Abstract

As cities grow denser, renewing old communities has become vital to improving urban functions and achieving high-quality development. However, institutional, economic, social, and technical factors intertwine, constraining the renewal process and limiting its effectiveness. Therefore, this study aims to identify and analyze the barriers to the Renewal of Old Residential Communities (RORCs). Twenty-eight barriers were identified through a literature review, questionnaires, and face-to-face interviews with community residents and professionals involved in RORCs. Based on the statistical results of 183 valid survey responses, this study identified the top five barriers to RORCs as follows: insufficient renewal funding, divergent resident demands and opinions, conflicts of interest among stakeholders, high renewal costs, and complex property rights. The 28 barriers to RORCs were further extracted into seven latent factors based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA): (1) Policy and Planning Deficiencies, (2) Infrastructure and Historical Legacy Issues, (3) Resident Participation and Community, (4) Spatial and Physical Limitations, (5) Consensus Execution and Management Inadequacies, (6) Economic and Financial Constraints, and (7) Property Rights Complexity and Social Structure. Through an in-depth interpretation of these groups, this study enhances the understanding of the systemic barriers to RORCs and provides practical insights for policymakers and practitioners to prioritize interventions and formulate integrated, sustainable renewal strategies suited to high-density urban contexts.

1. Introduction

As urban spaces continue to densify and land resources grow increasingly scarce, urban renewal has become an urgent priority for enhancing urban functionality, improving residents’ living environments, and advancing high-quality urban development [1,2]. At the same time, old residential communities have increasingly exhibited pressing issues, including aging buildings, outdated infrastructure, insufficient public facilities, and declining environmental quality [3,4,5]. These problems are particularly pronounced in high-density urban areas, where limited land, complex property rights, and high population concentrations further heighten the need for timely renewal [6]. Consequently, identifying and addressing the barriers to renewing these communities is essential to guide effective interventions and support sustainable urban development.

However, unlike greenfield development on vacant land, the renewal of old residential communities (RORCs) occurs within a built environment shaped by complex historical contexts, entrenched interests, and multifaceted social relationships [7]. This renders the process fraught with challenges. RORCs are widely recognized as a complex and systematic undertaking, in which institutional, economic, social, and technical factors are deeply intertwined and mutually influential [8,9]. For instance, at the institutional level, the traditional top-down planning and management model often struggles to meet the refined governance demands of the renewal process [10]. At the economic level, there is a mismatch between the substantial funding required and the limited public financial input, while the participation incentives and profit models for private capital remain uncertain [11,12]. At the social level, the heterogeneity of residents leads to diverse needs and fragmented opinions, making consensus-building difficult [13]. Moreover, the complexity of property rights and the challenge of balancing interests among stakeholders further compound the core difficulties of community renewal [14]. These interrelated factors constrain one another, significantly undermining both the efficiency of the renewal process and the overall effectiveness of its outcomes. In some cases, they even result in project stagnation or suboptimal results that fall short of achieving the intended social, economic, and environmental benefits.

Previous research has examined barriers to urban renewal from multiple perspectives—including urban planning, public administration, sociology, and economics—providing valuable insights. For instance, Winston (2010), using Dublin as a case, identifies several obstacles to sustainable housing in urban regeneration, such as inadequate regulatory support, limited green-building expertise, and resistance to social mixing [15]. This single-city focus and fragmented approach limit engagement with the defining challenges of high-density districts, including spatial constraints and concentrated populations. Zhang et al. (2019) use Beijing’s Nanluoguxiang historic district as a case to identify key factors in urban regeneration, highlighting the central role of public-space improvement and building restoration, and providing a useful reference for this study [16]. However, their work focuses solely on a single type of historic district, identifies key regeneration factors, but does not examine the constraints from a “barrier” perspective, nor does it address the common challenges of high-density aging communities—such as spatial limitations, complex property rights, and divergent resident needs. Tsegay et al. (2023) focus on the core characteristic of “spatial constraints” in inner-city construction projects, emphasizing that urban sites are surrounded by existing buildings, dense residents, and busy streets, making space the most critical yet scarce resource [17]. Yet their analysis remains confined to site-level resource allocation during construction and does not address systemic constraints at the overall urban regeneration project level. Overall, existing studies have largely concentrated on identifying isolated barriers, with limited attention to their systemic interactions. In particular, research on the intrinsic relationships among different barrier, their relative importance (i.e., which are the key obstacles), and how they collectively form a systemic impediment remains limited. Moreover, relatively few studies have addressed the unique conditions of high-density urban environments, where spatial constraints, complex property rights, diverse resident needs, and multiple competing stakeholder interests amplify the challenges of renewal.

To address these gaps, this study aims to systematically identify and analyze the key barriers to the RORCs, with a particular focus on their interrelationships and relative importance in high-density urban contexts. Specifically, the study adopts a multi-step approach: first, a comprehensive literature review is conducted to compile a preliminary list of potential barriers; second, questionnaires and face-to-face interviews with community residents and professionals involved in the RORCs projects are used to validate and refine this list; third, EFA is applied to examine the underlying structure of the barriers, reduce dimensionality, and the barriers were further extracted into seven latent factors based on their interrelationships. By following this approach, the study seeks to provide a systematic framework for understanding the complex interactions among barriers, thereby offering guidance for more effective planning, policy, and intervention strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Renewal and Old Residential Communities

Urban renewal is understood as the process of transforming the urban fabric in a continuous and autonomous process [4]. Compared with greenfield development, renewal projects in existing residential communities involve renovation, reconstruction, or upgrading of aging infrastructure and housing stock within densely built environments [18]. Old residential communities often face multiple challenges, including deteriorating building structures, outdated infrastructure, insufficient public services, and declining environmental quality [13,19,20]. In high-density urban areas, these problems are further exacerbated by limited land availability, complex property ownership, and concentrated populations [6,21]. Existing studies emphasize that urban renewal is not merely a technical or construction issue; it is a complex, multi-dimensional process influenced by institutional, economic, social, and technical factors [8,9]. The literature indicates that understanding these factors and their interactions is essential for designing effective renewal strategies, particularly in high-density urban settings where constraints are more pronounced.

2.2. Barriers to the RORCs

The RORCs are affected by multiple interrelated factors, which together constrain the effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability of renewal projects, particularly in high-density urban areas. In terms of governance and planning, traditional top-down management models often fail to respond to the diverse needs of residents and the complex dynamics among multiple stakeholders [22]. Policy gaps, fragmented coordination, and inconsistent regulations can lead to delays, conflicts, or suboptimal decision-making [1,3,11,23]. In high-density areas, aligning the interests of multiple governmental departments, developers, and resident committees is especially challenging, often causing delays or suboptimal decisions [8,9]. Regarding financial and economic aspects, insufficient public funding, high renovation costs, uncertain investment returns, and limited incentives for private capital hinder project implementation [11,13,24,25]. Economic challenges are often compounded by disputes over property rights or disagreements on resident compensation, making it difficult to mobilize necessary resources [14,26].

From the social perspective, the heterogeneity of residents results in diverse demands and opinions, complicating consensus-building [13]. Low participation and limited trust between residents and project implementers further impede progress [6,27]. In high-density areas, these social complexities are amplified due to larger populations and intricate stakeholder networks [8,9]. However, existing studies have largely concentrated on identifying isolated barriers, such as public resistance or stakeholder conflicts, often overlooking how these barriers interrelate and form a more comprehensive set of challenges. The systemic interactions between social factors, such as the influence of diverse resident needs, trust issues, and participation levels, remain insufficiently explored.

Finally, in terms of technical and operational conditions, aging infrastructure, insufficient construction technologies suitable for dense sites, limited management capacity, and low standardization in design and construction practices all affect project efficiency, increase costs, and compromise safety and quality [1,10,13,19,20,28,29,30,31]. These technical barriers, when considered in isolation, fail to account for how they interact with social and governance barriers in high-density urban environments. The pressure exerted by spatial constraints, complex property rights, diverse resident needs, and multiple competing stakeholder interests makes the identification and resolution of these barriers even more challenging. This gap in the literature highlights the need for more comprehensive studies that address how these various factors interact systematically, particularly in high-density urban contexts.

Many studies treat these barriers as isolated or general challenges and fail to adequately explore their distinctiveness and exacerbated effects in high-density environments. For instance, spatial and physical constraints such as insufficient public facilities, limited construction sites, and a lack of green space or public areas are frequently mentioned in the literature. However, these issues are often overlooked as a focal point of research. They are rarely considered as a core, decisive group of barriers that fundamentally restrict the feasibility of urban renewal in high-density contexts. In such areas, the pressure on space, infrastructure, and public resources is far more intense, making these challenges not only more acute but also more complex to address [6,32].

Collectively, these factors interact in complex ways, creating systemic constraints that make RORCs challenging. While previous studies have identified many individual barriers, their interrelationships, relative importance, and implications in high-density urban environments remain insufficiently explored. This highlights the need for a systematic approach to identify and analyze the key barriers affecting renewal projects.

3. Methodology

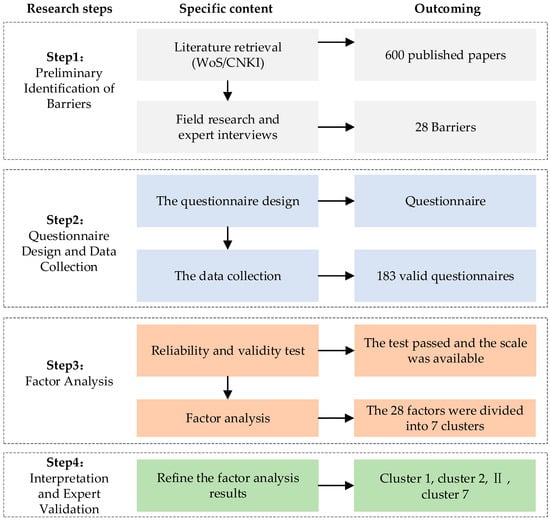

This study followed a four-step research framework to identify and analyze the barriers to RORCs in high-density urban areas. The methodological process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework for the study.

3.1. Preliminary Identification of Barriers

This study begins with a comprehensive literature review to preliminarily identify barriers to RORCs. A literature search was conducted in the Web of Science (WoS) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases, covering the period from 1 March 2005 to 1 March 2025. The following keywords were used:

(“old residential” OR “existing residential” OR “housing estate”) AND (“renewal” OR “renovation” OR “regeneration” OR “retrofit”).

This search initially retrieved 1639 publications from WoS and 2181 from CNKI, totaling 3820 papers. To ensure relevance, only journal articles and reviews were retained, while publications in unrelated disciplines—such as geography, physics, chemistry, and agriculture—were excluded. After this filtering, 911 papers from WoS and 105 authoritative core journal papers from CNKI remained, totaling 1016 publications. Further refinement focused on studies directly related to urban renewal and renovation, excluding works primarily concerned with cost-effectiveness, building efficiency, or mechanical performance. Through detailed full-text screening, 600 highly relevant studies were ultimately selected for in-depth analysis. Following this, a literature analysis was performed to identify the barriers to RORCs in High-Density Urban Areas. Finally, the identified barriers were validated for their rationality and comprehensiveness through field surveys in densely populated urban communities and in-depth interviews with five industry experts. These experts were drawn from companies including Qingdao Haiming Urban Development Co., Ltd., Henan Urban Renewal Construction Co., Ltd., and Zhengzhou Urban Development and Investment Co., Ltd., with over 10 years of professional experience in urban renewal. This selection ensured that the validation process captured both theoretical insights and practical considerations from experienced practitioners. Drawing on these findings, the initially extracted barriers were refined, yielding a preliminary list of 28 barriers, presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of preliminary barriers.

3.2. Questionnaire and Data Collection

A structured questionnaire was designed to collect data for this study. It comprised three main sections: (1) Preface, which outlined the primary objectives of the survey and provided a brief explanation of relevant concepts and terminology related to the RORCs, ensuring that respondents clearly understood the survey content; (2) Respondents’ information, including key information relevant to the study such as occupational category, educational background, and years of professional experience; and (3) Assessment of barriers, in which the 28 preliminarily identified barriers were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale to measure their perceived impact on the RORCs, ranging from 1 (“little to no impact”) to 5 (“very high impact”). To ensure the validity and reliability of the data, the majority of questionnaires were distributed directly by the research team via face-to-face interviews, WeChat, Email, and a professional online survey platform (www.wjx.cn) to community residents, property/community managers, urban renewal practitioners, and scholars, while a small portion was further disseminated by respondents themselves. However, as some respondents may provide careless, haphazard, or random answers, the quality of the data could be compromised [47]. Therefore, the questionnaires were excluded under either of the following conditions: ① the respondent answered each item in less than 60 s; or ② the respondent provided a string of identical responses equal to or exceeding half the total number of items on the scale [48]. In total, 260 questionnaires were distributed, and 183 valid responses were collected after applying these exclusion criteria. Specifically, 53 responses were excluded due to short completion times, and 24 responses were excluded for identical answer patterns. After applying these screening rules, the average completion time for the valid responses was 274 s, and the median completion time was 176 s. The valid responses came from a wide geographic range, covering 46 cities across China, including Beijing, Qingdao, Jinan, Dalian, Yantai, Changsha, Hangzhou, Shanghai, and others. This extensive coverage ensures a diverse representation of perspectives from different urban contexts. These values reflect an appropriate amount of time for participants to thoughtfully consider their answers. Detailed information about the respondents is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Respondent information.

3.3. Data Analysis Method

Factor analysis is a widely used statistical technique for reducing complex datasets by uncovering the underlying structures among a large set of observed, correlated variables. By condensing these variables into a smaller number of latent factors, the method allows researchers to identify latent factors of related barriers and create a more interpretable framework [49]. In this study, factor analysis was conducted using SPSS 27.0 to examine the interrelationships among the key barriers to old residential community renewal in high-density urban areas.

Crucially, EFA was employed rather than confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). EFA is particularly suitable when the underlying factor structure has not been theoretically established, and the goal is to uncover potential latent dimensions in a data-driven manner [50]. Since the literature on RORCs does not provide a validated or widely accepted model specifying how these barriers should be organized into constructs, imposing a predefined structure through CFA would be inappropriate at this stage. EFA therefore offers a more rigorous and methodologically sound approach for identifying the dimensionality of the barriers. This approach not only simplifies data complexity but also reveals underlying patterns among multiple barriers, providing a systematic basis for prioritizing and addressing the most critical obstacles in community renewal projects.

To ensure the rigor and credibility of the study, reliability and validity tests were conducted on the survey data. Reliability testing evaluates the consistency of the measurement instrument, indicating whether the survey items produce stable and reproducible results across different respondents or repeated measurements. For the reliability analysis of the questionnaire, reliability is primarily assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) reliability coefficient [51]. A higher CA value indicates stronger internal consistency among the items, suggesting that the construct measured by the scale is more coherent and that the resulting evaluation is more reliable. According to established criteria [52], a CA value between 0.5 and 0.7 indicates acceptable reliability, between 0.7 and 0.9 indicates high reliability, and above 0.9 indicates excellent reliability. Validity is primarily evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index, which should be at least 0.5. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.05) is conducted to verify whether the data are suitable for factor analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

- (1)

- Reliability Test

In this study, IBM SPSS 27.0 was used to conduct the reliability analysis of the scale data. The overall CA value of the scale was 0.915, and the CA value based on standardized items was 0.916. Both values exceed 0.9, indicating a high level of internal consistency within the scale, shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reliability test results.

To examine the effect of each factor on the overall reliability, this study adopted a stepwise deletion approach, in which one factor was removed at a time and the CA value was recalculated. The results show that when any single factor is deleted, the CA coefficients of the remaining items ranged from 0.912 to 0.915, indicating that all factors contribute positively to the overall reliability and should be retained, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Factor CA value after removing itself.

- (2)

- Validity test

The KMO value of the measurement scale for barriers to RORCs in high-density urban areas is 0.854 (Table 5), indicating good sampling adequacy. The Approximate Chi-square value from Bartlett’s test of sphericity is 2576.183 (p = 0.000 < 0.001), suggesting that the scale is appropriate for factor analysis. This result shows that the correlation coefficient matrix significantly differs from the identity matrix, implying sufficient correlations among the variables.

Table 5.

KMO and Bartlett test.

4.2. Ranking and Factor Analysis of Barriers

4.2.1. Ranking Barriers

The analysis of the survey responses identified a clear and statistically significant hierarchy of perceived barriers to urban renewal. The mean scores, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals for all 28 barriers are presented in Table 6. The five barriers with the highest mean scores were (1) Insufficient renewal funding (M = 4.16), (2) Divergent resident demands and opinions (M = 4.09), (3) Conflicts of interest among stakeholders (M = 4.05), (4) High renewal costs (M = 3.94), and (5) Complex property rights (M = 3.87). These barriers were selected based on their significantly higher mean scores, reflecting the most pressing challenges in the renewal of old residential communities in high-density urban areas.

Table 6.

Significance-Based Ranking of Urban Renewal Barriers, with Descriptive Statistics and Friedman Test Results.

The selection of these five barriers, rather than four or six, is driven by the clear statistical hierarchy in the data, where these five were consistently ranked the highest. The corresponding confidence intervals and standard deviations further reinforce this selection, indicating that the ranking is not due to random variation. For instance, insufficient renewal funding (ranked first) had the highest mean score (M = 4.16) and a narrow confidence interval ([4.03, 4.30]), signifying that this is a consistently significant barrier across respondents. Similarly, divergent resident demands and opinions (ranked second) with a mean of 4.09 and a confidence interval of [3.96, 4.21] underscore the widespread difficulty in aligning the needs of diverse residents. The Friedman test confirmed that the differences in the perceived significance of the barriers were highly statistically significant, χ2 (27) = 660.693, p < 0.001, validating that the order reflects genuine disparities in their perceived criticality.

Each of these top five barriers represents a fundamental challenge in urban renewal, particularly in high-density environments. Insufficient renewal funding is a key economic barrier, as limited financial resources hinder the initiation and sustainability of renewal projects. This is exacerbated by the rising costs of labor, materials, and the technical complexity of construction within confined spaces in high-density areas [53]. The high renewal costs factor further reinforces the financial challenge, as the costs associated with the renewal process often exceed the available budget, leading to compromises in project scope and quality [54].

On the social side, divergent resident demands and opinions and conflicts of interest among stakeholders create significant barriers. High-density communities tend to be socioeconomically diverse, with residents having varying expectations concerning relocation, compensation, and improvements in living conditions. Achieving consensus among such a diverse group is challenging, and this lack of consensus is often compounded by conflicts among external stakeholders, such as government agencies, developers, and designers, each with different priorities. The absence of mechanisms to mediate these competing interests frequently leads to decision paralysis and delays in project execution [1].

Lastly, complex property rights represent a foundational legal barrier that aggravates all other obstacles. In many old residential communities, unclear property ownership, informal structures, and mixed public–private property rights create legal uncertainties, making it difficult to secure investment and causing disputes over compensation and resettlement. This legal complexity not only prolongs negotiations but also intensifies social divisions and conflicts, further delaying the renewal process [1,55].

4.2.2. Factor Analysis of Barriers

Using principal axis factoring (PAF) with oblique rotation, a factor analysis was conducted on all questionnaire items. As shown in Table 7 the analysis extracted seven latent factors, collectively accounting for 56.76% of the total variance, which meets the threshold commonly recommended in social science research [56]. Each latent factor was then named according to the conceptual consistency of its high-loading items. Items with factor loadings below 0.4 were not simply discarded; instead, they were analyzed and interpreted after examining the composition of each latent factor. Although these items exhibit weaker statistical associations with the corresponding factors due to potential cross-loadings, some represent conceptually critical barriers in the context of the study. Retaining and discussing these items allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the factor structure while preserving theoretically important aspects of the barriers.

Table 7.

Factor analysis results (Pattern matrix loading).

While the scale demonstrated excellent overall reliability (CA = 0.915), a high CA value can sometimes signal potential item redundancy. To proactively rule this out and to rigorously evaluate the distinctiveness and internal coherence of the measured constructs, a latent factor-level reliability analysis was imperative. The results, detailed in Table 8, confirm that the high overall CA is a function of robust subscales rather than duplicated content. As shown, the CA for each latent factor ranged from 0.717 to 0.905, indicating acceptable to excellent reliability for all subscales. Critically, none of these values approached the excessive threshold (e.g., >0.95) that is a hallmark of redundancy. This conclusion is further strengthened by the examination of item-total correlation ranges within each latent factor (0.361 to 0.775). All values were positive and substantively meaningful, yet well below the extreme upper limit that would indicate items are synonymous. Collectively, this evidence robustly validates the factor structure, demonstrating that the scale reliably measures distinct latent factors without unnecessary duplication.

Table 8.

Reliability analysis results of latent factors.

The latent factors were interpreted as follows:

Latent factor 1: Policy and Planning Deficiencies—This includes lack of integrated and sustainable planning, lack of coordination mechanism in project approval, lack of standardized procedures, incomplete standards and regulations, lack of clear scientific and verifiable decision basis, slow project progress, lack of operable policy guidance, and unreasonable planning and design. This latent factor reflects systemic shortcomings in governance and decision-making structures. The lack of clear regulations, scientific evaluation criteria, and operable policy guidance not only slows project progress but also undermines the rationality and feasibility of urban renewal planning.

Latent factor 2: Infrastructure and Historical Legacy Issues—This includes difficult environmental remediation, severely aging infrastructure, historic and planning protection constraints. This latent factor reflects deep-rooted physical and institutional legacies that hinder urban renewal, such as deteriorated infrastructure, environmental contamination, and conflicts between preservation requirements and redevelopment needs.

Latent factor 3: Resident Participation and Community Consensus—This covers weak community identity among residents, low resident participation, and divergent resident demands and opinions. This latent factor addresses social challenges, including low community cohesion, limited public engagement, and divergent resident opinions. It emphasizes the importance of residents’ psychological identification and community consensus for project success.

Latent factor 4: Spatial and Physical Limitations—This involves issues such as space constraints for public facilities, limited transportation and construction space, and insufficient green and public spaces. This latent factor highlights physical constraints in urban renewal projects.

Latent factor 5: Execution and Management Inadequacies—This focuses on weak project management, ineffective information communication, technical constraints in construction, and multi-party coordination difficulty. This latent factor focuses on obstacles during the implementation stage, where inadequate managerial capacity, poor information flow, and technical or coordination challenges undermine execution efficiency. Even well-conceived plans can be delayed or compromised by weak implementation mechanisms.

Latent factor 6: Economic and Financial Constraints—This refers to low return on investment, insufficient renewal funding, and high renewal costs. This latent factor reflects economic and financial limitations, which directly constrain project initiation and sustainability.

Latent factor 7: Property Rights Complexity and Social Structure—These are characterized by comprising complex property rights, complex resident composition, inequitable compensation and resettlement allocation. At the core of this latent factor lies the challenge of property rights complexity, which undermines coordination, prolongs negotiation processes, and often provokes disputes. These legal and administrative difficulties are compounded by diverse social structures and unequal compensation arrangements, which magnify conflicts and hinder consensus in renewal projects.

While the factor loadings provided a clear structure of the relationships between the variables and their respective factors, some variables exhibited cross-loadings. The specific cross-loading values discussed here are derived from the pattern matrix of the EFA, as presented in Table 7. A barrier was considered to have a meaningful cross-loading if its loading on a secondary factor exceeded 0.2, as this indicates a substantive shared variance across constructs and is a commonly applied threshold for identifying such multidimensional relationships [56,57]. The occurrence of these cross-loadings highlights the multifaceted nature of certain barriers in urban renewal, suggesting that they cannot be simply categorized under a single latent factor but may interact across multiple dimensions. For instance, “Unreasonable planning and design” loaded 0.426 on the Policy and Planning Deficiencies factor and 0.233 on the Execution and Management Inadequacies factor, while “Divergent resident demands and opinions” loaded 0.463 on the Resident Participation and Community Consensus factor and −0.302 on the Property Rights Complexity and Social Structure factor. Similarly, “Multi-party coordination difficulty” showed loadings of 0.459 on Execution and Management Inadequacies and 0.210 on Policy and Planning Deficiencies. These cross-loadings highlight the interdependencies between barriers, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach to urban renewal that addresses both individual factors and their interactions. We will present these cross-loadings in Table 9 for clarity.

Table 9.

Barriers with Notable Cross-Loadings.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Ranked Barriers

Through the analysis of the results, we established a clear hierarchical structure of the 28 perceived barriers to urban renewal. Based on their mean scores, we identified the five most pressing barriers as follows: Insufficient Renewal Funding, Divergent Resident Demands and Opinions, Conflicts of Interest among Stakeholders, High Renewal Costs, and Complex Property Rights. These barriers represent the most critical challenges in the renewal of old residential communities, especially in high-density urban areas. We will discuss each of these barriers in detail, highlighting their interrelationships and how they collectively affect urban renewal processes.

- Ranked 1 st: Insufficient renewal funding

Insufficient renewal funding has long been the core barrier to urban renewal, especially in high-density areas. High-density regions typically have large-scale infrastructure and housing renewal demands, and public funding is limited, while financing options are not diverse enough. Thus, Insufficient renewal funding becomes a bottleneck for most urban renewal projects.

The high rank of Insufficient renewal funding reflects its critical role in the initiation, execution, and sustainability of renewal projects. In high-density environments, limited financial resources can lead to scaled-down projects or even project delays or cancellations. Moreover, funding problems are closely related to other barriers, such as property rights issues and Conflicts of interest among stakeholders. For example, developers are often hesitant to invest in properties with unclear ownership, which exacerbates financing difficulties.

- Ranked 2nd: Divergent resident demands and opinions

Divergent resident demands and opinions are another significant challenge in urban renewal, particularly in high-density areas where the diversity of residents’ needs and interests complicates consensus-building. Residents’ needs and expectations are often inconsistent, which increases decision-making complexity and directly impacts the social acceptability of renewal projects. The high ranking of this barrier demonstrates its significant impact on the social dimension of urban renewal. In many urban renewal projects, low participation, lack of trust, and opinion divergence are key causes of project delays. Low participation and trust often lead to resident opposition, which hinders decision-making and project implementation.

Additionally, divergent resident demands are closely tied to Insufficient renewal funding. If residents’ basic needs and expectations are not addressed, it may lead to resource waste or impact the project’s financing potential.

- Ranked 3rd: Conflicts of interest among stakeholders

Conflicts of interest among stakeholders are a common barrier in urban renewal projects, particularly when multiple stakeholders are involved. Conflicts between governments, developers, and residents often lead to delays and suboptimal decision-making.

The third-highest ranking of this barrier reflects the deep divisions between the government, developers, and residents, which are more pronounced in high-density areas. Governments aim to enhance the region’s value and functionality, while developers and residents may have conflicting interests. Residents often fear displacement, while developers seek to minimize costs and maximize returns. These conflicts usually manifest in land acquisition, compensation issues, and development planning, leading to project delays.

In this context, Insufficient renewal funding and divergent resident demands further amplify these conflicts. Without effective mediation and balance of interests, these conflicts severely affect the project’s progress.

- Ranked 4th: High Renewal Costs

High renewal costs are another critical factor that affects the feasibility of urban renewal projects. Especially in high-density areas, the costs of land and building demolition, repairs, and construction are extremely high, and due to land scarcity and high demand, construction costs are often beyond budget.

The high renewal costs are not limited to direct construction expenses but also include extra costs due to conflicts, delays, and compensation payments, making the project financially challenging. In many cases, economic feasibility becomes a key concern, as high costs can lead to lower return on investment, which may result in project delays or downsizing.

Moreover, high renewal costs are often related to Insufficient renewal funding. High costs put additional strain on financial resources, and in situations where economic conditions are unfavorable or public finances are strained, projects may struggle to secure sufficient funding.

- Ranked 5th: Complex Property Rights

Although complex property rights ranked fifth, they remain a fundamental barrier in the urban renewal process. Property complexity primarily refers to multiple ownerships, long-term leases, unclear ownership, and other issues, especially in high-density areas where the property rights structure is intricate and involves many stakeholders.

Complex property rights lead to significant legal barriers and ownership disputes during the land acquisition and demolition processes, which can cause legal conflicts and resident protests. In high-density urban renewal, the multifaceted property relationships make land acquisition and demolition more complex, often resulting in long and costly legal disputes.

Even though this issue ranked lower in the list, property rights problems have a profound and lasting impact on urban renewal projects. The long-term unresolved property disputes can lead to delays and even halting of the project. Addressing property rights issues is critical for the smooth implementation and long-term sustainability of urban renewal projects.

5.2. Discussion of Latent Factors Identified Through Factor Analysis

- Latent factor 1: Policy and Planning Deficiencies

Latent factor 1 highlights systemic shortcomings in top-level planning, policy guidance, and decision-making mechanisms specific to the RORCs in high-density urban areas. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating that urban renewal projects require strong institutional frameworks to coordinate complex initiatives [45,58], with such needs becoming particularly pronounced in densely built urban areas. Without coherent top-down planning, the renewal projects are vulnerable to delays, inconsistent decision-making, and misaligned stakeholder expectations [45,46]. Moreover, the lack of operable policy guidance often leads to ad hoc interventions, undermining long-term sustainability and efficiency [59]. These deficiencies not only delay project timelines but also increase uncertainty for all parties involved. For instance, unclear approval mechanisms can create bottlenecks at multiple administrative levels, leaving developers and contractors unable to anticipate the pace or sequence of required actions [10]. In high-density urban areas, where multiple stakeholders operate in close proximity, these gaps in planning and governance are magnified: limited land availability and overlapping jurisdictional responsibilities intensify conflicts and complicate decision-making. Moreover, inconsistencies in planning standards or incomplete regulations can result in projects that fail to meet broader urban sustainability objectives, such as efficient land use, environmental protection, and social inclusiveness [60]. Effectively addressing these challenges calls for the development of comprehensive urban renewal guidelines that integrate multi-level governance, codify procedures, and embed sustainability goals—thereby helping transform institutional structures from impediments into active facilitators of RORCs advancement.

These Policy and Planning Deficiencies are closely linked to economic and financial constraints (latent factor 6) and execution and management inadequacies (latent factor 5). Inadequate planning and a lack of standardized procedures exacerbate financial challenges by hindering efficient resource allocation and increasing funding uncertainty. Poor governance and unclear policy guidance also contribute to project delays, amplifying management inefficiencies and complicating stakeholder coordination. Additionally, property rights complexity (latent factor 7) adds further complexity to planning, as unclear ownership structures delay permits and approvals, worsening planning inefficiencies. Resident participation and community consensus (latent factor 3) are also impacted by institutional weaknesses, preventing effective engagement and complicating decision-making. In summary, Policy and Planning Deficiencies not only hinder project effectiveness but also create a cascading impact across other factors, highlighting the need for a holistic approach to urban renewal that addresses governance, finance, execution, and community involvement.

- Latent factor 2: Infrastructure and Historical Legacy Issues

In the RORCs within dense urban areas, aging infrastructure, environmental remediation challenges, and historic preservation constraints constitute a legacy barrier with significant implications for project feasibility and cost. Dense urban neighborhoods often contain deteriorated utilities, poorly maintained public spaces, and protected historic buildings, which constrain renewal options and increase technical complexity [20,61]. These conditions require careful assessment, phased remediation, and adaptive design strategies to balance modernization with heritage preservation [62]. In RORCs, such legacy problems are often deeply embedded in the built environment, where outdated water, sewage, and power systems coexist with residential buildings still in use [20]. The coexistence of long-term residents, limited construction access, and overlapping infrastructure networks further complicates renewal activities [6]. Moreover, historical preservation requirements frequently restrict demolition or large-scale reconstruction, forcing project teams to adopt incremental upgrading rather than wholesale renewal [39]. These intertwined challenges increase both cost and uncertainty, while extending project timelines. Consequently, the technical feasibility of RORCs depends on integrated planning approaches that coordinate infrastructure rehabilitation, environmental treatment, and heritage protection within the same spatial and social framework. This highlights the need for cross-disciplinary collaboration among engineers, planners, and conservation specialists to achieve sustainable renewal outcomes in dense urban contexts.

The Infrastructure and Historical Legacy Issues are closely linked with Policy and Planning Deficiencies (Latent Factor 1) and Economic and Financial Constraints (Latent Factor 6). A lack of coordinated top-down planning and standardized procedures for managing aging infrastructure exacerbates the difficulties faced in upgrading deteriorating systems and preserving historical sites [45]. Without a clear and structured planning framework, the process of integrating environmental remediation and heritage conservation becomes ad hoc, increasing the complexity of the overall renewal strategy. Additionally, the significant costs involved in environmental remediation and infrastructure upgrades contribute to the economic burden of the renewal projects, particularly in densely populated urban areas where land values and construction costs are already high. This economic strain is further compounded by the need for specialized financial mechanisms to support both infrastructure revitalization and historical preservation, often resulting in budget overruns and project delays. Furthermore, the preservation of historic buildings complicates the property rights negotiations. Legal restrictions on demolition or renovation, combined with owner resistance to redevelopment, can prolong negotiations and significantly alter the scope and timeline of renewal projects [39]. Thus, addressing the physical, economic, and regulatory challenges of infrastructure renewal requires coordinated planning and cross-disciplinary collaboration that integrates technical, financial, and legal expertise.

- Latent factor 3: Resident Participation and Community Consensus

The third latent factor highlights socially related barriers specific to RORCs in dense urban areas, including weak community identity, low resident participation, and divergent demands. Dense urban communities often comprise diverse populations with varying socioeconomic backgrounds, expectations, and historical experiences, making consensus difficult to achieve [63]. Low participation and weak social cohesion can generate resistance, reduce compliance with renovation plans, and amplify conflicts during implementation [27]. Effective participation in RORCs requires not only information dissemination but also mechanisms for genuine engagement, such as resident advisory boards, workshops, and collaborative design sessions tailored to local needs [2]. These mechanisms enhance trust, facilitate conflict resolution, and improve the social legitimacy of renewal projects. In practice, managing divergent expectations in dense urban RORCs often involves mediating between short-term individual interests and long-term collective benefits, a challenge intensified by population density and fragmented property rights [64]. Beyond the previously discussed effects, barriers in this latent factor with planning, execution, and property rights barriers, with weak engagement amplifying the social consequences of flawed planning, project delays, and unclear ownership, underscoring the need for integrated strategies that address social, technical, and institutional dimensions.

This latent factor interacts with Policy and Planning Deficiencies (Latent Factor 1), Execution and Management Inadequacies (Latent Factor 5), and Property Rights Complexity (Latent Factor 7). Weak community engagement exacerbates the social consequences of poor planning, project delays, and unclear ownership issues, particularly in dense urban areas. Insufficient participation can amplify the negative impacts of poorly coordinated planning and inadequate project management [58]. Moreover, the fragmented nature of property rights in high-density urban areas complicates consensus-building, as residents’ interests often conflict with developers’ or governmental priorities. Without effective communication channels and participatory mechanisms, these issues remain unresolved, perpetuating delays and resistance.

- Latent factor 4: Spatial and Physical Limitations

Spatial and physical constraints emerged as a distinct barrier, including limited space for public facilities, restricted transportation and construction areas, and insufficient green and public spaces. High-density urban neighborhoods present unique physical constraints: dense building coverage, narrow streets, and existing structures limit both the scale and approach of RORCs [39]. These limitations affect not only construction logistics but also the quality of life outcomes for residents, such as accessibility to public amenities and green spaces. Theoretically, this aligns with urban morphology and spatial planning frameworks emphasizing the optimization of limited space through innovative design, vertical expansion, or phased redevelopment. Practically, strategies such as modular construction, adaptive reuse, and incremental development allow for efficient land use while maintaining service quality.

These spatial and physical constraints also interact with other key barriers, particularly economic and financial constraints (Latent Factor 6) and execution and management inadequacies (Latent Factor 5). The limited space for construction increases costs and complicates execution logistics, as construction methods must be adapted to fit the confined spaces of high-density urban areas. These physical constraints also restrict resident participation, as the available spaces for public engagement are limited [65]. The physical limitations also exacerbate economic challenges, as space constraints can result in higher construction costs and may lead to compromises in design quality. Overcoming these barriers requires innovative design strategies and adaptive reuse solutions, as well as better integration of construction management and community engagement.

- Latent factor 5: Execution and Management Inadequacies

Execution-related barriers emerged as a distinct component, including weak project management, ineffective information communication, technical constraints in construction, and multi-party coordination difficulties. In the context of high-density urban areas, even a strategically sound plan for the RORCs can be impeded by these factors, obstructing its translation into on-the-ground progress. Existing studies indicate that misalignment among administrative departments, insufficient managerial capacity, and a lack of specialized technical expertise are critical sources of delays and cost overruns in dense urban renewal projects [43,58]. Ineffective communication can lead to misunderstandings among stakeholders, misallocation of resources, and resistance from local communities [21]. Technical constraints, including the inability to adapt construction methods, limit both efficiency and safety [17], and these challenges are particularly severe in the confined spaces of high-density urban areas. Based on expert interviews conducted in this study, experts highlighted that in high-density urban environments for the RORCs, space constraints require adaptation of standard construction methods, but limited technical capacity and inadequate site planning often hinder this process. Multi-party coordination is also complicated by overlapping responsibilities among government agencies, contractors, and community groups, leading to delays and disputes. The combined effects of weak management, poor communication, and technical constraints can increase costs, reduce quality, and provoke local resistance. To address these challenges, experts recommended strengthening project teams’ technical and managerial skills, improving communication and coordination channels, and deploying construction technologies suited to high-density urban contexts.

Moreover, these latent factors are closely tied to Policy and Planning Deficiencies (Latent Factor 1), Economic and Financial Constraints (Latent Factor 6), and Resident Participation and Community Consensus (Latent Factor 3). Weak project management and poor communication exacerbate the social challenges of low resident participation, as misunderstandings and resistance from communities can result in further delays and inefficiencies. Moreover, lack of coordination between various departments and stakeholders leads to budget overruns and project delays. Effective exeution depends on strengthening both technical expertise and managerial capacity, alongside better communication and coordination among stakeholders.

- Latent factor 6: Economic and Financial Constraints

Economic and financial constraints, including low return on investment, insufficient renewal funding, and high renovation costs, were identified as a separate critical category of barriers to RORCs in high-density urban areas. Financial feasibility is often the decisive criterion in dense urban communities, where land values, construction costs, and labor expenses are high [66]. Limited funding can hinder the adoption of advanced construction techniques, reduce quality standards, and constrain stakeholder engagement, thereby exacerbating execution and social barriers [58]. To overcome these financial constraints, another study underscores the importance of diversified financing mechanisms—such as public–private partnerships, government subsidies, and value capture strategies—to enhance project feasibility and promote broader participation [67]. In line with this perspective, Chinese cities have adopted innovative approaches by leveraging land-use rights and development incentives to support urban renewal while ensuring social equity [68].

Moreover, these economic barriers intensely interact with spatial, technical, and infrastructural constraints. Specifically, they exacerbate Spatial and Physical Limitations (Latent Factor 4), as high costs stemming from spatial constraints can restrict the scope of physical interventions, force compromises in design quality [69], and hinder large-scale renewals. Concurrently, they compound Infrastructure and Historical Legacy Issues (Latent Factor 2), where limited funding can delay critical environmental remediation and infrastructure upgrades. These combined financial and physical challenges further restrict the scope of renewal projects and complicate effective stakeholder engagement. Therefore, to ensure sustainable and socially inclusive outcomes, effective financial planning must strategically balance economic viability with technical feasibility and social acceptability.

- Latent factor 7: Property Rights Complexity and Social Structure

The final Latent factor underscores a set of intertwined legal and social barriers in high-density RORCs. Complex ownership structures, diverse resident composition, and inequitable compensation arrangements create obstacles to coordination, decision-making, and conflict resolution [55] Property rights complexity is particularly critical in dense urban neighborhoods, where overlapping claims and unclear titles can delay projects or trigger disputes [14]. Resident diversity and compensation disagreements exacerbate social tensions [14], but the unresolved property rights issue remains the fundamental barrier. Addressing this challenge requires legal clarity, fair compensation mechanisms, and structured negotiation processes that integrate residents’ input. International experiences suggest that clearly defined ownership rights significantly improve renewal success rates and reduce social conflict [19,28,44]. Practically, local governments must implement property registration reforms, standardized compensation frameworks, and participatory negotiation platforms to resolve ownership disputes and facilitate coordinated urban renewal.

This latent factor intersects with almost all other latent factors, particularly with Policy and Planning Deficiencies (Latent Factor 1) and Resident Participation (Latent Factor 3). Legal and administrative barriers related to property rights complicate coordinated planning and community engagement, while unequal compensation arrangements can generate social tensions, prolonging negotiations and delaying project timelines. Resolving property rights issues requires legal clarity, fair compensation mechanisms, and participatory negotiation platforms, which are essential for reducing social conflict and ensuring a smoother renewal process.

The seven latent factors collectively reveal the multi-dimensional and interdependent nature of the barriers to RORCs in high-density urban areas. Institutional deficiencies amplify execution difficulties; economic constraints interact with spatial and technical limitations; social barriers are closely linked to property rights complexity. These findings underscore the necessity for integrated strategies that address governance, finance, technical innovation, spatial design, social engagement, and legal frameworks simultaneously. For policymakers and practitioners, the results highlight that piecemeal approaches are insufficient: successful RORCs in high-density urban areas require coordinated, systemic interventions that consider the interrelations among structural, economic, spatial, social, and legal factors.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive examination of the barriers impeding the RORCs in high-density urban areas. By integrating a literature review, expert consultation, and survey-based empirical analysis, twenty-eight specific barriers were identified and distilled into seven interconnected latent factors through EFA: (1) Policy and Planning Deficiencies, (2) Execution and Management Inadequacies, (3) Economic and Financial Constraints, (4) Spatial and Physical Limitations, (5) Resident Participation and Community Consensus, (6) Infrastructure and Historical Legacy Issues, and (7) Property Rights Complexity and Social Structure. Collectively, these latent factors reveal that the renewal of dense urban communities is shaped not by discrete technical or financial issues alone, but by a deeply interwoven system of institutional, economic, spatial, social, and legal factors that jointly determine renewal feasibility and sustainability.

The findings demonstrate that institutional and governance deficiencies often serve as the root of systemic inefficiency, amplifying challenges in implementation, financing, and coordination among diverse stakeholders. Economic and financial pressures—particularly high renovation costs and Insufficient renewal funding—further constrain the scope and quality of renewal projects. Meanwhile, spatial limitations, aging infrastructure, and heritage conservation demands impose additional physical and technical constraints, while low resident participation and weak community identity undermine social cohesion and legitimacy. Among all, the complexity of property rights remains the most fundamental obstacle, embedding uncertainty, inequity, and conflict into the very foundation of the renewal process. These interdependencies underscore that successful renewal in high-density contexts demands integrated, cross-sectoral approaches rather than isolated policy or technical solutions.

The theoretical contribution of this research lies in the development of a systemic analytical framework for understanding barriers to high-density urban renewal. Moving beyond the typical approach in existing literature, which treats barriers in isolation, our framework explicitly analyzes the interdependent and cascading nature of these challenges. It shows that barriers are not merely independent issues, but form a complex system in which deficiencies in one domain amplify challenges in others. For example, our factor analysis revealed that Property Rights Complexity is not just a legal issue, but also fundamentally constrains planning, fuels social conflict, and deters investment. Similarly, Economic Constraints are exacerbated by Spatial Limitations and Infrastructure Legacy Issues.

Based on our findings, this study presents several targeted and actionable recommendations for overcoming the barriers to RORCs in high-density urban areas:

- (1)

- Immediate Priority: Establish Integrated Financing and Governance Mechanisms. In high-density urban areas where land value is high but redevelopment space is limited, financial constraints are critical. To address this, we recommend creating district-scale renewal funds that consolidate smaller projects into larger, more financially viable districts. This attracts private investment and spreads risk. Implement value-capture mechanisms to allow local governments to recapture a portion of land value uplift, funding further urban renewal projects. Linking funding to pre-approved planning standards for typical renewal typologies ensures efficiency and reduces financial risks while adapting to the specific challenges of space-constrained urban areas.

- (2)

- Core Focus: Deploy Differentiated Participatory Models to Build Consensus. In densely populated urban areas, social barriers such as divergent resident demands and conflicts among stakeholders must be addressed. Use digital platforms for large-scale outreach to facilitate broad engagement across high-density communities. Establish resident working groups to ensure that local needs are considered in detailed planning. For complex issues like relocation and compensation, implement deliberative forums with binding outcomes, ensuring fair participation. Transparent benefit-sharing frameworks should be developed early, addressing specific urban renewal challenges to reduce conflicts and foster trust between residents, developers, and policymakers.

- (3)

- Foundational Reform: Systematize Property Rights Clarification and Innovative Legal Models. In high-density urban renewal, property rights complexity exacerbates legal uncertainty. To facilitate renewal, pre-renewal title audits should resolve ambiguities in property ownership, ensuring legal readiness for redevelopment. Introduce regularization programs to formalize informal property arrangements, boosting investment confidence. Explore innovative legal models, like shared-equity or usufruct schemes, to separate development rights from usage rights, ensuring that renewal projects progress while safeguarding resident interests and providing equitable solutions in land-scarce urban environments.

Future research could extend these insights by adopting comparative, longitudinal, or modeling approaches to capture how these barriers interact dynamically across time and institutional contexts. Linking such empirical evidence with theories of collaborative governance and complex adaptive systems would further enrich our understanding of how renewal processes can evolve toward greater inclusiveness, resilience, and sustainability. Ultimately, the renewal of old residential communities in high-density cities is not only a technical or economic challenge, but a test of institutional adaptability and social trust—one that will shape the trajectory of sustainable urban transformation in the decades to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and S.M.; methodology, S.Z. and L.L.; validation, L.L.; formal analysis, X.F.; investigation, L.L. and X.F.; resources, G.C.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.Z. and L.L. and G.C. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province], grant number [ZR2024QG245], and [2025 Shanghai High Level Institution Construction and Operation Plan “Soft Science Research” Project], grant number [25692111900].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as the research involves anonymous surveys with adult participants, where no personally identifiable information is collected and the study involves no more than minimal risk by Qingdao University of Technology.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the financial support of the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RORCs | Renewal of Old Residential Communities |

References

- Liang, Y.; Qian, Q.K.; Li, B.; An, Y.; Shi, L. A Critical Assessment on China’ s Old Neighborhood Renovation: Barriers Analysis, Solutions and Future Research Prospects. Energy Build. 2025, 332, 115407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W. Collaborative Workshop and Community Participation: A New Approach to Urban Regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Jia, L. Decision-Making Factors for Renovation of Old Residential Areas in Chinese Cities under the Concept of Sustainable Development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 39695–39707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, M.; Pérez, R.; Laprise, M.; Rey, E. Fostering Sustainable Urban Renewal at the Neighborhood Scale with a Spatial Decision Support System. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Yang, X. Impact of Social Capital on Residents’ Willingness to Participate in Old Community Renewal in China: Mediating Effect of Perceived Value. Cities 2025, 159, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. Factors Affecting Urban Renewal in High-Density City: Case Study of Hong Kong. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2008, 134, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Jiménez, A.; Lima, M.L.; Molina-Huelva, M.; Barrios-Padura, Á. Promoting Urban Regeneration and Aging in Place: APRAM—An Interdisciplinary Method to Support Decision-Making in Building Renovation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zajch, A.M.; Shimoda, Y.; Yang, W. Evaluating New Construction-Led vs. Renovation-Led Building Energy Codes for Life Cycle Carbon Reduction Potential under Urban Development Transition. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A New Style of Urbanization in China: Transformation of Urban Rural Communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Hu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, T.; Yu, F. Resident-Led Renewal Models in Historic Cities: Historical Review, Institutional Barriers, and Policy Framework. Urban Plan. Forum 2025, 38, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, Q.; Liu, G.; Wu, Y.; Li, K.; Hong, J. Determining Critical Success Factors of Urban Renewal Projects: Multiple Integrated Approach. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2022, 148, 04021058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Xia, N.; Ni, W. Critical Success Factors for the Management of Public Participation in Urban Renewal Projects: Perspectives from Governments and the Public in China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2018, 144, 04018026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Bao, H.; Yau, Y.; Skitmore, M. Case-Based Analysis of Drivers and Challenges for Implementing Government-Led Urban Village Redevelopment Projects in China: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 05020014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cete, M.; Konbul, Y. Property Rights in Urban Regeneration Projects in Turkey. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, N. Regeneration for Sustainable Communities? Barriers to Implementing Sustainable Housing in Urban Areas. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 330, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Koo, J.H. What Is the Critical Factor and Relationship of Urban Regeneration in a Historic District?: A Case of the Nanluoguxiang Area in Beijing, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegay, F.G.; Mwanaumo, E.; Mwiya, B. Construction Site Layout Planning Practices in Inner-City Building Projects: Space Requirement Variables, Classification and Relationship. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2023, 11, 2190793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. The Place-Shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, T. A Research Review on the Transformation of Old Districts A Research Review on the Transformation of Old Districts. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 052104. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Yuan, S. Research on Assessment Methods and Practical Analysis of Livable Communities in Chongqing from an Urban Renewal Perspective. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Cao, H. Co-Creating for Locality and Sustainability: Design-Driven Community Regeneration Strategy in Shanghai’s Old Residential Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, S.C.; Rabinovich, A.; Barreto, M. Putting Identity into the Community: Exploring the Social Dynamics of Urban Regeneration. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 789–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G. Key Variables for Decision-Making on Urban Renewal in China: A Case Study of Chongqing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, M.; Guan, N.; Zhang, L.; Gu, T. Research on the Influencing Factors of Residents’ Participation in Old Community Renewal: A Case Study of Nanjing. Constr. Econ. 2019, 40, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y. Exploring the Key Factors Influencing Sustainable Urban Renewal from the Perspective of Multiple Stakeholders. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liang, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Wang, G. An Optimization Model for Managing Stakeholder Conflicts in Urban Redevelopment Projects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.Q. Planning and Politics: Citizen Participation in Urban Renewal. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 2007, 29, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Lai, Y.; Tao, L.; Lin, Y. Spatial Variation of Industrial Land Conversion and Its Influential Factors in Urban Redevelopment in China: Case Study of Shenzhen, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, K.; Liu, K.; Ma, J.; Li, W. Study on the Application of BIM Technology and Optimisation of Construction Management in Urban Renewal Projects. J. Glob. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2025, 6, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shrestha, A.; Martek, I.; Wei, L. An Evaluation of Urban Renewal Policies of Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Cheng, Q. An Evaluation of Urban Renewal Based on Inclusive Development Theory: The Case of Wuhan, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, W.; Xing, Z. Current Situation and Sustainable Renewal Strategies of Public Space in Chinese Old Communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Shen, G.Q.; Liu, G.; Martek, I. Demolition of Existing Buildings in Urban Renewal Projects: A Decision Support System in the China Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Kikidou, M.; Patelida, M.; Somarakis, G. Engaging Citizens in Planning Open Public Space Regeneration: Pedio Agora Framework. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2018, 144, 05017016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Goswami, S.S. Evaluating Critical Factors for Urban Renewal along the Jinghang Grand Canal: An Integrated MCDM Approach for Heritage Preservation and Urban Development. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhang, L.; Cui, P.; Yuan, J. Exploring the Evolution Mechanisms of Social Risks Associated with Urban Renewal from the Perspective of Stakeholders. Buildings 2024, 14, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Kivrak, S.; Arslan, G. Contribution of Built Environment Design Elements to the Sustainability of Urban Renewal Projects: Model Proposal. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 145, 04018045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, X. Spatial Evolution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Historic Urban Areas: A Case Study of Zhangye Historic Centre, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, J. Sustainable Renewal of Historical Urban Areas: A Demand–Potential-Constraint Model for Identifying the Renewal Type of Residential Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F. Unraveling the Renewal Priority of Urban Heritage Communities via Macro-Micro Dimensional Assessment-A Case Study of Nanjing City, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 124, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinsziehr, T.; Grossmann, K.; Gröger, M.; Bruckner, T. Building Retrofit in Shrinking and Ageing Cities: A Case-Based Investigation. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 45, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhang, H.; Feng, J. Factors Driving Social Capital Participation in Urban Green Development: A Case Study on Green Renovation of Old Residential Communities Under Urban Renewal in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Hall, R.P.; Yoon, T. The Complex Relationship between Capacity and Infrastructure Project Delivery: The Case of the Indian National Urban Renewal Mission. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Yau, Y.; Bao, H.; Liu, Y. Anatomizing the Institutional Arrangements of Urban Village Redevelopment: Case Studies in Guangzhou, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Qiu, B.; Wu, Y. Exploration of Urban Community Renewal Governance for Adaptive Improvement. Habitat Int. 2024, 144, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. The Network Governance of Urban Renewal: A Comparative Analysis of Two Cities in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Curran, P.G.; Keeney, J.; Poposki, E.M.; Deshon, R.P.; Journal, S.; March, N.; Huang, J.L.; Curran, P.G.; Keeney, J.; et al. Detecting and Deterring Insufficient Effort Responding to Surveys. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 27, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, J.A.; Harms, P.D.; Desimone, A.J. Best Practice Recommendations for Data Screening. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Shen, Q.; Pan, W.; Ye, K. Major Barriers to Off-Site Construction: The Developer’s Perspective in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barendse, M.T.; Oort, F.J.; Timmerman, M.E.; Barendse, M.T.; Oort, F.J.; Timmerman, M.E. Using Exploratory Factor Analysis to Determine the Dimensionality of Discrete Responses Using Exploratory Factor Analysis to Determine the Dimensionality of Discrete Responses. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2015, 22, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Yuan, M. Critical Factors Influencing Interface Management of Prefabricated Building Projects: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.T.; Zhao, Z.B. Exploration of Customer Satisfaction Measurement: Scale Design, Reliability, and Validity. Chinese J. Manag. 2008, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, T.; Han, M.; Edwin, C.H. Synergies and Trade-Offs in Achieving Sustainable Targets of Urban Renewal: A Decision-Making Support Framework. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 52, 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Dai, X.; He, C.; Liu, B. Beyond Land Finance: Exploring the Fiscal Revenue Effects of Urban Renewal in Guangdong Province, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 05025041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Chan, E.H.W.; Yung, E.H.K. Alternative Governance Model for Historical Building Conservation in China: From Property Rights Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Recommendations for Getting the Most from Your Analysis Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; Maccallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. An Analysis of Urban Renewal Decision-Making in China from the Perspective of Transaction Costs Theory: The Case of Chongqing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 1177–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmany, H.; Hananel, R. The Fourth Generation: Urban Renewal Policies in the Service of Private Developers. Habitat Int. 2022, 125, 102580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Liu, G.; Lang, W.; Shrestha, A.; Martek, I. Strategic Approaches to Sustainable Urban Renewal in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Md Ali, Z.; Nik Hashim, N.H.; Ahmad, Y.; Wang, H. Evaluating Social Sustainability of Urban Regeneration in Historic Urban Areas in China: The Case of Xi’an. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Langston, C.; Chan, E.H.W. Adaptive Reuse of Traditional Chinese Shophouses in Government-Led Urban Renewal Projects in Hong Kong. Cities 2014, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Approach for Assessment of Urban Renewal Proposals. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. Stakeholders’ Expectations in Urban Renewal Projects in China: A Key Step towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, S.; Götze, V.; Hauck, L.; Stalder, N. The Amplifying Effect of Spatial Planning Restrictions on House Prices and Rents. J. Hous. Econ. 2025, 69, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Fu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, P.; Wu, C. Analysis of Urban Commercial and Business Land Value under Planning-Oriented Approach: A Case Study of the Central Urban Area of Wuhan. J. Urban Rural Plan. 2024, 13, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, C.; de Jong, M. Financing Eco Cities and Low Carbon Cities: The Case of Shenzhen International Low Carbon City. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.S. The Redevelopment of China’s Construction Land: Practising Land Property Rights in Cities through Renewals. China Q. 2015, 224, 865–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.; Gyourko, J. The Economic Implications of Housing Supply. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |