1. Introduction

Climate change remains one of the most pressing challenges of the twenty-first century, with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions driving unprecedented shifts in global temperatures, ecosystems, and human livelihoods. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [

1,

2], the Earth’s average surface temperature increased by approximately 0.85 °C between 1880 and 2012, while recent assessments warn that anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions account for over 75% of total GHG emissions, particularly in developing economies. These findings highlight the urgent need to align economic growth strategies with global climate stabilization targets, as emphasized in international frameworks such as the Paris Agreement [

3] and the European Green Deal [

4].

Within this context, the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis has served as a central framework for examining the relationship between economic growth and environmental quality [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The EKC posits an inverted U-shaped relationship in which environmental degradation initially rises with income growth but subsequently declines as economies advance, driven by technological innovation, structural transformation, and more effective environmental governance. Although the EKC framework remains influential, empirical evidence is mixed and often context-dependent [

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, much of the existing literature overlooks sectoral heterogeneity—particularly the influence of agriculture, renewable energy adoption, and transport systems—as well as the mediating role of institutional and regulatory quality, which can substantially alter the trajectory of the growth–environment nexus [

15,

16,

17].

Agriculture remains both a key driver of economic growth and a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions in many economies [

11,

18]. At the same time, the energy and transport sectors constitute critical arenas for achieving large-scale decarbonization, given their substantial contribution to global CO

2 emissions [

19,

20]. The effectiveness of environmental regulation ultimately determines whether economic expansion entrenches carbon-intensive production or fosters a transition toward sustainable growth [

21,

22]. These interdependencies suggest that focusing solely on aggregate growth–emissions linkages risks obscuring the mechanisms through which structural change, technological innovation, and institutional quality shape carbon intensity across sectors [

23,

24].

The global urgency to mitigate climate change has intensified efforts to understand the structural determinants of carbon intensity (CI) across diverse economic contexts [

25,

26]. In the case of ex-socialist European Union (EU) countries, the transition from centrally planned to market-oriented economies initiated profound shifts in industrial, agricultural, and energy systems [

10,

27]. These transformations were accompanied by rapid liberalization, privatization, and integration into EU markets, fundamentally altering patterns of production and energy use [

28,

29]. However, this structural reorganization also generated distinct environmental challenges related to carbon emissions—particularly from the agriculture and transport sectors—which remain among the most carbon-intensive areas in post-socialist economies [

10,

18,

20]. Understanding these dynamics is essential for assessing the progress and sustainability of low-carbon transitions in the region.

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis has long served as a central framework for examining the complex relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation. While a substantial body of research has explored the EKC across sectors, relatively fewer studies have focused on agriculture—a sector that simultaneously drives economic development and contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

30]. Understanding how agricultural transformation influences emission patterns is therefore essential for achieving low-carbon and sustainable growth, particularly in economies undergoing structural transitions.

The determinants of agricultural carbon emissions have been extensively examined within the EKC framework, yet findings remain inconsistent across regions. Much of the empirical evidence originates from China, reflecting both the scale of its agricultural sector and the intensity of its structural transformation. Liu and Feng [

31] found that between 2005 and 2013, economic growth and income distribution increased agricultural energy-related emissions, while rural income structures mitigated them. Zhang et al. [

19] confirmed the EKC hypothesis, showing that energy consumption exacerbated emissions and that bidirectional causality existed between agricultural growth and emissions, with unidirectional causality from energy use to both emissions and growth. At the provincial level, Li et al. [

32] reported that R&D intensity and rural disposable income reduced emissions, whereas agricultural labor, value added, and land expansion heightened them. Song et al. [

33] further demonstrated that fertilizer use, energy intensity, and structural characteristics of agriculture were dominant emission drivers, while urbanization, public investment, and large-scale farming exerted mitigating effects. Overall, these studies suggest that while agricultural growth and energy use tend to increase emissions, institutional and technological factors can moderate their environmental impact.

Recent scholarship has increasingly emphasized the crucial role of technology and modern practices in low-carbon and sustainable development of agriculture. Li, et.al [

32] showed that digital technology innovation enhances low-carbon agricultural performance through efficiency and cleaner production. Lu, Chen, and Luo [

34] identified grain production agglomeration and environmental efficiency improvements as key drivers of green agricultural growth, while Luo, Huang, and Bai [

35] highlighted how low-carbon policies and farmers’ green preferences jointly facilitate sustainability transitions. Ji, Li, and Zhang [

36] examined structural and technological determinants of agricultural carbon emissions, and Geng et al. [

37] emphasized the role of productive services in promoting technological diffusion and sustainable input use. Cai et al. [

38] further linked climate change impacts to the broader dynamics of green agricultural development and resilience. Last but not least, Huang et al. [

39] further examined regional differences in agricultural carbon emissions in China and found significant spatial heterogeneity driven by variations in economic structure, technological efficiency, and agricultural practices, emphasizing the need for region-specific low-carbon strategies. Overall, these studies suggest that while agricultural growth and energy use tend to increase emissions, institutional and technological factors can moderate their environmental impact. Collectively, these studies underscore a growing consensus that technological innovation, institutional support, and environmental efficiency are essential for advancing low-carbon agriculture.

Studies across regions have examined the determinants of agricultural emissions, offering complementary insights. In Asia, Paul and Bhattacharya [

40] identified energy intensity, economic growth, and emission intensity as the main drivers of rising agricultural CO

2 emissions in India between 1980 and 1996. In South Korea, Oh et al. [

41] found that agricultural emissions from 1990 to 2005 were mainly influenced by energy intensity and output expansion, while Akram et al. [

42] showed that in Pakistan (1990–2016), economic activity and population growth were the major contributors, emphasizing the need for policy reforms, decentralized energy systems, and emissions trading to mitigate these effects. Collectively, these studies highlight the central role of energy intensity and economic growth in driving agricultural emissions across Asian economies, underscoring the importance of policy intervention to redirect these trends.

Evidence from European economies further emphasizes structural and technological dimensions. Diakoulaki et al. [

43] found that in Greece (1990–2002), rising energy intensity, economic expansion, and an unfavorable energy mix were the main sources of agricultural emissions. Similarly, Cansino et al. [

44], analyzing Spain between 1995 and 2009, concluded that higher energy consumption outweighed the benefits of technological progress and structural change, making it the dominant factor behind emissions. These findings suggest that energy-related pressures often overshadow efficiency and structural improvements in shaping agricultural emission patterns.

Research from other developing and emerging economies reveals further heterogeneity. In Nigeria, Maji et al. [

45] found that financial development and economic growth reduced agricultural emissions between 1971 and 2011, whereas population growth and foreign direct investment increased them. Ismael et al. [

46], focusing on Jordan, demonstrated agriculture’s dual role as both a contributor to and a victim of climate change, with agricultural production, land use, and value-added increasing emissions while income showed bidirectional causality with emissions. These mixed findings indicate that in developing contexts, the balance between growth and emission mitigation depends on demographic pressures, financial systems, and institutional conditions.

Cross-country analyses also offer broader evidence. Magazzino et al. [

47] examined 50 countries from 1990 to 2018 and found that forest density, population growth, agricultural practices, and economic development significantly influenced agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, though their magnitude and direction varied. This diversity underscores the need for panel-based approaches that capture cross-country heterogeneity in the agriculture–emissions relationship.

Overall, global evidence suggests that while energy intensity, fertilizer use, and structural change consistently drive agricultural emissions upward, factors such as income distribution, R&D investment, financial development, and institutional quality can mitigate these effects [

8,

9,

46,

47,

48]. Yet, the absence of consensus across regional studies highlights the need to revisit the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) framework through a more integrated and multidimensional lens that captures the complex interactions among economic, technological, and policy variables.

In the context of Central-eastern and South-eastern European countries, research examining the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) remains relatively limited, particularly regarding the role of institutions and agricultural transformation in shaping environmental outcomes. Early evidence by Solakoglu [

49] shows that stronger property rights improve environmental quality, while Tamazian and Rao [

50] find institutional quality to be a significant determinant of environmental performance in 24 transition economies. More recent analyses reinforce these findings: Nedić et al. [

51] report that institutional effectiveness and governance reforms significantly reduce pollution levels in Balkan transition states; Addai et al. [

52] show that countries with strong regulatory frameworks have achieved improved environmental quality by curbing unsustainable growth and limiting fossil-fuel consumption in EU transition economies; Additional evidence increasingly indicates that EU membership significantly strengthens climate mitigation efforts by promoting harmonized policies and improving governance quality. Accession encourages alignment with strict environmental directives, boosts institutional capacity, and accelerates low-carbon policy implementation. Comparative evidence from Triarchi et al. [

53] shows that Balkan EU members have achieved notably larger CO

2 reductions than non-members, driven by the EU environmental acquis and stronger regulatory oversight. Overall, the literature indicates that EU membership positively shapes the ambition and effectiveness of climate policies in transition economies.

Despite these advances, the existing literature remains narrow in terms of a sector. Most studies examine aggregate emissions and general governance indicators, without addressing how institutional mechanisms influence environmental outcomes through specific sectors such as agriculture, which remains a central economic activity—and a significant source of methane and nitrous oxide emissions—in many ex-socialist EU countries. Importantly, few studies have integrated agriculture-led growth, regulatory quality, renewable energy development, and sectoral restructuring into a unified EKC framework. Given the profound agricultural reforms, institutional restructuring, and EU-driven regulatory alignment experienced by post-socialist countries, there is a clear need for an expanded EKC approach that captures both the direct and indirect effects of governance and the critical role of agriculture in shaping carbon intensity trajectories.

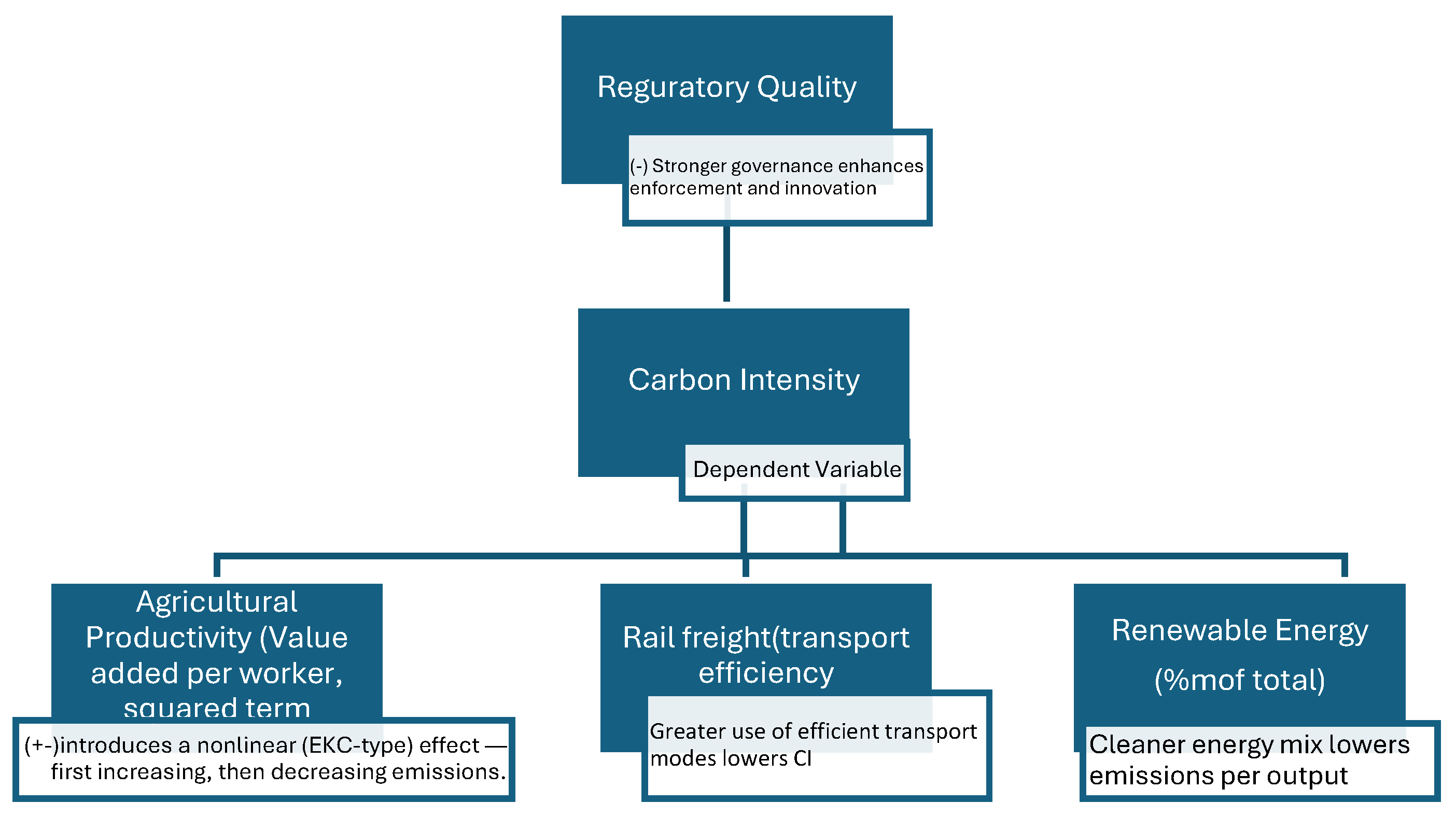

Addressing this gap, the present study extends the EKC framework by integrating agricultural value added, regulatory quality, and renewable energy into a unified analytical model to provide new empirical insights into the determinants of carbon intensity and sustainable growth in transition economies.

By integrating sectoral, regulatory, and energy-related determinants within a unified empirical framework, this study advances the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) literature in several important ways. First, it moves beyond conventional analyses centered predominantly on aggregate emissions by examining the heterogeneous dynamics of carbon intensity across key economic sectors. This sector-sensitive approach captures structural asymmetries that aggregate indicators obscure, thereby offering a more refined understanding of the technological, behavioral, and production-related constraints shaping decarbonization trajectories in post-socialist European economies. Second, the research underscores the critical moderating roles of governance quality and renewable energy deployment, demonstrating that institutional effectiveness, regulatory coherence, and the pace of low-carbon energy integration systematically condition the functional form, magnitude, and stability of the growth–environment relationship. In highlighting these interactions, the study elucidates how institutional capacity and energy-system transformation jointly influence the feasibility of attaining sustainable growth and achieving long-term emissions reductions.

Third, by situating these mechanisms within the broader context of transitional economies characterized by distinct historical legacies, evolving regulatory frameworks, and persistent structural rigidities, the study fills a significant gap in the existing literature. It provides empirical evidence that the environmental and developmental trajectories of post-socialist countries do not necessarily mirror those of advanced market economies, calling attention to context-specific drivers of environmental performance and to the differentiated policy interventions required to foster sustainability in transition settings. Furthermore, the study’s methodological approach—combining sectoral decomposition with interactive governance and energy variables—offers a replicable framework for future comparative research on carbon intensity dynamics across diverse institutional and economic systems [

54].

Collectively, these contributions deepen our understanding of the multidimensional determinants of carbon intensity and strengthen the theoretical and empirical foundations for analyzing EKC dynamics in structurally evolving economies. They also furnish policy-relevant insights for designing integrated, institutionally grounded, and energy-conscious strategies capable of supporting low-carbon development pathways in regions undergoing profound economic transformation [

55,

56,

57].

3. Results

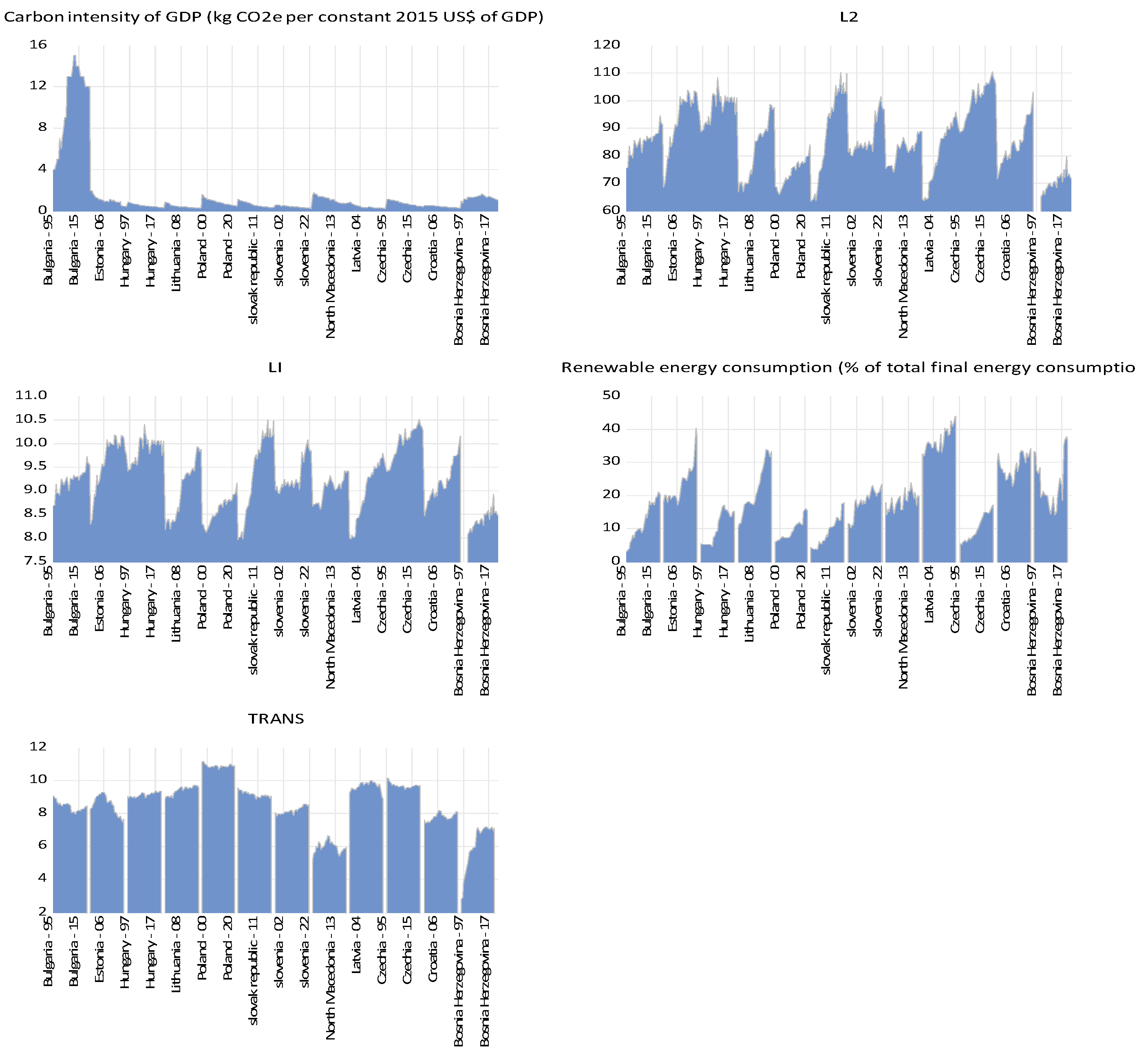

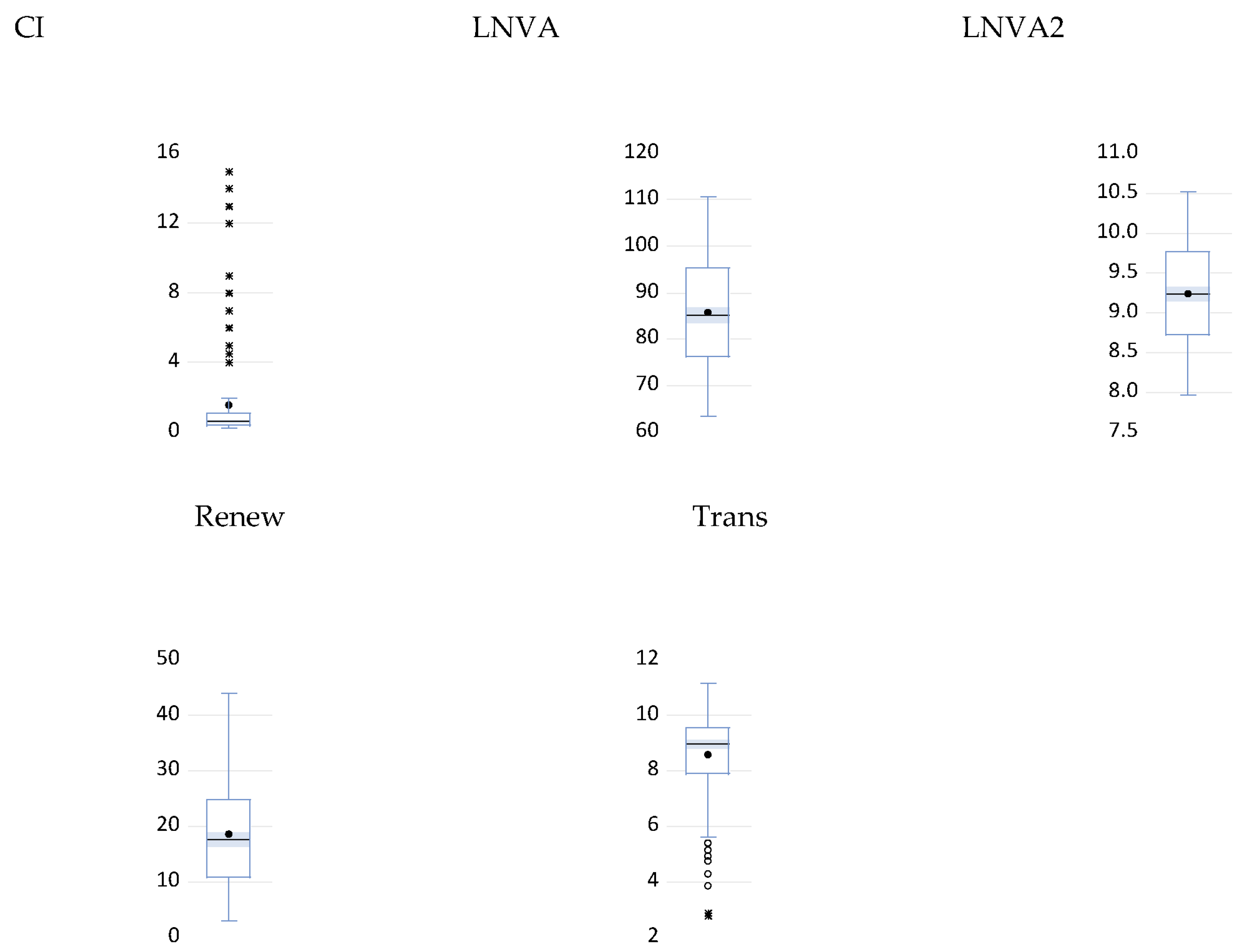

The first stage of our methodology section involved the employment of cross-section dependence tests, the results of which are provided in

Table 2. More specifically, the results of the Breusch–Pagan LM, Pesaran scaled LM, bias-corrected scaled LM, and Pesaran CD tests all yield

p-values of 0.000, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence at the 1% significance level for all variables (CI, lnVA, RENEWER, Trans, and regeq). This indicates that the residuals across cross-sectional units are correlated, confirming the presence of strong cross-sectional dependence (CSD). Such dependence suggests that common shocks or unobserved global factors simultaneously affect multiple units in the panel.

The simultaneous presence of cross-sectional dependence and slope heterogeneity reveals the inadequacy of first-generation panel unit root and cointegration tests, which rest on the restrictive assumptions of cross-sectional independence and parameter homogeneity [

81]. Consequently, the application of second-generation panel techniques becomes essential, as these methods explicitly accommodate both cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity, thereby yielding more consistent and efficient inferences [

70,

71].

Given the strong evidence of cross-sectional dependence established by the preliminary diagnostic tests, the empirical investigation proceeds with second-generation unit root tests. Specifically, the CIPS test [

69] and the PANIC test [

70] are employed, as both methodologies explicitly model cross-sectional dependence through common factor structures. These approaches provide more reliable insights into the integration properties of the variables under consideration. The corresponding empirical results are reported in

Table 3.

The second-generation unit root tests—the Bai and Ng PANIC test and the Pesaran CIPS test—both show that all variables behave as integrated processes of order one. At their level form, neither test provides convincing evidence of stationarity. The PANIC statistics for carbon intensity, agricultural value added, transport volume, renewable energy share, and regulatory quality are all statistically insignificant, indicating non-stationary behavior. The CIPS test leads to the same conclusion, as the level statistics generally fail to reject the presence of a unit root, with the only partial exception of regulatory quality, which shows weak evidence of stationarity.

When the variables are transformed into first differences, the results from both tests become clear and mutually reinforcing. The PANIC test identifies all differenced variables as statistically significant, while the CIPS test also decisively rejects non-stationarity across all series. Taken together, these outcomes confirm that carbon intensity, agricultural value added, transport activity, renewable energy use, and regulatory quality are non-stationary in their levels but become stationary once differenced, indicating that each series is integrated of the first order.

Overall, the panel can be characterized as predominantly first-differenced stationary, which is consistent with the properties of macro–panel data. This justifies the application of panel cointegration techniques to examine potential long-run equilibrium relationships among the variables. Accordingly, the subsequent analysis employs the Kao, Pedroni, and Fisher–Johansen panel cointegration tests to determine the existence of such long-run relationships [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77].

To be more specific, the model employed is expressed in the following mathematical form.

The results are synopsized in the

Table 4.

The Pedroni residual cointegration test indicates that the variables are cointegrated in the long run. While the Panel v- and rho-statistics fail to reject the null hypothesis, both the Panel PP and Panel ADF statistics are significant at the 1% level, providing robust evidence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between carbon intensity, agricultural value added, renewable energy, transport, and regulatory quality. This finding supports the application of long-run estimators such as FMOLS and DOLS in subsequent analysis.

Consistent with the Pedroni test outcomes, the Kao residual cointegration test also rejects the null hypothesis of no cointegration, confirming the existence of a stable and statistically significant long-run relationship among carbon intensity, agricultural value added, renewable energy, transport, and regulatory quality.

The Johansen Fisher Panel Test further strengthens this conclusion by revealing multiple cointegrating vectors, with highly significant statistics for the null of no cointegration and for at most one and two cointegrating equations. Taken together, all the panel cointegration tests employed consistently confirm the existence of a long-run equilibrium among the variables. Despite minor inconsistencies in individual Pedroni statistics, both the Kao and Johansen–Fisher results strongly reject the null of no cointegration. Overall, the evidence validates a stable long-run relationship, supporting the use of FMOLS, DOLS, and panel ARDL estimators in subsequent analysis. A synopsis of the cointegration results is presented in

Table 5.

Having validated the cointegration we estimate a model based on two different methodologies including FMOLS and DOLS, the results of which are provided in

Table 6 and

Table 7, respectively. We note that the regulatory quality variable was incorporated into both model specifications as a deterministic regressor. This inclusion allows us to account for the institutional environment’s indirect influence on agricultural income, as well as on its nonlinear component captured through the squared term. By explicitly introducing regulatory quality into the deterministic part of the model, we are able to distinguish the role of governance structures from the stochastic dynamics of the series and more accurately assess how institutional conditions shape the trajectory of agricultural development.

The panel FMOLS results show that income, transport efficiency, and renewable energy consumption exert significant long-run effects on carbon intensity (CI). The positive effect of income combined with the negative effect of its squared term confirms an inverted U-shaped EKC relationship, indicating that CI rises in early development stages but declines as economies advance and adopt cleaner technologies. This pattern is consistent with earlier evidence from transitional and emerging economies, where structural change, efficiency improvements, and technological upgrading drive long-run decarbonization [

11,

60].

Transport efficiency and renewable energy use both reduce CI in the long run, underscoring the importance of shifting toward cleaner freight systems and expanding low-carbon energy supply. These findings align with prior studies demonstrating the environmental advantages of rail transport [

79,

85,

86] and the decarbonization benefits of renewables [

59,

87].

For post-socialist economies, the EKC turning point appears delayed due to inherited energy-intensive structures, slower technological diffusion, and uneven regulatory enforcement. Earlier research similarly notes that institutional transitions, governance fragmentation, and infrastructure deficits hinder rapid convergence toward sustainability targets. This suggests that external policy anchors—such as EU environmental directives, CAP reforms, and global climate commitments—play a critical role in accelerating the decoupling of economic activity from emissions.

The panel DOLS estimation (

Table 7), for the sample countries, provides robust evidence on the long-run determinants of carbon intensity (CI). The model demonstrates strong explanatory power (R

2 = 0.86). The positive and significant coefficient of income (LnVA), combined with the negative and significant coefficient of its squared term (LnVA

2), confirms an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and carbon intensity, consistent with the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis. The estimated turning point, at approximately USD 2780 per capita, indicates that emission reductions begin at relatively moderate-income levels.

The transport efficiency (TRANS), measured as rail freight volume in million ton-kilometers, and renewable energy (RENEWENER) variables—display the expected negative signs but lack statistical significance, suggesting that their mitigation impacts materialize more gradually.

To ensure the validity and robustness of the long-run estimates obtained from the FMOLS and DOLS models, a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) diagnostic was performed to assess potential multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. The results, presented in the following

Table 8, confirm that the estimated coefficients are not adversely affected by multicollinearity, thereby supporting the reliability and internal consistency of the model specifications.

The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) results indicate that multicollinearity is generally not a concern among the explanatory variables, except for LnVA (agricultural value added) and LNVA2 (its squared term). Both exhibit very high VIF values (approximately 690–700), which is expected given their mechanical correlation—the squared term is a nonlinear transformation of the original variable. Since this relationship is intentionally modeled to capture the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) effect, it does not invalidate the estimation. All other explanatory variables, including renewable energy (RENWEENER), transport efficiency (TRANS), and regulatory quality (REGURAQUAL), display VIFs well below the conventional threshold of 10, confirming the absence of harmful multicollinearity and the stability of coefficient estimates. Overall, the diagnostic results support the reliability of the model’s parameter estimates and the robustness of its empirical specification.

In order to enrich and further validate our findings we employed PMG ARDL estimation methodology that provided the following results in

Table 9.

The estimation results confirm a nonlinear relationship between agricultural value added and carbon intensity in the long run, supporting the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis. The positive and statistically significant coefficient of LNVA and the negative and statistically significant coefficient of LNVA2 indicate that emissions initially rise with agricultural productivity growth but decline beyond a threshold as efficiency and technology improve. REGURAQUAL shows a positive and significant effect, suggesting that in post-socialist economies, early stages of regulatory reform may temporarily increase energy demand due to institutional expansion and compliance adjustments. In contrast, RENWEENER and TRANS display negative coefficients, implying that greater renewable energy penetration and higher transport efficiency contribute to reducing carbon intensity. Together, these findings emphasize the dual challenge of managing agricultural modernization and institutional reform while promoting clean energy and transport systems as key levers of long-term decarbonization.

The short-run dynamics, estimated through the PMG-ARDL methodology and reported in

Table 10, highlight the limited responsiveness of carbon intensity to temporary shocks in agriculture, energy, and transport. This inertia underscores the importance of long-term policy continuity in transition and post-socialist economies, where institutional consolidation, energy diversification, and gradual infrastructure modernization are necessary preconditions for effective and lasting decarbonization.

Table 10 presents the short-run dynamics derived from the error-correction specification. The coefficient of the error-correction term (COINTEQ01 = –0.0269) is negative, as theoretically expected, but statistically insignificant (

p = 0.586), suggesting that deviations from the long-run equilibrium are corrected only weakly within the short term. This indicates that adjustments in carbon intensity occur gradually and are primarily driven by long-run structural factors rather than short-term variations. Most first-differenced variables, including agricultural value added (LNVA), renewable energy (RENWEENER), transport efficiency (TRANS), and regulatory quality (REGURAQUAL), show statistically insignificant short-run effects, confirming the limited responsiveness of emissions to temporary shocks. While the lagged changes in renewable energy and transport exhibit the expected negative signs, their lack of significance implies that the decarbonization impact of these sectors unfolds over a longer horizon. Overall, the results are consistent with the FMOLS and DOLS estimations, emphasizing that sustainable reductions in carbon intensity depend on persistent institutional, technological, and agricultural adjustments rather than short-term fluctuations.

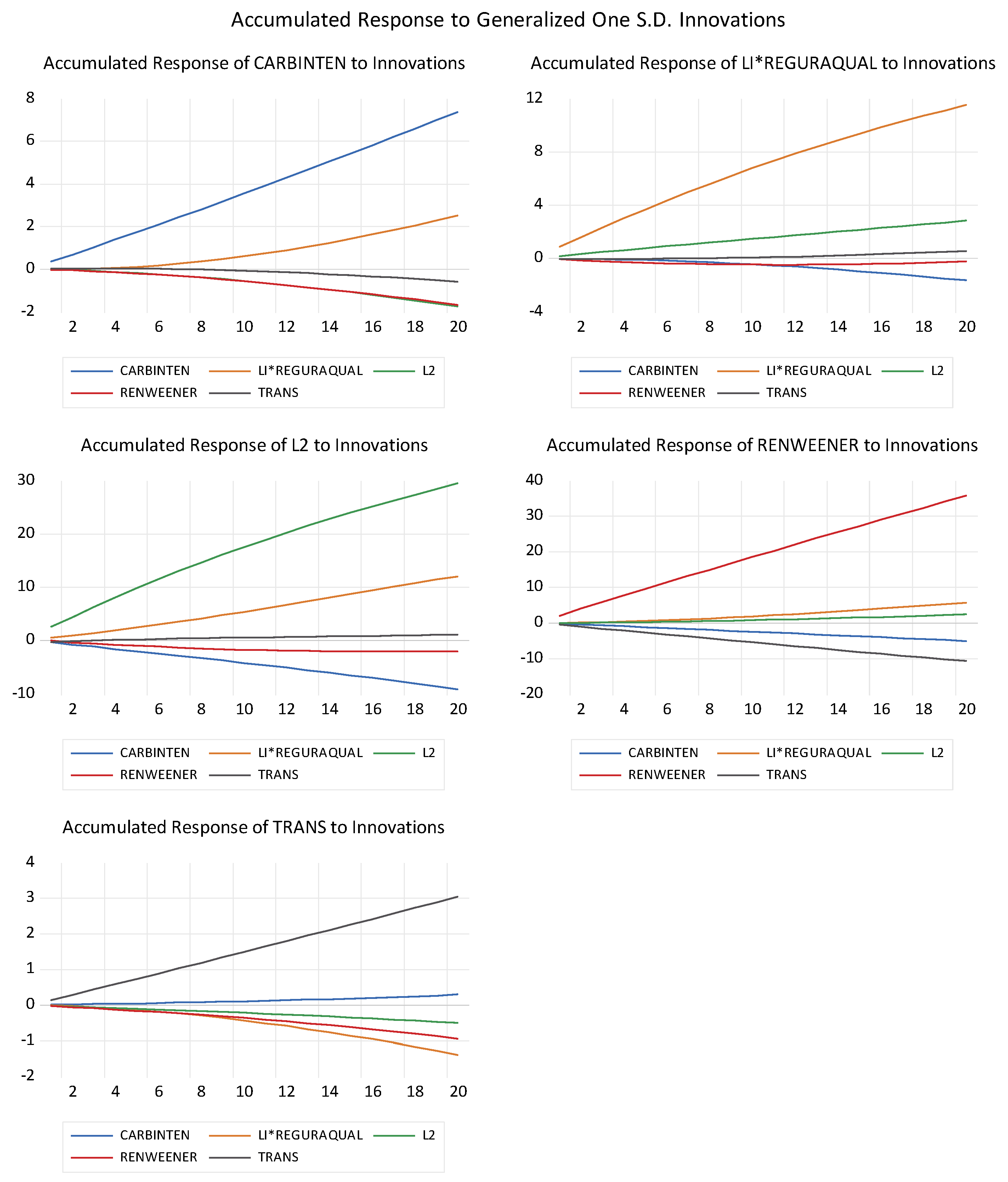

In the next stage of our analysis, we conducted a generalized impulse response analysis. Using Monte Carlo simulations, we obtained the following results as illustrated in

Figure 5.

The accumulated impulse response functions (IRFs) reveal how shocks to the key model variables affect carbon intensity (CI) and one another over time. The results highlight the dynamic interdependence among agricultural productivity (LNVA and LNVA2), renewable energy use (RENEWENER), rail freight transport (TRANS), and regulatory quality (REGURAQUAL), offering empirical insights into the mechanisms shaping long-run decarbonization.

A positive innovation in LNVA (value added by agriculture per worker) leads to a gradual increase in carbon intensity, indicating that productivity growth in agriculture initially raises emissions. This effect reflects the energy-intensive nature of early agricultural modernization—such as mechanization and fertilizer use—which typically increases fossil fuel consumption. However, the negative accumulated response of LNVA2 (the squared term of agricultural value added) suggests that after reaching a certain productivity threshold, further growth contributes to reducing carbon intensity. This pattern confirms the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) in the agricultural context: emissions rise with agricultural intensification in early stages but decline once technological efficiency, sustainable practices, and renewable energy integration become dominant [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

The accumulated responses to shocks in RENEWENER (the share of renewable energy in total final energy use) show a strong and persistent negative effect on CI, implying that increasing the renewable share plays a decisive role in mitigating emissions from both agricultural and industrial activities. Moreover, innovations in income and regulatory quality positively influence renewable energy adoption, suggesting that economic development and effective governance create enabling conditions for energy transition.

Shocks to TRANS (volume of goods transported by rail) display a moderate but long-run negative effect on carbon intensity, confirming that greater reliance on rail freight—an energy-efficient transport mode—reduces emissions over time. The initial short-run effects are weak, indicating that environmental gains from rail expansion materialize progressively as transport infrastructure improves and modal shifts from road to rail occur [

85].

The variance decomposition is another process incorporated in our analysis and the findings are provided in the next

Figure 6.

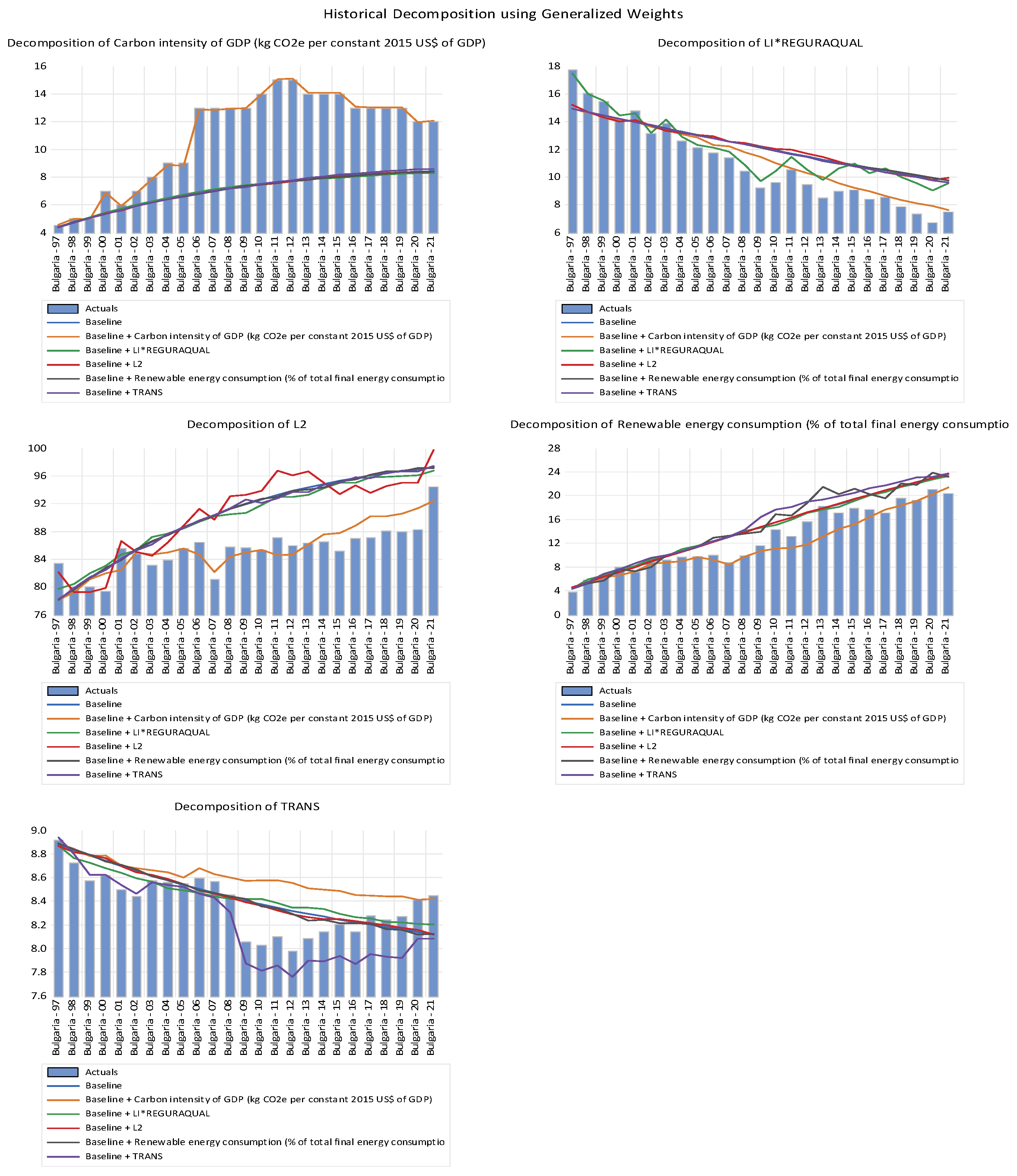

The historical decomposition results trace the relative contribution of each variable to the long-run evolution of carbon intensity of GDP (CO2 per constant 2015 USD of GDP). The patterns reveal how sectoral dynamics, energy structure, and institutional quality have influenced the trajectory of emissions efficiency over time across the 12 sampled countries.

Overall, carbon intensity (top-left chart) shows a gradual upward trend in the early years, followed by a clear decline beginning in the mid-2000s. This pattern reflects the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) mechanism previously established: emissions intensify during early stages of growth but decline once economies transition toward more energy-efficient production systems and adopt cleaner technologies.

The decomposition of LNVA (agricultural value added per worker) indicates that rising agricultural productivity initially contributed positively to carbon intensity, as reflected by the early parallel increase in both variables. This stage corresponds to intensive agricultural mechanization and fertilizer use, which are typically fossil fuel dependent. However, after the mid-2000s, the contribution of LI declined, suggesting that improvements in agricultural efficiency and the gradual adoption of sustainable practices helped to reduce emissions intensity.

In contrast, the LNVA2 component (squared term of agricultural value added) consistently offsets the upward pressure of LNVA, confirming that beyond a certain productivity level, agricultural modernization leads to environmental improvements. This nonlinear dynamic captures the decoupling of agricultural growth from emissions through technological advancement, precision farming, and renewable-powered irrigation systems.

The decomposition of RENEWENER (share of renewable energy in total final energy consumption) shows a steadily increasing contribution throughout the period. The rising trend of renewable energy use coincides with the downward trajectory of carbon intensity, reinforcing the strong negative relationship between renewable penetration and emissions per unit of GDP. Countries that expanded their renewable portfolios—particularly in electricity and rural bioenergy—experienced faster declines in carbon intensity.

The decomposition of TRANS (volume of goods transported by rail) reveals a negative contribution to carbon intensity over most of the sample period, though the effect becomes more pronounced after the early 2000s. This pattern suggests that the expansion and electrification of rail freight transport, which is more energy-efficient than road-based freight, have supported long-term emissions reductions. The small positive movements in recent years are likely to reflect increased freight demand outpacing efficiency gains in certain economies.

Finally, improvements in REGURAQUAL (regulatory quality) show a persistent negative contribution to carbon intensity, indicating that stronger institutions and environmental governance amplify the positive effects of renewable energy adoption, sustainable transport, and agricultural innovation. This highlights the pivotal role of policy enforcement and institutional capacity in sustaining decarbonization momentum.

The last step in our analysis is the Granger Causality Test aiming to detect the short run interlinkages among the variables studied, the results of which are provided in the next

Table 11.

The Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality analysis reveals a bidirectional causal relationship between carbon intensity and key explanatory variables, including agricultural value added, transport activity, and regulatory quality. This two-way causality suggests that not only does economic and sectoral activity influence environmental outcomes, but environmental pressures, in turn, feed back into productive and regulatory responses. The significant feedback between agricultural development and carbon intensity highlights the dual challenge of sustaining productivity while reducing emissions, indicating the need for climate-smart agricultural practices and targeted technological modernization.

The strong causal link between transport activity and carbon intensity further underscores the importance of advancing clean mobility strategies, such as investing in low-emission public transport systems, improving logistics efficiency, and supporting the transition to electric vehicle infrastructure. Meanwhile, the pronounced bidirectional relationship between regulatory quality and carbon intensity demonstrates that governance effectiveness is both a determinant and a consequence of environmental performance. Countries with stronger institutions are better equipped to enforce environmental standards and encourage sustainable behavior, while high carbon pressures may also motivate institutional strengthening and policy reform [

57,

60,

88,

89,

90].

Interestingly, renewable energy does not appear to Granger-cause reductions in carbon intensity, although the reverse relationship is significantly implying that rising emissions tend to stimulate the adoption of renewables rather than renewables yet driving large-scale decarbonization. This suggests that renewable energy deployment in post-socialist European economies remains largely reactive and policy-driven, rather than a structural driver of emissions reduction [

91,

92,

93].

From a policy perspective, these findings emphasize the need for an integrated approach that couples institutionally strengthened with proactive investment in clean energy and sustainable transport. Strengthening regulatory quality can amplify the long-term effectiveness of renewable policies, while fostering innovation and resilience in agriculture and logistics can help decouple economic growth from environmental degradation. In this context, environmental governance should move beyond compliance to actively incentivize technological adoption and promote cross-sectoral coordination, aligning national development strategies with the EU’s Green Deal and broader climate neutrality objectives [

94,

95,

96,

97].

Overall, these results emphasize the persistence of feedback loops linking carbon intensity with both historical emissions trajectories and sectoral dynamics. The EKC-related findings for agriculture, forestry, and fishing highlight the importance of policy measures that accelerate modernization in primary sectors to reach the EKC turning point sooner, especially in ex-socialist economies. At the same time, the asymmetry in renewable energy’s causality pattern underscores the need to shift from reactive to proactive renewable deployment, embedding it within structural reforms in energy intensity and transportation.

4. Discussion—Policy Implications

The robustness of the ensuing policy implications depends on a rigorous interpretation of the empirical evidence presented in this manuscript. The results of the Pedroni, Kao, and Johansen cointegration tests confirm the presence of stable long-run relationships among carbon intensity (CI), income, renewable energy, transport, and institutional quality, validating the application of FMOLS, DOLS, and PMG-ARDL estimators for long-run analysis. These estimators consistently indicate that CI is shaped by a combination of institutional, structural, and sectoral factors, with regulatory quality and transport activity emerging as the most robust determinants. This reinforces the view that governance effectiveness and freight efficiency are central to environmental outcomes, while economic growth alone is insufficient to achieve decarbonization.

The FMOLS and DOLS estimations provide strong confirmation of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis. In both models, income exhibits a positive effect on CI in early stages of development, while its squared term has a negative and significant impact, indicating that CI declines beyond a certain income threshold as economies modernize and adopt cleaner technologies. The estimated turning points differ across estimators: the FMOLS model indicates a threshold of approximately USD 11,400 per capita, whereas the DOLS model suggests a lower level of roughly USD 2780 per capita. This divergence may reflect differences in institutional capacity, technological diffusion, and policy implementation across countries, as well as the sensitivity of each estimator to heterogeneity and sample dynamics. Nevertheless, both estimations confirm the EKC relationship and support the existence of a transition path toward low-carbon development.

The results for the control variables are largely consistent with theoretical expectations. Renewable energy consumption (RENEWENER) and transport efficiency (TRANS) display negative effects in both models, indicating that greater reliance on renewables and improvements in transport systems contribute to reductions in carbon intensity over the long run. These effects are statistically stronger in the FMOLS model, but the consistency across both estimators reinforces the importance of energy structure transformation and cleaner freight logistics as central components of long-run decarbonization strategies.

The variance and historical decomposition analyses further reveal that reductions in CI stem from the combined influence of agricultural modernization, renewable energy uptake, rail-based transport development, and institutional strengthening. Initially, agricultural value added per worker increased emissions due to energy-intensive mechanization, but the squared term (LNVA2) exerted a persistent negative influence beyond a productivity threshold, confirming an EKC-type pattern within the agricultural sector. Renewable energy emerged as the strongest driver of decarbonization, while rail freight transport provided additional reductions, particularly after 2000 as economies invested in more efficient infrastructure. Improvements in regulatory quality amplified these effects by strengthening policy implementation, enhancing investment credibility, fostering innovation, and aligning sectoral transitions with environmental objectives.

The impulse response functions and causality results confirm that decarbonization depends not only on economic growth but also on coordinated policy action across agriculture, transport, energy, and governance. Asymmetries were observed in renewable energy causality, indicating that renewable deployment remains largely reactive to rising emissions rather than proactively reducing them—especially in post-socialist economies. This underscores the need for an integrated policy approach that embeds renewable energy and clean transport within structural reforms, supported by stronger institutions and long-term planning aligned with the EU Green Deal and broader climate neutrality objectives.

Based on the evidence, a successful decarbonization strategy should prioritize five complementary pillars:

The findings indicate that sustainable decarbonization requires a coordinated, multi-level policy strategy that integrates governance reform, sectoral modernization, and technological innovation. A comprehensive policy framework should follow five strategic pillars:

- ✓

Strengthen Regulatory Quality and Governance Capacity

Enhancing enforcement, monitoring, and anti-corruption mechanisms is essential for policy credibility and investor confidence. Transparent and predictable regulation, supported by performance-based monitoring, can reduce institutional inertia and improve compliance across sectors.

- ✓

Advance Sustainable and Climate-Smart Agriculture

To accelerate the EKC turning point, governments should promote precision farming, regenerative practices, and renewable-powered mechanization. Subsidies, green finance, and technical training—combined with digital tools for soil and water management—can facilitate a shift toward low-emission productivity growth.

- ✓

Transition from Reactive to Proactive Renewable Energy Deployment

Renewable integration should move beyond policy-driven responses to emissions pressure. Fiscal incentives, grid modernization, and decentralized energy schemes (e.g., solar irrigation, biogas, residue-based bioenergy) are critical for embedding renewables within rural and industrial systems.

- ✓

Modernize Transport Systems with an Emphasis on Rail

For post-socialist economies, rail electrification represents the most cost-effective decarbonization pathway in the near term. Logistics optimization and modal shifts away from road-based freight can reduce emissions substantially, while passenger electrification may be expanded gradually based on infrastructure readiness.

- ✓

Ensure Cross-Sectoral Coordination and Policy Coherence

Effective decarbonization requires the integration of energy, transport, agriculture, and environmental governance. Aligning institutional mandates and reducing policy fragmentation are particularly important in post-socialist contexts, where structural rigidities persist. Green innovation ecosystems—linking public governance reforms with private sector participation—can further support low-carbon transitions.

Overall, the empirical evidence provides strong support for the EKC hypothesis and indicates that sustained reductions in carbon intensity are primarily driven by structural transformation, technological innovation, and institutional enhancement, rather than by short-term fluctuations. Countries approaching or exceeding the EKC turning point—particularly former socialist economies—should strategically align their transition pathways with the European Green Deal [

95] and complementary policy instruments such as the Fit for 55 Package [

96], the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reforms [

97]), and the Just Transition Mechanism [

98]. These initiatives provide crucial external anchors for governance strengthening, sectoral modernization, and technological diffusion, especially in economies with inherited structural rigidities. By embedding clean energy adoption, sustainable transport development, and resilient agricultural practices within coherent governance frameworks, such countries can accelerate their shift toward low-emission systems. An integrated policy approach is therefore essential to ensure a durable decoupling of economic growth from environmental degradation and to consolidate a credible long-term trajectory toward low-carbon development [

99,

100,

101].