Enhancing Sustainable Intelligent Transportation Systems Through Lightweight Monocular Depth Estimation Based on Volume Density

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel capacity redistribution strategy that achieves a lightweight NeRF architecture.

- We introduce a CMUNeXt module utilizing large-kernel depth separable convolutions and inverted bottleneck design, for robust scene understanding in autonomous driving scenarios.

- We develop an adaptive sampling strategy using one-dimensional Gaussian mixture models, effectively reducing long-distance ray sample numbers while preserving geometric accuracy in large-scale scenes.

- We propose a comprehensive multi-component loss function with specialized handling of occluded regions, achieving significant improvements in depth estimation quality for challenging areas where traditional methods typically fail.

- We conduct extensive experiments on both KITTI and V2X-Sim datasets, demonstrating superior performance in occlusion handling and long-range depth estimation while maintaining real-time deployment capabilities suitable for edge computing devices.

2. Related Work

2.1. Supervised Learning-Based Monocular Depth Estimation

2.2. Self-Supervised Learning-Based Monocular Depth Estimation

2.3. NeRF-Based Monocular Depth Estimation Methods

3. Method

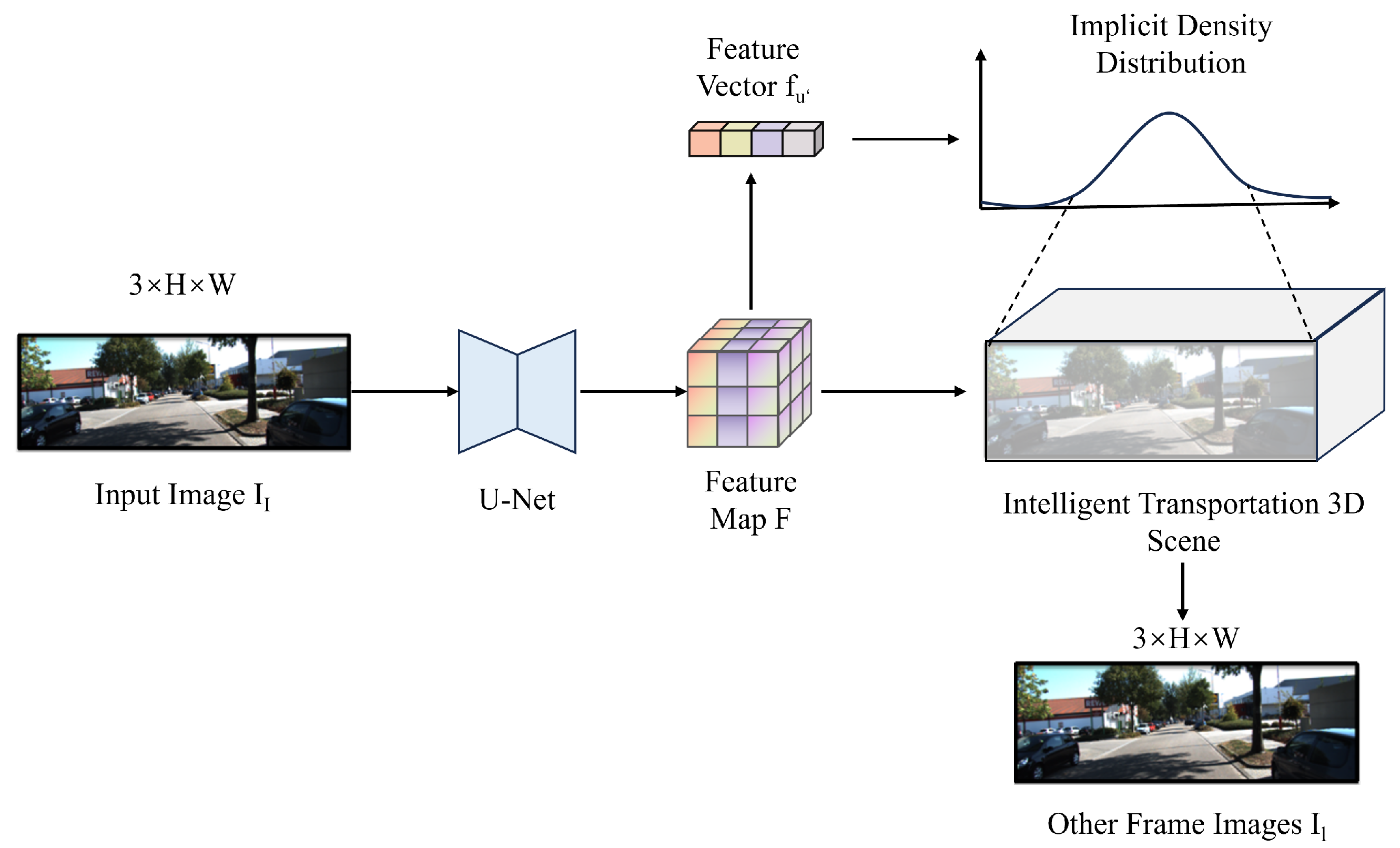

3.1. Framework Overview

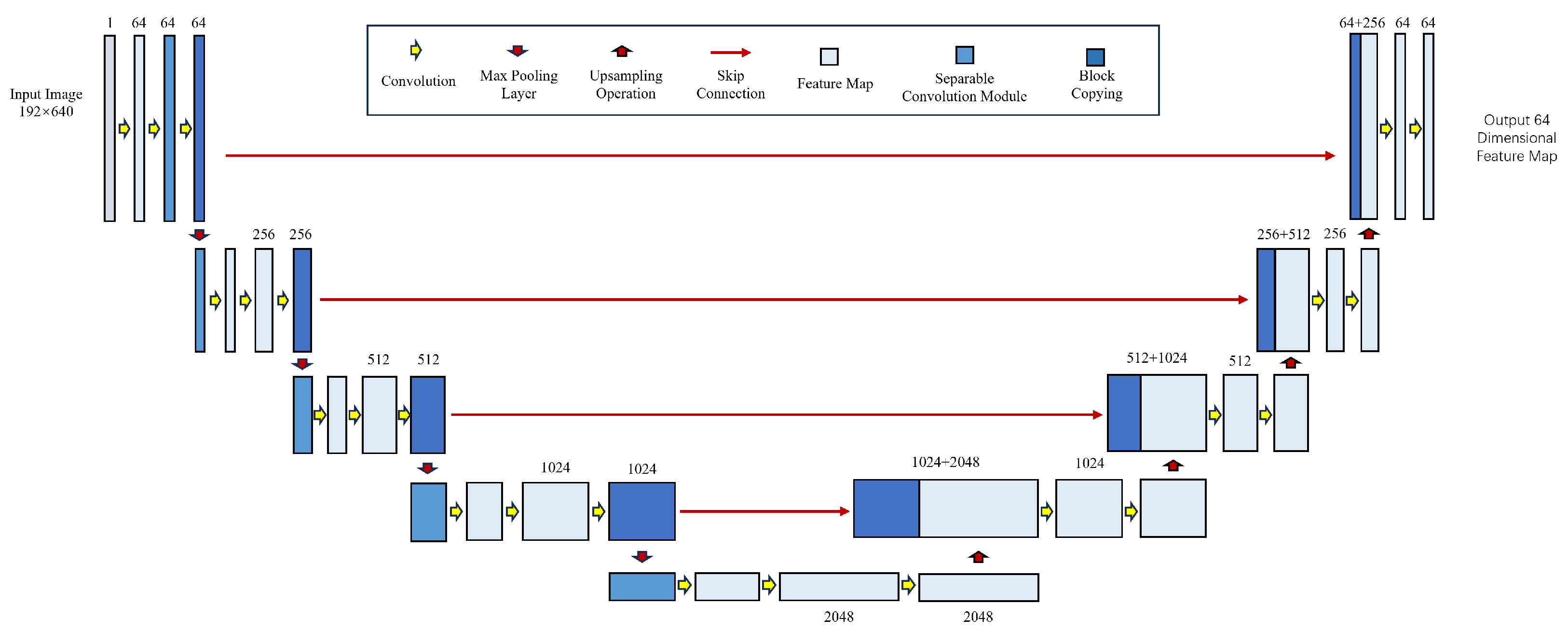

3.2. Separable Convolution-Based Encoder–Decoder Network

3.2.1. Architecture Design Principles

3.2.2. Encoder Architecture and Design

3.2.3. Multi-Scale Feature Integration

3.2.4. Global Context Information Extraction

Motivation and Design Rationale

CMUNeXt Module Architecture

Technical Implementation and Advantages

3.3. Lightweight NeRF-Based Volume Density Prediction

3.3.1. Feature-Conditioned Density Estimation

3.3.2. Adaptive Sampling Strategy

3.3.3. Gaussian Sampling Model Theory

Mathematical Formulation

Bayesian Interpretation

Theoretical Advantages

- Convergence Guarantees: The use of importance sampling with Gaussian proposals ensures faster convergence of the volume rendering integral estimation, as samples are concentrated in regions with non-negligible contributions to the final result.

- Uncertainty Quantification: The variance parameters naturally encode the uncertainty in depth predictions, allowing adaptive sampling density based on prediction confidence.

- Multi-modal Representation: The mixture model formulation enables representation of multiple potential surface locations along a single ray, which is particularly beneficial in semi-transparent or reflective regions.

Connection to Volume Rendering

3.3.4. Volume Density Prediction Network

3.3.5. Volume Rendering and Depth Integration

3.4. Training Strategy and Loss Functions

3.4.1. Comprehensive Loss Function Design

Depth Reconstruction Loss

Smoothness Regularization

Surface Normal Consistency

3.4.2. Occlusion-Aware Training Strategy

Occlusion Detection and Segmentation

Adaptive Loss Weighting for Occluded Regions

3.5. Sustainability Quantification Framework

3.5.1. Computational Sustainability Metrics

3.5.2. Deployment Sustainability Analysis

- Training Phase Sustainability: Reduced computational requirements during model development and fine-tuning

- Inference Phase Efficiency: Lower power consumption during real-time operation on edge devices

- Hardware Longevity: Extended hardware lifespan due to reduced thermal stress from lower computational loads

- Scalability Benefits: Efficient scaling to large vehicle fleets with minimal additional energy costs

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset Description

4.1.2. Implementation Details

4.1.3. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

4.1.4. Training Strategy

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

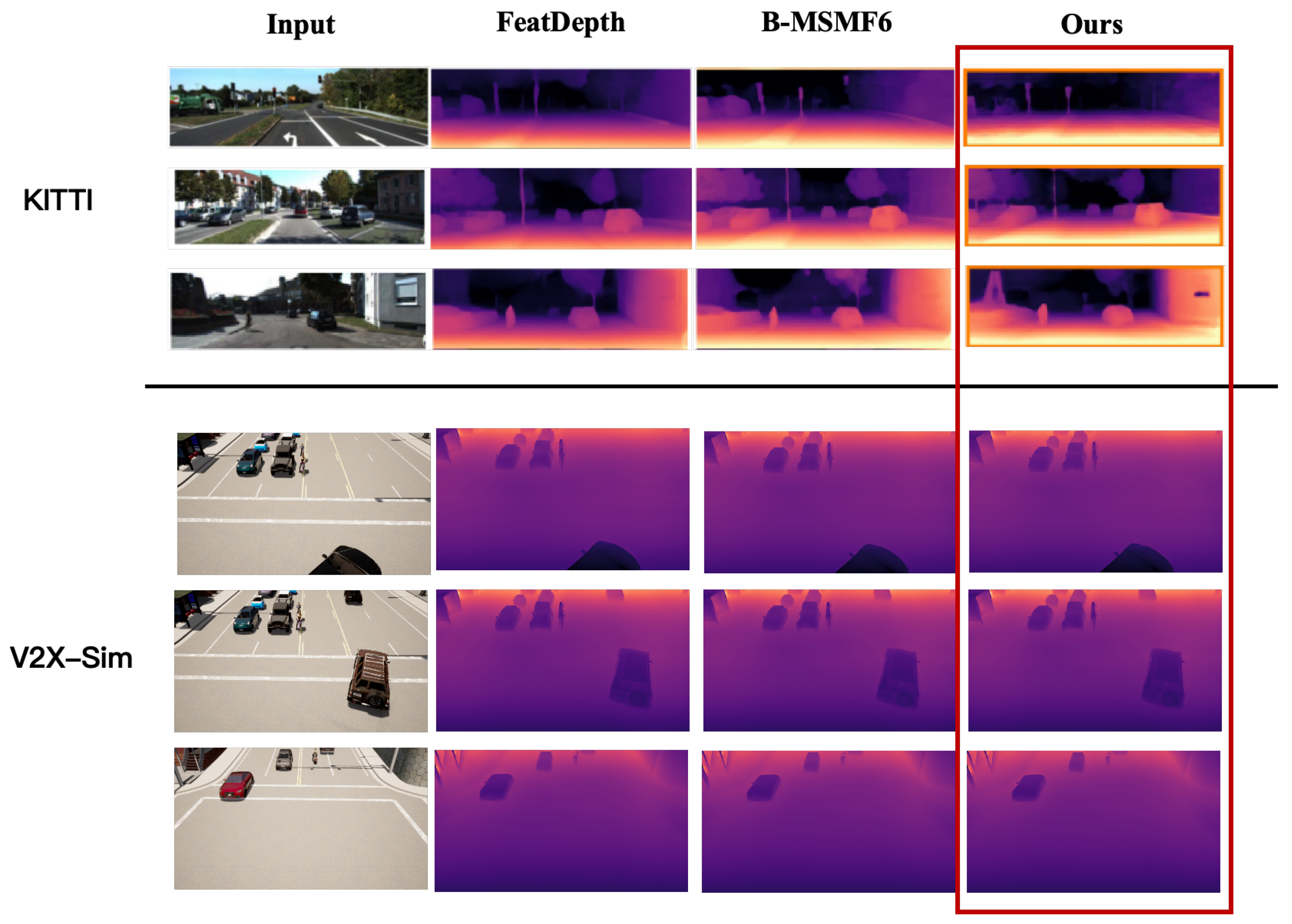

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.4. Ablation Studies

4.4.1. Component Analysis

4.4.2. Reprojection Loss Validation

4.4.3. Probabilistic Ray Sampling Analysis

4.4.4. Lightweight NeRF Architecture Validation

4.4.5. Ray Discarding Strategy Analysis

4.5. Sustainability Performance Evaluation

4.5.1. Energy Consumption Analysis

4.5.2. Environmental Impact Assessment

- Annual Carbon Reduction: 12.7 kgCO2 per vehicle compared to VisionNeRF baseline

- Total Fleet Impact: Approximately 12.7 tons CO2 reduction annually for a 1000-vehi-cle fleet

- Energy Efficiency: 83% higher Energy Efficiency Ratio compared to FeatDepth

- Hardware Requirements: Enables deployment on lower-power edge devices, further reducing energy consumption

4.6. Qualitative Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Sustainability Implications

5.2. Practical Utility and Industrial Applications

5.3. Scientific Contributions and Research Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NeRF | Neural Radiance Field |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| KITTI | Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Toyota Technological Institute |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

References

- Jiang, H.; Ren, Y.; Fang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Yu, H. SHIP: A state-aware hybrid incentive program for urban crowd sensing with for-hire vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 3041–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, D.; Wu, Y.; Du, W.; Yang, C.; Jin, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, F. Smart Prediction-Planning Algorithm for Connected and Autonomous Vehicle Based on Social Value Orientation. J. Intell. Connect. Veh. 2025, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yu, H. Toward city-scale vehicular crowd sensing: A decentralized framework for online participant recruitment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 17800–17813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Ren, Y.; Yu, H. MLF3D: Multi-Level Fusion for Multi-Modal 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 2–5 June 2024; pp. 1588–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, K.; Gao, Y.; He, H.; Lu, D.; Xu, L.; Li, J. Nerf: Neural radiance field in 3d vision, a comprehensive review. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.00379. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Sima, C.; Dai, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, L.; Wang, H.; Zeng, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Deng, H.; et al. Delving into the devils of bird’s-eye-view perception: A review, evaluation and recipe. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 2151–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoumian, A.; Rashwan, H.A.; Cristiano, J.; Asif, M.S.; Puig, D. Monocular depth estimation using deep learning: A review. Sensors 2022, 22, 5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Yin, R.; Jung, S.; Park, S.-I.; Yoo, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J. Mapdistill: Boosting efficient camera-based hd map construction via camera-lidar fusion model distillation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 166–183. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli, L.; Sakaridis, C.; Yu, F. idisc: Internal discretization for monocular depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 21477–21487. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Nex, F.; Vosselman, G.; Kerle, N. Lite-mono: A lightweight cnn and transformer architecture for self-supervised monocular depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 18537–18546. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, B.; Obukhov, A.; Huang, S.; Metzger, N.; Daudt, R.C.; Schindler, K. Repurposing diffusion-based image generators for monocular depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 9492–9502. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli, L.; Yang, Y.H.; Sakaridis, C.; Segu, M.; Li, S.; Van Gool, L.; Yu, F. UniDepth: Universal monocular metric depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 10106–10116. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S.F.; Birkl, R.; Wofk, D.; Wonka, P.; Müller, M. Zoedepth: Zero-shot transfer by combining relative and metric depth. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.12288. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J.; Firman, M.; Brostow, G.J.; Turmukhambetov, D. Self-Supervised Monocular Depth Hints. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2162–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei, L.; Mannocci, E.; Tosi, F.; Poggi, M.; Mattoccia, S. Depth AnyEvent: A Cross-Modal Distillation Paradigm for Event-Based Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–25 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Shan, H.; Jiang, H.; Xiao, J.; Chang, Y.; He, Y.; Yu, H.; Ren, Y. E-MLP: Effortless Online HD Map Construction with Linear Priors. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 2–5 June 2024; pp. 1008–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, R.; Kumar, B.V.; Carneiro, G.; Reid, I.D. Unsupervised CNN for Single View Depth Estimation: Geometry to the Rescue. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, C.; Mac Aodha, O.; Brostow, G.J. Unsupervised Monocular Depth Estimation with Left-Right Consistency. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2016; pp. 6602–6611. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Girshick, R.B.; Farhadi, A. Deep3D: Fully Automatic 2D-to-3D Video Conversion with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, H.; Li, R.; Jiang, H.; Fan, Y.; Li, B.; Hao, X.; Zhao, H.; Cui, Z.; Ren, Y.; Yu, H. Stability Under Scrutiny: Benchmarking Representation Paradigms for Online HD Mapping. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Hong, B.; Soatto, S. Bilateral Cyclic Constraint and Adaptive Regularization for Unsupervised Monocular Depth Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 5637–5646. [Google Scholar]

- Andraghetti, L.; Myriokefalitakis, P.; Dovesi, P.L.; Luque, B.; Poggi, M.; Pieropan, A.; Mattoccia, S. Enhancing Self-Supervised Monocular Depth Estimation with Traditional Visual Odometry. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Québec City, QC, Canada, 16–19 September 2019; pp. 424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wan, J.; He, Z.; Song, J.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, D. Sparse agent transformer for unified voxel and image feature extraction and fusion. Inf. Fusion 2024, 110, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Poggi, M.; Tosi, F.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Q.; Tang, Y.; Mattoccia, S. GasMono: Geometry-Aided Self-Supervised Monocular Depth Estimation for Indoor Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 16163–16174. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Gu, S.; Duan, L.; Li, W. GeoDepth: From Point-to-Depth to Plane-to-Depth Modeling for Self-Supervised Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 11525–11535. [Google Scholar]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. NeRF. Commun. ACM 2020, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant neural graphics primitives with a multiresolution hash encoding. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, K.; Bian, J.W.; Prisacariu, V.A. Nope-nerf: Optimising neural radiance field with no pose prior. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 4160–4169. [Google Scholar]

- Ranftl, R.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Koltun, V. Vision Transformers for Dense Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12179–12188. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S.F.; Alhashim, I.; Wonka, P. AdaBins: Depth Estimation Using Adaptive Bins. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 4009–4018. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Gu, X.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, S.; Tan, P. Neural window fully-connected crfs for monocular depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 3916–3925. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. BinsFormer: Revisiting Adaptive Bins for Monocular Depth Estimation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.00987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. DepthFormer: Exploiting Long-Range Correlation and Local Information for Accurate Monocular Depth Estimation. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluation Metric | VisionNeRF | PixelNeRF | MonoDepth2 | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Usage (MB) | 1423 | 1026 | 501 | 234 |

| Speed (FPS) | 5.7 | 6.9 | 20.1 | 22.8 |

| Real-time Capability | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Occlusion Handling | × | × | × | ✓ |

| Energy Efficiency (EER) | 3.42 | 4.12 | 8.31 | 18.92 |

| Method | Memory | FPS | KITTI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs Rel ↓ | ↑ | |||

| VisionNeRF | 1423 MB | 5.7 | 0.137 | 0.839 |

| PixelNeRF | 1026 MB | 6.9 | 0.130 | 0.845 |

| Ours | 234 MB | 22.8 | 0.102 | 0.887 |

| Method | Memory | FPS | V2X-Sim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs Rel ↓ | ↑ | |||

| VisionNeRF | 1423 MB | 5.7 | 0.128 | 0.857 |

| PixelNeRF | 1026 MB | 6.9 | 0.122 | 0.863 |

| Ours | 234 MB | 22.8 | 0.095 | 0.905 |

| Method | Volume | FPS | KITTI | V2X-Sim | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs Rel ↓ | ↑ | Abs Rel ↓ | ↑ | |||

| EPC++ | × | 18.4 | 0.128 | 0.831 | 0.120 | 0.848 |

| MonoDepth2 | × | 20.1 | 0.106 | 0.874 | 0.100 | 0.892 |

| PackNet | × | 15.2 | 0.111 | 0.878 | 0.104 | 0.896 |

| DepthHint | × | 15.8 | 0.105 | 0.875 | 0.099 | 0.893 |

| FeatDepth | × | 14.5 | 0.099 | 0.889 | 0.093 | 0.907 |

| Ours | ✓ | 22.8 | 0.102 | 0.887 | 0.095 | 0.905 |

| Method | Backbone | Memory | FPS | V2X-Sim | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs Rel ↓ | RMSE↓ | ↑ | ||||

| DPT-Hybrid | ViT-Hybrid | 345 MB | 16.7 | 0.108 | 4.45 | 0.882 |

| Adabins | EfficientNet-B5 | 298 MB | 19.6 | 0.101 | 4.38 | 0.885 |

| NeWCRFs | Swin-Large | 412 MB | 13.7 | 0.093 | 4.28 | 0.898 |

| BinsFormer | Swin-Base | 387 MB | 14.8 | 0.095 | 4.31 | 0.896 |

| DepthFormer | Swin-Tiny | 321 MB | 18.1 | 0.103 | 4.48 | 0.878 |

| Ours | ResNet-50 + LightMLP | 234 MB | 22.8 | 0.095 | 4.30 | 0.905 |

| Spherical Network | Prob. Sampling | Reproj. Loss | Abs Rel ↓ | RMSE ↓ | ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| × | × | × | 0.185 | 5.12 | 0.824 |

| ✓ | × | × | 0.162 | 4.87 | 0.851 |

| × | ✓ | × | 0.171 | 4.95 | 0.838 |

| × | × | ✓ | 0.147 | 4.65 | 0.869 |

| ✓ | ✓ | × | 0.138 | 4.52 | 0.875 |

| ✓ | × | ✓ | 0.125 | 4.41 | 0.882 |

| × | ✓ | ✓ | 0.131 | 4.47 | 0.878 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.102 | 4.39 | 0.887 |

| Method | w/o Reproj. Loss | w/Reproj. Loss | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| MonoDepth2 | 0.115 | 0.106 | 7.8% |

| PackNet | 0.119 | 0.111 | 6.7% |

| VisionNeRF | 0.174 | 0.158 | 9.2% |

| Ours | 0.137 | 0.102 | 25.5% |

| Num. Gaussians | Points per Gaussian | Abs Rel ↓ | RMSE ↓ | ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 16 | 0.118 | 4.58 | 0.874 |

| 3 | 16 | 0.108 | 4.45 | 0.883 |

| 4 | 16 | 0.102 | 4.39 | 0.887 |

| 5 | 16 | 0.105 | 4.42 | 0.885 |

| 4 | 12 | 0.112 | 4.51 | 0.878 |

| 4 | 20 | 0.106 | 4.43 | 0.884 |

| Lightweight MLP | Enhanced Encoder | Color Sampling | Memory (MB) | Abs Rel ↓ | ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| × | × | × | 1423 | 0.137 | 0.839 |

| ✓ | × | × | 892 | 0.151 | 0.821 |

| × | ✓ | × | 1156 | 0.119 | 0.864 |

| ✓ | ✓ | × | 378 | 0.128 | 0.849 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 234 | 0.102 | 0.887 |

| Method | Memory (MB) | Power (W) | EER | CRP (kgCO2/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VisionNeRF | 1423 | 285 | 3.42 | 40.6 |

| PixelNeRF | 1026 | 245 | 4.12 | 35.8 |

| MonoDepth2 | 501 | 189 | 8.31 | 16.5 |

| FeatDepth | 487 | 182 | 9.05 | 14.4 |

| Ours | 234 | 156 | 18.92 | 12.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ping, Z.; Pan, J.; Shan, H.; Li, R.; Chi, M.; Cui, Z. Enhancing Sustainable Intelligent Transportation Systems Through Lightweight Monocular Depth Estimation Based on Volume Density. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411271

Tan X, Wang C, Zhang Z, Ping Z, Pan J, Shan H, Li R, Chi M, Cui Z. Enhancing Sustainable Intelligent Transportation Systems Through Lightweight Monocular Depth Estimation Based on Volume Density. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411271

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Xianfeng, Chengcheng Wang, Ziyu Zhang, Zhendong Ping, Jieying Pan, Hao Shan, Ruikai Li, Meng Chi, and Zhiyong Cui. 2025. "Enhancing Sustainable Intelligent Transportation Systems Through Lightweight Monocular Depth Estimation Based on Volume Density" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411271

APA StyleTan, X., Wang, C., Zhang, Z., Ping, Z., Pan, J., Shan, H., Li, R., Chi, M., & Cui, Z. (2025). Enhancing Sustainable Intelligent Transportation Systems Through Lightweight Monocular Depth Estimation Based on Volume Density. Sustainability, 17(24), 11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411271