1. Introduction

Currently, numerous countries worldwide have incorporated the development of the electric vehicle industry into their national strategies and successively issued plans for electric vehicle fleet development, covering multiple vehicle categories such as passenger cars and buses, with the aim of further enhancing energy conservation and emission reduction effects in the transportation sector. Incentive policies including financial subsidies, tax reductions and exemptions, and road priority rights have become key means to promote the market penetration of electric vehicles, and their implementation effects and optimization paths have emerged as a research hotspot in the field of sustainable transportation development [

1].

Compared with private electric vehicles, electric buses offer advantages such as fixed operating routes, concentrated charging demands, and controllable operational scenarios, making it easier to develop a standardized promotion model. Additionally, electric buses demonstrate remarkable benefits in energy conservation, emission reduction, and operational cost reduction, thus emerging as a core priority area for the global promotion and application of electric vehicles. According to 2023 statistics, China’s bus fleet reached 682,500 vehicles, of which 554,400 were new energy buses, accounting for a notable 81.2% of the total. The sheer scale of this fleet underscores the immense potential for energy savings and emissions reduction through operational optimization.

Urban signalized intersections represent typical scenarios with interrupted traffic flow, where stochastic signal timing and vehicle dynamics lead to significant energy and operational inefficiencies. Furthermore, the dense distribution of bus stops and their close proximity to intersections, which are common characteristics of urban infrastructure, often disrupt the operational efficiency of bus services [

2]. These disruptions, stemming from traffic signals and passenger boarding/alighting activities, result in repeated acceleration–deceleration cycles, lower average speeds, and degraded powertrain efficiency. Collectively, these factors elevate the energy consumption per unit distance and substantially undermine the overall energy utilization efficiency of electric buses [

3], thereby counteracting their potential environmental benefits.

While various eco-driving strategies have been proposed in existing literature to alleviate energy waste at signalized intersections. Most reported methods are tailored and assessed primarily for intersection-specific scenarios, often sidelining the critical role of upstream and downstream bus stops. Stochastic delays introduced by passenger activities at these stops can fundamentally compromise vehicle trajectory, resulting in intersection-focused optimization strategies being suboptimal or even counterproductive when applied to the segment of bus stop and intersection area. Therefore, there is an urgent requirement for strategies that can holistically orchestrate driving behavior across this coupled system.

This study addresses the critical sustainability challenge of low energy utilization efficiency caused by frequent starts and stops during bus operation. The innovation of this research lies in the development of a novel AI-enhanced eco-driving strategy, uniquely tailored to the complex scenario of the bus stop and intersection road segment. Based on real-world operational data from a typical bus route, this study analyzes the energy consumption characteristics of electric buses under the combined influence of bus stops and intersections. An AI-enhanced eco-driving strategy integrating offline and online Reinforcement Learning (RL) is proposed. Compared with previous studies, the proposed method features two core distinctive advantages: (1) synergistic integration of offline and online RL; (2) coordinated optimization of driving behaviors for both bus stop dwell and traffic signal response within a unified Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) cooperative framework.

As for the structure of this paper,

Section 2 conducts a comprehensive literature review.

Section 3 presents the research framework and data results. The methodology of eco-driving strategy is proposed in

Section 4.

Section 5 conducts the numerical experiments.

Section 6 summarizes the main conclusions and puts forward prospects for future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Energy Consumption Characteristics of Electric Buses

Tang Yi [

4], by constructing a bus energy consumption factor model based on specific power correction, discovered that the bus energy consumption factor exhibits a decreasing power function relationship with speed and is positively correlated with bus mass. The results of their corrected model for calculating average single-trip energy consumption were consistent with the MOVES energy consumption and emissions model, with a calculation error within 12%. Misanovic et al. [

5], based on real-vehicle experimental results from the EKO1 line in Belgrade, found that bus operational factors such as air conditioning system usage and passenger load significantly impact energy consumption per unit distance. Specifically, the use of heating systems during winter could increase energy consumption by approximately 20% to 30%. Kivekäs et al. [

6] established a linear positive correlation between the number of stops and total energy consumption, using the measured data collected on the city Line 11 in Espoo, Finland, Belloni et al. [

7] found that up to 50% of the energy consumed by the motor for traction could be dominated by driving behavior, specifically acceleration patterns and throttle pedal control styles. They noted that aggressive maneuvers like rapid acceleration and frequent deep throttle applications led to high-magnitude energy consumption peaks, whereas gentle maneuvers like gradual starts, constant-speed driving, and the judicious use of coasting distances could effectively reduce the overall energy consumption level. Chen et al. [

8] utilized UAV aerial photography technology to achieve high-precision trajectory extraction (RMSE: 0.175 m), providing a data foundation for analyzing bus operational parameters; Zhuang et al. [

9] adopted a few-shot learning strategy from autonomous driving perception technology, enhancing the recognition capability in special scenarios to optimize energy consumption decisions; Chen et al. [

10] developed a traffic flow prediction denoising model based on wavelet transform, supplying more accurate input data for bus scheduling systems; Li et al. [

11] employed a three-stage predictive control framework (day-ahead electricity purchase optimization, charging power allocation, and real-time energy storage regulation), offering a systematic solution for energy efficiency management of charging infrastructure.

Synthesis of studies [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] indicates that the energy efficiency of electric buses is highly sensitive to operational dynamics, with frequent stops, aggressive driving, and auxiliary loads being primary contributors to energy waste. This understanding directly motivates the development of eco-driving strategies to smooth traffic flow and eliminate inefficient patterns. Integrated solutions incorporating high-precision trajectory monitoring, robust environmental perception, data cleansing, and smart charging management are progressively building a systematic framework for energy optimization. Future research should focus on breakthroughs in multi-source data collaboration and adaptive driving strategy optimization to achieve full-chain energy efficiency improvements.

2.2. Evolution of Eco-Driving Strategies

The research on eco-driving strategies has progressed from model-driven to data-driven approaches. Rule-based and model-based methods provide foundational solutions; for instance, Wu et al. [

12] achieved up to 19.5% fuel consumption reduction through speed optimization at signalized intersections. Long et al. [

13] balanced energy consumption, delay, and comfort under high saturation conditions with a trajectory model, and Xu et al. [

14] planned speed intervals for buses that incorporated operational constraints, significantly improving system economic efficiency. Although intuitive and reliable, the performance of these methods is easily affected by model mismatches in highly stochastic real traffic environments. Optimization-based methods enable explicit multi-objective balancing. Zhu et al. [

15] used Bayesian adaptive optimization to achieve synergistic reductions in energy consumption and emissions, Zhang et al. [

16] demonstrated broad applicability across different driving styles with multi-objective optimization, and Feng et al. [

17] combined model predictive control for real-time optimization, significantly improving energy efficiency and safety while ensuring computational efficiency. However, their effectiveness is constrained by computational complexity and model accuracy. To learn driving behavior patterns from data, supervised learning methods have been widely applied: Zhang et al. [

18,

19] constructed high-precision driving behavior recognition models based on trajectory data to support energy saving interventions; Niu et al. [

20] explored cooperative car-following strategies for connected vehicles, reducing emissions by approximately 15%; Li et al. [

21] proposed segmented speed strategies for different queue scenarios, achieving significant energy savings. However, the policies derived from these methods are often static and difficult to adapt online. Reinforcement learning methods have shown great potential due to their ability to learn optimal policies through interaction with the environment. Lu et al. [

22] simultaneously optimized energy efficiency and safety in mixed traffic flow, while Qin et al. [

23] and Xi et al. [

24] proposed deep reinforcement learning frameworks for conventional vehicles and electric buses, respectively, demonstrating excellent multi-objective synergistic optimization capabilities and robustness in complex intersection scenarios.

Studies [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] indicate that research on eco-driving strategies has shifted from model-driven to data-driven approaches. Early rule-based and model-based methods, while intuitive, are susceptible to model mismatch; optimization methods are constrained by computational complexity; supervised learning generates static policies that are difficult to adapt online. In contrast, reinforcement learning methods achieve dynamic multi-objective collaborative optimization through environmental interaction, demonstrating strong robustness in complex scenarios. However, existing research mostly focuses on isolated intersections, and the sequential decision-making challenge for buses navigating the typical “bus stop–intersection” corridor, particularly reinforcement learning frameworks that integrate offline pre-training and online fine-tuning, remains underexplored.

2.3. Summary of Quantitative Findings from Literature

To provide a clear overview of the performance achievements in the field of eco-driving,

Table 1 synthesizes key quantitative findings from the reviewed literature. This summary highlights the diversity of approaches and their demonstrated effectiveness across different performance metrics, such as energy savings, emissions reduction, and travel efficiency. The data underscores a common trend: significant energy savings are achievable through intelligent driving strategies, yet the application context and specific methodologies vary widely.

Existing studies on electric bus eco-driving have established a systematic understanding of their energy consumption patterns, yet remain predominantly vehicle-centric. While some research has begun to examine how bus stops influence stopping and driving behaviors, there is a notable absence of quantitative energy consumption analysis based on real operational data that jointly considers driving modes within integrated “bus stop–intersection” scenarios. Meanwhile, RL has shown growing potential in traffic control applications due to its capacity for continuous optimization and adaptive decision-making. Specifically, online RL enables dynamic control through real-time environmental interaction, whereas offline RL can train effective models directly from historical datasets, offering distinct advantages in high-risk or high-cost settings. To bridge these gaps, this paper introduces a dual-phase RL framework combining offline pre-training with online fine-tuning, designed to develop an eco-driving strategy for the “bus stop–intersection” scenario that reflects real-world operational characteristics while maintaining adaptability in complex traffic environments.

3. Materials

3.1. Research Framework

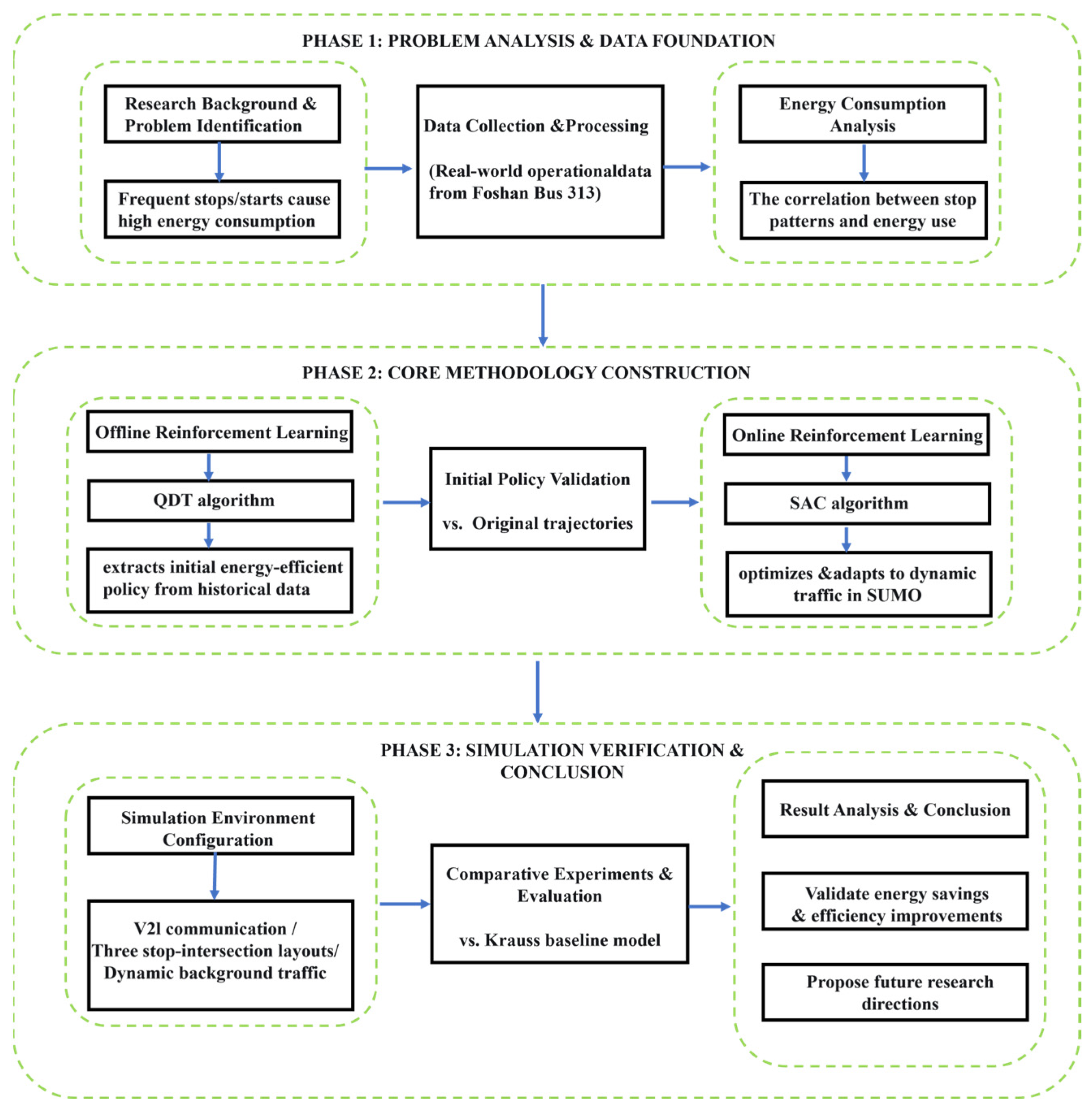

This study develops a three-phase sustainability optimization framework (detailed in

Section 4) specifically designed to enhance the energy efficiency and operational sustainability of electric bus operations in urban environments. The optimization method of eco-driving strategy is shown in

Figure 1.

Phase 1: Data-Driven Analysis of Operational Characteristics.

Leveraging real-world operational data from a specific bus route in China, this study systematically analyzes the overall distribution characteristics of power, speed, and acceleration for electric buses operating under complex environmental conditions, including varying road hierarchy levels, traffic flow states, and load conditions.

It further investigates the impact of frequent stops and starts at bus stops and intersections on overall operational efficiency and energy consumption levels.

The analysis examines the characteristics of variation in energy consumption per unit distance relative to the distance between bus stops and intersections, thereby providing the data foundation and theoretical basis for developing an eco-driving strategy.

Phase 2: Offline RL for Initial Strategy Learning.

Using offline reinforcement learning (RL) methods based on real bus trajectory data, this study extracts “state–action–reward” correlations.

It performs imitation learning of bus behavioral patterns under different states to output an energy saving control strategy that possesses practical deployment potential while aligning closely with real-world data distribution.

This process results in an initial policy exhibiting both stability and practicality.

Phase 3: Online RL for Strategy Optimization and Evaluation.

An online reinforcement learning approach is employed to optimize the pre-trained policy.

A simulation environment reflecting fundamental urban traffic characteristics is designed using the Simulation of Urban MObility (SUMO) platform with the version of 1.25.0.

Experience trajectories are generated based on the initial policy to build a behavioral experience dataset.

This dataset is introduced into the experience replay buffer as initial experience.

The system iteratively generates new experience through ongoing interactions between the bus agent and the simulation environment for RL training, continuously updating the policy parameters in real-time.

This culminates in a robust eco-driving strategy.

A comparative simulation analysis is conducted between this strategy and SUMO’s default Krauss driving model to analyze the operational mechanisms contributing to energy savings.

3.2. Data Collection

This study is grounded in a robust empirical foundation, utilizing real-world operational data from a specific bus route in China for July 2020. The selected route, spanning 15.47 km with 31 stops, traverses a representative variety of urban functional landscapes, including expressways, arterial roads, and secondary arterials. This carefully chosen corridor encapsulates the operational challenges and opportunities within diverse urban settings (e.g., residential, commercial), ensuring the findings are directly relevant for improving the sustainability of urban public transport systems under varying infrastructure and traffic conditions.

To capture a comprehensive picture of operational dynamics, data collection was strategically designed to include both weekdays and weekends, with balanced coverage of morning/evening peak hours and off-peak periods. This temporally diverse data collection strategy is critical for understanding vehicle performance across the full spectrum of real-world service conditions, including different passenger load factors and traffic flow environments. Such comprehensiveness is essential for developing an eco-driving strategy that is both effective and robust, key to achieving consistent energy savings and emissions reductions.

The subject vehicle was equipped with a sophisticated on-board diagnostics (OBD) system, recording high-resolution time series data on critical parameters such as energy consumption, GPS trajectories, speed, gradient, and altitude [

25]. These multimodal datasets provide a holistic view of the vehicle–environment interactions that determine energy efficiency. The key collected metrics, which offer complementary insights into vehicle dynamics and energy use, are systematically detailed in

Table 2.

3.3. Data Processing

3.3.1. Power Calculation

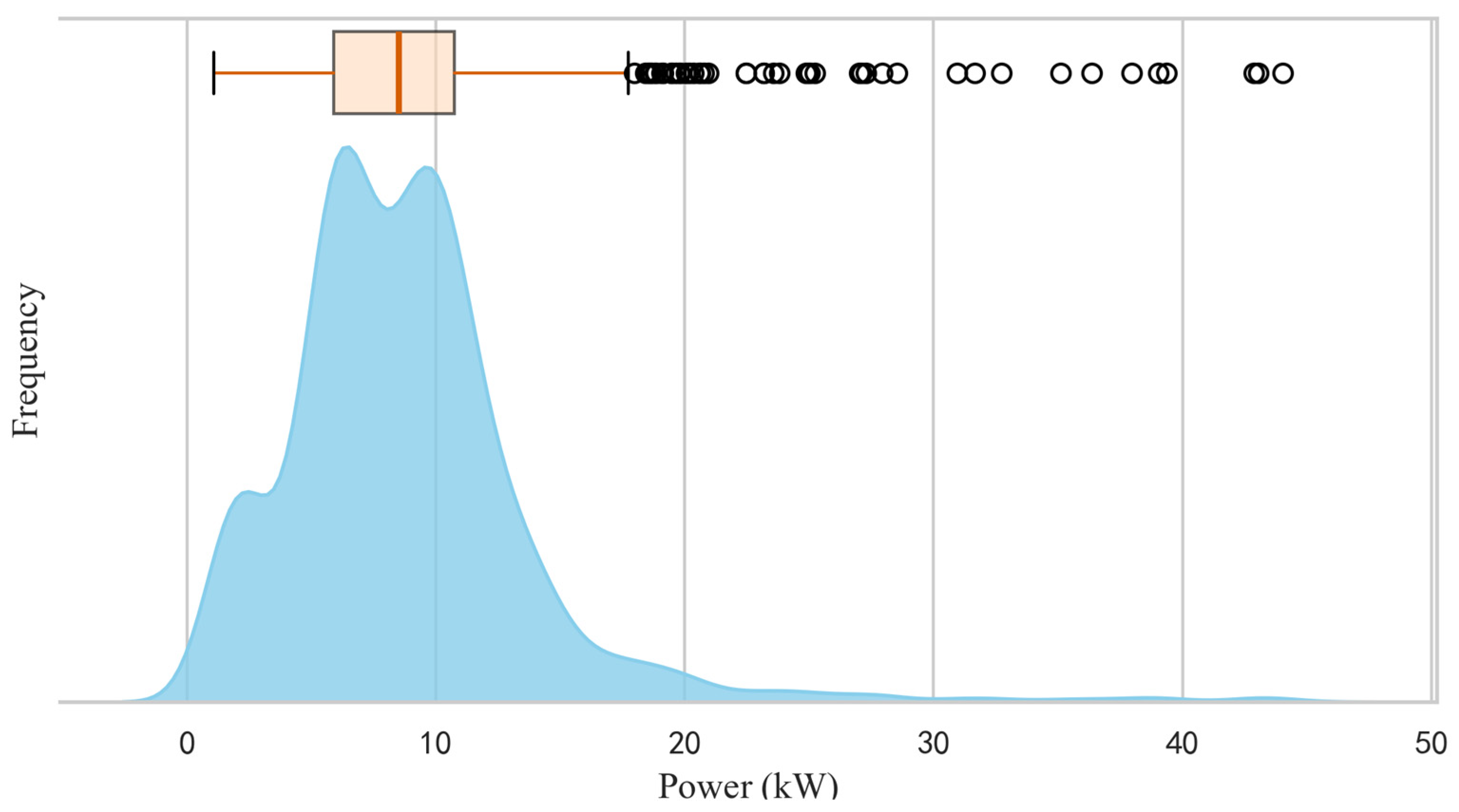

As shown in

Figure 2, the power distribution of the target vehicle during stationary states exhibits specific characteristics. While most power values concentrate around 10 kW (reflecting stable auxiliary load demand), the presence of negative power values indicates limited energy recuperation. Crucially, clearly identifiable high-magnitude outliers are observed, likely caused by transient power surges during system wake-up or pre-charging events.

Given that these outliers differ significantly from steady-state power characteristics and cannot represent typical auxiliary system behavior, we exclude them from subsequent auxiliary power calculations.

The energy decomposition principle governs drive power derivation via Equation (1), where drive power equals total power minus auxiliary power:

where

: Drive power (kW)

: Auxiliary power (kW). The average value of auxiliary power excluding outliers is 8.09 kW.

3.3.2. Acceleration Calculation

Vehicle acceleration is derived through force–power equilibrium according to Equations (2) and (3) balancing power output against systematic resistance forces:

where

: Velocity (m/s)

: Rolling resistance (N)

: Aerodynamic drag (N)

: Grade resistance (N)

: Vehicle curb mass (kg)

: Average passenger mass (kg)

: Passenger count (onboard)

: Gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s2)

: Rolling resistance coefficient (0.008)

: Road gradient angle (rad)

: Aerodynamic drag coefficient (0.6)

: Frontal area (m2)

: Air density (kg/m3)

3.3.3. Energy Consumption Analysis

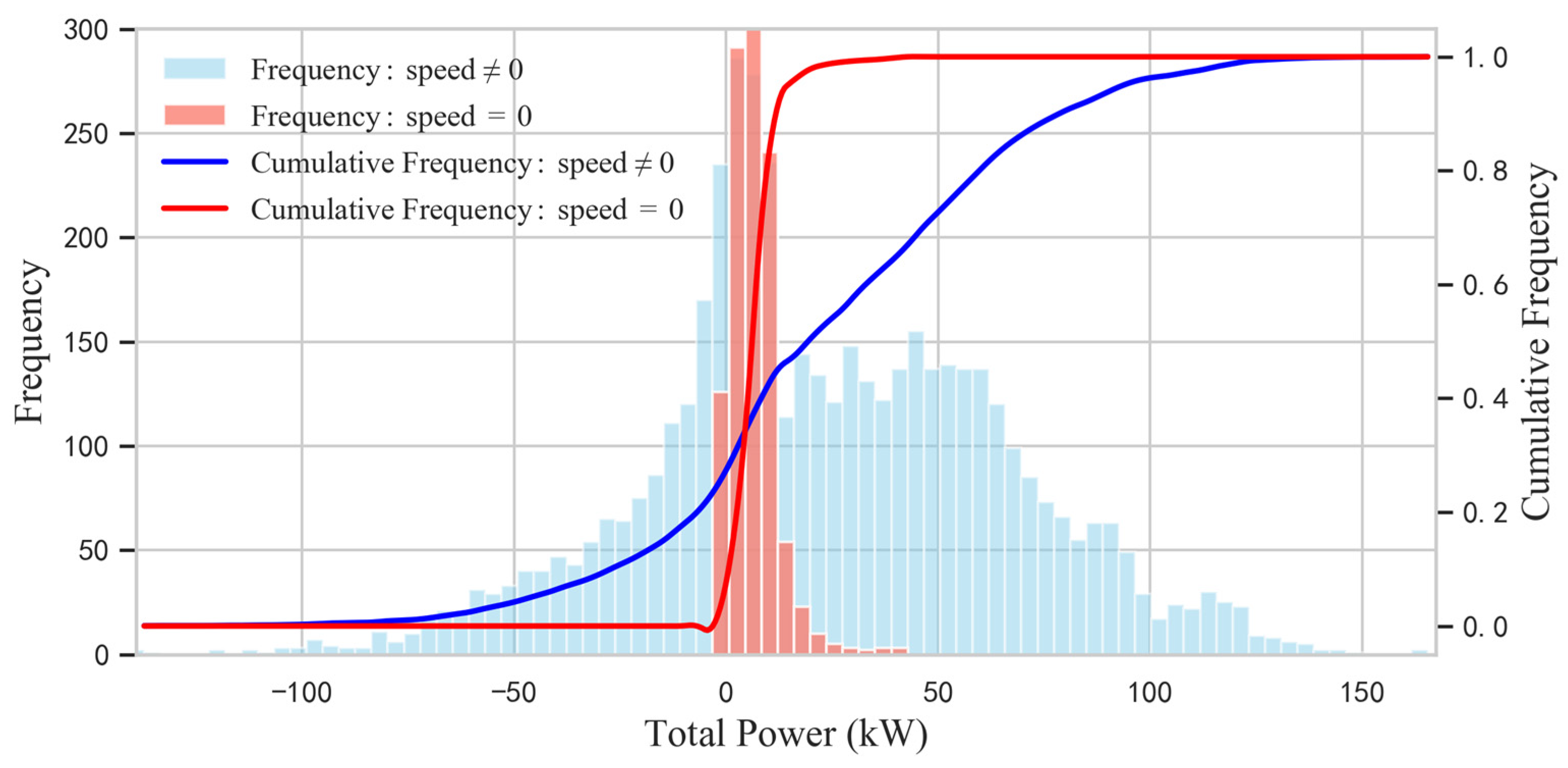

The distribution of total vehicle power (

Figure 3) reveals a fundamental contrast between static and dynamic states.

During stationary operation, power output is concentrated around 10 kW, indicating a consistent baseline auxiliary load. In deceleration phases, negative power values approaching zero confirm low-level energy recuperation capabilities. Notably, the power distribution during motion displays increased dispersion, significantly amplified fluctuations, and high-frequency clustering near 0 kW.

This diverse profile stems from the vehicle’s frequent transitions between acceleration, deceleration, idling, and recuperation cycles, resulting in wide-ranging power oscillations. The marked difference between static stability and dynamic variability directly correlates with the complex driving patterns typical of urban bus operations.

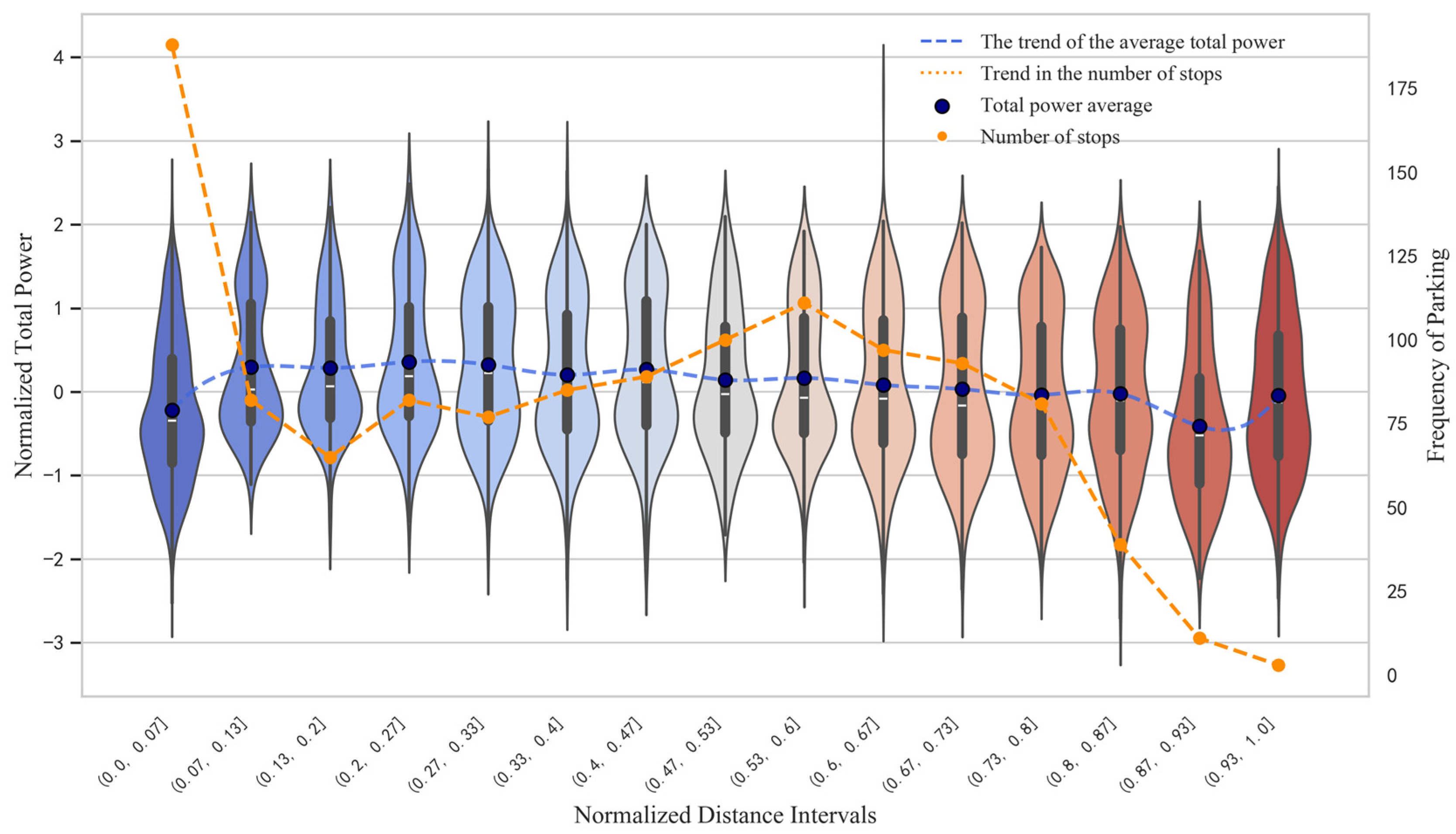

The power and stop distributions between bus stops and intersections, illustrated in

Figure 4, show distinct patterns across operational phases. During bus stop approach, frequent braking and energy recuperation operations generate pronounced negative skewness in the power distribution, creating a contrast to acceleration behavior. Vehicle startup triggers a rapid change, where power levels surge upward, opposing the preceding deceleration phase.

A clear spatial relationship emerges after vehicle startup: power distribution patterns demonstrate an inverse variation relative to stop frequencies across different road segments. Areas with lower stop frequency show highly concentrated power distributions and reduced mean power values, whereas high stop frequency zones exhibit substantially broader dispersion and elevated averages.

This complementary pattern was quantitatively validated through correlation analysis of segments beyond a normalized distance of 0.2. A robust interdependence between mean power and stop counts is confirmed by a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.807 (p < 0.001), signifying a statistically significant co-variation throughout vehicle operation. The combination of localized variations during transient phases and macro-level spatial patterns collectively characterizes the energy dynamics of electric buses in stop–intersection corridors.

The unit-distance energy consumption between stops and intersections is calculated according to Equation (4).

where

: Energy consumption per unit distance (kWh/km)

: Distance between stop and intersection (km)

: Entry time to stop zone (s)

: Arrival time at intersection (s)

4. Methods

4.1. Offline Pre-Training with Q-Learning Decision Transformer

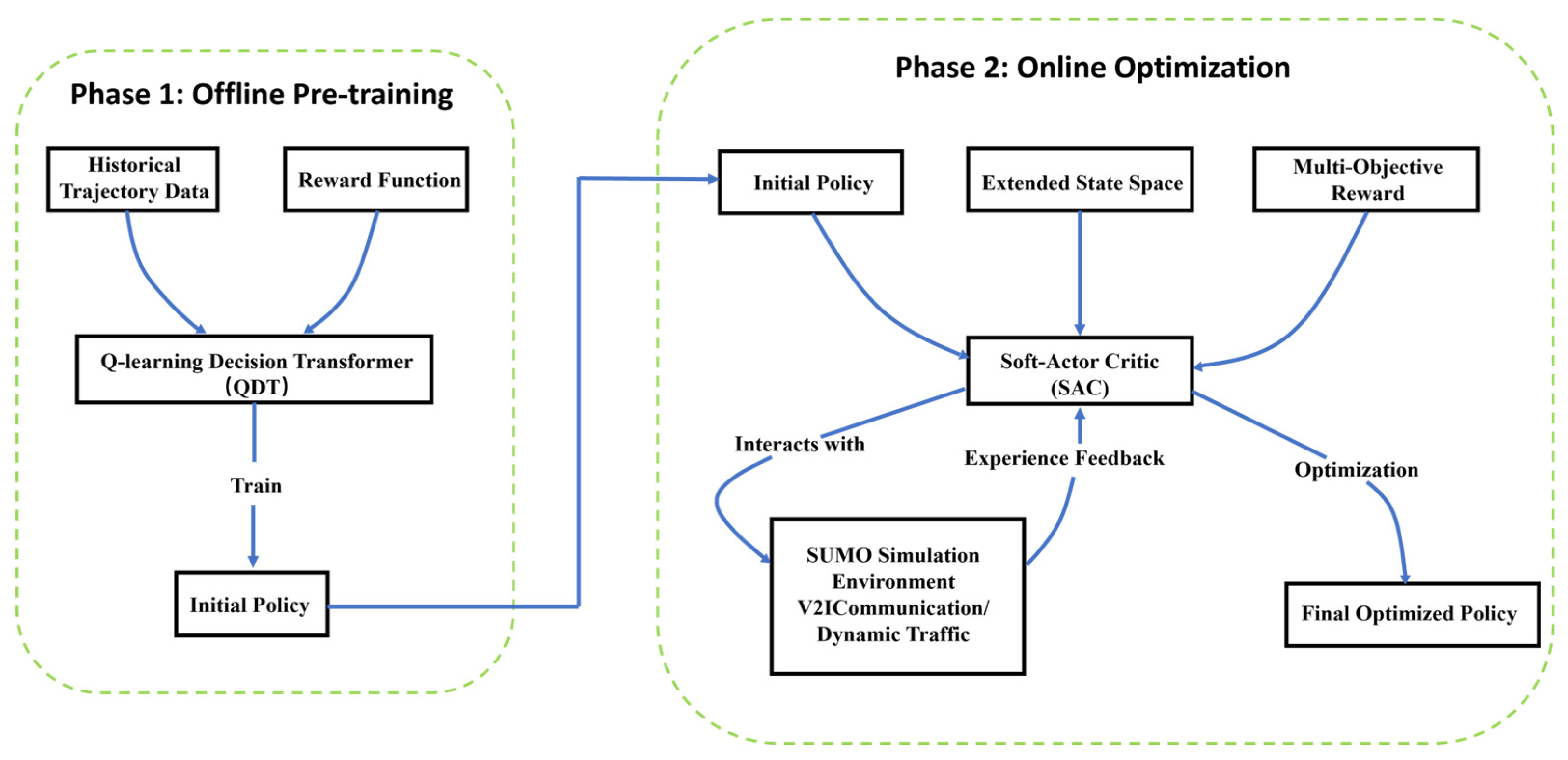

This study develops a three-phase sustainability optimization framework specifically designed to enhance the energy efficiency and operational sustainability of electric bus operations in urban environments. The framework comprises: (1) data-driven operational analysis, (2) offline reinforcement learning for initial strategy acquisition, and (3) online reinforcement learning for policy optimization. In alignment with this framework, the methodology encompasses both offline pre-training from historical data and online fine-tuning in simulated environments. It includes a flow chart of the two-phase deep learning algorithm, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

To acquire a stable and energy-efficient initial policy without the cost and risk of online interaction, we first employed Offline Reinforcement Learning (Offline RL). This approach learns directly from the collected historical trajectory data, imitating and optimizing the driving behaviors embedded in the real-world dataset.

We adopted the Q-learning Decision Transformer (QDT) algorithm for the offline pre-training. QDT synergizes the sequence modeling prowess of the Transformer architecture with the value function foundation of Q-learning. This hybrid design addresses the limitations of prior offline RL methods: it mitigates the extrapolation error common in traditional Q-learning in offline settings, while overcoming the suboptimal trajectory stitching issue of vanilla Decision Transformers by leveraging Q-value estimates to relabel the Return-to-Go (RTG) sequences. This makes it particularly suitable for learning competent policies from our mixed-quality historical driving data.

4.1.1. Reward-Driven Policy Design

The offline RL model was constructed with the following components:

State Space: A 4-dimensional vector encompassing: the current vehicle speed (km/h), the road gradient (rad), the number of onboard passengers (persons), and the instantaneous distance to the upcoming intersection (m).

Action Space: A 1-dimensional continuous variable representing the vehicle’s acceleration, bounded within .

Reward Function according to Equation (5): A multi-objective reward function was designed to incentivize energy efficiency, efficiency, and comfort:

is the instantaneous power (kW), is the speed (km/h), is the acceleration (m/s2), and is a sparse terminal reward granted upon successfully reaching the intersection. The weights of , , were tuned to balance these competing objectives.

4.1.2. Performance of the Initial Offline Policy

The QDT model was trained on a dataset comprising over 31,000 real-world trajectory segments. The performance of the resulting initial policy was rigorously evaluated by comparing its generated trajectories against the original human-driven trajectories, with key metrics summarized in

Table 3.

The offline-learned initial policy demonstrated significant improvements across multiple dimensions, as quantified in

Table 3.

Travel Efficiency: The average speed increased from 21.0 km/h to 31.0 km/h, indicating a substantial improvement in operational fluidity.

Driving Smoothness: The average acceleration shifted markedly from −0.996 m/s2 to −0.231 m/s2. This positive change, with a reduction in the magnitude of negative acceleration, signifies a decisive shift away from harsh braking patterns towards smoother driving.

Energy Consumption Profile: While the instantaneous average power increased—consistent with achieving higher speeds—the crucial metric of cumulative energy consumption decreased by 0.034 kWh per segment. This confirms that the policy successfully converts higher power expenditure into more efficient overall energy use by minimizing wasteful stop–start cycles.

These results validate that the offline RL phase successfully extracted a stable, smoother, and more energy-efficient initial policy from the historical dataset. The policy provides a high-quality and safer starting point for subsequent online optimization, effectively mitigating the cold-start problem.

4.2. Online Reinforcement Learning with Soft Actor-Critic

The SAC (Soft Actor-Critic) algorithm synthesizes the strengths of Actor-Critic methodologies with an entropy-regulated strategy. It maximizes expected returns while incorporating an entropy regularization term, thereby effectively encouraging exploration of state-action spaces and mitigating policy convergence to local optima [

21]. Furthermore, its inherent dual focus on performance and adaptability is reinforced by an adaptive entropy temperature coefficient, which dynamically modulates policy stochasticity to maintain an optimal balance between exploration and exploitation [

22].

The SAC algorithm was chosen as the primary optimization approach due to its unique entropy regularization mechanism, which effectively manages the exploration–exploitation trade-off. This makes it particularly suitable for high-dimensional state spaces (13-dimensional) and multi-objective reward scenarios. Key advantages include:

Entropy term encourages policy exploration, preventing convergence to local optima (e.g., mitigating premature convergence issues common in PPO);

Superior stochastic environment handling compared to TD3 (e.g., adapting to traffic signal phase transitions) through dynamically adjusted randomness via an adaptive temperature coefficient;

Pre-experimental validation: Comparative tests of SAC, PPO, and TD3 demonstrated SAC’s outperformance in both cumulative reward (+10–15%) and convergence speed. The revised version will include brief comparative results and selection rationale.

4.2.1. Physical State Representation

We construct a systematically designed state space that integrates critical operational metrics, traffic context, and mission progress indicators observable in real-road environments [

23]. This framework incorporates thirteen carefully selected features across three categories, as detailed in

Table 4, ensuring comprehensive characterization of kinematic dynamics, contextual constraints, and progression milestones.

4.2.2. Reward Function

The reward function retains its tri-objective architecture across energy efficiency, travel efficiency, and comfort dimensions:

Energy Dimension: Imposes a direct penalty based on instantaneous power consumption during operation.

Efficiency Dimension: Calculated as the ratio of current speed to ideal target speed. Provides positive incentives for higher speeds, balancing energy conservation with travel time requirements.

Comfort Dimension: Employs an acceleration-squared penalty term to constrain abrupt speed changes (mirroring the offline learning setup). Counters kinetic energy fluctuations to ensure passenger comfort.

The unified reward function maintains dimensional equilibrium through Equations (6) and (7).

where

, , : Weight coefficients governing the contribution balance among energy consumption, efficiency, and comfort within the total reward. These weights maintain dimensional equilibrium across objectives by ensuring mathematically commensurate scaling. The weights , , and were determined through grid search optimization to balance the competing objectives of energy efficiency, operational efficiency, and ride comfort.

: Target cruise speed = 10 m/s, representing the kinematic equilibrium point for efficiency optimization.

: Dynamic energy coefficient exhibiting, with value of 1.0 during acceleration (energy consumption)m with the value of 0.25 during deceleration (mirroring energy recuperation at 25% efficiency).

m is the mass of the bus.

: Stationary base power = Random value within [5, 10] kW.

: Simulation timestep (s), serving as the temporal constant for discrete-time reward integration.

4.2.3. Model Parameters

The SAC model parameters, detailed in

Table 5, adopt a structurally framework across policy and value networks:

Both networks utilize stacked fully connected layers with 256 hidden units each,

Activation: ReLU functions ensure nonlinear feature extraction uniformity,

Output: Acceleration commands undergo tanh-constrained compression, mapping outputs to the balanced interval [−3, 3] m/s2. This bounded action guarantees both kinematic feasibility and control stability for longitudinal vehicle dynamics while maintaining algorithmic equilibrium.

The complete training procedure comprised 150 steps, with a batch size of 128 and a replay buffer capacity of 100,000 to ensure stable policy convergence. Training was executed on an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, requiring approximately 2 h of computation time.

5. Simulation Analysis

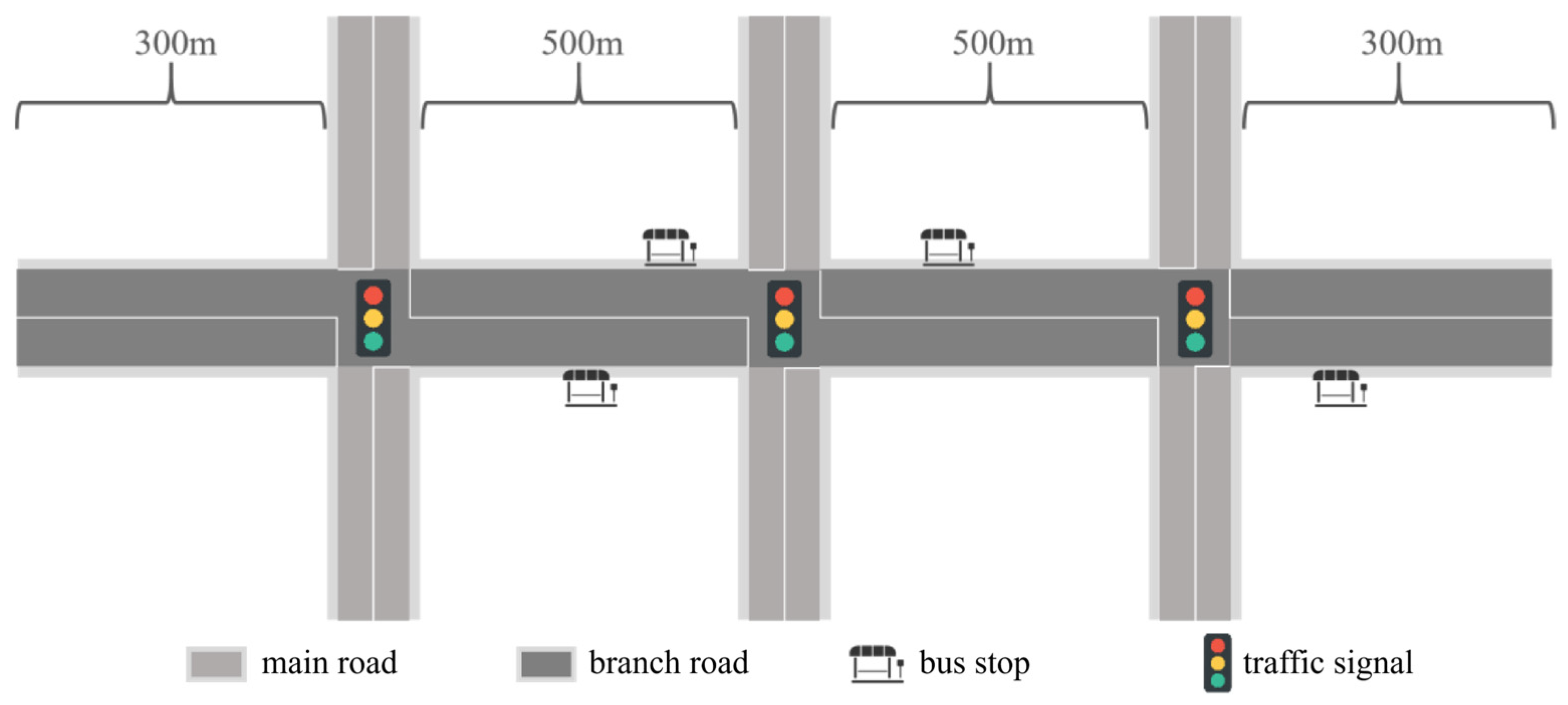

Experimental Design and Evaluation Framework: A comprehensive evaluation of the SAC-optimized eco-driving strategy was conducted by comparing its performance against SUMO’s default Krauss model. The simulation environment, configured according to the parameters in

Figure 6 and

Table 6, enabled a rigorous comparative analysis focused on trajectory characteristics and cumulative energy consumption. To maintain methodological consistency, all performance metrics were evaluated using dimensionally comparable criteria across both models.

Road Network Optimization for Efficient Simulation: To enhance computational efficiency while preserving critical geometric properties, we developed a scaled-down roadway model reducing the total length from 15.47 km to 1547 m. This scaling approach maintained essential topological features—including gradient characteristics at intersections (with a preservation rate of 2.1 ± 0.3%) and curvature profiles—through a validated geometric scaling methodology.

Baseline Model Specification: The Krauss car-following model, originally developed by Stefan Krauss (1997) [

24], establishes collision-free vehicle movement through dynamic speed constraints. The model continuously calculates safe speed thresholds based on surrounding traffic conditions, creating a balanced equilibrium between safety requirements and velocity maintenance.

Road Network Configuration: The simulated road network featured a main road with bidirectional six-lane design and branch roads with bidirectional four-lane access. This configuration ensured consistent maneuverability for buses in both directions, creating a representative environment for strategy learning and validation.

Scenario Coverage for Comprehensive Testing: To address diverse real-world operating conditions, we implemented three distinct station–intersection layouts with varying spatial arrangements:

There is a station upstream of the intersection;

There is a station downstream of the intersection;

There are stations both upstream and downstream of the intersection.

The probability of successful signal transmission decays monotonically with increasing vehicle-to-intersection distance. Drawing upon the theoretical foundations of the Log-Distance Path Loss Model and Log-Normal Shadow Fading Model, we specifically employ a centrally Sigmoid function for modeling [

25]. The signal loss probability function exhibits inverse distance as defined by Equations (8) and (9).

where

: Inflection point = 800 m, representing the spatial axis where communication transitions from stable to unstable states.

: Slope control coefficient, calibrated to achieve complementary boundary.

All performance metrics (e.g., energy savings, time reduction) will be reported with 95% confidence intervals and standard errors based on 10 independent simulation runs. Paired t-tests were conducted to compare SAC against the Krauss model (, significance level ), with results (p < 0.001) demonstrating the statistical significance of the optimized strategy’s superiority.

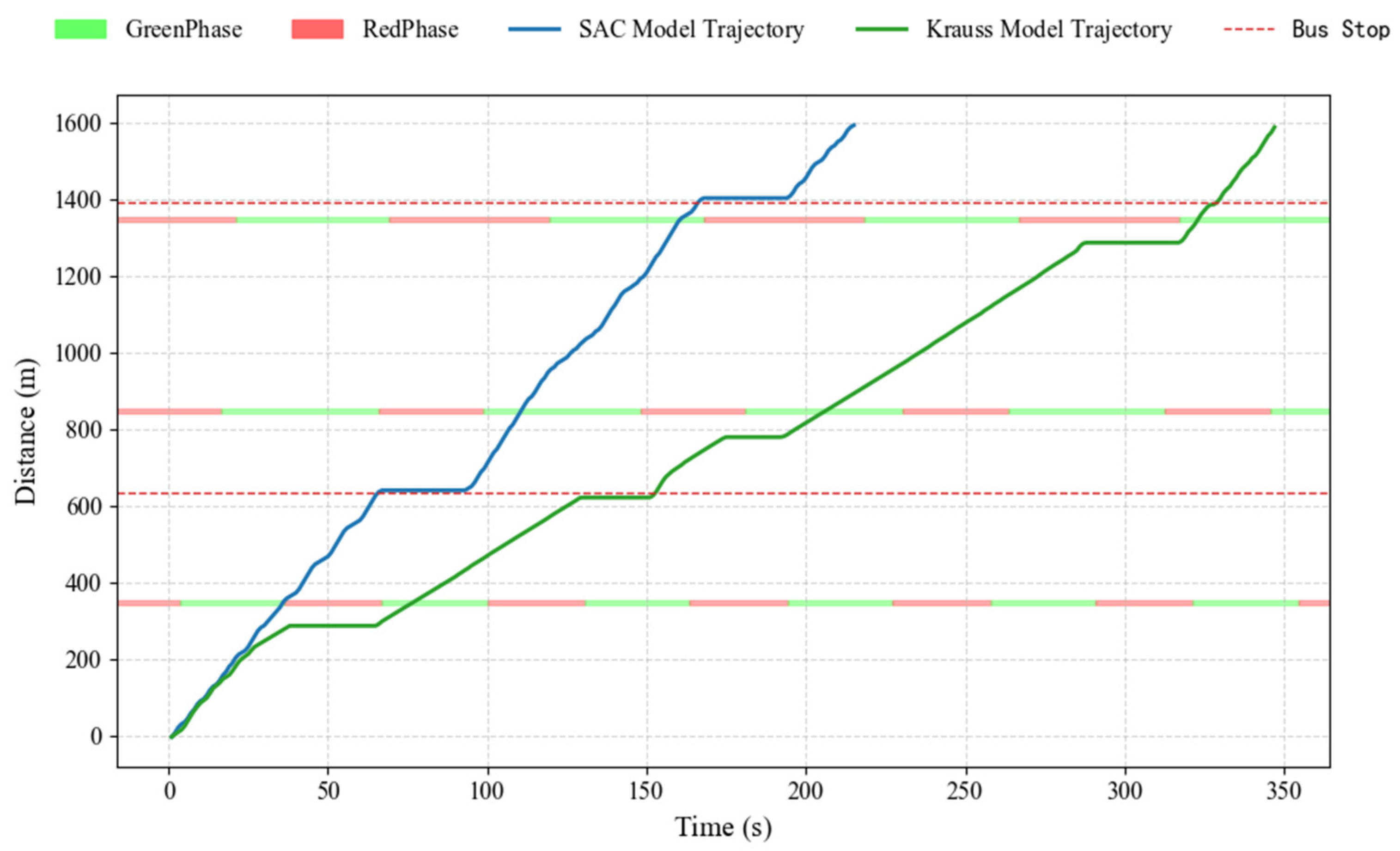

The trajectory comparison is shown in

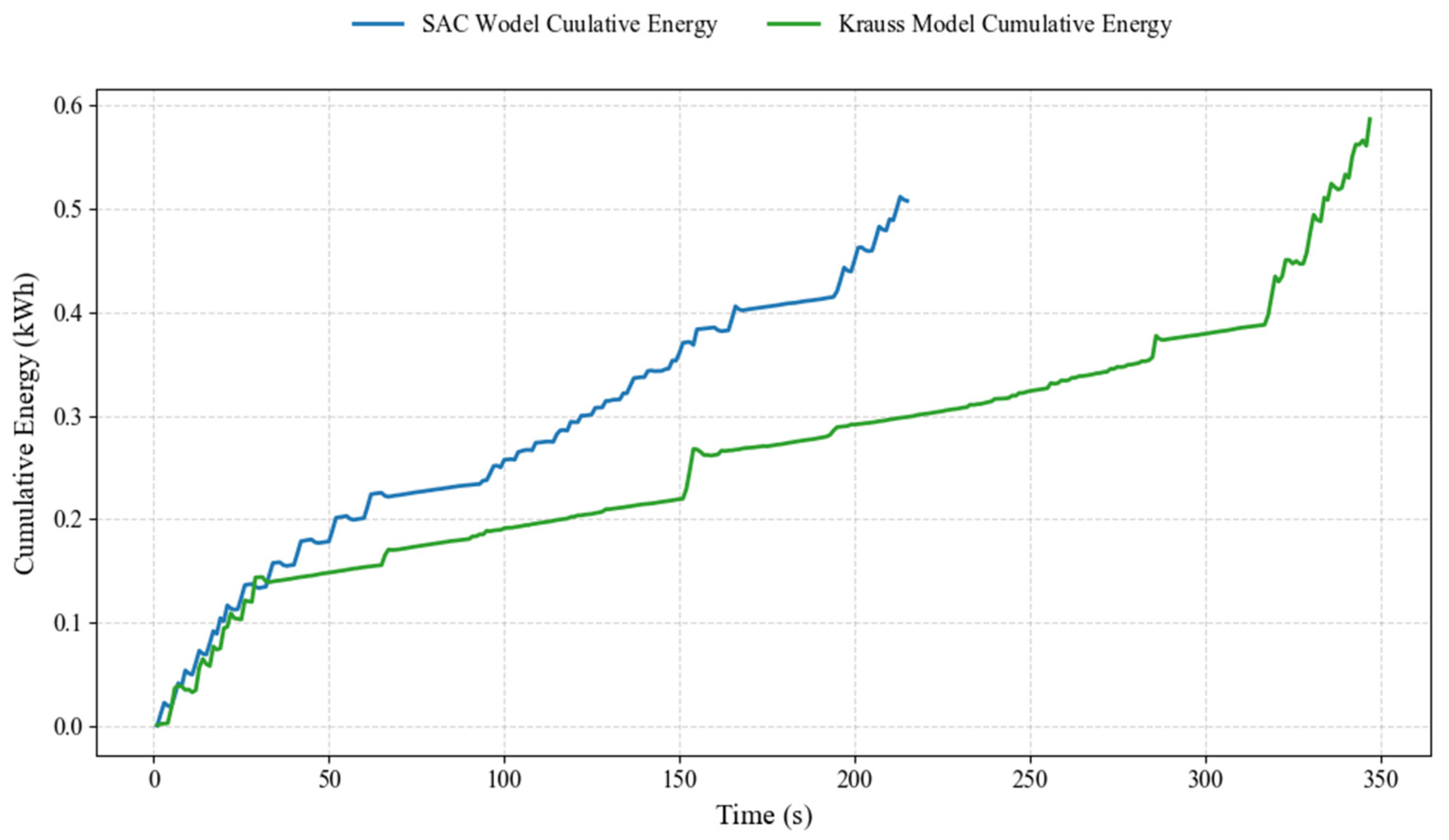

Figure 7. The comparison of cumulative energy consumption is shown in

Figure 8.

Based on simulation data, the Krauss model achieved an average travel time of 346.6 s (mean of 10 simulation runs) over the identical 1547 m route, while the SAC model reduced this to 216.1 s. This corresponds to an absolute reduction of 130.5 s (346.6–216.1) and a relative reduction of (130.5/346.6) × 100% ≈ 37.7%.

Similarly for energy consumption, the Krauss model yielded an average cumulative energy consumption of 0.587 kWh, whereas the SAC model consumed 0.521 kWh. The absolute energy savings amounted to 0.066 kWh (0.587–0.521), equating to a relative reduction of (0.066/0.587) × 100% ≈ 11.2%.

6. Conclusions

This study focuses on the operational segments of electric buses in integrated “bus stop–intersection” scenarios. Using real-world operational data, it systematically analyzes the impact of stop–start behavior on functional energy consumption and proposes an eco-driving strategy framework that integrates offline trajectory learning with online reinforcement optimization. By dynamically adjusting acceleration parameters to optimize vehicle operating states, the framework enhances energy efficiency, with its performance validated through comparative experiments and simulation.

Results demonstrate that stopping frequency in “bus stop–intersection” segments significantly influences the electric buses’ energy consumption per unit distance. Compared to the original trajectories, trajectories optimized by the ODT model increase average speed from 21 km/h to 31 km/h, markedly reduce fluctuations in average acceleration, and lower energy consumption per unit distance from 0.219 kWh to 0.185 kWh. In contrast to the Krauss driving model, the SAC model with integrated online strategy optimization reduces total travel time by 126.78 s and decreases cumulative trajectory energy consumption by 0.073 kWh.

While the proposed two-stage deep reinforcement learning framework demonstrates promising results for eco-driving of electric buses, several limitations remain, pointing to valuable directions for future research. First, there exists a gap between offline and online state representations: the offline pre-training employs a simplified state space, whereas the online simulation operates in a high-dimensional environment. This dimensional mismatch complicates the policy transfer and experience replay buffering process, potentially compromising policy stability during the fine-tuning phase. Second, the simulation network is structurally simplified and does not account for the complexities of a city-scale road network. Additionally, the strategy is trained from a single-agent perspective, neglecting potential interactions among multiple buses operating concurrently. Furthermore, the current strategy exhibits limited robustness to unplanned events, lacking explicit mechanisms to handle incidents such as accidents or severe congestion. To address these limitations, future research should focus on the following directions:

Develop a unified training framework that seamlessly integrates offline historical data with online interaction, algorithmically reconciling state representation differences to enable more stable and efficient policy initialization and fine-tuning.

Extend the simulation environment to city-scale road networks and introduce multi-agent reinforcement learning to train cooperative eco-driving strategies for multiple buses, achieving system-wide optimization of traffic flow and energy efficiency.

Enhance policy robustness through adversarial training, incorporating a wider range of stochastic disturbances and edge-case scenarios during training, and explore techniques such as control barrier functions to build dynamic emergency response capabilities.

Moreover, to improve the generalizability and practicality of the strategy, future work should expand the research to multi-powertrain systems (e.g., fuel cell and hybrid buses), investigate cross-vehicle policy transfer frameworks based on meta-reinforcement learning, and incorporate more complex road structures (e.g., interchanges, tidal lanes) into simulations, thereby promoting the application of eco-driving strategies in broader and more realistic traffic scenarios.