of cement | The increase in strength by 5% can be attributed to the pozzolanic activity of biochar, while a decrease in strength by 10% may be due to the dilution of cement. |

| [19] | Biochar from Wood dust | Used in UHPC as partial cement. replacement | Less or equal to 8% by wt. of cement replacement | Hydration level increased; compressive strength decreased by 8–15% for coarser biochar. |

| [21] | Biochar from Nuts shell | Used as a Supplement/additive in mortar | Less or equal to 1% of the weight of cement | Fracture energy increased by ~25–30% developed concrete with enhanced electromagnetic shielding effectiveness (up to 15 dB improvement). |

| [23] | Biochar from Plywood (Eucalyptus) | Used in a previous Concrete as a Cement replacement | Less or equal to 6.5% replacement by wt. | Compressive & splitting tensile strength increased—up to ~33% at 6.5% replacement; porosity/permeability maintained |

| Mix ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg/m3 | Control Mix (0% Cement Replacement) | 5% Cement Replacement | 15% Cement Replacement | 30% Cement Replacement | 45% Cement Replacement | 60% Cement Replacement |

| Cement | 507 | 481.7 | 431.0 | 354.9 | 278.9 | 202.8 |

| Biochar | 0 | 25.4 | 76.1 | 152.1 | 228.2 | 304.2 |

| Sand | 692 | 692 | 692 | 692 | 692 | 692 |

| Coarse aggregates | 918 | 918 | 918 | 918 | 918 | 918 |

| w/c | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| admixtures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, A.A.; Thapa, S.J. Experimental Investigation of Low-Carbon Concrete Using Biochar as Partial Cement Replacement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310744

Abbas AA, Thapa SJ. Experimental Investigation of Low-Carbon Concrete Using Biochar as Partial Cement Replacement. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310744

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Ali A., and Sagar J. Thapa. 2025. "Experimental Investigation of Low-Carbon Concrete Using Biochar as Partial Cement Replacement" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310744

APA StyleAbbas, A. A., & Thapa, S. J. (2025). Experimental Investigation of Low-Carbon Concrete Using Biochar as Partial Cement Replacement. Sustainability, 17(23), 10744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310744