Navigating Sustainability: The Green Transition of the Port of Bar

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Which combination of technological, operational and management measures provides the greatest feasibility and impact for the decarbonization of a small Adriatic port under existing constraints?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Empirical Evidence on Port Sustainability

2.3. Port Performance and Innovation

2.4. Identified Research Gaps

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Empirical Modeling

3.2. Theoretical Modeling and Scenario Design

- The basic scenario, which reflects the current operating conditions;

- The medium scenario, which includes partial electrification and integration of renewable energy sources;

- An advanced scenario targeting the complete decarbonization and digitization of port operations.

3.3. Expert Consultation and Qualitative Validation

3.4. Integration of Findings and Methodological Framework

4. Results

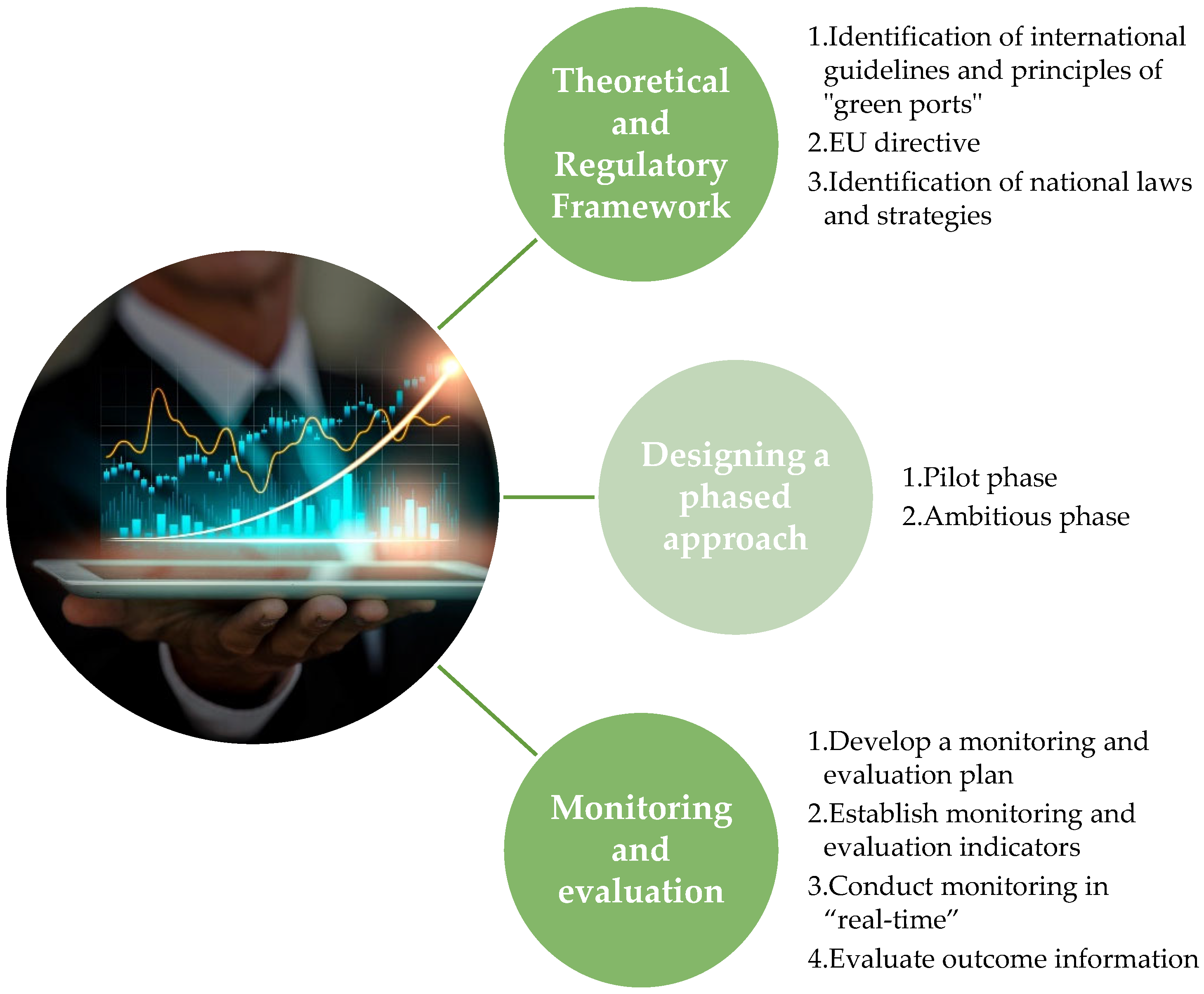

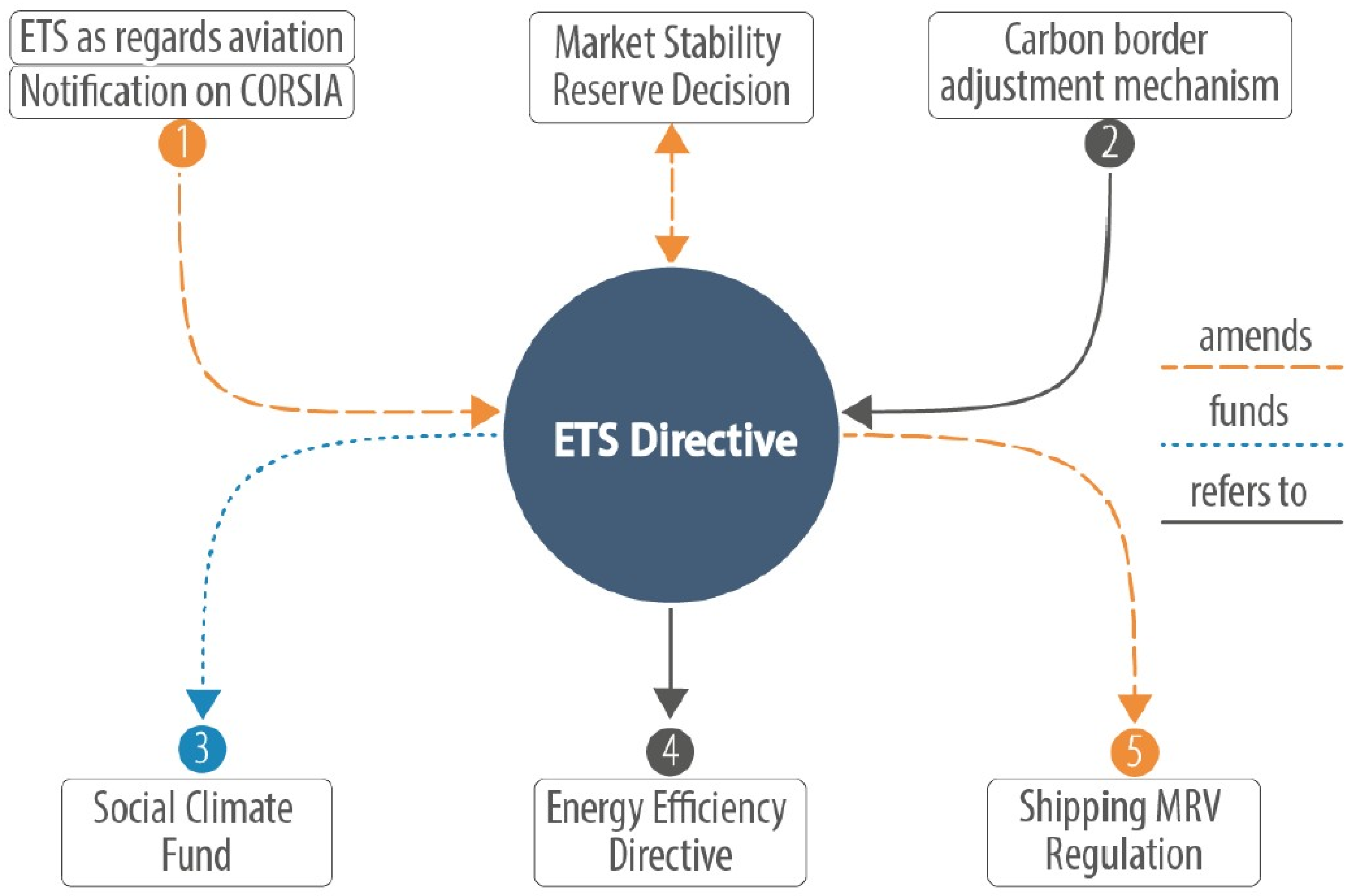

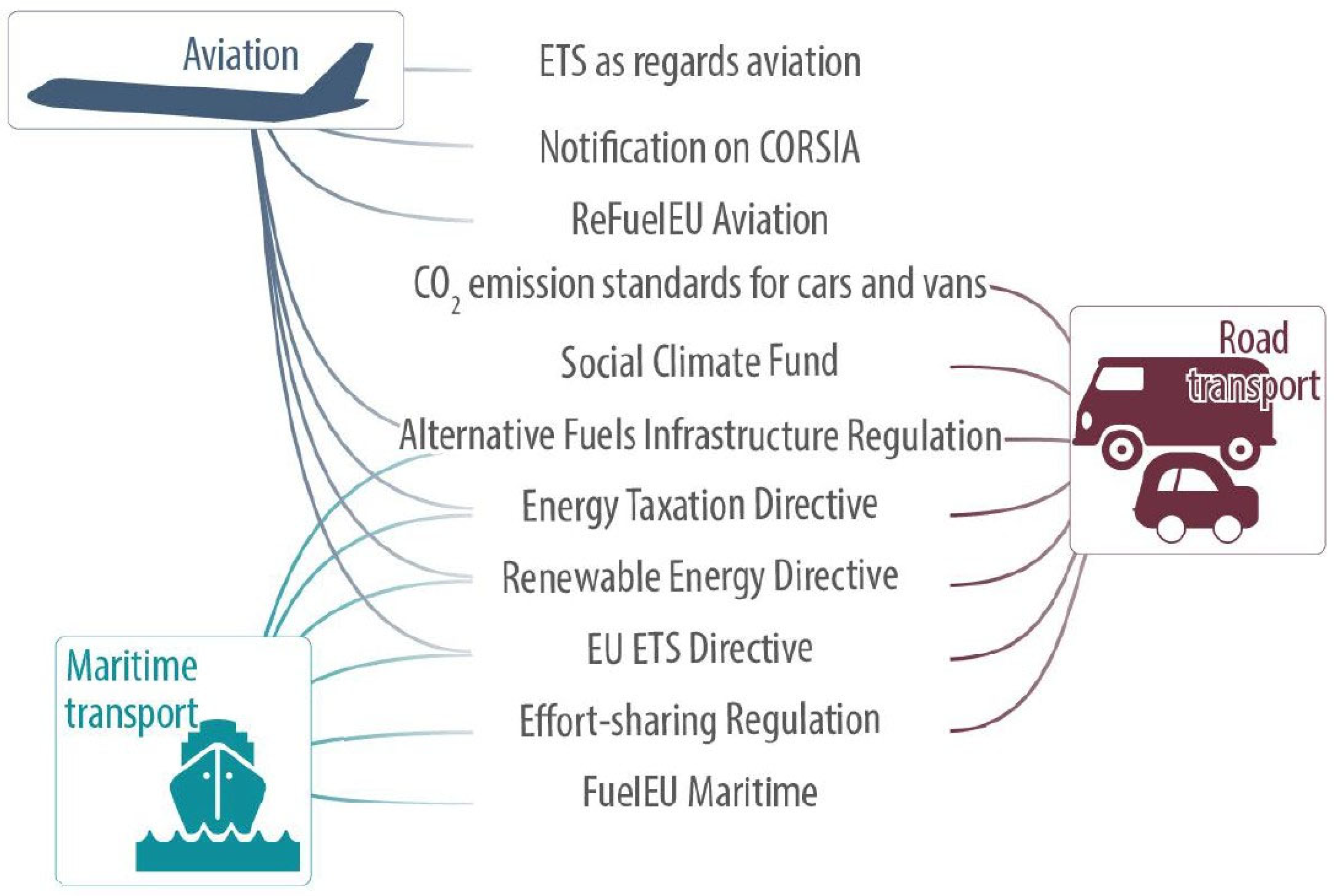

4.1. Theoretical and Regulatory Framework

4.1.1. International Regulations and Conventions

- The Paris Agreement

- European Green Deal

- Emissions reduction targets across a broad range of sectors;

- A target to boost natural carbon sinks;

- An updated emissions trading system to cap emissions, put a price on pollution and generate investments in the green transition;

- Social support for citizens and small businesses.

- Fit for 55 Package

4.1.2. Identification of National Laws and Strategies

- The Law on Energy Efficiency

- The Strategy for the Development of Montenegro’s Energy Sector by 2030

- The National Strategy for Sustainable Development by 2030

- Increase the share of renewable sources of energy and promote rational use of them, with the following stated as the target outcome for 2030:

- -

- The level of GHG emissions by 2030 is reduced by 30% in comparison to 1990 level;

- -

- Achieved national target of renewable energy sources share in gross final energy consumption of 33% in 2020 and set a more ambitious goal for 2030;

- -

- Achieved indicative target of energy efficiency (9% by 2018) and set a more ambitious goal for 2030;

- -

- Increased fiscal and regulatory incentives for renewable energy promotions and energy efficiency.

- Establish an eco-fund and promote the mobilization of financial resources for sustainable development, including new economical instruments (such as green fiscal reform), with the following stated as the target outcome for 2030:

- -

- Established eco-fund;

- -

- Responsible public consumption, in accordance with the principles of sustainable development;

- -

- Predictable public finance and credible mid-term planning, along with measurement of the effects of consumption, improvement of the country’s credit rating, and support for the development of the green economy.

- Provide financial support for the development of mechanisms and capacities to introduce green economy within ten priority sectors, where among others, the following sub-measures are listed:

- -

- Development of sustainable renewable energy sources and reduction of emissions and environmental pressures;

- -

- Energy efficiency;

- -

- Sustainable production and consumption for efficient use of resources and strengthening the competitiveness (manufacturing industry, services, small and medium-sized enterprises).

- Secured domestic and international private sources of financing for sustainable development and the creation of green jobs;

- Improved policy coherence for sustainable development, including enhanced coordination.

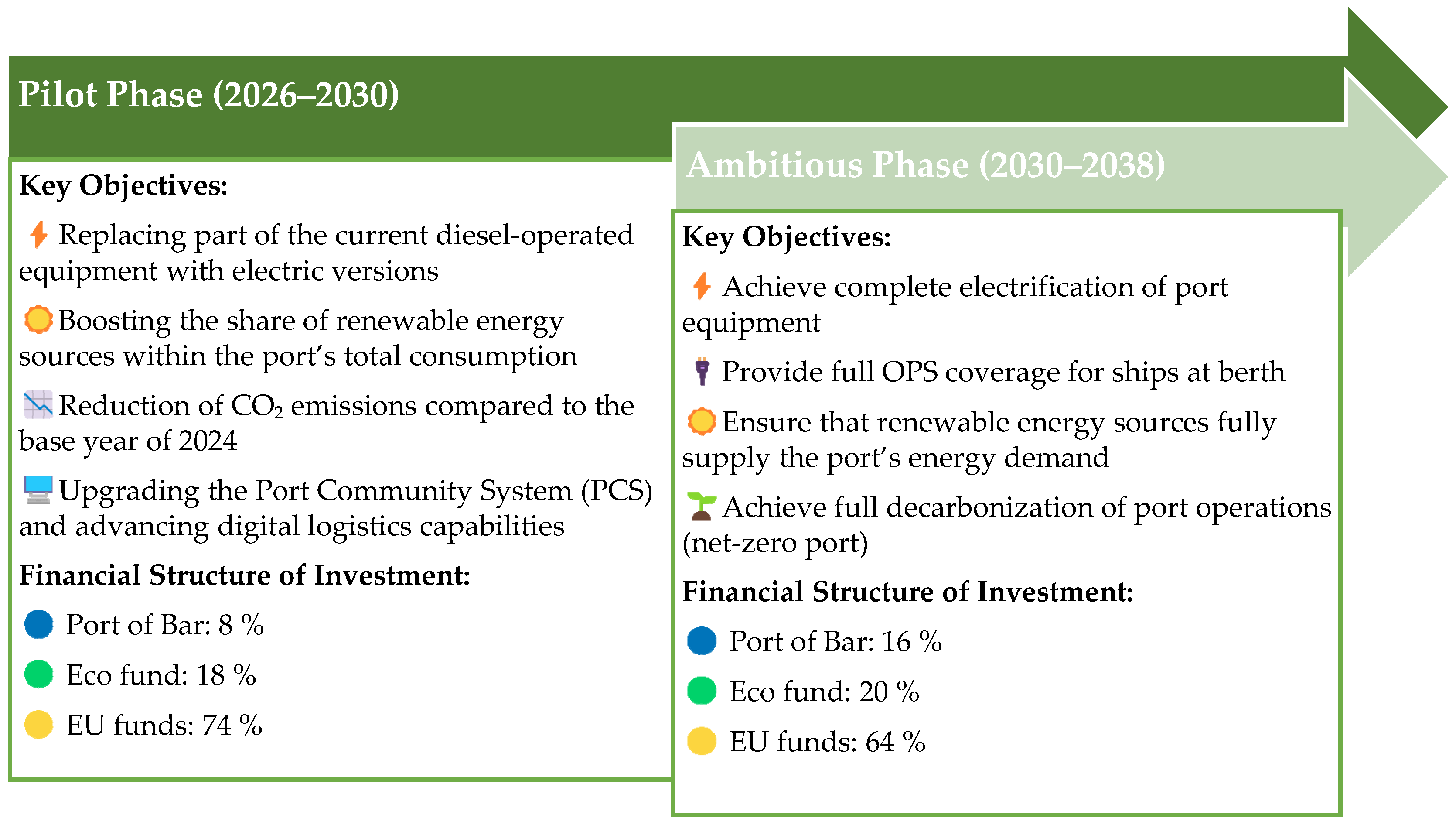

4.2. A Phased Approach

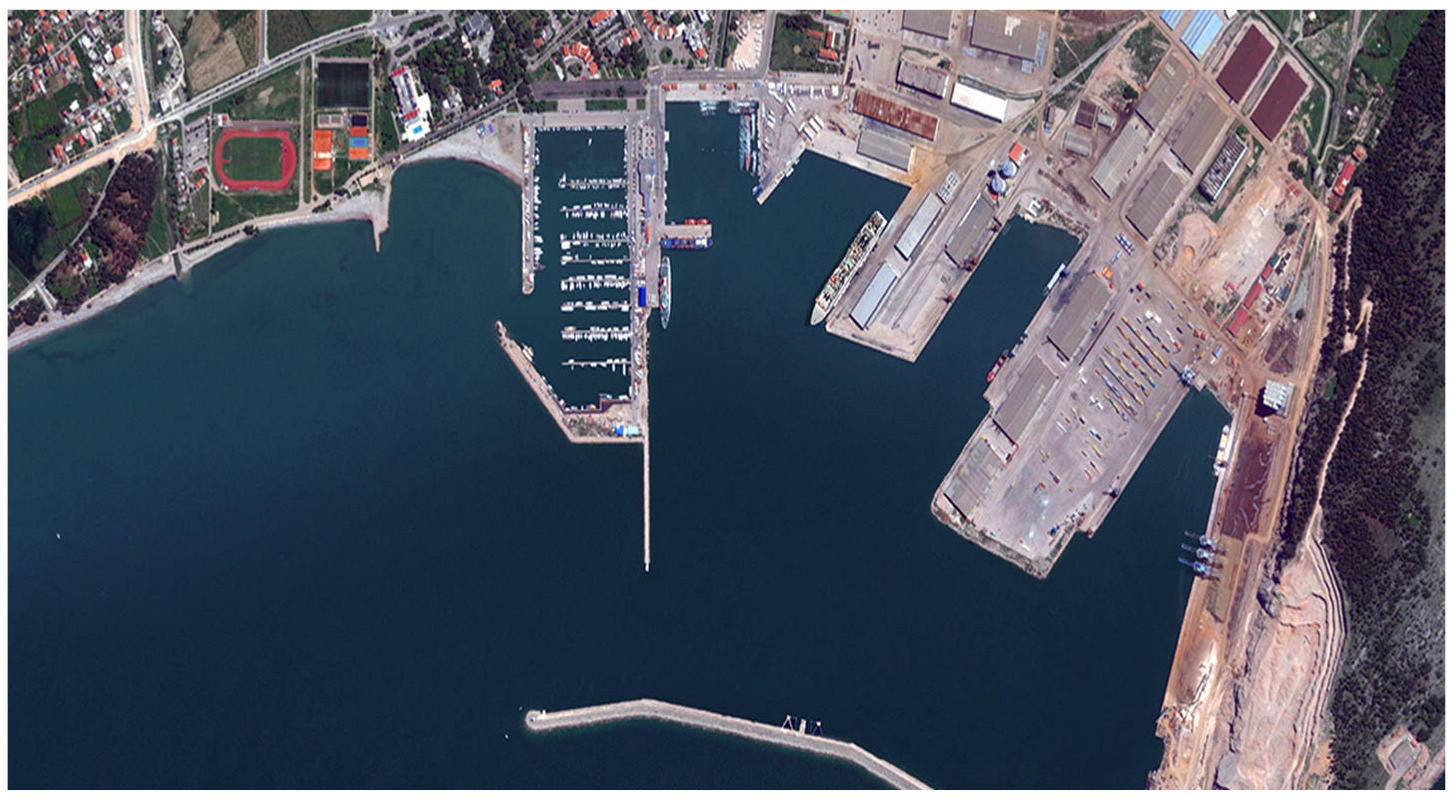

- Enclosed port warehouses: No. 10 (area 6300 m2) and No. 13 (area 5982 m2);

- Grain silo with storage capacity of 30,000 tons;

- Cold storage—7749 m2;

- Prefabricated warehouse—1200 m2;

- Prefabricated warehouse—600 m2;

- Modular/demountable warehouse (inflatable hall)—4590.4 m2;

- Warehouses: B1—48 m2, M2—216 m2, M3—216 m2, M4—1159 m2.

4.2.1. First Pilot Phase 2026–2030

Key Objectives

- Boosting the share of renewable energy sources within the port’s total consumption;

- Replacing part of the current diesel-operated equipment with electric versions;

- Reduction in CO2 emissions compared to the base year of 2024;

- Upgrading the Port Community System (PCS) and advancing digital logistics capabilities.

Measures

- Integration of Electric Equipment in Port Operations

- Enhancing the Port’s Renewable Energy Share

- Reduction of CO2 emissions

- -

- E_consumption is the annual electricity consumption in megawatt-hours (MWh);

- -

- EF is the emission factor in tons of CO2 equivalent per MWh (t CO2e/MWh).

- N = number of machines;

- H = annual operating hours per machine;

- C = average fuel consumption in liters per hour (L/h);

- EF = emission factor for diesel fuel (kg CO2/L).

- Port Community System (PCS)

- I.

- Integration with Customs and Logistics Systems in Real Time

- II.

- Implementation of Automated Resource Planning and Predictive Analytics

- III.

- Adding a Green Management and ESG Reporting Module

Economic Feasibility and Cost–Benefit Analysis of Phase I (2026–2030)

- Capital Expenditure and Asset Monetization

- Operational Expenditure Savings

- Return on Investment

- Almost zero fuel costs for replaced equipment;

- Significantly reduced electricity bills;

- Full ownership of solar assets with a remaining useful life of 20+ years [92].

Critical Risks and Mitigation Strategies

4.2.2. The Second, Ambitious Phase 2030–2038

Key Objectives

- Achieve complete electrification of port equipment;

- Provide full OPS coverage for ships at berth;

- Ensure that renewable energy sources fully supply the port’s energy demand;

- Achieve full decarbonization of port operations (net-zero port).

Measures

- Integration of Electric Equipment in Port Operations

- Onshore Power Supply System

- Enhancing the Port’s Renewable Energy Share

- Mobile cranes work about 2000 h a year, which covers the transshipment season and planned downtimes due to service or weather conditions [123];

- For terminal vehicles, we used typical data for city fleet cars, about 10,000 km per year [117];

- Specialized equipment like the Dulevo D.Zero2 sweeper is planned for around 1500 working hours per year, which covers the daily cleaning of operating surfaces [114].

- Net-Zero Port

Economic Feasibility and Cost–Benefit Analysis of Phase II (2030–2038)

- Capital expenditure and asset monetization

- EUR 20.0 million indicative investment for infrastructure for electricity supply on land (OPS), after a 20% grant from the Montenegrin Eco-Fund;

- EUR 8.3 million indicative investment for the purchase of new electric mobile equipment and crane modifications, after a 20% subsidy from the Eco-Fund at a market price of EUR 10.4 million;

- EUR 1.3 million for an additional 3.0 GWh/year of the photovoltaic system (the subsidy is already included in the offered price);

- EUR 0.5 million to upgrade the Port Common System (PCS) to enable real-time monitoring.

- Operational Expenditure Savings

- Fuel and lubricant savings of around EUR 171,529 euros [85].

- The expanded solar capacity fully covers the port’s projected base demand generating annual grid savings of EUR 286,000 at a reference tariff of EUR 0.13/kWh [93].

- With 0.8 GWh/year of excess solar production and additional energy from the grid, the OPS system is expected to serve vessels at a competitive tariff of EUR 0.175/kWh (including VAT), which brings an annual revenue of approximately EUR 140,000 in a moderate berth utilization scenario of 40%.

- Return on investment

- Beyond Economic Metrics—The Value of Decarbonization

- Uncertainty and adaptive management

- Actual costs of acquiring equipment, including potential deviations from estimated prices due to inflation, exchange rate changes or disruptions in global supply chains;

- Actual berth utilization rates and vessel demand for operational services, especially shore power supply (OPS) services, which are key to generating revenue;

- The actual level and dynamics of the profitability of subsidies, including the risk that EU funds (e.g., IPA III, CEF) will not be paid within the stipulated period or in full, which could lead to a temporary liquidity gap;

- Potential need for additional sources of financing, such as credit through the European Investment Bank (EIB), if there is a gap between planned and actually available funds.

Critical Risks and Mitigation Strategies

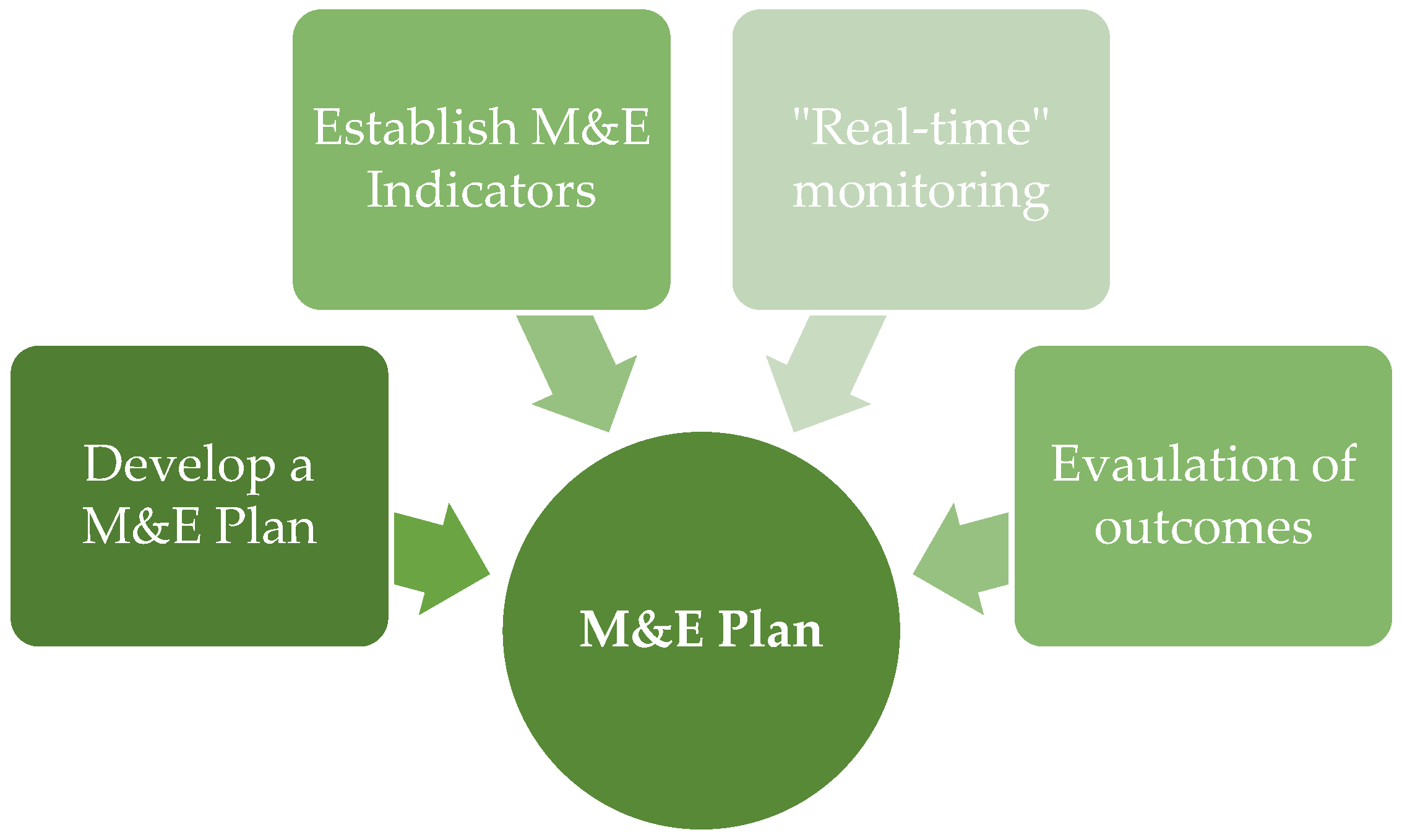

4.3. Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

4.3.1. Develop a Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

4.3.2. Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators

4.3.3. “Real-Time” Monitoring

4.3.4. Evaluate Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Alignment and Regulatory Implications

5.2. Economic Feasibility: Beyond Payback Periods

5.3. Global Supply Chains

5.4. Socio-Economic and Community Impact

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Family | Unit | Brand and Type | Year of Manufacture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ELECTRIC FORKLIFT 1.8 T | 2 | HELI electric CPD-HT2 1.8 t | 2019 |

| 2 | ELECTRIC FORKLIFT 2 T | 4 | STILL electric RX 20-20 2.0 t | 2020 |

| 3 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 2 | STILL RX 70-30 triplex-duga 4200 diesel 3.0 t | 2012 |

| 4 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 1 | STILL RX 70-30 triplex-duga 4200 diesel DPF 3.0 t | 2012 |

| 5 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 2 | NETLIFT FG 30t-m/GF3 triplex 4800 diesel 3.0 t | 2020 |

| 6 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 2 | HELI CPCD30-WS1H diesel 3.0 t | 2020 |

| 7 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 3 | STILL RX 70-30/600 Hybrid Drive 3.0 t | 2024 |

| 8 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 1 | HANGCHA CPCD 35N-RW13 diesel 3.5 t | 2008 |

| 9 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 3 T | 1 | LINDE H35D | 2008 |

| 10 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 6 T | 1 | STEINBOCK BOSS H60 diesel 6.0 t | 2000 |

| 11 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 6 T | 1 | HELI CPCD60-P2 diesel 6.0 t | 2020 |

| 12 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 12.5 T | 1 | LITOSTROJ V 12,5IH simplex 14,800 diesel 12.5 t | 1987 |

| 13 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 16 T | 1 | KALMAR DCG160-12T 16 t | 2019 |

| 14 | DIESEL FORKLIFTS 25 T | 1 | HELI CPCD250-VZ2-12 III diesel 25 t | 2020 |

| 15 | 42T FORKLIFT WITH SPREADER | 1 | LANCER BOSS G4212GPCH duplex 56,300 42 T | 1998 |

| 16 | REACHSTACKER 45 T | 1 | KALMAR DRU450-6S REACHSTACKER | 2020 |

| 17 | 80T MOBILE CRANES | 1 | DEMAG AC80-1 80 T | 2000 |

| 18 | PORT MOBILE CRANE | 1 | LIEBHERR LHM550 144 T | 2011 |

| 19 | PORT MOBILE CRANE | 1 | LIEBHERR LHM420 124 T | 2020 |

| 20 | LOADERS | 2 | CATERPILLAR 950 H 3.5 m3 | 2008 |

| 21 | LOADERS | 1 | CATERPILLAR 966GC 4.2 m3 | 2021 |

| 22 | LOADERS | 2 | CATERPILLAR 950GC 3.5 m3 | 2022 |

| 23 | LOADERS | 1 | CATERPILLAR 966GC 4.2 m3 | 2022 |

| 24 | LOADERS | 1 | CATERPILLAR 216B II SKID STEER 0.4 m3 | 2008 |

| 25 | LOADERS | 1 | CATERPILLAR 236D3 Skid Steer Loader | 2023 |

| 26 | LOADERS | 2 | KOMATSU WA200PZ-6 1.5 m3 | 2011 |

| 27 | LOADERS | 1 | KOMATSU WA380-6 3.6 m3 | 2011 |

| 28 | LOADERS | 1 | KOMATSU SK1026-5 SKID STEER 0.5 m3 | 2011 |

| 29 | LOADERS | 1 | HYUNDAI HL770-9A 4.1 m3 | 2013 |

| 30 | LOADERS | 1 | HYUNDAI HL730-9 1.9 m3 | 2024 |

| 31 | MATERIAL HANDLER | 1 | SENNEBOGEN 825.0.1915 MATERIAL HANDLER | 2013 |

| 32 | MATERIAL HANDLER | 1 | SENNEBOGEN 825.0.2541 MATERIAL HANDLER | 2018 |

| 33 | MATERIAL HANDLER | 1 | SENNEBOGEN 825.0.2665 MATERIAL HANDLER | 2020 |

| 34 | MATERIAL HANDLER | 1 | SENNEBOGEN 835.0.3397 MATE RIAL HANDLER | 2024 |

| 35 | TRACTOR TRUCK | 3 | IVECO STRALIS 460 ECO | 2012 |

| 36 | TRACTOR TRUCK | 2 | MERCEDES ACTROS 1844 LS 4X2 | 2008 |

| 37 | TRACTOR TRUCK | 1 | MERCEDES ACTROS 1850 LS 4X2 | 2003 |

| 38 | TRACTOR TRUCK | 2 | MAN TGS 18 400 | 2015 |

| 39 | TRACTOR TRUCK | 2 | MERCEDES ACTROS 1844 LS 4X2 | 2008 |

| 40 | TRUCK SWEEPER | 1 | MERCEDES BENZ ATEGO 1318 LKO FAUN VIAJET | 2008 |

| No. | Family | Unit | Year of Manufacture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PASSENGER VEHICLE | 1 | 2012 |

| 2 | PASSENGER VEHICLE | 2 | 2012 |

| 3 | PASSENGER VEHICLE | 1 | - |

| 4 | PASSENGER VEHICLE | 1 | 2010 |

| 5 | PASSENGER VEHICLE | 1 | - |

| 6 | PASSENGER VEHICLE | 1 | 2007 |

| 7 | SHUTTLE BUS | 1 | 2023 |

References

- Acciaro, M. Energy management in seaports: A new role for port authorities. Energy Policy 2014, 71, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satır, T.; Doğan-Sağlamtimur, N. The protection of marine aquatic life: Green Port (EcoPort) model inspired by Green Port concept in selected ports from Turkey, Europe and the USA. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2018, 6, 120. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325920099_The_Protection_of_Marine_Aquatic_Life_Green_Port_EcoPort_Model_inspired_by_Green_Port_Concept_in_Selected_Ports_from_Turkey_Europe_and_the_USA (accessed on 28 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bodansky, D. The Legal Character of the Paris Agreement. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2016, 25, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, W.P.; Castro, P.; Pickering, J.; Bhasin, S. Conditional nationally determined contributions in the Paris Agreement: Foothold for equity or Achilles heel? Clim. Policy 2020, 4, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarkamand, S.; Wooldridge, C.; Darbra, R.M. Review of Initiatives and Methodologies to Reduce CO2 Emissions and Climate Change Effects in Ports. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 17, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C. Desafios de Segurança e Ambiente nas Áreas Portuárias. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/24110 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Lee, C.Y.; Song, D. Ocean Container Transport in Global Supply Chains: Overview and Research Opportunities. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2017, 95, 442–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trellis. Maritime Shipping Could Triple by 2050. How Will the Industry Decarbonize? Available online: https://trellis.net/article/maritime-shipping-could-triple-2050-how-will-industry-decarbonize/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

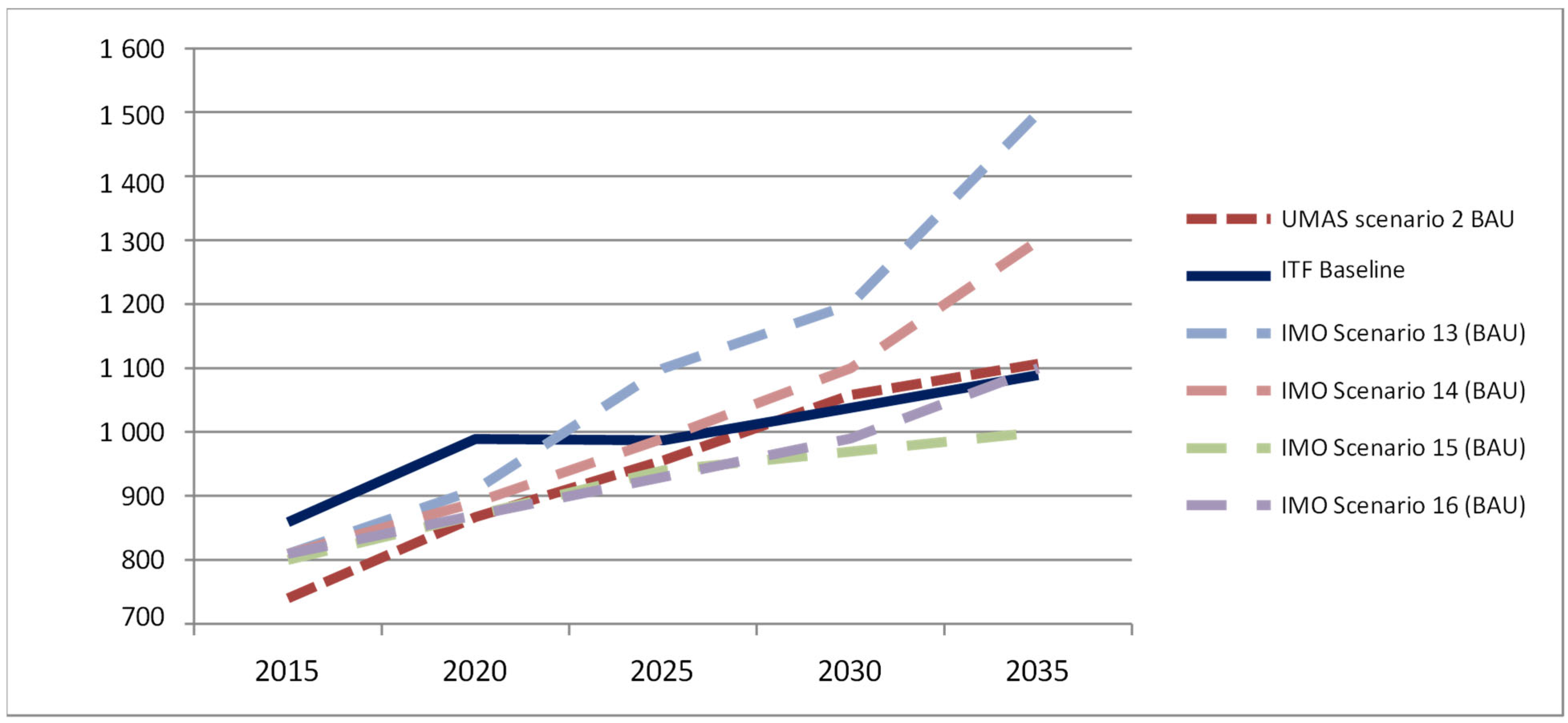

- OECD/ITF. Different Projections for Shipping’s CO2 Emissions to 2035. In Decarbonising Maritime Transport; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). IMO’s Work to Cut GHG Emissions from Ships. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/Cutting-GHG-emissions.aspx (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Paris Agreement; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO). Top 10 Environmental Priorities 2024; ESPO: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://www.espo.be/publications/top-10-environmental-priorities-2024 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Ringbom, H. The EU Maritime Transport Policy and Maritime Law; Brill | Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brunila, O.; Ruokonen, T.; Inkinen, T. Sustainable Small Ports: Performance Assessment Tool for Management, Responsibility, Impact, and Self-Monitoring. J. Shipp. Trade 2023, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, A.; Van Assche, K.; Hornidge, A.K.; Văidianu, N. Land-Sea Interactions and Coastal Development: An Evolutionary Governance Perspective. Mar. Policy 2020, 112, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čerin, P.; Beškovnik, B. Enhancing Sustainability through the Development of Port Communication Systems: A Case Study of the Port of Koper. Sustainability 2024, 16, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luka Koper, d.d. Sustainability Strategy 2022–2027; Luka Koper: Koper, Slovenia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Caramuta, C.; Giacomini, C.; Longo, G.; Padoano, E.; Zornada, M. Integrated Evaluation Methodology and its Application to Freight Transport Policies in the Port of Trieste. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 30, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Port of Gothenburg. Sustainable Port 2024—Port of Gothenburg Sustainability Report; Port of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://www.portofgothenburg.com/globalassets/dokument/port_of_gothenburg_sustainableport2024_eng.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Port of Antwerp-Bruges. Electrification Strategy and Equipment Conversion Costs; Port of Antwerp-Bruges: Antwerp, Belgium, 2022; pp. 7–8. Available online: https://www.portofantwerpbruges.com/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Port of Rotterdam. Port Authority Invests in Digitalisation and Sustainability. Available online: https://www.portofrotterdam.com/en/port-future/digitisation (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Bichou, K. Linking Theory with Practice in Port Performance and Benchmarking. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2012, 4, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaleb, F.; Mabrouki, C.; Semma, A. Key Performance Indicators Evaluation and Performance Measurement in Dry Port-Seaport System: A Multi Criteria Approach. J. ETA Marit. Sci. 2015, 3, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensieri, S.; Viti, F.; Moser, G.; Serpico, S.B.; Maggiolo, L.; Pastorino, M.; Solarna, D.; Cambiaso, A.; Carraro, C.; Degano, C.; et al. Evaluating LoRaWAN Connectivity in a Marine Scenario. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Nie, A.; Chen, J.; Pang, C.; Zhou, Y. Transforming Ports for a Low-Carbon Future: Innovations, Challenges, and Opportunities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 264, 107636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.; Zaslavsky, A.; Christen, P.; Georgakopoulos, D. Context Aware Computing for the Internet of Things: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 414–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Tai, N.; Wu, J. Application Prospect and Key Technologies of Digital Twin Technology in the Integrated Port Energy System. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 1044978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lee, P.T.-W.; Yang, Z. Digital Technologies and Real-Time Operations in Smart Ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmokaitė, I. Tracing Innovation Practices in Seaports: The Ports of Klaipeda and Stockholm as Case Studies. Master’s Thesis, University of Turku, Turku, Finland, 2015. Available online: https://www.utupub.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/116130/Igne_Stalmokaite_masters-thesis_2015.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Elsayeh, M.E.; Hubbard, N.J.; Tipi, N.S. An Assessment of Hub-Ports Competitiveness and Its Impact on the Mediterranean Container Market Structure. Available online: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/11838/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Gularte Quintana, C.; Munhoz Olea, P.; Raggi Abdallah, P.; Costa Quintana, A. Port Environmental Management: Innovations in a Brazilian Public Port. Rev. Adm. Innov. 2016, 13, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, L.C.; Caceres, E.O.; Campo, B.C.; Bortoluzzi, E.C.; Neckel, A.; Moreno-Ríos, A.L.; Dal Moro, L.; Oliveira, M.L.S.; de Vargas Mores, G.; Ramos, C.G. Advancing Sustainability: Effective Strategies for Carbon Footprint Reduction in Seaports across the Colombian Caribbean. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung Ee Yong, J. Agent-Based Model for Sustainable Equipment Expansion with CO2 Reduction of a Container Port. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 2017. Available online: http://eprints.utm.my/79594/1/JonathanChungEePFKM2017.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Motau, I.G. An Assessment of Port Productivity at South African Container Port Terminals. Ph.D. Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, S.; Kim, D.; Park, K. Artificial Intelligence Based Smart Port Logistics Metaverse for Enhancing Productivity, Environment, and Safety in Port Logistics: A Case Study of Busan Port. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes Salmon, R.A. Nivel de Conocimiento en Regulaciones, Sistemas Ecoamigables y Conservación Medio Ambiental en los Recintos Portuarios Estatales de Ciudad de Panamá. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Panamá, Panama City, Panama, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes Constante, J. International Case Studies and Good Practices for Implementing Port Community Systems; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 12–20. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Heilig, L.; Lalla-Ruiz, E.; Voß, S. Digital transformation in maritime ports: Analysis and a game theoretic framework. Comput. Ind. 2017, 89, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM; Maersk. Transforming Global Trade with Blockchain Technology. IBM. 2021. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/case-studies/maersk-blockchain-tradelens (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Martide. Everything You Need to Know About Smart Ports. Available online: https://www.martide.com/en/blog/everything-you-need-to-know-about-smart-ports (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Luoma, K.E.; Vantola, J.R.; Lehikoinen, M.A. Towards a Sustainable Small Port—Perspectives of Boaters and Port Actors. Available online: https://www.merikotka.fi/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Towards-a-sustainable-small-port_report.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Port of Bar Privatization. Available online: https://www.ebrd.com/home/work-with-us/projects/psd/49335.html#project-description1 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- SUPAIR Project. SUPAIR Project; Interreg ADRION: Trieste, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://supair.adrioninterreg.eu/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Port of Bar Holding Company. Action Plan for Sustainable and Low-Carbon Port of Bar. SUPAIR Project. 2019. Available online: https://supair.adrioninterreg.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Action-Plan-for-a-Sustainable-and-Low-carbon-Port-of-Bar.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL); IMO: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://portalcip.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/MARPOL-INGLES.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2019/883 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Port Reception Facilities for the Delivery of Waste from Ships. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L151, 116–142. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Status of IMO Treaties—Comprehensive Information; IMO: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/About/Conventions/StatusOfConventions/Status%20-%202022%20(2).pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- European Commission. Delivering the European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- European Commission. ‘Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality. In COM(2021) 550 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0550 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). NDC Synthesis Report; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Technology Framework Under the Paris Agreement; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries: Aggregate Trends Updated; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality (European Climate Law). Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L243, 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Stepping up Europe’s 2030 Climate Ambition: Investing in a Climate-Neutral Future for the Benefit of Our People. In COM(2020) 562 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1056 Establishing the Just Transition Fund. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L231, 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation Establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. In COM(2021) 564 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2003/87/EC Establishing a Scheme for Greenhouse Gas Emission Allowance Trading within the Community (EU ETS Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, L275, 32. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Renewable Energy Directive II). Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L328, 82. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2014/94/EU on the Deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, L307, 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation on the Deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure. In COM(2021) 559 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Environment; No. 52/16, 54/16, 13/18, 76/20; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2019.

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Environmental Impact Assessment; No. 80/05, 40/10, 27/13, 53/14, 52/16; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2018.

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment; No. 80/05, 73/10, 40/11, 27/13, 52/16; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2018.

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control; No. 17/19; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2019.

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Environmental Noise Protection; No. 28/11; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2011.

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Air Protection; No. 25/10; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2010.

- Ministry of Ecology, Spatial Planning and Urbanism of Montenegro. Law on Industrial Emissions; No. 17/19; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2019.

- Government of Montenegro. Transport Development Strategy of Montenegro 2020–2035; Ministry of Capital Investments: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2020.

- Government of Montenegro. Zakon o Energetskoj Efikasnosti; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.me/dokumenta/8e55f340-191c-4a0f-a321-26f6ccd25c52 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Government of Montenegro. Strategija Razvoja Energetike Crne Gore do 2030. Godine; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.me/dokumenta/eac811f8-4b13-46ce-97c4-412b8d1ebb8a (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Government of Montenegro. Nacionalna Strategija Održivog Razvoja do 2030. Godine; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.me/dokumenta/67dc487e-097d-41d2-8fd5-7827a19a1f5a (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Government of Montenegro. Strategija Razvoja Pomorske Privrede 2020–2030. sa Akcionim Planom 2020–2021; Official Gazette of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.me/dokumenta/2b69a6ae-e751-4a25-8de0-48b564e2a38d (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Global Ports Holding. Acquisition of Port of Adria Bar Tender. Available online: https://www.portstrategy.com/global-ports-wins-tender-for-port-of-bar/202186.article (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Luka Bar. Komparativne Prednosti Luke Bar. Available online: https://lukabar.me/komparativne-prednosti-luke-bar/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- SeeNews. Montenegro Eyes Buyback of Port of Adria from GPH. 2024. Available online: https://seenews.com/news/montenegro-eyes-buyback-of-port-of-adria-from-gph-1267463 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Global Ports Holding. Port of Adria—Global Ports Holding. Available online: https://www.globalportsholding.com/our-ports/port-of-adria (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Wikipedia. Rail Transport in Montenegro. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rail_transport_in_Montenegro (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Hellenic Petroleum. Jugopetrol AD. Available online: https://www.helleniqenergy.gr/en/about-us/international-presence/jugopetrol (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Luka Bar AD. Plan Integriteta “Luka Bar” AD—Bar 2024; Luka Bar: Bar, Montenegro, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro Business. Luka Bar Seeks Consulting Firm for Due Diligence on Port of Adria Acquisition. 2024. Available online: https://montenegrobusiness.eu/montenegro-business-recent-economy-port-of-bar-2/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Bar Cruise Port. General Information. Available online: https://www.barcruiseport.com/general-information (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Luka Bar AD. Biznis Plan “Luka Bar” AD—Bar za 2025. Godinu; Luka Bar: Bar, Montenegro, 2025. [Google Scholar]

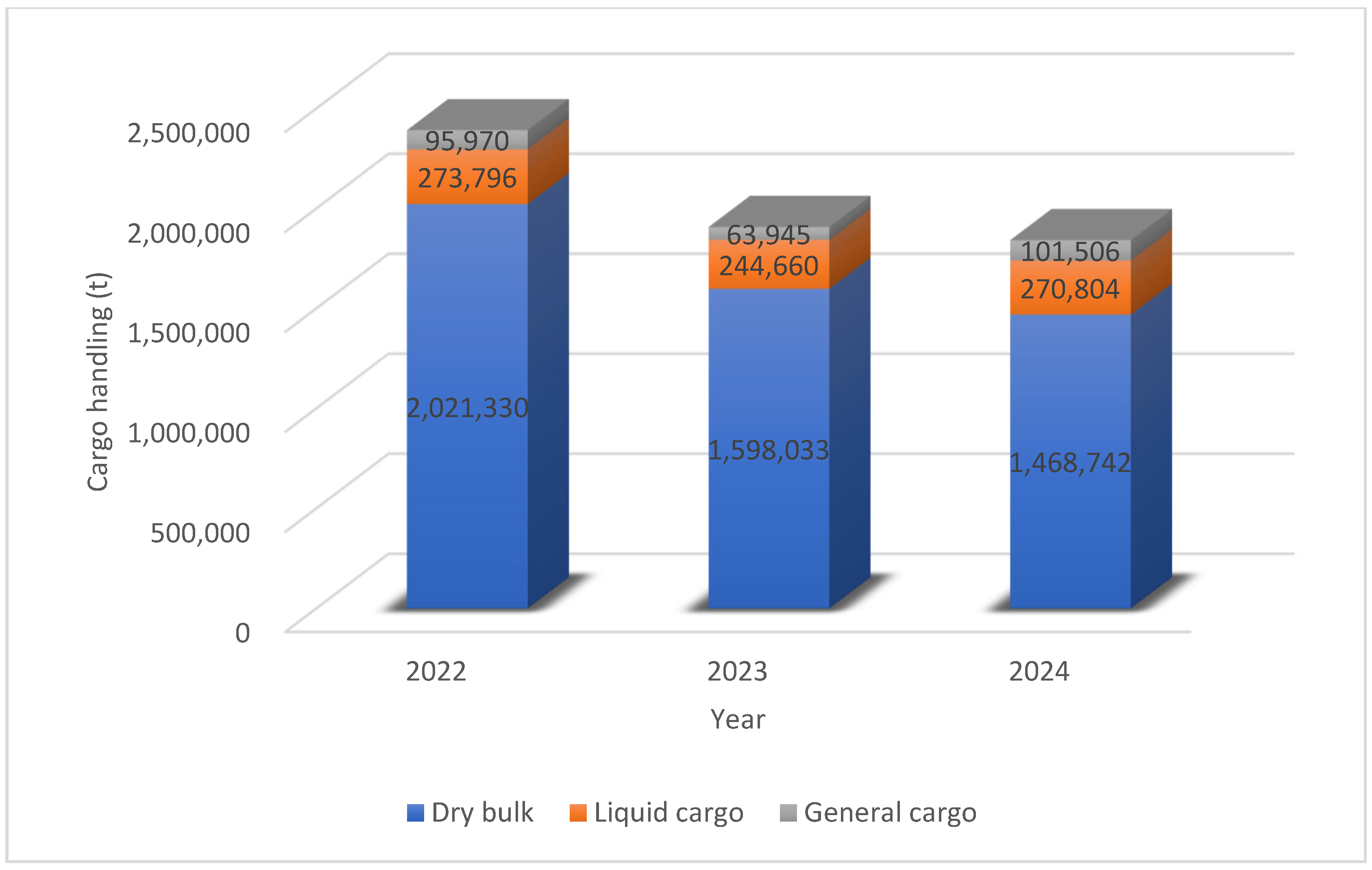

- Luka Bar AD. Izvještaj o Poslovanju za Period I–XII 2022; Luka Bar: Bar, Montenegro, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luka Bar AD. Izvještaj o Poslovanju za Period I–XII 2023; Luka Bar: Bar, Montenegro, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luka Bar AD. Izvještaj o Poslovanju za Period I–XII 2024; Luka Bar: Bar, Montenegro, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Luka Bar AD. Lučka mehanizacija. Available online: https://lukabar.me/lucka-mehanizacija/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Hyster. Hyster J10–18XD Product Brochure; Hyster-Yale Materials Handling, Inc.: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.hyster.com/en-sg/asia-pacific/4-wheel-electric-forklift-trucks/j10-18xd/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Forkliftaction. Market Pricing for Electric Forklifts—Europe 2024 Overview. Available online: https://www.forkliftaction.com (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- BYD Europe. BYD ECB30D Product Datasheet; BYD Company Ltd.: Shenzhen, China, 2022; Available online: https://bydforklift.com/uk/model/counterbalance-forklift-ecb30-35-45-50/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Volvo Construction Equipment. Volvo L25 Electric—Product Brochure; Volvo CE: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2024; p. 3. Available online: https://www.volvoce.com/europe/en/products/electric-machines/l25-electric-gen3/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Machinery Trader. Volvo L25 Electric For Sale—2024 Listings. Available online: https://www.machinerytrader.com/listings/volvo-l25-electric (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Elektroprivreda Crne Gore. Solari 500+ za Profitabilnije Poslovanje i Čistiju Okolinu. Available online: https://epcg-sg.com/lat/solari-3000-i-solari-500/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Elektroprivreda Crne Gore. Informational Table for Customers. Available online: https://epcg-sg.com/lat/solari-3000-i-solari-500/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Port of Bar. Development Projects. Available online: https://lukabar.me/razvoj/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Continuous Energy Improvement in Motor Driven System; Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/04/f15/amo_motors_guidebook_web.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- World Resources Institute; World Business Council for Sustainable Development. GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance: An Amendment to the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard; WRI/WBCSD: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/scope_2_guidance (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Climatiq. Emission Factor: Electricity Supplied from Grid—Montenegro (0.405 kg CO2 e/kWh). Available online: https://www.climatiq.io/data/emission-factor/e3f9bdb0-ea1c-448a-9a56-f28664d9fa1e (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Pashkevich, N.; Haftor, D.; Karlsson, M.; Chowdhury, S. Sustainability through the Digitalization of Industrial Machines: Complementary Factors of Fuel Consumption and Productivity for Forklifts with Sensors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Emission Factors for Greenhouse Gas Inventories; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 7–9. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/documents/ghg-emission-factors-hub.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Luka Bar. Port Community System. Available online: https://lukabar.me/port-community-system/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). The European Environment—State and Outlook 2020: Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; pp. 47–56. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/soer-2020 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Transport and Trade Facilitation; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/dtltlb2021d1_en.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Port of Bar. Port of Bar JSC Signed a Contract with Liebherr-International AG for Procurement of a New Mobile Harbour Crane. Available online: https://lukabar.me/en/saopstenje-za-javnost-11/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Liebherr Maritime. LHM E-Drive Integration—Technical Bulletin and Implementation Overview; Liebherr-International AG: Rostock, Germany, 2024; p. 3. Available online: https://www.liebherr.com/es-int/n/electric-drive-on-the-rise-203328-3935641 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- GlobalSources.com. Reach Stacker—45 Ton Electric Container Handler. Available online: https://www.globalsources.com/Stacker/Reach-stacker-1167114649p.htm (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Sennebogen. SENNEBOGEN 825 E Electro Battery—Material Handler; Sennebogen GmbH: Straubing, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.sennebogen.com/en/products/material-handler/sennebogen-825/sennebogen-825-e-electro-battery (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Mascus. Used SENNEBOGEN 825 Material Handlers for Sale. Available online: https://www.mascus.com/sennebogen%20825%20/+/1,relevance,search.html (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Sennebogen. Green Efficiency—Battery Powered Material Handling; Internal Technical Report; Sennebogen GmbH: Straubing, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Volvo Trucks North America. Volvo VNR Electric Specifications; Volvo Group: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.volvotrucks.us/trucks/vnr-electric/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Volvo Trucks North America. Volvo VNR Electric Product Brochure (MY2024); Volvo Group: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ACT Research. Battery Electric Truck Total Cost of Ownership Report; ACT Research Co.: Columbus, IN, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.actresearch.net/consulting/special-projects/commercial-vehicle-decarbonization-forecast-reports (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- CALSTART. Voucher Incentive Programs: A Tool for Zero-Emission Commercial Vehicle Deployment; CALSTART: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://calstart.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Voucher-Incentive-Programs-A-Tool-for-Zero-Emission-Commercial-Vehicle-Deployment_new.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Dulevo International. D.Zero2 Electric Street Sweeper—Technical Data; Dulevo S.p.A.: Piacenza, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.dulevo.com/products/street-sweepers/new-dulevo-d-zero2-1/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Hydromech.eu. Dulevo D.Zero2 Electric Sweeper Product Listing. Available online: https://hydromech.eu/en/products/machines/street-sweepers/-zamiatarka-samojezdna-dulevo-d6-23472.html (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- VOC Port Authority. Draft Performance Linked Upfront Tariff Schedule for Mechanised Handling at Berth No. 9; VOC Port: Visakhapatnam, India, 2023; p. 25. Available online: https://www.vocport.gov.in/port/UserInterface/PDF/Draft%20Performance%20Linked%20Upfront%20Tariff%20Schedule.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Dacia. Spring Electric—Technical Specifications; Renault Group: Boulogne-Billancourt, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.dacia.fr/gamme-electrique-et-hybride/spring-citadine/comparateur-specifications.html (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH). Onshore Power Supply: Market Brief and Guidance; IAPH: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; p. 12. Available online: https://www.iaphworldports.org/n-iaph/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IAPH_ANNUAL_REPORT_2021-2022.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO). Environmental Report 2023: Trends in Port Environmental Management; ESPO: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://www.espo.be/media/ESPO%20Environmental%20Report%202023.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Review of Maritime Transport 2023; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2023 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO). Environmental Report 2023; ESPO: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://www.espo.be/news/espos-environmental-report-2023-climate-change-aga (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Shore Power Technology Assessment at U.S. Ports; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ports-initiative/shore-power-technology-assessment-us-ports (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Liebherr Group. Technical Data—Mobile Harbour Crane LHM 550; Liebherr-International AG: Rostock, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.liebherr.com/en-int/p/lhm550-5391546 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Kalmar. Kalmar Electric Reachstacker Specifications; Cargotec Corporation: Helsinki, Finland, 2024; Available online: https://www.kalmarglobal.com/equipment/reachstackers/electric-reachstacker/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- European Commission (EC). Fit for 55 Package: Climate Neutrality by 2050. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Energy Infrastructure: Current TEN-T Ports Equipped with Shore-Side Electricity. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/sustainability-of-europes-mobility-systems/energy-infrastructure (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Initial IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships; IMO: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Environment/Documents/annex/MEPC%2080/Annex%2015.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Better Criteria for Better Evaluation: Revised Evaluation Criteria Definitions and Principles for Use; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2019/12/better-criteria-for-better-evaluation_f7a307eb/15a9c26b-en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Carbon Trust. Grow to Zero: How Target-Setting Standards Can Incentivize Responsible Growth While Enabling Global Decarbonization; Carbon Trust: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.carbontrust.com/our-work-and-impact/guides-reports-and-tools/grow-to-zero (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Review of Maritime Transport 2022; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2022_en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH). Digital Twins in Ports: A Call for Action; IAPH: Tokyo, Japan, 2023; pp. 6–12. Available online: https://www.sustainableworldports.org/wp-content/uploads/IAPH-2023-Digital-Twins-in-Ports.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- World Bank. Accelerating Digital Critical Action to Strengthen the Resilience of the Maritime Supply Chain; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/773741610730436879-0190022021/original/AcceleratingDigitalizationAcrosstheMaritimeSupplyChain.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

| Key Measure | Environmental Impact | Port Operations Optimization | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical and Regulatory Framework | Eco-friendly practices | Integration of “green” criteria | - |

| Designing a phased approach | Sustainability | Digitalization and modernization | Long-term investment attractiveness |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Continuous improvement | Real-time decision making | Budgeting and resource management |

| Focus Area | Energy Efficiency Actions/Measures |

|---|---|

| Across all consumption sectors |

|

| For large energy consumers |

|

| Additional measures for small and medium sized enterprises |

|

| Focus Area | Key Actions/Measures |

|---|---|

| Investment support |

|

| Sun radiation |

|

| Strategic Goal | Operation Goal | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing the contribution of the maritime industry and related activities to the overall economic development | Achieving sustainable growth and competitiveness in the port sector |

|

| Development of maritime industry is based on the principles of the green economy | Create prerequisites in the public and private maritime sector for economic growth based on the principles of the green economy |

|

| Law/Strategy | Specific Benefits for the Port of Bar |

|---|---|

| Law on Energy Efficiency |

|

| Energy Development Strategy of Montenegro until 2030 |

|

| National Strategy for Sustainable Development until 2030 |

|

| Town | Road | Railway | Town | Road | Railway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgrade | 530 km | 476 km | Prishtina | 551 km | 651 km |

| Novi Sad | 580 km | 632 km | Szeged | 759 km | 797 km |

| Subotica | 691 km | 653 km | Budapest | 875 km | 826 km |

| Skopje | 442 km | 642 km | Bucharest | 940 km | 926 km |

| Type | Length (m) | Water Depth (m) | Sea Level (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Voluica” quay | 554.4 | 10.7–14 | 3 |

| “Old” quay | 280 | 3.0–7.2 | 2.5 |

| New petroleum berth | 66 | 13.5 | 2.5 |

| Berth 26 (pier II/pier III) | 239 | 10.5 | 3 |

| Southern quay of pier iii | 136 | 8.1 | 3 |

| Passenger terminal | 332 | 5.9 | 2 |

| Type | Model | Quantity | Capacity | Battery Type | Charging Time | Unit Price (EUR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy-duty Forklift | Hyster J10–18XD | 3 | 10–18 tons | Lithium ion | ~2 h | 115,000 | [87,88] |

| BYD ECB30D | |||||||

| Medium-duty Forklift | Hyster J10–18XD | 5 | 3 tons | Lithium iron phosphate | ~2 h | 38,000 | [88,89] |

| Type | Model | Quantity | Bucket Capacity | Battery Type | Charging Time | Unit Price (EUR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compact e-loader | Volvo L25 Electric | 8 | 1.17 m3 | Lithium ion | ~2 h | ~125,000 | [90,91] |

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Annual electricity cost (2024) | EUR 608,785.79 | [85] |

| Reference system capacity (per unit) | 10 kW | [93] |

| Average annual production (per 10 kW system) | 16,080 kWh | [93] |

| Required total annual production | 3,000,000 kWh (3 GWh) | Author calculation |

| Number of 10 kW systems required | 187 units | Author calculation |

| Total installed capacity | 1.87 MW | Author calculation |

| Estimated required roof area | ~13,000 m2 | [82,94]. |

| Unit system cost (10 kW) Eko fond subsidy (20%) included | EUR 6988.95 | Unpublished data, EPCG & Solar Gradnja interview, 2025 |

| Total investment Eco-fund subsidy (20%) included | EUR 1,306,938.65 | Author calculation |

| Payment period | Up to 10 years | [92] |

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Annual electricity consumption (2024) | ~3.7 GWh | [85] |

| Estimated additional consumption (New e-equipment) | ~0.3 GWh | [93] |

| Total projected consumption | ~4.0 GWh | [93] |

| Annual electricity cost (2024) | EUR 608,785.79 | Author calculation |

| Solar capacity to be installed | 187 units × 10 kW | Author calculation |

| Total energy produced by solar system | ~3.0 GWh/year | Author calculation |

| Estimated coverage with solar (post-electrification) | ~75% | [82,94] |

| Investment cost (with subsidy included) | EUR 1,306,938.65 | Author calculation, based on unpublished data (EPCG & Solar Gradnja interview, 2025) |

| Estimated annual savings (at €0.13/kWh) | ~ EUR 390,000 | Author calculation |

| Payback period | ~3.35 years | [92] |

| Ownership & energy independence after payback | 100% of solar-produced energy |

| Type | Model | Quantity | Capacity | Battery Type | Charging Time | Unit Price (EUR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy-duty Forklift | Hyster J10–18XD | 3 | 10–18 tons | Lithium-ion | ~2 h | 115,000 | [87,88] |

| Medium-duty Forklift | BYD ECB30D | 7 | 3 tons | Lithium iron phosphate | ~2 h | 38,000 | [88,89] |

| Compact e-loader | Volvo L25 Electric | 6 | 1.17 m3 | Lithium-ion | ~2 h | ~125,000 | [90,91] |

| Reachstacker | Kalmar Electric Reachstacker | 1 | 45 t | Lithium-ion | ~6 h | ~360,000 | [106] |

| Material Handler | Sennebogen 825 E | 4 | 28–30.4 t | Li-ion battery + dual power | ~4–6 h | 300,000–350,000 | [107,108,109] |

| Type | Model | Quantity | GVWR | Battery Type | Charging Time | Unit Price (EUR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volvo Truck | VNR Electric | 10 | 37,200 kg | 100% Battery Electric | 90 min DC fast charge | 366,500–412,300 | [110,111,112,113] |

| Dulevo International | Dulevo D.Zero2 Electric | 1 | ~25,200 m2/h | Li-ion battery | 5.5 h | 281,800 | [114,115] |

| Year | Model | Retrofit Kit (EUR) | Software and Integration (EUR) | Total Upgrade Cost (EUR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | LHM 420 (124 t) | 1,000,000–1,300,000 | 200,000–300,000 | 1,200,000–1,600,000 | [20,105] |

| 2025 | LHM 550 (144 t) | 600,000–900,000 | 150,000–200,000 | 750,000–1,100,000 | [105,116] |

| Model | Price (EUR) | Battery (kWh) | Range | Power (kW) | Quantity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dacia Spring | ~20,000–22,000 | 26.8 | 230 km | 33 kw | 6 | [117] |

| Item | Description | Estimated Cost (€) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of berths covered by OPS | Bulk carriers, general cargo and passenger ships | 5 berths (estimate) | [118,119] |

| Average cost per MW | Includes shore connection, substations, converters, civil works | EUR 2–4 million per MW | [118,119,120] |

| Estimated capacity per berth | Bulk/general cargo: ~2 MW; passenger: 3–4 MW → avg. 2–2.5 MW per berth | ~10–12 MW total | [118,119] |

| Civil works & infrastructure | Cable trenches, ducting, network upgrades, SCADA, EMS software (included) | Included in MW cost | [118,120] |

| Total estimated investment | Complete OPS coverage for Port of Bar (5 berths) | EUR 20–30 million | [118,119,120] |

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Annual electricity consumption not covered by Phase I solar | ~1.0 GWh | Authors’ calculation (2025) |

| Estimated additional consumption (new e-equipment) | ~1.2 GWh | [122] |

| Total projected consumption (Phase II) | ~2.2 GWh | Combined estimation |

| Planned additional solar capacity to be installed | ~3.0 GWh/year | EPCG, 2025—New project outline; Solari 500+ program expansion |

| Total energy produced by new solar system | ~3.0 GWh/year | [93] |

| Estimated coverage with additional solar (Phase II) | ~100% (including reserve) | Authors’ calculation |

| Investment cost (with subsidy included) | EUR 1,306,938.65 | Author calculation, based on unpublished data (EPCG and Solar Gradnja interview data, 2025) |

| Estimated annual savings (at €0.13/kWh) | ~€286,000 | Authors’ calculation |

| Payback period | ~4–5 years (estimate) | Authors’ calculation |

| Ownership and energy independence after payback | 100% of additional solar-produced energy | [92] |

| Performance Indicator | Target Value by 2030 | Method of Measurement | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total CO2 emissions | −1500 tCO2 compared to 2024 baseline | Annual emission inventory report | Annually |

| Share of electric/e-zero emission equipment | ≥30% | Inventory and operational data from port systems | Semi-annually |

| Share of solar energy in total consumption | ≥70% | Energy monitoring system/smart meters | Quarterly |

| Cargo handling efficiency | +30% compared to 2024 | Throughput analysis based on terminal operations | Quarterly |

| Digitalized processes | 100% | Process mapping and digital workflow audit | Semi-annually |

| Performance Indicator | Target Value by 2030 | Method of Measurement | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total CO2 emissions | 0% (net-zero) | Annual emission inventory report | Annually |

| OPS System coverage | 100% | Monitoring of shore power connections | Quarterly |

| Share of electric/e-zero emission equipment | 100% | Inventory and operational data from port systems | Semi-annually |

| Share of solar energy in total consumption | 100% | Energy monitoring system/smart meters | Quarterly |

| Cargo handling efficiency | +20% compared to 2030 | Throughput analysis based on terminal operations | Quarterly |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Integration | Faster cargo processing, elimination of duplicate data, better control |

| Predictive Analytics | Higher efficiency, fewer delays, reduced operational costs |

| Green Module | ESG alignment, improved reputation, better access to green funding |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lakićević, M.; Niković, A. Navigating Sustainability: The Green Transition of the Port of Bar. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310736

Lakićević M, Niković A. Navigating Sustainability: The Green Transition of the Port of Bar. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310736

Chicago/Turabian StyleLakićević, Milutin, and Aleksandar Niković. 2025. "Navigating Sustainability: The Green Transition of the Port of Bar" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310736

APA StyleLakićević, M., & Niković, A. (2025). Navigating Sustainability: The Green Transition of the Port of Bar. Sustainability, 17(23), 10736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310736